Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: NYLA

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

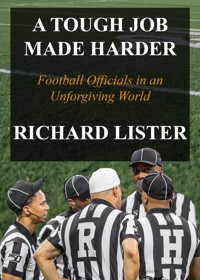

The only third-person account describing the lives and work of NFL game officials. There would be no NFL football without him. He is an accountant, educator, lawyer, sales executive, policeman, dentist, business owner, corporate executive, or fireman. He is an NFL game official. His life is a little like Clark Kent's; he lives a mainstream life Monday through Friday. On Sunday he puts on a uniform lending impressive power. He makes decisions affecting lives, careers, and fortunes. On his best day he is anonymous and unappreciated; on his worst, he is despised. He does a job from which fans, coaches, players, and even he himself demand perfection. He will never achieve it. Though having an essential part in a popular game, he prefers a low profile. His anonymity evokes curiosity about who he really is. The Third Team takes stories and reflections from interviews with 25 past and current National Football League officials, including some among football's greatest, to give the reader a look into a job that is far more exacting than even the most astute fan appreciates. The stories reveal the kind of person who reaches the pinnacle. Though competitive, wanting to be the best among peers, each man recognizes that his crew s performance has higher value than individual achievement. Becoming a team player will bond each crewmember into a powerful brotherhood. Their stories ranging from humorous to poignant give the reader insight into those working to keep NFL playing fields level for both teams. The perspectives are complemented by observations from former NFL coaches Tony Dungy, Steve Mariucci, Herman Edwards, and Jerry Glanville along with former player and current television analyst Matt Millen. The Third Team will appeal to the fan who is interested in the game's inner workings and who will appreciate stories from behind the scenes and inside the country's most popular spectator sport.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 683

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Third Team

NFL Officials - Their Lives, Their Stories

Richard Lister

This ebook is licensed to you for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be sold, shared, or given away.

The Third Team

Copyright © 2010 by Richard Lister

Ebook ISBN: 9781641971300

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this work may be used, reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

NYLA Publishing

121 W 27th St., Suite 1201, New York, NY 10001

http://www.nyliterary.com

Contents

Acknowledgments

Foreword

Preface

Part I

Help Wanted (part-time work, full-time hours)

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Refs

Part II

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Part III

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Notes

Also by Richard Lister

About the Author

For Vicky

Acknowledgments

There are many people to thank. Each person with whom I have spoken in writing this book has provided a memorable experience for me. I am grateful to everyone who took the time and who had the interest to contribute to this work. Hearing the officials’ stories and writing them has been a joy and a privilege. Each who contributed has a life story that inspires. My belief is that anyone who is interested in excellence and its pursuit will reach the same conclusion.

Writing this book could not have been possible without help from Bill Carollo, former NFL referee and current Coordinator of Football Officials for the Big Ten Conference. My good fortune to have sought his advice led to the opportunity to meet the other remarkable people described in these pages. He also shared ideas for the content, and he asked his daughter, Anna Burrall, to read the manuscript and lend editorial advice. For Bill’s interest in the book, his help, and for opening doors leading to his colleagues, I owe a debt of gratitude that I cannot come close to repaying.

I also thank coaches Tony Dungy, Steve Mariucci, Herman Edwards, and Jerry Glanville, as well as former player, former team executive, and current television analyst Matt Millen for taking the time to share their views on the men with whom, at times, they disagreed. Their reflections add light to the work done by those trying to maintain law and order on the field.

(Photo from Bill Nichols Collection)

I also enjoyed the chance to talk to and use the work done by Walt Smith from Frisco, Texas, and Bill Nichols of Modesto, California. Nichols (pictured in vest with NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell) and Smith are photographers who shoot NFL games. Both have developed a relationship over the years with the league’s officiating crews, with the result that they have taken thousands of pictures of officials. The chance to look at their work to consider which shots should be used represented a daunting challenge. But at the same time it allowed the opportunity to appreciate and enjoy the breadth and quality of the work they have done.

There are other notes of thanks. This endeavor took me on a search through the Internet to find an editor to help with the project. As was the case when I first undertook research for the book, I wasn’t quite sure where to start. The search for editorial help wasn’t too different. But I ended up with the very good fortune to find the right person for the job, Chris Stuart. Chris—who is not only a gifted writer, but a marvelous musician and composer as well—was wonderful in making suggestions that were appropriately direct but delivered with kind sensitivity. This book is so much the better for his help, guidance, and editorial contribution.

I also enjoyed the chance to again draw from my longtime friend, John Freeman. (As lab partners in 12th grade Physiology class, we dissected a cat.) John, formerly a sportswriter for the San Diego Union-Tribune, and currently in public relations, lent terrific advice that strengthened the book’s quality.

My sister-in-law, Jennifer Wiegand, also took an interest in the work. She has contributed thoughts that were astute as well as having proofread the manuscript, all adding polish to it.

Since this is my first effort at writing a book, the serendipity of having met consultant Patricia Benesh has been a great help as well. Her ideas and direction for writers have been most valuable toward putting the final touches on the book and getting it into print and distribution.

Finally, there is my endless thanks to my wife Vicky and our children Josh and Jessica. Every time I have read an author’s note of thanks to his or her family, most often I have glanced at the tributes without giving them much thought. Having now finished this book, I have a new understanding of those expressions of gratitude. My family’s encouragement has kept me going. They have made excellent suggestions that improved the book. And Vicky’s unending support for any adventure—or misadventure—that I choose to pursue is just a part of what makes her the wonderful wife she is.

Richard Lister, October 2010

Foreword

They are the most common refrains heard around stadiums, sports bars and family rooms from September through February every year—“Are you blind?” “You’ve got to be kidding me!” “Get a life!” NFL officiating, even though accurate more than 98% of the time, draws ire from fans, players, coaches and commentators with the regularity and certainty of a Bill Belichick mumble or a Rex Ryan profanity. Yet, away from the cursory reactions and behind the scenes, officiating professional football has proven to be one of the most demanding—physically, intellectually and emotionally—jobs that exist. The judgment and precision required are for only the most dedicated types; the tenacity and courage for only the most disciplined of souls. And all this for a part-time job!

In his book, The Third Team, Richard Lister artfully illuminates what is normally the background and skillfully debunks many of the myths that surround the responsibilities of those privileged to be NFL officials. More than that, he takes the reader to a world unknown by many outside the profession—the world officials live in the other six days a week. What many will find surprising is that this world is filled with studying and preparing. Like players and coaches, officials spend countless hours reviewing plays, studying rules and test themselves to get closer and closer to 100% accuracy. And, just like players and coaches, officials are constantly driven to succeed, but without any of the glory. Lister shares the agony of wrong calls and the analysis of high-definition instant replay in a way that makes you feel as though you’re making the call. And, get ready, because there’s no other profession where a two percent mistake rate is as scrutinized as this.

In addition to getting to understand the complex world of officiating in the NFL, the readers will get an inside look at some of the greatest officiating commissioners of professional football, not to mention some of the legendary coaches of all time. Hearing what it is like to work on the field with Coaches Shula, Parcells, Holmgren, Mariucci and more is the real bonus of this book. Never will you feel closer to the NFL than after reading these gridiron tales.

I love this book because it humanizes a profession that many have taken for granted. Lister shows the sacrifice, dedication and sense of humor that make NFL officials the greatest in sport. Despite the fact that players are bigger and faster, that the game is quicker and more intense, officials can be proud to employ their craft with ever-increasing accuracy. The age difference between player and official can be upward of forty years, and the official still finds himself in the right place making the right call. For what always has been and what always will be a thankless, mostly anonymous pursuit, Lister has shed light on a world that will undoubtedly educate and inspire his readers.

Bill Carollo

NFLRA-Executive Director and NFL Official, 1989-2008;

Coordinator of Football Officiating, Big Ten Conference

Preface

The telecast hadn’t been over thirty seconds when the phone rang. My sister, Kathy, a San Diego resident, was on the line. “What was that?” she demanded to know in a sharp tone. “Why did that guy do that?”

The Denver Broncos had just defeated the San Diego Chargers on September 14, 2008. Referee Ed Hochuli had made an error on a call during the game’s final minute. Kathy knew I had undertaken the research and had conducted interviews in this book’s first stages. She was looking for an explanation—or, more likely, for someone to whom she could express frustration.

Had Hochuli made the correct ruling San Diego would have won. My sister expressed feelings shared by Charger fans everywhere. I found myself reflexively reacting in a surprising way: I became defensive.

“It was an odd play,” I tried to explain. “It looked like it was a hard call.” She wasn’t having any of it. I pondered my reaction, somewhat surprised by it. I had already undergone a transformation in how I looked at the men in striped shirts. The empathy I sensed toward Hochuli—even though I have been a lifelong Charger fan—reflected a change in the way I watched football and how I regarded the game’s officials. How had I reached that place?

I considered how I arrived at it. I thought about the words spoken by referee Bill Carollo in one of our earliest conversations. He had told me that when he is asked at speaking engagements if he has a favorite NFL team, his reply is, “Yes. The one wearing black and white stripes.”

In July 2008, Mike Pereira took a seat at the small conference table in his corner office on Park Avenue in downtown New York. The NFL’s Vice-President of Officiating from 2001 through 2009 had a related question for me. “How did you land on this idea?” he asked. My thought was that a better question was: How did I wind up in Mike Pereira’s office?

The answers to these questions start with my love for the game. With time came a natural curiosity for its component parts. I enjoyed watching isolated players during the action. From time to time, I found myself focusing on an individual official, just to watch what he was doing during a play. It was a glimpse into a part of the game that was essential, but most often overlooked—at least until a major foul or controversial call surfaced.

My inquisitiveness grew about the officials’ Monday through Friday occupations. I knew that Hochuli, Howard Slavin and others practiced law as trial attorneys while working as NFL official on Sundays. I wondered how they could balance two challenging careers. There were other professionals in the ranks of league officials, along with men from an array of other lines of work. It seemed to me that it had to be a serious challenge to have the demands on an NFL official superimposed over a conventional occupation. Officials make critical decisions on NFL playing fields under the highest pressure on Sunday. Then they return to other stresses on Monday.

When television analysts would take the officials to task over a controversial decision, my thoughts turned to how it was that someone with another career found the obvious excitement that comes with taking part in a National Football League game to outweigh criticism from viewers and broadcasters, not to mention the abuse they take on the field at the stadium. I thought these must be uncommon people. They are essential to the game. But for the most part, they fly under the radar. Who are they? What motivates them?

As I wondered what the answers to these questions were, it occurred to me that a book about these guys would be interesting. I enjoyed reading Last Call, Jerry Markbreit’s autobiography written with Alan Steinberg, and Jim Tunney’s Impartial Judgment. Both authors, who happen to be two of the finest referees in the history of the game, recounted their lives and careers. But it seemed that a third-person view of NFL officials’ work, including the more anonymous six crewmembers other than the referee, would also offer some very good stories and insights into what drives a football official.

Unable to find a book that covered the subject from that perspective, the semi-absurd notion that perhaps I could do it began to overcome my judgment.

Late one Friday afternoon when nothing else in my work seemed pressing, I decided to take action. Knowing the idea could easily lose steam or that insurmountable barriers lurked ahead, I decided to take a step anyway.

I was reasonably certain that an inquiry to the league headquarters would get nowhere. The NFL rightfully protects its officials and access to them. But even in the face of these hurdles, there had to be a way to find out what motivates the NFL official and who he is in a human-interest light.

Google brought up the Web site for the National Association of Sports Officials. A slideshow with photos of board members scrolled past a picture of an NFL referee whom I recognized from the television. The brief bio said that he had served as the Executive Director for the National Football League Referees Association. He had the look of someone who might provide, if nothing else, some advice, should the book have any possibilities, or who might give enough frank disincentive to warrant forgetting about the whole idea. The Web site left enough clues that I could take an educated guess at the location of his Monday through Friday workplace. I posted a letter to Bill Carollo, figuring that chances were I would hear nothing in response.

I later related this story to Pereira, telling him that I took a 50-50 chance that I would hear from Carollo. “Well, you hit the right 50 percent,” said Pereira. Indeed I did.

In the middle of the following week I received an email from Carollo telling me how I might contact him to talk about the idea further. Carollo did far more than simply provide a roadmap. He opened doors that led to Mike Pereira’s office and arranged introductions to some of the most remarkable people I have ever met.

Carollo arranged for a meeting with the renowned former NFL referee Jerry Markbreit to talk about the possibilities for the book and its scope. That conversation made it plain that the work done by NFL officials is well beyond the realm of anything I could have imagined. And the person who does their job is someone well past ordinary. From that day, I would not see any football official the way I had before. And that understanding would evolve with each interview.

The game from the official’s perspective is much harder than it would seem to the outsider. As I spoke with NFL line judge Jeff Bergman and his brother, head linesman Jerry Bergman—sons of a most respected NFL official—I learned the intricacies that come with officiating on the line of scrimmage. Identifying the player on whom they would key—a focal point that can change with every offensive formation shift—became something to watch during a game. Even counting players between plays (something that is not as easy as you might think) demonstrated that those things that I had previously taken for granted in a game shouldn’t be overlooked.

After talking to Dean Look, who worked on the deep sideline, I found myself wondering how far the wide receivers would take their routes downfield, just as the side judge and field judge do before the snap.

I would try to determine when there would or would not be ten seconds taken from the clock when the offensive team committed a foul in the game’s final minute, or what the proper penalty enforcement was in odd multiple foul situations. The game simply became more and more interesting with each official I met, having learned from each.

But beyond that, with each interview my amazement increased at how difficult the job is. I had surmised that they spend time off the field to prepare for their three hours on it—but I had no idea how much. Their dedication to doing the job as well as it can be humanly done dominates their schedules.

With each meeting I found that the men who have done this work are rare people. They love what they do, and they embrace the challenge that comes with doing it on the largest sporting stage in the country. They see their charge as an important trust for those who are likely to level the harshest criticism toward their work.

They are also people who have excelled in their work Monday through Friday. They are integral to their communities. In short, they are models of achievement, constantly pursuing excellence in two spheres.

Having learned this, I will still have a favorite team on the field as I watch the games. But I will look at the officiating crewmembers with a deeper understanding for what motivates them, and that they are trying just as hard as the players to succeed at their jobs.

On one other note, the reader will find that I have consistently used the pronouns “he” and “him.” This is due mainly to the historical fact that all NFL officials have been men. I have followed this form to avoid what might have become unduly awkward sentences—or perhaps because I don’t have the skill to craft gender-neutral sentences without sounding clumsy. In any event, I feel compelled to offer this explanation.

With that said, it should also be noted that there are very capable women in football officiating ranks. Mike Pereira reports that a number of women working in advanced collegiate levels are very good football officials. It is not unreasonable to think that, in time, they will become part of the NFL officiating force.

One who has the skill to be asked to join the NFL as an official is resilient to criticism from others, but harder on himself than any fan, coach, or player. He rues his errors. He wants to perform a difficult job without flaw. He cares deeply about how his decisions impact others’ lives. But he loves his work, and he is as driven as those who play and coach the game.

I have developed an enduring respect and appreciation for the third team on the field—the one trying to make sure that neither side gets an unfair advantage. Should they make a mistake, I will understand that they are disappointed. If they are not publicly lauded for a good call, their satisfaction will not be lost on me.

While I had originally envisioned this book as a third-person look at NFL officials, it actually more reflects their world as they have seen it. So rather than giving an outsider’s broad view, the following pages really provide more from the officials’ own perspectives on their work and lives. But from hearing their stories and sharing them, I have achieved what I wanted to by undertaking this work; I have learned something about who they are.

When the reader has finished this book, perhaps he or she will understand how one might see football officials in a different way.

Part One

A Harder Job Than It Looks

“It’s a thankless job. I wouldn’t want to do it. Could they pay me to do what they did? No way.”

—Jerry Glanville, Former NFL Head Coach.

Help Wanted (part-time work, full-time hours)

Seeking middle-aged applicants who are already employed (including: accountants, attorneys, dentists, educators, firefighters, police officers, sales representatives, business owners, and executives) to supervise organized violence on Sundays, occasional weeknights and holidays. Must be able to take unlimited criticism with little to no praise. Possibility of injury.

Requirements: high level of intelligence, physical fitness, and extraordinary mental focus while absorbing crude verbal abuse. Some positions require the ability to keep up with men who can cover forty yards in 4.3 seconds. Requires knowledge of highly complex rules to be applied instantly and instinctively in front of huge audiences. Involves making split-second decisions that affect lives and fortunes.

The successful candidate should be able to devote in excess of forty hours per week with the expectation that the applicant already has a full-time job. Ten years of college-game or other high-level experience required.

If interested, apply to the National Football League, Attention: Department of Officiating.

Chapter One

Pursuing Perfection

He’d better not blink. Literally.

Closing his eyes, even for only a millisecond, risks missing the quarterback’s head thrusting downward. The abrupt movement before the snap is a false start—a foul. If he blinks, he might not see it. It can be that fast. Never mind that it’s a foul that doesn’t happen often. Stop concentrating for just an instant and that’s when it’s sure to slip past.

An old timer once told Jerry Markbreit that the best way to avoid the problem was simply not to blink. So, over his 22 years as an NFL referee, Markbreit willed himself not to blink.

Before the play, he would position himself, take a deep breath, put his hands on his thighs, and widen his eyes as fully as he could. He concentrated on keeping his eyes wide open. He wouldn’t allow his eyelids to move, even for an instant, from the time the quarterback set his offense until the snap.

If he blinks, he can miss a foul. And for a National Football League official, missing a foul is distressing. It is like a singer who misses a note. But for the official, it can happen more easily. And the criticism comes much quicker.

After each game, the NFL official asks himself: How many did I miss? He starts his career with a perfect record, but perfection can’t get better. From that moment he works to stay as close as he can to the high point. But his record will not be perfect.

He is judged by his mistakes. The NFL Officiating Department grades every play for each official. He cannot gain ground; he can only lose it. A running back can make up for a yardage loss with a long run. But imagine a variant of golf where birdies or eagles mean nothing and only bogeys or worse count. After a slip, there would be no way to return to par. The professional football official has no means by which to make up losses. His performance is measured by how close he stays to perfection.

Perfection’s expectation comes from different interests. The fan demands perfection—though it may not be enough if the result hurts the team. For the player and coach, it is an emotional entreaty to keep the opponent from getting an unfair advantage—though they won’t complain if they themselves happen to get one. For the NFL official, it is the standard against which he measures himself.

The athlete who makes it to the National Football League is too fast, too strong, and sometimes too guileful to be caught every time he commits a foul. The ball’s snap launches choreographed chaos. Twenty-two men work at cross purposes, engaging in individual fights over a 19,188 square foot playing field. Even for seven pairs of eyes belonging to those who are the best in the world at what they do, seeing everything—in every play, in every game, every year—is impossible. With a lapse in concentration, the problems multiply. Lost focus, even for one second, is a step removed from perfection’s standard.

It takes something as fleeting as the back judge, positioned behind the safeties, sneaking a quick glance backward in search of the goal line to miss the defensive back’s quick, illegal grab onto the receiver’s jersey.

If the side judge or the field judge, working downfield on the sidelines, is distracted by a screaming coach, he might not see the receiver as he pushes off the defender to get open.

Should the umpire quickly avert his scan from the players he is supposed to watch, he can miss the guard who adroitly grabs and twists the defensive tackle’s jersey, making just enough room for the ball carrier to slip through.

The head linesman or the line judge, flanking the line of scrimmage, might take an eye off the neutral zone, too concerned about finding his assigned key man as the offense shifts. When he does, he can miss seeing whether the offense or defense initiated the train wreck caused when someone violates the neutral zone.

Those who officiate in the NFL are well trained not to blink. They are the very best at what they do. The league employs only 120 officials (in contrast to the 1,693 players who man the active rosters on NFL teams). Those offered a job by the league do not slip far from the ideal. They make the correct judgment 97.5% of the time. But it’s the other 2.5% that everyone remembers—their mistakes bring attention. The plays judged well are mostly met with indifference. Many people don’t understand the job’s essence or its challenges. And many just don’t care.

Hall of Fame baseball umpire Nestor Chylak once observed, “They expect an umpire to be perfect on Opening Day and to improve as the season goes on.” The axiom is no different for any professional sports official. But the perspective on perfection varies.

Fans fixate on the 2.5%. They expect the official to work without error—but even that expectation comes with a condition. Flawless work is great if the fan likes the result. But a fan can criticize even a correct call if it hurts his or her team. Walt Coleman was right when he reversed his on-field ruling that the New England Patriots’ Tom Brady fumbled while tucking the ball during the 2001-02 AFC Divisional Championship game with the Oakland Raiders. It didn’t matter. Raider fans still disdain him.

Coaches and players focus on the 2.5%. Officials’ judgments can mean the difference in the final score. Victory and defeat are the beginning and the end for the professional athlete and coach. Wins and losses are dollars and cents. If an official’s error jeopardizes someone’s livelihood, he is going to hear about it—most often in an offensive way.

The NFL official knows how important his job performance is to those whom his decisions affect. His responsibility to ensure that the game is played fairly weighs on him. When a mistaken call costs a team, the official is as upset as the coach and players. Unwittingly affording one side an unfair advantage is a painful slip from perfection.

The game played in the NFL allows a very thin margin for officiating errors. Many outside the game don’t realize that the professional game’s speed is well beyond that played in college. Though having worked at least ten seasons with experience in high-level college games, a newly-hired NFL official must adapt to the professional players’ talent and quickness. The game’s faster speed at every position will amaze the rookie official.

A complex rulebook, with confusing regulations and exceptions to their application, confronts the NFL official. Many rules might not affect a play over many seasons. But the demand that any one be instantly called from memory, if needed, makes their study and memorization a nonstop job.

The time commitment requiring anywhere from forty to sixty hours a week for a job that is called part-time is a huge demand on one who already has a full-time occupation. There are coaches, sportswriters, and fans who believe the 2.5% slip from perfection would shrink if the league hired full-time officials.

Each time the official comes into an NFL stadium he knows that he is going to be berated by players and coaches in vile language. If he makes the correct decision on an extraordinarily difficult play, it matters little outside the fraternity. His best work is not acclaimed in public.

But in an instant, a high profile mistake can mar a career that took years to build. It will be talked about through one or more sports news cycles. It is not the way an official wants to become known, but it’s usually the only way.

The game demands law, order, and decisiveness. The one who gets this job isn’t worried about popularity. If that’s the goal, officiating is the wrong place to look for it. Seeking anyone’s favor is contrary to the work’s essence.

All of which leads to the question: Why would anyone want this job? The obvious answer is the chance it provides to work in the country’s most popular spectator sport at its highest level. But this scarcely explains what propels those who make it to the top.

An NFL field official is among the highest achievers: successful in his work Monday through Friday, among the best in the world at officiating football, and competitive—wanting to be the best at what he does. Like the fan, the coach, and player, he too is vexed by the 2.5%.

Every official wants to be as close to 100% correct as possible during the season and preferably the closest to it at his position. The prize for the best will be an assignment to a conference championship game or the Super Bowl. Work in the Super Bowl brings the official a ring as impressive as those awarded to the winning players. But ultimately there is something more important than individual achievement.

Perhaps more than any other game, a star on the football field needs help. It takes teammates to elevate an individual’s performance. This is just as true for the third team on the field—the officiating crew.

While an official wants to be the best, he understands that without his team, there will be no individual success. The crew comes first. Whether it’s coming in to help with a play that another might not have clearly seen, correcting a penalty’s enforcement, or clarifying a rule’s application, his first thought has to be for the team.

The crew’s solidarity evolves from an us-against-the-world outlook. The high-pressure work, mutual respect, and reliance on each other forge a rare unity and powerful loyalty among its members.

The league has some 2,200 applications from officials who would like to work in the NFL. Maybe six a year from the list will be selected. There has to be something very strong to pull someone toward a job that demands so much—a job that demands yet defies perfection.

Chapter Two

The Immaculate Reception—A Difficult Call

“I think the defense hit it.”

“Are you sure?”

“No.”

—Discussion Among Officials, 1972 AFC Divisional Championship.

Seeing all that’s going on during a typical play is hard enough. When the improbable intrudes—and it does from time-to-time—there may be no definitive answer to what happened. The play that has been called the greatest in NFL history came from the unexpected—complicating, even to this day, an understanding of exactly who did what. Sometimes you just can’t see everything.

The offensive line could no longer protect its quarterback. Horace Jones and Tony Cline had dismantled the pocket. The pass rushers, defensive linemen for the Oakland Raiders, tossed aside their blockers like flour sacks and were now intent on capturing their prey. Pittsburgh quarterback Terry Bradshaw could only run backward to escape.

The prolonged chase complicated things downfield. Backs and receivers ad libbed as the original plan crumbled. Things started to get more difficult for the downfield officials. The more than ten seconds consumed by the critical action made it longer than a typical play. The zones got a lot busier. There was more than the usual chaos. But it wasn’t near the chaos that would unfold in the next thirty seconds.

To that point, the game had been short on scoring, but it had all of the physical punishment that the Raiders and Steelers typically exchanged whenever they met. Jones and Cline wanted to end the game on a physical note. As Cline closed in, it looked as if he would catch Bradshaw. But the quarterback ducked to avoid him and kept retreating. Jones and Cline continued their pursuit. As Bradshaw backed up, so did referee Fred Swearingen.

Carrying out his assignment to keep his eye on the quarterback, Swearingen stayed behind the play. He watched as Bradshaw tried to find a spot to set his feet and unload the ball. Bradshaw didn’t have the luxury of throwing it away, living to play another down. When the play started, less than 20 seconds remained in the game. The Steelers trailed 7-6. It was fourth down. The 1972 AFC Divisional Title Game was at stake. Something good had to happen for the Steelers or their season would end. Cline and Jones persisted in trying to end it by putting Bradshaw on his back. The Steelers quarterback continued his retreat. As he did, Swearingen kept backing up. The referee didn’t know he was about to become a part of one of football’s greatest moments. And he didn’t know what controversy lay ahead.

Jones made one last grab. He missed by inches, grasping at Bradshaw with his right hand at the Steelers 29 yard line. The quarterback had no more options. An instant before the Oakland tandem knocked him onto his back, Bradshaw heaved the ball with strength and velocity few quarterbacks could match. The remaining Pittsburgh hope waited for the pass at the Oakland 35 yard line.

Bradshaw aimed the ball at running back John “Frenchy” Fuqua. But his intended receiver wasn’t alone. Oakland safety Jack Tatum lurked at the Raider 33 yard line. Tatum, feared and respected as a punishing defender, wanted to ensure that Fuqua wouldn’t catch the ball. Tatum drove his shoulder into Fuqua’s upper back precisely when the ball arrived.

The impact had its desired result. Fuqua didn’t catch the pass. Tatum’s energy redirected the ball backward and upfield. Tatum kept Fuqua from catching the ball all right. But there was an unintended consequence.

Joe Paterno drilled into his players at Penn State that if they always follow the ball, good things would happen. Paterno taught Franco Harris well. The Steelers’ rookie running back had run a route from the backfield. As Bradshaw scrambled for his team’s life, Harris slipped downfield toward Fuqua’s position.

The ball, now redirected backward, floated close to Three Rivers Stadium’s artificial turf. In full stride, Harris reached down and grabbed it. The crowd’s momentary dismay at Fuqua’s inability to hold the ball gave way to the realization that a miracle was unfolding. Harris carried the ball 40 yards into the Oakland end zone. The play, of course, became known as The Immaculate Reception.

Unlike the stadium crowd and television viewers, Swearingen did not witness the collision or the catch. His station in the backfield prevented him from seeing what had happened. At play’s end, he saw field judge Adrian Burk signal a touchdown.

Swearingen, now in his late eighties, has a ribald sense of humor, a head covered by white hair, and a knack for telling funny stories. Though once a splendid golfer, he has given up the game, now favoring crossword puzzles. But he recalls the famous Steelers-Raiders game like it might have happened last season. Even after 38 years, he speaks about the play in a tone reflecting unending exasperation. His voice rises in pitch and intensity as he describes the melee that erupted.

“The place just exploded. It really did. Both teams and the fans broke out of stands onto the field. I didn’t know what happened,” recalls Swearingen, muttering an expletive that underscores his enduring amazement. “The officials in the crew were lost in the thousands of people on the field. The teams were screaming at me, ‘What are you gonna do?’ I said, ‘About what?’ I didn’t even know what the question was.”

One invading the field was an exuberant 19-year-old Steeler fan. Having first thought that hope was lost when the ball bounced away from Fuqua, he turned away, disconsolate. Harris’s run, urged onward by the crowd’s resurgent roar, reignited the young man’s spirit. After the touchdown, he and his friend jumped the fence and joined the 5,000 fans on the field.

Given his love for the game and his father’s profession, the teenager had entertained the notion that he might one day work on NFL playing fields. But it’s doubtful that his father embraced his son’s exuberance. Nor, in later years, would the youthful fan be inclined to welcome a throng of fans onto an NFL playing field during a game. The teenager—Jeff Bergman, the son of NFL head linesman Jerry Bergman—would go on to become an NFL line judge.

About ten minutes after the mob overtook the field, Swearingen finally was able to collect his crew. Only then could he determine the issue. The Raiders maintained that the ball made contact only with Fuqua and Harris, and that it did not touch Tatum. The rules in 1972 made it an illegal pass if the ball was deflected by an offensive player to his teammate without having been touched by a defender. If the ball didn’t hit Tatum, the illegal touching would nullify Harris’s score. The Raiders added the additional protest that as Harris rescued the ball it was touching the turf.

Swearingen polled the officiating crew. He asked each member, “What did you see?” One by one, each reported. The head linesman said he did not see the play since he was watching players away from the collision. The line judge didn’t see the play either. The back judge said he was watching receivers and defenders in another area. Swearingen then came to veteran umpire Pat Harder.

He asked Harder what he had seen. “I think the defense hit it,” said Harder.

Swearingen questioned field judge Adrian Burk last. He, too, thought the ball had hit Tatum. Swearingen asked Harder and Burk the next question in slow, measured meter.

“Are you sure?”

“No,” each answered.

“Oh, well hell’s fire,” says Swearingen, explaining the thought that crossed his mind. “They’re not sure, and I don’t know. I didn’t see what happened. And I’m the one who had to make the decision.”

That’s a problem. Officials are expected to see everything. And they’re expected to make the right judgment every time. A classic moment in sporting history turned on an officiating decision grounded in uncertainty. That’s not the way anyone wants it. But sometimes that’s how it is.

The game is so fast and, at times, so unpredictable that the action taunts the human eye’s capability. Its athletes have rare abilities. Consider the talent possessed by those combining to make the play. Bradshaw and Harris are in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Tatum was an All-Pro safety.

Next, add the unexpected. Art McNally, the NFL Supervisor of Officials from 1968 through 1990, says that he can’t recall an instance where two offensive players touched a pass in succession during the entire 1972 season. It’s possible that it hadn’t happened in several previous seasons. It was a rare occurrence.

Without the combination of the players and the circumstances, there would have been no officiating problem. But then, the NFL would be without the play that NFL Films has called the greatest in league history. Fuqua and Tatum’s convergence at the ball’s arrival and the ensuing hustle by Harris to salvage the catch happened in a way that would test the keenest eye.

Even if an official fully expected the play’s sequence, it would have been a difficult judgment to make. The crew members, tracking the men running down and across the field, didn’t have the luxury to fix their gaze on Fuqua and Tatum in the expectation that they would have to determine who was going to touch the ball first.

So Swearingen had to settle, then and there, facts that remain in dispute today. Over the years, even physicists have entered the debate, giving opinions whether it was Tatum or Fuqua who propelled the ball backward. But Swearingen couldn’t rely on science. Nor could he consult television’s video replay, though urban legend says otherwise. He had to make the decision based on the equivocal answers given by Harder and Burk.

Then, just when it seemed that circumstances couldn’t get worse, they did. As Swearingen absorbed what his crew had reported, a Steeler employee carrying a walkie-talkie approached the crew.

“Art’s calling for Fred,” yelled, Jimmy Boston, a Pittsburgh man the home team and the league used to relay injury and penalty information from the field to the press box. Art, to whom Boston referred, was Art McNally.

McNally had been watching the game from the press box. The time passing during the crew’s huddle caused McNally increasing discomfort. Five seconds remained on the game clock. The game had to be finished.

As the officials prolonged their conference, McNally began to wonder what the problem was. He, like Swearingen, saw Burk—a former quarterback for the Philadelphia Eagles—give the touchdown signal.

“What’s the matter?” McNally says he recalls thinking. He thought perhaps his men had a problem with the rule. To McNally, the delay felt like “an eternity.” He decided that he needed to act. He found Steeler Public Relations Director, Gerald Gordon. McNally asked if Gordon could give a walkie-talkie to Boston. Gordon accommodated the supervisor’s request.

Having established communication with the field, McNally asked Boston: “Look, we’ve got to get some information. If I ask you to get Fred Wyant, will you find him and find out what’s the problem?” Wyant had been appointed the alternate referee for the game.

McNally recalls, “The problem was that our second Fred, who was an alternate official, who had a jacket on, was standing at the back of the end zone with all of these people—thousands of people—on the field.” The common first name that Wyant shared with Swearingen lent to the confusion and the problems that followed.

Amid the excitement, Boston didn’t fully understand what McNally wanted. First, McNally only wanted to know whether Boston could locate Wyant if McNally wanted to speak with the alternate referee. Boston thought that McNally wanted to speak immediately with Fred. Only he didn’t find Fred Wyant. He found Fred Swearingen.

Swearingen wondered: What could McNally want from me? The referee asked Boston who had the other walkie-talkie. Boston replied that it transmitted to the press box. “I will not talk to anyone in the press box,” said Swearingen emphatically. Boston pointed to one of the dugouts used during the baseball season. He said the telephone there would go directly to McNally.

By this time, McNally had resumed his seat. Not thirty seconds later, he saw Swearingen walk off the field to the baseball dugout.

“All of a sudden, the referee is leaving the field. Fred Swearingen goes to the dugout,” says McNally. He thought: What is this? The supervisor grew more perplexed and concerned. He continued to wonder if the illegal touching rule was a problem for the crew since it was an unusual play. Then, Gordon said to McNally, “You’ve got a phone call.”

“I told the guy with the walkie-talkie to get Fred Wyant, if I need him; but not now,” says McNally. “He misinterpreted. He went to the referee.” Summoning Swearingen from the field was the last thing McNally wanted to do.

Swearingen picked up the dugout phone. McNally answered. “Art, if you know something that I don’t know, tell me now,” Swearingen recalls saying to the boss. Swearingen recalls that McNally told him everything was fine, but that there were five seconds left in the game. “He told me, ‘You’ve got five seconds to play. Get ‘em off the field.’” Swearingen hung up and returned to the field.

“I’ll never forget what he said,” McNally recalls. “He said, ‘Two of my men ruled that the ball was touched by the opposing players.’ That was what he said. As soon as he said that, I said, ‘Okay, you’re fine. Go ahead and go.’”

McNally stresses that Swearingen did not ask what McNally had seen. “He never asked the question. He made the statement that the ball was touched by two opposing players. I didn’t say to him, ‘That’s a touchdown.’” The supervisor ended the conversation with the directive that Swearingen get back to the field.

At that point, Swearingen decided to reaffirm the decision that Burk had made. He confirmed it by raising his arms overhead, signaling the touchdown. The signal’s timing would add more fuel to speculation over what McNally and Swearingen had discussed.

“I gave the phone back to Gerald Gordon,” says McNally. “What I didn’t know was that when Swearingen left the dugout, he turned around and signaled touchdown. So now we were going to finish the game,” McNally continues. “In the meantime, NBC sent a runner down, and they wanted to find out what happened.”

The network deduced that Swearingen was on the phone with his supervisor. “They wanted me to go on TV and tell them what happened,” says McNally. He had been prepared to explain in detail what had transpired. At some point, the television director changed his mind.

“When I got downstairs, there wasn’t anybody at the officials’ locker room. They were all down at the Steelers locker room. Normally, what I would do is say, ‘Okay, let’s get the crew together and talk over what happened.’ But in Pittsburgh, members of the chain crew dress in the same room. By the time I got down there, they were starting to get changed and I didn’t want to throw them out of the room. We don’t have any problems. Nobody’s bothering us. Nobody is screaming for information. Let them get changed. So I never was asked. I never said anything. We got in the cars and we took off,” recalls McNally.

On the way to the airport, McNally finally had the chance to inquire into what caused the delay. He learned that it wasn’t the rule that slowed the officials.

“One of the crew said, ‘We had the touchdown—Adrian ruled touchdown.’ As they talked, everything seemed to be clear, but it wasn’t like a hundred percent,” says McNally. The Raiders’ protest caused the crew to consider the question of who redirected the pass.

The atypical events resulted in two barrels of buckshot being discharged at Swearingen. The first came from not having a conclusive answer to whether the ball hit Tatum or Fuqua. The second came from the notion that Swearingen resorted to McNally and the video replay to make his decision. While Swearingen and McNally say it never happened, some don’t believe it.

Based on officiating fundamentals, the crew made a sound decision, even if not locked in certainty. Equivocation over what an official witnessed makes for a tough day at work. But there is no escape from its occasional incidence. The NFL athletes’ abilities and the game’s nature assure that the answer won’t always be obvious.

Tatum insisted the ball never touched him. Fuqua has offered to divulge his version for a rather steep price. But Swearingen was the one who had to decide what happened, making a decision that would endure in history. His call had to be grounded on the best observation that good officiating can offer. Swearingen based his ruling on sound officiating principles.

Young football officials learn the rudiments as they preside over Pee Wee games. Jerry Markbreit, along with Alan Steinberg, reflects on his officiating career in his engaging autobiography, Last Call. In it, he describes a fundamental maxim of officiating: “If you think you saw a foul, you didn’t. Never call a foul unless you know.” This means unless an official is certain of what he saw, he didn’t see it.

Since a forward pass consecutively touched by two offensive players was not legal in 1972, an official who clearly and without reservation witnessed it would rule the catch by Harris to have been illegal. He would have whistled the play dead as an incomplete pass. Neither Harder—who had been an outstanding fullback for the Chicago Cardinals—nor Burk did.

To the contrary, they reported that the ball appeared to have bounced off Tatum. Harder and Burk, experienced and highly regarded officials, performed well enough in 1972 to warrant playoff assignments. Had even one official been certain that the ball did not hit Tatum, he would have made the ruling immediately. They wouldn’t have waited to deliberate. Swearingen, as the referee and crew chief, made his decision based on Harder’s and Burk’s best information. And Swearingen didn’t make the call with technical assistance.

“A lot of people put two and two together and said we used replay for the first time. No way,” emphasizes McNally. “We never used replay.”

The speed of Bradshaw’s pass and Tatum’s force at the collision continue to frustrate an exact reckoning of which player redirected the ball. The video record offers no conclusive evidence to prove who hit it. Modern technology hasn’t helped. If remastering the film can’t give an answer, the replay equipment in 1972 couldn’t have.

On several occasions, McNally showed a tape of the play to officials at clinics in which he lectured. “Every time I showed it, I never got to the point where I said, ‘I’m convinced it was this way or that way,’” says McNally. No consensus would emerge from the viewers either.

“What do you men think of it?” McNally would ask the attendees. “It was like a fifty-fifty split all the times it was shown,” he says.

The idea that Swearingen and McNally consulted the replay first came from the game’s television announcers. They speculated that the referee may have been asking McNally what the television footage showed.

The idea took further hold with a story filed by William Wallace for the New York Times immediately following the game. Wallace wrote the following account of the dugout telephone conversation: “‘How do you rule?’ McNally asked. ‘Touchdown,’ replied Swearingen. ‘That's right,’ said McNally. Score one for man’s technology, in this case camera and film.” This apocrypha, over time, has made its way into the game’s legend.

Even 25 years later, a view endured that McNally and Swearingen relied on the replay tape. Myron Cope, the late Pittsburgh broadcaster and writer, revisited the game in an article for the New York Times on December 21, 1997. He wrote that Oakland coach John Madden believed the officials had consulted the television recording. Cope also noted that Oakland sports reporters had written that version as well.

The belief persists, notwithstanding that McNally and Swearingen say it never happened. The idea that officials in 1972 would consider basing the ruling on videotape doesn’t make sense. It would be years before replay would be used as an officiating tool. It also overlooks McNally’s demand for strict adherence to the rules and decorum from his officials.

An oft-used descriptor for McNally’s character is “straight arrow.” Now in his ninth decade, he is still engaged with officiating, and he continues to take the train from his home outside Philadelphia to the league office in New York to look at game DVDs. He also works as an officiating observer for the NFL.

His honesty and unwavering adherence to the rules is affirmed by an independent—and surprising—source: former Houston Oiler and Atlanta Falcon head coach, Jerry Glanville. Glanville holds McNally in the highest esteem. Coming from one known for liberal sieges on NFL officials, Glanville’s praise is persuasive.

“Let me tell you what Art was. If you looked in the dictionary under integrity, Art would be there,” says Glanville. “Art was the best. That guy was undyingly honest and sincere.”

The eminent former NFL referee Jim Tunney once said that McNally is the only man with whom he would play poker over the telephone. McNally was not one to deviate from the rules’ design or procedure.

Moreover, under replay rules that the league would later institute, to overrule Harris’s score would have required indisputable visual evidence that the ball first hit Fuqua. That would have been a tall order in 1972 given that the existing video footage gives anything but conclusive evidence showing what happened.

Another rumor—this one, amusing—surrounding Swearingen’s telephone conversation with McNally has made its way into lore surrounding the play. Swearingen describes the story wherein his purpose in going to the phone was to inquire about stadium security.

“They said I asked, ‘How many cops have you got to get me out of this stadium?’ They say, ‘Five’ and I say, ‘That’s not enough. Pittsburgh wins!’ I’ve seen that story in print too,” Swearingen says with a laugh.

The Immaculate Reception emerged from circumstances combining to elevate it to one of the game’s greatest moments. With any change in the play’s timing, its historical import would have been lost. It also would have made Swearingen’s life simpler.

Had the ball’s deflection to Harris happened earlier in the game, it would have excited the crowd, but no mob would have charged the field. The Raiders would have protested, but to no avail. With the field free of swarming fans, Swearingen might have given the signal for a touchdown upon completing a conference with the crew to reaffirm the call, though such a signal would have been redundant given Burke’s initial indication. But this also assumes that a conference would even have been held—a reasonable possibility given the Raiders’ intense protests. But there would have been no interference from fans,

and there would have been no mistaken suggestion that McNally wanted to talk to the referee.

But with the game in its final seconds and Pittsburgh’s hope all but lost, the emotional reversal was too much for hometown fans. They had witnessed a miraculous play by which their team won a playoff game after frustrating decades. The excitement moved several thousand spectators to overtake the field. They didn’t make Swearingen’s job easier.

In Myron Cope’s reprise, he quoted Madden as having said, “If the officials really knew what happened, they’d have called it right away.” Cope went on to observe: “He had a point.”

Well, not exactly.

First, Burk did signal a touchdown when Harris entered the end zone, followed by the Raiders mounting their protest. Oakland’s outcry begat the conference among the crew—not its indecision.

Those who ran onto the field delayed the discussion. The unleashed fans caused an additional delay before the crew could confer.

When, after having spoken to McNally, Swearingen gave the touchdown signal, it lent to the illusion that he consulted the supervisor for the final ruling. The chance that these events would transpire at any other point in the game than its final seconds ranges from remote to impossible.

While Pittsburgh fans still celebrate the play—a mannequin wearing Harris’s Steeler uniform and depicting the catch greets travelers in the Pittsburgh International Airport—fallout for Swearingen remains. Rancor seems to persist even after more than three decades.

“Madden says I went to the phone to get the instant replay,” says Swearingen. “He thinks I didn’t know what I was doing. I went to the phone because I thought Art wanted to talk to me. Madden has hated me since,” he laments.

But McNally points to contrary evidence. “John Madden never called to complain. He never called to say, ‘Tell me what went on.’”

Twenty-five years later, McNally attended an Eagles game in which the network aired a special feature on the Immaculate Reception. The producer and the director coaxed McNally to visit with Madden, who was there with the broadcast team.

“He never, ever said that it was terrible or that it was wrong,” says McNally regarding his chat with the former Raider coach. “Class, absolute first class,” McNally says about Madden and their conversation.

But Swearingen bears the weight of criticism by those who didn’t like the game’s outcome or who don’t know what really happened that day.

Chapter Three

Judging Chaos

“It’s the hardest game to officiate. It’s not bird watching.”

—Matt Millen, TV Analyst; Former NFL Player and Executive.

“Everything that the officials in the National Football League deal with is in micro inches and milliseconds.”

—Jerry Seeman, NFL Supervisor of Officials, 1991–2000.

Football has many moving parts. And in the NFL, those parts move much faster than they do anywhere else the game is played. The official who comes into the league from high-level college games is surprised at how much quicker the professional game moves.

Turn on the TV, settle into the Barcalounger, and watch the University of Florida play Alabama on Saturday. Then watch any two NFL teams on the same television the following day. The speed of the two events doesn’t seem too different. But watch the same two games from the field level, and you would notice a difference—in a big way.

“The speed of the game is so much different,” says former NFL referee Bernie Kukar. “There is a significant jump in between the skill levels of these guys from major college to the NFL. It doesn’t look that much different on television. But when you’re on the field with them, when you’re trying to run stride-for-stride with these guys, then you notice the difference.”

The exceptionally affable Kukar, an NFL back judge and referee for 22 years, comes from the “swamps of Northern Minnesota,” as he describes the surroundings of his youth. He pronounces his words with the lengthened O’s common to that region’s inhabitants. His denim Levis give him an outdoor enthusiast’s look. He resides on the shore of Lake Superior, possessing what has to be an ingrained resistance to the elements. His easy laughter is a tipoff that he is a man of good humor and that he has enjoyed himself on and off the field.

“If you look at it realistically, there are probably less than five percent of them from the Division One level who make it in the NFL,” Kukar continues. “Look at how many Division One teams there are. You can imagine taking the top three to five percent off of every team in the country and popping them into the NFL,” he says.

Take the players drafted each May and reduce that field by those who actually land on an NFL roster when the season starts. The percentage is modest. With laws of natural selection in effect, those who ascend to play the game as professionals make it a wholly different proposition than the college game, no matter what similarities the television might project.

Matt Millen has spent his adult life in and around professional football. A Pro Bowl linebacker on Super Bowl winning teams in San Francisco, Washington, and Oakland—as well as in Los Angeles, when the Raiders were based there—he also was the CEO and General Manager of the Detroit Lions between his broadcasting career’s start and its resumption with the NFL Network and ESPN in 2009. His unflattering remarks on the air about the officials in 1999 led to his getting a first-hand look at their jobs. The NFL and the Fox Network arranged to have him work as an umpire for a quarter in a preseason game the following year so he could get an idea how the game looked while wearing a striped shirt.

“The avenue into pro football for 99% of the people in our country is the television,” says Millen. “And the television is a really poor avenue because it makes everything relative. The players appear about the same size and they all appear to run about the same speed,” he says. They don’t.

“It’s not until you get down on the sideline or you’re involved yourself that you start to see how violent the collisions are, how fast people are moving, and how big some of these people are,” says Millen.