Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- E-Book-Herausgeber: Jentas EhfHörbuch-Herausgeber: Skinnbok

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

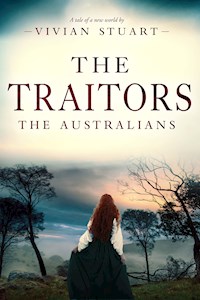

- Serie: The Australians

- Sprache: Englisch

IN THE MIDST OF BLOODSHED AND REBELLION A NEW GENERATION STRUGGLED TO BE BORN... The fifth book in the dramatic and intriguing story about the colonisation of Australia: a country built on blood, passion, and dreams. In the British colony of Australia, the obstacles are challenging and never-ending. The new governor, Bligh — better known for his command on the Bounty and the mutiny against him — has already gained a relentless enemy: The New South Wales Corps, also known as The Rum Corps due to their profitable side business. Governor Bligh's other enemies are the Irish rebels — who wish to end his life! And what will be the fate of Jenny Taggart-Broome now? The hardships of life in the colony, as always, hit "regular" people the hardest. Rebels and outcasts, they fled halfway across the earth to settle the harsh Australian wastelands. Decades later — ennobled by love and strengthened by tragedy — they had transformed a wilderness into a fertile land. And themselves into The Australians.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 476

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das Hörbuch können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

The Traitors

The Australians 5 – The Traitors

© Vivian Stuart, 1981

© eBook in English: Jentas ehf. 2021

Series: The Australians

Title: The Traitors

Title number: 5

ISBN: 978-9979-64-230-5

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

All contracts and agreements regarding the work, editing, and layout are owned by Jentas ehf.

The Australians

The ExilesThe PrisonersThe SettlersThe NewcomersThe TraitorsThe RebelsThe ExplorersThe TravellersThe AdventurersThe WarriorsThe ColonistsThe PioneersThe Gold SeekersThe OpportunistsThe PatriotsThe PartisansThe Empire BuildersThe Road BuildersThe SeafarersThe MarinersThe NationalistsThe LoyalistsThe ImperialistsThe ExpansionistsAcknowledgments

I acknowledge, most gratefully, the guidance received from Lyle Kenyon Engel in the writing of this book, as well as the help and cooperation of the staff at Book Creations, Incorporated, of Canaan, New York: Marla Ray Engel, Rebecca Rubin, Marjorie Weber, Charlene DeJarnette, and, in particular, Philip Rich, whose patience was seemingly inexhaustible.

Also deeply appreciated has been the background research so efficiently undertaken by Vera Koenigswarter and May Scullion in Sydney.

The main books consulted were:

The Life of Vice-Admiral William Bligh: George Mackaness, Angus & Rorbertson, 1931; Bligh: Gavin Kennedy, Duckworth, 1978; Rum Rebellion: H. V. Evatt, Angus & Robertson, 1938; The Macarthurs of Camden: S. M. Onslow, reprinted by Rigby, 1973 (1914 edition); Mutiny of the Bounty: Sir John Barrow, Oxford University Press, 1831 (reprinted 1914); A Book of the Bounty: George Mackaness, J. M. Dent, 1938; Description of the Colony of New South Wales: W. C. Wentworth, Whittaker, 1819; The Convict Ships: Charles Bateson, Brown Son & Ferguson, 1959; Captain William Bligh: P. Weate and C. Graham, Hamlyn, 1972; History of Tasmania: J. West, Dowling, Launceston, 1852; A Picturesque Atlas of Australia: A. Garran, Melbourne, 1886 (kindly lent by Anthony Morris).

These titles were obtained mainly from Conrad Bailey, Antiquarian Bookseller, Sandringham, Victoria. Others relating to the history of Newcastle and Hunter River, New South Wales, were most generously lent by Ian Cottam, and extracts from the Historical Records of Australia were photocopied for me by Stanley S. Wilson.

My gratitude for her efficient help in speeding typescript across the Atlantic goes to my local postmistress, Jean Barnard; and I owe an immense debt of gratitude both to my spouse and to Ada Broadley, who, in the domestic field, made my work 6n this book easier than it might have been.

Truth, it is said, is sometimes stranger than fiction. Because this book is written as a novel, a number of fictional characters have been created and superimposed on the narrative. Their adventures and misadventures are based on fact and, at times, will seem to the reader more credible than those of the real life characters, with whom their stories are interwoven. Nevertheless — however incredible they may appear — I have not exaggerated or embroidered the actions of Governor Bligh, his daughter Mary Putland, John Macarthur, George Johnston, or their contemporaries in retelling the story of Australia’s Rum Rebellion. They behaved in the manner described, although, of course, their dialogue — necessary in a novel — had to be imagined.

In the light of hindsight, opinions differ as to the merits or flaws of Bligh and Macarthur. Each has his admirers and his critics, just as each, being human, has his vices and his virtues ... but it is a fact, which I acknowledge, that John Macarthur played a very prominent and valuable part in rendering the colony prosperous by establishing its wool industry. He also, as this book will illustrate, came perilously near to destroying it, in order to retain the trading monopolies by means of which he and the officers of the New South Wales Corps made their personal fortunes.

Very extensive reading has convinced me that, judged by the standards of their day and age, William Bligh was the more honorable man, John Macarthur the cause of his downfall ... almost single-handed.

It is interesting to note that, of the governors and acting governors who followed the upright and farsighted Admiral Phillip, Colonel Paterson — in a single year — disposed of more land, 68,101 acres, than any who went before him. The rebel administration between Bligh’s arrest and Governor Macquarie’s arrival granted a total of 82,086 acres in, one can only suppose, an endeavour to reward those who gave their support or whose loyalty had to be bought. John Macarthur, however, received a grant of only three acres in the town of Sydney, two of which he exchanged, quite legally, for a similar acreage in Parramatta. Nevertheless, he was the colony’s largest and wealthiest landowner, with a holding of 8,533 acres in all, against Governor Bligh’s comparatively modest 1,345. (See Historical Records of Australia and Mackaness.)

Finally, I should mention that I spent eight years in Australia and travelled throughout the country, from Sydney to Perth, across the Nullarbor Plain, and to Broome, Wyndham, Derby, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Adelaide, with a spell in the Islands and the Dutch East Indies, having served in the forces during World War II, mainly in Burma.

Prologue

Abigail Tempest watched in unhappy silence as her father set spurs to his horse and cantered off down the long, weed-grown drive. She waited until he was out of sight and then said, her forehead still pressed against the glass of the window, ‘Papa has gone, Rick. I was so hoping that he would change his mind ... because he promised, you know. He gave me his word.’

Her brother, Richard, came to stand behind her. He was in naval uniform, wearing the white patches of a midshipman earned after two years at sea as a lowly volunteer. He eyed her bent fair head a trifle sceptically. He was seventeen, only a year older than Abigail, but already he was more than a head taller than she was and, in his considered opinion, vastly her senior now in worldly experience.

At pains not to sound condescending he said, ‘You don’t understand, Abby. Papa could not refuse an invitation from Lord Ashton. He’s a rear admiral and Papa’s patron and besides he—’

‘A retired rear admiral,’ Abigail pointed out. ‘And poor papa doesn’t need a patron to advance him in the naval service now, does he?’

‘No,’ her brother conceded, ‘but I do. It is thanks to his lordship’s influence that I have been appointed to the Seahorse. She is a forty-two gun frigate, you know.’

‘With the country at war, you would have had no trouble finding a berth,’ Abigail assured him.

She turned from the window to face him, and Richard was shocked when he glimpsed the pain in her eyes. She was such a pretty girl, he thought, with her slim, lithe body and shining, corn-coloured hair ... pretty and talented, possessed of a charming singing voice and no little skill at the piano. On the threshold of womanhood, she should have been carefree and happy, with a host of admiring young beaux, vying for her favours, but instead ... He sighed, reaching for her hand as she went on bitterly, ‘They will play after dinner, Rick—they always do. And for high stakes, which Papa cannot afford.’

‘He might win,’ Rick offered, but without conviction.

For answer, Abigail gestured to the sparsely furnished room behind them. ‘Can’t you see ... are you blind? The pictures have gone, all Grandpapa’s books and Mamma’s cherished china—even the cabinet she loved so much, the one Thomas Sheraton made. I know you’ve been away for two years, Rick, but surely you’ve noticed how different things are now?’

‘I did notice that there were only three horses in the stable,’ Richard admitted, ‘and no carriage. But—’

‘They were all sold,’ Abigail told him. ‘The bailiffs came, three weeks ago, to take Mamma’s cabinet and the piano away. They would have taken poor little Lucy’s silver christening cup if I hadn’t forbidden it. They were sent by the court on Mr Madron’s behalf—he applied for a court order.’

‘Madron? You mean the feed merchant, that Madron?’

‘I mean his son, Reuben. Old Tobias Madron has retired. Reuben claimed that papa had not paid his account for horse and cattle fodder for twelve months.’ Abigail spread her hands in a despairing gesture, and Richard’s heart sank as she continued the unhappy litany. ‘At least Reuben Madron does not need to worry any more about being paid, for there are no cattle to feed now. Papa sold the last two farms at the beginning of the month, and the three horses we have left have to live on hay.’

‘But ... Papa’s not in debt now, is he? Surely if he’s sold the farms, he must have paid off whatever he owed?’

Abigail’s lower lip trembled, and hanging on her answer, Richard saw her shake her head. ‘He still owes money for gaming debts. I don’t know how much, he will not tell me. Rick dear, you have not heard the worst of it yet.’

‘Have I not? Then tell me, for pity’s sake!’

She hesitated, eyeing him uncertainly. ‘Papa said nothing to you? He gave you no hint of his—his plans for the future?’

‘No,’ her brother denied. ‘Dammit, Abby, I only arrived here yesterday afternoon. He’s hardly spoken to me of anything—except my voyage. He wanted to hear about that, and I told him, naturally. There wasn’t time for much else, and I was dropping with sleep. But ... well, he talked to me of Mamma, of course. He told me how bravely she had borne her last illness and how much he misses her. And he does, Abby, truly . .. he was in tears when he spoke of her.’

‘I know that,’ Abigail responded, her voice flat. She turned away from him and walked over to one of the wing chairs drawn up in front of the spluttering log fire. The fire gave off little heat, and she poked at it resentfully before adding another log. Over her shoulder, she added, ‘We all miss her, Rick. It ... Oh, it might have been different if Mamma had lived, so different! Papa listened to her. He took her advice, but he will not listen to me. He says I am a child.’

‘And are you not?’ Richard quipped, thinking to make a joke of it in the hope of bringing a smile back to her lips. The joke fell flat. Abigail shook her head. The fire woke at last to a semblance of life and she seated herself in the wing chair, holding out both hands to the blaze she had created.

‘No,’ she asserted. ‘I am not a child any more. In the—in the situation in which I find myself, I cannot afford to be. Papa is not himself, Rick. That terrible head wound he suffered at Copenhagen has affected him very badly, and it is getting worse. Whilst Mamma was alive, and during her illness, he kept himself in check, for her sake. Oh, he was drinking then, quite heavily, and gaming with his friends but not to—not to excess. He was hoping, I think, when the war with France was resumed, that Their Lordships of the Admiralty would have need of his services. He wrote, he waited on the First Lord, but they would not give him another ship.’

‘He’s not fit to serve at sea,’ Richard put in when she paused. He came to sit opposite her. ‘Go on, Abby. You mentioned his plans for the future, but you haven’t told me what they are.’

‘I’m coming to that,’ Abigail promised, ‘but I want you to understand, to realise how Papa has changed. He ... the last time he went to the Admiralty was when Mamma was still alive. He stayed in London for almost a week and someone, a friend he met there, introduced him to a gaming club. It’s called White’s, I believe, and the Prince of Wales goes there, with a lot of very wealthy noblemen, so the stakes are high. He ... Rick, Papa won—he won a great deal of money. I remember, when he came home, he bought a new hunter for himself, and a dogcart and a beautiful little pony for Mamma. He said she could go for drives in it, when she—when she got better. Only—’ She broke off, a catch in her voice.

Only his poor Mamma had not got better, Richard thought. And probably his father had never won so substantial a sum again. He had gone on playing, but he had become a loser. The evidence of this was, as Abby has indicated, all about them. He glanced up at the walls where the pictures had hung, family portraits, for the most part, and mainly of his mother’s family. There were lighter squares on the wallpaper in the spaces which the pictures had occupied, smudged stains in the corner in which the Sheraton china cabinet had stood. He had not noticed these signs when he had first entered the room—he had been too pleased and excited by his homecoming, too eager to retail his own adventures to observe the change in his father.

Looking back, however, he realised that there had been a significant change. The maudlin tears, the amount of brandy his father had consumed as they talked, his explosive burst of ill temper when one of the slovenly servants had interrupted them ... these had all been indications which he had observed and chosen to ignore, together with the fact that the servants were slovenly and that there were now very few of them.

Most significant of all, he supposed, had been the manner in which his father had taken leave of them, only a short while ago. The boy frowned, remembering. Normally the most courteous of men, Edmund Tempest had rebuked Abby when she had sought to persuade him not to accept the admiral’s invitation, and he had barely acknowledged his own son’s presence. And when thirteen-year-old Lucy had come running down the steps from the front door to wave to him, Edmund had ordered her brusquely back to the house, seemingly indifferent to the tears his harsh words had provoked.

Abigail was crying now ... silently, trying to hide her face from her brother. His own throat tight, Richard went to kneel at her feet, taking her thin little hands in his. ‘You had better tell me the rest, Abby,’ he urged. ‘I shall have to know, shall I not—even if Papa has not seen fit to confide in me? What plans has he made?’

She made a brave attempt to speak calmly. ‘He intends to go out to Botany Bay to settle, taking Lucy and me with him. To—to start a new life, he says. You are provided for. So he will sell this house lock, stock, and barrel—all we have left—in order to raise the capital he will require and to pay the cost of our—our passages.’

Richard stared at her in stunned disbelief.

‘Botany Bay? But that is a penal colony! And it’s half the world away! It’s ... for God’s sake, Abby, whatever put such an idea into his head? Has he ... has Papa taken leave of his senses?’

‘There are times when I truly fear he has,’ Abigail confessed. She lifted her tear-wet face to his. ‘He has changed so much, Rick! But ... as to what put the idea into his head, he met an officer who is on sick leave from the colony. A Major Joseph Foveaux of the New South Wales Corps—he is staying as a guest of the Fawcetts at Lynton Manor. And,’ she added wryly, ‘I fancy he will also be dining at Lord Ashton’s this evening—they say he is a very good card player. Certainly Papa has spent a great deal of time in his company since his arrival here, talking to him of conditions in the colony.’

‘But it is still a penal colony,’ Richard objected. ‘What sort of new life would that offer?’

‘A very good one if Major Foveaux is to be believed,’ Abigail answered. ‘He appears to have made a fortune there—on the mainland first of all, where he owned two thousand acres of land, and then in command of an island over nine hundred miles away—a place he calls Norfolk Island. He told Papa that the worst and most recalcitrant of the convicts are sent to the island—those who rebel or try to escape from the principal settlement at Sydney.’

‘And Papa plans to go there?’

‘No, not to Norfolk Island—to Sydney. It seems that all who go out there as free settlers are allocated as much land as they want at a purely nominal price, with convict laborers to cultivate it in return only for their keep. Major Foveaux has assured Papa that he cannot fail to show a most handsome profit if he brings out livestock of good quality for breeding, and joins one of the trading syndicates which the corps officers have organised. Jethro Crowan, the shepherd Papa engaged at Michaelmas, is to come with us as foreman and to care for the livestock on the voyage.’

Richard was silent, endeavouring to assess and evaluate the prospects his sister had outlined. For his father, perhaps, they were hopeful, even—in his present circumstances—desirable, but for Abby and for the delicate little Lucy ... He got up abruptly and started to pace the floor, a prey to deep misgiving.

‘Do you want to go, Abby?’ he asked at last, returning to face her.

‘Oh, Rick, of course I don’t!’ Abigail answered miserably. ‘This is my home—I’ve never lived anywhere else and neither has Lucy. I dread the very thought of leaving England! And besides that, New South Wales is a terrible place from what I have heard of it. They say there are black savages there, as well as the lowest kind of convict felons, and it must be true since Major Foveaux does not deny it.’ She shivered. ‘And, Rick, that monster Captain Bligh of the Bounty is governor ... imagine it!’

‘Papa admires Captain Bligh, Abby,’ Richard felt compelled to point out. ‘He has always said that his conduct at Copenhagen was little short of heroic. And even Lord Nelson singled him out for approbation. He—’

Abigail sighed. ‘I’ve not said I will not go, Rick ... only that I do not want to. If it will help poor Papa, if it will provide a new life for him and enable him to pay off his debts, then I cannot think of myself. If he goes, Lucy and I must go with him. In any event,’ she added resignedly, ‘we shall have no choice, shall we?’

That was true, Richard thought. If his father had really made up his mind to sell up and leave England, the two girls could hardly stay without a roof over their heads or anyone to support them. He, alas, could not afford to maintain them on a midshipman’s meagre pay. He could barely support himself, even when he was at sea. And the country was at war, the navy in the thick of it. He might be killed or severely wounded, as his father had been. Like his father, he might be invalided out of the service, cast ashore without hope of further employment, to exist as best he might on the pittance Their Lordships deemed sufficient compensation for their junior officers.

His father had had this house and a well-endowed estate, which he had inherited, as well as a first lieutenant’s wound pension. But he himself would have nothing once the house was sold ... and it might be years before he obtained his lieutenant’s commission.

Abigail said gently, as if she had read his thoughts, ‘We are not your responsibility, Rick. You have your career, and I thank God that you have.’ She managed a wan little smile. ‘Dear Rick, it is so good to see you again! And a great relief to have someone in whom I can confide—someone who can understand my anxieties concerning Papa. I could not talk to Lucy as I have to you. She is so sensitive, and she worships Papa. She—’

‘You used to worship him, too, Abby,’ her brother reminded her.

‘Yes,’ she agreed, without warmth. ‘I did.’

Her use of the past tense was indication enough of her feelings, and Richard sighed, bitterly conscious of his own helplessness in a situation that affected them all so poignantly. ‘I wish I could do more to aid you, I ... When does Papa plan to leave? Or has he not yet decided?’

‘Oh, he has decided. He told me a week ago that he has booked passage for all three of us and Jethro on board a ship called the Mysore. He said she is an Indiaman of four hundred tons burden and that her master, Captain Duncan, has assured him that she will make a fast passage. But’—Abigail shrugged despondently—‘it will still take us about six months to reach Sydney, will it not?’

Richard nodded. ‘I believe so. Some ships do it in less.’ The Mysore was probably a convict transport, carrying a few fare-paying passengers in upper-deck cabins. Most of the ships plying between England and New South Wales were hired by the government to transport convicted felons to the colony, he knew, but anxious not to upset his sister, he refrained from saying so. Time enough for her to find that out when she went on board, poor girl ... At least such transports were now required to carry a surgeon, to ensure that the convicts were properly fed and cared for, and the conditions in which they travelled had been improved.

‘When is the Mysore due to sail, Abby? And do you know from which port?’

‘In three or four weeks’ time, I think,’ she told him. ‘And she is at Plymouth—she had just docked there when Papa called on her master. At least that will mean a short journey—the Bodmin coach stops at Half Way House now.’

‘Good,’ Richard approved. ‘I may be able to see you off. The Seahorse is refitting at Devonport, and I’m told she will be joining Lord Collingwood’s flag in the Mediterranean when she’s completed.’ He talked of his ship more to gain time and to introduce a change of subject than because he expected Abigail to share his enthusiasm, but she made a selfless attempt to do so, and only when the subject was exhausted did she return to that of their father.

‘Rick,’ she said, with a catch in her voice, ‘I don’t believe that, in his heart, Papa wants to leave England or to sell this house. He was brought up here, just as we were, and I know he loves the place as much as we do. It will be so different in New South Wales for him and for us. I ...’ She hesitated, again eyeing him uncertainly and clearly wondering whether or not to confide in him further.

Richard reddened. ‘You can trust me, Abby,’ he assured her. ‘I’ll not repeat anything you do not want me to—least of all to Papa.’

She accepted his assurance and went on almost eagerly, as if it were a relief to unburden herself, ‘As I told you, Papa has been talking to this Major Foveaux, who is all enthusiasm for the prospects Sydney offers. But I ... that is, I sought another opinion—a woman’s, Rick—and as I feared, it was much less favourable than Major Foveaux’s. That was how I found out about the black savages—they call them Aboriginals, and it seems they rob and murder at will in the isolated settlements which have no troops to guard them.’

Richard stared at her incredulously. ‘A woman told you that? But where in the whole wide world did you contrive to find a woman who knew anything about Sydney, pray?’

Abigail smiled, savouring her small triumph, ‘Oh, quite near at hand as it chanced ... in Fowey village. A Mary Bryant, who is a widow and something of a local celebrity. I had heard her talked about, so I went to see her, and—’

‘But Fowey’s fifteen miles from here!’ her brother interrupted. ‘How did you manage to get there and back without Papa knowing?’

‘I drove the governess-cart, with the old pony, Pegasus. He’s slow but reliable. Papa thought I was going to St Austell to visit the Tremaynes, as I often do, so he raised no objection. It was after eleven when I got back, but Papa was out so it didn’t matter.’ Abigail shrugged off her deception as of no account, but her smile faded as she added, ‘In a way I am sorry I went. The picture Mrs Bryant painted of the colony was—oh, it was horrible, Rick! I’ve had nightmares about it ever since. She said that Sydney town was a veritable den of iniquity and the convicts cruelly maltreated and made to work in chains. They—’

‘Was this Mrs Bryant a convict?’ Richard asked suspiciously.

‘Yes, she was, but she is a most respectable woman, truly, Rick, and she received the king’s pardon. She told me that she was one of a small party, organised by her husband, which escaped in an open boat—a sailing cutter, I think she said—to Timor, in the Dutch East Indies. Poor woman ... she lost both her babies, as well as her husband, on the voyage home.’

Memory stirred and Richard slapped his thigh, suddenly excited. ‘Why, Abby, she was a heroine! I heard the story—our first lieutenant was talking about it not very long ago, when he was instructing some of us in navigation. He said it was an epic ... a feat of navigation that even put Captain Bligh’s passage from Tofua into the shade, because it was longer and the Bryant party had only a compass to aid them. Their navigator was a man named Broome—or some name like that—and he’s serving in the navy now, as a master’s mate. But—’ He broke off, sensing Abigail’s lack of response and then added, thinking once again to offer her consolation, ‘it was a long time ago—fourteen or fifteen years at least. They escaped when Admiral Phillip was governor. Conditions will have changed, they’ll have improved, I’m quite sure. After all, from what I’ve heard, free settlers are going out to Sydney now in increasing numbers. And I doubt if a taut hand like Captain Bligh will permit the town to remain—what did your Mrs Bryant call it?—a den of iniquity—for long.’

Abigail’s brows met in a thoughtful pucker. ‘Perhaps you are right, Rick,’ she allowed, ‘but there is someone else I can ask—Mrs Bryant told me of her. A Mrs Pendeen, who is the wife of the vicar of St Columbia’s in Bodmin. She was Bishop Marchant’s daughter, and she returned more recently from Sydney, I believe. She—’

‘At least she wasn’t a convict,’ Richard put in, relieved. He held out both hands to her, and Abigail took them, rising from her chair to stand facing him. Mary Bryant had hinted that the bishop’s daughter had, like herself, been granted a royal pardon, Abigail recalled ... but she had doubted this, supposing the woman to have been confused. In the light of Rick’s observation, her doubts returned. Old Bishop Marchant had died a long time ago, during her own early childhood, but he was still talked of as a much-loved and widely respected—even saintly—man. It was absurd to imagine that his daughter, who was now the wife of a Church of England vicar, could possibly have been transported to New South Wales as a convicted felon.

She shook her head and answered, with certainty, ‘No—no, of course not. That is why I want to see her. Will you come with me, Rick? You could make some excuse to Papa, and he wouldn’t question it if we went together.’

‘In the governess-cart, with old Pegasus between the shafts?’ Richard questioned wryly. ‘It would take us all day to get there!’

‘We can go with the carrier’s van from St Austell if we leave early,’ Abigail insisted. ‘Oh, please, Rick—do say you will.’

He smiled down at her. ‘I’ll come,’ he promised, ‘if it matters so much to you Abby dear.’ It was borne on him, as he spoke, that if his entire family went to New South Wales he might never see them again. A lump rose in his throat, and as his glance went to the shabbily furnished room, with its pictureless walls and the denuded bookshelves, he found himself, for the first time in his life, bitterly critical of his father. Like Abby and little Lucy, he had worshipped and looked up to both his parents, but now ... His fingers tightened about his sister’s thin, work-roughened hands.

‘Perhaps,’ he suggested, ‘perhaps Papa will have a big win at the tables tonight and then all our fears will be groundless.’

‘That is what I pray for,’ Abigail confessed. She avoided his gaze, two bright spots of colour rising to burn in her cheeks. ‘One should not ask Almighty God for such—such mundane things, I know, but it is what I ask Him, every night, Rick. I pray that Papa may win enough to enable us to stay here and’—she looked up at him then, her lower lip tremulous—‘I prayed for your safe return. He has granted that prayer, but I fear He will never grant the other one.’

‘In His wisdom and mercy, He might,’ Richard said but without conviction. He tucked his sister’s hand beneath his arm. ‘It’s time we dined, is it not? Let’s go and find Lucy and enjoy a meal together ... poor little scrap, we’ve been neglecting her, and she’ll take it amiss. We’ll put the clock back, shall we, and pretend, just for this evening, that nothing has changed?’

Play at the loo table had started at a little before midnight following a late and somewhat protracted dinner at Pengallon House, and after fewer than a dozen hands it had been agreed, at Major Foveaux’s suggestion, that the pool should be unlimited.

Now, with the first glimmer of light seeping in through an uncurtained window at the far end of the musicians’ gallery and the candles in the room below spluttering to extinction, a fortune was at stake. Each of the red counters in the pool represented a bid of three hundred guineas, the whites a hundred, and bidding had, from the outset, been high.

Conscious of his obligations as host to the party, Lord Ashton was worried, although less on his own account than that of his guests. He had retired from the Royal Navy as a very rich man, with the rank of rear admiral and, after a two-year command in the Caribbean, an enviable share of his squadron’s prize money accredited to him. But ... He frowned, looking across the table at Edmund Tempest’s downcast head.

The poor devil had elected to play the widow in the previous deal and failed to win a single trick, and his hand was shaking as he paid his forfeit from the dwindling pile of red counters in front of him.

‘Foveaux,’ he began sourly. ‘Damme, you—’

Fearing an outburst, Lord Ashton waved to a footman to replenish the candles in the chandelier. As the man hastened to obey him, he himself turned up the wick of the oil lamp at his elbow and moved it with careful deliberation to the centre of the table, so that its light shone on the accumulation of counters there and on the two packs of cards the players had been using.

‘We’ll have fresh cards and another decanter,’ he instructed his major-domo, and when these were brought, he added, his tone intentionally jocular, ‘A plague on you, Major! You’ve the luck of the very devil, have you not? Who’d have imagined that you would come up with two flushes in a row, eh?’

‘Who indeed, sir?’ Major Joseph Foveaux met his host’s quip with a smile that bordered on complacency, but his dark eyes were wary. He was a handsome man in his early forties, running a little to seed, and was, the old admiral knew, on leave from the penal colony in New Holland, of which his regiment—the New South Wales Corps—formed the military garrison. He had lately acted as lieutenant governor of some outlying settlement, Arnold Fawcett had said ... and it had been an appointment that had paid him generously, judging by the stakes he played for and the style he affected, although the corps to which he belonged had a less than distinguished reputation. It was an infernal pity that poor Edmund Tempest had allowed himself to get mixed up with Foveaux, in the circumstances, but ... Lord Ashton gave vent to an audible sigh.

Major Foveaux went on, quite pleasantly, as he made change with white counters to enable the pool to be divided, ‘You know what they say concerning one’s luck at cards, Admiral. Mine, alas, seems at present to be confined to the gaming table, and I fancy they were glad to see the back of me at Boodles! His Royal Highness certainly was. But if one’s on a winning streak, one must see it through ... and count one’s lack of success with the fair sex as a small price to pay. My own wife’s displeased with me, and Edmund’s lovely daughter won’t give me the time of day, damme!’ He snapped the seal on one of the new packs and, still smiling, thrust it in Tempest’s direction. ‘Be good enough to shuffle the cards, Edmund. It’s Judge Grassington’s deal, I believe.’

Edmund Tempest did as he had been asked with sullen clumsiness and reached for his glass without speaking. The pack lay waiting for Lord Ashton’s cut, but he delayed restarting the next hand, resenting Foveaux’s ill-mannered eagerness to continue a game in which only he was a major winner. Such behaviour smacked of an ungentlemanly lack of sensitivity, but then, the admiral reminded himself, Joseph Foveaux was noticeably lacking in the finer feelings that came with breeding.

Rumour had it that he was a by-blow of the Earl of Ossory and that his mother had been employed in the Ossory kitchens ... a damned Frenchwoman, if the rumour were to be relied upon, and it probably was. Lord Ashton repeated his sigh and cut the cards. He had not taken to the fellow from the start of their brief acquaintance, he reflected, but since he was a guest of the Fawcetts, it was impossible to avoid meeting him socially, at the houses of friends or in the hunting field—Arnold Fawcett took him everywhere and Tempest, too.

This was the third or fourth occasion on which they had encountered each other at the loo table, and the last two occasions had proved costly enough. Tonight, though, his luck was almost beyond belief. Lord Ashton made a swift mental calculation. The last two hands alone had netted Ossory’s dammed scallywag of a son a cool two thousand guineas, the losers himself, Fawcett, and Edmund Tempest, who—poor feckless devil—was the least able to afford such a loss though of course it was his own fault.

‘Judge Grassington,’ Foveaux persisted, ‘the cards are yours, sir.’

‘Why, ’pon my soul, are they?’ Old Judge Grassington, who had been nodding, roused himself to peer uncertainly at Foveaux over the top of his thick-lensed glasses. In addition to being short-sighted, the judge was deaf, and for the past hour he had taken little part in the play save when it fell to him to deal.

He had not lost, however, Lord Ashton observed without surprise. Grassington might be over seventy and inclined, as the night wore on, to lapse into a doze—a habit acquired during his years on the bench—yet for all that his passing had been shrewdly calculated, and when he did elect to stand, he invariably took sufficient tricks to ensure him a share of the pool. But now it was evident that he, too, was out of patience with the overly lucky visitor from New South Wales. He tugged a heavy gold timepiece from the pocket of his brocade waistcoat and clicked his tongue in well-simulated astonishment, as if only just aware of the lateness of the hour.

‘Have to go, Gilbert, me dear feller,’ he announced without apology. ‘Cash me out, Major, if you please.’ He rose ponderously to his feet, a restraining hand on Admiral Ashton’s shoulder as his host also rose, prepared to escort him to the door. ‘No need for you to disturb yourself ... carry on with the game. Your man can call me carriage and see me on me way. Don’t want to break up the party, you understand, but I’m not as spry as I used to be. Can’t keep awake and that’s the truth, damme!’

Lord Ashton, with a rueful glance at his own depleted stake, was about to use the judge’s departure as an excuse to end the game when Foveaux, anticipating his intention, slid the pack across the table and said smoothly, ‘Then I fancy it’s your deal, Edmund, is it not?’

Edmund Tempest raised bloodshot eyes to meet his reluctantly, his pulse visibly beating at the centre of his hideously scarred left temple. He had sustained the ugly head wound six years before at the Battle of Copenhagen when serving as first lieutenant of poor Robert Mosse’s seventy-four, H.M.S. Monarch, the admiral recalled ... Indeed, as his patron, he had obtained Tempest’s appointment for him, hoping to afford him the chance to make post rank.

He had been able enough as a young officer—promising even—but since then the wretched fellow had steadily let himself go to the dogs. He had been deuced unfortunate, of course. First he had been invalided by his wound. Then his wife had died not long after his return to his native Cornwall, leaving him with a son and two young daughters. The boy was all right, he was in the navy, but both girls were little innocents of less than marriageable age—pretty as pictures, the pair of them. They did not deserve to be in the straits to which their father had reduced them.

A footman, unbidden, refilled his glass, and Lord Ashton sipped at it, scowling, as Tempest picked up the cards after a moment’s hesitation, his cheeks turned brick red. The fool had started to gamble heavily of late, with a lack of success that was becoming notorious. The small estate he had inherited was now, if local gossip had not exaggerated, partially in the bailiffs hands, with farms sold off and the manor house denuded of furniture and pictures. Yet Edmund Tempest went on playing, presumably in the hope of a miracle which would enable him to recoup his losses.

Recently, he had talked of going out to New South Wales—an idea, no doubt, that Foveaux had put into his head—and watching him now, the old admiral found himself wishing that the wretched fellow would summon up all his resolution and go since it might be the saving of him.

It had been a grave mistake to permit him to take a hand at the loo table tonight, but Tempest had been with the Fawcetts when the invitation had been issued, casually, at Judge Grassington’s garden party the previous week, and had taken it to include himself. Short of insulting him publicly, there had been no way in which his participation could be avoided and, even with the best of motives, one could not insult an old friend and onetime protege. But for all that ... Lord Ashton opened his mouth to utter a warning, only to close it again when Judge Grassington forestalled him.

‘Edmund, me dear boy,’ the old man said quietly. ‘I promised you a lift, did I not? Almost forgot but there’s a sea mist set in, his lordship’s man tells me. Not a night to ride across the moor in evening dress, and since I gave your little Abigail me word that I’d see you safely home, I fancy we’ll both be in her bad books if I don’t, eh?’

Tempest did not raise his head. ‘Abigail has no call to concern herself with my safety, the impudent chit!’ he retorted, his tone peevish. Then, belatedly recalling that the old judge had been his wife’s uncle, he managed a surly apology. ‘I cannot possibly leave the game now, sir. Plague take it, my luck must change!’ He started to deal, and Judge Grassington shrugged resignedly. He moved toward the door, and Lord Ashton, with a curt, ‘Excuse me, gentlemen,’ to the players went with him.

In the long, stone-flagged hall, out of earshot of the players, the white-haired judge said explosively, ‘Damme, I did me best, Gilbert! But I can’t drag the demmed idiot out by the scruff of his neck, can I?’

‘No, unhappily,’ Lord Ashton concurred. ‘And I can’t throw him out. I’ve known Edmund all his life—took him with me into his first ship when he was ten years old.’

The judge accepted his hat and cane from a hovering footman and let the man drape his cloak about his shoulders. ‘It’s those poor little gels of his I’m sorry for,’ he asserted. ‘Abby’s got plenty of spirit, but ... d’you suppose he really intends to take ’em off to—what’s the name of the demmed place? Botany Bay, New South Wales, or whatever it calls itself?’

‘It might be the best thing he could do, Henry.’

‘You think so? A plaguey penal colony, for God’s sake? When I think of the rogues I’ve had to send out there, I ... demmit, Gilbert, I question Edmund Tempest’s sanity, before heaven I do!’ The old judge’s rheumy eyes were bright with anger as he added, lowering his voice a little, ‘That feller Foveaux’s no advertisement for the place, is he? Arrogant, ill-mannered upstart and too demmed good at cards into the bargain. He took two hundred guineas off me before I’d taken his measure. Feller’s a bluffer, of course—bids on nothing if he thinks he’ll get away with it. Well ...’ He extended a bony hand. ‘Thanks for your hospitality, Gilbert. Though if I said I’d enjoyed meself, I’d be a demmed liar, I’m afraid.’

Lord Ashton escorted him to his waiting carriage and stood watching it drive away, his heavy dark brows knit in a thoughtful frown. The new day was already well advanced, he observed, a grey bank of clouds to the eastward tinged with pink and the sea mist swirling in across the open moorland without a breath of wind to disperse it. There would be rain before long, he thought, conscious of a twinge in his gouty right foot ... the blasted thing always made its presence painfully known when there was rain in the offing. He started to pace the gravelled drive, still deep in thought and then, his mind made up, he strode purposefully back to the house.

To the devil with the obligations of hospitality ... If the only way to save Edmund Tempest from himself required him to dismiss his guests in summary fashion, then by God he would do it! Both Arnold Fawcett and his brother Arthur had lost a fair sum between them—they would not mind, and if Foveaux objected, then to the devil with him, too. The infernal bastard could have no cause for complaint on the score of his winnings, which had been substantial by any standards ... even by Boodles’s and, damn it, the prince’s.

Besides, the admiral told himself wryly, like old Henry Grassington, he pitied Tempest’s two girls.

‘Serve hot chocolate at once, Scorrier,’ he ordered his major-domo, ‘and warn ’em in the stables. We’ll call it a night.’

But when he returned to the withdrawing room, it was to find a remarkable change in the atmosphere. Foveaux was scowling and biting his lower lip; the two Fawcett brothers sat with their mouths almost identically agape, and Sir Christopher Tremayne, normally the most phlegmatic of men, who talked very little when he was playing cards, was offering effusive congratulations to Edmund Tempest. And Tempest, the admiral saw to his astonishment, had—judging by the pile of red counters in front of him—more than recouped his earlier losses. He was dealing, and one after another, every player passed, except Foveaux, who said ill-temperedly, ‘I’ll take the widow and a plague on it! Your luck can’t hold much longer, Edmund.’

‘Can it not?’ Tempest retorted. ‘Well, we’ll see.’

His voice was slurred; the scar on his temple pulsating and inflamed. He had evidently been drinking more heavily than any of the others and his hand was shaking uncontrollably as he extended it to take Foveaux’s original cards. The rules of the game called for the discards to be placed at the bottom of the pack by the dealer, but Edmund Tempest’s attempt to do so was so maladroit that two spilled onto the floor. One, Lord Ashton noticed, was a heart; the eight or the nine, he could not be sure which as, with a smothered exclamation, Tempest bent to pick them up and Foveaux said rudely, ‘Clumsy oaf!’

‘For the Lord’s sake, I ...’ Tempest faced him, red of face and angry, but to Lord Ashton’s relief, he controlled himself and gestured to his stake in the pool. ‘I’m ready to double that, if you wish, as my forfeit.’

‘Then be so good as to do so.’

Three more red counters joined the three in the pool; Foveaux matched them, his expression oddly tense. ‘Make your lead,’ Tempest invited.

A footman, with the major-domo at his heels, brought in the chocolate the admiral had ordered, but he waved them both away impatiently, his gaze riveted to the table.

Foveaux led the queen of clubs and Tempest took it with the ace; his own lead of the king of hearts found his opponent with a void. He took the trick and his fingers closed about the top card of the pack.

‘Hearts are trumps, Joseph,’ he stated thickly and laid down his hand. ‘You are looed.’

‘Hold hard!’ Joseph Foveaux snapped. ‘That card you just turned up, the nine of hearts, was in the hand I discarded. It was one you contrived to drop on the floor. For God’s sake—’ He appealed to the table at large. ‘Did none of you see it? You must have done!’

Silent headshakes were his answer; Lord Ashton hesitated, torn between his own strong sense of justice and his dislike of the upstart Foveaux. To speak now would be to bring about Edmund Tempest’s ruin, he was unhappily aware. He had only glimpsed the fallen card, he could not be sure. Foveaux’s next words decided him to join the others in their silence.

‘Damn your eyes, Tempest!’ the New South Wales Corps officer accused, his expression ugly. ‘You tried to cheat me!’

Before Tempest could speak, the admiral intervened. ‘My house is not to be made the scene of an unseemly quarrel,’ he warned them coldly. ‘Major Foveaux, I will thank you to take your leave forthwith, sir. Divide the pool between you and let’s hear no more of these unpleasant accusations, if you please. The game is over.’

‘As you wish, sir,’ Foveaux acknowledged, his mouth a tight, hard line. He picked up his stake from the pool, cashed himself in, and added in a low, furious voice, ‘You’ve not heard the end of this, Tempest, by heaven you haven’t!’

‘My seconds will wait on you,’ Edmund Tempest began. ‘You—’ But once again the admiral cut him short. The Fawcetts departed with their guest; Sir Christopher Tremayne wrung his host’s hand with unusual warmth and followed them, and Tempest was making for the hall when Lord Ashton called him back.

‘He was right, was he not, Edmund?’ the admiral questioned sternly. When the younger man attempted to bluster, he added in a tone that brooked no argument, ‘I saw the card you dropped.’

‘It was only that one hand, sir, I swear it. My luck changed after you left the room ... I was winning, I had a phenomenal run of the cards. Believe me, I—’

‘You will not be welcome in my house again, Edmund. Nor, I dare swear, in any house in this neighbourhood. Foveaux will talk, so will Arnold Fawcett.’

‘But, sir ... if your lordship would listen.’ Tempest’s hectic colour had faded; he was white and shaken, the admiral saw, guilt and shame written all over him. ‘I beg you, sir ... I’m telling you the truth. I saw the card fall, and I was tempted, but I—’

‘Spare me your excuses,’ Lord Ashton bade him. He drew himself up to his full, impressive height, making no effort to hide the disgust he felt. ‘You’ve made plans to go out to New South Wales, have you not? You’ve booked passage out there, for yourself and the girls?’

Taken aback, Tempest nodded. ‘Yes, in the Indiaman Mysore, sailing from Plymouth, but—’

‘Then the best advice I can offer is that you take them up, now, at once. Go on board as soon as you can and don’t show your face in these parts again if you can help it. I’ll take care of your boy. And for God’s sake, man’—the admiral’s voice softened, became almost pleading—‘make something of your life when you get to Botany Bay, so that those two little girls of yours don’t have cause to feel ashamed of their father.’

‘I ... I’ll do as you say, sir,’ Edmund Tempest promised. ‘But there’s my house. I have to sell it, and—’

‘I’ll have my lawyers deal with the sale. If you leave before the legal details are completed, I’ll have a draft for the proceeds sent out to you.’ The admiral turned his back, feeling tears well into his eyes. The pity of it, he thought ... Edmund had been a credit to the service as a young officer and, in the early days, like a son to him. But now ... ‘Get out of my sight,’ he ordered harshly.

When he had his emotions under control again and turned round, Edmund Tempest had gone.

1

It was still an hour before sunrise on the morning of 28 July 1807, but already Captain William Bligh, Royal Navy—governor and captain general of the penal colony of New South Wales—was at his desk. Mail from England, which had been delivered the previous evening by the master of the convict transport Duke of Portland, lay neatly stacked on his desk to await his attention, but the governor gave only a cursory glance at seals and handwriting, in order to identify the senders.

There was an official dispatch from the Colonial Secretary, William Windham, he saw and, among a pile of private correspondence, a bulky missive from Sir Joseph Banks and a slimmer package, with his wife’s carefully executed copperplate on the outside, which he slipped into the pocket of his uniform tailcoat, to read later at his leisure.

Most of the news would be old, he knew, and Windham’s instructions probably out of date, for the Duke of Portland—although she had sailed direct from Falmouth—had made a slow passage. But her master, John Spence, had brought out his entire consignment of one hundred and eighty-nine female convicts alive and in good health and this, God knew, redounded greatly to his credit. Virtually every transport lost upwards of a score of her unwilling passengers during the long voyage to the place they still called Botany Bay ... and some lost many more, from sickness or judicial execution.

Masters of the ships that came from Ireland frequently had to hang rebels transported for sedition when their continued defiance of authority led them to attempt mutiny, and only the previous year the William Pitt had landed a sickly band of unhappy wretches suffering from cholera, the arrival of whom had caused consternation throughout the colony.

The governor frowned at the memory but reminded himself that conditions had improved in the time he had been governor. Given a humane ship’s master like Spence, who was assisted by a competent surgeon—both of whom were paid a bonus for every healthy felon they set ashore—then further improvements in the quantity of healthy convicts arriving might confidently be expected.

The home government, alas, still chose the people for transportation without regard for their suitability as future settlers or even for their usefulness as labourers. Indeed, the sole objective appeared to be that of emptying England’s jails of thieves and prostitutes and Ireland’s of her rebels. His predecessors, like himself, had pleaded in vain for some care in selection to be exercised, but successive Colonial Secretaries had turned a deaf ear to such pleas.

They had simply ignored them, as they had ignored even more urgent requests for more reliable troops to be sent out to replace the corrupt and dissolute New South Wales Corps as the colony’s garrison. Pressed for a reason, the war with France was invariably offered to justify refusal ... as, no doubt, it did. Perhaps the Mysore—whose arrival off the Heads had been signalled yesterday evening—would prove to have on board the free settlers Captain Spence had predicted, as well as the usual scurvy sweepings of Newgate and the provincial prisons.

Aware that he could not count on this, William Bligh expelled his breath in a long-drawn sigh of frustration. Thrusting Secretary Windham’s weighty despatches aside, he reached for the latest muster list his own secretary had prepared for him, dark brows furrowed as he studied it.

The population had grown to 7,562 in New South Wales proper, he saw. Of this number, over a thousand were free settlers and emancipist landowners, growing the crops and raising the stock which would render them self-supporting, provided that no disastrous drought—or sudden flooding of the Hawkesbury River—occurred to thwart their efforts and destroy the toil and enterprise of years.

They were the lifeblood of the colony; recognising them as such, he had done all in his power to protect and encourage them, in the teeth of bitter opposition from the military hierarchy and certain civil officials who were bent on enriching themselves at the settlers’ expense.

The New South Wales Corps represented the most intractable obstacle to the future well-being and prosperity of the colony he had been appointed to govern. Since Governor Phillip’s departure fifteen years before, it had earned itself the inglorious title of the ‘Rum Corps’ ... and deservedly, Bligh reflected sourly.

His two immediate predecessors, John Hunter and Philip King—both naval post captains, like himself—had been driven from office by the machinations of the officers of the military garrison and by the dubious activities of one in particular, Captain John Macarthur, now retired from the regiment and the colony’s richest landowner. All had obtained large land grants, with free convict labour to work them, and all had engaged extensively in trade—a trade based mainly on the import and barter of rum. The common soldiers, as well as the convicts and the free and emancipist settlers, had been compelled to use rum as their currency. Wages were paid in rum, purchases made in it, and Macarthur and his brother officers had made personal fortunes from their monopoly of the colony’s liquor imports.

Bligh had been sent out with instructions from the Colonial Office to put a stop to the monopoly and replace the barter system with that based on a stable currency, but ... Impatiently, the governor broke the seals on William Windham’s despatch, swearing under his breath as he glanced through the first of its closely written pages. Windham’s demands were much as Lord Hobart’s had been, his mind registered, if couched in more forthright terms than those normally employed by the previous Colonial Secretary. But it was one thing for a cabinet minister in far-off London to issue instructions to His Majesty’s representative in New South Wales and quite another for that unfortunate representative to implement them.

In heaven’s name, it would take time! Sydney had been in a state of virtual anarchy when he had arrived, and poor King a broken and embittered man, full of complaints concerning the iniquities of the military garrison, but without any advice to offer as to how the situation might be improved or the Rum Corps brought to order. And there was no way short of removing them. Plague take the whole unsoldierly, disloyal bunch ... they were a disgrace to the uniform they wore!