11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

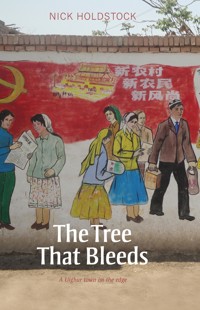

In 1997 a small town in a remote part of China was shaken by violent protests that led to the imposition of martial law. Some said it was a peaceful demonstration that was brutally suppressed by the government; others that it was an act of terrorism. When Nick Holdstock arrived in 2001, the town was still bitterly divided. BACK COVER: 'There is still much that is unclear about what actually happened during that violent week in July 2009. But however terrible its cost - whether it was a massacre of peaceful protestors, an orchestrated episode of violence, or something in between - it was not without precedent.' NICK HOLDSTOCK In 1997 a small town in a remote part of China was shaken by violent protests that led to the imposition of martial law. Some said it was a peaceful demonstration that was brutally suppressed by the government; others that it was an act of terrorism. When Nick Holdstock arrived in 2001, the town was still bitterly divided. The main resentment was between the Uighurs (an ethnic minority in the region) and the Han (the ethnic majority in China). While living in Xinjiang, Holdstock was confronted with the political, economic and religious sources of conflict between these different communities, which would later result in the terrible violence of July 2009, when hundreds died in further riots in the region. The Tree that Bleeds is a book about what happens when people stop believing their government will listen.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

NICK HOLDSTOCK spent three and a half years in China as a VSO teacher. Since returning he has had numerous articles published in publications such as the Edinburgh Review, n+1 and the LondonReview of Books. In March 2010 he went back to China to evaluate how the 2009 riots in Xinjiang have affected people's lives. He lives in Edinburgh and is currently studying for a PhD in English Liter ature. More information can be found at his website:

www.nickholdstock.com.

The Tree that Bleeds

A Uighur Town on the Edge

NICK HOLDSTOCK

Luath Press Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2011

eBook 2012

ISBN: 978-1-906817-64-0

ISBN: 978-1-909912-32-8

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Creative Scotland towards the publication of this book.

The author's right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Some sections of this book appeared in different form in Edinburgh Review, n+1 and the London Review of Books.

© Nick Holdstock

For Magda Boreysza

Table of Contents

Map - People's Republic of China

Map - Major cities in Xinjiang

Acknowledgements

Prologue

The Journey

1

2

3

4

5

6

Autumn

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Winter

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

Spring

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

Summer

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

Afterword

Picture Section

Further Reading

Major cities in Xinjiang

Acknowledgements

THERE ARE MANY people to thank, firstly Jennie Renton for suggesting I approach my publisher. I am also grateful to the Scottish Arts Council for helping fund my trip to Xinjiang in 2010. I would also like to thank John Gittings, former East Asia correspondent of TheGuardian, for his very helpful and encouraging feedback on an early draft of the manuscript.

Thanks to the following for giving advice, rooms to write in, hands to hold, a slap in the face when required: Ryan van Winkle, Benjamin Morris, Dan Gorman, Yasmin Fedda, Duncan Macgregor, Louise Milne and William Watson.

Thank you Mum and Dad.

I WAS LOOKING at the dome of a mosque when I heard the soldiers. The bark of their shouts, the stamp of their feet. I turned and saw rifles, black body armour, a line of blank faces. We were on Erdao qiao, a busy shopping street in Urumqi, where a moment before the main concerns had been the prices of trousers and shirts. But the crowd did not scatter in fear at the sight of these armed men. They parted in a calm, unhurried manner, as if this were a routine sight, almost beneath notice. For a moment the street was quiet but for the soldiers' marching chant. As soon as they passed, the sales men lifted their cries; haggling resumed. But there were more soldiers on the other side of the street, another black crocodile marching through. Policemen stood in twos and threes every hundred metres, outside a bank, a kebab stall, in front of the pedestrian subway. A riot van drove up and stopped at the intersection.

Although this display of force was disconcerting, it wasn't a surprise: nine months before, on 5 July 2009, this street had seen some of the worst violence in China since the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. Urumqi is the capital of Xinjiang, China's largest province. There has been a long history of unrest in the region, between Uighurs (Turkic-speaking Muslims who account for about half the region's 23 million people) and Han Chinese (the ethnic majority in China). The events of July 2009 marked an escalation in the conflict. During the afternoon of 5 July, around 300 Uighur students gathered in the centre of Urumqi. By late afternoon, the crowd had swelled to several thousand; by evening they had become violent. Official figures put the number of dead at 200, with hundreds more injured. News reports on state television showed footage of protesters beating and kicking people on the ground. Video shot by officials at the hospital the previous night showed patients with blood streaming down their heads. Two lay on the fruit barrow that friends had used to transport them. A four-yearold boy lay on a trolley, dazed by his head injury and his pregnant mother's disappearance. He had been clinging to her hand when a bullet hit her.

By the following morning the streets were under the tight control of thousands of riot officers and paramilitary police, who patrolled the main bazaar armed with batons, bamboo poles and slingshots. Burnt cars and shops still smouldered. The streets were marked with blood and broken glass and the occasional odd shoe. Mobile phone services were said to be blocked and internet connections cut.

There were two main explanations for what had caused these riots. On the one hand, a government statement described the protests as 'a pre-empted, organized violent crime' that had been 'instigated and directed from abroad, and carried out by outlaws in the country'. Xinhua, the Chinese state news agency, reported that the unrest 'was masterminded by the World Uighur Congress' led by Rebiya Kadeer, a Uighur businesswoman jailed in China before being released into exile in the US. Wang Lequan, then leader of the Xinjiang Communist Party, said that the incident revealed 'the violent and terrorist nature of the separatist World Uighur Congress'. He said it had been 'a profound lesson in blood'.

He went on to claim that the aim of the protests had been to cause as much destruction and chaos as possible. Although he mentioned a recent protest in the distant southern province of Guangdong, he dismissed this as a potential cause.

But according to the WUC, this incident was the real cause of the protest. They claimed that the clash in Guangdong province was sparked by a man who posted a message on a website claiming six Uighur boys had 'raped two innocent girls'. This false claim was said to have incited a crowd to murder several Uighur migrant workers at a factory in the area. Rebiya Kadeer claimed that the 'authorities' failure to take any meaningful action to punish the [Han] Chinese mob for the brutal murder of Uighurs' was the real cause of the protest.

The WUC's version of the events of 5 July was that several thousand Uighur youths, mostly university students, had peacefully gathered to express their unhappiness with the authorities' handling of the killings in Guangdong. They claimed that the police had responded with tear gas, automatic rifles and armoured vehicles. They alleged that during the crackdown some were shot or beaten to death by Chinese police or even crushed by armoured vehicles.

The WUC also reported widespread violence in the wake of the protests. Their website claimed that Chinese civilians, using clubs, bars, knives and machetes, were killing Uighurs throughout the province: 'they are storming the university dormitories, Uighur residential homes, workplaces and organizations, and massacring children, women and elderly'. They published a list of atrocities – 'a Uighur woman who was carrying a baby in her arms was mutilated along with her infant baby… over one thousand ethnic Han Chinese armed with knives and machetes marched into Xinjiang Medical University and engaged in a mass killing of the Uighurs… two Uighur female students were beheaded; their heads were placed on a stake on the middle of the street' – none of which could be confirmed. This post was later removed.

There is still much that is unclear about what actually happened during that violent week in July 2009. But however terrible its cost – whether it was a massacre of peaceful protestors, an orchestrated episode of violence, or something in between – it was not without precedent. In Xinjiang, there have been many protests which were either 'riots' or 'massacres', depending on who you believe. The largest of these took place on 5 February 1997, in the border town of Yining. This too was perhaps a protest, possibly a riot, maybe even a massacre. There were certainly shootings, injuries, and deaths.

As for what happened, and why, it was hard to say. At the time there was an immediate storm of conflicting accounts, of accusation and counter-claim. The only chance of learning what had happened was to actually go there. And so in 2001, I did. I got a job teaching English. I stayed for a year. I uncovered a story that is still hap p ening now.

But all of this must wait a moment. First, you must arrive.

The Journey

YOUR TRAIN WAITS in Beijing West one thick September night. The air crowds close around, pressing on your head and chest, desperate to transfer a fraction of its heat.

It will be a long journey. Thankfully you'll be travelling in relative luxury: a padded compartment known as a 'soft sleeper'. You slide open its door and find the other three berths already occupied. You heave in your suitcases. You climb into bed. Beijing lapses into haze and you are far from here.

In the morning you wake to yellow valleys honeycombed with caves. Crops crowd the plateaus, anxious not to waste the space. It's a rehearsal for the desert and it is Shanxi. Or Shaanxi. But certainly not here.

You prowl the train in search of food. The restaurant car is full of people eating fatty meat. You find a seat opposite a middle-aged Han couple. The man is wearing a dark blue suit; the woman's pink sweater is embroidered with flowers in silver thread.

They ask where you're from and going. When you say 'England,' they smile. They frown when you say, 'Yining.'

'That is not a good place,' he says. 'It has a lot of trouble,' she adds.

'What kind of trouble?'

He shakes his head, mutters, looks out the window. Then your food arrives. You eat a plate of oily pork. You go back to bed.

When you wake the plain is a vast grey sheet stretched taut between the mountains. It is such a vacant space that every detail seems important: a man walking on his own, without a house or car in sight; ruined buildings; jutting graves; men in lumpen uniforms who salute the train.

Grey slowly shifts to black; sand firms into rock. Then, in place of monochrome, the space is bright with colour. Purple, yellow, red, and orange, mixed like melted ice cream.

Moving on and further westwards. The sun refuses shadow. You pull into the oasis of Turpan, a green island in a wilderness, its shores lapped by grit. You buy a bunch of grapes from a Uighur woman wearing a pink headscarf. They are almost too sweet.

Hours pass, you slip through mountains, speed through a tunnel of rock. You emerge onto to a plain of blades, white and turning, harvesting wind, chopping it into power.

Now, after 2,192km, you are getting close: this is Urumqi, the provincial capital of Xinjiang. From here it is only another 500km. But this is the end of the train.

During the trip your luggage must have bred with the other bags for now there are more than you can carry. It takes two trips to get your bags from the train, and after this, as you stand on the platform, you wonder what you are doing. Why have you come so far, on your own? What if something happens?

But there is no time for worry. You must move your bags. You grunt and heave, to no avail. They are just too heavy. Then you see a man in faded blue jacket and trousers, a flat cap perched on his head. He catches your eye and comes over. He says he will help.

Staggering through the streets, every building that you pass is either half-built or half-collapsed. Dirt is the principal colour. There is a street where the shops only sell engine parts and the pavement is stained with oil. The shops are cubes that flicker, fade, as men spark engine hearts.

You stop to rest. The sky is grey. Two boys approach with a bucket. In it, a kitten is curled.

'How much will you give me?' says one.

'I don't want it,' you say.

'You can't have it,' says the other, who swings the bucket and laughs.

Two more streets and you reach your hotel. The stone floor of the lobby is wet, as is the stairs, the corridors, where men wander in vests.

In your room the man names a price ten times too high. After you threaten to call the room attendant, he settles for five times too much.

The room has two beds. The other bed is occupied by an old Japanese man. He sits in bed reading a book of Go puzzles, smoking cheap cigarettes. His underpants hang on a line at head height. At night the breath whistles out of his mouth like the wind through a crack in a door.

Next morning you go to the bus station. They refuse to sell you a ticket because you don't have a work permit.

'We can't give you a ticket without it,' says a woman in a baggy black uniform.

'But I can't get the permit until I go there.'

'Not my problem.'

'How I am supposed to get there?'

'Don't know.'

'I'll report you.'

She shrugs. 'Go ahead.'

You raise your voice. You plead. You do not get a ticket.

After an hour of angry wandering you find a car willing to take you. You haggle, fix a price, then wait for two hours while the driver tries to find other passengers.

It is midday when you leave. For the first few hours the road is smooth motorway and all but deserted. Exhaustion segues to sleep; potholes bring you back. Straw-coloured hills rise on both sides, at first distant, then slowly converging, until they funnel the road. You wind between them, seeing only their slopes; then abruptly there is a vista. You are on the edge of a lake so blue and vast you cannot see its far shore. The road follows its edge, till mountains loom, and you begin a hairpin descent. The last of the light straggles into the valley below, lingering in jars of honey on shelves by the side of the road.

You assume the crash position as the car hurtles toward lorries. All you get are panic flashes of the countryside: cotton fields, sheep-speckled hills, tough-looking men on horses. It is three days since you left Beijing. You have the feeling that you are on the frontier of another land, that you have come to the end of China.

It is dark when you reach the teachers' college. A small woman you at first mistake for a child lets you into your flat. The strip light shows worn linoleum, concrete floors, a kitchen with a sink on bricks, no pots or any stove. There are no curtains. The toilet is a hole in the floor.

'What do you think?' she squeaks.

You look around, consider your verdict.

'Very nice,' you say.

Now, at last, you have arrived. Welcome to Yining.

1

THE FIRST THING you need to understand about Yining is that it is a border town; Kazakhstan is an hour away. This alone makes it important. Countries that can't maintain their borders don't stay countries for long.

Yining is located in the north-west corner of Xinjiang ('new land'), China's westernmost province. At 1,650,000km2 (about the size of France, Germany and Italy put together), it is also its largest.

Xinjiang is defined by mountains: the Himalayas and Pamirs to the south, the Altai mountains to the north. The Tian Shan ('Heavenly Mountains') slice from west to east, chopping the province in two. And the mountains are not just border markers. The Himalayas and Pamirs steal the moisture from the tropical air that comes up from the Indian Ocean. Little rain falls on the south of the province; the result is the Taklamakan Desert, a vast area of sand and gravel that may contain more oil and gas than Saudi Arabia.

But the mountains are merciful: there's enough snow and glacier melt to irrigate a series of oases that stretch along the desert's edges. These are the towns of the Silk Routes, the old trade arteries between Europe and Asia.

The second thing you need to understand about Xinjiang is that many of its people aren't Chinese.

2

OF COURSE' IN ONE sense all the people in Xinjiang are Chinese. They are all part of the Chinese nation. So in what sense are many of them not Chinese?

The difficulty lies in the way that we use the term 'Chinese'. Usually, when we say a person is Chinese it means one of two things: their nationality or their ethnicity. It's easy to conflate the two because China has a clear majority ethnic group, the Han, who make up about 90 per cent of the population. Most of our knowledge about the culture of China – its food, films, art, traditions and language – relates to this group. So when we say that something or someone is Chinese, that thing or person is usually from China and of Han ethnicity. But in Xinjiang there are 12 other ethnic groups that together make up around half of the population; they are thus both Chinese and not Chinese.

The Uighurs (pronounced 'wee-gers') are the largest of these groups, after whom the province is named: officially, it is the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. The Uighurs are a Turkic people – they belong to the same group of peoples who began in Central Asia and eventually spread as far as Turkey. Uighurs speak a Turkic language (closely related to Uzbek) which is written using a modified Arabic script. The majority of Uighurs are Sunni Muslims, though there are considerable differences between religious practices in the north and south of the province, with the latter tending to be more orthodox.

The second-largest group are the Hui, who are also Sunni Muslims. The Hui are descended from Arab and Iranian merchants who came to China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907AD). Unlike the Uighurs, who are concentrated in Xinjiang, the Hui are distributed throughout the country; almost every major city in China has a Hui community. Unlike the Uighurs, the Hui no longer possess their own language and in appearance are often indistinguishable from the Han.

But despite the large numbers of Hui and Uighur in Xinjiang, Yining is primarily associated with neither. Yining is the capital of the Yili Kazakh Autonomous Region (another of those catchy titles the Chinese government excels at). Over a million Kazakhs live in the north-west of Xinjiang, many of whom are semi-nomadic herders. Kazakhs first came to the Yili valley in the 19th century, seeking refuge from Russian expansion.

Yining is thus the centre of a Kazakh region within a Uighur province of a (Han) Chinese country. I wish that I could say that all these different ethnic groups exist in joyous harmony. But there are problems, not least of which is history.

3

THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT'S position on the history of Xinjiang is admirably clear:

One thing cannot be denied. Xinjiang has always been a part of China. Since the time of its origins, our great motherland has always been a multi-ethnic nation.

The position of some Uighur groups is similarly clear.

One thing cannot be denied. Xinjiang has never been a part ofChina. Only in recent years have we become a Chinese colony.

Their different views of the events of 1949 – the year that the People's Republic of China was founded – are equally transparent.

1949 was the greatest year in our country's history. It was a year of hope and joy: a year of Liberation.

1949 was the worst year in our country's history. It was a year ofdeath and fear: a year of occupation.

As are their views on the relations between the different ethnic groups.

Xinjiang is a good example of how the problems of a very different mix of ethnic groups have been solved. They have been united into one big family. The Han nationality has always kept a higher level of development, so many of the other peoples have learned a lot from the Han mode of production and way of life. The Han have self lessly regarded this kind of assistance as their responsibility. They are the big brother of the family. They have helped to develop a once backward region. Life today in Xinjiang is better than ever before!

The Han have been sucking our blood for decades. They only knowhow to take. Our oil, minerals and gas, our homes and our freedom.We are homeless in our homeland, we are orphans in our motherland, we are slaves in our fatherland. Our people are starving in theworst conditions of human misery.

And on those who argue for Xinjiang's independence.

Although national and ethnic unity is the common wish and desire of every person in Xinjiang, we must also admit that ever since Liberation, a small number of separatists, backed by hostile foreign forces, have been determined to sabotage ethnic unity and the integrity of the motherland. These counter-revolutionary terrorists often cloak their separatist slogans in the guise of religion. But these people will never be allowed to break up our glorious motherland.

But we have never given up. An independence movement hasexisted since the first day of the Chinese occupation. The Uighurswill never stop struggling against the fascist Chinese regime. We willcontinue to resist this oppression. And one day we shall be free.

But this is not history. This is propaganda. On one side, the Chinese Communist Party; on the other, pro-independence Uighur groups. The latter argue that 'Xinjiang' (a label they reject) should instead be recognised as East Turkestan, a place that has always been the homeland of Uighurs and certainly separate from China. It is tempting to draw a parallel with Tibet; in both cases, the Han Chinese can be viewed as invaders.

However, even a brief study of Tibet's history suggests a more complicated relationship, one where the Han fade in and out, sometimes playing the aggressors, at other times, absent and fragmented neigh bours, who were themselves invaded by the Tibetans on several occasions.

The history of Xinjiang is similarly complex. The idea of the region as a single unified area dates back no further than the middle of the 18th century. For most of its history, the region has not been united under any one authority.

There has certainly been a Han Chinese presence throughout much of the region's history. The first recorded contact was in the 1st century BC, when the Han emperor sent an envoy in the hope of uniting its tribes against the invading Huns. The Han court later established an administrative centre in Xinjiang between 73 and 97AD. Xinjiang remained under their control until the 5th century, when it was conquered by Turkic tribes. During the Tang Dynasty it was briefly recovered, but after the demise of the dynasty it remained out of Chinese control until 1750, when it was taken by the Qing (who were themselves invaders). It was they who renamed the region 'Xinjiang'. But their presence remained a marginal one, mostly confined to soldiers, officials and prisoners. Many Chinese were said to view the region as 'a kind of purgatory'.

The huge distances between Xinjiang and the centres of imperial power (before the introduction of motorised transport, it took over

100 days to get to Beijing) made it hard for the authorities to main tain control. A succession of riots and uprisings took place through out the 19th and early 20th centuries, which led the region to acquire a reputation for being China's 'most rebellious territory'. Only since 1949 has the region been fully integrated into the rest of China.So in the last 2,000 years Chinese control in Xinjiang has been more the exception than the rule: Xinjiang has not always been a part of China. But does that mean it has been a Uighur nation?

4

All historical rights are invalid against the rights of the stronger.

ALEXANDER TILLE, Volksdienst

IN 1981' A WOMAN'S BODY was found at Loulan, deep within the Taklamakan Desert. She had long golden hair, a European nose, and was very, very old. But the dry sands had treated her well; she scarcely looked her age. You wouldn't have taken her for more than 1,000, though in actual fact she was at least 3,000 years old, perhaps even 6,000.

They found other bodies, some with brown or reddish hair. Who these people were has been debated ever since; even their age is contested. At first, radiocarbon dating suggested they were over 6,000 years old but this finding is likely to have been contaminated by radiation from nuclear testing in the area. More conservative estimates place their age at approximately 3,000 years.

The question of these mummies' identity has become politicised. If they were Uighur (many of whom have light brown or, occasionally, reddish hair) it would provide strong support for the idea that Xinjiang was home to Uighurs long before the Han arrived. This has led to claims that Uighurs have a 6,000-year history in Xinjiang.

The problem with this is that the mummies are no closer to Turkic peoples than they are to Han Chinese. Elizabeth Barber, an expert on prehistoric textiles, argues that the bodies and facial forms associated with Turks and Mongols don't appear in the region until a thousand years after the mummies lived. According to her, the more likely explanation is that these people were originally migrants from central Europe. Any similarities between some Uighurs and these mummies are thus probably a legacy of old intermarriages.

So this is one reason why Xinjiang has not been a purely Uighur domain for all time. The other is that the earliest Uighur kingdom was in Mongolia.

5

THE UIGHURS RULED most of Mongolia between 744 and 840AD. Most of the people followed Manichaeism, an early Christian sect based around the distinction between Light (representing the spirit) and Darkness (representing the flesh). Adherence to these beliefs is said to have transformed 'a country of barbarous customs, full of the fumes of blood, into a land where people live on vegetables; from a land of killing to a land where good deeds are fostered'.

One of these 'good deeds' was helping out the Tang, the Chinese rulers at the time, who were struggling with an internal revolt. The Uighur kingdom began to disintegrate at the start of the 9th century, due to war with the Kirghiz, who invaded in 840AD.

The Uighurs fled and established a new, predominantly Buddhist kingdom around the eastern oasis of Turpan, which endured until the Mongol invasion in the 13th century. During this period, the rest of the region was controlled by other Turkic peoples, most of whom were Muslim. At the time, the term 'Uighur' was used to denote someone who was not Muslim. After the majority of Uighurs had converted to Islam in the 15th century, the term fell out of usage. However, it was not so much a people who disappeared but an identity.

It was not until the 1920s (after Stalin started a craze for ethnic labelling) that the term came back into use. There is some debate over who first reintroduced the term, but it seems clear that by the start of the 1930s, 'Uighur' had acquired its current meaning: a Muslim oasis-dweller.

The term 'Uighur' has thus been used to define populations according to different ethnic and religious criteria. The present notion of 'Uighur' is thus as much a modern creation as 'Xinjiang' itself. The messy truth appears to be that Xinjiang was little more a Uighur kingdom than a Chinese one. The history of the region is rather that of many different peoples, and shifting bases of power.

But in a sense, whether the Chinese government or Uighur nationalists are right isn't important. What matters is that both believe themselves to be. Thus we have two groups of mutually exclusive views, both laying claim to the same territory; both with too much invested in their particular historical narratives. Which brings us back to the riots.

6

THE FIRST AND greatest problem with the events of February 1997 is that most accounts are from people who weren't present, or from those who were but are far from impartial. Foreign reporters were denied permission to visit the area, and at the time official comment was limited to revealing statements such as, 'There was a protest. It was illegal. Illegal protests are curbed'.

Most foreign journalists chose to portray it as a political protest. An Associated Press report described the events as 'a Muslim march demanding independence'; Reuters described it as 'a separatist riot'; CNN called it a 'protest against Beijing rule'. But there were plenty of alternative explanations. The East Turkestan Information Centre (ETIC) described it as 'a peaceful demonstration demanding respect for human rights'. A number of official Chinese sources later claimed that it was nothing more than random violence, the work of drug addicts, thieves and other 'social garbage'.

Despite their differences, the various sources generally agree on the following: approximately 1,000 young Uighur men marched through the town shouting slogans. The marchers clashed with the police and there were numerous injuries and casualties. Afterwards there were multiple arrests and executions.

It is the details that are disputed. How many were killed? Estimates range from none to 1,000. Who started the violence? The police – who were accused of firing into the crowd – or the protesters? They were accused (as they would be 12 years later, in Urumqi) of looting and damaging property, of attacking Han Chinese.

The Xinjiang regional government claimed the protests had been orchestrated by 'hostile foreign forces' determined to over throw the government (again, a claim that was repeated in July 2009). Some said the trouble started when police arrested some religious students; others that the protests were triggered by the executions of 30 Uighurs the previous week.

How many were arrested? 100? 500? 1,000? What happened to them? Were they displayed naked in city squares and publicly tortured, as was later claimed by some overseas Uighur groups?

These were the questions I hoped to answer.

Autumn

7

FOR ALL ITS REMOTENESS, Yining is a place that people have heard of. It has been in the Lonely Planet guide since the first edition.

In Yining you won't know whether to laugh or cry. Nothing seems to work and half the population seems permanently drunk.

The guide had mellowed slightly by its fifth edition.

Yining is a grubby place with a few remnants of fading Russian architecture.

Despite these ringing endorsements, there were already ten other foreigners in Yining when I arrived. Eleanor was the first I met. She was tall, friendly and from Derbyshire, and had already been teaching in the college for two years. She introduced me to some people.

* * *

The bus crawled down Liberation Road, stopping, starting, pres enting tableaux: nicotine-coloured apartments; muffled road sweepers waking dust; a donkey pulling a cart of red apples; a crowd gath ered round an argument, one man pointing at a crushed bicycle, another leaning against a taxi, slowly shaking his head.

We veered right at a roundabout topped by a stone eagle. A soldier stood outside a concrete gate, a rifle by his side. More turns later we arrived at the town square, which was paved in pink and white tiles.

Two Uighur men were waiting for us, one very tall, one short, both with thin moustaches. The smaller smiled, and said in English, 'Welcome to Ghulja. I'm Murat.'

'Does he mean Yining?' I whispered to Eleanor, but Murat nonetheless heard. He snorted. 'That's what the Chinese call it. We say 'Ghulja'. It means a wild male sheep.'

Ismail was the taller of the two. He and Murat ran an English course in a local school. We had lunch in a restaurant called King of Kebabs. A fat man sat outside threading lumps of meat onto skewers. A cauldron of rice and carrots steamed next to him. When he saw us he stood and boomed a greeting. He shook hands with Murat, Ismail and me, nodded to Eleanor.

Inside was dim and noisy with the sounds of eating. Ismail gestured for us to sit then said, 'This is a good place, very clean. You know, Uighur people are Muslims. We shouldn't smoke or drink. What would you like to eat? Have you had polo? It is traditional Uighur food.'

Polo turned out to be the rice and carrot dish I'd seen steaming outside. In addition, there were soft chunks of mutton and a tomato and onion salad dressed in dark vinegar.

'Is it good?'

'Very.'

Ismail grinned and said, 'You must stay for a long time!' After that we ate in silence until Murat said, 'Many Han people make a noise when they eat.'

Ismail chimed in, 'That's just them speaking!'

I kept eating, quietly, a little shocked by the vehemence of their dislike. It also surprised me that they were saying such things to someone they had only just met.

After lunch we strolled through the square. Huge propaganda posters towered overhead. A composite photo loomed above, showing three generations of Chinese leaders: Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin (the then-current leader). Next to it was a 20-foot poster showing all 57 ethnic groups in China. They were smiling and wearing brightly coloured costumes. They seemed about to launch into song.

There was a sense of transition on crossing the square. The bright cubes of the Han shops, their handbags, shoes and machine parts, quickly faded into market stalls – to scarves, carpets, glassware, packs of henna, crystal sugar, dried grapes, black tea and other products more reminiscent of a Central Asian bazaar. Bare heads were replaced by a hundred hats, by homburgs, trilbies, flat caps, pork pies, baseball caps and most of all, a boxy, stiffened skullcap called a doppa.

Murat turned and whispered, 'Don't tell anyone, but I MUST go to the toilet.'

'OK. Isn't that one, over there?'

'Yes, but I must go home.'

As we watched him scamper off, Ismail cleared his throat.

'It takes him a long time. He has this problem. With his…'

He didn't know the word. Eventually we settled on 'kidney'. Eleanor chose this moment to mention that she thought our phones were bugged. She said that sometimes she heard noises from the other end, and that there had been some dubious coincidences, like going to make a complaint about something and finding that the person in question had already taken steps to nullify her criticisms. At the time I thought she was being paranoid. After a few weeks in Yining, I was not so sure.

When Murat returned he looked pleased with himself, as if he had performed some difficult task well. He suggested looking round the market. As we drew near the entrance – a large faux-Islamic gate – three men selling pictures of Mecca started shouting at us.

'What are they saying?'

Murat laughed. 'They are saying 'Hello Russians!'

There has been a long history of Russian involvement in Yining: Russia occupied the valley from 1871–81; after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the Soviets were granted special trading rights in the area and had a consulate in the town. Following the Sino-Soviet pact of 1924, Russian involvement in the province increased to the point where 80 per cent of the region's trade was with Russia. Sheng Shicai – the warlord ruler of the province from 1934–44 – relied heavily on Soviet military aid. Russia was forced to with draw from the province in 1943, after Sheng Shicai shifted his allegiance to the Nationalists. Following their withdrawal, inflation rose and trade virtually stopped. But they were soon presented with an opportunity to re-establish their influence when a revolt broke out among the Kazakhs, who had been especially dependent on trade with Russia. Direct Soviet military aid on the side of the rebels led to the capture of Yining in 1944, and the founding of the East Turkestan Republic (ETR). The Russian presence in Yining remained strong until the Communists took power in 1949. Relations between Russia and China worsened throughout the 1950s, culminating in the Sino-Soviet rift of 1960 and the eradication of Soviet influence from the region.

Today there are few traces of the city's Russian past. Apart from the Russian consulate, which is now a restaurant, there are only a few scattered buildings, some within the teachers' college. Only a handful of Russians still live in the city, running a bakery that makes perfect cakes.

So given that most foreigners in Yining had previously been Russian, it was logical that Eleanor and I should be Russian too. I didn't mind; it made a change from everyone thinking I was American.

The market was dim and busy, full of rows of traders selling leather jackets, wraps and hats, doppas, stiff suits, thick jumpers, sensible shoes, armoured trench coats, various fur things. The traders whistled at me, trying to get my attention. Ismail and Murat shook hands with many of them. I asked how they knew them.

'Ismail and I used to do business. We used to sell leather.'

'Why did you stop?'

'Things are difficult now. Business is bad.'

Ismail sighed. 'Many people don't have jobs. Especially Uighur people. Maybe 80 per cent are unemployed now.'

'Why's that?'

Ismail looked at the floor while Murat said, 'In this city, there are some problems. Maybe you don't know. It is difficult.' He coughed then said, 'Please excuse us. We must go and pray.'

It was their third prayer of the day. Eleanor and I drifted round the back streets while they went to the mosque. A group of kids took time from booting a ball around to giggle at us; the braver ones ventured a hello. Two men sat playing chess, their stillness broken by sudden aggression as one slammed a bishop down. Peace returned, and then was broken. The sky showed no sign of being bored with blue.

8

NEXT MORNING THE telephone woke me.

'Hello, Nick?' 'Yes?' 'This is Miss Cai.' Who? 'I am waiban.'That at least I understood. The waiban ('foreign officer') is the person responsible for the safety and welfare of foreigners. I decided she must have been the child-like woman who let me into my flat when I arrived.

'Please come to my office now. I have something to tell you.'

'All right. Er, where's your office?'

'By the gate. On the second floor.'

I went out, got lost, asked for directions, was ignored, tried again, and was finally helped by a boy who took hold of my sleeve and did not let go till we were outside a long, two-storey Russian building. I went inside and climbed to the second floor, wandered down a hallway, tried several doors, till I was looking at a small woman in maroon who seemed to leap up when she saw me while still remaining seated.

'Nick! Hello! Come in! Come in!'

She could not have sounded more delighted: as if we were about to embark on some long-promised picnic.

She began by apologising for the state of my flat, saying that she had wanted to buy some cleaning things but had been unable to because the president of the college was having kidney stones removed. She paused, looked suitably grave; I dutifully asked how he was.

'Better! Much better! Now he can sign the purchase order.'

'That's good,' I said, and thought of asking for curtains, maybe even some bowls.

'And what about your health?' she said, in a tone of pure solicitude.

'Fine, thanks.'

'Good! And your family?'

'Very well.'

These pleasantries went on for a while. Not until things were utterly cosy did she get to her point.

'Nick, the president of our college has asked me to tell you some things. They are very important. As you know, Yining is a border town. This is a safe place, but you must still be careful. There are some bad people who want to cause trouble.'

'What kind of trouble?'

'Some people try to use religion as an excuse for crime. They want to separate from China. They are very bad.'

She frowned at their badness.

'So you must be careful. Your safety is important to us.'

'Thank you.'

'Of course! There are some other things. No one can stay in your house except you or a relative.'

'Why not?'

'It's against the rules. Also, you shouldn't stay out at night.'

'Why?'

'Sometimes there are bad people outside. Another thing is about religion. In our country, everyone has freedom of religious belief. But it is against our law to try to force others to believe something. Some foreigners came to China in the past to do this.'

'Don't worry, I don't believe in any religion.'

'Really?'

She looked sceptical.

'Not all foreigners believe in God.'

This was clearly news to her.

'You don't believe in anything?'

'Nothing.'

'Oh, well, good!' She backtracked to disbelief.

'But why don't you believe?'

'I don't know. Maybe I believe in science instead.'

'Good, good! Oh, there's one more thing. You mustn't go over the bridge.'

'Which bridge?'

'The one over the Yili river.'

'Why not?'

'That's a different county. It's closed at the moment. You mustn't cross the river.'

9

THE SUN SHONE DOWN reprovingly as I cycled over the bridge. The river that ran beneath was swollen but indifferent. Only the mountains encouraged me; they spread their snowy arms. I felt the special joy that comes from breaking rules. I wasn't sure how far I'd get but this didn't matter since I had no idea where I was going.

The road was lined with silver poplars. I dragged the stick of my gaze along their trunks as I pedalled. Tree, tree, tree, what? Some thing tent-like, white and circular with a horse tethered outside. A yurt, perhaps.

Gradually the heat increased, and with it, a rich smell, as of spice but mixed with engine oil. I passed two other cyclists, their old frames festooned with honking geese, at least 20 on each bike. The cyclists were Uighur, which gave me a chance to practice the one word of their language I knew.

'Yakshimsis,' I said, and when they understood, and said hello back, I was unjustifiably smug.

Herds of sheep grazed next to streams; their minders slept or fished. I kept expecting to be stopped but no one seemed anything other than curious, not even the soldiers smoking in a copse of birch. I stopped to watch two Uighur kids trying to catch fish in a leaky jam jar. I popped my gum out, stuck it over the hole, and then we all grinned.

'Where are you from?' said one of the kids in Chinese; he was wearing a blue baseball cap. When I told him, he started laughing uncontrollably. His friend did not laugh and in fact looked very serious. 'There are many wolves,' he said, and refused to believe otherwise.

I cycled on till I was almost killed by a wire strung across the road at head height. Ten feet further on the road was just rough stones. I took the hint and turned onto a small track. The fields were midway through harvest, their contents still their own. Fodder, wheat, and corn were stacked in mounds awaiting transport. I stopped to take a photo of a row of red chillies hanging out to dry.

A family sat in the next field, cooking on a fire. They laughed to see me take a picture of something so ordinary; then they called me over. Three generations were present: several matrons in their 40s; two young girls scampering round; a septuagenarian matriarch. The girls giggled when I said hello, then were hushed by their grand mother. She offered me a seat in their shelter, a three-sided structure made from lashed branches with a rush roof and dirt floor. Most of the space was taken up by a large bed of rugs laid upon thick planks. A shelf ran along two of the walls. On it there were some bowls, a toothbrush, a pile of chopsticks, some string, a chopper, and a very large bag of white powder.

I didn't think they were Uighur, and they certainly weren't Han or Hui. I tried the only other option that I knew.

'Are you Kazakh?' I asked in Chinese.

One of the girls replied, 'No, we're Xibo.'

'Xibo?'

'Yes, there aren't many of us. Most are in Heilongjiang.'

Heilongjiang is a province in the far north-east of China. How did the Xibo end up on the other side of the country?

In some ways the story is similar to that of the Han Chinese in the 1950s, only bloodier. At the start of the 18th century, the Qing government (who were ethnically Manchu, not Han) were in the process of conquering the area, in one sense 'making' Xinjiang. Their campaign was halted in the northern part of Xinjiang (what is sometimes referred to as Jungaria, an area that also incorporates western Mongolia and eastern Kazakhstan) by the Junggar Mongols, who inflicted a major defeat on them. This major loss of face and life prompted Emperor Kangxi to dispatch Zuo Zongtang, one of his best generals. He adopted a slow but sure approach: his soldiers planted crops, waited to harvest them and then moved on, thus ensuring the health of the troops. It took them three years to reach the Junggar plateau, whereupon they exterminated the Junggar Mongols. Afterwards the region was so depopulated that the Emperor had to send 1,000 Xibo officers and soldiers, who took along more than twice that number of family members. The Xibo, along with the remnants of the Manchu army, can be credited with making the area fit for cultivation, mainly through the development and use of irrigation. Today, there are around 35,000 Xibo in the area, most of whom work in agriculture. The other noteworthy thing about the Xibo is that they use the Manchu written script, which is written vertically (unlike modern Chinese), looks like a comb with fluffy teeth, and is still used on street signs in the area.

The sun climbed to its zenith as we sat and chatted. When I stood up to leave, they told me to sit down: lunch was almost ready. I sat and watched the women shred a pile of peppers, tomatoes and chillies to go with a tower of nan bread. Men emerged from the surrounding fields; by the time we ate we were 12.

The salad was moist and delicious, if a little salty. One of the older women asked if the food was all right.

'It's great.'

'Don't be so polite! There's not enough salt.'

She scattered some over the vegetables. For a few minutes we ate in silence. Then one of the men said, 'It needs a little more.'

There were grunts of approval as he threw a handful on. My kidneys began to whine. Hope appeared in the form of steaming tea, poured into bowls with milk. A tub of white powder was passed to me. Taking it for sugar, I put a large pinch in, then drank. Salt. It was salt. My kidneys gave up.

The Xibo's liberal use of salt allows them to consume more of staple foods such as rice or bread, which helps when there isn't much else to eat. Unsurprisingly there is a high incidence of heart disease and kidney failure among the Xibo.

By now I was gasping. I made my excuses and took a photo of the family that I promised to send. There was some discussion about whether they should write their address in Chinese or Xibo; they eventually agreed on both.

I shook the men's hands, thanked the women, pedalled towards water.

10

BEFORE I WENT TO Yining, I taught in a college in Hunan, a province in southern China. Hunan is quintessential rice-field China: a wet expanse of squares that flash a brilliant green in spring. When one of my students heard I was leaving he said, 'How wonderful! Xinjiang is a good place. You know, our government wants to develop the west. It is a necessary.'

I corrected his grammar, then asked why.

'Because Xinjiang is so… backward. It is very poor. It–'

He was interrupted by another boy. 'Yes, but the Xinjiang girl is very beautiful! And the people there are very good at dancing and singing.'

I asked if they had ever been.

'No, but I want to,' said the first.

'And I've seen it on TV,' said the other.

Most expressed similar sentiments on hearing I was going to Xinjiang. No one I knew had ever been which didn't stop the refrain of 'singing/dancing/beautiful'. It was a crude stereotype but one for which I couldn't blame them. Their newspapers and maga zines were full of smiling, dancing, singing Uighurs in shiny, happy costumes, the girls all slight and coy, the men silent and strong. There was nothing to compete with these images: Xinjiang was a three-day train ride away and there were no Uighurs in town. I comf orted myself with the thought that at least my students in Yining would be better informed.

11

Xinjiang is famous for her delightful scenes: bright lakes, sweet melons and most of all the Uighurs Dance. The Uighurs are an ethnic group who are good at singing and dancing. It's their practice to sing and dance in gala dress when they meet new friends. The Uighurs Dance is a symbol of their colourful life.

Yang Haimei

THIS GIRL HAD BEEN living in Yining for three years when she wrote this. She, like the majority of my students, was 20, female and Han. Most of them came from new towns in the north of Xinjiang, places like Shihezi, Kuytun and Karamai.

Before 1949, there were around 20,000 Han in the region, less than five per cent of the population. The succeeding years wit n e s sed a demographic explosion as the government encouraged Han from the more populated provinces to resettle in the region. Today there are said to be about six million Han in Xinjiang, about 45 per cent of the population (though these figures are most likely an underestimate, as the government probably doesn't wish to publicise the scale of Han immigration).

At least a third of these are part of the Xinjiang Production & Construction Corps (XPCC). The XPCC was created in the early 1950s as a way to utilise soldiers from the surrendered Nationalist army. Between 1952 and 1954, 170,000 soldiers were ordered to retire from the People's Liberation Army and then incorporated into the newly founded XPCC. By 1961, a third of the region's arable land was being cultivated on state farms. From 1963 to 1966, 100,000 people were sent from Shanghai alone. Since then successive waves of migration have swelled the ranks of the XPCC, which today stands at around 2.5 million.

The XPCC is a unique institution in China, in that it is administered independently from the Xinjiang provincial government. It has its own police force, courts, agricultural and industrial enterprises, as well as its own large network of labour camps and prisons. Its main unit of production is the state farm or bingtuan. The bingtuans have had the dual function of developing the region's economy and in quelling unrest; in one of its marching songs the XPCC describes itself as 'an army with no uniforms'.

It is not just the agricultural population that has swelled; the urban population has also increased rapidly in the last few decades: Kuytun grew from a small village to a city of 50,000 by 1985; Urumqi went from 80,000 in 1949 to 850,000 in 1981. In many of these newer northern cities, the Han Chinese became the majority, often living in separate, ethnically defined communities.

So in one way it wasn't surprising that many of my Han students knew little more about Uighurs than their Hunanese counterparts. They had grown up in places that were predominantly Han. But Yining was different. In 2001, the Kazakhs and Uighurs still out numbered the Han. But after three years in this mixed environment, my Han students had progressed no further than the 'singing/ dancing' stereotype.

It was puzzling, as was the fact that of the roughly 200 students in the English department, all but ten were Han. When I asked other teachers why there were so few Uighur or Kazakh students, I was told that Uighur and Kazakh students weren't interested in learning English. At the time this seemed a little strange, as the Uighur and Kazakh students seemed interested in all the other subjects. But several things prevented me from dwelling on these questions. The state of my flat was one – I still had no stove, curtains or pans. Another was all the strange people I was meeting.

12

OF ALL THE PEOPLE I met in China, both in Hunan and Xinjiang, the oddest were invariably the other foreigners. Whether their eccentricity had pre-dated China, or was something they had developed postarrival was impossible to say. At first I wasn't too keen on having other foreigners around; it seemed too easy for us to slip into some cosy expat clique. And when I heard there would be ten of them in Yining, I had second thoughts about going. But I shouldn't have worried: it proved easy to muster a clinical interest in them.

I was about to go to bed when there was a knock at the door. I opened the door and a man strode in, tall with brown hair, wearing a check shirt. His left arm was in a sling.