13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

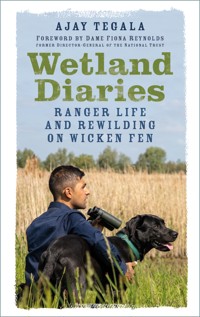

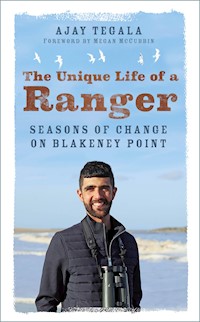

Few people have had the privilege of living on an isolated nature reserve of international importance, their every move judged by countless critics. Young ranger Ajay Tegala, embarking on his placement at Blakeney Point aged just nineteen, would have to stand firm in the face of many challenges to protect the wildlife of one of Britain's prime nature sites. In over 120 years, only a select few rangers have devoted their heart and soul to the wildlife of Norfolk's Blakeney Point. Watching and learning from his predecessors, Ajay faced head-on the challenges of the elements, predators and an ever-interested public. From the excitement of monitoring the growing grey seal population, to the struggles of trying to safeguard nesting birds from a plethora of threats, in The Unique Life of a Ranger, Ajay shares the many emotions of life on the edge of land and sea with honesty and affection.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Cover image © Dan Sunderland

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Ajay Tegala, 2022

The right of Ajay Tegala to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9136 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Dedicated to

Bob Pinchen (1865–1943)

Professor Francis Oliver (1864–1951)

Billy Eales (1883–1939)

Ted Eales (1918–92)

Reginald Gaze (1894–1974)

Joe Reed

Graham and Marilyn Lubbock who all dedicated many years to the protection of Blakeney Point.

And everyone who has helped protect the Point in any way – in particular, those I have had the pleasure of working alongside, and family and friends to whom I have never managed to adequately explain what it is like to live and work on Blakeney Point.

In memory of

Simon Aspinall, John Bean, Ray Greaves, Ben Collen, Martin Woodcock, Steve Trudgill and my Grandad: Peter Haywood

Young grey seal pup. (Ajay Tegala)

This medieval ship emblem has appeared on several Blakeney Point publications.

Contents

About the Author

Foreword by Megan McCubbin

Acknowledgements

Preface: Riding a Tide

Introduction: Reaching a Point

Part 1: Beginnings – A Year on the Coast

1 Minding the Gap

2 The Freshes

3 Back and Forth

4 Holiday Season

5 Quieter Times

6 Winter Wonder

7 Spring Splendour

8 Rare Birds and Impressionable Youngsters

9 Strange Goings-on

10 Farewell for Now

Part 2: Point-Based – A Season on the Shoreline

1 April: Anticipation

2 May: Migration

3 June: Hatching

4 July: Fledging

5 August: Autumn Arrives

6 September and Beyond

Part 3: Seabird and Seal Seasons – A Dream Come True

1 Preparation

2 Nesting

3 Necessary Evil

4 Storm Surge

5 Year of the Fox

6 Year of the Rat

7 Year of the Large Gulls

8 Blubber on the Beach

9 Research and Discovery

10 Tales of the Unexpected

11 Treasured Memories and Changing Faces

Bibliography

Appendix 1: List of Blakeney Point’s Breeding Bird Species

Appendix 2: List of Blakeney Point’s Notable Wardens

Appendix 3: List of Ajay Tegala’s Media Appearances

About the Author

AS A WILDLIFE PRESENTER, Ajay Tegala shares his passion for the natural world. His credits include Springwatch and Inside the Bat Cave (both BBC Two). As a countryside ranger, Ajay is grounded in the world of nature conservation. At the age of 15, he decided to become a conservationist after a week’s work experience at Wicken Fen.

Ajay grew up in East Anglia and went on to complete a degree in Environmental Conservation and Countryside Management at Nottingham Trent University, alongside volunteering on the north Norfolk coast at Blakeney Point. He went on to become the Point’s full-time ranger, protecting shorebirds and seals as well as inspiring countless visitors.

www.ajaytegala.co.uk

Foreword by Megan McCubbin

THE BRITISH COASTLINE IS a landscape characterised by drama and intrigue. The land lies exposed to the blanket of waves that, gentle or powerful, continue to re-shape its features. It’s here that a very select, very special group of wildlife make their home. The intertidal and coastal habitats are some of the most inhospitable in the world as species must be able to thrive in the ever-changing hot, cold, wet, dry and salty environment it presents. Visiting these environments is enchanting and a wonderful day out – but it’s another thing entirely to dedicate your life to understanding its patterns and to protect its wildlife.

Ajay Tegala has dedicated much of his time working as a ranger on an isolated, internationally important nature reserve: Blakeney Point, where Norfolk meets the North Sea. He lived in a former lifeboat station at the end of a 4-mile shingle spit and worked with a small team of colleagues and dedicated volunteers to protect vulnerable ground-nesting birds during their breeding season, including rare terns migrating from Africa.

Ajay writes so eloquently, bringing to life the stories that have made him the passionate naturalist he is today; from his first visit to Blakeney Point to the many, many sleepless nights safeguarding precious terns from a whole host of potential dangers. With extracts from his diary, you feel as though you are alongside him learning what it takes to be a ranger. You feel the ups and downs as he encounters new species and watches the chicks he so devotedly protected successfully take their first flight.

This intimate and unique window into a small patch of the British coastline is beautifully written. For conservation, it’s important to know an area well but to live and breathe it, each and every day throughout the seasons, is something remarkable. Ajay’s passion bursts through the pages. And, if you’re anything like me, you’re left with the urge to grab your walking boots and head out to your local patch so that you can get to know it that little bit more.

Megan McCubbin

Acknowledgements

FOR THEIR SUPPORT DURING my Blakeney days, thanks to Graham and Marilyn Lubbock, Eddie Stubbings and Bee Büche, Chris Everitt, Dave Wood, John Sizer, Richard Porter, Richard Berridge, Barrie Slegg, Paul Nichols and Sarah Johnson, Mike Reed, Joe Reed, Jason Bean, Graham Bean, the late John Bean, Jim and Jane Temple, Bernard Bishop, Keith Miller, the late Ray Greaves, Simon Garnier, Desmond McCarthy, Sally Chandler, James McCallum, Joe Cockram, Pat and Alan Evans, Andrew and Kay Clarke, Iain Wolfe, Al Davies, Andy Stoddart, George Baldock and Alex Green, Victoria Egan, Neil Lawton, Jason Pegden, Lucas Ward, Nick Bell, Stuart Warrington, Matt Twydell, Godfrey and Judy Sayers, Bill Landells, Martin Perrow, Brent and Brigid Pope, Alison Charles, Richard Timson, Simon Gresham, Greg Cooper, Terry Sands, Stuart Banks, Josh Herron, David Bullock, the late Josh Barber, Harry Mitchell, Tony Martin, Faith Hamilton, Sabrina Fenn, Mary Goddard, Anne Casey, Steve Prowse, Carl Brooker, Luke Wilkinson, Ryan Doggart and Wynona Legg, Val MacFall, Leighton Newman and many other locals, volunteers, colleagues and conservationists who I have had the pleasure of working with and learning from. Huge thanks, of course, to my wonderful family, too.

Special thanks to the National Trust, who have been caring for Blakeney Point since 1912 and have employed me in various roles since 2010. Thanks also to University College London, Blakeney Area Historical Society and the Zoological Society of London.

Very special thanks to Harry, Kate, Charlotte and Hannah for encouraging me to write and to Megan McCubbin for kindly writing the foreword. I am extremely grateful to Graham and Marilyn Lubbock, Richard Porter, Ian Ward, Joe Cockram, Pete Stevens, the Trudgill family, Dan Sunderland, University College London and the National Trust for kind permission to use their photographs. Thanks also, for assistance with the editing and publishing process, to David Foster, Gerry Granshaw, Dave Wood, John Sizer, Joe Reed, Martin Perrow, Tony Martin, Isabel Sedgwick, Claire Masset, Nicola Guy, Ele Craker, Lauren Kent and my parents: Bev and TT. Lastly, thanks to the many authors and writers whose works have informed, inspired and motivated me.

Preface

Riding a Tide

WHEN YOU LIVE IN a remote former lifeboat station at the end of a 4-mile shingle spit, surrounded by sea at high tide, protecting internationally important seabird colonies, you’re often asked what it’s like. Few people have had the privilege and responsibility of living on an isolated, internationally important nature reserve, their every move judged by countless critics. This book gives me the opportunity to share my personal perspective of the joys, struggles and surprises that made life as Blakeney Point’s ranger so unique. This is the story of what life as a ranger on one of Britain’s prime nature sites is really like.

As soon as I started working on Blakeney Point, I contemplated one day writing about my experiences, from the excitement of monitoring the rapidly growing seal population to the challenges and struggles of protecting ground-nesting birds from a plethora of threats. And in spring 2020, like so many, I found myself with time to look back and reflect. For over a decade, I had been collecting information, keeping diaries of first-hand experiences and memorising stories I had been told.

Each year, hundreds of thousands of visitors come to north Norfolk to enjoy themselves and experience its inspiring landscapes and magnificent wildlife. Just the mention of Blakeney Point is enough to bring a smile to many a face. But I have had the privilege of actually living out there, in all weathers. I have gained an insight into the real Blakeney Point in her numerous guises.

I once joked that it would take a book to really explain what I have experienced and learned during my time on the Point. That became a personal challenge in 2020, and eighteen months of pleasure followed, culminating in this book.

Part 1 follows my year as a volunteer assistant warden, experiencing life on the north Norfolk coast for the first time: learning about the wildlife, tides and the complexities of managing a dynamic nature reserve. Part 2 is an account of my first breeding bird season on Blakeney Point itself. Part 3 covers my time as the Point’s full-time ranger, from dealing with a major tidal surge to solving a great seal mystery.

The title of the book refers to how the changing seasons influence weather and wildlife in a complex cycle – partly predictable, partly unpredictable. Time and tide have formed, eroded and altered the topography of Blakeney Point, creating a fascinating, ever-changing landscape that is home to a stunning array of creatures who adapt to these changes.

Since Blakeney Point became famous in the Victorian times, our relationship with it has changed. Thankfully, for the last 120 years, it has been protected. The key focus of safeguarding its vulnerable ground-nesting birds has been a constant, but the precise ways in which the Point is managed have developed, just as the whole world has changed.

In the book, I look at the changes I have both experienced and studied, sharing the love I feel for this magnificent, wild stretch of Britain’s coastline. This is my tribute to the beauty of Blakeney, to the wildlife and the people to whom it is home.

Ajay Tegala, January 2022

Introduction

Reaching a Point

MORSTON QUAY WAS CLOAKED in a thick sea mist. We crossed a wooden bridge over a tidal creek and boarded an open-topped ferry, which took us out into the disorientating greyness of Blakeney Harbour. Some time passed before a shingle finger appeared in front of us, emerging from the mist. The air was suddenly filled with the noisy cries of black-headed gulls and Sandwich terns, which were nesting behind a string fence line. On the water’s edge were dozens of common seals. It was as if we had ascended through the greyness to reach a magical wildlife island.

The boat landed and our feet crunched on shingle as we walked towards the former lifeboat house, clad in corrugated iron painted deep blue. Along the ridge, I spotted several oystercatchers. Their camouflaged eggs were protected by square stringed-off enclosures. To someone familiar with predominantly brown garden birds and inland river fowl, oystercatchers were appealing, with their distinctive pied plumage and carrot-coloured bills, which emitted a piercing call. We were intruders to their nesting grounds.

Inside the Lifeboat House, we glanced at the museum-like display about the birds and plants found in this special environment. Heading back outside, we followed a wooden boardwalk over the undulating dunes towards a bird hide. Completing a circular route, we ended back at the landing stage, where we were collected and ferried back to Morston. An hour on Blakeney Point flies by.

It was a weekday afternoon in early June, during the school half-term holiday. I was 14, and this was my first visit to this part of the Norfolk coast. Like countless others, my family was on holiday in the county and had come to see the seals. The mist made it a mysterious and eerie experience. I felt like I had entered a secret haven, a sanctuary for seals and birds. The memory would never fade.

In the early twenty-first century, the vast majority of ferry passengers come to see the seals. A smaller number are interested in the birds and a smaller number still appreciate the flora. During the late nineteenth century, neither seals nor birds were so appreciated. In fact, both were shot – with guns, rather than cameras.

Most Blakeney bird records from the Victorian era are of specimens secured by the so-called ‘gentleman gunners’. These were primarily Londoners who came to Blakeney and Cley to hunt rarities during the spring and autumn migrations. Local taxidermists were kept busy preserving and presenting the skins of birds shot by the collectors.

Horrifyingly large numbers were lost to punt guns. This impacted not only on the migrant birds on passage, but resident and breeding species too. By 1892, the oystercatcher had been completely lost as a breeding species on the Point. There was a growing need for its protection.

Although destructive, the Victorians greatly improved our knowledge and understanding of birds. Being able to examine carcasses in the hand enabled plumage and moult to be studied, which informed the identification guides we use to this day. Victorian ornithologist Henry Seebohm observed – quoting the ‘Old Bushman’– ‘What is hit is history and what is missed is mystery’.

The year 1901 was a milestone. It marked the foundation of the Blakeney and Cley Wild Bird Protection Society. A group of concerned locals came together to try to better protect the birds that came to the Point during the breeding season. Robert J. Pinchen, a butcher by trade, was appointed as the Point’s watcher at a meeting in Cley. According to Pinchen’s book, Sea Swallows, he was employed for ten weeks each nesting season on a weekly wage of 15 shillings.

Another gentleman was key to the protection of Blakeney Point. Professor Francis Wall Oliver of University College London (UCL) first visited the Point in 1904 while recuperating from pleurisy. Oliver recognised the value of the saltmarsh and dunes from a botanical point of view, with enormous research opportunities. The university purchased the now derelict Old Lifeboat House in 1910 and it became a field centre.

Oliver made regular field trips to Blakeney. He mapped the distribution of saltmarsh plants in relation to the amount of saltwater flooding they could withstand. In some ways, this work was in the vein of explorer Alexander Von Humboldt, who had done similar work across the globe a century earlier. Along with other pioneering ecologists, including Doctor Sydney Long, Professor Oliver produced numerous papers and scientific journal articles.

The unspoiled expanses of saltmarsh and largely unspoiled sand dunes might not have been protected and made accessible to the public had it not been for Oliver. Following the death of Lord Calthorpe, his north Norfolk coast estate went on the market. This included Blakeney Point. Oliver gained agreement for the Point to be used for botanical studies and to be sold as a separate lot. At his suggestion, the Point was bought by public appeal and transferred to the National Trust in August 1912. Funds had been provided by the Fishmonger’s Company and an anonymous donor: banker and entomologist, Nathaniel Charles Rothschild.

Already a bird sanctuary, Blakeney Point had now become the country’s very first coastal nature reserve. The National Trust shared UCL’s appreciation for the Point’s botany, physiography and also its ornithology. Bob Pinchen was kept on as watcher, already having eleven seasons under his belt.

The National Trust had been founded just over seventeen years previously and had managed the country’s first nature reserve, Wicken Fen, since 1899. Both Wicken and Blakeney are often referred to as the birthplace of ecology in relation to their respective habitats. Over a century on, the trust’s core responsibilities on Blakeney Point are much the same as they were when they acquired it: to protect the terns and other vulnerable ground-nesting bird species.

Four tern species breed on Blakeney Point. All four nest on the ground, laying between one and three eggs in a simple scrape in the sand and shingle. These elegant seabirds migrate to Norfolk from wintering grounds in Africa. Closely related to gulls, terns have more angular wings, forked tails and plunge-dive to catch small fish. In fact, common terns are sometimes called sea swallows because of their tails.

The Sandwich tern is the largest of Blakeney’s terns. So named because it was first described in England at Sandwich in Kent, by ornithologist John Latham in 1787. The Dutch name of grote stern is perhaps more appropriate as it translates as ‘great tern’. In 2012, this was the most numerous breeding tern on the Point, with over 3,000 pairs nesting. However, breeding was not confirmed on the Point until 1920 when the first nest was discovered.

Breeding pairs doubled in 1921, exceeded 100 in 1923 and reached around 300 pairs in 1924. Following their rapid colonisation, 1925 saw breeding numbers fall to just eight pairs. It was noted that the bulk were thought to have deserted to nearby Scolt Head Island, 12 miles west of the Point. Since that time, the north Norfolk Sandwich tern population has regularly switched between Blakeney and Scolt Head. If something made the colony feel unsettled at one site, birds would desert to the other. For a period, Blakeney was the sole breeding site and at other times it was Scolt Head. Rarely was there a year with a completely even split. Historically, there was a great rivalry between the wardens of the two sites.

Throughout the 1960s and most of the ’70s, between 1,000 and 2,000 common tern pairs nested each summer. It was in 1978 that the Sandwich tern overtook the common tern as the most numerous breeder.

The common tern has bred on the Point since before Pinchen’s time. In his first year as watcher, 140 pairs nested. Numbers increased steadily year on year, benefiting from the protection afforded. Common terns were first documented at Blakeney around 1830 but are more than likely to have been present for some time before this date. As the name suggests, the species has a far larger British breeding population than the Sandwich tern and is more widespread, nesting inland as well as on the coast.

Throughout the 1980s, between 1,000 and 3,000 Sandwich terns nested, but common terns dropped to 200–300. In the 2000s, common tern numbers dropped below 100 pairs in some years. A theory for this significant change is that the Sandwich terns had taken over as the dominant species, pushing the common terns out of the prime nesting and feeding areas and therefore making them less successful breeders.

As well as the common tern, the only other tern species known to have nested on the Point in Victorian times was the little tern, then known as the lesser tern. In 1901, there were about sixty nests. Fast forward 115 years, and breeding numbers were much the same. However, since the Second World War, over 100 nests have been recorded on a number of occasions.

In the 1970s and again in 2011, Blakeney Point supported the country’s largest and most productive little tern colony. They are, however, typically inconsistent and very sensitive, frequently suffering very low productivity. Their habit for nesting close to the high-water mark makes them vulnerable to big tides, especially when combined with strong onshore winds.

Since 1922, a small number of Arctic terns have bred at Blakeney each year. Never more than twenty-four pairs have nested in a year, this number is usually below ten and often below five. They are at the southern limit of their breeding range. Although the least common of the four species on the Point, sometimes these are the first species visitors encounter when they board the ferries in Morston Creek.

A fifth species that has previously bred is the roseate tern, Britain’s only other breeding tern. Two pairs nested between 1921 and 1930, and single pairs bred in 1939 and 1948. In 1997, a pair nested but the eggs were predated, and another unsuccessful breeding attempt was made the following year. It was only in these fourteen years that five tern species bred at Blakeney, although roseate terns are seen over the Point on passage most years. Black terns are also seen on passage most years, they bred inland in East Anglia until 1885.

Methods of protecting and counting the terns have evolved since Pinchen’s time. He would mark nests with sticks. Visitors would be allowed to walk inside the colony, looking out for the sticks to avoid trampling on eggs. Although tolerant to a certain degree, this did disturb the terns. People would picnic in the colony, causing birds to leave their nests for long periods and thus making the eggs vulnerable to chilling or overheating, depending on weather conditions, as well as giving predators the opportunity to take eggs.

After the Second World War, warden Ted Eales introduced fencing. According to his memoirs, he found some metal wire washed up on the beach. He had the idea to create a wire fence around the ternery to keep people out. This method is used to this day, albeit with road pins and baler twine instead of metal wire.

Fences and signs alone are not sufficient to protect the vulnerable terns. Especially as tides reduce the area available to fence without the risk of being washed away. A physical presence is needed to ensure nobody accidentally strays too close to the breeding colonies. This means that the job of the Point watcher-come-warden-come-ranger and their assistants involves keeping careful watch on the ternery between early April and mid-August. Stationed on the beach at low tide, they can direct seal-seeking visitors as far away from the nesting area as possible, following the water’s edge.

Watcher Bob Pinchen in the early 1920s. (National Trust)

Warden Ted Eales in the late 1940s. (John Trudgill)

This may sound simple, but often visitors accidentally stray too close to the terns. Excited by the experience of seeing seals, visitors can easily forget about the inconspicuous ground-nesting birds and some simply don’t register them at all.

The majority of visitors to the Point arrive by boat from Morston, landing for just thirty minutes to an hour. In this short time, they are not able to reach the beach – and the ternery is usually cut off by the tide, even if they do. A much smaller number of people make the 4-mile trudge westwards from Cley beach. An even smaller number wade across the harbour through thick mud and tidal creeks. Their route and timing have to be carefully chosen, with local knowledge of the dangers. Even if this specific knowledge is gained, the harbour changes from year to year, with creeks moving and sediment shifting. Tide timetables are only useful to a point, as onshore winds can cause the harbour to fill up earlier. This is nature in truly dynamic form.

Albeit far fewer in number than they once were, bait diggers come to know the many moods of the ‘fickle maiden’ that is Blakeney Point. Wind strength and direction can alter the speed at which the tide rolls in and out. When out digging for mud-dwelling worms to be used as fishing bait, up to a mile from terra firma, bait diggers must be constantly aware of their surroundings, carefully choosing the right moment to beat a hasty retreat. Time and tide wait for no one.

1

Minding the Gap

EARLY ONE JULY MORNING, Graham steered the powerboat along Morston Creek into Blakeney Harbour. Dozens of other boats were moored in the harbour; some were fishing boats, but most were pleasure craft. By far the largest was Juno, a massive sailing barge majestically dominating the harbour with its size and beauty. Barely a decade old, her design was inspired by the Thames cargo barges that were common along the east coast up until 100 years ago.

Half a decade since my first seal trip, I was now on my second trip through the harbour, during my second day as a volunteer assistant warden. Two-thirds of the way through an Environmental Conservation and Countryside Management degree, I was embarking on a placement at Blakeney National Nature Reserve to develop my skills and experience.

Cley-born Graham has lived his whole life in rhythm with the changing seasons and shifting sands, working on the reserve since the mid-1980s. He started out as a seasonal assistant warden on Blakeney Point, returning for a second season before securing a permanent role based primarily on the mainland sections of the nature reserve.

On this occasion, Graham was managing the Point for a day. He and I were holding fort while Point-based warden, Eddie, and the two seasonal assistants attended a course on dealing with confrontation.

Graham explained how all of the many mooring buoys were connected to their moorings on ropes. These ropes can get wrapped around boat propellers if they are steered too close to the buoys. That is one of the reasons why ‘all good wardens carry a knife’, something he would go on to tell me many times.

Although very much at home steering the boat, Graham was cautious. He had a respect for the environment that came from years of experience. You can’t always see what’s beneath the water at high tide, but the floor of the harbour is a network of channels and banks. Straying too far from the main channels can lead to propellers being damaged from scraping the bottom and boats can all-too-easily become, quite literally, stuck in the mud.

We followed a line of sunken willow branches, which marked the course of Pinchen’s Creek, named after the Point’s first warden. Pinchen and his family would spend the summer months based in a houseboat moored on the edge of this creek. In fact, a piece of wood from one of his old houseboats, the Britannia, remains behind the ferry landing stage, completely overlooked by the majority of visitors.

The saltmarsh beyond was a haze of purple with common sea-lavender in peak bloom, the most vivid colour in the landscape. On that Tuesday in early July, the first high tide was early in the morning and second was in the early evening, with low tide around midday. This is known to locals as a split tide: the ideal conditions for going out to the Point by boat for the day. Every other Sunday there is a split tide. Between mid-April and mid-October, during the interwar years, these were known as Point Sundays.

The ferries now rarely land for more than an hour. But, for much of the twentieth century, locals would sail out on a morning tide to spend the day on the Point. Families would relax on the foreshore and in the sand dunes or go sailing and fishing. Lugworms would be dug on the ebb tide to catch flatfish with. This, along with cockling, was a way of subsidising low weekly earnings.

At the end of the day, families would head home with their pets and primus stoves. They would usually leave their litter behind. From the age of 11, local boy Ted Eales was on the payroll as litter collector. Ted’s father, Billy, took over from Bob Pinchen as watcher in 1930.

A split tide worked perfectly for the Point’s resident wardens to have the opposite of a Point day – leaving in the morning and returning in the evening. Graham and I were taking their place for the day. The bow of the boat slowly pushed gently into the shingle of the landing ridge and Graham carefully positioned the anchor.

We trudged over the shingle as we headed towards the Lifeboat House. The same route thousands of visitors walk every summer and the one I had walked five summers before. Graham explained that we had now passed the peak of the breeding bird season, the previous three months having been the busiest time for the Point’s wardens. Most of the oystercatchers now had young, but some had experienced unsuccessful first and even second nesting attempts, so were still incubating eggs. Our task for the day was to make sure that birds with eggs could incubate them in peace and those with young could tend to them without being disturbed.

There was time for a cup of coffee first. We ascended the concrete steps to the Lifeboat House door. To our left was another set of concrete steps, which led into the visitor centre. Graham led the way into the kitchen, commenting that he couldn’t live in a place so untidy as he gestured to the array of items spread across the table. Alongside a teapot and other kitchen items lay copies of British Birds magazine, an A4 page-a-day 2009 diary and various office items. It was clear that living and working merged in this building. I felt like an intruder in the wardens’ home.

A wooden-panelled wall and sliding door separated the living quarters from the visitor centre. Pinned to it were a wide variety of invertebrate identification charts: moths, butterflies, dragonflies, bees and grasshoppers. Also pinned to the wall was a cartoon drawing of a bird blowing a trumpet, captioned ‘Trumpeter Finch’.

The kettle whistled on the gas hob and Graham asked if I wanted coffee or tea. As we sipped our hot drinks, he outlined the plan for the day. We would alternate between the beach and the Lifeboat House area, swapping over every hour. First, he would take me to the beach and set me off on ‘gap’ duty.

Walking over the boardwalk towards the beach, Graham mentioned that the recycled plastic boards had only been laid the previous autumn. He explained how the old wooden boards would get slippery when wet and rotted fairly quickly, whereas the recycled plastic – made from old milk crates – should last much longer and provided better grip. Indeed, it blended in well and didn’t look out of place. There were already lichens growing on the boards in places.

At the end of the boardwalk, we continued in a straight line towards a ridge of sand dunes called Far Point. Extending from Far Point, sits Middle Point, a block of dunes to the west. Graham pointed behind us to the end of the dunes we had just crossed on the boardwalk: there stood Near Point, where an old wooden hide was visible in the distance.

He explained how, over the years, the Sandwich terns had shifted their nesting position as the spit had grown in length, favouring the westernmost tip. Graham peppered his commentary with jokes. It was a laugh a minute, with humour injected at every opportunity. I had known him just twenty-four hours, but I already knew I enjoyed his company. He had a sense of fun, balanced by true passion for his part of the north Norfolk coast.

Low tide on the beach near the gap: all sand and sky, August 2009. (Ajay Tegala)

Through a gap in the dunes, the inky blue North Sea was visible. The gap had been worn by the footsteps of the many people taking the most direct route to the beach. A line of orange string held up by rusty metal stakes led almost to the water’s edge. A short way to the left, there was an upside-down plastic fish box positioned up in the dunes, overlooking the beach. This was to be my post for the first of many hours ‘on gap’.

Everyone who works or volunteers on the Point during the tern breeding season becomes familiar with the gap. The fish box has since been upgraded to a wooden garden chair, but the job remains the same. This is the best location to meet visitors who have walked up the Point from Cley. Whether they have followed the beach all of the way along, or cut into the dunes to the boardwalk then headed back out to the beach, this is the point where the two routes converge.

Graham explained that the tide would recede almost as far as the distant wreck marker post, which looked nearly half a mile ahead of us. He pointed out a marker buoy about the same distance to our left. This was the furthest I was to let anyone walk along the Point. I was to ask walkers to stick as close to the shoreline as possible. This way, they would be able to get a decent view of the seals without disturbing the nesting little terns on the beach. Confident that I would speak to every visitor who made it to the gap, Graham left me to keep watch.

The little tern has the highest level of legal protection of all four tern species nesting on the Point. Their rarity affords them listing under Schedule 1 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981. It is a criminal offence to disturb, intentionally or recklessly, an adult and their young on or near their nest. That year, fifty-six little tern nests had been recorded on the beach and the first chicks – half a dozen of them – had been observed only the previous day.

At low tide, seals haul out on the opposite side of Blakeney Channel to the Point, known as Stiffkey West Sands. Visitors can therefore see them from the opposite side of the water without disturbing them. That said, by far the best way to see the seals up close is on the ferry trips from Morston. The seal ferries conveniently help to protect the seals and nesting birds by providing a disturbance-free but breathtaking way for millions to appreciate the wild wonder of the Point.

As I sat waiting for the first walker of the day to appear, I took in the beauty of my surroundings. The white dots of terns and gulls flew above the deep blue of the sea. The sound of the gently lapping waves was very relaxing – although I did not feel completely relaxed because I had responsibility, a job to do. These were my first moments as a warden. As a 19-year-old student, this would shape the rest of my life, although I didn’t realise it at the time.

More than half an hour had passed before the first visitor came into view on the beach. I headed down from my vantage point, following the fence line to the shoreline. The solitary walker, in his late twenties, saw my green, branded polo shirt and began asking about the reserve and its wildlife. I was not yet knowledgeable enough to answer all of his questions, but politely communicated where he could walk to safely see seals. Having had part-time jobs centred around giving good customer service, my conversation with the walker flowed naturally and the necessary information was imparted.

Satisfied he had grasped the directions I had given, I returned to the fish box to keep watch for more people. I also followed the suggestion I had been given and tentatively kept watch on the walker, through a pair of Minox binoculars I had been provided with. He reached the buoy that marked the limit of public access and lingered there a while before eventually starting to head back along the same route he had arrived, just as I had requested. If he had continued further along the beach beyond the buoy, I would have had to jog swiftly over and ask him to return.

The reason access was limited to that particular buoy was so that visitors did not stray beyond the view of the watching warden. Merely a few hundred metres further along the beach was the very tip of the Point, where about a third of the nation’s Sandwich terns were feeding their chicks. The majority of these chicks were not yet capable of flight. In fact, that same day, the very first juvenile Sandwich tern of the season was heard calling over the Lifeboat House.

As well as the West Sands, at low tide a small number of seals would often haul out on the end of the Point. If someone was to walk too close to them, they would dart into the sea. This prevents them from resting, digesting their food and healing any wounds. Such disturbance also reduces the chances of the ferry trips seeing as many seals at the next high tide, thus spoiling the enjoyment of others as well as disturbing a protected wild mammal.

Graham arrived five minutes early. He had just been on a careful walk a short way off the boardwalk and found a partridge nest containing ten eggs. He showed me the photograph he had taken and explained this was the reason that people should not stray from paths. I left Graham at the gap and returned to the Lifeboat House to explore its lookout tower at his suggestion.

At the top of the stairs stood a simple wooden ladder screwed to the wall. As I climbed up, it creaked slightly. I pushed open the hatch and entered the lantern, where an old armchair and telescope were located, along with a few tomato plants, benefiting from the greenhouse-like conditions. This was clearly the perfect place to keep watch on the Point and the harbour. Hours could easily be lost observing the geography of the landscape.

As the harbour emptied, areas of bare mud, green saltmarsh vegetation and silvery-white shingle were becoming exposed. Saltwater rippled seaward through the main channels, with the moored boats facing the direction of the outward tide. On the exposed mudflats and marshes, small wading birds probed with their bills, searching for worms and crustaceans beneath the surface. Distant car windscreens glistened in the sun, parked on Morston Quay. The pine trees between Wells and Holkham were visible to the west and Cley coastguard shelter could be picked out to the east.

An hour later, I returned to the gap. By now, the tide had pulled out much further and a considerable expanse of sand had been exposed. Graham encouraged me to try to count the seals every hour as the tide went out. That way, I would appreciate how many more of them hauled out as the sand was exposed. Meanwhile, he headed to Pinchen’s Creek to make sure the boat was still afloat as the tide dropped. The further out from the high water mark it could be pushed, the sooner it would be afloat again on the next tide and the earlier we could use it again. Otherwise, we would have a longer wait for the water to get higher and Graham didn’t like to wait around too much, if he could help it.

During his lunch break, he had wandered carefully onto the saltmarsh and plucked a few handfuls of Salicornia, or glasswort, known more commonly as samphire and sometimes referred to as ‘poor man’s asparagus’. He told me to give it a good wash to get the mud and salt off, boil it for ten minutes and add vinegar if I fancied. Technically, it is illegal to uproot any wild plant on the reserve, but Graham explained how locals hadn’t done any harm by taking small amounts. Sustainable gathering of samphire had occurred for generations and become part of north Norfolk culture. However, high-end restaurants had now discovered it. If I spotted anyone gathering large amounts for commercial use, then I would need to take a photograph as evidence and report it.

At dead low tide, I wandered down to Pinchen’s Creek. It was now almost completely empty, its steep sides clearly visible. There were a few marks in the mud where boat propellers had evidently scraped the bottom. I was fascinated by how different the harbour looked at low tide and also the number of birds that were feeding on the saltmarsh now that it had been uncovered, like a curtain lifting.

The main sand dunes are a vastly different place to the marsh. Cushions of grey green cladonia lichen crunch underfoot, dried by the sun. The antler-like branches of the lichen earn it the nickname reindeer moss. When it rains, the lichens rehydrate, softening and changing colour to a deeper green. The shingly lows of the dunes are dominated by tiny tussocks of coarse grey hair-grass, a nationally rare plant of which Britain has more than 25 per cent of the world’s population.

I’m not sure what Graham’s first impressions of me were. Probably a quiet, slightly shy 19-year-old, clearly with limited experience of boats or coastal environments. But perhaps someone keen to listen and learn, willing to get stuck in and develop as many skills as possible; someone eager to soak up the wisdom of those who had grown up surrounded by coastal wildlife. I know he appreciated having an extra person on the ground; an extra pair of eyes and hands to help keep a lookout and protect the reserve he cared so much for; an extra voice to speak to visitors … and a fresh set of ears to listen to his jokes and ‘true stories’!

2

The Freshes

IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, a four-storey tower windmill was built north of Blakeney Church, at Friary Farm. The 32ft-high flint tower overlooks Blakeney’s freshwater grazing marshes, an area of reclaimed saltmarsh that was enclosed by a sea wall around 1650.

Corn was ground in the windmill throughout the nineteenth century, but in January 1912, the Blakeney miller was declared bankrupt, and it came into the ownership of Lord Calthorpe, who also owned Blakeney Point. When he died, there were plans to convert the windmill into a residential house. However, it has laid derelict for over a century. It was left to the National Trust in 1983, who maintain the building in the hope that it may be possible to restore it one day.

During the 1990s, the Blakeney National Nature Reserve office and workshop was moved from Morston to Friary Farm. After half a decade of planning, a single-storey flint building was built adjoining the flint wall that surrounds the old windmill. It imitated a previous building, shown in old photographs, of which only the original base remained. The reserve now had volunteer accommodation on the mainland.

The first residential volunteer to stay there, Reuben, went on to become an RSPB – Royal Society for the Protection of Birds – reserve manager at Leighton Moss in Lancashire. He kept in touch with Graham and his wife, Marilyn, who started working for the trust around the same time. Marilyn had taken up a six-month post doing administration at the Blakeney reserve office in 1998 and ended up working there for more than two decades.

I arrived at Friary Farm on a sunny Sunday afternoon, winding my way around the luxury static caravans to the Blakeney reserve office adjacent to the caravan park. Seasonal warden Chris met me and gave me a key for the volunteer accommodation beside the windmill. He directed me to the room beside the kitchen, stating that the other bedroom was for the lads on the Point to use on their days off.

That evening, seasonal Point warden Richard had a night off. Richard had spent the previous summer as a seasonal warden on the Farne Islands in Northumberland, also managed by the National Trust. He spent most of his days off birdwatching on the Point, in search of rare migrants. But now that the spring migration was truly over, he was using his weekly days off as a chance to explore the Norfolk coast.

We walked the short distance to Friary Hills. These had been formed by glacial deposits at the end of the last ice age. There was a time when the sea reached right up to the base of them, where wharves were created for boat building and repairs. Standing on top of a bench to see over the mass of gorse, we looked out over the Blakeney Freshes. Richard casually commented how it wasn’t a bad back garden. This was to be my back garden for the next year.

Before me lay a patchwork of lush, green fields, silvery water and swishing reeds dotted with bushes. The Great Barnett, formerly a tidal creek, carries water from the River Glaven through the middle of Blakeney Freshes and out into the harbour through a culvert. The water levels are carefully managed throughout the year to create optimum conditions for breeding waders and overwintering wildfowl.

Over the course of my year volunteering on the reserve, I went on many walks along the coastal path around Blakeney Freshes. From the hills, one morning, I was treated to my first view of an otter. It bounded across an open field before disappearing into the reeds.

On a cold evening in February, after hours of searching, I finally caught my first view of a special bird I had longed to see for years – the bittern. A magic, milestone moment.

As a child, I had enjoyed identifying birds on the River Welland and at the Peakirk Waterfowl Gardens. Grey Herons were my favourite – seeming so big to a small child. I flicked through my parents’ Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Ireland and saw the other birds in the heron family: purple heron, spoonbill and bittern. I made it my mission to one day see them all in the wild.

The spoonbill was relatively easy to see during my first week in north Norfolk. I went to Cley Marshes, lifted up the hide flap and there was one on a scrape. Bingo! Although it did tease me by initially keeping its bill tucked away as it rested.

On the edge of Blakeney Freshes is a small wildfowl collection: a selection of exotic ducks with clipped wings owned by the Blakeney Wildfowling Association. It reminded me of Peakirk. Richard hated it, saying that people come to Blakeney and the first birds they see are non-native species in captivity. Conversely, the Point’s other seasonal warden, Paul, pointed out that a lifelong appreciation and interest in birds can begin with the opportunity to easily access and observe them up close. It quickly became clear to me that, within the small and close-knit Blakeney team, there was a range of different opinions of what conservation meant. I could usually see both sides.

Over the course of my first few weeks at Blakeney, I spent much time on the Freshes with Chris and Graham, learning my way around – which ditches had crossings, which didn’t, where we could and couldn’t drive the various estate vehicles, which fields the trust owned and who the various other local landowners were.

One of the owners had built a private boardwalk into the reeds where the ‘ping’ of calling bearded tits (or ‘bearded reedlings’, as Chris called them) could be heard. These small, moustached birds are more often heard than seen, staying out of sight on windy days, tucked away in the safety of the reedbed – and most days seem to be windy on the Norfolk coast.

Chris taught me that birdwatching – in particular, his monitoring of breeding birds – is about patience and being able to relax into it. Much better to wait patiently in the same spot than to keep frantically dotting around and missing, or even disturbing, what you are trying to observe.

Three years previously, the north-east corner of Blakeney Freshes had become separated by a wide man-made channel. Shingle from Blakeney Point getting pushed into the River Glaven, where it enters Blakeney Harbour, was increasing flood pressure further upstream. Cutting a wide new channel a few hundred metres south enabled more water to be washed out to sea more quickly, solving this problem.

The result was a sort of no-man’s-land between the Point and Freshes: Chapel Island. So named due the flint foundations of a medieval building on the slightly raised ground of Blakeney Eye, Faden’s 1797 map of Norfolk marks the building as ‘chapel ruins’. A map from 1586 shows a man with dog and rabbits, suggesting it may have been a warren lodge. The discovery of a coin, found during excavations ahead of the river realignment, suggests that it may have been a toll building where ships were charged and possibly also blessed before heading out to sea. Indeed, Cley had one of the country’s busiest ports between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries.

An unforgettable moment occurred during my first few days on the Freshes. I walked along the edge of the Great Barnett, through the rough grass. Suddenly, a large bird emerged from behind a tussock, just a few metres ahead of me. Seemingly as shocked as I was, it took to the air clumsily, half-flying towards the reedbed. I knew instinctively that this was one of the juvenile marsh harriers that had hatched nearby, now developed enough to fly but still mastering the art. Practically making eye contact with such a rare bird was awesome, but the encounter also gave me a greater appreciation for how vulnerable young birds are, even large raptors.

Managing natures reserves is a fine art of balancing access and conservation. Giving everyone access to nature is so important. Sir David Attenborough famously stated, ‘No one will protect what they don’t care about, and no one will care about what they have never experienced.’

Throughout my time at Blakeney, I encountered the many ways people can experience wildlife: from the stunning seal trips to the miles of footpaths offering wild views. Like my colleagues, I shared my enthusiasm and growing understanding of the reserve with visitors, encouraging them to support our conservation work. But the marsh harrier experience highlighted the importance of ensuring certain areas are free from human access for the benefit of wildlife. Some creatures really do need space away from people.

Except for the old cart track, which intersects the eastern side of the Freshes, there is no public access onto them. The coastal path, running along the top of the sea wall, gives walkers pleasant views from a safe distance. Wildlife can behave naturally, providing dogs are kept under close control, as dogs are seen by birds as predators.

They are also seen as predators by cattle. In contrast to the relative wilderness of Blakeney Point, the Freshes are very much a managed habitat. As well as controlling the water levels and creating ponds for wildfowl and waders, the grass height is managed for their benefit. This involves cattle grazing between May and October using local tenants.

On my early orientation walks around the Freshes, I was taught how to behave around the cattle. Always closing gates and ensuring they are securely shackled was obvious, as was identifying the bull in the herd. It was also very important not to get between calves and their mothers.

The farmers were responsible for daily welfare checks and any supplementary feeding, which was more for the benefit of being able to handle them than for their diet as there was ample vegetation for them to eat. Whenever we brought the HiLux or Land Rover Defender onto the fields, the cattle would associate it with being fed, so passing through gates needed to be swift and smooth to avoid being followed too closely.

The ditch between field numbers 6 and 7 was shallow in summertime and frequently crossed by the herd. On one occasion, a calf making the crossing had strayed into a deeper section of the ditch and become stuck. Chris and I found it. By this time, the rest of the herd had moved on, leaving it alone, tired and weak from struggling. The owner was called immediately and was nearby, so he was able to come and save its life. Such is the diversity and unpredictability of a warden’s job, often being first on the scene of unexpected incidents. Fortunately, this one had a happy ending. To prevent any further danger to the cattle, we placed several large flints along the crossing point to reduce the depth of the water.

Where grazing cattle are involved, ragwort control is necessary to prevent them ingesting it. This is most prescient when grass is being harvested for hay, as dried ragwort is more likely to be eaten than fresh plants growing in fields, which most livestock tend to instinctively avoid. Although ragwort is an important nectar and food source for many insects, uprooting this toxic plant is a job almost every conservation volunteer will experience. I was already acquainted with it from previous work experience at Deeping Lakes with the Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust.