Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

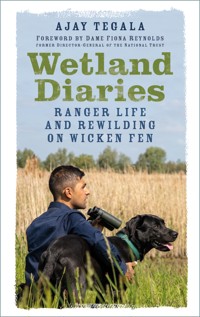

'Ajay's passion for conservation and his encyclopaedic knowledge of Wicken Fen ooze out of every single page' - Iolo Williams Tucked away in the flat lands of rural East Anglia lies Wicken Fen, so loved for its big skies and tiny creatures, boasting over 9,000 recorded species. For 125 years, this wildlife sanctuary has been cared for by the National Trust. A dedicated team look after this precious wetland of international importance, working with herds of free-roaming horses and cattle and weathering the elements to cope creatively with the dramas of a life outdoors at the cutting edge of conservation. Wetland Diaries is a seasonal account of ranger life on Wicken Fen, saving a once widespread landscape and revealing the spectrum of emotions experienced in the process. Ajay shares the spirit and atmosphere of the Fens, offering an insight into the privileges and pressures of managing semi-wild animals in one of the country's first wetland restoration projects, creating precious breathing space for nature and people alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 374

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover photograph © Mike Selby

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Ajay Tegala, 2024

The right of Ajay Tegala to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 349 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Dedicated to

All of my family,

Carol Laidlaw and the

Wicken Fen staff and volunteers

I have worked with over the years.

And young naturalists everywhere.

Charles Lucas (1853–1938)

Eric Ennion (1900–1981)

Alan Bloom MBE (1906–2005)

Ralph Sargeant (1942–2016)

Short-eared owl. (Joss Goodchild)

Map of the Fens. (Ajay Tegala)

Contents

Praise for Wetland Diaries

About the Author

Foreword by Dame Fiona Reynolds

Acknowledegments

Introduction: As Far As the Eye Can See

Brief geography and history of the Fens – Peat – Growing up in the Fens – Ranger life on Wicken Fen

1. The Mists of Time: My Long Road to Wicken

A foggy fenland walk – A mysterious fen-edge ride – Fen folk – A humid evening on Harrison’s Farm – Drainage of the Fens – History of Wicken Fen – ‘Cock-Up’ Bridge – My family moves to East Anglia

2. Finding the Fen

First walk around Sedge Fen – Management of Wicken Fen – Introducing Carol – How to become a warden/ranger – Scrub clearance

3. A Week at Wicken

Teenage work experience – Sedge harvest – Flora and fauna of the fen – Beginning a career in conservation – Studying and volunteering

4. Rewilding

Extinction of the swallowtail – The Wicken Fen Vision – Defining the term ‘rewilding’ – Returning farmland to fenland – Grassland and wetland birds – Death and rebirth of Burwell Fen – Arrival of the Koniks – First foal on the fen – Arrival of the Highland cattle – Other British rewilding projects

5. Carol, the Cattle, the Koniks and Me

First day as a fen ranger – New Forest Eye – Cattle handling – Meeting the herds – Ear-tagging calves – Livestock management – Horse behaviour – Our relationship with the horse – Euthanasia – Naming – Dung sampling – Ada gets stuck – Mare crosses river– Gale gets out – Vasectomies

6. Nature Takes Over

Pandemic – A glimpse of the past – ‘Lockdown’ life – Corncrake surprise – A difficult birth – Reopening – Bareback riders – An evening dip – Selling horses – Cutbacks – Making hay – Christmas Eve – Selling cattle – Springwatch – Oakley – Water vole at Judy’s Hole – Invasive non-natives

7. Wetland Management

Water abstraction – Bumpy old droves – An ancient river – Guinea Hall Fen – The Fen Harvester – Reedbed management – Wartime reclamation – Return of the crane – Sustainable conservation of wildlife

8. Winter Days

Hen harriers – Resting Sedge Fen – A vet visit – A fence fails – Winter wonderland – Seeking the bittern – Life and times of Tim

9. Signs of Spring

World Wetlands Day – Larks ascending – Preparing for spring – An awesome owl encounter – Rambling – Out in the tractor – Snowballs – A stork drops in – Handling horses – Spring flowers and migrant birds

10. Blue Skies, Birdsong, Blooms and Booms

Booming bitterns – First foal of spring – Wild Isles – Calf banding – Toby and other friendly bulls – Brimstones and blossom – Easter egg hunt – 120th birthday – A shock in the car park – Dawn chorus – Bittern watch – A lone nightingale

11. Green to Gold

Dragonflies – Orchids – Cuckoo – Breeding bittern behaviour – Pout Hall Corner – Bats in the cafe – Summertime – Nocturnal insects – The fen nettle – A missing bull – Cranes fail again – The ‘ugly cygnet’ – The joys of raking – The wheatear heralds autumn

12. Weird Wicken

Ghost walk – The missing policeman – The lantern men of Wicken Fen – Fen blows – Storm Eunice – The drought of 2022 – Ralph – A cocky bird – A bogie bird – Swallows and a super blue moon

13. Ever Onward

‘If Wicken Fen was a person ...’ – Reserve reflections – Safeguarding soil – Herd welfare – The complexities of rewilding – Access and conservation – Diversity in the countryside – Hopes and dreams – Happy here

Bibliography

Appendices

Appendix 1: Species Recorded on Wicken Fen

Appendix 2: Notable Koniks Mentioned in the Text

Appendix 3: Notable Cattle Mentioned in the Text

Appendix 4: List of Ajay Tegala’s Media Appearances

Praise for Wetland Diaries

‘Ajay’s passion for conservation oozes out of every single page.’

– Iolo Williams, wildlife TV presenter.

‘A wonderful celebration of fenland history and wildlife by an inspiring ranger working at the forefront of wetland conservation.’

– Nick Davies, field naturalist and zoologist.

‘Ajay’s vivid words and illustrations capture life as a ranger in one of Europe’s most important nature reserves. Wetland Diaries has the pace and energy of a thriller, as it reveals the evolving relationships of wetland plants, birds and grazing animals in an age of potentially disastrous climate change.’

– Francis Pryor, archaeologist, author and TV presenter.

‘Aloe vera for the soul. I fell willingly headfirst into this glorious volume about the beauties of nature, written with all the respect and sensitivity one expects from Ajay.’

– Milly Johnson, bestselling romantic fiction author.

‘Ajay’s deep connection to Wicken Fen and its wildlife shines through in this gentle deep-dive into the soggy, boggy, reed-rustling world of the Fens. Wetland Diaries offers a unique and highly knowledgeable insight into a life dedicated to protecting nature.’

– Leif Bersweden, botanist and author of Where the Wild Flowers Grow.

‘A wonderfully evocative account of life as a ranger on one of Britain’s oldest and best-loved nature reserves, packed with delightful stories of the people and wildlife, and written by one of our brightest young naturalists.’

– Stephen Moss, naturalist, author and TV producer.

‘Ajay’s evocative, measured tone holds you as he guides you through tasks both great and small. You are by his side as he cares for livestock, jumps for joy at rare birds, grubs out scrub or says goodbye to old friends as a vet sees them through their final hours.

This is a truly lovely read, non-sensational and deeply loving; it comes from a heart that is utterly in tune with the wildlife of the fen and what it takes to protect it. A book to hold close, a soft down-duvet of a book that will stay by you whenever you need a nature-loving friend.’

– Mary Colwell, environmentalist, author and campaigner.

‘A wonderfully deep dive into a fascinating and important part of the country. The book is full of practical insights and a pleasure to read.’

– Tristan Gooley, award-winning author and natural navigation expert.

‘Ajay’s intimate knowledge and experience of the place makes this a ‘must have’ book on this outstanding wetland. From the original 2-acre purchase, Wicken grew to retain existing habitat and, more recently, the previously drained fen used as farmland has been reclaimed for rewilding. Ajay reveals that management by grazing of semi-wild horses and cattle is moving wetland restoration forward dramatically.’

– Roger Tabor, biologist, naturalist, author and broadcaster.

‘In a dizzying, disquieting world, Ajay has the rare gift of remaining quietly steadfast and true to his mission and passion. A wonderful book, and the next best thing to being there oneself.’

– Gillian Burke, wildlife TV presenter.

About the Author

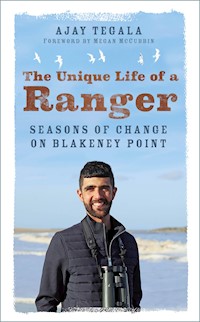

AS A WILDLIFE PRESENTER, Ajay Tegala loves sharing his passion for the natural world. His BBC television credits include Springwatch, Winterwatch, Wild Isles, Inside the Bat Cave, Coast, Countryfile, Celebrity Eggheads, Curious Creatures and Teeny Tiny Creatures. Ajay’s notable radio appearances include BBC Four’s Living World and Ramblings.

As a countryside ranger, he is grounded in the world of nature conservation. A week’s work experience with the National Trust on Wicken Fen inspired a 15-year-old Ajay to become a ranger.

Ajay grew up in the South Lincolnshire Fens. He completed a degree in Environmental Conservation and Countryside Management at Nottingham Trent University. After graduating, he became Blakeney Point ranger for the National Trust on the Norfolk coast. His first book, The Unique Life of a Ranger, shares his coastal experiences.

In 2018, Ajay moved back to the Fens, returning to where he began his conservation journey. As part of the Wicken Fen ranger team, he protects important habitats and species, watches over herds of semi-wild grazing herbivores and inspires visitors.

Other projects include his imaginative theatre shows A Year of Birdsong and Bird Songs and Witching the Wild Year, multiple appearances on the award-winning Get Birding podcast and writing for BBC Countryfile and Wildlife magazines. You can follow @AjayTegala on social media.

www.ajaytegala.co.uk

Foreword

BY DAME FIONA REYNOLDS

WICKEN FEN MUST BE one of the most written about and researched nature reserves in the country. From the Victorian Cambridge University academics to use it as a study base, through Nick Davies’ wonderful cuckoo research alongside many others, the Fen has revealed its secrets many times and in many ways.

But never like this. Ajay Tegala’s frank, on-the-ground, sometimes wide-eyed and always passionate revelations bring something new, and invaluable, to the debate about how to restore Wicken Fen’s decimated wildlife, and how to fulfil the National Trust’s commitment to this, its first ever nature reserve.

Acquired in 1899, at the very beginning of the Trust’s life, it’s only in the last twenty years or so that the Trust has been proactive in seeking positive nature recovery as opposed to hanging on grimly to the remnants of a richer (wildlife) past.

So, the story Ajay tells, of the Trust getting to grips with management regimes that will deliver nature recovery, is a new one. And he tells it well, generous in his admiration for his ranger and other colleagues, and excited by the results as they explore new ideas and bring in a key ingredient – grazing animals.

It’s not glamorous being a ranger, and Ajay’s descriptions of what’s involved are moving, sometimes funny, and often down to earth (who knew, for example, how to castrate a calf, or that poo monitoring was an important part of a ranger’s role?). But above all, it’s a totally authentic account of how someone who longed to be a ranger has become one, and a brilliant one at that.

Ajay reminds us eloquently of the crucial importance of nature recovery and of how the lessons learned at Wicken will help nature in wetlands everywhere. But Ajay’s own story, as one of a handful of ethnically diverse rangers in the Trust, is just as fascinating. As we follow his journey, accompanied by his loyal Labrador Oakley, we just want to hear more.

Dame Fiona Reynolds,Director-General, National Trust (2001–12)

Acknowledgements

FOR THEIR SUPPORT AND company on Wicken Fen over the years, in alphabetical order: Nick Acklam, Lois Baker, Ann Beeby, the late Tim Bennett, Kayley Bentley, Steve Boreham, John Bragg, Judy Brown, Josh and Julia Burling, Mel and Maggie Carvalho, Rose Chalker, Andrew Chamberlain, Peter Charrot, Howard Cooper, Jason Cooper, Hugh Corr and Carole Hornett, Dan and Steve Courten, Paula Curtis, Lizzie Dale, Alan Darby, Nick Davies, Matt Deacon, Maddie Downes, Colin Dunling, Anita Escott, Jemma Finch, Sally Fisher, Tim Fisher, Amanda and Paul Forecast, David Fotherby, Laurie Friday, Joss and Martin Goodchild, Peter Green, Kerry Griggs, Julia Hammond, Alexa Hardy, Beck Hawketts, the late Michael Holdsworth, Joe Holt, Keith Honnor, Leanna Howlett, Matthew Hudson, Francine Hughes, John and Gemma Hughes, Jenny Hupe, Kevin James, Lesley Jenkins, Alan Kell, Phil Kelly, Jonathan Kirkpatrick, Julie Kowalczyk, Carol Laidlaw and Gez Smallwood, Neil Larner, Martin Lester, the late John Loveluck, Alex Margiotta, Tony Martin, Harry Mitchell, Anita Molloy, Richard Nicoll, David Nye, Emma Ormond-Bones, John Pace, Martin Parsons, Josh Pearce, Mark Peck, Wayne Plumridge, Katie Reader, Sally Redman-Davies, Trina Roberts, the late Alan Rodger, Mike Rogers, Chloe Rothwell-Green, the late Ralph Sargeant, Derah Saward Arav, Isabel Sedgwick, James and Mike Selby, Ellis Selway, Norman Sills and Linda Gascoigne, Sarah Smith, Chris Soans, Karen Staines, Dave Stanforth, Pete Stevens and Bruna Remesso, Jackie Stone, Fiona Symonds, Rachel Tarkenter, Chris Thorne, Christine Tonkins, Luke Underwood, Toby Walker, Stephen and Ulrike Walton, Stuart Warrington, Jack Watson, Chris White, Tony Winchester, Andy Wood, Louise Young, Julie Zac, Christoph Zockler and many other volunteers, colleagues and conservationists who I have had the pleasure of working with and learning from.

Huge thanks, of course, to my family for their support and encouragement, too.

Special thanks to the National Trust – who have cared for Wicken Fen since 1899 and employed me in various roles since 2010 – for their enthusiasm towards this book. Thanks also to Jill Peak, Mike Petty, Cambridge Central Library, the University of Cambridge, Anglia Ruskin University, Burwell Museum of Fen-Edge Village Life, Vet 3 Equine Care, Isle Veterinary Group, Liz Bicknell and Bob Walthew.

I am especially grateful to Dame Fiona Reynolds for kindly writing the foreword and supporting the Wicken Fen Vision project during her time as Director-General for the National Trust. A massive thank you to my colleague Carol Laidlaw for her inspiration, encouragement, suggestions and for generously sharing her wealth of knowledge on Wicken, Koniks and Highland cattle.

Thanks also to Carol for kind permission to use her photographs, alongside those of Mike Selby (including the front-cover image), Richard Nicoll (www.richardnicollphotography.co.uk), Simon Stirrup, Kenny Brooks, Kate Amann, National Trust Images, the Cambridgeshire Collection and everyone else whose photographs appear in the book. Very special thanks to local artists Joss Goodchild and Di Cope, and wildlife artist James McCallum (www.jamesmccallum.co.uk), for kind permission to feature their beautiful artwork, and to Victoria Ennion for the privilege of featuring historical paintings by her grandfather.

For assistance with the editing and publishing process, I am grateful to David Foster and Gerry Granshaw at DFM, Claire Masset and Jeannette Heard at National Trust head office, Jemma Finch at National Trust regional office, Wicken Fen’s General Manager Emma Ormond-Bones, Stuart Warrington for kindly sharing his historical Wicken wildlife knowledge and collating the total species count (see Appendix 1), Carol Laidlaw for her diligent proofreading, John Hughes and Isabel Sedgwick for sharing their memories and wealth of Fen knowledge and to Nicola Guy, Elizabeth Shaw, Lauren Kent and all of The History Press team for their support and enthusiasm.

Lastly, sincere thanks to the following positive people along the way: Harry and the hound, Mum and Dad (Bev and TT), Grandma Reen and my late Grandad, Zinzi and Stephen, Ronan and Sarah, all my other Haywood and Tegala family, Di, Hannah, the Mitchells, Zoë and Dylan, the Deeping Lakes gang (Dave, Norah and Brian in particular), my A-Level geography teacher Heather Blades, my lecturers at Nottingham Trent University (including Julia Davies and Louise Gentle), the Norfolk coast crew, Nikki, the Abbey Girls (Gemma, Anwen and Emily) and Quizzy Rascals.

Introduction: As Far As the Eye Can See

• Brief geography and history of the Fens • Peat • Growing up in the Fens • Ranger life on Wicken Fen •

WHEN I LOOK AT a map of England and Wales, I see the face of Old Father Time in profile. Pembrokeshire is his pointy nose, the Bristol Channel forms his open mouth and the West Country is his elongated, bearded chin. On the other side, north-east of London, the ear-shaped bulge of East Anglia protrudes from beneath England’s biggest bay, the Wash. Spreading inland from this estuary – into the counties of Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire and western parts of Norfolk and Suffolk – are 2,500 square miles of low-lying former marshland. The Fens.*

Location of the Fens. (Ajay Tegala)

Southern Britain: the smiling face of Old Father Time. (Ajay Tegala)

In ancient times, these flat lands were forested with alder, birch, oak, pine and yew. Known as bog oaks, some of the trees fell into the damp, peaty soil, lying preserved for around 5,000 years. Peat is formed when waterlogged soil conditions prevent dead vegetation from decaying completely. Once drained, this black soil is ideal for agriculture. With such a high water content, peaty soil shrinks considerably when it is dried out. Since the seventeenth century, more than 99 per cent of the Fens have been drained. It is only in the twenty-first century that the environmental importance of peat has been appreciated. Although peatlands cover only around 3 per cent of the world’s land surface, they store up to a third of the planet’s soil carbon, twice as much as Earth’s forests.*

For the first eighteen years of my life, home was Market Deeping in the South Lincolnshire Fens, described by Francis Pryor as a ‘charming town, just sufficiently distant from Peterborough to retain its local character’. The name Deeping means ‘deep place’ in Anglo-Saxon language. As a youngster, I was captivated by wildfowl on the River Welland (an ancient tributary of the Rhine) and occasional sightings of lapwing flocks on farmland. Beyond the edge of town, the flat land seemed to stretch as far as the eye can see. All 47 square miles of Deeping Fen have been drained. It had once been a haven for the now rare wetland birds I lovingly looked at in my parents’ copy of the Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Ireland, dreaming of one day beholding a bittern. At primary school we learned about how wild the Fens once were and how threatened nature had become. Annual slideshows by local bird photographer Nick Williams were a highlight of my school year.

From the age of 30, I have lived and worked in the fenland within Cambridgeshire’s north-eastern quarter. Ranger life on the National Trust’s Wicken Fen National Nature Reserve involves protecting a precious remnant of largely undrained and uncultivated fen** and creating more wetland habitat to benefit the birds I have loved all my life. The protection of peat has risen in importance just as the practice of conservation grazing with large herbivores has grown in popularity. At the very beginning of the twenty-first century, herds of free-roaming horses and cattle were introduced to Wicken Fen in order to manage the habitat in a semi-wild manner. Managing both the sacred fragment of virgin fen and this adjoining landscape restoration project brings with it joy and challenge in equal measure.

I have been fascinated by animals and inspired by colleagues. I have seen all weathers, from drought to flood, snow to strong winds. I have watched misty sunrises and fiery sunsets. I have listened to beautiful dawn choruses and been bitten by mosquitoes at dusk. There are flashes of bleakness, moments of sheer solitude and delightful delves into a lost landscape. Maybe flat, never boring.

These are my tales from the flat lands, a wild life on Wicken Fen – including Burwell Fen – with glimpses of times past and Fenland folklore. Join me, my faithful Labrador, the charismatic livestock and a dedicated team of staff and volunteers who protect this very special, often overlooked piece of rural Britain for future generations.

Ajay Tegala, CambridgeshireJanuary 2024

Map of Wicken Fen and Burwell Fen with selected place names. (Ajay Tegala)

1. Norman’s Mill

2. Visitor Centre

3. Old Tower Hide

4. Norman’s Bridge

5. ‘Cock-Up’ Bridge

6. Pout Hall Corner

A colour version of this map appears at the end of the central plates section.

_________________

* A fen is defined as a low area of marshy or frequently flooded land. Fens are fed by alkaline groundwater, whereas bogs are rainwater-fed and acidic.

* Source: Global Peatlands Initiative (2022).

** Wicken is one of just four remaining fens in East Anglia, all in Cambridgeshire. The other three are Chippenham Fen, Holme Fen and Woodwalton Fen.

1

The Mists of Time: My Long Road to Wicken

• A foggy fenland walk • A mysterious fen-edge ride • Fen folk • A humid evening on Harrison’s Farm • Drainage of the Fens • History of Wicken Fen • ‘Cock-Up’ Bridge • My family moves to East Anglia •

Ouse Valley: Monday, 14 November 2022 (Part One)

Oakley bounds along the farm track a few yards ahead of me. He heads straight to the apple trees, seeking fallen fruit. Next, he forages along the woodland edge for a good stick. We have both come to know this place well over the last few years. I watch the wildlife while he sniffs the scents.

Autumn is a favourite season in the Fens. This one has been particularly mild. Dusk is twenty minutes away, but the temperature is 12°C. I unzip my jacket, feeling warmer than I have all day, sat at my desk, barely moving anything but my fingertips, occasionally lifting an arm to take a sip of tea. Now, blood is circulating as fresh air fills my lungs.

The fog has not lifted all day. Beads of water cling to every blade of grass, transferring to my wellies as I walk briskly behind Oakley. His black, furry legs are wet and shiny from trotting through the taller grass beside the ditch. It doesn’t take him very long to find himself a stick. Looking longingly up at me, I know what he wants me to do. I pick up the brittle branch and throw it along the track ahead. He races after it, overshoots, skids and backtracks to pick up what is now two smaller sticks. I choose the slightly longer of the two and launch it a little further this time. Oakley still overshoots in his enthusiasm, racing off before the stick has even become airborne.

My hands are wet from picking up the dog-stick. And so is my right foot, thanks to a recent split in my boot. Little over a minute later, my left foot also feels soggy. Why does every pair of wellies I own seem to split so quickly? Oakley’s stick is falling apart too, now barely 3in long. But he is still more than happy to play fetch with it.

My attention diverts from Labrador to wildfowl as four grey birds fly overhead. They are in fact white. I heard their honking calls before I saw them, whooper swans (pronounced ‘hooper’). A family group fly in front of us, two adults with two young hatched in Iceland six months ago. The swan calls are both softened and magnified by the damp air. There is hardly a breath of wind. Such silent stillness is rare in the exposed fenland of East Anglia. I treasure days like this. With visibility reduced, your eyes focus on what is near while your ears can tune in to what is further away. I am literally a mile from the nearest person, a farm worker sat inside a tractor, its lights only just visible in the distance. A freight train speeds across the railway bridge, crossing the Ouse Washes towards Ely Cathedral.

The sound of the train fades. My ears tune in to greylag geese on the other side of the riverbank. Their cackles linger in the air, like the water droplets sitting on my waterproof jacket. Not rain, but fog. Even the moisture soaking my socks feels like a friendly extra layer of warmth. I am genuinely happy. And relaxed. At last. No longer thinking about my to-do list, but free in the Fens. Wet feet seem to bind me to my surroundings, the landscape and its history, too.

Before this corner of north-east Cambridgeshire was drained, wet feet would have been a familiar part of life for the Fen folk. Or cleverly avoided by wearing stilts. There are tales of formidable Fen Tigers fighting against drainage and people putting grass in their boots to keep feet cool in summer, especially 12 miles south-east in the Fen-edge villages of Burwell and Wicken. I think about the lives of these stoic Fen people of old and remember how I came to learn about them 20 years ago.

Judy’s Hole: Saturday, 27 April 2002

I hurtle down Toyse Lane on an old blue bicycle, air rushing past as I race along. Barely needing to pedal, I veer right, onto North Street. The ground levels out as the Newmarket chalk hills sink beneath peat and clay. This is the Fen-edge and once upon a prehistoric time would have been the coast. History and geography merge in my 12¾-year-old mind, pondering which way to steer the handlebars. I am free to navigate a village I have visited regularly throughout my childhood, now exploring it solo for the first time.

Do I turn left along towards Factory Road and the river? Or do I continue north? I feel drawn towards the river. But an early memory becomes clear in my mind. The only time I have been this way before was on a family walk one sunny day when I was small. On that riverside ramble, I had developed an intense headache, prompting an abrupt return to Fenview 11, where I lay on the sofa in pain. This memory influences my decision. Today, I will follow North Street, staying in the safety of the village. However, the road soon leads beyond Burwell. Venturing onward, I see a finger-post marking a public footpath to the left.

On this mild and pleasant spring afternoon, the verges are verdant with cow parsley on the cusp of bursting into flower. I follow the track along the edge of a thicket, about an acre in size. Although the ash trees are not yet fully in leaf, their density is enough to reduce the sunlight. Ahead, the trees thin. A battered old caravan stands half in a hedge, it must be some years since its wheels touched the road. Beyond, a narrow footbridge, with yellow handrails, crosses the river to a bungalow. In my childish mind, I decide this is a witch’s house, acknowledging the air of spookiness this remote place evokes.

Enamel flour tin, Judy’s Hole, 27 April 2002. (Ajay Tegala)

At the same time, there is a feeling of calmness. It is peaceful and pretty. Intrigue takes over as I spy a trail leading into the trees. The ground drops 2ft, carpeted in a mat of clinging ivy. On the edge, a thin elder trunk has been sawn off at waist height. Hanging on it, there is a 1930s enamel flour tin with a stick poking out. Creating a story in my mind, I decide this must be a witches’ brew, concocted by the owner of the waterside dwelling. But it merely contains a handful of soil and some dry grass.

I cycle back to Fenview 11 to fetch my sister so I can show her the intriguing, secluded spot I have discovered. Next morning, I feel compelled to visit again, this time with my brother. Neither of my siblings quite share my intense fascination with the place.

The last time I felt such a combination of intense curiosity and subtle unease was at Eden Camp Second World War Museum in North Yorkshire, on a school residential two years before. There, one of the immersive displays recreated the terror of a night-time air raid. Around the corner, a female mannequin, in a green boiler suit, was serving soup. I found her vacant expression as haunting as the Blitz scene. Behind this frightening figure was a 1930s enamel flour tin, identical to the one in the thicket.

Every time we visited my grandparents in Burwell, I would feel lured to the waterside, always checking to see whether the flour tin was still there. It always was. Eventually, the elder trunk was removed, the tin left lying on the ground, becoming increasingly worn and weathered.

A decade passes. I return to the area and wonder whether the old tin could possibly still be there. Heading to the spot to scan the ivy-clad ground, a flash of white catches my eye. There it is. Bent out of shape with one of its handles missing. I feel a rush of nostalgia and a sudden, uncontrollable urge to rescue it, take it home with me. I pick the tin up and carry it to my car, certain that nobody else could possibly have more of a connection to it than I do.

From my first visit, I knew there was something special about this place. It was wild, wonderful and witchy. So intriguing, idyllic and intoxicating. I felt a sense of solace, sanctuary and escapism. There had to be something more to it. And indeed there was. The area is known to locals as Judy’s Hole, named after a long-since infilled pit owned by a wise woman, no less.*

Squatters’ cottages opposite Judy’s Hole, c.1920. (Cambridgeshire Collection)

The Fen People

One of the oldest works on my shelf is a charming and very rare book printed in 1930. The title is embossed on its faded red cover, The Fenman’s World, by Charles Lucas, Burwell doctor and former Fen drainage commissioner. Having lived in the village his whole life, some of his friends thought ‘it would be both interesting and useful’ to document his knowledge and memories of the Fen areas at Burwell and its neighbouring villages of Reach and Wicken. The book includes an account of Judy’s Hole and the Fen people who inhabited six wattle-and-daub squatters’ cottages on the opposite side of the river during the nineteenth century.

The men were ‘rather tall and big, with very black hair, sallow and swarthy complexions, rough in their manners, gruff in speech, tenacious and cunning, independent and lawless’. Their secrecy and self-reliance earned them the nickname Fen Tigers. These were people who lived off the land, catching fish and hunting wildfowl for food as well as keeping livestock. In summer, they would help with the harvest, dig turf and cut sedge. The turf they dug was peat, cut into rectangular blocks, dried and burned as fuel. Sedge could be burned too or used to stuff mattresses, but was mostly cut for thatching. Like reed, it is a grass-like plant that grows in wet ground. Reed has hollow, round stems whereas sedge has a triangular stem. ‘Sedges have edges, rushes are round.’

The characteristic species in this part of the Fens is Cladium mariscus, known as saw-sedge because its edges are toothed. Run your fingers upwards along the leaves and the razor-sharp serrations can cut to the bone, each tiny tooth a natural blade. For this reason, harvesting sedge was listed as one of the most horrible rural practices in a television documentary titled The Worst Jobs in History. Arms would be bound with hessian and twine for protection, while sedge was cut manually using a scythe. It would then be tied into bundles, stacked and dried.

Life was hard for the Fen people. In the mid-nineteenth century, ague (a malarial fever) was a problem in the Fens, spread by Anopheline mosquitoes. Most Fen gardens contained a patch of white poppies, used as a remedy for ague. Opium chewing and brandy drinking were ways of relieving fever and easing pain.

On Adventurers’ Fen, a couple of miles east of Burwell, lived Old Tom Harrison, the last Fen ‘slodger’.* He would gather paigles (cowslips and primroses) from the meadows to make wine for relieving the symptoms of ague. Old Tom lived as a hermit in a hut made of turf blocks plastered with clay to make them waterproof. Allegedly, he only ever washed if he fell into a ditch. Payment for the ducks, geese, eels and tench he sold would be made partly in opium.

Following the death of her husband Joseph Finch, Judy also lived alone, in her riverside hut. The 1841 census lists her age as 50, and farmer as her occupation. Lucas describes Judy as ‘a very bad character’ with a ‘vile reputation for dark deeds’. He states ‘if there were any devilry going on in the parish, Judy Finch was sure to be in it’. She was the wise woman of the district and in earlier times would have been considered a witch.

I can’t help but wonder whether her reputation was unfair. Life must have been hard. Maybe her grief was misinterpreted as evil rather than a sign of inward suffering. Perhaps, like the fictional character Elphaba Thropp (the Wicked Witch of the West in the musical Wicked), she was not mean but misunderstood. Judy did, however, contribute something to the village. She sold her 1-acre pit to the Drainage and Navigation Board. It was used to extract thick clay, known as gault, for repairing riverbanks, an ongoing task in the Fens. Judy’s Hole held around 2ft of water, which would freeze in winter, making skating possible.

Fen skating had become very popular by the nineteenth century. Many agricultural labourers would compete in races for prizes of money, food and clothing. Cambridgeshire-born horticulturalist and author Alan Bloom describes the fun of speed skating:

When some of us got together in a string, heads down, arms on backs, watching the ice flash beneath us to the rhythm of long, ringing strides, there was no thought of work or worries for hours on end. Men and youths out of work through the frost would get together and play bandy** on their fen runners.

The Cambridgeshire Fens produced numerous top skaters. But being champion sportsmen did not rid the Fen Tigers from prejudice. Even at the start of the twenty-first century, at The Deepings School, I remember students from Spalding getting teased unkindly for being inbred and supposedly having webbed feet.

Adventurers’ Fen: Wednesday, 3 August 2011

I lock my Volkswagen Fox and head out into the damp, humid evening wearing a crumpled, black waterproof jacket. The buckled concrete of Harrison’s Drove peters out into a grassy track, eventually leading me to the reedbed. Here, I join the Wicken Fen bird ringing group for their dusk mist netting session, fitting birds’ legs with tiny metal rings as part of a long-term scientific study to learn more about their migrations. An otherwise low-key 22nd birthday had been transformed by a chance meeting with one of the bird ringers, Neil, earlier in the day, as recorded in my diary:

It was quite wet when I arrived. Neil was stood in the shed entrance with a hat that made him look like Charlie Gearheart.* The swallows and sand martins dropped into the reeds to roost for the night. An incredible 88 were caught. The clouds of birds made for an atmospheric and timeless evening. It was not without its mosquitoes however, and I was bitten no less than 14 times whilst we were taking the birds out of the mist nets.

This was a little taste of the muggy summer nights that Old Tom Harrison would have known, having lived mere metres from where we were working. Thankfully, these modern mosquitoes did not contain malaria. Surrounded only by reeds and roosting hirundines,** it really did feel timeless, as if the reedbed had been there for centuries. However, just two decades earlier, it did not exist at all. Instead, Adventurers’ Fen contained fields of potatoes, sugar beet and wheat, having been drained for agriculture during the Second World War – following in the footsteps of the Adventurers who had dug the Old Bedford River and drained vast amounts of Cambridgeshire in the mid-seventeenth century.

Ouse Valley: Monday, 14 November 2022 (Part Two)

The sun sinks beneath the horizon, not that it had been visible through the fog. I am wrapped up in my thoughts, enveloped in the strangely comforting fogginess, absorbed in the slow rhythm of my feet, which are now completely wet. Oakley is a few feet ahead, leading the way along the Old Bedford Low Bank in his luminous green collar. Visibility stretches little further than the track on the other side of the river, which has been closed for two years while the Environment Agency raise the height of the bank in defence against flooding. This project involves importing thousands of tonnes of material to protect my home village – and numerous others – from potential flooding predicted as a consequence of climate change.

Oakley on the Old Bedford Low Bank, 14 November 2022. (Ajay Tegala)

The Old and New Bedford Rivers are an impressive feat of engineering by Cornelius Vermuyden of the Netherlands and the fifth Earl of Bedford. The mammoth task of manually canalising a 21-mile stretch of river – and digging a second channel of the same length – was undertaken by the Gentleman Adventurers. These English engineers and landowners funded and undertook the drainage of the Fens. In return, they retained rights to some of the land they reclaimed. But a few of the staunch Fen people were fiercely opposed to the drainage of their prosperous fishing and hunting grounds, especially at Wicken. They did not want to be tamed or controlled. The Adventurers were forced to employ armed guards for safety from the sometimes rough and rowdy Fen Tigers.

King Charles I envisaged building a new city, to be named Charlemont, on the Isle of Manea, a mile west of the Old Bedford River. The foundations of a summer palace were constructed, but the king’s imprisonment, in 1646, halted any further progress. The New Bedford River (also known as the Hundred Foot Drain) was completed in 1651, when a sluice was built at Denver, in west Norfolk, to control flow of water into the Wash and out to sea. Between the Old and New Bedford Rivers, floodwater is diverted into a large washland, half a mile wide. In winter, the Ouse Washes take on water carried by the River Great Ouse from the counties of Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Northamptonshire, creating an important 6,000-acre roosting area for wetland birds including thousands of ducks and whooper swans.

During the construction of the Bedford Rivers, two attempts were also made to drain the fens of Burwell and Wicken. This caused inhabitants of the latter village to riot, determined to protect their fen’s bountiful fish, fowl, fuel, grazing and thatch. The villagers of Wicken made petitions to the Adventurers. As a result, part of Wicken parish, recorded as Sedge Fen since at least 1419, was divided into strips and shared between the commoners. A 10-acre triangle of the adjacent St Edmund’s Fen was made available for the poor of the village.

By sheer coincidence, rather than design, rotational cutting of sedge created an ideal habitat for a diversity of plants and associated insects, preventing the fen from becoming overgrown with bushes and drying out. The East Cambridgeshire Fens had become a prime collecting site for nineteenth-century entomologists. A young Charles Darwin was said to have collected beetles in the east Cambridgeshire Fens* in the 1820s.

Much of Burwell Fen was eventually drained in 1840. But the people of Wicken held firm, continuing to fight against drainage. Their fen had become the sole source of sedge in the county and the only area of semi-natural fenland accessible from Cambridge. In 1894, entomologist James W. Tutt wrote a wonderful account of a visit he made to Wicken Fen:

Attempting to cross a level-looking piece of ground covered with sedge, [I] found myself precipitated at the first step up to my waist in water, and discovered that the smooth-looking ground was a dyke, on which the sedge rested so alluringly.

The Nation’s First Nature Reserve

On Monday, 1 May 1899, The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty (as it was then called), in its fifth year, purchases 2 acres of land on Wicken’s Sedge Fen. It is sold by entomologist J.C. Moberley for the sum of £10. This goes on to become the Trust’s first nature reserve, with banker and early nature conservationist Charles Rothschild donating parts of St Edmund’s and Adventurers’ Fens in 1901. The reserve grows considerably in 1911 when Newmarket-based scientist and politician George Henry Verrall bequests 239 acres to the National Trust. A keen botanist, Verrall had rediscovered multiple plants declared extinct sixty years earlier by the University of Cambridge’s Professor of Botany, Cardale Babington.

In 1914, Wicken man G.W. Barnes is employed as the fen’s first watcher.* His role involves harvesting sedge and the first remedial bush clearance, conserving important invertebrate habitat by preventing the open fen becoming overgrown and drying out (this has been an ong oing battle ever since). A system of permits is implemented to avoid the damaging impact collectors could have on rare species if left unregulated, thus helping to protect the wildlife of this very special fen for future generations.

Well over 9,000 species have been recorded on Wicken Fen between the early nineteenth and early twenty-first centuries, more than any other site in the country (see Appendix 1). These include at least ten species discovered on Wicken Fen that were completely new to science, plus a further twenty-five firsts for Britain. Turn back the clock a couple of thousand years and beavers would have been present (before being hunted to extinction), as indicated by a lower jaw bone found in the peat on adjacent Burwell Fen. Ancient whale bones and shark teeth have also been unearthed, and a 3,000-year-old human skull, as well as prehistoric reptiles from many millions of years ago.

Long before the peat was formed, gault clay was the uppermost stratum and formed the sea floor. In the subtropical seas lived the shark-like ichthyosaurus, the paddle-legged plesiosaurus and above them flew the bat-like pterodactyl. Fossilised bones and excreta of these reptiles are known as coprolites, derived from two Greek words meaning dung and stone. Their discovery on Burwell Fen in 1851 led to large-scale digging, rather like a gold rush. Being rich in phosphates, coprolites were used for the manufacture of fertiliser, superphosphate of lime.

An article published in the London Evening Standard on Saturday, 21 April 1900, paints a splendidly vivid picture of what Wicken Fen was like just a year after the National Trust’s first land acquisition:

Enclosed by broad ditches … it is overgrown with coarse sedge and sallow-bush. Rare plants and rare insects lurk in this natural sanctuary, and make a happy hunting ground for the botanist and entomologist. It has a charm of its own in a sense of indefinite vastness, and nowhere in England are the sunrises and sunsets more glorious, for a whole hemisphere of sky over-arches the place.

But the charm of the Fen is greatest when it is explored minutely. The swallowtail, perhaps the most beautiful of English butterflies, still lingers, though not nearly so common as formerly, when it was less hunted, and the food-plant of its caterpillar grew almost everywhere. Dragonflies dart to and fro like microscopic hummingbirds, the green snake writhes through the herbage, while rare birds still haunt the fens, though not in the abundance of forty years ago. Sometimes, however, a harrier or one of the scarcer hawks may be seen poised overhead. Dunlin, sandpipers, snipe, teal, ducks of various kinds, and in a hard winter wild geese visit the place, possibly even a whooper swan makes its appearance. But the drainage of the fens has gradually driven most of them away from East Anglia.

‘Cock-Up’ Bridge: Sunday, 4 August 2002

My parents’ green Toyota Avensis heads slowly towards Factory Road. I have been a teenager for twenty-four hours and, bizarrely, this is what I am most excited about. Not a video game, not a gadget, not food, but crossing Ash Bridge and going to the end of Factory Road for the first time. Since my mysteriously fascinating experience at Judy’s Hole in the spring, I have been strangely gripped by an intense intrigue relating to the nearby Fens. Travelling along this 1½-mile road fills me with suspense, as if it will lead to somewhere interesting and important.

Partway along, we pass a pylon, right by the side of the road. It seems enormous, part of a long line dominating the landscape. They look futuristic and yet dated at the same time. The progressively greying sky is heavily pregnant with rain. A downpour is imminent.

The drove reaches a T-junction at Priory Farm.* We head left, dipping just below sea level and parking up on what is essentially the edge of Wicken Fen nature reserve. Ahead, a grassy bank is visible. On top of it are two bridges over Burwell Lode, one made of concrete and the other an electric drawbridge held in the upright position. Known to locals as ‘Cock-Up’ Bridge, a manual drawbridge (named High Bridge) had stood on this site from 1848, tipping up to allow barges along the lode and swinging down to let turf-diggers wheel their barrows across. One of three drawbridges in the area, all were replaced with steep-sided, humpback affairs in the early twentieth century. These were also known as ‘cock-up’ bridges, despite being static. Just one of these wooden bridges remains, over Wicken Lode, albeit completely rebuilt in 1995. The bridge near Priory Farm was replaced with the current concrete construction in 1966.