9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The “Joint Declaration of Twenty-two States,” signed in Paris on November 19, 1990 by the Chiefs of State or Government of all the countries which participated in World War Two in Europe, is the closest document we will ever have to a true “peace treaty” concluding World War II in Europe. In his new book, retired United States Ambassador John Maresca, who led the American participation in the negotiations, explains how this document was quietly negotiated following the reunification of Germany and in view of Soviet interest in normalizing their relations with Europe. With the reunification of Germany which had just taken place it was, for the first time since the end of the war, possible to have a formal agreement that the war was over, and the countries concerned were all gathering for a summit-level signing ceremony in Paris. With Gorbachev interested in more positive relations with Europe, and with the formal reunification of Germany, such an agreement was — for the first time — possible. All the leaders coming to the Paris summit had an interest in a formal conclusion to the War, and this gave impetus for the negotiators in Vienna to draft a document intended to normalize relations among them. The Joint Declaration was negotiated carefully, and privately, among the Ambassadors representing the countries which had participated, in one way or another, in World War Two in Europe, and the resulting document -- the “Joint Declaration” — was signed, at the summit level, at the Elysée Palace in Paris. But it was overshadowed at the time by the Treaty on Conventional Forces in Europe — signed at the same signature event — and has remained un-noticed since then. No one could possibly have foreseen that the USSR would be dissolved about one year later, making it impossible to negotiate a more formal treaty to close World War II in Europe. The “Joint Declaration” thus remains the closest document the world will ever see to a formal “Peace Treaty” concluding World War Two in Europe. It was signed by all the Chiefs of State or Government of all the countries which participated in World War II in Europe.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 154

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

“Those who conduct a war are also those

who must agree to end it, for each is master

of his own interests, and only he can dispose

of them.”

Hugo Grotius, The Law of War and Peace

Author’s Note

I would like to express my deep appreciation to my friends at ADA University in Baku, Azerbaijan, for their generous support for this book project. Their support included hosting me as a visiting faculty member for two years, and also direct support for the writing and publication of this book.

My appreciation goes especially to my friends—Rector and Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Ambassador Hafiz Pashayev, and Executive Vice Rector Fariz Ismailzade—as well as all the other faculty members at ADA University, who warmly welcomed me to their beautiful campus.

I am also grateful to the Center for International Security and Arms Control at Stanford University, which published my lectures there in 1995 as the book, “The End of the Cold War is Also Over,” edited by Professors Gail Lapidus and Renee de Nevers.

The Unknown Peace Agreement

How the CSCE Negotiations Produced The Final Peace Agreement with Germany And Concluded World War Two in Europe

FOREWORD

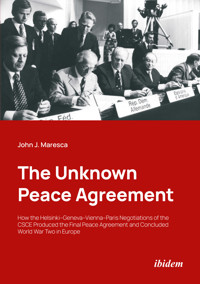

Author’s Comments: The Cover Photo—and the Peace Agreement

Introduction

Chapter 1 The Question of Germany

Chapter 2 Private Discussions

Chapter 3 A Conference to Conclude World War Two in Europe

Chapter 4 Becoming a Key American Negotiator

Chapter 5 Pursuing a Broad-Ranging “Diplomatic” Career

Chapter 6 A Deadly Incident Helps to Bring Safer Military Practices

Chapter 7 The Conference Moves Toward the Summit—and History

Chapter 8 Ensuring that Germany Could Reunite—The Clause on Peaceful Changes of Frontiers

Chapter 9 Brezhnev’s Big Mistake: Popular Agitation Leads to German Reunification

Chapter 10 A Summit Meeting to Conclude the Cold War

Chapter 11 The Baltic States Agitate for Independence

Chapter 12 The Dissolution of the USSR

Chapter 13 Russia’s “Near Abroad”

Chapter 14 Soviet Objectives and the Reality of History

Chapter 15 The Promises We Keep

Chapter 16 The Peace Agreement: The “Joint Declaration of Twenty-two States”

Chapter 17 The Only Peace Agreement

Chapter 18 The USSR is Dissolved

Chapter 19 Ambassador to the “Near Abroad”

Postscript

Annex Timeline for the Author’s Association with the CSCE Negotiating Process

About the Author

FOREWORD

Thirty years ago, an unusual diplomatic document was negotiated in Europe and signed by the Heads of State or Government of all the countries of Europe and North America which had been participants—in one way or another—in World War Two in Europe. The summit-level signature ceremony for this document, called the “Joint Declaration of Twenty-two States,” was held at the Elysée Presidential Palace in Paris on November 19, 1990, sandwiched inconspicuously between the signature ceremonies for two key international agreements of that era—the “Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe,” and the “Charter of Paris for a New Europe.” These two documents garnered all the attention of the moment, signifying a new beginning for security and cooperation among all the States of Europe and North America.

The brief, two-page “Joint Declaration,” signed at the summit level on that occasion, has been overlooked by analysts, historians, and political leaders, but it has its own historic significance, which only became clear later, in light of the events which followed. As is clear from its text, signed by all the Chiefs of State or Government of the countries which participated in the Second World War in Europe, the “Joint Declaration of Twenty-two States” was intended to accomplish two key historical goals: to formally conclude the Second World War in Europe, and at the same time to mark the end of the Cold War which followed, and which was the last chapter in that war. As we can see now, more than twenty years later, this modest “Joint Declaration” did indeed mark these historical turning points, with the signatures of the Chiefs of State or Government of all the States which were belligerents in that war.

Looking back, thirty years later, we can see that there was only a brief moment in time when it was possible to formally agree on such a “Joint Declaration.” The unification of Germany and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union were key historic events that bookended the Declaration; it could only have been agreed—and signed—in that brief interval between two political earthquakes, when the leaders of the states which had participated in the war could assemble together to approve a declaration that would both conclude the past and define the future. To legitimately conclude World War Two in Europe this document had to be signed by the chiefs of state of all the countries which had been belligerent states in that war—in one way or another.

Despite the intervening years since its signature in 1990, much of the World remains oblivious to this unique peace agreement, and to the significance of that event. The Joint Declaration has been relegated to the status of a legal footnote, and its historic importance has not just been misunderstood, but ignored.

Throughout history virtually all wars and major conflicts have been formally terminated with highly visible treaties and agreements. It would be deeply puzzling if there had been no agreed termination for World War Two and its final chapter, the Cold War. How could those historic conflicts simply stop, with the participants just standing down and moving on to other activities?

And indeed, the wartime belligerents did not just walk away from those conflicts—they very specifically agreed that the war was over, and that their countries “were no longer enemies.” This was the agreed purpose, and the historic significance, of the Joint Declaration, as its text makes clear. The Joint Declaration, signed by the Heads of State or Government of all the countries which participated—in one way or another—in World War Two in Europe, clearly constitutes the legal recognition by all the belligerents that these two connected conflicts had, indeed, been formally ended.

Fortunately, a book has now been published which undertakes to correct this major historical oversight. “The Peace Agreement”, written by my longtime Foreign Service colleague and friend of 50 years, Ambassador John Maresca, fills this gap. Ambassador Maresca personally played a key role in the negotiating process which produced this document, over a period of many years, and his book provides a full discussion and analysis of the background and agreed purpose of the Joint Declaration. “The Peace Agreement” recounts the little-known story of how this document came into existence, and demonstrates conclusively that the Joint Declaration not only was intended as a “peace agreement,” but also fulfills the requirements of a peace treaty for both World War Two and its final chapter, which is known as the Cold War.

There were indeed documents signed in 1947 purporting to end World War Two (the “Paris Peace Treaties”), but they failed to achieve the central purpose of a peace agreement since one of the key belligerents—Germany—was absent. In fact, at the time the single, united state of “Germany” did not even exist, having been delegitimized as a sovereign state, and divided, following its wartime defeat and occupation by the victorious wartime Allies. The dictum of Grotius applies here—the states which fight the war must also be the states which agree to end it.

And there were other efforts to find agreement on the final issues after the war. But they did not include all the interested belligerent—and victim—states, and therefore cannot be considered legitimate peace agreements. Until the Joint Declaration was signed in 1990 by all the European World War Two belligerents (including the newly reunified state of Germany and a declining Soviet Union), no document or agreement was signed, and no “peace conference” was held, which legitimately served that purpose.

The uniqueness of the Joint Declaration may actually be one of the fundamental reasons that it has received such short shrift in the twentieth century lexicon of conflict. The brief form and content of the Declaration was simply so novel and modest that its importance was never recognized within the standard historical pattern for bringing conflicts to a close. Furthermore, its successful negotiation allowed its signatories to quietly move on without drawing attention and criticism to the fact that it had taken so many decades to complete the task. And the dissolution of the USSR, about one year after the Joint Declaration was signed, ended any possibility that a more elaborate, more “historic” document might be negotiated at a later date.

But the Joint Declaration is far more than an historical box-checking exercise, something that might have been done solely to correct an oversight. By innocuously combining a legal closure for World War Two in Europe with an international recognition that the Cold War had also ended, the signatories set the stage for the next historical phase of European security relationships. They thus provided the substantive backdrop to the many post-Cold War agreements and arrangements that continue to define the specifics of how the countries of Europe will live together and resolve their disagreements and problems. Without the Joint Declaration, there would have been no unifying philosophical and political context for this historic, evolutionary work.

Ambassador Maresca’s personal story, related in the book, provides a striking and improbable twist to this historic negotiation—a troubling personal story of the impact of war. Born in Italy, raised in the US, educated at Yale and with service as an officer in the US Navy, Maresca tells us how his personal life experience contributed to his success in roping together a disparate group of international negotiators to finalize the text of the Joint Declaration. The book recounts how this was done in a personal way, adding a fascinating and human insight into how a document of such crucial historical importance was forged.

One has to hope that “The Peace Agreement” will receive the attention it deserves, so that many other related documents, treaties and agreements can be more correctly understood and placed in context. Only then will history have been properly served.

John H. King

US Foreign Service Officer (retired)

Author’s Comments:The Cover Photo—and the Peace Agreement

I have always been fascinated by this photo. When it was taken I was sitting just opposite Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, in the seats reserved for the United States representatives, as the Deputy Head of the American Delegation that negotiated the Helsinki Final Act, which Schmidt had just signed on behalf of the Federal Republic of Germany. At the time, many people thought the central significance of the Final Act was that it officially recognized the division of Germany, and thus ensured its permanence. But we negotiators knew that a clause had been introduced in the text which preserved the possibility of “peaceful changes” in frontiers—“by peaceful means and by agreement.” This insertion was to preserve the possibility of eventual German reunification, and—many years later—it served this purpose, permitting, without objection from any quarter, the peaceful reunification of Germany.

Most of us who were involved over many years with the CSCE negotiating process understood that—at its very heart—the CSCE was about Germany; its future, its eventual reunification, and the long road back to its legitimate, historic role as one of the leading nations of Europe. And we insiders” also knew that this vision of Germany’s future depended crucially on that central phrase, deep in the text of the Helsinki Final Act: “Frontiers can be changed, in accordance with international law, by peaceful means and by agreement.”

What is fascinating about this photo is the expression on the Chancellor’s face. He knew, of course, that the possibility of “peaceful changes of frontiers” had been preserved in the Helsinki Final Act, which he had just signed, by that special clause negotiated with the Russians by Henry Kissinger, on behalf of the FRG. But his facial expression seems reflective, almost one of resignation. Was he asking himself whether he had sufficiently ensured eventual German reunification; whether this would be the conclusion of German voters?

He must have wondered how the wording of the Final Act would be analyzed and interpreted in Germany—there were many skeptics at the time, who doubted the importance and the impact of the CSCE. Would the German people understand that the possibility of peaceful reunification had been preserved by the meandering text of the Helsinki Final Act?

There were skeptics everywhere when the Final Act was signed. The Wall Street Journal famously headlined “Gerry, Don’t Go,” appealing publicly to President Gerald Ford not to go to Helsinki to sign the Final Act. But history eventually recorded a very different story. Germany was, indeed, peacefully reunified. The USSR withdrew peacefully from Eastern Europe—and was eventually dissolved. The American presence was dramatically reduced. Europe became a “union,” with many common institutions. There were national adjustments in many places, and changes in many frontiers. And eventually even the Wall Street Journal apologized publicly for its opposition to the Helsinki agreement.

I watched that signature ceremony from the second row of seats in Finlandia Hall, in 1975. The signors were on a low stage, just in front of us, facing the audience. I could have reached out and touched the Chancelor as he signed. He was poker-faced—not a glimmer of emotion. I have often wondered how these leaders viewed the Helsinki Final Act at the time—I expressed this sense of lingering doubt at the end of my first book on the CSCE, called “To Helsinki.”

The CSCE was a monumental negotiating process, and this book reveals its best-kept secret: it was the “peace conference” which formally concluded World War Two in Europe.

***

When the negotiation which produced what was called the “Charter of Paris for a New Europe” began, the negotiators, including myself, were mandated—in very general terms—to produce a document which would recognize that the European situation had moved to a new level of normal, peaceful interstate relations. Everyone involved in this process understood that popular unrest in East Germany, and pressures for change in Eastern Europe, demanded some sort of acknowledgement—that historic changes were needed to meet the historic popular demand for change which was growing dramatically in what was then the German Democratic Republic, and throughout Eastern Europe.

The situation demanded dramatic changes—recognition that World War Two in Europe was over; the end of the division of Germany which had resulted from that war—and broad democratization of the governing systems in Eastern Europe. In this general political environment the initiative was seized by two international leaders—President François Mitterrand of France and President Mikhail Gorbachev of the Soviet Union. Together they called for an all-European summit meeting, to include the USA and Canada, to recognize the new situation and point the way toward a new basis for relations among the States of Europe. They sought a general and historic recognition that the Cold War was over, and that relations among the states of Europe should now return to a more normal situation.

To accomplish this recognition and transition, they reconvened the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe—the “CSCE”—which had in many ways launched the easing of the post-World War Two situation through the all-European negotiations that produced the “Final Act” of Helsinki—and which had the unique advantage of including all the states of Europe and North America. The idea was to join all these states in an official recognition that the Cold War—that final phase of World War Two in Europe—was over. This broad group of states began negotiating on this challenging array of issues in Vienna, where negotiations were already on-going on issues relating to the military confrontation in Europe between the countries of the NATO Alliance and those of the Warsaw Pact.

But mid-way through this new negotiation an unforeseen development took place—the extraordinary surge of popular demand, in the streets of the two German states, for the reunification of the historic state of Germany. This show of the will of the German people was unstoppable, and the wartime allies—the USA, the USSR, Great Brittan and France—moved as quickly as possible to arrange for German reunification. This was accomplished in record time—for such a monumental diplomatic challenge—and Germany was, indeed, reunified.

In this situation the European delegations in the on-going “CSCE” negotiations convened a meeting of the states which had been participants—in one way or another—in World War Two in Europe—all the European states except those which were “neutral” or “non-aligned,” plus the USA and Canada. Realizing that, for the first time since the end of the War, the single state of Germany was present to negotiate a conclusion to that war, they believed that the situation offered a unique opportunity to officially conclude World War Two in Europe. There had already been token efforts to do this, but never with the participation of the full and independent state of Germany, clearly one of the principal participants in that war.

Based on this logic, and without a specific “requesting state,” informal discussions began in Vienna on a document which would be a “peace agreement” among all the states which had been participants—in one way or another—in World War Two in Europe. No participating state objected to this development, and this negotiating process produced—sometime later—the document known as the “Joint Declaration of Twenty-two States.” This document was signed, at the summit level, in Paris, by the Chiefs of State or Government of all these countries, on November 19, 1990. The original signed copy is held by France, as the host country for the signature event.

The “Joint Declaration” is an agreement that World War Two in Europe is over, that the countries which participated in that war are no longer enemies, and that they “extend to each other the hand of friendship.” There can be no doubt about the intention of the countries which signed this document—all the countries which participated, in one way or another, in that war. It was intended—very clearly and very simply—to end the war. It is the sole and unique peace agreement to end World War Two in Europe.

And there will never be any other such agreement, because about a year after the Joint Declaration was signed one of the principal participants in that war—the USSR—was dissolved and ceased to exist, making any further such agreements impossible. The Joint Declaration therefore remains as the Peace Agreement which ended World War Two in Europe.

This book is the story of how the “Joint Declaration of Twenty-Two States” was negotiated.

***