9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Glagoslav Publications B.V. (N)

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

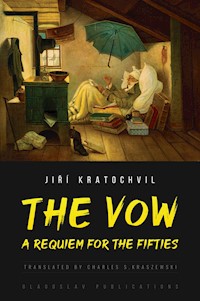

Can something that exists merely as a literary text, say a story, come about in real life? Can reality, to put it another way, steal something from literature, the same way literature steals from reality? Such is the question that Libor Hrach, the author of The Adventures of the Wise Badger, fields one evening over a hedonistic supper in a tony Brno restaurant from Kamil Modráček, himself a burrowing animal of sorts, in Jiří Kratochvil’s novel The Vow.

‘Quite simply, I said, everything that has been written either has already happened, or is about to. You write a story, and you can never be sure if what you’re writing isn’t actually taking place two streets away from where you sit…’ If this does not send chills down the spine of the reader of The Vow, they have got a high tolerance for the creepy.

Set in 1950s Brno, at the height of Gottwald’s Stalinist reshaping of Czechoslovakia into a Communist prison, and partially in today’s independent Czech Republic, Kratochvil, alternating between the dry Czech humour of Jaroslav Hašek and the uncanny, chilling otherworldliness of Edgar Allan Poe, takes the reader on a journey such as they have never been on before: to geographic areas in the beautiful Moravian city where no foot has set since the Middle Ages, and… places deep inside all of us, where most of us would rather never venture…

Translation of this book was supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 548

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Vow

A Requiem for the Fifties

Jiří Kratochvil

Translated byCharles S. Kraszewski

Glagoslav Publications

THE VOW:

A Requiem for the Fifties

by Jiří Kratochvil

Translated from the Czech and introduced by Charles S. Kraszewski

Translation of this book was supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic

First published in the Czech as Slib in 2009

Proofreading by Stephen Dalziel

Copyright © Jiří Kratochvil, 2009

Copyright © Druhé město – Martin Reiner, 2009

Introduction © 2021, Charles S. Kraszewski

Cover art: Carl Spitzweg ‘The Poor Poet’ (1837)

Book cover and layout by Max Mendor

© 2021, Glagoslav Publications

www.glagoslav.com

ISBN: 978-1-914337-57-4 (Ebook)

First published in English by Glagoslav Publications in November 2021

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is in copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This novel is dedicated

to the memory of my mother,

the real person

behind the events described.

Introduction

In the Name of Kamil Modráček? Jiří Kratochvil’s Imperfect God

Tadeusz Kantor once said that one doesn’t enter the theatre with impunity. Ezra Pound said that a book should be like a ball of light in one’s hand. Both these great writers, whose lives were impacted by the horrible events of the mid-twentieth century, a portion of which make up the background to Jiří Kratochvil’s novel The Vow [Slib], imply that those who engage with dramatic or literary art ought to expect to be challenged by the artworks. Texts are not made to entertain, or, at least, not merely to entertain. They are to pose questions to us — sometimes uncomfortable ones. The Vow is just such a challenging work. As such, the questions it asks are many; perhaps as many as there are readers. As a translator, I have been engaged with this book for several years. But it was only very recently, once the translation was completed, that it finally became clear to me what question it was confronting me with. Just in time, as I was about to begin work on this introduction.

It came to me at Mass.

It was a Sunday morning, at a small parish not my own, in upstate New York, near a lake. Before I go any further, I ought to confess that whereas I love the Mass, I loathe sermons. They’re usually overlong, ingratiating, and full of platitudes, repetitive, poorly constructed, and not at all inspiring. Just like introductions, the cynical reader might smirk. Perhaps.1 At any rate, for me, sermons are a waste of time. I’d like to say that this is because I’m a Catholic, not a Protestant, and ‘we Catholics’ or ‘Catholics of my generation’ don’t go to Mass for sermonising, we go for another reason entirely — to be present at the Holy Eucharist, in which God Himself is not symbolically, but actually, present. But while there’s something in that, the real reason is — probably (I’d like to say that this is an occupational hazard, but that would just be another excuse) — the real reason is probably that I’m just a prig, a snob.

Anyway, I almost missed the question entirely because, with what I’ve just admitted, it won’t be a surprise to You, Reader, that I don’t pay much attention to what the priest is saying during his sermon. Sometimes, I’m even lucky enough to drowse (and luckier still if my wife doesn’t notice me drowsing and elbow me awake). But on this particular Sunday, maybe it was because the weather was nice, or the setting was beautiful, or the trip was enjoyable — I was more conscious than usual during that part of the liturgy. The Gospel was taken from Mark (10:46–52) and dealt with Timaeus, the blind man, who called to Christ while the Lord ‘was leaving Jericho:’ ‘Jesus, son of David, have pity on me.’ To His question ‘What do you want me to do for you?’ the blind man replied ‘Master, I want to see.’ The sermon that ensued was just as dull, boring, predictable and pedestrian as all the rest I’ve ever suffered through. Predictably, the priest tossed some bland rhetorical questions out at the congregation, such as ‘What is it that blinds us? What is it that stops us from seeing Christ in our neighbour?’ after which he spooled off onto a digression, the dimensions of which would have sufficed for a sermon of its own, with questions like ‘What takes the place of God in our lives?’ At (long) last, he brought that digression to an end with some groaner of the sort ‘I’ve never seen a Brinks truck follow a hearse to the graveside.’

As I looked about the church that day, it occurred to me: There’s not a single person here who isn’t thinking right now: ‘I’m not blind; no, not me. I see Jesus in everybody. My stomach’s not my God; nothing takes the place of God in my life; I’m not one of those materialistic fools to whom passing things like belongings or money mean anything…’ And what a wonderful world it would be, if all that were actually true. So, this is when the question that Kratochvil’s novel is posing to me, particularly, hit me. Permit me to hold you in suspense about that for a moment, but I will tell you that I was helped on to the answer, almost immediately, by recollections of two quite different writers: St James and Tadeusz Różewicz. But, with your indulgence: of that, a little later.

we’re only human. unfortunately

Kratochvil subtitles his novel ‘A Requiem for the Fifties.’ This has the ring of finality to it; something akin to what John Lennon said in one of his last interviews: ‘Wasn’t the seventies a drag, you know? Well, here we are, let’s make the eighties great because it’s up to us to make what we can of it.’2 There are a lot of such milestones we impose upon history, as if to say: well, now that’s over, and we don’t have to worry about it any more. But although Khrushchev may have denounced Stalin in February 1956, that no more put an end to totalitarianism and government oppression (of all stripes) than George Bush’s ‘Mission Accomplished!’ speech in May 2003 put an end to the troubles besetting the world since 9/11. There are no full-stops or ‘thick lines’ — to use another frequently invoked metaphor — in history, because people do not change. The same human material that gave rise to the problems besetting the characters in Kratochvil’s novel in the 1950s is walking around today, in the clothes that you and I wear, and it’s only a matter of time until it gets this poor suffering planet into more serious trouble. Woes such as Kratochvil describes don’t come about because of something in the air or the water in a given decade, a given place on the map, they come about because of something in you and me and all of our kind, whether we consider them our brothers and sisters or not, whether we’re able to see Christ in them or not. My tradition, after Augustine, understands it as the ‘spiritual syphilis’ that still inclines us to evil, a residue of Original Sin. Depending on what your tradition may be, you may just want to say ‘Man’s a bastard.’ Yep. No argument here — brother. The grime that infects our world doesn’t carry an expiration date. It’ll be around as long as we are.

Kratochvil himself toys with the idea of original sin when he brings in Nabokov’s short story, the Czech translation of which sparks Kamil Modráček’s imagination on how to even the score with the State Security Services (StB) following the death of his sister. In the Russian tale, a family captures a KGB officer, imprisons him in their bathroom after pronouncing a life sentence upon him. And then:

The family […] arrive at the determination that, when he attains an age older than that of his gaolers at present, they will pass him on to their children’s care, and then, perhaps, on and on, to the children of their children — passing him on like an inheritance from generation to generation.

What is this inheritance, but a binding of all future generations to slavery, to an inherited guilt? To say nothing of the fact that, in this fictional world of Nabokov’s, the present family and their descendants are condemned to life imprisonment as well. Obviously, someone has to remain stuck in that apartment as warder and turnkey, as long as the ‘guilty party’ is imprisoned in the bathroom. It is hard for us to imagine the manner in which our debased human nature holds us in thrall; it is hard to get our minds around the great freedom that our first parents enjoyed before the Fall, which St Augustine sums up in the laconic truth: possunt non peccare — ‘They didn’t have to sin.’ But once they made that decision to sin, the toothpaste, to continue with Nabokov’s bathroom metaphor, couldn’t be squeezed back into the tube, and here we are. Thanks a lot, Adam. Way to go, Eve. From Adam and Eve stretches a direct line through Cain to Kamil Modráček to…

At one point in The Vow, Kamil Modráček, the main character (not to say ‘hero’) of the novel, references Dante’s Divine Comedy, ironically casting himself in the role of Virgil, Dante’s guide. The difference is — as he himself notes with a wink — Virgil’s not carrying a hammer to rap someone on the noggin with. ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here’ indeed. Also unlike the magnum opus of the great Florentine, this ‘Virgil’ will not lead us out of Hell and into the blessed region of Purgatory. He might also have quoted Marlowe’s Mephistophiles in reference to The Vow, at that point where the devil appears to Faustus who, when (O, blessed naiveté!) he professes his belief in progress and doubt in the existence of Hell, responds, ‘Why this is Hell, nor am I out of it!’ Given our tendency to evil, however you wish to explain it, which is as inseparable from us as our very flesh and bones, it is in this sense that Sartre’s quip of hell being ‘other people’ is almost correct. Almost, because — again, in this sense — we just need to strike that word ‘other.’ For proof, I will just point to one more sermon, before I’m done: that which Fr Klenovský delivers in his underground church on the text ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ In the end, someone in his congregation (maybe even more than just one of their number), goes ahead and does just that.

In what way is the murder committed in Modráček’s underground ‘cathedral of silence’ — a killing that some try to justify using Caiaphas’ bloody reasoning (it is better ‘that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation perish not’) — any different from the extra-judicial execution of a supposed enemy of the state in the nearby cellars of the Security Services’ building? The answer is: there is no difference at all. In his book, Kratochvil helps no one to any ‘high ground’; some people may be more victimised here than others, but… everyone is a perpetrator.

It would be nice to say that Kratochvil so constructs his novel as to set his characters in extreme situations, where they are forced to make a choice, or make choices, which they later learn from. This is hinted at once, when Ivan Sluka executes Lieutenant Treblík in the cellars of the StB station on Běhounská:

Once again the basement came to your mind, along with the burning match falling along Treblík’s trouser leg, and what was slipping out of it. And how your dick swelled and stiffened right at the moment when you readied yourself to pull the trigger — just as if it, too, wanted to shoot its load into Treblík, and how then you struck your last match so that you could see where you were shooting, and how you then pulled the trigger four times, and how between the first and second shot you heard Treblík cry out softly Mama, mama! before he crumpled along your legs, rustling to the ground, and how you pulled your left shoe out from under his body with a quick jerk. And how immediately, horridly sick to your stomach you became, hurling the contents of your stomach into the darkness, probably onto Treblík lying there at your feet. My God, you whispered through your sour and sticky lips, I’ve just killed a man. But then you got a grip on yourself, left the scene of your deed, and emerged from the cellar over those endless steps.

But Kratochvil is too good a writer to write so predictable a story. As we shall see, there are various narrators in the complex novel The Vow, and here it is significant that Sluka’s thoughts are not being reported in the usual third-person omniscient voice; rather, we have here a sort of legal protocol. The paragraph above sounds like a prosecutor’s summation, rehearsing the facts to the guilty party. But — no verdict is pronounced, no jury votes, and after this undeniably dramatic moment, Sluka will disappear from our purview. Of great importance here is how even Sluka’s conscience seems to abandon its role as Fury; or, more precisely, is overcome, shrugged off the perpetrator’s shoulder, as soon as he ‘gets a grip on himself and leaves the scene of his deed.’ For — and this is the great strength of Kratochvil’s writing — it is not the fictional characters who are being challenged; we are not being invited to sit on the jury here. No, it is us who will be in the dock.

But more of that, later. To return to the characters in the novel, it is for this reason, among others, we hesitate to call Kamil Modráček, or anyone else in The Vow,a ‘hero.’ Jiří Kratochvil’s Vow is a multi-layered narrative of some thirty-one chapters. Although not every character in the work is afforded the chance to narrate a chapter, various parts of the story are told from different perspectives (although it very infrequently occurs that the same event is shown from different angles). A third-person, omniscient narrator leads us through a full third of these chapters; next comes Modráček himself, who presents nearly that many, for eight are given over to him to narrate. The private eye / SNB second lieutenant Dan Kočí’s voice dominates four, and then Modráček’s sister, and various other main characters (Fr Klenovský is an exception) are given one chapter each. However, there is no real difference between any of these voices. No one among them — not even, perhaps, the omniscient third-person narrator — is a moral paragon. The amount of space, so to speak, that Kratochvil allows his narrators is not intended to direct us to any conclusions about who is more worthy of our respect or our attention. To speak merely of the characters who figure in the main trunk of the book, the chapters dealing with the 1950s, the quantitative ranking has nothing to do with justice, but rather — the amount of naked power the given character wields over others.

power, and fate

The Vow displays the manner in which the fates of people are strongly influenced, if not determined, by forces beyond their control. Again, 1950s Czechoslovakia is a convenient background, against which matters of free will and compulsion can be shown in high relief. However, this is only a vehicle to confront us with our own situations. To what degree are we free in our decision making? What is it that compels us to this, rather than that, decision? Is it fear, or hope of gain, or a determination to do what we know is right, even if it hurts? In Kratochvil’s novel, it is fair to say that just about every one of the characters seems to be in control of his or her fate, only to have their control proved an illusion, sooner or later. We’ve already given the starkest example of this in that self-assured true believer Ivan Sluka, who is in control, not only of his own fate (he decides to take his turns at the twelve-hour night shifts at the station, which he has instituted, to be a good example to his men) but also of another man’s life (the presumed guilty Lieutenant Treblík), only to find that, after executing him — without anger or hatred, but ‘for the good of the working class’ — something changes deep inside him and he cannot function properly anymore. In the aftermath of a drastic, but well-considered action, he is by turns gripped by catatonia and vomiting; his mind itself is completely clouded over (he undertakes a midnight journey to a home he no longer lives in, to visit parents that no longer exist).

And everyone answers to someone; power devours us all. Given the historical setting of the novel, the height of Stalinism/Gottwaldism in 1950s Czechoslovakia, the ‘power’ that compels most of the characters is that of the State, in the person of its instruments Ivan Sluka and Lieutenant Láska. This introduces the theme of compulsion to collaborate (something which we, naively perhaps, feel sealed off safely from by those illusory temporal milestones of ours!). At the start of the novel, Modráček seems a stock character from anti-totalitarian narratives centring on the victims of Nazi or Communist exploitation. He is a victim, and the justification for his collaboration with SS Gruppenführer Wagenheim on the construction of his macabrely-shaped villa in Brno is an understandable one — if not to say ‘noble.’ He wishes to spare the life of his sister:

I was ready to declare myself Albert Speer if it would only buy me some more time to talk with him, to keep trying to fight for my sister’s life. So I risked it and just clenched my jaw and said, You’re looking to build something? I can build anything, from a doghouse to an opera to a hockey rink.

This same desire motivates his willingness to collaborate with the Communist security forces who have taken over from the Gestapo after the war:

As soon as I found myself outside it occurred to me that I should have stressed how I was simply bursting with desire to collaborate, sure, to the very separation of soul from body, anything to convince them that into the care of such a comrade they could safely entrust his little sister; that it was unnecessary for them to hold her any longer in some dark and cold cell.

And so, Kamil Modráček is a cringing doormat during the Nazi occupation of his city, and following its ‘liberation’ by the Soviets. As Ladislava Galusková puts it (though perhaps a bit harshly), he ‘navigates the régimes swimmingly without a single pang of conscience.’3 He will design a villa for a Gestapo officer in the early forties; less than ten years later he will participate in the metaphorical destruction of the family across the hall from him by agreeing to be a snitch for the StB. Is this enduring trait of his — grovelling sycophancy — a flaw in him, a weak human being, or the rational practicality of a man who has but one move out of checkmate? It is, presumably, easier to stick to one’s morals like a self-assured Antigone, usque ad sanguinem, when the only thing the martyr has to lose is his life. But when the gun, so to speak, is pointed at the head of someone we love? ‘Modráček fell victim to a hectic frenzy, such as he’d never before experienced all his life long. Even though he knew that he liked his sister very much, that he was really attached to her, he never imagined just how fatal a force in his life this sibling love was.’ Unlike Winston Smith, the hero of George Orwell’s much darker 1984, who begins screaming ‘Do it to Julia! Do it to Julia!’ when he is faced with torment, so as to spare himself, there is something (again, it is difficult to use the adjective ‘noble’ here), admirable in Modráček’s willingness to sell his soul to at least have the chance to save that of his sister. Considering the atmosphere of the entirety of the main, 1950s, portion of the novel, the second possibility mentioned above seems more suitable to Modráček’s situation. For Kratochvil shows us that oppression is a food chain; there is always someone above you, and someone in turn above him. Or, it is an ouroboros: no part of the serpent’s body is safe, when the head is swallowing its own tail. Rudolf Švarcšnupf, alias Lieutenant Láska, must watch his own step:

Švarcšnupf, Švarcšnupf, the chief was asking for you before he left.

What did you tell him?

That the devil only knows where you’ve been running about.

But you knew I had an interrogation! And the interrogated party was a stubborn cuss — and this drew the investigation out enormously!

Enormously! Chovanec laughed. Where’d you get that one from, enormously! That’s a beaut, that is! Just be careful — that’s not an imperialistic term, is it?

As we said above, no one is exempt from blame. Even as positive a character as Dan Kočí, as far as anyone may be said to have ‘positive’ characteristics in a novel so pessimistic about mankind as The Vow, exploits whomever is in his power:

Just the same was he cheered by the realisation that, at last, he would be using his Leica again, and without having to respect the persons of his subjects overmuch. On the contrary — he was again being empowered to shamelessly strip them to their underclothes in an attempt to eternise them inflagranti, after which, in his darkroom, he would see what intimate details would emerge from the developing pans, captured by his camera… and perhaps he would play with those intimate details under the enlarger… (The private eye had his own private collection of intimate details, worked up by the enlarger. Should anyone take those large format obscenities in hand, they’d never guess that he was glomming at a stable of prominent, highly placed promiscuous mares.)

What is Dan Kočí’s private collection of smut if not his own way of using people, no less repulsive for its ‘virtual’ nature (the camera ‘capturing’ his victims at their most vulnerable moments) as Modráček’s underground ‘city’? In another place, we read of him, setting off on a case: ‘Ants began to crawl all over his back — something he only felt these days right before bedding a heretofore inaccessible partner, whom he’d had to chase after for a long time.’ So, no matter what Dan suggests about his ‘professional ethics,’ the connection he makes between the stimulation provided by his investigation and sexual arousal suggests that he is little more than the classical idea of a pornographer, or addict to pornography, who sees not the whole person in his photos, but only body parts. What is more, Dan’s self-description is just as predatory as any Kamil Modráček prowling the streets of Brno with a rag and bottle of chloroform in his breast-pocket; he too is a ‘hunter.’

whose fault? / whose but his alone?

ingrate. mate in two

If this is the case — dog eat dog eat dog — perhaps everyone is inculpable? Perhaps the world is nothing but an inimical corrosive soup, in which we thrash about, without any hope of reaching shore? Does Modráček speak for us, when, at a particularly nerve-wracking crossroads, he exclaims: ‘What was I thinking, after all? That I’d be able to cheat fate?!’

At times, the world presented by Jiří Kratochvil in The Vow seems a trap. The story of Konečný the builder, who controls Modráček for an entire week, and from afar, like some tantalising god, might be offered in evidence of this fact. His mind is that of a chess-master, always at least one step ahead of his opponent:

Konečný led me over to one of the empty tables. He set up Nabokov’s mate-in-two, and after a short pause, which he evidently relished, he stretched out his hand, set it on the white bishop, and moved it to C2. Careful! I wanted to call out, but the builder, who even heard my unexpressed cry of alarm, immediately showed me how marvellous a move it was, and what resulted from it. […] See? smiled Konečný the builder, and then, with a tiny flick of his finger, he executed the king as if beneath a tiny guillotine. Then he said that he was very sorry, but that the painting would not be changing hands.

I understood then that he had known all along that I hadn’t the slimmest chance of lighting upon that solution, and that he wasn’t taking the slightest risk of losing his Le Corbusier.

Then, in the game of his life, as he attempts to cross the ‘green border’ into the free West, lugging his valuable painting with him, he is ‘checkmated’ at the border, and falls under a hail of bullets just as surely as he flicked over the king with his finger.

The story of the builder and the ‘Russian Roulette’ game with the Le Corbusier is one of the many digressions to be found in this stromata of a novel. At first, it seems to be merely a fleshing-out of Modráček’s character, the introduction of something into his life that would provide it with a ballast of human interest (he loves something other than his sister), something that could give his cringing life a direction, as he puts it: ‘I don’t just admire Le Corbusier, immensely; for me, he’s something of a saint. And with him in my atelier, I’d be ashamed to commit those indecencies of mine before his eyes, that mass production of architectural dwarves. For such magical values a person is willing to pay any price.’ But when we come to the end of the story, and see how it ends, finally and dramatically, for Konečný, the game of chess expands into a metaphor of life, free will, inescapable destiny. The world, it seems, is a prison — Alžběta Hajná, one of Modráček’s ‘tenants’ describes the ‘subterranean horizontal city’ in which she is imprisoned as a ‘delightful Alcatraz.’ Perhaps the story of builder Konečný (whose last name suggests ‘finality’ in Czech, and as koniecność in the kindred language of Polish, ’necessity’) is meant to teach us that, even if you scale down the drainpipe and make it down to the shore of the bay, the currents are too strong, you’ll never make it to freedom?

Cages and imprisonment are a constant Leitmotiv in Kratochvil’s Vow. The bear-cage, with which Modráček (unintentionally) initiates the construction of his ‘delightful Alcatraz’ is introduced right after the circus investigation with ‘electric Belinda,’ whom Dan Kočí tracks down on an adulterous bed in the middle of the big top, with a fierce tiger circling about to ward off intruders. And here we have another marvellous, and marvellously subtle, metaphor. This is as much enjoyment and freedom as we can hope for: lovemaking in a tightly constrained space, sex in a tiger’s cage. We will perhaps call this metaphor to mind in the later parts of the novel, when Luděk explains to his lover Petra: ‘at the time, for our folk sex was the only available route to freedom that the puritanical comrades (and their street gangs) weren’t able to control.’ Alas, as enjoyable a freedom as it may be, it was also an illusory one; sex leads to children; the hooking up of Mrs Modráčková and Láska, both imprisoned in her husband’s ‘underground Utopia,’ leads to the birth of little Eduard Láska. And while, in his benign insanity, Modráčk announces to his prisoners, as Hajná puts it, that ‘we should take the birth of our first child as a joyful sign that we have accepted our new tasks as passengers on Noah’s Ark’ — as a kind of underground Virginia Dare — it is Fr Klenovský, the only character in the novel who represents a world-view that rejects predetermination, who protests:

even though you provide for us in this reality here, the fact remains that we are in a prison, which is, let us assume, merely one pocket in the straitjacket of that much greater prison, into which the entire Czech nation has been thrust, but we needn’t understand a prison within a prison as some sort of enclave of freedom, […and] even if, like it or not, we were to accept the fact that we ourselves are to spend a certain amount of time here, that doesn’t mean that you have the right to imprison children as well, you cannot justify such an act in any way.

These words should be understood in a broader manner than just as the particular situation intimates. The idea of a good, loving God, who loves man so much as even to refuse to impede his freely-willed choices, even when they are harmful (and thus we begin this segment with a citation from Milton’s Paradise Lost III: 96-97) is incompatible with the idea of any sort of acquiescence to the evil determinism that would condone the propagation of children into a prison — this particular one, governed by Modráček, or the wider one, governed (seemingly) by Calvinist-Hegelian-Marxist historical necessity.

The voice of Fr Klenovský, especially here, is one of the most important, if not the most important, in The Vow. This despite the fact that all evidence seems to point to the contrary; we constantly find ourselves in the environment of power and imprisonment. The novel moves from ‘legal’ constraint (Modráček at the beck and call of Láska) through his sister’s imprisonment, to Kočí’s circus investigation and cages both literal and figurative (the bear and tiger cages, Kočí’s Leica), to the purchase of the bear cage, the virtual imprisonment of Láska, and then Modráček’s collection of people in his underground city beginning with Láska himself. Finally, we have (as Fr Klenovský points out) the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) as an inescapable prison (since both Konečný’s and Modráček’s escapes are foiled)… It would be reasonable to assume that the universe is being described here as God’s toy box, and human history the story of the compulsion He exerts on us, no less irresistible as the will of the chess-master who takes a pawn in hand.

Even ignorance is its own form of prison. Consider the story Anička Fraccaroli, Láska’s daughter, relates to Petr Luňák during their interview:

Supposedly, Dad reported that the entire case against the architect’s sister had been fabricated, and he kept on insisting that this was murder, categorically demanding an investigation. He was taken off the case, and a few days later he vanished completely. So, it’s all quite clear, isn’t it? A word to the wise suffices.

She has no idea that it wasn’t the StB who did her Dad in, but the architect. There is no one to explain the truth to her now, and so she — this is important — is constructing an image of the world that has very little to do with the actual truth, no matter how convincing it seems. Remember Fr Klenovský’s objection! In a very similar way, Modráček himself is incarcerated in the prison of ignorance:

I went down into the cellar every morning and evening, in order to satisfy the ever more ravenous Lieutenant Láska. It seemed as if he had decided to compensate for what had befallen him by a fantastic gluttony. And to punish me for having imprisoned him by devouring all of my grain and meat stores. I still couldn’t quite figure out whether or not something had happened to his brain, or whether it was all a trick with which he was assailing my compassion and polite upbringing. Some days he said nothing at all, while on others he babbled on endearingly before falling into some quite incomprehensible tongue.

In exactly the same way — if what Fraccaroli tells us is true — Modráček serves out his own life sentence of ignorance, never coming to know the truth of his sister’s death, which he might have learned that very moment that Láska, by chance, rushed into the foyer of his building to escape the pounding rain. Modráček never gave him the chance, thwacking him on his noggin with the hammer, twice, having prejudged a case without being in possession of all of the evidence.

A similar case is that presented by Dr Pešek. This is all the more eloquent as possible evidence of predetermination than the foregoing. For Pešek is not going to be metaphorically imprisoned by ignorance, he is going to become Modráček’s second victim, imprisoned in the underground after stumbling by chance upon the architect at work constructing his prison in the mediaeval vault. In what is perhaps the one passage of dry Czech humour in a basically sombre book, Pešek’s imprisonment at Modráček’s hands is directly caused by the actions he takes to avoid being imprisoned by the authorities!

And so, still barefoot,I’m walking around the flat, near the glass-paned bookshelves when my good guardian angel turns my head in that direction and — what do I see but — horror of horrors! Masaryk’s World Revolution, the Black Band of that émigré Hostovský, Beneš’s Memoirs and all the books from the Anglo-American Bookstore. What, as if I didn’t know how Venhoda flits his eyes about? I don’t know that just one book of that sort could turn my life upside-down, and after Venhoda’s visit, the next guests to show up at my door might be some SNB goons, just as it happened at the Kratochvils? No, I definitely can’t play around with that. And so I immediately set my hand to the task.

Had he not overreacted to the impending visit of a Communist official who was to drop into his flat the next day, he would have never pulled those books off his shelf, never gone down into the building’s basement at midnight. ‘I had no wish to be part of the idiotic vacuum,’ states Dan Kočí when he comes upon his friend Radek staring blankly into the distance. And yet that’s exactly how he’ll end up too, swallowed by the vacuum along with Pešek who preceded him there, when he goes off cockily, without backup, after Lieutenant Láska.

The fact that it is Fr Klenovský who is proven right in the end, and not the determinists (of Calvinist or Marxist stripe) is borne out by the manner in which time is dealt with in The Vow. For although primarily set in the 1950s, a significant portion of the novel takes place in the 2000s, when we are with Luděk and Petra, who discuss the deeds of Modráček and other amateur turnkeys from the distance of our own day and age, and — this is most important — at least a full two decades after the Velvet Revolution saw the prison walls around Brno and the entire ČSSR come tumbling down. So again, Fr Klenovský’s urging of his fellow prisoners to be patient, for ‘in two or three days they’d be free anyway,’ has an eloquence that exceeds the particular situation in which the words are uttered. In the large sense, they are eloquent of a faith and hope that were proven true in the end: not only was Modráček’s prison door to be opened, but the ‘Communist Utopia’ up above was fated to disappear. And, in a still larger sense, the manner in which time is handled in The Vow, which brings in the free Czech Republic of the twenty-first century as the Communist prison that was Czechoslovakia in the fifties, testifies to change, to progress. Determinism is a prison, because it excludes change, it is a continuum. No child should ever be born into that, and, as history and Fr Klenovský prove, no child is.

Another proof against determinism is provided by Modráček himself. Although (as we will see) he feels himself to be ‘moved’ to his mission by a power outside of himself, the truth is that he takes all of these aberrant decisions himself. And why? He feels trapped, and he wishes to take control, to act out in some way against the horrid chains that seem to bind him.

Consider, for example, the aftermath of his sister’s death, once the initial numbness has passed, and he begins to busy himself with the disposal of her body. Although ‘neither he nor his sister were believers’ in the Christian God, Modráček arranges a ‘funeral Mass and Catholic burial ceremony’ for her, because — he ‘felt that he had to do something.’ It is this feeling of being obliged to ‘do something,’ perhaps anything, that is at the root of Modráček’s insanity, and is to be blamed for the harm he inflicts on other people. For it is not ‘something’ that we need to do, in order to ‘somehow transcend everything that had happened’ — which in this case and all others is selfish self-therapy, something that we need — but the right thing that must be done, to help others. The former attitude is inward thrusting, the latter, outward. And, as another positive character in the book, the physician Dr Štefl well knows — first, and above all, do no harm. When we don’t know what is the right thing to do, when others come into the equation, it might just be better to do nothing at all, even if that means that we must live with our own helplessness. It is better not to help ourselves, than to harm others.

Here, perhaps, it might be fitting to introduce one of those writers who helped me to an understanding of the question posed by Kratochvil’s The Vow just the other day at Mass (as I continue in this question to put the cart before the horse). In his long poem Recycling, Tadeusz Różewicz poses the rhetorical question:

Skąd się bierze zło?

jak to skąd

z człowieka

zawsze z człowieka

i tylko z człowieka4

[Where does evil come from? / what do you mean where // from man / always from man / and only from man]

And Różewicz, whose entire postwar poetic career can be read as a long polemic with God concerning justice, agrees at least so far with traditional Christianity. It’s as simple as that.

kamil modráček, the puny god

Of course, if Modráček were wise, or sane, enough to realise this, we would have no novel. And so, now let us turn to this most important figure of all, in more depth. For, above, all, it is Modráček who is at the centre of The Vow. It is the vow he made to his sister — however meritorious or lacking in merit that vow may be, however reasonable or insane — that is the motor to the entire story, and it is he who deserves most of our attention in a discussion of a novel so deep — no pun intended — that a discussion of all of its characters and motifs would require a book of its own.

Kamil Modráček is a loner. He is estranged from his wife, he has no friends to speak of, his sister (in whom he has perhaps an unhealthy interest) is taken away from him by Láska, and that one constant relationship of his life, which he shares with his ‘invisible wife,’ can hardly be called a human relationship of love. And so his creation of the underground city can be understood as a desperate attempt to collect a group of people who will love him, for they must. He is not just Noah with his ark, he is a morally ambiguous ‘god’ trying to create an Eden where there will be no fall, where he might walk in the garden in friendship with his creatures. Of course, this is naive, to say the least. For he is not God, to Whom man owes obedience and love and gratitude for His having brought him to life; no, Modráček is more or less a puny, negative image of God — he created no one’s life, he ended the lives of twenty-one persons, as far as any of them could tell, by stealing them from the lives they led aboveground, with people whom they loved, to lock them up in a mediaeval vault deep underground. Where God intends freedom, Modráček imprisons, enslaves (they were, after all, forced to help him in the construction of his subterranean opus). So his dream for a little paradise may not be crazy as much as childish, or crazy in an innocent way: the very wrongest realisation of childhood longings for a peaceful world of friendship and harmony. That it had no chance of being realised is something that he himself perhaps sensed. As he is about to leave them for good, their ordeal nearly over, he wishes to bid them farewell:

Turning around, standing face to face with the half-circle that the people now formed, he assayed a friendly smile. But that smile didn’t quite work. He had sensed that this farewell of his with them wouldn’t be worth much, but he had no idea that it would actually be impossible. Right now, he wanted to say something, but his tongue cleft to the roof of his mouth and — why not admit it? — his chin nearly trembled. But on their faces, there was no movement whatsoever.

Well, maybe he is a little crazy. After all, he was stunned at the manner in which ‘somehow none of [them] were taken with the thought,’ when, in apricot season, he offered to cart down bushels of the fruit so that twenty-one adults might ‘make preserves until [they] keeled over!’ Váša the lifeguard from the Zábrdovice baths puts his finger right on it when he snaps, ‘What, when you were a little boy, did you experience a big apricot boil at your grandmama’s and now you want to spread the joy among us?’ Certainly, one definition of insanity is to be so overcome with your own idée fixe that you are literally unable to understand the effect that your actions have on another person; how any ‘reasonable’ person might be unable to comprehend the logic of your progress, or how, really, you have your victim’s best interests in mind. It is for this reason that, as innocent as the apricot boil idea seems to be, we cannot have sympathy for Modráček. A good portion of his insanity certainly is his lack of empathy for others. Consider, for example, what he says about his appropriation of and use of the gold and jewels left behind in the cavern by its previous inhabitants, whether Germans or Jews, or Germans secreting the wealth robbed from the Jews of Brno during the long night of the Holocaust. Modráček has a tinge of conscience at so liquidating the wealth of others for his own benefit, but he rationalises his behaviour immediately:

For that reason I can perhaps consider my discovery an inheritance from those who had to abandon everything when they tried to find some path, some way, to remain at least a little alive. And after all, I hadn’t broken into this mediaeval vault, this their underground place of refuge, by force, like some burglar. No, I’d pierced into it by pure accident, during that wild frenzy of mine, which perhaps they themselves would be able to understand, just like all outcasts and outlaws who fight back against institutionalised hatred in explosions of helpless rage.

Yet, in reference to his own ‘tenants,’ he doesn’t understand that for them he is a hated institution, which projects, if not an institutionalised hatred, at least an institutionalised unconcern with their wills and rights. Modráček’s lack of empathy is actually infuriating. During the apricot-boil episode, he says to his prisoners with a smile: ‘All you need do is ask […] just tell me what you need and I’ll bring it all down here for you, I’d be delighted to.’ What they need? They need their freedom. But that can’t be ‘brought down here,’ and so it’s out of the question.

Modráček’s obtuseness is, or has become, a pronounced trait of his character. He — like we all — has a healthy terror of prisons, something that is made clear when he describes his attempts at tracking down his sister after her arrest by the StB. Stonewalled by everyone he queries as to her whereabouts:

Modráček wanted to try his luck in the prisons of Brno, as well. But the mere sight of those huge, gloomy edifices filled him with terror. He’d never before considered how deeply prison architecture might depress a person: the whole intention of which was not to include in its design anything slightly uplifting or aesthetic, but to create a dead monolith of spiritual emptiness!

How strongly these words strike us when we recall that, whatever he choose to call his ‘subterranean horizontal city,’ it’s still a prison, and the people who populate it didn’t volunteer for residence there — he literally plucked them from the street and incarcerated them within it. His childish regard for his ‘tenants’ or ‘lodgers’ as he calls them can be disarming — as Alžběta Hajná reports: ‘Mr Architect indulged us with a little grass down here and some shrubs, even tulip beds, just about everything that can bear this hothouse regimen of ours without sky and much space,’ but the fact remains: no matter how pleasant you make it, a prison is still a prison. And, as Hajná — happy enough to be incarcerated alongside Dan Kočí (again: sex in a cage) — develops her thought: ‘but beneath this low cavern vault some days I feel that I’d be happy to trade Dan Kočí for a walk lined with chestnut trees or a gigantic kingly walnut or an even grander holm-oak of the sort I used to go visit in Lužánky.’

Another characteristic of insanity, I reckon, is the inability to understand, or accept, the fact of one’s guilt, the inability to accept responsibility for one’s actions, the blame for which one is quite happy to lay at someone else’s feet. Inthe case ofmad Kamil Modráček, he uses the same tropes of predestination which we’ve already debunked to exculpate himself from responsibility for something he knows, deep down, is wrong, convinced that he is under the influence of some will other than his own. He describes his extraction of his father’s manuscript thus:

One evening upon returning home I pulled out a large packet of my father’s unpublished writings from behind some books on the bookshelves. To the very last moment, I had no idea why I was doing what I was doing; what was inducing me to ferret through those old papers at that very moment.

We will pass over the fact that nothing in the scene prepares us for a suggestion of supernatural agency here; this is not Dante’s son having a prophetic dream about the location of the missing ‘heavenly’ cantos of the Paradiso. But Modráček is convinced that he is somehow being ‘led’ to the actions he undertakes. To give just two more examples, from among many, when he discovers the forgotten poster of the SNB operative, the destruction of which will reveal to him the fateful undergrounds of Brno, he says: ‘Nearby, a pickaxe was lying on top of a large box, just as if someone had placed it there for me,’ and later, after the discovery had been made: ‘I knew that that mediaeval vault had revealed itself to me at precisely the right moment; that someone had carefully prepared it for me, just as I had been led to those bookshelves and induced to rummage through the writings my father had left behind.’

No. All of this is nothing but an attempt at rationalising actions which, deep within him, he knows to be wrong. If one is merely the instrument of a higher power (passing over, for the sake of argument, the rightfully discredited Nuremberg Defence), who is to blame for the evil one commits? There may be some tenuous, and perhaps none too convincing, yet all the same comprehensible reasons for his decision to pronounce a sentence upon the head of the person he blames for the death of his sister, but is there any excuse for the composition of his human menagerie? As explained, from a distance, by Luděk, the contemporary student of Russian philology whose interest in Modráček’s history seems something of an obsession itself:

In the end, Modráček understood it all as a vocation, a mission. On the one hand, he kept the promise he had made to his dead sister, his vow to snatch her murderer and punish him with a sentence of life imprisonment, while on the other, by a chance set of circumstances, and random motivations, he broadened that mission of his by degrees: to preserve some sort of pattern of humanity from that which threatened them up above.

This is a megalomania bordering on a god-complex, which (as my entry for the understatement of the year award), I will state is a rather problematical attitude. If we are looking for proof of anyone’s insanity, this sort of thing is fairly convincing.

But if Modráček is a ‘god,’ is he a just god? The very fact of his imprisoning people who have done him no harm is evidence enough of his injustice. Even stronger evidence against him is presented by his initial motivation to impose his (punitive) will on another human being. At first glance, the motivation to take vengeance upon a criminal who is otherwise untouchable seems rational. It is, after all, the common theme of the great majority of black-and-white-hatted Hollywood vengeance trash. It is so understandable as to be almost syllogistic: a) Lieutenant Láska’s role in my sister’s death deserves to be punished. b) The apparatus of ‘justice’ in this country protects criminals such as Lieutenant Láska, so he will not be punished by the proper authorities. c) Therefore, I shall punish Lieutenant Láska myself. Or, as Modráček puts it: ‘Láska must meet with a just punishment, such as refers to a higher justice, far removed from that of the inhuman Communist regime.’ The problem with this is not only that Modráček is neither God nor cognisant of God’s will in this matter, but that vengeance is not justice. Furthermore, there is the matter — not unconnected with the fact of Kamil Modráček’s being far from omniscient — of Lieutenant Láska’s humanity:

Where’s Anička?

Playing outside in the courtyard, Marta answered. That’s not an answer to make Láska very happy. The courtyard in question was full of garbage cans and rotting mattresses, rusted and hole-riddled metal pots. Rats ran about there, and at nighttime drunks would piss down into it from the gallery running outside their doors. Láska fears for his daughter with a tormenting fear. Sometimes, during an interrogation, he’d grow suddenly still. His gaze would drift until his eyes came to rest somewhere, up on the ceiling, let’s say… Once it even so happened that Láska’s victim had to clear his throat once, twice, to jog the Lieutenant back into the present moment, so as to get on with the interrogation.

Láska’s love for his daughter and his need to protect her is a perfect thematic rhyme for Modráček’s love for his sister. By depriving Anička of her father for having first deprived him of his sister (even if this were true), Modráček is not acting justly — the strict ‘eye for an eye’ justice has been abrogated over two thousand years ago. To lift the matter out of the context of Judeo-Christian theology altogether, simply and philosophically put, one cannot set right one immoral action by perpetrating another action that is just as immoral. The two actions cancel each another out, as far as the balance of morality is concerned, and all parties are left with empty hands. Petra James’ words concerning the subtitle of The Vow are worth remembering here:

The book is thus conceived by the author as a requiem for the victims of the Stalinist era of 1950s Czechoslovakia, represented in Kratochvil’s text by his mother (herself a victim of the communist persecution to whom the book is dedicated and who appears as a minor character in the novel), Modráček’s sister, and the policeman Láska, unjustly imprisoned and punished.5

If Kamil Modráček is a god, he is one of those very unsatisfying ones we come across in our pre-Christian culture. As we know, the gods of the Greek and Roman pantheons were different from us in one thing, and one thing only: they were immortal. This in itself is problematical, and cuts right at the root of any sympathy we may have for Modráček’s situation, and how he deals with it. The Greeks, like Homer and Sophocles, seem to have accepted the sort of gods their culture presented them with in fearful reverence, if not, at least, with a shrug. Virgil, closer to our time, has a heart like ours. He wants his gods to be just; he wants them to be the incarnation of impartial justice, of goodness, but — his mythology will not let him. As close as he gets to shaking his fist at an incomprehensibly shoddy Olympus is in his Aeneid, where, upon painting the perfect portrait of the evil, arbitrary god in Juno, who, although she knows that she cannot forestall the founding of Rome, kicks and scratches all the way, sacrificing entire nations of people — even those she supposedly favours, like Dido and Turnus — to her pride, gasps, Tantaene animis caelestibus irae? [Can such anger reside in breasts divine?, I.11]. Modráček is such a petty ‘god.’ He has nothing but power. A chilling hint of this is given earlier on in the work, in the words that Modráček directs at Lieutenant Láska during the first of the interrogation sessions that we witness. He is discussing the manner in which the Germans understood the word ‘work’:

They had a completely different understanding of the word ‘work,’ just as they had in the case of a whole bunch of other words. After all, you’re quite aware that above the gates of the concentration camps they placed the words Arbeit macht frei.

In the context in which we find these comments, we take them to be sarcastic, a pinch of biting back at the hand wielding the whip, the iota of snarky rebellion that the powerless victim feels himself enabled to indulge in. And so does Láska interpret them: ‘You want to lecture me now?’ Later on, however, toward the end of the book, when Luděk and Petra are discussing the matter with the (chillingly) cold interest that makes documentaries about murderers so riveting (and which itself says a lot about our human nature), the words take on a completely different meaning:

Now, I still don’t understand how he was able to keep control of those twenty-one lodgers — why they didn’t rise up in revolt against him.

By force, obviously. Every Utopia is a concentration camp. […] Let us not forget that, among the items he had discovered in that subterranean German hodge-podge there were also two pistols: a 7.65mm Walther and a 9mm Smith and Wesson. He did his best to remove any doubt from their minds that he would not hesitate to use them.

With this in mind, it seems that Modráček was not necessarily speaking in a manner which sets the Nazis on one side, and himself on another, i.e. how ‘they’ understood things as opposed to how ‘we’ or ‘I’ do; he was giving voice to one possible manner of human expression, such as he would put into practice himself if it so suited him. To return to Alžběta Hajná’s account, we find Modráček actually using the same sort of euphemistic imagery to cover his evil as that found in the showers of Auschwitz, with their gay decorative tiles of water sports:

I managed, the architect said, to squeeze into an area that is none too large everything that you need for a comfortable life, and I did everything that was in my power, I really like it when you say things like that to us, Dan Kočí said at that, we worked like slaves at this avant-garde architectural opus of yours, just like the slaves that built the pyramids while you just strolled about with a pistol at your hip and we considered ourselves fortunate that you didn’t urge us on with whips and cat-o-nine-tails.

It is in this very aspect of his story, where it doesn’t even occur to Modráček that his ‘underground Utopia’ doesn’t just mirror the Communist ‘Utopia’ above, but actually Buchenwald, Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, that Kratochvil’s story explodes beyond 1950s Czechoslovakia to reach us — overcoming me, as I said at the outset, in a small church in upstate New York.

hi, i’m kamil. pleased to meet you

Modráček’s story is bigger than him. Kratochvil will not permit us the comfort of using the architect as a scapegoat. To return to the sociological/psychological eloquence of The Vow, it is patent that this is a novel which is a deft, and depressing, psychological study of human nature. Although I beg not to be misunderstood here according to the jargon of contemporary liberal sociobabble, The Vow is a study of relationships of power.

Whenever I would enter the stationhouse on Běhounská I would submit myself to a process, which had something of the invariability of strict ritual to it. The StB goon who served as porter had to call upstairs and wait for confirmation that, indeed, I had been summoned. Upstairs, of course, they always took their time. So I would stand there, and in the interim, which sometimes stretched into quite a long period of time, while the StB functionary seemed to take no notice of me. But God forbid that I should make the slightest movement in any direction. No, I had to stand there rooted to the spot. At most, I might shift my weight from one foot to the other, or flex my fingers and toes. Then, at last, the phone would ring and it would be confirmed from above that I had been summoned.

As we have said, the oppressed become oppressors in their turn. Whenever the torturer-in-chief cedes his place, one of the previously tormented is more than willing to jump behind the controls and administer the same voltage to those further down the food-chain. Could this be learned behaviour? Or is it, as I suggested at the outset, something endemic to human nature?

Most shiver-inducing of all is the way that, for each ‘rebel’ like Dan Kočí, who won’t allow Modráček to get away with that kind of thing, as Alžběta tells us, there are collaborators down below, too: ‘constantly there are found amongst us people such as cooperate with Mr Architect.’ That is to say, there are Capos in Modráček’s Concentration Camp Eden, who not only accept the new reality, but take their oppressor’s side. Whether this is Stockholm Syndrome or a pragmatic desire to reap rewards rather than face punishments is rather beside the point. What we see here is the horror of human nature — the facility to adapt even past self-defence. Another question we might pose (but not wish to consider too closely!) is: Does the experience of being imprisoned in an exploitative, and threatening, environment such as a concentration camp or an ‘underground Utopia’ such as Modráček constructed, and the consequent decision to cooperate with one’s exploiters, signify a change in a given subject’s personality, or a discovery of the same? The humanist would prefer the first, exculpatory, version: had this or that person not been put in a situation in which he or she felt that survival depended on morally disreputable behaviour, he or she would never have indulged in it. The realist, or pessimist, will say: opportunity makes the thief. Perhaps Alžběta’s words concerning the rather repugnant character of the rather fauve chef can be extended to all of Modráček’s tenants: ‘I’m certain that he was no different before Modráček snatched him.’ Despite all the fantastic and ‘magical-realistic’ qualities of Kratochvil’s writings, The Vow is firmly grounded in reality. Quoting Aleš Haman, Michaela Wronová reminds us that:

In his work, Kratochvil does not employ motifs that would shock the reader with strong improbability. Rather, while maintaining the characteristics of fantasy his fiction remains firmly grounded in realia that do not surpass the limits defined by the possibilities of our sensory perception of the world as it is.6

And this goes both for improbable, but still conceivable situations in the physical world, such as Modráček’s construction of the first part of his underground city by himself (who helps him to bring down, and set up, the armoured door?) and in the moral sphere of his characters’ actions.

Perhaps it can be extended to us, too. Kratochvil deftly insinuates the ‘puny god’ who lives inside us all when he has his narrator set a thumbtack on the floor, point up, not once, not twice, but thrice over the space of less than three hundred pages. The last time this occurs is in ‘our’ twenty-first century:

Luděk, it’s eight minutes after midnight. Can I open the window?

Sure.

And Petra got up out of bed naked, and trotted over to the window. But the narrator, who’s already taken a liking for this, has set a thumbtack on her path. Sharp end pointing upwards.