Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

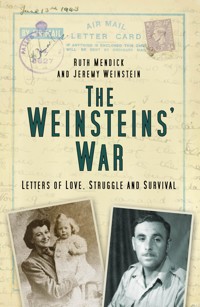

From its onset, the Second World War changed the course of many couples' lives as they were parted, not knowing if they would ever see their partners again. Documenting the hopes and the heartbreak of the young Jewish Weinstein family, this book uses a treasure trove of 700 letters sent between husband and wife to depict the everyday struggles of lovers surviving apart as war wore on in Europe and North Africa. The letters, always vivid, sometimes funny, often passionate, contain intimate details of the pressure on the young couple, dealing with conditions at home and abroad, family and political rivalries, and even tension as talk of the temptation and ease of 'playing away' arises. The Weinsteins' War is an honest portrayal of the strains of sustaining a loving relationship when so far apart and of the hopes the couple had for a new, post-war Britain.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2012

This edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Ruth Mendick and Jeremy Weinstein, 2012, 2022

The right of Ruth Mendick and Jeremy Weinstein to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7524 8120 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

One

Personal Histories

Two

1942: At War in Egypt, Embattled at Home

Three

1943: The Riddle of Sex and Other Questions

Four

1944: A New Stage of the War

Five

1945: Victory in Europe and in the General Election

Six

1946: Disappointment, Shock and Anticipation of the Future

Seven

Afterthoughts

Bibliography

Introduction

This is the story of the Second World War as experienced by one young family, David and Sylvia Weinstein and their little daughter, Ruth, and discovered through the 700 or so letters that they sent to each other. The letters begin in 1942, when David first went abroad on active service (having joined up in 1940), through to his discharge home in 1946.

David’s war was a busy one. As a soldier in the Eighth Army, a gunner, he was at El Alamein in North Africa and then at the landings in Sicily, which then led to his trek through Europe, including being part of the barrage supporting Operation Market Garden. He ended the war as a member of the Army of Occupation in Germany. As the regimental tailor, he turned up sleeves, sewed on insignia and oversaw the work of a group of Germans who were part of his team. Here he had a coat made for Ruth: it was too big for her but she would ‘grow into it’, he writes, a metaphor, perhaps, for his life in the services. He survived, even thrived, by developing physically, socially and psychologically, growing into his uniform so that it fit every contour of his being, with a tucking-in here and an addition there. David was at times enormously proud of what he had become, and sometimes he felt distinctly uncomfortable. His letters provide fascinating insights into the battles he fights and also the extraordinary ordinariness of the routine life of a soldier. He continually observed and commented upon the cities, towns and villages he passed through and the people he met: refugees, families he was billeted upon, women who turned to prostitution and black marketeers, as well as his fellow soldiers. There were some light moments alongside the grim or exciting: he helped milk cows and deliver babies, he had Sylvia send him subscriptions to socialist papers like The Daily Worker and Reynold’s News and asked also for mysteries and westerns with names like The Mystery of the Semi-Nude and She Strangled Her Lover (letter dated 12.07.44).

He was helped throughout by his knowledge of Yiddish, learnt back home with his family and in the Jewish East End of London, which lent itself so well to the mix of German and Dutch that became the language of wartime Europe. This background also gave him a sharp interest in the Jewish/Palestinian soldiers that he met at various points and there is poignancy in his friendship with the German Jews he encountered on their return from the camps. These experiences, along with the marking of the various religious festivals while out in the field, even under fire, left David intensely aware of what it meant to be Jewish at this momentous time in the world’s history. David kept a political eye open on all that he saw and read, and showed his intense excitement for the post-war Britain, and Europe, that was emerging. Having helped achieve the victory in war, the letters end with him anticipating the part that he and Sylvia can play in helping a Labour Britain win the peace.

Sylvia’s war, on the Home Front, was no less eventful or dangerous. In retrospect we know that the worst of the Blitz was over, but her letters reveal the continuing fear of danger, death and destruction from the skies and the constant struggle to adjust to and cope with the deprivations and fears of what has been termed the first example of ‘total war’. An especially significant factor for Sylvia was that she had recently left, or escaped, her large, close but complicated family after becoming a wife and a mother and sharing a business with David. Then, in April 1941, they were bombed out and she found herself back with her family. This was initially with her sister Fay, in Ilford, in a small premises above a grocer’s shop that had to be shared with Fay’s own young family, two boys aged 5 and 7 plus a sister-in-law, Betty, aged 19. David and Sam, Fay’s husband, were also there when on leave from the army. Sylvia and Ruth then moved, in 1944, to Frome, Somerset, where other family members had gone to escape the London bombings. Sylvia finally returned to set up home in Walthamstow, still in East London. While much of the literature about women in the war is about how they found new, transformational roles for themselves, either in such settings as the Land Army or in work (as in the iconic figure of ‘Rosie the Riveter’ (also see the accounts collected by Nicholson, 2011)), Sylvia’s was a more internal, domestic struggle to survive; she describes herself as ‘the odd one’ in her family (08.12.42), managing what we would now call a single-parent family. She organised rations, dealt with the continued bombings, negotiated with the authorities and weathered the tensions and rivalries within her wider family, while parenting her own daughter and sustaining Ruth’s muddled relationship with a father that was missing at such a crucial time in her young life as she grew from being a toddler to having her first day at school.

Both David and Sylvia had an urgent need to share the details of their own world and to know as much as possible of their spouse’s experiences – to enter their parallel life as fully as possible. Thus David seized on the smallest details of Sylvia’s domestic circumstances and of Ruth’s development while Sylvia listened to the radio, followed the papers, watched the newsreels and equally avidly awaited and devoured David’s letters. They used the letters as best they could to continue the intimate relationship of a still-new marriage that had been so rudely interrupted by the war and which no one knew when or if it would be resumed. This is a conversation about war, religion and politics as well as the more intimate aspects of family, love and sexual longing. The importance of the correspondence is most eloquently expressed by David and Sylvia themselves. Thus Sylvia writes how ‘it does seem to bring us closer to one another. I can feel your presence … when I read those dear letters that you write these days’ (03.05.43), while David refers to how ‘I can have spiritual contact with you by writing’ (19.05.43). In the extracts that follow David’s spelling has not been corrected – he jokingly defends his spelling as ‘modern’ against Sylvia’s ‘old fashioned’ approach (21.08.45).

While the letters provide a very striking story of their lives and struggles they do not, of course, provide a complete story. At their most basic they can be just a tick-box affair. A pre-prepared letter (27.10.44) from the senior Jewish chaplain leaves spaces for the Revd Levy to write in ‘Mrs Weinstein’, followed by the typed ‘I have to-day seen’, with ‘your husband’ again there by hand, followed by the typed ‘I am sure you will be pleased to know that I found him well and in good spirits’. The reverend does apologise for the ‘very impersonal form of note’. David sends (07.07.45) a field service postcard, which has a number of phrases that can be struck out as appropriate. The choice includes such bald statements as ‘been admitted to hospital because of sickness or wounds’, ‘a letter, telegram and/or parcel has been received’ or complaining that ‘no letter has been received’ either ‘lately’ or ‘not at all’. David ticks the message ‘I am quite well, letter follows at first opportunity’. There were telegrams for urgent news, airgraphs which were very short and so necessarily to the point, letter-cards and, most valued in terms of length, airmail letters, which could take four to five months to reach their destination. Sylvia and David were clear about their preferences, David writing (20.12.42) that:

[Y]our air-graphs are very sweet tasters, but your letters are like a jolly good feed, and though they take so long and contain old news, never-the-less they are more than welcome.

The letters were also written in the shadow of the censor. The unit commander was expected to scrutinise all correspondence to prevent the leaking of sensitive military information and to assess the mood of the men. Consequently soldiers tended to entrust their more personal thoughts to ‘the green envelopes’ which were less often opened at source, and, even then, would be opened by the base commander who was more distant from the men and so was less likely to know them personally. There was also self-censorship, giving the letters a cautionary feel as they struggled to find a way to talk to each other about their fears, frustrations and intimacies. David apologises (23.09.44), wishing that he ‘had the nack of expressing myself’, while Sylvia (18.08.42) comments:

Anyway, Davie, it is rather awkward being intimate with a piece of paper, if you get my meaning. – But I do usually write what I want to, and who cares who reads it.

The self-censorship is also seen in how much time David needed to tell the full story; thus he describes a battle he was in, what we now know as Operation Market Garden, but it was a while before the censor allowed him to give a fuller set of details and it then took further time before David felt able to disclose the personal impact that the battle had on him. David was careful sometimes in what he wrote and hurt his wife when she found the phrase ‘don’t tell Sylvia’ in a letter to another family member (08.12.42). David and Sylvia also experienced frustrations when letters were delayed because of bad weather or rapid troop movements, or when others got damaged in transit or were lost completely.

For all their limitations, however, the letters represent a fascinating account and both David and Sylvia seem to have been aware of the significance of what they were writing. David comments (23.09.44) that his could be ‘the basis of one of the greatest books yet to be written’ and (02.02.43) that Sylvia’s letters read:

almost like a book. When I get back home P.G. [abbreviation for ‘Please God’] I shall have them printed as a book and title it ‘The Memoirs of a soldiers wife’. It will amuse Ruth in later years they are certainly an enfolding tale of a child’s early development, as well as the fears, hopes and future of an anxious loving wife.

What follows, then, serves as the book that neither wrote but could and perhaps should have done. We, the editors, the children of David and Sylvia, have drawn on the letters, taking up what seem to be the most important themes for a wider readership, using always the words of David and Sylvia themselves but with footnotes at the end of each chapter if readers are interested in a wider context. There are also the memories of those all too few family members who shared this momentous point in history.

One

Personal Histories

Personal Histories sketches out David and Sylvia’s family backgrounds and their lives up to the outbreak of war. It also suggests the influences of the Jewish East End on their subsequent experiences of war.

David was the son of Hyman Vashan, born in Balta, a village near Odessa, in 1884, and of Sima Elezatsky, six years younger than her husband and from a village 100 miles north-east of Moscow. They came to London at the turn of the century, part of a wave of Jewish immigrants fleeing pogroms and poverty, and it was at the port coming into England that an official changed their name to ‘Weinstein’. Presumably, rather than struggling with the accent and lack of English, it was easier to assume that another ‘Yid’ from Eastern Europe must be called some variation on the name ‘Stein’. Once settled, Hyman started a second-hand clothes shop. David was born in the East End of London in 1912, first living in Cable Street, later Whitechapel Street. He went to a school that still stands, and which he called ‘Checker Alley’ (actually Checker Street, and the school has now been converted into a gated community of private housing) where, he would further joke, the board celebrating pupils’ achievements had fallen into dilapidation through under use. It can be assumed that David had a traditional Jewish upbringing and certainly there are a number of Biblical and religious references in his letters. When Vera, Sima’s sister, died, among her possessions were some leaflets produced by the Bund, the mass Jewish socialist party in Russia and Poland, which indicates political talk in the home.

There were five children: David had one younger brother, Alf, who is often mentioned in the letters, and three sisters, Doris, Betty and Eva. Alf was single and although two of the sisters were married, they were childless; David, of course, had a child, Ruth, born in 1940 following his marriage to Sylvia in 1937. David’s concern for his younger brother, who was also serving in the war, often surfaces in the letters.

Sylvia was born in 1914. Her mother, Alta Melenek, originally lived 40 miles north of Warsaw, and her father, Abraham Ruda (later known as Rudoff), was born in 1876 in Zakroczym, 50 miles north-west of Warsaw. There is a very formal photograph portrait of him as a soldier in the tsar’s army. As with the Vashans/Weinsteins, the family came to Britain at the turn of the twentieth century, bringing with them the two eldest children, Millie and Belle. According to the unpublished biography of his son, Lou Ryder (Ryder, 1994), Abraham had intended to join his older brother in Argentina, but financial pressures meant that he settled for, and settled in, Cable Street. Alta had eleven children in all; two died in infancy and of the surviving ones Sylvia, born in 1916, was the second youngest. Abraham was a deeply religious man, later founding a synagogue in the unlikely setting of Frome, Somerset, in the front room of the house where they stayed during the war, and then another in Ilford. His faith led him to break off completely contact with a brother, Hymie, who was a communist and atheist. Abraham also worked as a tailor dealing in second-hand clothes (‘the Shmutter trade’) and some property. Sylvia refers in her letters to helping to prepare the rent books.

When Sylvia was 4 the family moved to Amhurst Road in Stoke Newington, where they stayed for ten years, and then to Highbury. However this is to jump ahead of a major disaster in the life of Sylvia and the whole family. In 1923, when Sylvia was just 7, her mother, Alta, died following a routine gallstones operation. Something of the personal impact of this is reflected in Sylvia telling the toddler Ruth, who sees the yahtzeit (memorial) candle burning, that ‘when I was a little girl I was naughty and my mummy went away and left me’ (letter to David, 31.05.43). Life then became ‘chaotic’ (Ryder, 1994, p.18). The two oldest sisters were already married so it was left to the 17-year-old Esther to run the home until Abraham married a factory worker, Sarah (ever after called ‘Aunt’), and Lou comments that although Sylvia ‘soon adjusted … she became very hostile later’ (Ryder, 1994, p.19).

Sylvia was very bright at school, especially at maths, gaining a scholarship at 11, but her hopes of becoming a teacher were thwarted by the family’s poverty and a lack of commitment to women having a career. She left school at 16 to start work at a grocer’s, a disappointment that stayed with her throughout her life.

In the letters there are frequent references to her eldest sister, Millie, who took on the matriarchal role in the family, and her son, Lionel, away in Canada training with the RAF, also provokes much comment. Sylvia’s younger brothers, Lou and Ralph, are also mentioned frequently.

The East End where David and Sylvia lived is familiar from a whole host of memoirs, novels and historical studies. Lou saw it as a place of ‘narrow cobbled streets, permanently muddied and generously sprinkled with horse manure. Streets where the sun was ashamed to show its face’ (Ryder, 1994, p.8). Joe Jacobs describes (1978) the crowded housing and the struggle to find work, which seems to have been typical, and also an atmosphere where ‘the adults sat on chairs on the pavements outside the front doors talking, laughing, arguing very excitedly during the evening and late into the night’ (p.21). David was a tailor so he was likely to recognise Jacobs’ description of the headquarters of the Tailors’ and Garment Workers’ Trade Union for Gents’ Tailoring:

There were … offices either side of the passage which led to a wider wooden staircase … there were small openings covered by panels which slid up and you talk to a face on the other side. Climbing the stairs you would hear voices often very loud above the general gabble of conversation mostly in Yiddish. In addition loud bangs as the dominoes hit the table tops. On entering a very large room, occupying the whole of that floor, the cigarette smoke would almost cause you to choke. Here, during the daytime, were the men who were unemployed, to be joined in the late evenings by those who had been working. Teas and snacks of all kinds were available, at a small bar occupying one corner. The floor above had several rooms in which there was always some sort of meeting going on. (p.20)

This was where David’s education started, in the setting of the labour movement, through the books of the Left Book Club, and at meetings first of the Independent Labour Party (a form from the London and Southern Counties Divisional Council of the ILP dated 25 July 1933 certifies that Mr David Weinstein of 102 Whitechapel Street, Finsbury E.C. is the agent for the ILP) and then the Labour Party, whereas other friends, including Phil who features in the wartime letters, joined the Communist Party. David spoke at street-corner meetings with the likes of Tom Mann, so he was at the centre of political turmoil, and Lou Ryder describes David being struck by police batons during a demonstration in support of the unemployed (Ryder, 1994, p.64). David leaving school coincided with the 1926 General Strike, and the clashes with Mosley’s fascists, most famously the Battle of Cable Street in 1936 (although he never talked about this with us, his children, or perhaps we never asked). The concerns about fascism would inevitably play heavily on his mind, and while the Left Book Club texts covered a whole range of political issues, both contemporary and historical, what now stands out is a slim volume entitled The Jewish Question (1937) which starts by asserting that there is ‘hardly a country under the sun where the Jew is safe from insult’ (p.7) and also a fuller book, published in 1936, that documents in close and chilling detail the growing persecution of the Jews under the Nazis. Its title is The Yellow Spot: The Extermination of the Jews in Germany.

It is important to give this background because the David we see in the letters has all the energy and passion of his East End youth, in all its complexity of religion, politics, culture and family life. There is an urge to meet people and get to know them.

Sylvia was also a part of this political atmosphere, inevitably so since she was courting and then married to David while her brother Lou was also active in socialist politics. Lou later chose to become a conscientious objector, so we can assume that, as war approached, there were arguments about pacifism. The letters illustrate her political take on the war and there is anger when she witnesses Jim Crow racism directed against black GIs. When the country prepares for the 1945 General Election she reports back to David on the Labour Party meetings she attends.

Sylvia and David came together as a mix of the two families, the Weinsteins and the Rudoffs, with David’s sister, Doris, marrying Lou, Sylvia’s brother (subsequently made even more confusing when, post-war, David’s brother Alf married Sylvia’s niece, Evelyn, the daughter of Millie). As Sylvia describes it (18.05.43) she and David had been ‘at the “walking out” stage for years, and even then were engaged for fifteen months before we were married’. They eventually married in 1937, combining what David described (31.07.45) as ‘the Weinstein temperament, taking things as they come’ with the ‘brains’ that come from the ‘Rudoff family’. Ruth was born in 1940 and they set up in business, which also served as a home since they lived in a flat above the shop, but they were bombed out in 1941. David was then sent abroad with the army in 1942. From this point on the letters continue the tale.

Two

1942

At War in Egypt, Embattled at Home

In these early letters we see David and Sylvia getting into a rhythm of writing, finding a style that will see them through the war. They describe the emerging rituals that will keep them in tune with each other. Sylvia shares details of Ruth growing up, the nature of her shared home with her sister and her family and the restrictions of life in London, where she was always at risk, whether from predatory men, dead mice in the bath or the continuing menace of German bombs. David gives vivid details of his 12,000-mile boat journey from the UK to Tufic on the Suez Canal and then his often quite contradictory impressions of Egypt and especially Cairo. He sees action at the Battle of El Alamein and ends 1942 exhausted and recuperating in hospital in Alexandria.

Starting Off: Finding the Rhythm and the Rituals of Absence

At this point Sylvia and Ruth, aged 2, had been bombed out of their own home and business, and were living in Ilford in a small premises above a grocer’s shop, which had to be shared with her sister, Fay, Fay’s own young family, Jeffrey and Tony, aged 5 and 7, plus a young sister-in-law, Betty, aged 19. David and Fay’s husband, Sam, would also be there when on leave from the army. Jeffrey recalls the premises being on two floors – three including the shop. Apart from the bedrooms there was a kitchen with a bath in it, a front room which was ‘for best’, and so never used, and a dining room in which they played, lived and ate. The cupboard under the stairs served as a shelter during air raids.

David was posted in Bromley during this initial stage of his army life and home leave, and the telephone meant that the letters lost their importance as a means of keeping in touch. There is one, dated 23 February 1942, which is six pages long, pencil written and following a leave of:

two days and one night … Baby was grand, and I have a feeling that this time she really did miss me … It’s a grand feeling to have a woman excite me like you do … and I feel honoured to think that I satisfy all your demands.

David writes about the pain of being apart and tells Sylvia ‘to keep your chin up … PG when all this is over, this world will be for us and us alone’. What follows are some travel details and then he returns to his love for the family: ‘I’m a happy man, it’s great to have such a wife and baby.’

Similar themes are in his letter dated 25 May 1942, but of a different order: he is on the point of being sent abroad, which serves to concentrate the mind:

My dearest Sylvia,

I felt that I must write even though I have seen you so often.

In these last few weeks there have been a lot of occasions when I have felt like having a good old weep, but have kept them back for your sake, I wanted to be brave as you are.

I shall always remember you with a smile on your lips and tears in your eyes, and looking so brave, it was then, as the bus was going that I knew I loved you more than ever.

I felt a proud man, to have a women like you, and when I thought of baby I was indeed a happy husband and a proud father.

Well beloved all I can say now is that God Bless you and baby, and bring me back safe and sound to you both.

Start from to-night dear, and concentrate your thoughts on me, and I shall do likewise, at exactly 10 o’clock every night, and I am sure that though far away, we will, at that moment be very near.

So cheerio my dear, it won’t be long before I am with you again for all time so chin up darling the clouds will soon roll by.

With all my love

Sylvia writes on 30 May 1942, apparently not yet having received David’s letter:

My dearest David,

I am writing to you again now, though I have my doubts as to whether this letter will reach you. I am sending it to your old address, and shall just hope for the best. I do wish I could get a letter from you – I do miss them, you know darling.

We are all quite O.K. here, but naturally miss you like hell. Ruth makes such a fuss of your photo when she kisses you ‘goodnight’. She is also beginning to help say her prayers – she says the last couple of words to each line. It is remarkable how she knows some of the words.

‘make Root a ……. goo gel’

‘keep her strong …….. an’ helfy’

‘and please bring daddie …….. backy soon’

‘and keep him safe ……… an’ wayel’

I took Jeff to pictures last night – Friday – to see ‘They died with their boots on’. We enjoyed it very much, though we had to queue for a few minutes. I caught sight of the sign opposite the Regal advertising ‘Pirelli’ tyres, and it took me back some way – remember?

We all went shopping this afternoon – that is, Fay, myself and the three ‘kids’ (as Ruth calls them). We finished up in the Lyon’s for ‘ee-cream and Ruth thoroughly enjoyed it. She is a terror though, she does everything the boys do. She won’t let me hold her hand, and runs along the road expecting all and sundry to make way for her. She likes to trail her hand along the dirty shop window ledges and you can imagine the state she gets into. She certainly does need restraining, but we must wait until you come home for that. The trouble is she can be so sweet and loving too. When I hold her out at night (and I never forget to give her a kiss for you then) she cuddles up to me and gives me a kiss and murmurs ‘nice mummy’ – all this while she is soundly sleeping. So how can I really get annoyed with the monkey?

Ralph is off to see Dad on Monday. – We are all very worried about Dad. – Millie has given us a very serious report of what the specialist has said. It seems it is some disease of the heart, and he must not receive a shock of any sort. Ralph’s affair must have upset him, and to ease the effect of when Ralph comes back, Sam (Belle’s) is going down on Tuesday for a few days. It will make a rest for Sam too. We don’t know what to suggest about Dad – I don’t think he knows himself how seriously ill he is.

Well, David my dear, I seem to have no news that I can tell you. We are, naturally, all looking forward to your speedy return, so hurry up and finish the job.

Goodnight darling and God bless you always.—

Love from Betty and Fay,

Yours as ever,

Sylvia.

X from RuthX from me.

Managing being apart was not easy. In one letter (14.07.10) Sylvia confesses that although it has been only seven weeks since she last saw David ‘it feels like seven years, or seventy’. She goes on to confess:

I find it so difficult to remember what you look like – I keep studying your photographs, and recalling that when you were here I thought they were an excellent likeness, so they must be.

On Board the Laconia Off to Reinforce the Troops in North Africa

David left in May for the 12,000-mile journey to North Africa. After the shock of the fall of Tobruk, troops were needed to take on Rommel, and David, as a gunner in the 44th Division, along with the 51st Division, was part of those reinforcements.

His ship was the Laconia, a requisitioned cruise liner.1 David did write (07.07.42) but warned that, given the circumstances, this might be the last he could send ‘for at least two months’, although he hoped ‘if it is at all possible’ to send a cablegram during the voyage. In the event he did rather better than this.

In this first letter (07.07.42) he describes leaving Bromley and then the sea voyage. This letter is difficult to read in places, since the censor has literally cut out words and, as the letter is double sided, the effect is quite widespread:

We paraded in full marching order, that is carrying everything, and we were really loaded. Then came the usual inspections first the Sgt Majors, then the Troop Commanders, then the C.O. then at 9 o’clock we actually moved, getting to the station at about 9.30, we then entrained and started on our journey at 10.30.

Then they boarded:

We were all leaning over the side watching the land receeding from view.

I wonder what all our thoughts were? Mine were very full of mixed emotions, and my thoughts were of you and all that was dear to me.

Even now as I write tears are very near to my eyes, all I can think of now is to get this blasted war over … the sea choppy and very grey, and I have been violently sea sick for one day … this sea sickness is a really rotten feeling, you wish that you had not been born …

Well now for life on board, it is all very boreing, we are over crowded, and have to make our own amusements. The promanard deck is for officers only, and the lower deck is for Sgts., and W.O.s, so we are left the lower deck. The food is good, and an issue three times weekly of fresh fruit is given to everyone … There is a good library, so there is plenty of reading matter, and that suits me very well. Cigs are very cheap paying 3d for ten for Woodbine and 20 for 8d Gold Flake. So living is very cheap. There are about 12 nurses on board here, so competition for their favours amongst the officers is very keen.

The most important thing … is how we sleep … hammocks … so close to-gether, that when the chaps either side of me breath out my hammock con [cut out] when they breath in it expands … for all that I sleep very well.

Facilities for washing and for other things is very good, and everything is spotlessly clean. Water is rationed, but sea water showers are on all day, so there is no need for anyone to be dirty.

P.S. We have no wireless on board, but there is a news sheet printed out and that is the only way in which we are in contact with world events, and it is only a very brief summary of the B.B.C. news. Why I have written this is because I have just read that on 3rd of June London was visited by enemy aircraft but only a few bombs were dropped. I hope dear that everything is O.K. but please look after yourself.

It will be grand seeing land again, even if it only be trees and mud huts … The journey has been peaceful and uneventful for which I suppose we have to thank God.

… Sea, sea and more sea, I did not know there was so much water. We have now travelled over [censored] and are getting into warmer weather, [this last phrase has a pencil line through it and above it is written, in pencil] and the weather is quite warm and the sea is like a pond … let me tell you my dear, that the sea is grey, and not blue, it is only blue when the sun shines on it, and there is nothing good about it.

Been looking at the snaps I have of you and ‘baby’, and have been thinking a great deal, it hurts to look at them, and yet I would not be with-out them, it is the world [cut out] baby and I, P.G. will be with you again just us three (for a little while at least.)

In a subsequent letter (16.06.42) he describes the ship as ‘over crowded and sweaty … not a very enjoyable trip at all’. He was, nevertheless, ‘feeling fit and excited’; he was ‘going to make the best’ of what promised to be ‘a completely new experience for me’, although it was tempered by the fact that ‘I had to leave you and baby behind’. To make up for this he promised ‘that we are going to have a sea trip to-gether (Please God) after this darn war is over’.

He describes various ways of passing the time: letter writing, reading, playing ‘Housey-Housey’ and card games, ‘interesting lectures’ and ‘a minature brains trust’. There was ‘a sing-song on deck in the cool of the night with a nice breeze … blowing, a welcome relief from the heat of the day’. The songs were:

all sentimental ditties, ‘Old fashioned lady’ ‘Danny Boy’ ‘We’ll meet again’ ‘In apple blossom time’ ‘When they sound the last all clear’ and the favourite song ‘The white cliffs of Dover’. What thoughts of home they conjour up, and what memories of happier days … it’s nice to … lose one self in song.

He follows the news of the war as best he can and it sounds ‘discouraging’ and he wonders ‘what is really happening, news on the ship is very sketchy’. The letter ends abruptly, however, because someone ‘wants to sleep on the table, you see my dear, we sleep and eat in the same place’. He only has time to add ‘Sweet dreams and God Bless, give baby a nice big “cuddy” for me’.

Another, very contrasting, story of life on board was given by Ralph en route for India. Sylvia summarises the letter for David (04.08.42). Ralph’s cabin was shared with five other sergeants and had a cool-air ventilator set into the wall so that his:

greatest joy was to strip and stand on a chair in front of this, and move the ventilator so that the cool breeze played all over the body. He can buy, by queuing up at the right time … Libby’s peaches and tinned milk – quite cheap, too. I wonder if you fellows get a fair share of all that’s going? or is it snapped up by the officers and N.C.O’s?

David’s voyage broke off in South Africa and Sylvia subsequently received a letter from a Mr Light (03.07.42), on paper naming him as a director of Salt River Sweets Works Ltd in Cape Town, giving news that ‘we had the pleasure of entertaining your beloved husband. He spent a very pleasant evening at our home.’

Arriving in Egypt

David disembarked on 27 July at Tufic on the Suez Canal and his impressions (01.08.42) were stark; there was: