0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Arcadia Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

"... I have not had the privilege of attending schools, so it is very hard for me to tell my story with the pen; but perhaps I may be able to give my readers, young and old, some pleasure and help them to get a clearer, truer picture of the real wild West as it was when the pioneers first blazed their way into the land".

“Uncle Nick” Wilson

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

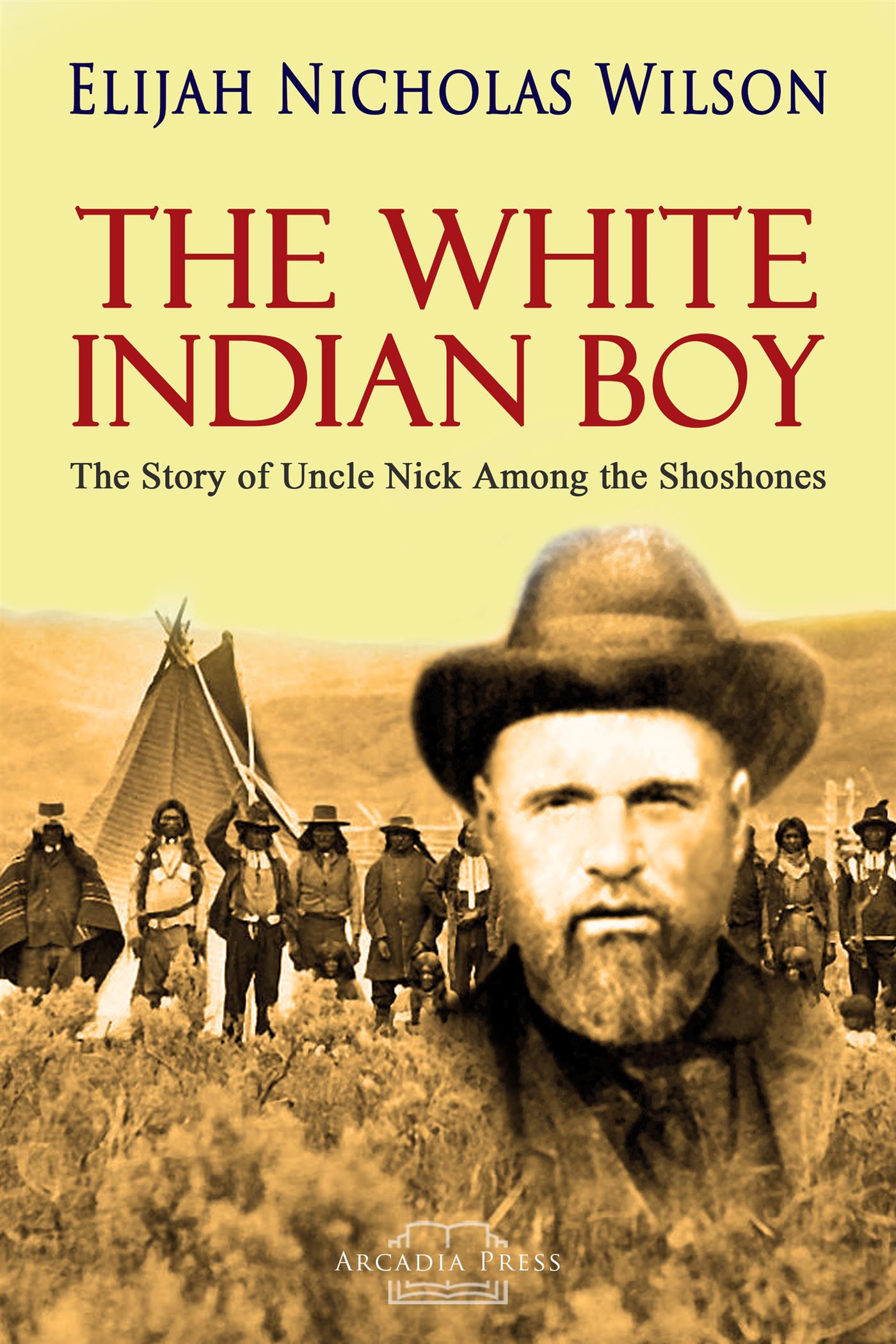

Elijah Nicholas Wilson

THE WHITE INDIAN BOY

The Story of Uncle Nick Among the Shoshones

Copyright © E. N. Wilson

The White Indian Boy

(1910)

Arcadia Press 2020

www.arcadiapress.eu

Storewww.arcadiaebookstore.eu

TABLE OF CONTENTS

THE WHITE INDIAN BOY

AN INTRODUCTION TO UNCLE NICK

If you ever go to the Yellowstone Park by way of Jackson’s Hole, you will most likely pass through Wilson, Wyoming. It is a picturesque little village situated at the foot of the Teton Mountains. A clear stream, rightly named Fish Creek, winds its way through the place. On the very edge of this sparkling mountain stream stands a log cabin. The cabin is so near the creek, indeed, that one might stand in the dooryard and catch fish. And this is what “Uncle Nick” Wilson, who lived in the cabin, has done many a time. That is a “true fish story,” I am sure, because I caught two lively trout myself last summer in this same creek only a few rods from the cabin.

Who was Uncle Nick Wilson? you ask. He was an old pioneer after whom this frontier town was named. He was the man, too, who wrote this story book. You would have liked Uncle Nick, I know. He was a rather short, round-faced man with a merry twinkle in his eyes. He took things easily; he spoke in a quiet voice; he was never too busy to help his neighbors; he liked a good joke; he was always ready to chat awhile; and he never failed to have a good story to tell, especially to the children.

Uncle Nick had one peculiarity. He did not like to take off his hat, even when he went into a house. I often wondered why, but I did not like to ask him. One day, however, some one told me the reason. It was because he had once been shot in the head with an arrow by an Indian. The scar was still there.

From outward appearances one would hardly have guessed that Uncle Nick’s life had been so full of exciting experiences. But when he was sitting about the campfire at night or at the fireside with a group of boys and girls, he would often get to telling his tales of the Indians and the Pony Express; and his hearers would never let him stop. My own two boys never got sleepy when Uncle Nick was in the house; they would keep calling for his stories again and again.

This was one reason why he wrote this story book. He wanted boys and girls to have the pleasure of reading his stories as often as they pleased. How he was induced to write it is an interesting story in itself.

Some years ago two professors of a certain Western university were making a trip with their families to the Yellowstone Park by way of Jackson’s Hole trail. As they were passing through Wilson, one of the women in the party met with a serious accident. Her little boy had got among the horses, and the mother, in trying to save the child from harm, was knocked down and trampled.

Help must be had at once; but how to get it was a problem. The nearest doctor was over sixty miles away. While the unfortunate travelers were worrying about what to do, Uncle Nick’s wife came to the rescue. She quietly assumed command of affairs, directed the making of a litter, and insisted that the wounded lady be carried to her cabin home a short distance away. Then she turned nurse, dressed the wounds, and attended the sufferer until she was well enough to resume the journey.

The party meantime camped near by, and whiled away about three weeks in fishing and hunting and enjoying Uncle Nick’s stories of the Wild West. Every night they would sit about the cabin fire listening to the old frontiersman tell his “Injun stories” and his other thrilling adventures of the early days. They felt that these stories should be written for everybody to enjoy. They were so enthusiastic in their desire to have it done that Uncle Nick finally consented to try to write them.

It was a hard task for him. He had never attended school a day in his life; but his wife had taught him his alphabet, and he had learned to read and spell in some kind of way. He got an old typewriter and set to work. Day by day for several months he clicked away, until most of his stories were told. And here they are — true stories, of real Indians, as our pioneer parents knew them about seventy years ago.

The book gives the nearest and clearest of views of Indian home-life; it is filled, too, with stirring incidents of Indian warfare, of the Pony Express and Overland Stage, and other exciting frontier experiences.

Uncle Nick may have had no schooling except as he got it in the wilds, but he certainly learned how to tell a story well. The charm of his style lies in its Robinson Crusoe simplicity and its touches of Western humor.

Best of all, the stories Uncle Nick tells are true. For many months he was a visitor at our home. To listen to this kindly, honest old man was to believe his words. But the truth of what he tells is proved by the words of many other persons who knew him well, and others who have had similar experiences. For several years I have been proving these stories by talking with other pioneers, mountaineers, pony riders, students of Indian life, and even Indians themselves. Their words have unfailingly borne out the statements of the writer of this book. No pretense is made that this volume is without error. It certainly is accurate, however, in practically every detail, and true to the customs and the spirit of the Indian and pioneer life it portrays.

Professor Franklin T. Baker of Columbia University, who read the book in manuscript, has pronounced the book “a rare find, and a distinctive contribution to the literature that reflects our Western life.”

The rugged, kindly man who lived through the scenes herein pictured has passed away. He died at Wilson, the town he founded, in December, 1915, during the seventy-third year of his age. But he has left for us this tablet to his memory, a simple story of a simple man who lived bravely and cheerily in the storm and stress of earlier days, taking his part even from boyhood with the full measure of a man.

Howard R. Driggs

AUTHOR’S FOREWORD

You have no doubt read or heard stories of the great wild West. Perhaps you have even listened to some gray-haired man or woman tell tales of the Indians and the trappers, who roamed over the hills and plains. They may have told you, too, of the daring Pony Express riders who used to go dashing along the wild trails over the prairies and mountains and desert, carrying the mails, and of the Overland men who drove their stages loaded with letters and passengers along the same dangerous roads.

I know something about those stirring early times. More than sixty years of my life have been spent on the Western frontiers, with the pioneers, among the Indians, as a pony rider, a stage driver, a mountaineer, and a ranchman.

I have taken my experiences as they came to me, much as a matter of course, not thinking of them as especially unusual or exciting. Many other men have had similar experiences. They were all bound up in the life we had to live in making the conquest of the West. Others seem, however, to find the stories of my life interesting. My grandchildren and other children, and even grown people, ask me again and again to tell these tales of the earlier days; so I have begun to feel that they may be worth telling and keeping.

That is why I finally decided to write them. It has taken almost more courage to do this than it did actually to live through some of the exciting experiences. I have not had the privilege of attending schools, so it is very hard for me to tell my story with the pen; but perhaps I may be able to give my readers, young and old, some pleasure and help them to get a clearer, truer picture of the real wild West as it was when the pioneers first blazed their way into the land.

“Uncle Nick” Wilson

CHAPTER I

PIONEER DAYS

I was born in Illinois in 1842. I crossed the plains by ox team and came to Utah in 1850. My parents settled in Grantsville, a pioneer village just south of the Great Salt Lake. To protect themselves from the Indians, the settlers grouped their houses close together and built a high wall all around them. Some of the men would stand guard while others worked in the fields. The cattle had to be herded very closely during the day, and corralled at night with a strong guard to keep them from being stolen. But even with all our watchfulness we lost a good many of them. The Indians would steal in and drive our horses and cows away and kill them. Sometimes they killed the people, too.

We built a log schoolhouse in the center of our fort, and near it we erected a very high pole, up which we could run a white flag as a signal if the Indians attempted to run off our cattle, or attack the town or the men in the fields. In this log schoolhouse two old men would stay, taking turns at watching and giving signals when necessary, by raising the flag in the daytime, or by beating a drum at night. For we had in the schoolhouse a big bass drum to rouse the people, and if the Indians made a raid, one of the guards would thump on the old thing.

When the people heard the drum, all the women and children were supposed to rush for the schoolhouse and the men would hurry for the cow corral or take their places along the wall. Often in the dead hours of the night when we were quietly sleeping, we would be startled by the booming old drum. Then you would hear the youngsters coming and squalling from every direction. You bet I was there too. Yes, sir, many is the time I have run for that old schoolhouse clinging to my mother’s apron and bawling “like sixty”; for we all expected to be filled with arrows before we could get there. We could not go outside of the wall without endangering our lives, and when we would lie down at night we never knew what would happen before morning.

The savages that gave us the most trouble were called Gosiutes. They lived in the deserts of Utah and Nevada. Many of them had been banished into the desert from other tribes because of crimes they had committed. The Gosiutes were a mixed breed of good and bad Indians.

They were always poorly clad. In the summer they went almost naked; but in winter they dressed themselves in robes made by twisting and tying rabbit skins together. These robes were generally all they had to wear during the day and all they had to sleep in at night.

They often went hungry, too. The desert had but little food to give them. They found some edible roots, the sego, and tintic, which is a kind of Indian potato, like the artichoke; they gathered sunflower and balzamoriza seeds, and a few berries. The pitch pine tree gave them pine nuts; and for meat they killed rabbits, prairie dogs, mice, lizards, and even snakes. Once in a great while they got a deer or an antelope. The poor savages had a cold and hungry time of it; we could hardly blame them for stealing our cattle and horses to eat.

Yes, they ate horses, too. That was the reason they had no ponies, as did the Bannocks and Shoshones and other tribes. The Gosiutes wandered afoot over the deserts, but this made them great runners. It is said that Yarabe, one of these Indians, once won a wager by beating the Overland Stage in a race of twenty-five miles over the desert. Swift runners like this would slip in and chase away our animals, driving them off and killing them. Our men finally captured old Umbaginny and some other bad Indians that were making the mischief, and made an example of them.

After this they did not trouble us so much, but the settlements were in constant fear and excitement. One incident connected with my father shows this. Our herd boys were returning from Stansbury Island, in the Great Salt Lake, where many cattle were kept. On their way home they met a band of friendly Indians. The boys, in fun, proposed that the Indians chase them into town, firing a few shots to make it seem like a real attack. The Indians agreed, and the chase began. My father saw them coming and grabbed his gun. Before the white jokers could stop him and explain, he had shot down the head Indian’s horse. It took fifty sacks of flour to pay for their fun. The Indians demanded a hundred sacks, but they finally agreed to take half that amount and call things square.

Some of the Indians grew in time to be warm friends with us, and when they did become so, they would help protect us from the wild Indians. At one time Harrison Sevier, a pioneer of Grantsville, was out in the canyon getting wood. “Captain Jack,” a chief of the Gosiutes, was with him. Some wild Indians attacked Sevier and would have killed him, but “Captain Jack” sprang to his defense and beat back the murderous Indians. The chief had most of his clothes torn off and was badly bruised in the fight, but he saved his white friend. Not all the Gosiutes were savages. Old Tabby, another of this tribe, was a friend of my father. How he proved his friendship for us I shall tell later.

A rather amusing thing happened one day to Tabby. He had just got a horse through some kind of trade. Like the other Gosiutes, he was not a very skillful rider. But he would ride his pony. One day this big Indian came galloping along the street towards the blacksmith shop. Riley Judd, the blacksmith, who was always up to pranks, saw Tabby coming, and just as he galloped up, Riley dropped the horse’s hoof he was shoeing, threw up his arms and said,

“Why, how dye do, Tabby!”

Tabby’s pony jumped sidewise, and his rider tumbled off. He picked himself up and turned to the laughing men, saying —

“Ka wino (no good), Riley Judd, too much how dye do.”

Besides our troubles with the Indians, we had to fight the crickets and the grasshoppers. These insects swarmed down from the mountains and devoured every green thing they could find. We had hard work to save our crop. It looked as if starvation was coming. The men got great log rollers and rolled back and forth. Herds of cattle were also driven over the marching crickets to crush them; rushes were piled in their path, and when they crawled into this at night, it would be set on fire. But all seemed in vain. Nothing we could do stopped the scourge.

Then the gulls came by the thousands out of the Great Salt Lake. They dropped among the crickets and gorged and regorged themselves until the foe was checked. No man could pay me money enough to kill one of these birds.

After the cricket war the grasshoppers came to plague us. Great clouds of them would settle down on our fields. Father saved five acres of his grain by giving up the rest to them. We kept the hoppers from settling on this patch by running over and over the field with ropes. We used our bed cords to make a rope long enough.

But it was a starving winter anyway, in spite of all we could do. We were a thousand miles from civilization, surrounded by hostile Indians. We had very little to eat and next to nothing to wear. It was a time of hunger and hardships; but most of the people managed to live through it, and things grew brighter with the spring.

CHAPTER II

MY LITTLE INDIAN BROTHER

A few tame Indians hung around the settlements begging their living. The people had a saying, “It is cheaper to feed them than to fight them,” so they gave them what they could; but the leaders thought it would be better to put them to work to earn their living; so some of the whites hired the Indians. My father made a bargain with old Tosenamp (White-foot) to help him. The Indian had a squaw and one papoose, a boy about my age. They called him Pantsuk.

At that time my father owned a small herd of sheep, and he wanted to move out on his farm, two miles from the settlement, so he could take better care of them. Old Tosenamp thought it would be safe to do so, as most of the Indians there were becoming friendly, and the wild Indians were so far away that it was thought they would not bother us; so we moved out on the farm.

Father put the Indian boy and me to herding the sheep. I had no other boy to play with. Pantsuk and I became greatly attached to each other. I soon learned to talk his language, and Pantsuk and I had great times together for about two years. We trapped chipmunks and birds, shot rabbits with our bows and arrows, and had other kinds of papoose sport.