Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

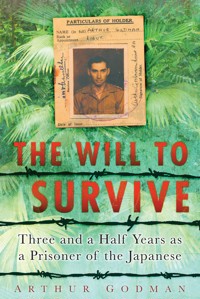

Taken prisoner after the fall of Singapore in 1942, Arthur Godman spent the next three and a half years on the Burma-Siam railway, living in camps along the River Kwai. Like other PoWs, he experienced disease and malnutrition and witnessed the painful deaths of many of his comrades. Yet somehow he retained his sense of humour and perspective, recalling, among the casual cruelties inflicted by the Japanese, small acts of kindness between guards and prisoners which enabled him to retain his faith in humanity. In order to survive he attempted to achieve a relationship with his captors based on their common experience of adversity, learning Thai, teaching bridge and stealing food. The Will to Survive gives the reader a glimpse of the terrifying world of the PoW and includes pictures by another famous captive, Ronald Searle.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 371

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE WILL TO

SURVIVE

THE WILL TO

SURVIVE

Three and a Half Years as a Prisoner of the Japanese

ARTHUR GODMAN

with illustrations by RONALD SEARLE and PHILIP MENINSKY

First published 2002

This paperback edition published 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Arthur Godman, 2002, 2009, 2013

The right of Arthur Godman to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5311 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Introduction

Interlude

Chapter I

We say welcome to sunny Singapore

Chapter II

We’ll never get off the island

Chapter III

The Orient Express to Ban Pong

Chapter IV

The long march

Chapter V

Heigh-ho, heigh-ho, and off to work we go

Chapter VI

The river of no return

Chapter VII

I’m dreaming of a white Christmas

Chapter VIII

Pennies from heaven

Chapter IX

A slow boat to Burma

Chapter X

The golden nail

Chapter XI

On the road to Kanburi

Chapter XII

Mac the knife

Chapter XIII

Teahouse of the Third Moon

Chapter XIV

Strangers in paradise

Chapter XV

The Changi Ritz

Chapter XVI

Confucius – he say

Chapter XVII

Oh Joseph, Joseph, won’t you make your mind up

Chapter XVIII

It’s been a long, long time

Chapter XIX

Epilogue

Appendix

Death Under the Rising Sun

Glossary

Acknowledgements

About the Artists

Introduction

This story actually starts in Changi, a small area on the north eastern tip of Singapore island. How had I come to live in this area and under alien circumstances?

The chain of events which led to my living in Changi began way before the start of the Second World War. I had finished at University College, University of London, at the end of July 1939, and had left with a first class honours degree in chemistry. While at the university I had joined the Officers’ Training Corps (OTC) and had become an instructor in sound ranging, having passed all my OTC examinations. In 1937 I joined the Reserve of Officers, and when war was declared in September 1939, I was instructed to report for duty immediately.

As there appeared to be little demand for sound rangers I was sent on a short course for artillery officers, and then posted to a territorial regiment in January 1940. I did not have long to wait in England; in March the regiment was sent to France. After a period of training the war began in earnest on the 10th of May 1940 and the regiment was despatched with Third Corps to defend Belgium.

We held a defensive position near Oudenarde in Belgium, and I was in charge of the command post for one of the two batteries in the regiment, organizing battery targets. When the Germans attacked, the position was maintained for four days – with some difficulty as our guns were Mark II 18-pounders that the army had discarded in 1916 (being replaced by Mark IV guns). We were withdrawn as field gunners and became anti-tank gunners, with moderate success.

With the army in retreat we fell back towards Dunkirk, where I reached the beaches late in the evening, with about a dozen men. These were from my small anti-tank hunting unit that had lost contact with the rest of the battery. We queued on a small pier for embarking on a destroyer, but missed it by six men. It was full and pulled away – but luck was on our side because the destroyer was heavily shelled out in the harbour.

After a day on the beach at Dunkirk I joined a queue wading out to the launches, climbed aboard a small motor boat that pulled away out into the harbour and then ran aground. As the tide rose we luckily floated off the sand bank, and I eventually climbed aboard a Dutch coastal vessel. This took us to Ramsgate, where we disembarked and were taken by train to a camp to be sorted out into our army formations.

* * *

Feeling restless in England I volunteered for a draft to go to Iraq, but never reached there. At Bombay, I was taken off the troopship and posted to a regiment in Nowshera, a town in the North West Frontier Province of what was then India but is now Pakistan. I was twenty-four years old when I arrived in India – with some experience of actual fighting in a war. The North West Frontier was guarded by three army brigades, with the Nowshera brigade being one of the three. Our duties included the general guarding of the Khyber Pass and the frontier, and acting as depot battery on the gunnery range at Nowshera.

Here was my first introduction to the totally different view of life of the people inhabiting countries in the East. The range was used to calibrate guns, which necessitated an accurate survey of the intended targets. When the guns fired a safety officer was posted to the target area, as well as on the gun - position. This was necessary because the local Pathans had the habit of tying their aged relatives to the targets. If the safety officer did not spot them in time, then the regiment had to pay out – five rupees for a grandfather and three rupees for a grandmother – when they were killed. This was a very different set of social customs from those prevailing in Europe.

* * *

The regiment left India after I had been with them for a few months and went by troopship to Singapore, where it arrived in October 1941 and immediately left for Malaya. Training for the different terrain now began, including altering the camouflage on the vehicles and getting used to jungle conditions.

Arriving in Malaya on 10 October, the regiment was billeted near Ipoh, in northern Malaya. On 1 December our battery was sent to Kelantan, and the other battery of the regiment and the regimental headquarters were sent to Kuantan, both places on the east coast of Malaya. We went by road from Ipoh to Kuala Lumpur, and there entrained for Kelantan, the train journey taking over fifteen hours.

The train arrived at Kuala Krai, at the southern end of the state of Kelantan, and there we alighted. The officers went to the Rest House, one of the - government basic buildings for the accommodation of government officers when on tour. It was on a small hill, about 100 feet high, with a restaurant on the first floor. On the wall in the restaurant was a line about six feet high, marking the flood level for 1926, showing the whole state had been under water at that time. As we had arrived at the season for flooding this was unsettling.

The battery drove north to the small village of Chondong and waited for further orders. There was information that a Japanese convoy was off the east coast of Malaya and likely to land at Patani in Thailand, or at a beach in Kelantan. The state has a coast line about 100 miles long, roughly equivalent to the coast from Suffolk to the bottom of Kent. To defend this area was one enhanced Indian brigade of six battalions, a battery of mountain artillery, and our battery of 4.5 howitzers in reserve, a total of 32 guns.

In spite of the length of coastline, there were only two places where a landing would be effective because of the lack of communicating roads. These places were Sabak beach near Kota Bharu, and Kumassin beach, about 50 miles down the coast from Kota Bharu.

At 10.30pm on 7 December the Japanese started shelling and landing at Sabak beach; 10.30pm in Malaya was the same time as 2.30am on 7 December at Pearl Harbor. Brigadier Keys, in charge of the troops in Kelantan, informed Malay Command of the attack, who, in turn, informed the UK, who informed America – so the attack on Pearl Harbor five hours later should not have come as a surprise.

The battery set off before midnight to a position on the perimeter of the airfield at Kota Bharu, about two miles from the town, and a mile or so from the beach. We set up a gun position in a rubber estate, that being the only suitable position in an area of scrub and pineapple plantations. We could not fire because the Royal Australian Air Force planes were taking off from the airfield to bomb the Japanese convoy – with great success; they sank two transports out of three.

The RAAF evacuated the airfield in mid-afternoon when the Japanese attack made their position untenable; the battery was then able to start firing on enemy positions between the beach and the airfield, in support of the defending Dogra battalion. On the morning of 9 December the Japanese began to take over the airfield, so the battery withdrew; our last task was to destroy the oil tanks on our side of the airfield. Early that morning we passed through the town of Kota Bharu and took up a position about a mile south of the town.

The Japanese captured Kota Bharu town late in the afternoon and the battery withdrew to the first of three main defensive positions on the road leading from Kota Bharu to Kuala Krai. This position was in the grounds of a bungalow overlooking a small river, and was held for a couple of days until the Japanese infiltrated through the jungle to the back of the position. The brigade then withdrew – with the battery providing support from a series of temporary positions, using two guns at a bend in the road – in a series of leap-frogs between the three main positions.

The battery’s next position was at a crossroads with one road leading to Kumassin; one battalion retreated from Kumassin beach down this road to join the rest of the brigade. This position lasted only just over a day. The Japanese infantry could easily filter through the jungle and attack the rear of the positions. They commandeered bicycles from local shops and local people, and used them to cycle swiftly along paths through rubber estates and jungle. The Japanese High Command admitted that a lot of their successful infantry attacks, both on the east and west coasts, depended on the availability of bicycles and good roads and paths for cycling.

There were now insufficient troops available in the brigade to defeat this tactic of outflanking the second main defended position. The brigade therefore withdrew and continued to leap-frog down the road until it reached the last main position, which was defending a padi swamp, with the Japanese having to attack across the padi (cultivated rice plants). The defence lasted longer than was expected because it was difficult for the Japanese to outflank the position.

This last main position defended Kuala Krai, the railhead for Kelantan. South of Kuala Krai was a hundred miles of jungle, with numerous small rivers and swamps, and only the railway made its way through this difficult terrain to Kuala Lipis. It was essential that we held Kuala Krai while trains came from Kuala Lipis to evacuate as much of the brigade as was possible. The infantry were reduced to two battalions, with one troop of our battery supporting the infantry; the other battalions, together with supply units and the other gun troop of our battery, were put on a train. The last train drew in to take the transport, Brigade Headquarters, ammunition, and all but two of the remaining guns. These last two guns kept up a random bombardment for a couple of hours while the train was being loaded, then they were speedily entrained about midnight – a difficult task in the darkness. The train then left, with two battalions marching along the railway track, and the next morning arrived at Kuala Lipis station. It was unloaded and the battery went to a hide in a large rubber estate.

Orders were received to go to Kuala Lumpur, but as Japanese planes were active over Kuala Lipis the move was deferred until nightfall. The night trip was hazardous because the very narrow road wound over the mountains through a pass – the Gap – with hairpin bends. Kuala Lumpur was reached at daybreak and Headquarters contacted. After expressing surprise that no accidents had occurred it ordered the battery to Port Swettenham on the west coast of Malaya, about half way down the peninsula.

Having reached Port Swettenham the battery received orders to guard the coast from Kuala Selangor to Morib, a stretch of about 80 miles, with Port Swettenham roughly in the middle of the coastline. There were three places where a landing could take place with a communicating road system; these were Kuala Selangor, Port Swettenham, and Morib. Two guns were sent to Kuala Selangor, two to Morib, and the remaining four guns kept at Port Swettenham.

A battalion of the Malay Volunteer Force and a battery of guns from the Malay Volunteer Force were sent as reinforcements, so our battery was redeployed with a troop of four guns at each of Kuala Selangor and Morib. Port Swettenham was defended by the MVF. A fleet of small boats full of Japanese troops attacking Kuala Selangor was repulsed by accurate gun fire with several boats sunk; air raids were experienced in Port Swettenham, but no land attacks.

Kuala Lumpur is about 30 miles from Port Swettenham and an enemy alert was given when the Japanese started to attack it on 6 January. The town fell on 11 January, but by that time the battery had withdrawn down the main north-south trunk road. It joined the rest of the regiment at Labis, but we were soon separated. The two batteries were used to support a retreat, again in leap-frog fashion down the trunk road.

At Gemas the railway from the east coast joined the tracks from the west coast, and with the Japanese advancing down both road and railway the positions on the trunk road could have been attacked from the rear. There a strong defensive position was established, with the regiment in support. We had started the war with the regiment in the 9th Indian Division, defending the east coast. With casualties in the 9th and 11th Indian Divisions the remaining troops were united in the 11th Division, and formed the force at Gemas.

The battery fired many rounds from this position, with one particularly bizarre action. The troop commander in his observation post (OF), underneath a bungalow on stilts, suddenly became aware of Japanese troops sitting round the post watching him. With presence of mind he ordered two rounds of gunfire on the OP. When the shells landed the Japanese ran for shelter, and he and his assistant OP gunner hastily escaped to the battery without being shot at. We were then ordered to retreat because there were now no infantry to provide covering fire for our position.

The whole division retreated down the trunk road to Yong Peng, while the battery was ordered to Rengam. Rengam is at the crossroads where the north-south trunk road is crossed by the road connecting Batu Pahat on the west coast with Mersing on the east coast; the distance between the two towns is about 80 miles. The plan was to establish a front line north of the Mersing road, using the road for communications between defended positions. The battery was ordered to find a position between Rengam and Kluang, a distance of about 20 miles, south of the road, and contact the Australian brigade which had been ordered to defend the road between these towns.

We searched, but could find no Australian troops, so extended our reconnaissance to Kluang, where we found a Sikh battalion, part of a brigade of the Indian army, defending the town. The Indian battalion was overjoyed to have artillery support, so we moved the battery along the road to Kluang. The next day the Sikhs were ordered to Nyior, and we accompanied them.

Nyior is a small village, just north of Kluang, on the railway line from Gemas to Singapore; the Japanese were advancing down the line to cut off Mersing. Our task was to prevent this manoeuvre by defending Nyior. The Sikhs and the battery advanced up the road from Kluang until the advance guard bumped into the enemy. Hurriedly taking up a position in the labourers’ lines of a rubber estate, the battery engaged the Japanese and their advance was halted.

Firing began at 1000 yards, but as the enemy advanced the range dropped until we were firing at 450 yards, which is getting rather close for artillery support. While we were firing at this range the platoon of Sikhs guarding the gun position intimated that the Japanese had infiltrated past the battalion and were attacking us in the rear. We led a bayonet charge from the battery position and drove them off. The Sikh battalion then mounted an attack and the Japanese temporarily retreated again.

The battery commander had been shot while directing gun fire from his OP, and was driven back to brigade headquarters. As the enemy outnumbered us the commanding officer of the Sikhs decided to withdraw. We later discovered that the Sikhs and ourselves had been fighting a full Japanese division.* The battery retreated down the road, but not back to Kluang because that area was under heavy attack; we were advised to aim for Johore Bharu, the town on the Johore Strait, at the Causeway joining Singapore island to the mainland.

During the night the battery made its way through a rubber estate at Layang Layang, getting lost because no maps showed the roads through this very large estate. However, by dawn on 30 January we arrived at Johore Bharu, and waited there to make contact with any army headquarters we could find. We did finally make contact and were ordered to cross the Causeway, go to the village of Woodlands and await further instructions.

Eventually, orders came through to go to the village of Ponggol on the north coast of the island and to establish a battery position there. Arriving at Punggol we found a zoo, surrounded by marshy land. It was pointed out to headquarters that no gun position was feasible, so off we were sent to the Tampinis road near Changi, still on the north coast of the island facing the Johore Straits. We still could find no infantry to support; reinforcements were expected, but were not yet in position.

Further orders then moved us to Tanjong Gul, a headland on the south west corner of Singapore island. There we found the 44th Indian Brigade; they had not formed a defensive position, so we did not prepare a gun position. Instead we formed a hide in a rubber estate, and waited for further information. When reconnoitring possible OPs and gun positions on 5 January I saw the convoy of reinforcements being heavily bombed while making its way to Singapore harbour.

On 6 January the battery itself was subjected to pattern bombing by the Japanese, with the bombs washing over the hide, like sea breaking over a beach. We had several casualties – lessened by effective slit trenches – but lost no guns or ammunition. There was still no information concerning enemy activity, or orders to prepare positions for defence. On the night of 8 February the Japanese attacked, landing in a marshy area near Kranji, a village on the north-west of Singapore island, north of our position.

The area around Kranji was defended by the Australians, and we heard the news of the landing on the Singapore radio on the morning of 9 February, but still received no orders. Listening to further Singapore news broadcasts, we heard that the Japanese had advanced to Bukit Timah village. To get back to Singapore town the battery had to go through Bukit Timah, and we now had no radio contact with all other formations.

It was decided that we would retreat to Bukit Timah between 9pm and 2am; the Japanese usually began operations at 4.30am every day. Driving at 5mph to reduce the noise of the vehicles, the battery inched its way along the road. The convoy drove through any Japanese positions – and also the positions of the British troops around Bukit Timah – and arrived safely about 3am, to everyone’s surprise.

We dug in gun positions east of Bukit Timah and looked for infantry to support; on finding infantry the battery fired a few rounds. The Japanese, as usual, succeeded in outflanking the position, and we were ordered to retreat to Buona Vista road to safeguard a river position, but on arrival we were instructed to retreat to Holland Road. Having found a suitable position, east of Holland Road, the area was reconnoitred and we came upon some armoured cars guarding a cross-road. They were about to retreat and the officer in charge advised us to get into Singapore city.

The battery hastily reformed on the road and drove towards Singapore, through Japanese troops taking up positions on one side of the road and British troops on the other. Luck held, and the battery, going about 50mph, escaped with only a few bullet holes through the trucks. Continuing on, the battery arrived at the sea front and took up a position on Beach Road, with the gun trails in the monsoon drain at the side of the road. A command post was established in Raffles Hotel, obliquely in front of the guns.

The British forces formed a perimeter around Singapore city in the shape of a semicircle, with both ends at the sea front. A battalion of the Malay Regiment defended a position at Pasir Panjang, a strip of land on the western end of the perimeter. This position had its back to the sea and stuck out of the perimeter like a long finger. In the afternoon the acting battery commander found the Malay battalion and offered support, which was gratefully accepted. The date was 12 February and it was late afternoon when the battery became heavily engaged with prolonged firing. In spite of repeated attacks the Malay battalion held firm and refused to withdraw from its position.

Friday, 13 February was a day of constant attacks, accompanied by heavy bombing and shelling. Water was running short in Singapore city as the reservoirs and the pipe line from Johore had been captured. By the morning of 15 February, Lieutenant-General Percival, the Commander-in-Chief of the Malayan Forces, had decided that further resistance was not possible, and negotiations for surrender were started.

The command was received by the battery that hostilities would cease at 4pm on the 15th, and at 3pm the last order was given for 43 rounds of gun fire on Racecourse Village. The ammunition was now completely expended so the gunners removed the nuts on the recoil mechanism of the guns; if the guns were fired they could explode. This task was completed just before the ceasefire.

The battery joined the rest of the regiment and settled down for the night of 15 February on the sea side of the Padang, the open space at the centre of Singapore. On the morning of 16 February the guns and vehicles were parked in a field near Tanglin, and the battery marched off to captivity at Changi, carrying whatever belongings we could manage on a twenty-mile walk.

The long march to Changi ended the first night at a small village, called Tanah Merah, where RAF personnel had been billeted. We went thankfully into the empty huts, with a lot of overcrowding, and settled down to sleep. The next day some food was organized and we looked at our surroundings – a village near the sea shore on the eastern side of Singapore island, about a mile short of Changi. The day passed uneventfully checking on all ranks to see whether the stragglers had arrived safely.

The next night was interrupted by some rifle fire and other explosions, making us wonder whether the capitulation had been completed. In the morning, after a meal, we explored the sea shore, not seeing any Japanese in the vicinity. At the other end of a shallow bay we saw a ‘bunch’ of Chinese, roped together, all dead. The bodies looked like a bundle of firewood, and appeared to have been machine-gunned while roped together. The corpses were lying against each other, some just off the ground, but most of them slumped down, some almost on their knees.

The Japanese hated – and feared – the Chinese, so had apparently lost no time in rounding up all those they suspected of being able to make some form of resistance. It was puzzling as to why these Chinese had been roped together before execution, but we presumed it was the quickest method of dealing with a mass execution. As we thought we could see Japanese soldiers near the dead Chinese, we decided a closer inspection was unwise.

With hands bound, and roped together, the Chinese would have been unable to escape the rounds from a machine gun; they could not run away, as they all faced in different directions. Those in the centre of the bunch were immobilized by those at the edge who had been killed first. One could imagine the thoughts of those in the centre of the group, when those on the outside were being shot, while they on the inside could do nothing to evade the bullets. As far as we could see from a distance, none were left alive. The tide was rising and lapping over the feet of those nearest the sea.

Shortly after this unpleasant experience the regiment was paraded and on its way to Changi, where we were imprisoned in Changi Gaol. The sight of the execution had raised doubts about our own fate; we could only guess at the reasons for the execution of the Chinese and feared the Japanese might deal with us in the same manner. As it turned out this was not the case, only POWs attempting to escape were in danger of execution when caught.

* Information from Japan’s Greatest Victory, Britain’s Worst Defeat, by Colonel Masanobu Tsuji, a senior Japanese staff officer. Published by the History Press.

Interlude

The description of the campaign in Malaya, and of my previous experiences, can be viewed through Western thought which has a set of rules for conduct, for both peace time and war time. Both British and Indian soldiers followed these rules. The ensuing description of life under the Japanese has to be viewed through Eastern thought, as explained below.

Whenever POW and Japanese are associated in British minds, the words ‘torture’ and ‘brutality’ are recalled by the majority of people. Torture implies the infliction of intense pain for revenge, cruelty, or to extract information; only the latter is really applicable to POWs, since the Japanese adhered to the POW conventions of the 1907 agreement. The Japanese had no need to interrogate POWs on military information, as it was no longer relevant. Escape was a subject for interrogation for the very few who attempted it, as the nearest friendly territory was either 2000 miles north of Thailand, or 3000 miles south, and none succeeded in reaching safety. Clandestine radio sets, and broadcast information, were the main object of POW interrogation, and members of signal units were prime subjects for questioning. For most POWs, however, interrogation was rarely seen, or heard of.

Brutality is subject to a wide interpretation, both historically and globally. In Britain, views on brutality have changed over the years; it is only just over 120 years ago that flogging in the British army was abolished, and Queen Victoria wondered how discipline could be maintained, as it was then considered a normal punishment. The Korean and Taiwanese guards were mainly responsible for any brutality suffered by POWs on the Burma-Siam railway, but the ill-treatment of Asian coolies working on the railway was far worse and has rarely been mentioned. The majority of British prisoners in Thailand came from 18 Division, whose troops had no experience of Eastern thought and customs, so judged their treatment by Western standards. This is probably the reason why brutality has been the subject of much sensationalism.

No Japanese soldier considered surrendering, as if he did, he could no longer return to his town or village and maintain his honour. The number of Japanese taken prisoner was very small and, in 1945, many Japanese soldiers were doubtful about surrendering, even though the Emperor had commanded it. This coloured the Japanese view of British POWs, considering such soldiers beneath contempt. The Japanese also held the Indian National Army (INA) in contempt as turncoats, and still hold the Koreans and Taiwanese in contempt as members of an inferior civilization, so all three were used as guards for the POW camps in a contemptuous gesture. The INA were used as guards in Changi, and rarely interfered with POWs. The Koreans and Taiwanese were ill-treated by the Japanese and passed on the treatment to the prisoners. Few Japanese soldiers had contact with POWs in Thailand, and had even less contact in Changi.

The outlook of people in Asia differs from that in the West, because the East deems the community more important than the individual. The standing of an individual in a community is determined by an Asian quality best translated as ‘face’. To lose face is to lose respect and attract contempt in a community. When a Japanese soldier slapped the face of a Korean guard, the action was not a physical punishment, but a cause of a loss of face in the presence of POWs. To attempt to regain face, the guard had to demonstrate his superiority over the POWs by a brutal act on more than one POW. Such brutality was not particularly aimed at an individual, but at the community of POWs. At all cost, whatever the action, an Asian must preserve face.

The Chinese have a proverb: ‘ride tiger, no dismount’, best rendered into English as ‘He who rides the tiger can never dismount’, and this was very applicable to the situation in South East Asia. Britain rode the tiger all over the East, from India to China, but dismounted when Singapore fell. There was a gleeful Asian reaction to Singapore’s collapse, and the normal Eastern reaction to a defeated opponent is to kick him hard when he is down, i.e. the tiger’s revenge. There was a strong element of this reaction in the Asian treatment of European prisoners, a point not always noted in contemporary thought. This reaction surfaced in the Dutch East Indies, when the Japanese, after the surrender at the end of the war, told the Indonesians that Asians had defeated Europeans, so continue the struggle. The result was the formation of Indonesia, as the Dutch were too weak to combat an insurrection. Not hitting an opponent when he is down is considered a sign of weakness in Asia.

The description of POW life in Thailand that follows has not emphasized, or drawn attention to, the treatment of POWs, as it is necessary to bear in mind the above observations when forming an opinion on brutality and torture said to have been inflicted on POWs in S.E. Asia. Civilians are not included in the description of captivity, because their treatment by the Japanese has been described in other books.

* * *

The country now called Thailand was known before World War II as Siam. In the book either term has been used depending on the circumstances, to describe factual events in what was Siam. The people are always referred to as Thais.

CHAPTER I

We say welcome to sunny Singapore

In Changi, after three moves in a week, the regiment settled into army huts in the prison camp, and remained there for the next six months. The time passed very slowly.

As the regiment maintained military discipline, the colonel decided that the Regimental Mess should have a proper mess night, once a week. Thursday was chosen for the night and officers from other units were invited, on a scale of four guests per week for the colonel, two per week for majors, one per week for captains, and one per month, if they were lucky, for subalterns. The Japanese gave a ration of 10 cigarettes per week to each officer, and one cigarette had to be handed in to form a prize for mess night. After dinner we played whist, usually with fancy rules, to see who would get the prizes. Many enemies were made by rash play – with 20 cigarettes at stake for the first prize.

I had a major part to play in this weekly fun, as I was Mess Secretary, and had to devise special dishes from the somewhat limited rations. The regiment had a wood party, consisting of an officer carrying a flag announcing the fact we were POWs seeking wood for fires; I always went on this wood party, trying to find anything edible that would improve the mess dinner. The party had the usual stripped-down lorry chassis, hauled by a dozen men; whilst collecting wood I looked out for food. On one trip I saw a tree with fruit in the shape of a bean, so I took a specimen, cut it open, and decided it was tamarind. When I returned to the camp, I looked up Corner’s Wayside Trees of Malaya to confirm that it was, having studied the leaves and fruit, indeed, a tamarind tree. Tamarind is a dark brown, fleshy pulp with a tart, fruity taste. On the next trip, we picked enough fruit to form a pudding, and the cook went into ecstasies at the thought of a tamarind tart. The tart was duly made and served with a flourish at dinner.

Everybody in the Mess enjoyed it, and the colonel said: ‘Damned good tart, that: haven’t enjoyed a tart so much for a long time. Good show.’ The evening was a great success, although I had a partner whose attempts at whist were abysmal, and no cigarettes came my way.

About midnight I awoke with a ghastly stomach ache, and made a quick dash for the lavatories. There I fell in behind the colonel and all the officers from the Mess. The colonel said, tersely: ‘That damned tart, find out what it was.’

The next wood trip found me searching for the tree, which I located and collected fruit and leaves. I took these to Southern Area, where the local Volunteer Units had people who had been members of the Agricultural Department in Malaya. I showed them what I had collected, and they eagerly inquired whether I could supply the camp with more of the fruit. I said I could but why did they want it? They replied that the hospital would require a lot; it was cascara, a good old-fashioned purgative. I wondered what the Mess would think when they found that they had been fed on cascara, but at least the doctors were happy. I did find out, also, that it required an expert botanist to distinguish between tamarind and cascara, so that put my mind at rest.

The dull, uneventful camp life was broken one day by the new Japanese commander, General Fukuye Shimpei, announcing that all ranks had to sign an undertaking that they would not escape. This was contrary to the international code for prisoners of war, and all ranks were told to refuse the Japanese order. When the General was told of the refusal he took action which surprised the camp. We were ordered to pack up our belongings, load them on to our wood-collecting trucks and march to an army barracks about a mile away. This was Selarang Barracks, previously used to house a battalion of British troops, but now all the POWs were packed into the one barracks. This consisted of a hollow square, with buildings around three sides of the square, which before had been the parade ground, covered in tarmac, for the battalion.

A road ran round the barracks, and our trucks were left on the other side of the road, while we were made to enter the barrack blocks. Japanese guards covered the road with machine guns, so that once separated from the trucks we could not go back to them. In the buildings, which had three storeys, each person was allotted a small space, about five feet by one and a half feet, hardly enough room for sleeping. The first necessity was the provision of lavatories, and these were dug as holes off the parade ground, with a rough cover, in some cases, of a canvas screen. Very soon queues formed and as time wore on it took about half an hour to work through the queue to a lavatory. One always seemed to get on the slowest queue, and there was much rude muttering. One private remarked, as he was retiring behind a screen, that he wished his sergeant-major could see him now – he had always wanted to do just that on the parade ground.

Food, of sorts, was made available, but conditions slowly became intolerable. The Japanese repeated their demand, but it was again refused. After a day or so the Japanese threatened that if we did not sign, the space we occupied would be halved every day. After a lot of consultation and as symptoms of illness became apparent amongst the prisoners (an outbreak of diphtheria), a decision was taken to sign, emphasising that the signatures had been made under duress. This was done, and thankfully we returned to what had now become the luxury of our old huts.

About the middle of summer 1942 an event occurred that gained the regiment a certain amount of notoriety. On a very ordinary day a fatigue party was called to fall in under the command of the sergeant-major. An altercation took place on the parade, although the origin of the words that started the event did not seem entirely clear to the rest of the regiment. However, the sergeant-major reported to the duty officer that the men were refusing to obey a command. This was passed on to the colonel, who decided that an incipient mutiny was threatened and after that events moved fast.

Most of the regiment were completely unaware of what had happened and what was happening. The colonel called for a court-martial, and one was duly convened. Rumours reached us but we had no firm information. The court-martial was held and some of the men who had been on that parade were judged guilty of disobeying a lawful order. Varying sentences of imprisonment were imposed and quickly promulgated. The regiment fell in on parade in a hollow square, the sentences were read out, and the prisoners marched off under an escort of military police. As far as we knew the police formed a military prison inside the POW camp, and the prisoners served their sentences there. To anticipate the remainder of this story, when we returned from Siam there was no trace of the military prison, and no news of the fate of the men – no information on the subject at all.

In October 1942 most of the regiment was transported to Japan and even farther afield, indeed one of my friends ended up working in a salt mine in Mukden in Manchuria. This left about 170 officers and men in Changi, and as time went on further small drafts were taken away and sent to other parts of the Japanese-occupied territories.

We, the final remnants of the regiment, had arrived in Changi village about the end of 1942. The date was uncertain for we had little means of marking the passing of time; every day was the same since Sunday had ceased to be observed as a day of rest. This was not abnormal because both the Chinese and Japanese use a month as the measurement of time and there is no equivalent of a week. The Chinese celebrate the second day of the second month, the third day of the third month and so on, a useful way to get work done. It eliminates the western weekend and the concept of a poet’s day.

We were now down to a strength of 80, the final remnants of the regiment, and were organized as a battery in our particular area.

* * *

It is evening and tranquillity is about to descend on Changi village. Twilight in the tropics lasts for only about ten minutes, going from full daylight to complete darkness in that time. Just before, during, and just after this period there is a hush in the world.

The air is perfectly still, smoke from wood fires ascends lazily and sounds appear magnified. A conversation at a normal level can be heard up to a quarter of a mile away and even further in the valley. There are no animal noises, the daylight contingent is settling down for the night and the nocturnal contingent has not yet woken.

A metalled road runs through the village, bordered on each side by a wide grass verge on which tall, leafy angsana trees are growing to give shade. Behind the verges, on both sides of the road, are several rows of wooden Chinese shophouses, spread out alongside the verges.

A shophouse consists of an open room with a concrete floor. The front is protected by a low wooden wall with posts supporting an upper storey in which are bedrooms for the shopkeeper’s family. Below, at the back of the shop, there is a concrete kitchen and wash place, the latter doubling as a lavatory. In the wash place is a square concrete tank, waist-high and tiled. The tank is filled with water from a tap and a dipper is used in bathing for throwing water over yourself.

At the back of the shophouses are several rows of coolie quarters – government property built of concrete with tiled roofs. In 1943 one of the shophouses was used as the battery office, sparsely furnished with only a table and a bench. The regiment had consisted of two batteries, whereas most regiments were organized into three batteries. Each battery had eight howitzers, guns capable of firing at a high elevation for low ranges to a target. The Changi office was the headquarters of the battery and it held all the records of pay, sick personnel, and the distribution of food; there was little else for which to keep records.

* * *

Peter Piper and I shared a coolie quarter. Peter was a lieutenant in a Jat battalion with the 45th Indian Brigade which was sent to defend the Muar River on the west coast of Malaya, part of the main defence of the State of Johore. The Japanese attacked down the river towards its mouth, while, at the same time, sending a force in small boats along the coast to attack the rear of the defensive position. After confused fighting the brigade withdrew southwards and was reinforced by two Australian battalions.

The withdrawal took the brigade south to Batu Pahat, with a defensive position on the river by the town. This position was overrun by the Japanese, and the Indian Brigade destroyed. Peter, with a few Indian soldiers, escaped and made their way to Rengam.

At Rengam, the main north-south trunk road crosses the road joining Batu Pahat to Kluang, and to Mersing on the east coast of Malaya. In the Rengam area Peter met up with British troops, including our other battery, and retreated with them to Johore Bharu, and thence to Singapore. As there were no other surviving officers of Peter’s battalion, he joined our regiment in Changi, and finally came to Changi village with me.

* * *

In the twilight of the evening we used to sit on the porch where we had a couple of chairs and a kerosi panjang