Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

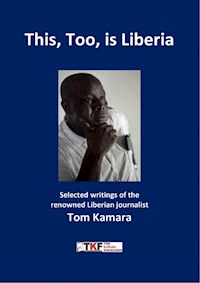

"This, Too, is Liberia" The above quote of the late Tom Kamara is emblematic for his writings and a characterization of the social, economic, and political landscape of his motherland. He fearlessly and objectively fought to expose the ills of the Liberian society. Tom was committed to promoting press freedom, social justice, and good governance in his beloved country and he did that even at the peril of his life. T.K., as he was affectionally called, did not only articulate the plight of the ordinary Liberians but devoted his life to the search for realistic solutions to the problems confronting Liberia. He wrote hundreds of articles in the New Democrat, the Liberian newspaper he founded in 1993, and in The Perspective, an online Liberian magazine, during his asylum in the Netherlands. This, Too, is Liberia contains a selection of his articles, with particular focus on Charles Taylor, the Liberian Civil Wars, the troubling relations between Liberia and the USA, the Samuel Doe and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf eras and the development of democracy in Liberia and other African countries. The book also includes three articles about the life and work of Tom Kamara. 274 pages - colour photos - maps

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 488

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This, Too, is Liberia

TitelseiteAcknowledgementsMapsIntroduction Tom Kamara (1949-2012)Section A: The Doe Era 1980-1990Section B: The Taylor Era 1990 – 2003Section C: The Johnson Sirleaf Era 2006-2012Section D: Liberia and the USASection E: Miscellaneous ItemsSection F: Reflections on Tom Kamara and his WorkSourcesList of AbbreviationsIndexCopyright© 2021 Tom Kamara Foundation / Rachael Kamara

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an automated database, or made public in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Editor: Leo Platvoet

Maps: Nel de Vink (DeVink Mapdesing)

Printing: Patria – The Netherlands

Photos: Leo Platvoet: page 22, 28, 38, 46, 53, 57, 61, 69, 72, 74, 81, 85, 92, 103, 113,136, 164, 179, 216, 230, 239, 245, 257.

Collection of Rachael Kamara: cover, page 247, 250, 252, 255.

All other photos are license-free as far as we have been able to ascertain. If this is not the case, please send an email to the Tom Kamara Foundation. The websites mentioned in the footnotes have been accessed on November 29, 2020.

SBN 9789461231321

The printing of this book has been partly sponsored by Odyssee Travel Guides.

Published by the Tom Kamara Foundation

E-mail: [email protected]

About the Tom Kamara Foundation

The Tom Kamara Foundation was established in June 2013 in memory of Tom Kamara, who was the publisher of the Liberian newspaper theNew Democratuntil his death in 2012.

The Mission of the Tom Kamara Foundation is:

To foster, promote, sustain, and improve professional journalism in Liberia and Africa.

To provide support for journalists engaged in rigorous, probing, spirited, independent and critical work that will benefit the public.

To support journalism and foster a community of journalists engaged in truthfully informing the public.

To promote professional journalism, primarily in areas of investigative reporting, youth education, professional development, and special opportunities.

Acknowledgements

This book includes a selection of 53 articles, written by the late Liberian journalist Tom Kamara. He wrote these articles between 1997 and 2012. The articles were published in The Perspective1, an online newsmagazine published by the Liberian diaspora in the USA, and the New Democrat, the Liberian newspaper Tom Kamara founded.

The idea to publish this book came up after the launch of the Tom Kamara Foundation in 2013. The widow of Tom, Rachael Kamara, Jimmy S. Shilue and Leo Platvoet committed themselves to this task, but lack of time and funding took some time before this idea became reality.

The main reason for the publication of this book is that there are hardly available accounts (firsthand or eyewitness) of recent history of Liberia, written by Liberian authors. We hope that this book will be read by students, scholars, teachers, politicians, journalists etc., so knowledge and understanding of the recent history of Liberia will be the guide to a better Liberia.

We had to choose out of 138 articles that were available to us. Undoubtedly, Kamara has written far more articles in the 40 years he used his sharp pen as a weapon for justice and democracy, but archives of newspapers he worked for in the 1980s like The Liberian Star and The New Liberian are not existing.

The archive of the New Democrat is, due to several actions of Charles Taylor fighters in 1996 and 2000, also very incomplete (see Section F - D). This is why The Perspective is a valuable source for this project, although many of these articles have also been published in the (digital) version of the New Democrat.2

With the selection of the articles, we show the broader scope of Tom's writings: not only about the Liberian Civil War, but also about other topics.

The book starts with an introduction to the life and work of Tom Kamara.

The selected articles are divided in five sections:

The Doe Era (1980-1990);

The Taylor Era (1990-2003);

The Johnson Sirleaf Era (2006-2012);

Liberia and the USA;

Miscellaneous Items.

Section F includes reflections on the life and work of Tom Kamara.

The detailed index makes it easy to search for names, events, and places.

The copyrights of the selected articles are in the hands of Rachael Kamara. The copyrights of the other articles (Introduction and Section F, B and C) belong to the authors of these articles.

The introduction (in italics) of each of the 53 selected articles, as well as the notes included in these articles have been written by Leo Platvoet.

The notes aim to give more information and historical context about persons and events. The books that were used as a source for this are listed in the Sources chapter.

In a boxed text on page 145 you will find information about the Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In a number of articles one or more paragraph(s) of the original text is / are not included in the text of this book. The only reasons for this are the following two.

1. It is a repetition of something that is mentioned earlier in an article in this book. Tom Kamara knew of course that repetition is an important way to make his cause, especially when there is a time gap between the publication of two articles about the same subject. But in a book, this is less expedient.

2. The topic Tom addressed is too far away from the original scope of the article – that could distract the reader's interest to read on.

The place where a paragraph is deleted, is marked with (…).

Tom Kamara was critical because he loved Liberia. He wrote about the many sides of the first African republic, often saying loud 'This, Too, is Liberia'.

Rachael Kamara

Leo Platvoet

Jimmy S. Shilue

In 1996,The Perspective online newsmagazine was created by George H. Nubo, Siahyonkron Nyanseor and Abraham M. Williams. As soon as Tom heard about it, he joined them, contributing many articles. For a partial list of his articles on ThePerspective.org website, see at the bottom of A Tribute to Thomas "Tom" Saah Kamara: My Comrade in the Liberian People's Struggle for Rice & Rights by Siahyonkron Nyanseor, in: The Perspective, Atlanta, Georgia, June 22, 2012, https://www.theperspective.org/2012/0622201201.html. For the Tribute itself: see Section F - C.

The digital version of theNew Democrat is no longer online. However, you can view on the internet archive WayBack Machine a number of digital New Democrat issues, published between 2005 and 2020, see: https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://newdemocratnews.com/

Maps

1: Liberia, West Africa, Africa

2: National capital Monrovia, the 15 counties of Liberia and their capitals

3: Language and ethnic groups

Introduction Tom Kamara (1949-2012)

By Fred van der Kraaij

PART I: Remembering Tom Kamara

It was with dismay and disbelief that I learned about the tragic passing away of Tom Kamara, in a Brussels hospital on June 8, 2012. Tom was on his way to the Netherlands, his second homeland, when he collapsed in the airplane that brought him from Monrovia to Brussels. When we separated in Monrovia, the previous month, we had agreed to meet again in the Netherlands. However, fate decided otherwise. We would never meet again. He was 63 years old when he traveled to the great beyond. Liberia lost with him one of its most illustrious journalists, a fighter for press freedom, human rights, justice, and democracy.

Tom Kamara Tom Kamara, a Kissi-Liberian, hailed from Lofa County, where he was born in 1949 in the small village of Sodu, in the Foya chiefdom. He impressed at an early age with his writing skills. During the Administration of President William Tolbert, Jr. (1971-1980) he contributed as a reporter to The Liberian Star, then one of Liberia’s main, privately-owned newspapers. After graduating from the University of Liberia (1970s) he studied journalism at the University of Texas. Upon his return from Texas in 1981, he became the editor of The New Liberian, a government-owned newspaper, but was fired after criticizing the Chairman of the People’s Redemption Council (PRC), Samuel Doe.

Tom Kamara was an independent intellectual, a fearless fighter for the ideals he believed in, and an uncompromising author whose sharp and sometimes polemical style brought him into conflicts with friends and foes, presidents, warlords and other powerful people. His criticism of Samuel Doe and his PRC led to his arrest by the National Security Agency in 1984, but he managed to escape from the secret police’s prison, just hours before he was to be summarily executed by Doe’s henchmen during his transfer to the notorious Bella Yella prison in western Liberia. I remember the article inThe New African, a leading magazine in those days, narrating his miraculous escape. Tom described his escape from death in a 2001 article entitledOrdeals & Pretenses1, published in the Liberian online newspaper The Perspective.2

In 1985 Tom Kamara was in Accra, Ghana, where he and a friend, the political activist James Fromayan3, were in close contact with Charles Taylor and his then girlfriend, later his wife, Agnes Reeves4. Earlier that year, Taylor had escaped mysteriously from an American prison, fleeing to Rawlings’ Ghana with the help of Boima Fahnbulleh5, a good friend of President Jerry Rawlings, before continuing to Gaddafi’s Libya. To avoid any misunderstanding: neither Tom nor James shared Taylor’s political ideas or were associated with his plans and undertakings. The foregoing merely illustrates a major characteristic of the Liberian political system: the country’s important actors know one another well. In the second half of the 1980s when travelling to his brother in the United States Tom made a stopover at Schiphol Airport in the Netherlands where the police arrested him for travelling on a fake passport. Two Dutchmen, Jacques Keiren and the Roman Catholic priest Geert Bles, who happened to be very familiar with Liberia, testified on his behalf and identified him as Tom Kamara, showing the New African article about his narrow escape from Doe’s henchmen. They convinced the Dutch authorities that Tom would be killed if sent back to Liberia. Hence, Tom was granted political asylum. The Netherlands became his new home. Here he would make many friends. With intervals he spent eight years in the Netherlands, notably with Jacques and his wife Hermien Keiren, in the hilly hamlet of Trintelen, in the southern province of Limburg. Tom and his wife Rachael were familiar with Trintelen, the 152 inhabitants of the tiny hamlet were familiar with the couple. After President Samuel Doe had been tortured to death in September 1990 by Prince Y. Johnson6, one of the warlords who brought havoc to the capital and the country, Tom returned to Monrovia, where he re-started the New Democrat. I was told the following by both Tom (Kamara) and James (Fromayan) when I met both men in Monrovia, in May 2012. Tom, James and some others were on Bushrod Island, near the Vai Bridge, when they met with Prince Johnson, leader of the Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL) – composed of Manos and Gios formerly belonging to Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) - who was moving towards downtown Monrovia. Prince Johnson, who was hostile to Tom and his independent newspaper, questioned them what they were doing in the area and wanted to kill them, but they managed to escape though while trying to escape Tom was shot in his leg and badly wounded. He would never completely recover. Immediate treatment in Monrovia was not successful due to the lack of qualified medical personnel. Tom was evacuated to the Netherlands for further medical treatment, but the damage caused by the lack of immediate effective medical treatment was irreparable. He was hospitalized for many months in the Netherlands, followed by a stay with his Dutch friends in Trintelen for further recovery. In 1993 Tom and Rachael again returned to Liberia. Tom briefly served in the government of Interim-President Amos Sawyer7, a close friend of his, but they split-up due to policy differences. The word ‘compromise’ did not exist in Tom’s vocabulary. Aided by Dutch friends the New Democrat had another re-start, with new offices. Soon the New Democrat became one of the most popular and most informative newspapers in Liberia. Tom’s independent writing and criticism brought him into conflict with NPFL rebel leader Charles Taylor. During the ‘Third Battle of Monrovia’, in April 1996, NPFL rebel forces set the offices of the New Democrat on fire. After Charles Taylor was declared the winner of the 1997 presidential elections ("He killed my ma, he killed my pa, but I voted for him", Liberians said, fearing a flaring up of the war if Taylor would not win the elections), the harassment of Tom and his newspaper team by Taylor’s forces continued unabated, it even got worse. In 2000 the Taylor Administration shut down the newspaper and Tom’s life was threatened. Tom had to flee again – he was a prime target on Taylor’s hit list. Tom again went into exile, first to Ghana then to the Netherlands where he started an online edition of his newspaper. After Taylor’s forced exile (2003), in 2005, Tom and his wife Rachael returned home where Tom continued his work for more democracy, more justice and more press freedom. The New Democrat was again printed in Liberia, albeit with Dutch financial support. One would expect that during the Administration of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (2006-2018)8, who strongly advocated freedom of the press, Tom’s work in Liberia would be smooth sailing. The reality was different. In 2010 the New Democrat’s website was brought down by hackers twice in one month time. The government brought multi-million-dollar libel suits against the newspaper following reports on corruption by government officials. Even President Sirleaf once wanted to sue him, Tom told me in his Clay Street office on May 9, 2012, but he convinced her that he had used official sources for a publication that she disliked and the libel case was called off. Their relationship certainly was strained which though did not prevent him from contacting her occasionally by telephone, he emphasized. He was a true journalist, without any fear, independent, not ready for compromises and avoiding conflicts of interest. In February 2012, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf appointed Tom Kamara as a member of the Board of the National Port Authority, an appointment that stirred much debate. Typically for Tom, he declined the offer that very likely would have been accompanied by an interesting monthly check.

On March 1 he thanked the President, adding: "Kindly permit me to extend my humble appreciation to you for appointing me as a member of the Board of Directors of the National Port Authority. However, due to my current busy responsibilities, it is my courteous regret to inform you, Madam President, of my unavailability this time to serve in this position."

Tom Kamara could not be bought. Yet, despite the clashes and criticism, there were no hard feelings. When President Sirleaf learned about Tom’s unexpected passing, the Executive Mansion issued a press release informing the nation that "President Sirleaf has learned with deep sadness the passing of iconic journalist Tom Kamara (…), a great patriot who dedicated his life to the pursuit of freedom of speech, the right of the media, and the democratic process in Liberia and in Africa.”

President Sirleaf stated that “Mr. Kamara has earned a special place in the hearts of many Liberians (and that…) Liberia has lost one of its greatest sons (…). Tom Kamara was a good friend and will be missed by the entire nation."9

Tom Kamara has been compared to the late Albert Porte, another great Liberian journalist who was fearless, a brave soldier whose only weapon was a pen – not an AK-47 – and who never missed his target. Tom’s uncompromising stance and polemic, provocative style brought him in conflict with the authorities. They threatened him, sued him, and put him in jail and on their death list. But Tom never succumbed to pressure or temptation. The fear and hate of dictators and warlords Samuel Doe, Charles Taylor, Prince Johnson, George Boley, Alhaji Kromah and the likes of them only fed his courage and determination to fight for human rights, democracy, and social justice. Tom Kamara was laid to rest in Brewerville outside Monrovia on Saturday, June 23, 2012. He has gone to the great beyond, but his thoughts and articles remain with us.

PART II: The selected writings of Tom Kamara

The book before us contains a selection of his articles, published in The Perspective and the New Democrat in the 1997-2012 years.

The series of articles starts with the Doe years. With hindsight, the PRC coup of April 12, 1980 which brought Master-Sergeant Samuel Doe, a Krahn-Liberian, to power was the prelude to two devastating Civil Wars. The PRC coup ended the hegemony of a small elite of Americo-Liberians - i.e. the descendants of the African American colonists who proclaimed the independence of Liberia in 1847 - and was acclaimed enthusiastically by the majority of the indigenous people. However, PRC Chairman-turned President Samuel Doe replaced one minority rule by another, favoring his fellow Krahn people and a group of supportive Mandingo-Liberians. The ensuing armed reaction of ambitious politicians who relied on their tribal base in the struggle for power and the supreme price, the Executive Mansion, escalated into a pointless, ruthless, insane and cruel Civil War. The first Civil War was ignited on Christmas eve 1989 by the NPFL. The NPFL invasion from Ivory Coast into Nimba County was supported by Burkina Faso’s Blaise Compaoré, Ivory Coast’s ‘old man’ Houphouët-Boigny, and Libya’s ‘Colonel Gaddafi’. The war raged from the Christmas incursion until the ‘election’ of warlord Charles Taylor as Liberia’s President in 1997. Neighbouring countries Guinea and Sierra Leone became involved in the second Civil War (1999 – 2003) which only ended with the Comprehensive Peace Treaty signed in Accra, Ghana en the forced resignation of warlord-turned-President Charles Taylor. After two Civil Wars, the country was devastated, the economy in ruins, an estimated 250,000 people had been killed – sometimes savagely – and many more traumatized. The violent conflict in Liberia had rocked West Africa and notably its most important regional organisation ECOWAS to its foundations.10 In 2006, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was entrusted with the two difficult tasks of rebuilding the country and its economy and reconciling the various parts of its population. It was in the context painted above that Tom Kamara wrote his articles for the New Democrat newspaper (and The Perspective online magazine). The bulk of the 53 articles selected here cover the Taylor era, one of the darkest – if not the darkest - in Liberia’s history.

Charles Taylor’s escape from a Plymouth County jail (Massachusetts, USA), in 1985, is still surrounded by mysteries. I heard him testifying before the Special Court for Sierra Leone (The Hague, 2009) that he ‘escaped’ by walking through the front door of the maximum-security prison where he was met with American secret agents who drove him to a safe spot from where he traveled to West Africa. A fantasy, a lie or did it really happen? Was he put on the CIA or Pentagon payroll and sent to spy on ‘Colonel Gaddafi’ nicknamed ‘Mad Dog’ by USA President Ronald Reagan? Both Tom Kamara and James Fromayan independently confirmed Taylor’s version of his ‘escape’ when I spoke to in May 2012. In the article In Search of Enemies and Allies (2000, No. 11), Tom Kamara shows his gift of observation and his analytical skills, writing: "Since he assumed office, Taylor has been dancing between Tripoli and Washington. Tripoli may have helped him to destroy the country, but as he sees it, he needs Washington to build it." But the Americans did not support Taylor (anymore?): they were disappointed in the man who had proved to be unreliable and a criminal, who stirred up a cruel civil war in Sierra Leone in exchange for ‘blood diamonds’, who meddled in other West African countries, and who had become friends with arch-enemy Muammar Gaddafi and Al Qaida terrorists.

The articles covering the Taylor era are a sharp reminder of the horrifying terror of Charles Taylor and his henchmen who turned Africa’s oldest republic into a gangster paradise where no law existed unless the law of the jungle. Noteworthy in this respect are the articles Liberia’s Persecuted and Rising Voices of Dissent (2000, No. 12) and Liberia: The Emergence of a Criminal State (1999, No. 17). However - notwithstanding the foregoing - mentioning specific articles does not do justice to the other articles which are as sharp and to the point as the two cited. Tom Kamara not only severely criticizes Charles Taylor and the other tropical gangsters, most of whom are still at large, whereas some even enjoy a lavish lifestyle in Monrovia or elsewhere in Africa. In ‘The Curse of Mercenaries’ (2000, No. 23) he attacks mercenaries, arms traders, murderers and other criminals, most of them partners-in-crime of Charles Taylor: Foday Sankoh, the notorious Sierra Leonean RUF leader, Blaise Compaoré, President of Burkina Faso, the Ukrainian arms dealer Leonid Minin, the Dutch timber baron Guus Kouwenhoven aka ‘The Godfather of Liberia’ and, closely related to the latter, Emmanuel Shaw, an opportunistic, unscrupulous confident of Samuel Doe and his Finance Minister in the 1980s, and Ambassador-at-Large and financial advisor under Charles Taylor.11 Besides, it’s interesting to note that Emmanuel Shaw is now a Senior Advisor to President George Weah.

The articles focusing on Taylor’s misdeeds, war crimes and human rights violations – impossible to list them all here - are to the point and devastating. They constitute painful reading since they bring back bad memories of a gruesome and senseless period in the history of Liberia, a country which was created for the love of liberty and a better life.

Tom Kamara also targets non-governmental organisations operating in Liberia (in:Pariahs, Sanctions, versus “Ordinary People”, 2000, No. 15) as well as West African Presidents and African leaders in general: Abacha, Compaoré, Houphouët-Boigny, Jammeh, Gaddaffi, Kabila, Mobutu, Savimbi (in: Misinformation, Sanctions and Bedfellows, 2001, No. 25). Neither does he speak favorably about two foreign emissaries, Rev. Jesse Jackson (The True Face of Rev Jackson’s Liberian heroes, 2000, No. 36) and Jimmy Carter (Carter’s Sad Liberia Good-Bye, 2000, No. 42). In the article Misinformation, Sanctions and Bedfellows he warns that Taylor constitutes a threat to the entire West African region because of diamond smuggling, depletion of tropical forests, illegal arms trafficking and armed conflicts which cause tens of thousands of people to desert their homes and to flee to a safer place. Charles Taylor, a bragger, was serious when he said: "Give me ten years and I will control the region." 12

Tom’s doesn’t limit his critical views and analyses to the Liberian context. InElections and Erosion of Stability in Africa (2000, No. 46) he casts a critical eye on the multi-party election process in Sub-Saharan Africa. The implosion of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin Wall heralded a new era for the ‘Third world’ including Africa since it meant the end of the ‘Cold War’, characterized by a rivalry between the two super-powers, the United States and the Soviet Union. However, the transfer of one-party states to multi-party democracies was and is not an automatic and smooth process, as Tom outlines in the article cited. Generally speaking, in Sub-Saharan Africa we may distinguish three types of ‘elections’: (1) elections by ballot, (2) ‘elections’ by bullet, and (3) ‘voting with your feet’, i.e. joining the Diaspora abroad (see his Opting for Refuge over "Honour", 2000, No. 38). Tom shows his excellent knowledge of developments on the African continent in African Union or African Utopia (2001, No. 49) impressing and entertaining us with a bird’s eye view of African affairs. In Here Comes the Shantytown Democracy in The Legislature (2011, No. 33) he shows both insight and foresight when drawing attention to the high urban population growth rate at the expense of an increasingly marginalized rural population, forecasting "He or she who must be president or in the legislature, in the coming years, must be the accepted king or queen of the shantytowns." The Congress for Democratic Change (CDC) led by George Weah would not win the 2011 elections, but in 2017 George Weah’s Coalition for Democratic Change (an alliance of CDC, NPP and LPDP) won the presidential elections, thanks to the massive support of young voters from Monrovia’s slums, coined ‘shantytown clientele’ by Tom. The unemployed urban youth with no or few perspectives adored their hero, the former international football player now a politician, George Weah, who grew up in Claratown, one of Monrovia’s largest slums.

Selling Democracy As An Endangered Demon To The Poor (2012, No. 35) was Tom’s last article before he passed away. In this article he writes a devastating criticism of the ‘elected thieves’ in Liberia. Here and in another selected article (The Second Term Curse Looks On, 2012, No. 34) we find him surprisingly mild towards President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

In general, Tom was highly critical about the events, policies and persons he describes. Critics of his writings point to the fact that he rarely provides us with an alternative or a solution for the problems described. Some people find him too critical or unjustly harsh – and at least undiplomatic – in his articles. The truth is that the very concept of ‘truth’ is a difficult one. It reminds me of an old catchphrase, attributed to the Irish poet Oscar Wilde: "The truth is rarely pure and never simple".13

Rare are the articles in which Tom praises someone. I must mention here two examples. InWoes of the African Journalist (2001, No. 50) he rants about western hypocrisy but lauds the Liberian academic, activist and politician Togba-Nah Tipoteh14. In his article Rawlings remembered (2000, No.47) he is positive about Jerry J. Rawlings who led Ghana for over 20 years, first as a junta leader, thereafter two terms as the country’s democratically elected president (1981-2001). Flight-Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings died from Covid-19 in November 2020. Retroactively, Toms’ article on J.J. Rawlings is a worthy tribute to an outstanding albeit controversial statesman.

Tom Kamara was not a saint either. In general, journalists are not always the nicest people; their drive to write is not to be found agreeable - on the contrary, journalists who want to please create distrust. Their relations with the persons described are often far from smooth because of a spicy pen. Notably Tom’s pen could be very spicy - not surprising for a journalist from the former Pepper Coast! Tom combined an honest disapproval or even outrage with an intense feeling and conviction that he had to raise his voice against social injustice, oppression, exploitation, hypocrisy, discrimination, the lack of press freedom and the violation of human rights. Often this meant walking a tight rope. Tom experienced the wrath of oppressors whom he criticized but he was determined and uncompromising. Moreover, he was incorruptible. Altogether this makes him irreplaceable. Tom, Rest In Peace.

Print screen of the website of The Perspective

About the author:

Dr. Fred van der Kraaij is a Dutch economist. Since 1975 he has been following political events and economic development in Liberia, where he taught economics (University of Liberia, Monrovia). His PhD dissertation was on Liberia’s Open Door Policy. He twitters as @liberiapp and maintains the website ‘Liberia: Past and Present of Africa’s Oldest Republic’ www.liberiapastandpresent.org. He is the author of Liberia: From the Love of Liberty to Paradise Lost (2015). In this book, a personal account, he looks back on the country he has grown to love.

‘Ordeals & Pretenses’, The Perspective, April 3, 2001, see https://www.theperspective.org/ordeals_and_pretenses.html. Section F - C: A Tribute to Thomas 'Tom' Saah Kamara includes Tom's story of his escape.

See note 1.

James Fromayan was born in 1950 in Zorzor, Lofa County. He was among a group of progressive students at the University of Liberia whom I taught economics in the 1970s. In the 1980s, he went to the Netherlands where he obtained an MA Degree in Politics and Development Strategies from the Institute of Social Studies (ISS). During the Interim-Presidency of Amos Sawyer (1990-1994) he served as Minister of Education whereas President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf made him Chairman of the National Elections Commission (NEC), responsible for the preparation and the smooth conduct of the 2011 presidential elections.

In 2017, Agnes Reeves Taylor, ex-wife of Charles Taylor, was arrested in the UK and accused of torturing political opponents in the 1989-1991 period. After torture charges against her were dismissed in 2019, she was set free. In July 2020 she returned to Liberia where she received a rousing welcome by stalwarts of the NPP party, the political party created by her former husband.

In the 1970s, Boima Fahnbulleh, a Vai-Liberian, was among a group of four prominent political activists including Amos Sawyer, Togba-Nah Tipoteh and Dew Mayson, belonging to one of Liberia’s oldest grassroots organisations, the Movement for Justice in Africa (MOJA, see also note 138). He was a University of Liberia professor, Minister of Education (after the 1980 PRC coup) and, much later, President Johnson Sirleaf’s advisor on national security.

See note 45.

Amos Sawyer is an outstanding academic, a political activist and a well-known politician. He has a mixed ethnic background. His mother, a Sarpo-Liberian, grew up with an Americo-Liberian family, his father was born in Sierra Leone and came to Liberia at an early age. Amos Sawyer was co-founder of MOJA, University of Liberia professor and Dean of the Political Science Department, and research scholar at Indiana University (USA). In 1984, he headed the National Commission mandated by Samuel Doe to draft a new Constitution, but he declined an invitation of the PRC chairman to become his Vice President. Amos Sawyer was Interim-President of the Interim Government of National Unity (1990-1994), founder and Executive Director of the Center for Democratic Empowerment (CEDE) and was appointed Chairman of the Governance Commission (GC) by President Sirleaf. For more details, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amos_Sawyer.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was Liberia’s first female, democratically elected President. She is an economist and an old hand in Liberian politics with a vast professional experience ranging from governmental positions – she was Minister of Finance under President Tolbert – to high-ranking positions in international banking and developmental organisations. She has a mixed ethnic background. Her father, who was raised in an Americo-Liberian family, was the son of a Gola chief whereas her mother, who also grew up in an Americo-Liberian family, was the child of a market woman from Sinoe County and a German trader. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s impressive personal life and professional career are well described in her autobiography ‘This Child Will Be Great’, (New York, 2009). In 2009, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended that she be barred from holding public office because of her association with the NPFL (thus blocking a second presidential term), but the Supreme Court ruled that this recommendation was unconstitutional. President Sirleaf acknowledged that she had made an initial financial contribution to the NPFL in its early years and apologized publicly for it. However, her political opponents including Charles Taylor and his right-hand man Tom Woewiyu contradicted her, asserting she played a much bigger role in the rebel group. See also note 50.

President Sirleaf Pays Tribute to Iconic Journalist Tom Kamara, Press Release, Executive Mansion, June 11, 2012, Monrovia, https://www.emansion.gov.lr/2press.php?news_id=2223&related=7&pg=sp.

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), created in 1975, was the first West African organisation including both anglophone, francophone and lusophone countries. Although basically an economic organisation promoting economic cooperation among its (initially) 15 member-states, the Liberian crisis led to an important military role (notably ECOMOG in Liberia), spearheaded by Nigeria.

A leading Dutch newspaper,Het Parool, reported in 1997 that a Dutch drug syndicate operated in West Africa under the protection of Charles Taylor and Emmanuel Shaw who shared in its profits. A Liberian fishing project, ‘West Coast Fisheries Ltd.’, served as a cover-up for the transshipment at sea of Pakistani hashish, loaded into several smaller fishing boats, before being transported to the final destination in Europe. Source: Operatie Laat Niets In Leven (in Dutch), translated: Operation No Living Thing – by Arnold Karskens & Henk Willem Smits (Amsterdam/Antwerp, 2018), pp. 80-90. For more details on Shaw’s dubious and illegal moneymaking, see His main occupation was stealing and Oil man’s CV of sleaze, https://mg.co.za/article/1997-12-19-his-main-occupation-was-stealing/ respectively https://mg.co.za/article/1997-11-14-oil-mans-cv-of-sleaze/. For Kouwenhoven see note 22.

More on Charles Taylor’s background, rebel years, presidency, exile, arrest, conviction, and sentence, see: http://www.liberiapastandpresent.org/TaylorCharles/index.htm.

From: ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ (1895).

Togba-Nah Tipoteh, a Kru-Liberian, is an outstanding academic and well-known Liberian politician. University of Liberia professor, co-founder and President of MOJA (see also note 138), founder and leader of Susukuu, Liberia’s oldest non-governmental development organisation, Minister of Planning and Economic Affairs (after the 1980 coup). In 1981, he was granted political asylum in the Netherlands after fleeing Liberia fearing being killed by Samuel Doe. He ran three times unsuccessfully for president (1997, 2005, 2011). He is admired for being the only presidential candidate who did not leave the country after Charles Taylor became president. For more details, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Togba-Nah_Tipoteh.

Section A: The Doe Era 1980-1990

Samuel Doe (1951-1990) served as the Liberian leader from 1980 to 1990, first as a military leader and later as president. While a master sergeant in the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL), Doe staged with a small group of soldiers a violent coup d'état in April 1980 that left him de facto head of state. During the coup, then President William Tolbert1, and much of the True Whig Party leadership were executed.2Doe then established the People's Redemption Council (PRC), assuming the rank of general.

Doe attempted to legitimize his regime with passage of a new constitution in 1984 and elections in 1985. However, opposition to his rule increased, especially after the 1985 elections, which were declared to be fraudulent by most foreign observers. Doe had support from the United States; it was a strategic alliance due to his anti-Soviet stance taken during the years of the Cold War prior to the changes in 1989 that led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The first native head of state in the country's history, Doe was a member of the Krahn ethnic group, a largely rural people. Before the 1980 coup, natives had often held a marginal role in society, which was dominated by the descendants of the Americo-Liberian settlers; composed primarily of free-born African Americans and freed slaves, they were the immigrants who had established Liberia in the 1820s and led the country beginning with independence in 1847.

In the late 1980s, as the USA government adopted more fiscal austerity and the threat of Communism declined with the waning of the Cold War, the USA became disenchanted with the entrenched corruption of Doe's government and began cutting off critical foreign aid. This, combined with the widespread anger generated by Doe's favoritism toward Krahns, placed him in a very precarious position.

A Civil War began in December 1989, when rebels entered Liberia through Ivory Coast, capturing and overthrowing Doe on September 9, 1990. He was tortured during interrogation and murdered by his conqueror, Prince Johnson, one-time ally of Charles Taylor, in an internationally televised display.3

1. Struggling Against The Sword

March 26, 2001

In this article Tom Kamara writes about the historical reality that from its inception, the Liberian state was built on brutality and exploitation, all in a crusade of politics as means of personal wealth. According to him Liberia has always been a state erected on violence and corruption, rewarding its adherents with beastly power and therefore material wealth in a sea of poverty and illiteracy.

The winds of intolerance raging over Liberia since its founding in 1822 by freed American slaves, continue to blow with devastating effects despite a coup d'état over 2 decades ago in the name of change, followed by a war of terror in the name of justice. "I came to get the dictator off the Liberian peoples' back," Taylor the ruthless, marauding warlord promised a decade ago. But the handwriting was all along on the wall, for even the blind, that he came to climb on the people's back for implanting a more debased tyranny. "I will sit there like a porcupine and see who will remove me," he clarified later.

And indeed, he has. The recent brutish armed assaults on students and teachers at University of Liberia indicate that certain things do not however simply change, and this includes an in-built value system of a people.

Successive Liberian regimes, adamant in their politics of exclusion and obsessed with theft and plunder as political gains, lived and ruled by the sword, and those who naively expected a departure from this value system under a man who reduced the country to utter primitive levels for the presidency, determined to win power by all means and at all costs, grossly showed their ineptitude in defying history and ignoring reality. As before, in this war against ideas opposed to totalitarianism, the University of Liberia remains a "legitimate military target." Its President Dr. Ben Roberts, a Taylor protégé and key participant in the war in which child soldiers died in their tens of thousands, decreed after the bloody assault that the University is not a "place for political agenda." He proceeded to "discipline" the students by suspending their leaders from studies, vowing to continue the purge of ideas in Taylor's name. But men like Ben Roberts defy history because his predecessors had used the same scripts of intolerance only to regret their war against ideas in the service of a myopic tyrant. He will be no different.

Entrance of the University of Liberia

Section B: The Taylor Era 1990 – 2003

Charles Taylor, born 1948 in Arthington, Liberia, is son of a Gola mother and either an Americo-Liberian or an Afro-Trinidadian father. Taylor was a student at Bentley University in Waltham, Massachusetts, USA, from 1972 to 1977, earning a degree in economics. After the 1980 coup d’état he served some time in Doe's government until he was fired in 1983 on accusation of embezzling government funds. He fled Liberia, was arrested in 1984 in Massachusetts on a Liberian warrant for extradition and jailed in Massachusetts. He escaped from jail the following year and probably fled to Libya. In 1989, while in Ivory Coast, Taylor assembled a group of rebels into the military wing of the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), mostly from the Gio and Mano tribes.

In December 1989, the NPFL invaded Nimba County in Liberia. Thousands of Gio and Mano joined them, Liberians of other ethnic background as well. The Liberian army (AFL) counterattacked and retaliated against the whole population of the region. Mid-1990, a war was raging between Krahn on one side, and Gio and Mano on the other. On both sides, thousands of civilians were massacred.

By the middle of 1990, Taylor controlled much of the country, and by June laid siege to Monrovia. In July, Prince Johnson split off from NPFL and formed the Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL), based around the Gio tribe. Both NPFL and INPFL continued their siege of Monrovia.

In August 1990, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), an organisation of West African states, created a military intervention force called the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) composed of 4,000 troops, to restore order. President Doe and Prince Johnson (INPFL) agreed to this intervention, Taylor did not.

From July 1990 on INPFL took control of much of Monrovia.

On September 9, President Doe paid a visit to the barely established headquarters of ECOMOG in the Free Port of Monrovia. While he was at the ECOMOG headquarters, he was attacked by INPFL, taken to the INPFL's Caldwell base, tortured, and killed.

In November 1990, ECOWAS agreed with some principal Liberian players, but without Charles Taylor, on an Interim Government of National Unity (IGNU) under President Dr. Amos Sawyer. Sawyer established his authority over most of Monrovia, with the help of a paramilitary police force, the 'Black Berets', under Brownie Samukai, while the rest of the country was in the hands of the various warring factions.

In June 1991, former Liberian army fighters formed a rebel group, the United Liberation Movement of Liberia for Democracy (ULIMO). They entered western Liberia in September 1991 and gained territories from the NPFL.

In 1993, ECOWAS brokered a peace agreement in Cotonou, Benin. On September 22, 1993, the United Nations established the United Nations Observer Mission in Liberia (UNOMIL) to support ECOMOG in implementing the Cotonou agreement.

In March 1994, the Interim Government of Amos Sawyer was succeeded by a Council of State of six members headed by David D. Kpormakpor. Renewed armed hostilities broke out in 1994 and persisted. During the course of the year, ULIMO split into two militias: ULIMO-J, a Krahn faction led by Roosevelt Johnson1, and ULIMO-K, a Mandigo-based faction under Alhaji Kromah.2Faction leaders agreed to the Akosombo peace agreement in Ghana but with little consequence. In October 1994, the United Nations (UN) reduced its number of UNOMIL observers to about 90 because of the lack of will of combatants to honour peace agreements. In December 1994, the factions and parties signed the Accra agreement but fighting continued. In August 1995, the factions signed an agreement largely brokered by Ghanaian President Jerry Rawlings. Charles Taylor agreed. In September 1995, Kpormakpor’s Council of State was succeeded by one under the civilian Wilton G. S. Sankawulo and with the factional heads Charles Taylor, Alhaji Kromah, and George Boley in it.3In April 1996, followers of Taylor and Kromah assaulted the headquarters of Roosevelt Johnson in Monrovia, and the peace accord collapsed. In August 1996, a new ceasefire was reached in Abuja, Nigeria. Elections were planned to take place in 1997.

3. Liberia's Scheduled Elections: Guns Do Not Heal

In this article Tom Kamara casts his view at the upcoming presidential elections, which were held on July 19, 1997. He writes: “The scheduled elections will be between the men of guns on the one hand and civic society on the other. If Liberia is to put war behind and enter the millennium with a democratic and development agenda, then the choice is clear. The next leader must be a reconciler and a healer. Guns do not reconcile; they do not heal wounds.”

It seems that at last, Liberia is on its way to sanity after almost seven years of gruelling anarchy and plunder sustained by competing warlords. The protagonists of this senseless, mayhem, anarchy have resigned from the six-man state council to vie for the presidency. This means that after all, the principle reason for subjecting Liberians to the most heinous atrocities in the country's history since it was founded in 1822 was for these callous men of war and violence to become president.

The scheduled elections will be a test for all Liberians. All in all, it will be the first time that elections will be held in the country without an incumbent, and for a country that has a history of rigged elections. In the presidential election of 1927, the incumbent, President Charles D. B. King was re-elected with an officially announced majority 234,000 over his opponent, Thomas J. R. Faulkner of the People's Party. President King thus claimed a "majority" more than 151/2 times greater than the entire electorate. The scheduled May elections should provide a clean start. But will it?

Although, there have been successes in the disarmament process, there are fears that some warlords still harbor a hidden agenda and are concealing arms for a new offensive or destabilization scheme if they are justifiably punished for their crimes at the polls. For this, there must be a satisfactory level of de-commissioning of arms, free movement of people, repatriation of about one million Liberians who fled from the new presidential candidates, before elections. Otherwise, we may experience Sierra Leone, or Angola in this plundered country now slowly forgotten by the rest of the world.

Warlord Charles Taylor

Section C: The Johnson Sirleaf Era 2006-2012

On October 14, 2003, Gyude Bryant became chairman of the National Transitional Government of Liberia (NTGL). He was selected as chairman because he was seen as politically neutral and therefore acceptable to each of the warring factions, which included LURD, the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL), and loyalists of former President Taylor. He was a prominent member of the Episcopal Church of Liberia and was critical of the governments of Samuel Doe (1980–1990) and Taylor (1997–2003).1

Fighting initially continued in parts of the country, and tensions between the factions did not immediately vanish. But fighters were being disarmed; in June 2004, a program to reintegrate the fighters into society began; the economy recovered somewhat in 2004; by this year's end, the funds for the re-integration program proved inadequate; also by the end of 2004, more than 100,000 Liberian fighters had been disarmed, and the disarmament program was ended.

Considering the progress made, Bryant requested an end to the UN embargo on Liberian diamonds (since March 2001) and timber (since May 2003), but the Security Council postponed such a move until the peace was more secure. Because of a supposed ‘fundamentally broken system of governance that contributed to 23 years of conflict in Liberia’, and failures of the Transitional Government in curbing corruption, the Liberian government and the International Contact Group on Liberia signed on to the Governance and Economic Management Assistance Program (GEMAP), starting September 2005.2

The transitional government prepared for fair and peaceful democratic elections on October 11, 2005, with UNMIL troops safeguarding the peace. Twenty-two candidates stood for the presidential election. The 'big two' were George Weah (Congress for Democratic Change), world-famous footballer, UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador3and member of the Kru ethnic group, and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (Unity Party), a former World Bank economist and finance minister, Harvard-trained economist and of mixed Americo-Liberian and indigenous descent.

In the first round, no candidate took the required majority, George Weah won this round with 28.3% of the vote and Johnson Sirleaf 19.8%. Charles Brumskine (Liberty Party) took 13.9%.

A run-off between George Weahand Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, was necessary.

The second round of elections took place on November 8, 2005. Both the general election and runoff were marked by peace and order, with thousands of Liberians waiting patiently in the Liberian heat to cast their ballots.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf won this runoff decisively, winning 59% of the vote. However, George Weah alleged electoral fraud, despite international observers declaring the election to be free and fair. The Carter Center observed "minor irregularities" but no major problems. On December 22, 2005, Weah withdrew his protests. Johnson Sirleaf took office on January 16, 2006; becoming the first African woman to be elected as President after free elections.

30. The Mortality of Charles Taylor

March/April 2006

The Ajuba Peace Agreement had guaranteed Taylor safe exile in Nigeria. However, it also required that he refrained from influencing Liberian politics. His critics said he disregarded this prohibition.

On December 4, 2003, Interpol issued a red notice regarding Taylor, suggesting that countries had a duty to arrest him. Taylor was placed on Interpol's Most Wanted list, declaring him wanted for crimes against humanity and breaches of the 1949 Geneva Convention, and noting that he should be considered dangerous. Nigeria stated it would not submit to Interpol's demands, agreeing to deliver Taylor to Liberia only if the President of Liberia requested his return.

On March 17, 2006, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the newly elected President of Liberia, submitted an official request to Nigeria for Taylor's extradition. This request was granted on March 25, whereby Nigeria agreed to release Taylor to stand trial in the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL). Nigeria agreed only to release Taylor and not to extradite him, as no extradition treaty existed between the two countries. On March 27, after Nigeria announced its intent to transfer Taylor to Liberia, he disappeared from the seaside villa where he had been living in exile.

Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo was scheduled to meet with USA President George W. Bush in Washington less than 48 hours after Taylor was reported missing. Speculation ensued that Bush would refuse to meet with Obasanjo if Taylor was not apprehended. This condition was raised by Bush less than 12 hours prior to the scheduled meeting between the two heads of state.

On March 29, 2006, Taylor, 'the master of daring escapes' tried to cross the border into Cameroon through the border town of Gamboru in northeastern Nigeria. His Range Rover with Nigerian diplomatic plates was stopped by border guards, and Taylor's identity was eventually established. USA State Department staff later reported that significant amounts of cash and heroin were found in the vehicle.

Upon his arrival at Roberts International Airport in Liberia, Taylor was arrested and handcuffed by Irish UNMIL soldiers, who put him in a helicopter for Freetown (Sierra Leone). From there, he was transported to The Hague (the Netherlands) to stand trial in the Special Court for Sierra Leone. His trial began in June 2007.

In this article Tom Kamara, who wrote so many critical articles about Taylor, finally concludes “It is an end of brutal and primitive era that the dignity of people vanishes".

Is it an end of an era, an era in which men saw themselves as little gods on earth and therefore bequeathing unto themselves the power to give and take life? Perhaps not yet, because even as their tentacles are being clipped, fear of what they do, even in chains or death, spreads.

The names are many. Mengistu Haile Mariam4, Hisssène Habré 5, on the African side in recent time. Slobodan Milošević for Europe and the celebrated Saddam Hussein 6 for Asia or the Middle East. All fall in the same orbit of men who defied reality to proclaim themselves little gods on earth. The RUF, in their manifesto, referred to their leader Foday Sankoh as “The Zogoda”, perhaps a God-like or very powerful figure on earth.

“Jesus is angry. When God himself gets angry: hell would fall”, Taylor proclaimed in 1995 at one of his many press conferences against the media. The Jesus, he declared at the time, was Dr. George Boley, then his temporary ally. The God was himself. His estranged wife, Jewel Howard-Taylor, would reinforce her husband’s proclaimed deity. The only person greater than her husband, she told a journalist, was God.

Well, as this “god” stood under the pouring rain at the Roberts International Airport on Wednesday, he realized his mortality, his nothingness as a mere being. After all, he was just a frail person, one who took life so quickly fearing his would be taken.

Interesting. All those beating the hollow drums of maintaining his dignity, of Freetown unsuitability to judge him, and of protecting his human rights are doing only because it is politically correct to do, not that they believe is what is falling from their lips. Human rights organisations make their money championing the rights of the under dogs. In this case, Charles Taylor is the underdog, so attention is now swiftly removed from his many victims, or should one say alleged victims to be politically correct? And dignity? Does a prisoner have any dignity left? How can one who stands not accused by some street peddler down the road but by the international community, of rape, murder, mutilation, sex slavery, claim any dignity? To make matters worse, what can a man who runs away from justice, becoming a fugitive, claim any dignity? Adolf Hitler had some dignity in him, in that he never allowed his enemies to lay hands on him or his close associates. Saddam Hussein had none, for he soon dug a hole like a rat with the illusion he would never be found, all to save his miserable life even if he so quickly took the lives of others. Charles Taylor, the man who constantly portrayed himself as the embodiment of courage and bravery, took to his heels when the hour of judgment came. He always referred to others unprepared to use his methods as “rats and roaches”, since they ran to save themselves from his ever-multiplying executioners. Now, left without those means, he became a rat and a roach, for he ran like one of them.

It is so bizarre. This man, with the international stamp of notoriety engraved on him, still commands following, many of them silent followers because to defend him publicly is difficult for the normal mind to comprehend. There are many who benefited so immensely from his criminal exploits now secretly shedding their tears.

But his admirers and defenders are far fewer than those who see him as the man responsible for their state of being. There is another factor. In 1999 at a conference of West African leaders, Taylor actively campaigned for the immediate release of Foday Sankoh. He accused Sierra Leone President Ahmed Tejan Kabbah of being a stooge of colonialism and insisted that Sankoh, as a rebel leader, must be with his men if peace is to come. Kabbah’s response to Taylor was that he should be concerned with Liberian affairs and leave those of Sierra Leone to him. If he had only listened. He could not, so when some religious leaders from Sierra Leone, carrying the brunt of the war, came to Monrovia to beg for his mercy, he told them that the RUF was waging war to seize political power, just as he had successfully done in Liberia. If they wanted peace, he told them, they must prepare for power sharing with the rebels.

Now, as Taylor sits in that little cell in Freetown, completely sealed from the world outside, he must come to term with one undeniable fact: it is now a new era. Men like him, historical anomalies, will wither in the clouds of justice. All the predictions of apocalypse descending because justice has caught up with Charles Taylor will remain dreams in the shallow heads of his loyalists convinced that their days of economic plunder which he protected with the Small Boys Unit are gone. It is an end of brutal and primitive era that the dignity of people vanishes.

31. UN’s Trinity of Instability: Crime, Corruption & Violence

2008

In September 2003, the Security Council of the United Nations established UNMIL (United Nations Mission In Liberia) with up to 15,000 United Nations military personnel, including 250 military observers, 160 staff officers, and 1,115 civilian police officers. The main objective of UNMIL was to assist the Government of Liberia in the maintenance of law and order throughout Liberia.

According to the UN UNMIL would be able to contribute in a major way towards the resolution of conflict in Liberia, provided all parties concerned cooperate fully with the force and the international community provides the necessary resources.

The mandate has been extended annually until 2018.

In this article Tom Kamara analyzes the vulnerable situation in Liberia, while the UN Security Council extends on September 29, 2008 UNMIL’s mandate for another year.7

The scramble over meager resources in which competing national, along with their international partners are caught, is a prime cause of instability in Liberia, the UN Security Council, in its recent resolution extending its mission’s mandate for another year, has observed.

The Council, in pointing out the three evils, said it recognizes “the significant challenges that remain in the consolidation of Liberia’s post-conflict transition, including consolidation of State authority, massive development and reconstruction needs, the reform of the judiciary, extension of the rule of law throughout the country, and the further development of the Liberian security forces and security architecture, in particular the Liberian National Police, and noting that crimes of corruption and violence, in particular with regard to exploitation of Liberia’s natural resources, threaten to undermine progress towards those ends…”

On the other hand, the former chair of the National Patriotic Party, the parent group of the ex-rebel outfit the National Patriotic Front of Liberia, Cyril Allen, has attributed the horrifying crimes the NPFL rebels committed and the attending instability to “the zealousness of the Liberian people”. If this explanation is accepted in its simplistic form, then it implies that all born within the territorial confines of this land mass are zealous by nature and must, due to this innate and inescapable zealousness, commit crime.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf: fLTR: as a young opposition activist after her release from prison following Quiwonkpa's failed coup attempt in 1985; amidst women in Ghana during the peace talks in 2003; as President of Liberia (2006-2018).

To the contrary, there is the contention that corruption leads to underdevelopment and therefore instability, as the UN Security Council observes. Decades of neglect of the rural youths, the cannon fodder of the rebellion, sowed the seeds of instability to significant levels, because there is a co-relation between the knack for violence and lawlessness and the lack of education and opportunities. Ghettos and townships register more crimes and violence than middle class areas. And when individuals, with a political agenda tied to crude wealth accommodation, recruit the peasant youths with drugs as the stimulus, zealousness is hardly the answer for the avalanche of horrors and instability. Lack of opportunities and education made them more vulnerable to manipulation as agents of instability, not zealousness by birth.

President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf has reached similar conclusions as the Security Council, which is that corruption leads to instability because it undermines economic progress with threats to instability. In a speech before her new army of anti-corruption warriors, she underlined the difficulties and challenges, admitting that when she declared the plague her enemy number one, she underestimated the powers of the enemy. She declared:

"When we took office in January 2006, we knew that corruption was a serious malaise. We vowed then to make corruption public enemy No. One, not realizing the extent of its roots, systemically, and culturally. Twenty years of dependency deprivation and lawlessness have indeed taken its toll.

Corruption and poverty are deeply intertwined. Corruption is a major obstacle to sustained economic growth, poverty reduction, and social development. It distorts the rule of law, weakens the social fabric of society, and undermines the institutional foundation on which economic growth depends.

At the same time, underdevelopment itself makes fighting corruption all the more difficult. Poverty makes corruption more of a temptation for underpaid officials, and weakens a society’s ability to build the institutions, the checks, and balances necessary to combat corruption. This is not to say that poverty is a problem only in poor countries, as is sometime supposed. Newspaper headlines make it abundantly clear that even in the richest countries of the world, corruption remains a problem. But there is no doubt that poverty and corruption feed off of each other, and this negative reinforcing cycle makes the fight against poverty both more difficult and all the more important at the same time…."

The key words in the President’s remarkable speech, remarkable because of its frankness in admitting the invincibility of the enemy, are poverty. More than a century back, some philosophers reached the same conclusions as the president. It was the German, Karl Marx, who decreed that poor people cannot change society because they are preoccupied with the search for bread to think. In Liberia, as other parts of Africa, the diagnosis holds true. Most of the countries at the bottom of scale in Transparency International ’s anti-corruption measurement are African countries. Liberia, jumping from place 23 to place 42, celebrated, but the concern is the conditions applied in ranking countries. Of course, Liberia had to jump, because contrary to the past, the President is unlikely to stack the country’s dollars under her bed, as Charles Taylor and other presidents have been accused of doing.

But President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, in diagnosing the enemy, also listed her ammunitions she said she has used, prime amongst them dismissals where she evidence is adduced. She declared:

“We have dismissed several Government officials for which there was evidence of their violation of the Public Trust. Some fifty cases, involving violation of varying degrees have been forwarded to the Ministry of Justice by the National Security Agency…”

If poverty is an obstacle to fighting corruption, and with the fact that all Africans are basically poor, does dismissals solve the problem? Realistically it does not, because regardless of who is appointed, the agenda is clear. `It is a matter of what is in it for me’. All in all, the beautiful ones cannot be born in poverty. Poverty makes everyone ugly. This makes the President’s time limit for the spreading corruption—over the past 20 years—unfair. The plague germinated with the birth of the Liberian state, and since the demand for scarce resources has intensified as a result of rising population and the changing socio-economic and political landscape. The scramble has taken violent dimensions with the destruction of those economic institutions that should have addressed poverty. Stability is repeatedly threatened by intractable poverty invincible due to unstoppable corruption.