Table of Contents

Praise

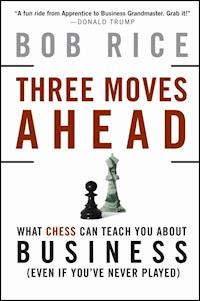

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

PREFACE

CHAPTER ONE - THE WALL STREET CHESS CLUB

CHAPTER TWO - THREE MOVES AHEAD?

CHAPTER THREE - FIRST MOVER

FIRST—MOVER ADVANTAGE

A CLASSIC FIRST MOVER

WHAT’S THE BIG IDEA?

THE CHESS GUIDE TO BUSINESS PLANS

OPENING PRINCIPLES

AN ENTREPRENEURIAL REPERTOIRE

CHAPTER FOUR - ON THE CLOCK

STAY AHEAD ON THE CLOCK

BUSINESS TIME

DISCIPLINED URGENCY: FINDING A RHYTHM

LEAVING YOUR FINGER ON IT

THERE’S ONLY ONE PRIORITY ZERO

THE PLAYER DECIDES

PLAYING TOO FAST

THE EXECUTIVE’S CLOCK

A CHESS TRAGEDY

CHAPTER FIVE - BAD BISHOPS

THE EXECUTIVE TEAM

BISHOPS AND KNIGHTS

DON’T GET OVERLOADED

PREVENT PINS

THE KNOWLEDGE WORKERS

CHAPTER SIX - LUCKY OR GOOD?

THE NATURE OF PLANS

EMERGENT OR DIRECTED? POSITIONAL OR TACTICAL?

THE PLANNING PROCESS

THE SECRET: IDENTIFY THE IMBALANCES . . .

. . . AND THEN FIND A DREAM POSITION

BREAKING OUT OF THE BOX

BACK FROM DREAMLAND: FROM THERE TO HERE

A BAD PLAN IS BETTER THAN NO PLAN

CHAPTER SEVEN - STRONG SQUARES

SQUARES AND PIECES

JUST ONE?

WHAT IS A BUSINESS STRONG SQUARE?

NEW SQUARES ON THE BOARD

IDENTIFYING YOUR STRONG SQUARE

THE GREATEST PLAYER IN HISTORY?

CHAPTER EIGHT - SAC THE EXCHANGE!

THE TRICK IS KNOWING WHEN

HOW IT WORKS

A FEW NICE MOVES . . .

HOW WILL THE NETWORK EXECS PLAY IT?

CHAPTER NINE - CLASSIC TACTICS

PRINCIPLES OF ATTACK

PRINCIPLES OF DEFENSE

RESPOND TO WING ATTACKS WITH ONE IN THE CENTER

PROPHYLAXIS

CHAPTER TEN - DECISIONS, DECISIONS

FIRST, WHAT HAS CHANGED?

SECOND, WHAT’S THAT PLAN AGAIN?

THIRD, WHAT ARE OUR CANDIDATE MOVES?

FOURTH, FILTER

NOW, CHECK YOUR ANSWER!

A POSTGAME RECAP

NOTES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

INDEX

“A fun ride from Apprentice to Business Grandmaster. Grab it!”

—Donald Trump

“Three moves ahead? I’d say four, at least. An utterly fresh guide to winning in today’s business environment.”

—Jim Spanfeller, CEO, Forbes.com

“Every executive struggles with the pressure to think fast and think ahead. Bob’s fascinating book shows how to apply chess principles to do just that. It’s impossible to make the right move every time, but these strategies will help you succeed in the face of the unpredictable.”

—Bruce Chizen, former CEO, Adobe Systems Incorporated

“This amazing book is the first time anyone has clearly translated Grandmaster ideas to real-world situations. The business examples are so good that I’m using them to teach chess!”

—Maurice Ashley, International Chess

“Rarely does one find a book where every page is filled with both brilliant insight and witty writing. Mandatory reading for every startup.”

—David S. Rose, founder, New York Angels

“I don’t play chess but it sure improved my ‘game’ at the office! The clever, clear examples show how to use dozens of classic strategies in everyday situations. This book can put any executive ‘three moves ahead’!”

—Sarah Fay, CEO, Carat USA

Copyright © 2008 by Bob Rice. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741—www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Jossey-Bass also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rice, Robert, 1954-

Three moves ahead : what chess can teach you about business (even if you’ve never played) / Robert Rice.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-17821-8 (cloth)

1. Strategic planning. 2. Success in business. 3. Decision making. 4. Chess—Psychological aspects. I. Title.

HD30.28.R498 2008

658.4’012—dc22 2007050894

HB Printing

To Lenore, my best move, and our two great wins,Eric and Isabelle

PREFACE

As it turns out, information age business comes with a 1,000-year-old user’s guide.

That’s fortunate, for our suddenly flat world is inflicting business disruptions of historic proportions. It has obliterated many of the traditional barriers to entry: physical plant, local suppliers, and guarded relationships. It has amped up the volume of information to deafening levels. It has introduced new competitors from places we didn’t even know existed. It has compressed the time for making decisions and shortened every sort of business cycle, from product launches to stock turnover time to CEO life spans. Intellectual property, not physical property, has become the weapon of choice.

This wave has overwhelmed standard business analytical tools. Nearly all of these involve some variation of reducing possible choices to their present economic values, with the one that generates the biggest number winning. Problem is, doing that requires the business equivalent of a giant sloth: the kind of slow-moving, predictable market that is now nearly extinct. To a radically greater degree than ever before, today’s strategic and operational decisions must be made without a clear understanding of their outcomes. That is, to compete successfully in the “information revolution,” you have to know what to do when you’re not sure what to do. Chess teaches that. And that’s why the greatest strategy and knowledge game in human history is so relevant to today’s business issues.

In the following pages, you’ll see how great companies in every industry, from Adobe to 3M, and from start-ups to conglomerates, use these strategies to compete effectively in our wildly unpredictable world. Many of them are proven offensive and defensive principles for attacking and defending markets, some demonstrate how to get new ventures off the ground, while others illustrate how to maximize and revitalize a withering advantage. Several relate to building efficient organizations, a handful show how to maintain momentum while under attack, and still others help you choose among reasonable alternatives while under pressure.

All have proved effective over centuries of competition by brilliant minds, so you can be pretty confident that they’re correct. Should you doubt that, just look at how profoundly the game has always reflected and informed the major aspects of society.

The “DaVinci Code” of the late middle ages, the blowout blockbuster of the pre-movable type days, was Book of the Customs of Men and the Duties of Nobles. The killer title alone didn’t account for its success. 1 Written by an Italian monk, it tells the story of a king so wicked that he hacked his father into 300 pieces and fed him to the vultures. Fortunately, in the big plot twist, he then learned the game of chess. That redeemed him, for the formerly evil one came to understand that his position was utterly dependent on the society functioning as a whole and the performance of its lowliest members.

The author portrayed the individual pawns as blacksmiths, innkeepers, messengers, and the like, and the more important Knights, Bishops, Castles, and Queens played themselves. This medieval morality play proved so popular over such a long period that it was translated from Latin into French, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, Swedish, English, and German and even earned 20 editions after the printing press was invented 150 years later.

Indeed, the game has always served as a mirror of intellectual and societal evolution and often as a precursor of important developments. Before Customs of Men, for example, it had been a religious lesson. The pieces came out of the same bag, sprang to life for a while during the game, and then all went back into the same bag together. Regardless of your worldly situation, a return to God, from whence you came, leveled the experience.

Later, chess prophesized political developments. Perhaps its most prescient moment came in the late 1700s, when the great French player Philador observed that “Pawns are the soul of chess.” That was as revolutionary a thought for chess theory, sparking a profound reevaluation of proper play, as it was about to be in French politics. If Marie Antoinette had just checked out the Café Regence, trendy hotspot of the chess world, she might well have been a little less cavalier in her unfortunate suggestions about dietary substitutions.

Even social moods and customs have been played out on the board. The swashbuckling, territory-conquering 1800s gave rise to the “romantic period” in chess, during which no self-respecting, man’s man would fail to offer a risky gambit or to accept one. Next came the Classical period, which rejected these “unsound” romantic ideas in favor of a model featuring rigorous rules about the “proper” way to play, which very much echoed the staid mores of Victorian England.

Then came a surprising pas de deux between science and chess. At the end of the nineteenth century, scientists were concluding that Newtonian physics had essentially answered all the big questions and that the discipline had no future. At the same time, Grandmasters lamented that all the secrets of the chessboard had been found: World champion Emanuel Lasker complained that the game had been studied so much that all the correct moves were understood.

And then earthquakes hit both disciplines. Albert Einstein’s “miracle year” of 1905 upended Newtonian classicism with his theory of relativity and the idea of the “quantum” (later spawning the uncertainty principle, a concept relevant to this book). The chess echo came from the “Hypermodernists” of the 1920s. Steinitz, the chess world’s Newton, had long before set down the “universal law” that early occupation of the center of the board was the key to winning chess games. But the Hypermodernists dared their opponents to do just that while they sat back and attacked from the wings and corners. This shocking challenge to orthodoxy proved just as influential to chess theory as relativity would to physics.

At the same time, similar revolutions arose against classicism in art, theater, and government. One of those, the Russian Revolution, intensified the interplay between human events and the (formerly) “royal game” when the Soviets seized the game as a symbol of communist superiority.

The Soviet School successfully produced a tide of dreary, oppressive technocrats who dominated world play for decades. The style was built on the excruciatingly slow buildup of pressure, incrementally overpowering opponents while taking no risks. Then, once again playing political pundit, the game signaled the beginning of the end of the Cold War when Bobby Fischer unseated Boris Spassky as champ in 1972, an event second only to the “Miracle on Ice” for sporting ignominy in Russia. Although the old Soviets were able to regain control of the game briefly when Fischer abdicated his throne (believing, among other things, that Martians were sending radio signals to the filings in his teeth), the coup de grace was ultimately delivered from within by Garry Kasparov, an Azerbaijani Jew who was the antithesis of the regime personally, politically, and stylistically.

Even though Kasparov was indisputably the greatest player in history, his outsider status generated overwhelming state resistance. The KGB spied on his match preparations to better equip his opponents, and the Russian government conspired with the world chess authorities to cancel a world championship match just as he was about to pull off the greatest comeback in sports history. He overcame these obstacles to become the ultimate anti-Soviet champion and fittingly reigned over the chess world as the old order collapsed. His current political activism is just a continuation of his brave career.

Chess has thus always mirrored, and even predicted, civilization’s dominant themes. Especially given the fundamental role that business has assumed in the world’s social order, it would be shocking, indeed, if the game failed to provide important lessons for modern executives.

So, let’s see what this “user’s guide” has to say.

CHAPTER ONE

THE WALL STREET CHESS CLUB

A couple of years before quite accidentally becoming its CEO, I ran business development for a small public company. It was the 1990s, we had some cool graphics software, and I was headed to Redmond to sell it to Microsoft . . . or so I thought.

After years of work and interminable reviews by their technical experts, we believed our moment of glory had finally arrived. We expected that soon we’d announce a huge transaction with the industry leader, rake in a fortune, and watch our stock rocket.

But then the meeting actually started. My Microsoft counterpart opened the proceedings by reading me what he called, with absolutely no sign of a smile, the “rules of engagement” for dealing with his company. Turns out, these were essentially a corporate version of the Miranda rights, the ones police have to read when they arrest you. (Actually, that was only fair: Bill Gates is a lot scarier to a small technology company than the local sheriff.)

Instead of the right to remain silent, you had the right to not do business with them at all; it was, mercifully, still possible to just leave. If, however, you did decide to proceed, two things were absolute: one, Microsoft would own your software lock, stock, and barrel; and two, you would be paid absolutely nothing for it.

Hmm. Well, this was not exactly the sort of shrewd deal that I expected to win me a bonus. In fact, it didn’t: I almost got fired for accepting.

Whatever possessed me to say yes? My chess gut said it was time for an “exchange sacrifice.” Now, for some reason, that particular explanation didn’t completely mollify the unruly crowd back at the office. Even the famously practiced L.A. cool of our black-tee-and-shades CEO got blown, reportedly causing him to bang up his IPO Porsche when he got the news via cell phone. So, forced to defend this “little brilliancy” to the entire board of directors, I tried a different approach.

Look, hard as it was to swallow, what Microsoft was saying was true: that we could only become a major company if our software reached enough people to make a difference, and that could only happen through them. Well, correct, we could not continue licensing our desktop software to companies once it was free as part of Windows, so, yes, we would have to find an entirely new business model . . . and, no, we hadn’t quite worked that one out yet. To the board, unfortunately, I was unable to repeat the Microsoft guy’s detailed analysis on this point: if, with this new Internet thing happening, we weren’t smart enough to find a way to monetize the fact that our software would be on tens of millions of machines, he reasoned, “You suck.”

So it boiled down to two options. We could continue to license our code for a few dollars here and there and risk slowly becoming passé, or we could get it into use by many millions of users quickly (albeit for free) and find some new way to play in the next, Internet phase of the game. Even though we couldn’t exactly see how to exploit the distribution, and even though it meant junking the model that had paid the rent, we had to go for it—what chess players would call an exchange sacrifice—trading one kind of advantage for a completely different sort, even though the exact benefits can’t be calculated.

And, fortunately, the plan more or less worked. We did get our software onto more than half of all computers in the U.S., and we did figure out a new business model based on that fact, although in the short run, it didn’t generate enough revenue to replace what we gave up. Instead, as is the idea with this kind of move, the real payoff came later: The new model propelled us directly into what would become the white-hot Internet advertising business, in a way that the old one never could have. Meantime, nearly all the graphics companies that stuck to their old desktop business models died on the vine as the Web blossomed.

Brilliant long-term planning? Hardly. But it wasn’t pure luck, either. We did figure that this “Internet thing” just might be a hit, but we had no more idea than anyone else how Web advertising would evolve. Nonetheless, we wound up ideally positioned for it. We didn’t have a crystal ball, but we were playing chess.

It’s often that way: the best business moves come right off the board. Indeed, what’s amazing is how many chess principles are directly applicable to the world of business and how they can help executives make the right move in so many situations—with strategic development, of course, but also when attacking competitors, defending turf, cracking new markets, and, well, in just about every aspect of running a business these days.

The idea for this book began to dawn on me long before my stint as the biz dev guy (and later, CEO) of that software company, back when I was still a lawyer, while scanning the audience at a world championship match between Garry Kasparov and Anatoly Karpov in New York’s Macklowe Hotel in 1992. The room was absolutely teeming with famous Wall Street guys, some I knew from my practice down there, some were stars I’d never met: George Soros, Steve Friedman (head of Goldman, Sachs), and Jimmy Cayne, who ran Bear, Stearns. Was that an accident or a clue?

That question sparked the creation of the Wall Street Chess Club. And what a club it became. On our very first night, we got the above luminaries as well as a virtual “who’s who” from all the other Wall Street shops. Word spread through the chess circles of New York’s large Russian émigré community, which had recently been supplemented by a huge influx of top Grandmasters (GMs) who bailed out as things got shaky in the old Soviet Union. Soon we were nearly overrun by top players. I guess their usual clubs didn’t offer fine red wines and gourmet sandwiches or feature expansive views over the Statue of Liberty in the harbor far below. But for whatever reason, we suddenly had the strongest club in the world.

Among the regulars and guests were ex-world champions Tal, Spassky, and Karpov; other “super GMs” like Dzindzichashvili (later my teacher), Albert, and Kamsky; the American stars Ashley, Rhode, Benjamen, Seriwan, and Wolff; the rage of the chess world, the three Hungarian Polgar sisters; and eventually, the greatest player ever and reigning world champion, Kasparov himself.

The running joke was that the executives were coming to learn to play chess, and the chess players were coming to learn to make money. But the communities blended very well indeed, and many players ultimately took jobs at the investment houses, often as traders; Banker’s Trust actually launched a formal recruiting effort to bring in GMs.

So the question was answered. Chess and business did indeed share a deep connection.

Soon thereafter, Kasparov asked me to help him start the Professional Chess Association, a rival to the then-worldwide governing body of chess. We staged all sorts of events in unusual venues with unique formats, including the first commercial event ever held inside the Kremlin (during which our sponsor got more than its money’s worth when a well-placed gratuity got the “Intel Inside” logo projected on the outside walls for a night, an image that was flashed all over the globe); a world championship played atop the World Trade Center; and a “speed chess” TV series hosted by Maurice Ashley for ESPN.

But the life-changing event occurred later, when Kasparov introduced me to a brilliant Russian physicist, Sasha Migdal, a Princeton professor who had invented a three-dimensional camera (I’ll explain later). Blinded by the possibilities, I quit the practice of law and jumped into a true start-up. That’s when I got my chance to put chess theory into business practice.

Fortunately, I didn’t know a thing about the basic rules of business at the time. If I had, I’d still be a lawyer because one of those rules probably says to make sure you have a viable product before you leave a cushy job and bet the farm on it. Much to my dismay, it turned out that there was actually no demand at all for what we were selling—and just about the only good news about that was that it didn’t turn out to matter much, as the product didn’t actually work so terribly well, anyway.

But, because we “played chess,” things turned out OK. We went into a “deep think” about our position after an embarrassing series of setbacks (including, in a heavily promoted stunt, posting 3D pictures of all the Miss Universe contestants on the NBC Web site the night of the show. Our expected tour de force turned into a disaster because the then-nonstandard systems for displaying 3D on the Web rendered these gorgeous women as mangled Picassos on everybody’s computers except ours, and we were almost sued by Miss Argentina). We decided to play our first “exchange sac” by jettisoning the camera and relying on the underlying algorithms to develop graphics software for the Internet. We then pursued a “first-mover advantage,” “castled early,” established a “strong square” in Web 3D, and got bought by a public company.

Of which I became CEO at the exact moment that the fantastic Internet bubble burst, taking our stock price and most of our customers with it. Our game hung by a thread. But we went on, one move at a time, not knowing what the endgame would be. We just kept making the next best move we could find, accumulating small advantages and trading them for others, until suddenly the winning path, Internet advertising, emerged.

The more or less happy result ensued largely because I had one piece of training most MBAs don’t: my sister Dianne had taught me to play chess as a kid, and the Bobby Fischer match made it stick.

But, as you’ve seen, that didn’t equip me to predict the future. Despite what most nonplayers believe, winning at chess is not based on the skill of seeing ahead 15 moves (or, as we’ll see, even three).

Nor, fortunately, is it about IQ, another common misconception. We might as well pop that bubble right now: most great chess players are of average intelligence. Sure, some people are naturally more talented at the game than others, just as some folks learn to play the piano or speak a foreign language faster than most, but none of these mental skills means beans about how “smart” you are in the typical sense of the word. Anyone can become competent at chess, just as they can at music or language, simply by learning and practicing the basic principles.

No, far from being a dry science of pure calculation and certain foresight, world class chess is about having a plan to generate an advantage but prosecuting it in a flexible way; at the right moment, swapping that advantage for one of a different sort, and then doing it again; moving quickly even when you’re not exactly sure what to do; making intelligent sacrifices; taking risks; believing in yourself; and dealing with the present, not the past.

That said, there are, of course, several concrete strategies and tactics to understand; that’s what the book is about. These methods do not banish uncertainty, but they do position you to take advantage of it. They set you up for “unexpected” success.

After all, these strategies and tactics guided an outsider, a country-bumpkin lawyer like me (who, when introduced to Leon Black not only asked what he did for a living but followed up with “And what’s an investment banker?”), into position to become a partner at one of the most prestigious law firm on Wall Street, which led to the Wall Street Chess Club, which in turn led to my running that event in the Kremlin. This then gave me the chance to launch a start-up with the guy who solved two-dimensional quantum gravity theory (and whose father created the Russian hydrogen bomb), which then, despite the Miss Universe fiasco, got acquired by a screenwriter’s exaggerated version of a wacky West Coast public company. My annointment as CEO of that company happened mostly because the board figured I’d play better in an accidentally scheduled “Power Lunch” interview than my seriously surfer dude predecessor.

So, you can see, my career path wasn’t exactly a 15-moves-ahead type deal. Instead, it happened precisely because I didn’t have a long-term fixed plan to disrupt. The basic principles of good play—get a big idea, use it to build an advantage, improve it, swap it out for a new one, move quickly, see what happens, make a new plan, and move again—worked on a professional level just as much as they do in corporate warfare.

Indeed, the more you look at the business world, the more you see that successful companies and the people who run them use chess strategies routinely (whether they know it or not): to create strategy, manage people, make decisions, and most of all, cope with the rapidly increasing rate of change in the world, with the unknowable future.

CHAPTER TWO

THREE MOVES AHEAD?

I bet you’ve heard a friend say, “I like chess, but I’m not very good at it because I can only see two or three moves ahead.” Probably you didn’t think much about it at the time, but what’s your apparently modest buddy actually saying here?

Well, in an average chess position, there are about 40 possible moves, so seeing one full move ahead (yours and your opponent’s response) would involve 1,600 positions (40 × 40). If we take that to the breathtaking number of two moves out, your friend is claiming that he’s seeing over 2.5 million positions. Three moves? Four billion. The guy’s totally full of himself! How do you put up with him?

Just one more minute on the math. Because an average game lasts 40 moves, one can fairly easily calculate the number of unique games to be on the order of 10128. That is hugely larger than the number of known atoms in the universe, which, as Fred Friedel, the godfather of the world’s chess community, points out, is a “pitiful” 1080.

We won’t dwell on the amazing fact that humans can still beat supercomputers at such a game, or how their techniques for doing so can help you manage a business amid the even more incalculable uncertainties of the information revolution. That’s what most of this book is about, so we have time. However, what is essential, right up front, is to chew on the question of what it means to “see ahead,” in chess and in business.

First, perhaps you think the number-waving above is overly dramatic; some of those possible moves, after all, would be inherently foolish. Sure, but ponder this: A substantial percentage of the smartest people of the past few hundred years have collectively played billions of games, and yet, there is still no consensus about the best way to even start the battle. I remember one game in the 1990 world championship in which Garry Kasparov absolutely shocked Anatoly Karpov, along with the 1,000 spectators in the hall, by opening a game with the Scotch, a system known since 1750 but that had not been played in a world championship match in more than a century. Karpov, himself among the handful of best players ever, was stunned by a line of play a quarter-millennium old. The point was not merely surprise: On a deep review of the opening, Kasparov had discovered some new ideas he wanted to try out. Even such an ancient system, picked over for hundreds of years by the best players, could produce brand new possibilities.

Indeed, the apparently precisely knowable world of chess is so unknowable in practice that ideas about the “right” way to play have ebbed and flowed over the years in parallel with other ongoing human battles with the unknown: art, politics, theater, and military science.

What does all this mean for us? One point is this: Despite the fundamentally limited options presented by an eight-by-eight squares board with just six different kinds of pieces and hundreds of years of thought by our smartest folks, there is not a single best way to play. Ideas and styles change. There are no sure-fire recipes for success.

But, chess has refined a set of principles over hundreds of years that show how to conduct an organizational battle in a hyperdynamic environment, where the future is unknowable (three moves is four billion positions) and the situation changes with every move—a challenge, one might say, very much like that faced by executives caught in the roiling uncertainties of today’s information revolution.

After all, if we can’t accurately forecast the course of a simple chess game, so narrow in comparison to real life, how can we do so for something as complex as a business in this environment? We can’t. Or at least we can’t in the way that people have usually thought about planning a business, with detailed long-term budgets and clear views about the future competitive landscape. That may have worked for Ma Bell in the fifties, but as its collapse demonstrated, such thinking simply cannot work in today’s world. Instead, we need to grapple with the uncertainties, to “play business” like Grandmasters.

Fine, fine, fine, but does chess really have anything concrete to offer executives? Aside from bromides like “think ahead” and “move with a purpose,” what does it bring to the party? To answer that, let’s see who’s already arrived at our little business advice get-together.

A trip down the business aisle at Borders will yield a book that preaches maniacal discipline . . . right next to one insisting on lightning agility. There’s a manual of execution alongside a gospel of innovation. Here’s one demanding a laser focus on core competencies, while its neighbor beseeches the development of breakthrough products. Some call for aggressive leadership; others dictate a quiet, collaborative style. Some demand breakneck speed, and some advise gradual change. Apparently each of these deeply contradictory formulas is the key to success.

On first reading, many of these tomes seem persuasive. But mostly they share a fundamentally flawed methodology. The usual formula is this: find several companies that have done well; identify a few characteristics they have in common; and conclude that if readers do these things, too, they’ll find similar success. Although the best of this genre, such as Tom Peter’s In Search of Excellence and Jim Collins’s Built to Last, do offer worthy insights and ideas, they suffer from the same profound logical flaw. And it is this: Thousands of companies that also shared the touted characteristics were complete failures. Moreover, a review of the companies featured in such books a few years after publication speaks even louder about the “rules” they were following: would you really like your company to be like Digital Equipment, Wang, Polaroid, or K-Mart?

Aside from the basically flawed methodology, the problem with many such books is that they ignore the wildly variable contexts in which businesses find themselves. For many companies, trying to apply the lessons of such books would be like a new motorcycle owner reading instructions for riding a bicycle—vaguely similar, yes, but good luck when you try to brake by backpedaling. What behavior, for example, can be learned by studying the success of YouTube? Certainly, one would conclude by the financial success of the founders that it must have done a lot of things right. But if you followed those steps exactly today, with the same kind of management philosophy, you’d get creamed; the circumstances leading to its success were simply too unusual. The truth is that an idea that’s worked once, or even several times, may well have zero precedential value for subsequent businesses.

Finally, readers of recipe-for-success books often fail to produce a nice cake for a simple reason. In the kitchen, there are rarely opponents who fight you tooth and nail for access to the springform pan. Most business advice books do not account for this fact. Instead, they preach that internal factors are primarily responsible for an entity’s success. But in real life, someone’s over there playing the Black pieces, and she gets just as many moves as you do.

Of course, a company’s internal health is certainly a factor. But lots of companies with great quality control, focus, and customer-centric cultures fail because of events outside their control: the market, competitors, new technologies, changed government regulations, and a long list of other reasons. Regardless of how many companies with good internal dynamics do become successful, such factors are only one ingredient of success. How you play the ever-changing external world is certainly as important.

And the stocking of those bookstore aisles is finally beginning to reflect this. The best-seller list is shifting from tomes of sure-footed advice, guaranteed to work in every situation, to ruminations on the rate of change, the level of unpredictability, and the impact of happenstance: The World Is Flat, The Tipping Point, The Innovator’s Dilemma, The Black Swan, and The Halo Effect.1,2,3,4-5

So the trip to the bookstore didn’t work out. Maybe we should have gone to business school instead? Alas, a quick tour of the history of corporate strategy as taught in the leading business schools is a little like being back in Borders.

It’s probably fair to say that the three essential aspects of any business are, one, what market it is fighting for; two, how the entity is organized and equipped to conduct the battle for that market; and three, how it deals with competitors, change, and the intrusion of the unexpected. And these, in turn, were the dominant topics of MBA training over the past 30 years. The first point, “What industry should you be in?” was the central theme of the early eighties. Because certain markets are inherently more profitable than others, the thinking went, please direct your attention there.

The second push revolved around “competing on capabilities.” At this point, the focus moved from an industry-level focus to a company-centric one; it became fashionable to identify “core competencies” and to become a “learning organization.” The shift became so pronounced that one could assume success would follow naturally from any well-run company, regardless of the industry it was in or who its competitors were. As noted above, this aspect of corporate strategic thinking is still heavily represented in the popular press.

Predictably, the pendulum then swung back. In the third wave, the catchphrase became “competing on resources,” which essentially combined the first two big ideas: Success really depended on applying capabilities to the markets and competitors (the “environmental factors”) it was trying to attack.

Meantime, from outside the lines came some basic questions about how corporate strategy should—or even could—be developed. “Logical incrementalism” challenged the basic idea that companies could systematically develop and implement strategies at all (and despite its proponents’ protestations that they were not prescribing willful muddling, they were prescribing willful muddling). A close cousin was the “emergent strategy” school, which proposed that good ideas would emerge from the muddling and that those should be followed.

Then the mathematicians got into the game and noted that strategies had to build off game theory: Competitors will take account of each other’s likely actions, and reactions to actions, in calculating their own. The timing was good for this idea because game theory generally assumes that perfect information is available to the players; secrets spoil the game. The Internet, of course, has come along to provide just the sort of pricing and resource transparency that Nash equilibrium theories require. But even game theory assumes that players can fully evaluate the relevant data and make predictions about the future. It doesn’t explain what to do when both sides have too much information and too little time to evaluate it, which are precisely the conditions of chess and today’s business world.

People management is usually considered a separate topic from strategy. Of course, it isn’t: Plans cannot succeed without the right people to implement them, learning organizations won’t learn if they don’t have any students inside, and emergent strategies won’t emerge if the right folks aren’t detecting and fostering them. All organizations are composed of people of different abilities and motives, and despite what the HR folks say, the way people act does not change much regardless of what job title you bestow, how much training you provide, or what the job description says. So yet another important element of success is the art of “strategic people management”: creating structures for these relatively inflexible “pieces” to best perform the desired tasks.

I guess you can see where this is headed.

The argument of this book is that chess is a physical manifestation of just about all the ideas that the authors and academics have been arguing about. It is, in fact, a centuries-old test bed for these key concepts, its players lab rats trying out the best strategies for conducting a competition of organizations composed of pieces with different skill sets and values in a rapidly changing environment.

To test the proposition, let’s revisit those three big waves of strategy studies. Certainly any good player is skilled at choosing what squares (markets or industries) he is setting forth to control, just as executives were taught to seek out the most profitable ones. Players are equally expert in knowing how to coordinate the actions of their different pieces, to create efficient and well-run organizations: to “compete on capabilities.” Finally, they have developed highly refined techniques for using those strengths against particular weak spots in the opponent’s position: to “compete on resources.”

Players’ strategies do emerge over time; they are the very subjects of game theory, and their plans are based on “strategic HR.”

Finally, as befits the information age business, a Grandmaster is under immense time pressure that requires decisions to be made “too quickly.” He understands very well that he cannot see the future clearly but that he must nonetheless make decisions and chart a plan anyway.

Of course, chess is not a perfect representation of the business world. First and most important, it permits only one winner and assumes only one opponent. Second, it provides equal starting resources, an orderly taking of turns, and that both players agree on and follow the same set of rules. Third, as noted, there are no lies and no secrets in the chess world. Finally, but very importantly from this book’s point of view, it is far, far simpler than the business world.

For as mammothly complex as chess is, as unimaginable as all the possibilities are, it is still a game played with just six different kinds of pieces on a board measuring eight squares by eight squares. How does that compare with the complexity of life? How does having a single opponent, playing under strict rule, with equal resources and clear time limitations, compare with the jungle of modern-day business competition?