Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

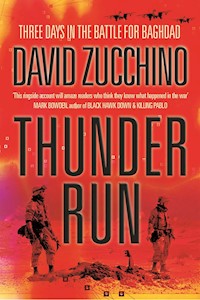

Thunder Run is the story of how, with fewer than a thousand men, and facing dug-in Iraqi forces, the Second ('Tusker') Brigade of the Third Infantry Division punched a hole through the heart of Baghdad with a high-speed charge to Saddam Hussein's Presidential Palace and Republican Guard headquarters. The product of dozens of interviews with commanders and men from the Second Brigade, it is more than just a book about a single battle. It is a riveting account of how soldiers respond under fire and and how human frailties are magnified in a war zone. Many people believe that Baghdad was taken with a minimum of effort. But for the Tusker Brigade it was a cruel and terrifying three days of urban warfare. Thunder Run tells the inside story of one of the most brutal and decisive battles in combat history and the biggest armoured battle involving American troops since the Vietnam War. It is an unputdownable, unforgettable first-hand account of how a single armoured brigade of fewer than a thousand men captured an Arab capital defended by one of the world's largest armies.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 702

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THUNDERRUN

David Zucchino is a foreign correspondentfor the Los Angeles Times.His work has been short-listed for the Pulitzer Prizeon three occasions.

First published in the United States of America in 2004 by Grove/Atlantic, Inc.,841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003–4793, USA.

First published in paperback in Great Britain in 2004by Atlantic Books an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This E-book edition published by Atlantic Books in 2015.

Copyright © David Zucchino 2004.

The moral right of David Zucchino to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-Book ISBN: 978 1 78239 686 4Paperback ISBN: 978 1 84354 283 4

Interior maps by Matthew Ericson.

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my father,First Sergeant Ernest Joseph Zucchino(World War II, Korea, Vietnam),who served with honor

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY MARK BOWDEN

ONE – CHARLIE ONE TWO

TWO – THE RIGHT THING

THREE – DOUBLE TAP

FOUR – PUPPY LOVE

FIVE – THE PLAN

SIX – A COVERT BREACH

SEVEN – THE PALACE GATES

EIGHT – SUICIDE AT THE GATES OF BAGHDAD

NINE – THE PARTY IS ABOVE ALL

TEN – GOD WILL BURN THEIR BODIES IN HELL

ELEVEN – GOING AMBER

TWELVE – CURLY

THIRTEEN – BIG TIME

FOURTEEN – CATFISH

FIFTEEN – MOE, LARRY

SIXTEEN – PLAYING THE GAME

SEVENTEEN – COUNTERATTACK

EIGHTEEN – THE BRIDGE

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

APPENDIX

NOTES ON SOURCES

FOREWORD

By far the most important and decisive part of the stunning American sweep of Iraq in 2003 was the surprise armored thrust into the heart of Baghdad. While pundits at home and around the world (myself included) were predicting a potentially bloody, protracted siege of Saddam Hussein’s capital, and while the notorious “Baghdad Bob” was before microphones in the Al Rashid Hotel denying that American forces were anywhere near the city, the Spartan Brigade, the Second Brigade of the Third Infantry Division (Mechanized), was blasting its way up the city’s central avenues. It was a perfect illustration of how history is usually made, not by planners and critics, but by brave men with their boots on the ground—or, in this case, Abrams tank treads. The Spartan Brigade’s thunder run became the turning point of the war both militarily and psychologically.

I have to say that I was not surprised to learn that my friend and long-time colleague David Zucchino was with those men. Zook is one of the best reporters of our generation, and he’s been putting himself at risk to get good stories for many years. He’s smart, fearless, tenacious, and (thank God) lucky. He survived one serious brush with death covering the war, and dove right back into the action. This book will outshine and outlast the flood of embedded memoirs of that war, because of both where he was and who he is.

We both started as reporters at The Philadelphia Inquirer almost a quarter century ago. Zook and I, the late Mark Fineman, Buzz Bissinger, Richard Ben Cramer, Mike Capuzzo, Bob Rosenthal, Lucinda Fleeson, and Joyce Gemperlein were among a group of young reporters at that paper who competed with one another each week to land the “Sunday Strip,” the story stripped over the masthead on the Sunday paper. It was the paper’s premier showcase for dramatic writing. The Sunday editor then was the late Ron Patel, a dashing man with a lusty appreciation for a lurid tale (for which reason, and others, he was nicknamed the Dark Prince). Philadelphia furnished plenty of opportunities for these stories—cannibal mass murderers, serial rapists, mobsters, animals and damsels in peril, madmen, shipwrecks, mystery, and gore. We called the stories Dirtballs. They were and are the bread and butter of newspaper writing. While other reporters were trying to master the arcana of state budgets or probing for malfeasance in City Hall, we were out looking for the sleazy stuff that would appease the appetite of the Dark Prince. You had to be fast to win the weekly contest, and you had to be good. You had to spot the small item with dirtball potential before anybody else, find the gory details, write it, and have it in Patel’s hands whole by Thursday afternoon—he was a stickler for freshness. We all had our moments of glory in this sweepstakes, but I think Zook was the master.

He went on to become the paper’s best foreign correspondent, winning a Pulitzer Prize for an amazing series of stories he wrote from South Africa before the overthrow of apartheid. I once had the chance to work with David in the Middle East. We spent a few days together in Jerusalem trying to cover the first Intifada, driving off together into the West Bank and Gaza. He was a veteran by then and I was a rookie. I vividly remember him behind the wheel of our rental at the crack of dawn, heading off from the walls of the Old City into Palestinian territory looking for trouble, remarking gleefully, “Look out, he’s got a car!” We always found trouble. Zook had a nose for it. He was getting ready to take off for some other hot spot, and he kindly stuck around for a few extra days to help me get acquainted with the turf.

I thoroughly enjoyed working with him, but I have to admit I was a little relieved when he departed. He was wearing me out. His motor ran in a faster gear than my own. He combined boundless energy with a bottomless appetite for action, and liked to stay up late in the bar drinking beer, swapping tales, and trying to understand the huge story unfolding all around us. I didn’t get a full night’s sleep until he was out of town.

When I wrote the first draft of Black Hawk Down in 1997, Zook had taken a serious career misstep. He had accepted the job of Foreign Editor, chained to a desk through long days and nights, trying to get other people to do what he could do better himself. It worked to my benefit, however, because he became one of the early enthusiasts for my story at the paper, and eventually helped me with it enormously. He edited that first draft into a crisp newspaper serial, so when I sat down to write the book version, I had the inestimable benefit of his earlier guidance. He performed a similar service when I wrote my book Killing Pablo, which also first appeared as a Zook-edited serial in the newspaper. I remember him telling me, “Next time, I get the story and you get the damn editing job.”

Well, this time Zook gets the story, and I’m lucky enough to have ducked doing the edit—not that he needs any help from me. Already with Thunder Run he’s got one leg up on my efforts. He was there.

And, as I expected, he has come back with the single best story of the Iraq War. Watching on TV, many of us had the impression that Baghdad’s resistance just melted away at the approach of American forces. Thunder Run will dispel that illusion. This was the most bitterly contested moment in the war, one that left thousands dead, including some very brave American soldiers. Zook’s writing captures the drama, the heroism, the fear, noise, confusion, horror, and, yes, the thrill of battle. It is a masterwork by a master reporter and writer. I’m proud to introduce it to you.

—Mark Bowden

War is neither magnificent nor squalid; it is simply life, and an expression of life can always evade us.

—Stephen Crane, War Memories

ONE

CHARLIE ONE TWO

Jason Diaz was worried about his tank. It had taken a terrible beating on the long, swift march up from Kuwait that spring. Roving packs of Fedayeen Saddam, the fanatic Iraqi militiamen in their distinctive black pajamas, had shot it up outside the holy city of Najaf and in firefights along the muddy Euphrates River. The tank’s pale tan skin was peppered with holes gouged out by automatic rifle fire and exploding grenades, leaving a splatter pattern of dinks and scrapes and blisters, like a chronic case of acne. The 1,500-horsepower turbine engine had sucked in several pounds of coarse sand and grit. The groaning twin tracks had been ground down by two weeks of firefights and ambushes as Diaz pushed the tank ruthlessly over the hard-pan deserts of southern and central Iraq. He and his crew had been on the move, day and night, for two weeks, and he badly needed a day—or at least a few hours—for maintenance and repairs and sleep.

Diaz was a tank commander, and his life depended on his tank. It was, literally, a mobile home for Diaz and his three crewmen—his gunner, his loader, and his driver. They slept on the decks, wolfed down lumpish MREs—meals-ready-to-eat—inside the turret, hunkered down in the cramped hatches on cold desert nights. The tank’s thick steel hull kept them alive; they had stayed buttoned up inside as RPGs, rocket-propelled grenades, exploded with heavy metallic jolts that made the cupola shutter, and as AK-47 rounds beat a steady ping, ping, ping on the two-inch-thick steel ballistic skirts. Diaz loved its squat, ugly frame, its bull-shouldered arrogance, even the rank sulfurous stench that permeated the turret each time the aft caps blew off the main gun rounds. The tank was a seventy-ton gas hog, getting a mere one kilometer per gallon, highway or city. It burned fifty-six gallons an hour at full clip and ten gallons an hour while idling. But for all its inefficient bulk, the tank was a $4.3 million killing machine. It was capable of ripping men in half with its coax—its coaxially mounted 7.62mm machine gun—and popping off enemy tank turrets three kilometers away with long sleek rounds from its 120mm main cannon. It was a mobile armory, hauling forty-one main gun projectiles, a thousand fat rounds of .50-caliber ammunition, and more than ten thousand 7.62mm machine-gun bullets. Pitted against an Iraqi army with three-decade-old Soviet tanks, the big pale beast seemed virtually invincible.

The M1A1 Abrams was designed for brutal conditions, and this particular model was a mule. It looked like a junkyard wreck by now, on this cool evening in central Iraq, but it had brought Diaz and his crew all the way from the Kuwaiti desert to the dull gray plains south of Baghdad. The entire Second Brigade of the Third Infantry Division (Mechanized), all four thousand tankers and infantrymen and medics and mechanics, was camped out, eighteen kilometers south of the capital on a grimy stretch of scrub flatlands in the shadow of a soaring highway cloverleaf. The division had just completed the fastest sustained combat ground march in American military history—704 kilometers in just over two weeks, and 300 kilometers in one twenty-four-hour sprint. It was April 4, 2003, and Jason Diaz from the Bronx—budding army lifer, husband of Monique, father of little Alondra and the twins, Alexandra and Anthony—was weary and filthy and longing to go home. But now, on this cold starry night, he was obliged to demand even more from his exhausted crew and his overextended tank. He had just been ordered to take them straight into Baghdad.

Diaz had received the OPORD—the operation order—in the dark that night. At his level in the chain of command, a mere staff sergeant in charge of just three men, he was provided no computer printout, no written battle plan. His platoon lieutenant simply called him over and said, with little elaboration, “We’re going into Baghdad at first light.” Then the lieutenant felt compelled to add, unnecessarily, Diaz thought, “Be ready for a fight.” The whole tank battalion was going—all thirty tanks and fourteen Bradley Fighting Vehicles and assorted armored personnel carriers of the Desert Rogues, more formally known as the First Battalion, Sixty-fourth Armor Regiment, which formed the core of Task Force 1-64. And Diaz’s well-traveled tank, part of the lead platoon of Charlie Company, would be squarely in the middle of the armored column.

Diaz was surprised by the sudden operation order, for there had not been the slightest hint that the brigade was going anywhere near downtown Baghdad. No American forces had entered the city; the war’s main front was still well south of the capital, where the Medina Division of the Republican Guard was defending the southern approaches. In fact, Diaz and the rest of the battalion had spent most of that day foraging south, blowing up Medina Division tanks and personnel carriers on a sort of combat joyride that some of the tankers were now calling the Turkey Shoot.

Long before “LD-ing,” before crossing what soldiers called the line of departure from Kuwait into Iraq sixteen days earlier, Diaz and his men had been told that they would stop short of Baghdad. The Second Brigade, nicknamed the Spartan Brigade, was a heavy-armor unit. The tankers had trained to fight in open desert, not in a city. The U.S. military strategy—as it had been briefed to Diaz, at least—was to surround Baghdad with tanks while airborne units cleared the capital block by block in a steady, constricting siege. The Pentagon brass was still spooked by the disastrous U.S. raid into Mogadishu ten years earlier, when American soldiers were trapped in tight streets and alleys and eighteen men were killed by Somali street fighters. But now, with no warning and with only a few hours to prepare, Diaz was being ordered to take his banged-up tank into a hostile city of 5 million Iraqis, a treacherous urban battlefield of narrow streets and alleyways.

The mechanics worked on the tanks all that night. There were four tanks in Diaz’s platoon, and two of them were in worse shape than his. They had debilitating track and battery problems. In fact, they were so degraded that the mechanics couldn’t get them battle-ready. They were scratched from the mission in the middle of the night. The platoon would have to go into the city at half strength. Diaz had been up all night with the mechanics, and now he was too agitated to sleep. He didn’t know anything about Baghdad. He didn’t know anything about the enemy in the city. He wasn’t afraid of combat or the enemy. He was afraid of the unknown.

On the same barren field, Eric Schwartz was also having a fitful night. Schwartz was a short, spare forty-one-year-old, the son of a Navy Huey gunship pilot who had won a Silver Star in Vietnam. With his clipped graying hair and studious manner, he looked more like a college professor than a soldier. He had a degree in education and a graduate degree in human resource development. Like most tankers, he was neither tall nor heavyset; trim, compact men fit more comfortably in the tight hatches. Schwartz had fought as a tank commander in Operation Desert Storm, and now, twelve years later, he had risen to battalion commander. A lieutenant colonel, he was the man in charge of the Rogue battalion, and now he was trying to make it through what was becoming the longest night of his life.

Schwartz had wrapped up the planning sessions for the mission at about 11:30 p.m. He walked out in the dark and climbed up on the deck of his tank to try to sleep. He stretched out there for a while, staring at the stars, his mind racing, and finally he gave up. He climbed down and strolled over to the tank crews. Nobody was sleeping. The tank commanders were talking quietly to their drivers and gunners, laying out details of the mission, their low voices like soft music in the dark. Schwartz went from crew to crew, patting backs, talking about families and food and home. He needed that human contact, and he thought his men did, too. He kept at it for a couple of hours, then went back to his tank deck and tried again to fall asleep. This time, he went down. Thirty minutes later, he woke up. It was nearly dawn. He was ready.

Schwartz had not expected to be preparing to fight his way into Baghdad so soon. His focus had been in the opposite direction, more than thirty kilometers south of the capital, where his battalion had spent most of that day, April 4, lighting up the Medina Division. This was the Turkey Shoot—what amounted to target practice, only with actual enemy tanks and armored personnel carriers instead of the rusted hulks the gunners had fired at on the target ranges in Kuwait and back home at Fort Stewart, Georgia. The Iraqis had hidden their outdated, Soviet-made personnel carriers and tanks—T-55s and T-72s, mostly—in garages, next to homes and schools, and in date palm groves. They were experts in camouflage, and much of the armor had survived coalition air strikes.

Many of the Iraqi regulars manning the vehicles had fled, so the Rogue battalion was firing on quite a few empty tanks and personnel carriers that day. The battalion had absorbed a few stray RPG attacks and small-arms rounds from Iraqi stragglers, but the biggest threat came not from the enemy but from the hot burning metal of exploding Iraqi vehicles. Abrams tanks normally fire at targets two or three kilometers away—the typical kill distance for the American tankers who had destroyed Iraqi tanks in the first Gulf War. But now Rogue’s targets were only a few hundred meters away, so close that the gunners could see the curling fronds on the date palm camouflage.

As the Abrams tanks tore into the Iraqi armor, the tanks and personnel carriers exploded. They didn’t just pop like firecrackers. They blew like bombs, the tank turrets spinning crazily and chunks of flaming steel and cooked ammunition hissing through the air. A shard of burning metal burned through one of Rogue’s Humvee trailers, setting a heap of gear on fire. Several Americans were cut and bloodied by flying metal, none seriously, and the drivers quickly learned to speed up to escape the barrage.

From his tank commander’s hatch, Schwartz had spotted an empty T-72. He got on the radio and said, “This one is mine.” He told his gunner to fire a SABOT round, a forty-five-pound, armor-piercing projectile with aluminum stabilizing fins and depleted uranium rod—an exceptionally dense metal ideal for penetrating military armor and heating it to molten metal. The round easily punched through the tank’s steel skin, but it didn’t pop the turret. Schwartz ordered up a HEAT round, a high-explosive antitank projectile tipped with a shaped charge. It turned the T-72 into a bonfire. Schwartz’s driver had to speed away to avoid the firestorm.

But at one point Schwartz got tagged. He was passing a burning Iraqi vehicle about 150 meters away, and he told his loader to keep an eye on it. It seemed ready to explode. An instant later, it blew. Schwartz felt a blast of heat and ducked down into the cupola. He popped back up to look around and was slammed down to the bottom of the turret. He briefly lost consciousness. His loader shook him roughly and shouted, “Sir! Sir! Sir! Get up! Get up!” Schwartz came to and looked at his shoulder. A hot shard of metal had smacked into it. The shard burned him and hurt like hell, but Schwartz was okay. He got back up in the turret and moved on.

The shoulder was still aching later that afternoon, when Schwartz got a radio call from Colonel David Perkins, the Second Brigade commander. Perkins wanted to see Schwartz right away at the brigade command tent. Schwartz had just finished the Turkey Shoot, and he and his men were beat. He had hoped to give them time to rest, repair their vehicles, perhaps even grab a few hours’ sleep. They had barely slept on the long slog up from Kuwait. Schwartz was a disciplined officer, and when his commander summoned him, he reported right way, no matter how tired and miserable he felt. A slight figure in his green Nomex tanker overalls, Schwartz hustled over to the command post at the edge of the dusty field along the highway.

Inside, Perkins, a slender officer with an erect bearing, was hunched over a map, his head down. Normally, the command post was a loud, busy place, a collection of communications vehicles backed up end to end and covered with canvas. But now it was quiet, and the headquarters staff officers and battle captains were milling around, silent. Schwartz took off his helmet and flak vest. An officer cleared off the map board in front of Perkins. The icons showed Second Brigade’s battalions clustered south of the city, the division’s First Brigade camped to the west at the airport, and the Third Brigade set up northwest of the capital. A division of U.S. Marines was still on the move southeast of the city, off the map. Baghdad itself was a blank expanse of enemy forces, size and capability unknown.

Perkins looked up. “At first light tomorrow,” he told Schwartz, “I want you to attack into Baghdad.”

Schwartz heard a whooshing noise in his ears. He felt disoriented. He had just spent several hours in a tank, pushing south, ducking hot shrapnel, and the last thing on his mind was going north into Baghdad. He had always assumed airborne units would clear the capital at some future date, with the Spartan Brigade setting up blocking positions outside the city.

“Are you fucking crazy . . . ?” Schwartz blurted out, then added, “. . . sir?” He waited for the other officers to laugh.

There was silence.

“No,” Perkins said. He wasn’t the type of commander to kid around. “And I’m coming with you. We have to do this.”

Just after dawn the next morning, April 5, the entire battalion was lined up on Highway 8 south of the capital, engines gunning, weapons primed, the squat tan forms of the tanks and Bradleys bathed in gold morning light. Jason Diaz’s tank, radio call sign Charlie One Two, was fifteenth in the order of march. He was up in the commander’s hatch, awaiting the order to move out, when his driver radioed up from the driver’s hole tucked below the turret. “The AIR FILTER CLOGGED light is on,” he said.

They hadn’t even launched the mission yet, and already the tank was balking. Diaz was anxious enough—and now this. He climbed down to check it out and saw his platoon leader, First Lieutenant Roger Gruneisen, inspecting his tank. The lieutenant’s right track was damaged and the cooling tubes were worn. Every time the track turned a rotation, it made a horrible clanking sound. Gruneisen looked at Diaz and asked, “You think we’ll make it?” Though Diaz was an enlisted man and Gruneisen was an officer, Diaz had more experience as a tank commander. He didn’t want to lie. “Really, sir,” he said, “ I’m not sure.” And that was the honest truth.

Diaz respected the lieutenant too much to try to bullshit him. Gruneisen was a platoon leader who trusted his men and let them do their jobs. He was the kind of man that Diaz, a Latino from the Bronx, probably never would have known if he hadn’t joined the military. Gruneisen was a white southerner, a pale young twenty-four-year-old, with a shaved head and a soft Kentucky twang. He was a West Point man, focused and resolute, commissioned less than two years earlier.

Diaz, twenty-seven, had already put in eight years and was thinking about becoming an army lifer. He had drifted aimlessly after graduating from John F. Kennedy High in the Bronx, working odd jobs in Puerto Rico before wandering into an army recruiting station one day. The recruiter showed him videos of various military MOSs, or specialties—medic, personnel, supply. Then he put on the tanker video. Diaz saw the thermal sights and the computerized targeting system and all the other high-tech turret gadgets. He watched a tank pulverize targets, spitting out awesome bursts of orange fire from the main gun tube. He thought it would be cool to blow things up. He signed up to be a tanker.

Diaz had a deep affection for his current Abrams, which he had trained on and fought in for the previous six months. He and his gunner, Sergeant Jose Couvertier, had nicknamed it Cojone Eh? The phrase had no literal English translation. Essentially, it meant “Yeah, right”—a skeptic’s challenge. All the tankers had spray-painted their main cannons with leering names that suggested a particularly aggressive and retributive brand of patriotism: Apocalypse and Crusader,Courtesy of the Red White and Blue and Cry Havoc and Let Slip the Dogs of War. Charlie One Two’s nickname just happened to be more esoteric than most.

Standing next to Diaz on Highway 8, Gruneisen did not seriously consider aborting his platoon’s mission. They were only going seventeen kilometers from their staging area south of the city, a straight shot north up Highway 8 and then west on 8 where the highway curved toward the international airport. There, the battalion would link up with the division’s First Brigade, which had seized the airport the day before, rechristening Saddam International as Baghdad International.

This was an armored reconnaissance mission. Armor recon was just what it sounded like: the battalion was to smash through Baghdad’s defenses, drawing fire and shooting back in order to probe the Iraqis’ defenses and tactics—to determine, violently, how Saddam Hussein intended to defend his capital. It was recon by fire.

Gruneisen was surprised by Highway 8. It was a modern, divided superhighway, nothing like the rutted roads and sandy tracks the battalion had plowed through down south. It looked like an American interstate highway. From what he could see, it hadn’t been badly damaged by coalition air strikes. It was two lanes wide in some places, three in others. The lieutenant thought his ailing tanks could last seventeen kilometers on that smooth, flat surface.

He turned to Diaz. “Let’s give it a shot,” he said, as if there were any alternative.

Within minutes, the order came to mount up and move out. The column lurched to life. Foul black smoke erupted from the Bradley engines. The tank tracks tore neat little grooves in the asphalt, clanking and grinding, and the roadway was milky white with blowing dust. The lead tank chugged past the final American checkpoint and a voice came over the radio net: “You are now entering Indian Country.”

Diaz gave his driver the order to pull forward, with Gruneisen on his wing. Already, they could hear the soft pop of small-arms fire up ahead. They had been in combat for the previous sixteen days, off and on, but still they felt that tight, queasy spasm in their bellies that always rose up, urgent and bitter, just before a fight. It passed quickly, and Gruneisen fell easily into the order of march. The final checkpoint was fading into the yellow dust behind them when the driver radioed the lieutenant that the oil filter warning light had suddenly started flashing.

At the head of the column, First Lieutenant Robert Ball scanned the roadway, left to right, right to left, searching for threats. As the commander of the lead tank, he felt as though he were perched on a slow seventy-ton target, especially standing up in the cupola, his head and shoulders exposed. He wore a CVC—a combat vehicle crew helmet—made of bullet-resistant Kevlar and a small tanker’s flak vest, but he knew a single well-placed round from an assault rifle, so useless against a tank, was more than enough to kill him in an instant.

Ball had been selected to lead the column not because he had a particularly refined sense of direction but because his tank had a plow. The battalion was expecting obstacles in the highway. Like any motorist, Ball had been lost a time or two while driving in the States. Even so, he thought of himself as pretty good with a map, and he had carefully studied his 1:100,000 military map of Baghdad and Highway 8. He could see how the highway bent west toward the airport, cutting a slice through southwest Baghdad. But the map had no civilian markings—no exit numbers, no neighborhoods. Ball was concerned about missing his exit to the airport at what everybody called the spaghetti junction, a maze of twisting overpasses and on-ramps on the cusp of downtown Baghdad. He found himself longing for a simple AAA tourist map.

Ball, twenty-five, had never been in combat prior to the firefights in the southern Iraqi desert. He was a slender, soft-spoken North Carolinian with a girlfriend back home and a twin brother in the service. He had spent two years in the North Carolina Army Reserves before entering West Point and earning a commission in 2001. He had been promoted to first lieutenant just four months earlier, and now he was a platoon leader in the same company that Rick Schwartz had commanded in the first Gulf War.

Ball had killed a man for the first time a few days earlier. In fact, he and his crew had killed quite a few enemy fighters down south, and he found it an unnerving experience. He couldn’t remember them all, but for certain ones he recalled the most curious details—the stunned look on the dying man’s face, the smell, the hazy air, the intense emotional attachment to the intricate ballet of combat. He felt an abiding sense of regret, which he had anticipated. He had met with a chaplain in Kuwait several times, seeking reassurance. The chaplain had told him that killing the enemy was part of a just cause; it would actually save lives in the long run and improve the prospects of thousands of Iraqis. The little sessions with the chaplain had put Ball at ease, and now he was primed for the fight.

Ball’s map was clipped to the top of the commander’s hatch, next to his .50-caliber machine gun, as he led the column up the highway. It was an unremarkable stretch of roadway. In the early morning light, everything was bathed in a monochrome grayish tan—the overpasses, the access roads, the squat houses and multistory apartment buildings set far off the highway. On either side were open stretches of packed dirt and dust-choked weeds, providing clear fields of fire.

Ball had been rolling only a few minutes when his gunner, Sergeant Geary LaRocque, spotted the first targets of the morning. A dozen Iraqi soldiers in green uniforms were leaning against a building, chatting, drinking tea, their weapons propped against a wall. They were only a few hundred meters away, but they seemed oblivious to the grinding and clanking of the approaching armored column.

“Sir, can I shoot at these guys?” LaRocque asked.

The rules of engagement said anyone in a military uniform or brandishing a weapon was a legitimate target. They didn’t say anything about announcing yourself before firing.

“Uh, yeah, they’re enemy,” Ball replied.

In southern Iraq, the men Ball’s crew had killed were murky green figures targeted at great distances by the tank’s thermal imagery system. Their body heat gave them away, creating eerie human shapes on the thermals. But now these soldiers highlighted against the dark building along Highway 8 were in living color. Through the tank’s magnified sights, Ball could see their eyes, their mustaches, their steaming cups of tea.

LaRocque mowed them down methodically, left to right. As each man fell, Ball could see a puzzled expression cross the face of the next man before he, too, pitched violently to the ground in a pink spray. The last man managed to flee around the corner of the building. But then, inexplicably, he ran back into the open. The gunner dropped him.

The clattering of the tank’s coax, its rapid-fire medium machine gun, seemed to awaken Iraqi soldiers posted up and down the highway. Gunfire erupted from both sides—AK-47 assault rifles and rocket-propelled grenades, followed minutes later by recoilless rifles and air defense artillery in direct fire mode.

Ball was surprised by the sudden intensity of fire. He was accustomed to the way the Iraqis had fought down south, which was mostly pop up, shoot, run, and hide. But now, on Highway 8, they were standing their ground—and the column had only traveled about a mile beyond the final checkpoint. Ball could now see that the Iraqis had built an elaborate network of trenches and bunkers on both sides of the highway. He saw bright white muzzle flashes, little sparks of light all the way up the shoulders of the highway. From alleyways and rooftops, men with RPGs were launching grenades toward the column, flaming red balls of light trailed by spirals of gray smoke.

The first main tank round of the mission was fired by Sergeant Jeffrey Ellis, an easygoing Alabamian who was the gunner on the third tank in the column. Ball had radioed back to Ellis that a group of armed men had just fired an RPG and then ducked into a tiny cinder-block hut on the right side of the highway. He wanted them taken out. Sergeant First Class Ronald Gaines, the tank commander, radioed the company commander, Captain Andy Hilmes, and said, “We’ve got some guys running into a little building. Request permission to fire the main gun.” Hilmes responded, “Roger, fire main gun.”

Through his magnified sight, Ellis could see men piling into the hut. There were perhaps two dozen of them. The main gun was in battle-carry mode, meaning it was preloaded, in this case with an MPAT round, a multipurpose antitank projectile. It was a new piece of ammunition that had not been used in combat before the Iraqi war. Ellis thought it was just as effective as a HEAT round and a little more versatile. When set to ground mode (it could also be used against helicopters), the MPAT was designed to penetrate a target and explode inside. Ellis traversed the gun tube, got a laser reading of 610 meters, and put the targeting reticle’s tiny red crosshatches on the hut. He squeezed the trigger on the gunner’s power control handles, which all the gunners called cadillacs, for the original manufacturer, Cadillac Gage. “On the way!” he announced. The MPAT round reduced the hut to dust, unleashing a cloud of gray smoke twice the size of the structure. Even before the crews in the tanks behind him announced over the radio that nothing was moving inside, Ellis knew he had killed them all. Over the net came calls of congratulations: “Great shot! . . . Good shot! . . . Hell of a shot!”

Suddenly trucks and pickups and taxis were speeding toward the overpasses from access roads, dropping off gunmen. They stood at the roadside, completely exposed, and fired AK-47s from the hip. Ball opened up with his .50-caliber machine gun and the gunner unleashed the coax, tearing into the gunmen and sending them tumbling into the dirt. The tank gunners started lighting up the vehicles in fiery red explosions from HEAT rounds, and more HEAT and MPAT rounds tore into the roadside bunkers. The battle was on.

In the command tank a short distance behind Ball, the battalion commander, Rick Schwartz, was determined to keep the column moving. The last thing Schwartz wanted was to get pinned down or be drawn into an extended firefight. The night before, he had instructed his officers and NCOs to keep the convoy moving at fifteen kilometers per hour, with strictly enforced fifty-meter intervals between the vehicles. The drivers were under orders to keep a steady pace; moving faster or slower would break the column and permit enemy vehicles to slice in and attack the tanks in their vulnerable rear exhaust grills. The track commanders and gunners had their own orders: the lead gunners were to try to kill everything they saw, then pass the targets back to the trailing tracks. Schwartz wanted his men talking to one another, describing exactly what they were shooting at and what still needed killing.

Schwartz was still trying to determine exactly what he was up against. The brigade’s S-2 shop, the intelligence guys, had not been able to tell him much. In fact, when Schwartz had asked for specifics about enemy strength and positions the night before, he got a vague, long-winded answer. Finally Schwartz said, “So you don’t know shit about the enemy in the city, do you?” The intelligence officer told him, “No, nothing really.”

Nor were the intelligence officers entirely certain how badly coalition air strikes had degraded Saddam Hussein’s forces, what weapons the Iraqis had, or how determined they were to stand and fight. The brigade’s scouts, who normally went out ahead to conduct enemy surveillance, had not ventured north. It was too dangerous. And if any Special Forces teams had been into the city, Schwartz certainly didn’t know what, if anything, they had discovered. He was on his own.

Schwartz did have satellite imagery providing a black-and-white photographic bird’s-eye view of Baghdad. But the imagery was several days old, perhaps a week old or more. Even if it had been shot that morning, it would not have told Schwartz where the enemy was dug in. Satellite imagery could not pick up camouflaged bunkers or RPG teams hiding in alleyways and second-story windows. The division had tried to order up a pass by a UAV, an unmanned aerial vehicle—a spy drone—for real-time battlefield photos, but for various bureaucratic and technical reasons it never happened.

To the best of Schwartz’s knowledge, Highway 8 was not blocked by any concerted Iraqi attempt at barricades. The Iraqis certainly had not blown the bridges and overpasses leading into the capital, although American military planners had expected them to try. Based on the most recent satellite imagery, and on reports from American pilots who had flown over the city, the highway was clear and relatively unscathed by coalition air strikes. There was no safer or faster surface for tanks than good old highway asphalt—in this case, asphalt helpfully marked with wide traffic lanes and highway signs in Arabic and English. By all indications, the Iraqis had left the back door to the capital wide open. It was like leaving Interstate 95 and the Capital Beltway open for an enemy tank invasion of Washington, D.C.

In issuing his order to Schwartz, Colonel Perkins had said, “The task is to enter Baghdad for the purpose of displaying combat power, to destroy enemy forces—and to simply show them that we can.” Essentially, what Perkins had ordered up was a thunder run, a lightning armored strike straight into the capital. The American military had been conducting thunder runs since the Vietnam War, where the term had originated. The secure artillery fire bases set up in Vietnam in the mid-1960s had been code-named Thunder I, Thunder II, and so on. The Viet Cong, attempting to disrupt U.S. supply convoys plying the highways between the artillery bases, sent out guerrilla teams at night to cut the roads and set up ambushes. To keep the arteries secure, American commanders dispatched columns of tanks and armored vehicles up and down the roads at dusk. The columns moved at high speeds, blasting away on both sides of the highway to draw enemy fire—what the military calls recon by fire. Soon any rapid dash through hostile territory became known as a thunder run.

As the Rogue column came under fire on the morning of April 5, Schwartz got a good look at the enemy. There were hundreds of them, perhaps thousands. Some were in uniform. Some wore civilian clothes, or a mix of jeans and green army vests, with machine-gun coils slung bandolierstyle over their shoulders. There were Fedayeen Saddam militiamen in baggy black pajamas and—Schwartz not did realize this until later—Syrian mercenaries brought in by buses from Damascus, their pockets stuffed with Iraqi dinars. Many of the Syrians, along with armed Jordanians and Palestinians, were jihadis, Muslim fundamentalists eager to fight a holy war against infidel invaders.

There was an armored personnel carrier here and there, but no tanks—and probably nothing capable of destroying a tank or Bradley. But the recoilless rifles could put a serious dent in an armored personnel carrier and were a real threat, especially to the combat engineers firing their M-4 carbines from the exposed hatches of the M113 armored tracks. Schwartz had ordered the engineers to fire at snipers in upper-story windows or on rooftops. The tanks had trouble elevating their gun tubes that high. If any of his guys were going to get killed, he feared, it would be the engineers.

The Iraqis seemed to have no training, no discipline, no coordinated tactics. It was all point and shoot. A few soldiers would pop up and fire, then stand out in the open to gauge the effects of their shots. The big coax rounds from the tanks and Bradleys sent chunks of their bodies splattering into the roadside.

Nor did the Iraqis seem to appreciate the lethal and accurate firepower of the tanks and Bradleys. The gunmen fired from bunkers, their muzzle flashes exposing their positions. From hundreds of meters away, nearly out of sight, the tank gunners peered through their optical sights and fixed the red aiming dots and crossed hash lines of their reticles—their targeting systems—on the bunkers. They squeezed red trigger buttons on their cadillacs and the bunkers exploded with a heavy whump and a shudder as the HEAT rounds detonated.

Few of the Iraqi fighters demonstrated much command of basic combat maneuvers. They would bunch up in the alleyways, firing wildly. The tank loaders would shove an MPAT round into the breech and set the proximity fuse for ten or twelve meters. The gunners would fire into the mass of men and the broad arc of the explosion would send their shattered bodies airborne.

Gunmen crouched behind walls made of brick or cinder block, apparently unaware that not only the tanks and Bradleys but also the tank commanders’ .50-caliber machine-gun rounds could pound the walls to dust in seconds. The gunners watched the fighters’ bodies explode and disintegrate along with whole sections of the walls. Other fighters hid in thick stands of date palm trees, leaping out to launch RPGs. Some of the tank and Bradley gunners had discovered down south that a tree hit with a fifty-pound shell unleashes a wave of flying wood shards. It was wood shrapnel. The gunners tore into the date palms along Highway 8, shattering the trunks and impaling anyone crouched behind them.

The tanks and Bradleys had a rhythm now, pounding, pounding, pounding. They were killing people by the dozens, but still the enemy kept coming. By now, gunmen were up on the overpasses, firing straight down on the tank and Bradley hatches. More and more vehicles were appearing. There were little Japanese sedans and bulky 1980s-era Chevrolet Caprices, some of them stuffed with husbands and wives and kids staring wide-eyed at the column as the cars zoomed past in the southbound lanes beyond the median. But other cars and pickups were packed with soldiers in uniform or men in civilian clothes blasting away with AK-47s poking out the windows. There were tan military troop trucks and “technicals”—white Toyota pickups with machine guns or antitank rockets mounted in the beds.

It occurred to the battalion’s S-3, the operations officer, Major Michael Donovan, that the battalion was winging it. They certainly had not trained for urban warfare—much less for this battle, which involved urban areas at the highway’s margins, but also stretches of wide-open cross-country highway. It was like fighting on the New Jersey Turnpike. Donovan, thirty-eight, a slender, sharp-featured man, was the son of a Vietnam veteran, a Citadel graduate, and a student of military history. It dawned on him now that Rogue battalion was rewriting the army’s armor doctrine on the fly. He himself was certainly rewriting the role of an operations officer. His job was planning and organization. But now he was in the commander’s hatch of an Abrams—and firing an M-4 carbine at men in ditches on the side of a superhighway. He thought: Holy shit, I’m the S-3 and I’m shooting dudes with a rifle!

This was nothing like Donovan had experienced in Operation Desert Storm in southern Iraq a decade earlier. Back then, his tank never got closer than two kilometers to an Iraqi tank. That was a standoff war, distant, removed, impersonal. This war, Schwartz had warned him the night before, would be unique: “This isn’t going to be anything like Desert Storm.” Now, on Highway 8, Donovan could see the faces of Iraqi fighters. His father had told him stories of Viet Cong guerrillas smiling as they fired. Now he was seeing young Iraqi faces, and their dominant emotion was fear. They looked terrified. Donovan spotted several armed soldiers in a bunker, just beyond the guardrail. They were huddled and afraid. He didn’t want to kill them, but he had to. They were the enemy. He opened up with the M-4 and watched them topple.

More carloads of civilians were beginning to appear, complicating what the tankers called target acquisition. Donovan was worried about civilian casualties—what the military, in its wonderfully clinical articulation, referred to as collateral damage. The civilians were getting into the middle of the fight. The crews were under strict orders to identify targets as military before firing. They were supposed to fire warning shots, then shoot into engine blocks if a vehicle continued to approach. Some cars screeched to a halt. Others kept coming, and the gunners and tank commanders ripped into them. Some vehicles exploded. Others smashed into guardrails, their windshields streaked with blood. The crews could see soldiers or armed men in civilian clothes in some of the smoking hulks. In others, they weren’t sure. Deep down, they knew they were inadvertently killing civilians who had been caught up in the fight. They just didn’t know how many. They knew only that any vehicle that kept coming at the column was violently eliminated.

At one point, a white minivan sped alongside Donovan’s tank. The driver, a middle-aged man in civilian clothes, made eye contact and gave Donovan a manic “don’t shoot” gesture. Donovan motioned for him to get out of the way. As the van pulled away, Donovan saw that three uniformed soldiers with guns were lying in the rear bed. He radioed ahead to the front of the column. Minutes later, he watched one of the gunners with the fire support team pulverize the minivan as it tried to escape down an exit ramp.

At the next interchange, Donovan spotted a technical—a red Nissan pickup with a Soviet-made heavy machine gun mounted in the truck bed. A young man was firing the gun at the column, his black hair blowing wildly, as the Nissan sped across an overpass. Donovan screamed, “Oh, shit!” and yelled for the loader to open up with his M-240 medium machine gun. Donovan fired his M-4. They missed, and the technical got away.

The technical vehicles worried Lieutenant Colonel Schwartz because the drivers seemed so fearless and reckless. A few seemed determined to ram the column, driving straight toward the massive tanks and Bradleys before the coax rounds shattered their windshields and sent the vehicles careening into the guardrails. Schwartz was worried, too, about antitank weapons. He thought he had spotted a couple of American-made TOW missiles—tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided missiles—lethal weapons designed to destroy armored vehicles including American tanks and Bradleys.

Still, he felt confident. The lead tracks were radioing back to other tracks, giving them “triggers” to prepare to fire on technicals speeding up from the rear flanks. Schwartz’s air liaison officer was in his ear all morning, radioing with updates from the air force pilots circling overhead, tracking technicals and trucks pouring in from the crowded neighborhoods on either side of the highway.

The column was moving steadily. Nobody was stopping or even slowing. The tracks were passing on targets, handing off, just as Schwartz had ordered. Every single vehicle in the column had been blistered by RPGs or recoilless rifle rounds and thousands of rounds of small arms, but everybody was still intact and moving. Some of the RPGs had detonated on the gear and rucksacks stored on the tracks’ external bustle racks, and now the stuff was on fire. Most of the crews just let it burn.

Schwartz was laying down suppressive fire with his .50-caliber, shouting into his radio microphone. He was repeating himself now, but he wanted his message drummed into his soldiers’ brains: “Pass ’em off . . . pass ’em back . . . keep moving . . . keep the momentum.” The column, still intact, still paced and measured, rumbled up Highway 8. The staff officers back at the brigade operations tent could mark its progress on their computer screens, the column represented by tiny blue icons that inched, slowly, inexorably, north toward Baghdad.

TWO

THE RIGHT THING

As their tank approached the final checkpoint on Highway 8, Lieutenant Gruneisen’s crew was blasting the heavy metal song “Creeping Death” by Metallica on speakers inside the turret. They had nicknamed their Abrams Creeping Death because they all loved the song, which they thought evoked something sinister and lethal. That’s how they felt going in that morning. Even so, the mood was oddly buoyant inside the turret—buoyant, but also focused and determined, with just a whiff of sweaty anxiety. The crewmen always cranked up the music going into a mission to jack them up, to blow away the butterflies and get them in the mood to destroy the enemy.

It seemed to the crew’s gunner, Sergeant Carlos Hernandez, that they had been killing people for a long time, even though it had been barely two weeks. Hernandez had never been at war before, but he had discovered down south that time slowed down in combat. So many things happened all at once that it was almost as though time had to somehow pause and expand in order to accommodate it all. This enabled Hernandez to recall with utter clarity what it was like to kill a man. After the very first time, outside Najaf, he was pumped up and mournful at the same time. That conflicted feeling stayed with him even after he’d killed a few more people, but after a while he just got numb.

Other guys in his company had different reactions. Once, also outside Najaf, they were pounding an Iraqi bunker complex with tank cannons when they saw an Iraqi soldier leap up, throw down his weapon in disgust, and stalk off. The man had almost escaped the kill zone when an American mortar crashed down right on top of him, a direct hit. The soldier’s body disintegrated. Everybody laughed—not necessarily at the man’s brutal death but at fate, and how a guy who had decided to just walk away from a fight got nailed anyway.

Hernandez had thought a lot about death back in Kuwait. He was Catholic—not exactly a churchgoer but enough of a Catholic to be familiar with the phrase, “Thou shalt not kill.” He had sought out the battalion chaplain in Kuwait, for he wanted to make sure he was right with God in case he had to kill somebody. He and the chaplain had three or four good heart-to-heart sessions. Hernandez asked why people went to death row in the real world for murder but got medals in war for killing other human beings. The chaplain told him it boiled down to good and evil, and evil had to be conquered. Hernandez asked how the Iraqis justified killing to their God, their Allah. The chaplain sidestepped the question and told him that Saddam Hussein was evil and had killed thousands of his own people. Ending his regime would save lives. He reassured Hernandez and said, “You’re doing the right thing.”

Hernandez decided then that he was going to do whatever was necessary to keep his crew alive and to get everybody back home safely, himself included. Twenty-seven years old, he was a family man these days, far removed from the restless, drifting kid he had been after he dropped out of high school in Tampa to work as a carpenter on a construction crew. Joining the army had given him structure, and marrying Kimberly, his high school sweetheart, had settled him down. If he had to kill somebody to get home safely to Kimberly and his little boy, Carlos Anthony, and his daughter, Louise Marie, that’s what he would do.

As soon as the tank crossed the checkpoint on Highway 8, the crew killed the music. The lieutenant shouted, “Test fire weapons!” and Hernandez fired a few bursts of coax, which relaxed him and reassured him that everything was going to be okay. Then he heard the driver tell Lieutenant Gruneisen that the oil filter light was on. He radioed his buddy in Charlie One Two, Jason Diaz—Hernandez and Diaz and their wives played dominoes together back home at Fort Stewart—and told him, “Man, this doesn’t look too good.”

Then the crews heard Lieutenant Ball’s radio voice at the head of the column announce “Contact!” The gunmen in the bunkers opened up on them, and the crew got straight into the fight. Up in the turret of Charlie One Two, Diaz started working the .50-caliber, pumping rounds into the bunkers and into technical vehicles trying to race up the on-ramps and onto the overpasses. His gunner was hosing down dismounts—foot soldiers—with the coax, keeping them away from the column. Diaz feared dismounts would try to get close enough to the tank to pitch a grenade down the turret.

They were approaching the first overpass when Diaz felt a concussion rock the tank. He was wearing his CVC helmet, which muffled even the earsplitting booms of the 120mm main tank cannons, but still he could feel a shock wave washing over the turret. It felt like the concussion from a main gun, and he thought that perhaps Lieutenant Gruneisen in Charlie One One—Creeping Death—had pulled too close to him and fired over his back deck.

Diaz radioed the lieutenant and asked whether he had fired his main gun.

“Negative,” Gruneisen said.

“Can you look at my rear and see if anything’s smoking?”

The air was black with smoke from burning vehicles and bunkers and the exhaust from the Bradleys. Gruneisen couldn’t see much. Diaz’s tank seemed fine.

“Keep going,” he told Diaz.

Moments later, Gruneisen heard his ammo loader, Private First Class Donald Schafer, say, “Sir, something has hit One Two.”

Gruneisen looked again and saw a trail of gray smoke snaking from the rear grill. Some sort of fluid was dripping underneath the tank.

Inside Charlie One Two, Private First Class Chris Shipley shouted to Diaz from the driver’s hole, “The fire warning light is on!” And then, “The emergency lights are on!” The whole driver’s control panel was flashing.

Diaz was reporting the malfunction over the company net just as Gruneisen radioed and told him, “It looks like something hit you in the back, right above the grill!”

Diaz wanted to keep going and try to hobble all the way to the airport, but then Shipley radioed again from the driver’s hole: “The tank just aborted.”

The engine shut down. They were slowing to a stop. Diaz didn’t want to stop under the overpass and expose the stricken tank to enemy fire from above. He willed the tank forward, shouting at Shipley to try to keep it moving long enough to clear the overpass. They rolled on and came to a rest just north of the bridge, in the far left lane of Highway 8.

Diaz looked at his rear deck. Orange flames were shooting up out of the grill. He couldn’t believe it. He had never pictured an Abrams tank as helpless, as a victim. The entire brigade had had just one tank disabled by enemy fire in the entire war. Two days earlier, a fire in a tank’s auxiliary power unit, triggered by an RPG hit, had been quickly put out and the tank recovered and repaired. Even under punishing conditions and chronic parts shortages, the brigade had lost only 15 percent of its tanks to repairs at any given time. But now the back of Charlie One Two looked like a little bonfire. Diaz cursed and gave the order for the fire drill—the same drill they had practiced endlessly at Fort Stewart and in the Kuwaiti desert. He tried to sound calm as he hollered, “Evacuate tank!”

The defining characteristic of combat is chaos. No operation plays out the way it was planned. The purpose of training is to bring order to chaos, to condition men to react in prescribed ways, no matter what the emergency. On Highway 8, the battalion’s training kicked in. Diaz’s crew evacuated the tank and took up fighting positions. Gruneisen pulled his tank forward to protect the stricken tank’s northern flank. The Charlie Company commander, Captain Jason Conroy, moved his tank ahead of Gruneisen’s to provide more combat power, and the trail platoon set up a perimeter of armored vehicles to protect the rear.

Diaz and his crewmen were now exposed. It was a shock to be down on the smoky highway, out of the protective cocoon of the tank and its thick steel hull. The air smelled of cordite and burning fuel. It stung their nostrils. The crewmen heard rounds pinging off the sides of the tank and realized they were under fire. Gunmen in the crease of the overpass, where the bridge abutment meets the underside of the elevated runway, were firing down on them. Shipley, the driver, had fired so many M-4 carbine rounds that he was out of ammunition. He saw an AK-47 on the roadway, picked it up, and got it to work. He was firing away toward the overpass when one of the tanks traversed and cut down the gunmen in the crease with a burst of coax.

The tank fire was behaving strangely now. When Charlie One Two aborted, its fire protection system kicked in automatically, spraying the fire with Halon, a chemical retardant designed to rob flames of oxygen. That doused the fire for a moment, but soon it came back to life. Diaz jumped down to the left side of the tank and yanked the red emergency fire handle, setting off another round of Halon. The fire smoldered.

While his crew laid down suppressive fire, Diaz got on the back deck and inspected the rear grill. He opened up the rear compartments and saw that all the VEE packs—ventilation filters made of aluminum and filter paper with stiff, accordion-like folds—were on fire. In the lower compartments, the tank’s batteries were melting. Fuel was pouring onto the highway. It was bad, and Diaz knew it. But he also knew an Abrams was nearly invincible, and the only other brigade tank to catch fire in Iraq had been rescued with minimal damage.