Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

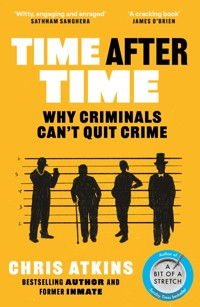

FROM THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF A BIT OF A STRETCH 'It's a cracking book. He really can write' James O'Brien, LBC 'Eloquent, witty, engaging and enraged ... the most important book you'll read this year' Sathnam Sanghera 'Brings a unique perspective, an unflinching eye and a dark sense of humour to hidden stories from the underbelly of the British justice system' Rafael Behr Our justice system allows a man to escape prison by pretending to be his twin brother. It lets someone live in luxury hotels for nine months masquerading as the Duke of Marlborough. It sends a man back to prison for not attending a party. How do these things happen, and why is it that the only thing harder than being in prison is staying out of it? Featuring funny, wild and poignant stories, Time After Time exploits former inmate and documentary maker Chris Atkin's unprecedented access to the criminal underworld to understand why the system actually makes reoffending all but inevitable for ex-prisoners.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 499

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Chris Atkins is a BAFTA-nominated film-maker. His documentaries Taking Liberties and Starsuckers were critically acclaimed and made front-page news. He directed the documentary film Who Killed the KLF? and has also worked extensively with Dispatches for Channel 4 and BBC Panorama. Following his release from prison, he is now back in North London, filming documentaries and writing.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Chris Atkins, 2023, 2024

The moral right of Chris Atkins to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 4 697

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 468 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Prologue

Introduction

1 ‘Gavin’

2 Ed

3 Josh

4 Jojo

5 Jake

6 ‘Harry’ and ‘Ingrid’

7 Alex

8 ‘Sandra’ and ‘Lee’

9 Steve

10 Simon

11 ‘Alan’

12 ‘Eric’

13 Marc

14 Carl and Karl

Conclusion

Epilogue

Appendix

Acknowledgements

Endnotes

Index

For Plamena and Kit

Preface to the Paperback Edition

One of the unforeseen challenges I faced with this book was that interesting things kept happening to my contributors. No sooner had I finished off a chapter then the subject would invariably be arrested, or released, or told to do something even more ridiculous by the criminal justice system. After missing three deadlines I had to draw a line in March 2023 and actually finish the hardback edition or it would never have hit the shelves. Consequently, several stories end slightly unsatisfyingly. We leave Josh preparing for his crunch appearance before the parole board, which might overturn his four-year wrongful imprisonment, while Ed is insisting that he’ll remain inside until the end of his full sentence as he was so sick of being recalled unfairly.

Following the initial publication in September 2023 I’ve been approached by dozens of readers demanding to know what’s happened to the contributors in the intervening time. Fortunately, I’ve kept in touch with most of the offenders featured in this book (I think a couple even have me on speed dial), so I’ve written a bonus chapter for the paperback edition to update on recent developments. It’s a bit like the ‘what happened next’ moment in a film’s credits, which reveal that one of the characters ran for president while another got a life sentence.

While this coda provides some cheering news about the contributors, the issues raised in the book have only got worse in the last year. As I type these words in April 2024, prison overcrowding has got so bad that the government is now releasing prisoners up to two months early1. In October 2023 it was reported that judges had been told not to jail rapists due to overcrowded prisons2. But rather than have a sensible debate about why the UK imprisons more of its citizens than any other country in Western Europe3, the Conservative government is pressing to incarcerate even more people and increase the prison population by another 20,000 over the next five years4. This is despite weighty evidence showing that putting more people in jail does nothing to cut crime. The core problem underneath all these statistics is the crisis of reoffending, the underlying issue I tackle in Time After Time, which is responsible for 80 per cent of all crimes. Contrary to popular feeling, we don’t have a growing number of criminals in this country, but we are plagued by a hardcore group of repeat offenders who are stuck inside a system that won’t let them out.

Stories of crime fill our social media feeds, news websites and streaming services, but the issue of reoffending rarely gets much oxygen. This is why, along with most authors, I was keenly watching the news cycle as my publication day approached in the hope of catching a story connected to my book to give me the opportunity to debate the subject and promote my wares. I therefore felt that all my Christmases had come at once when Daniel Khalife allegedly escaped from HMP Wandsworth on the very day that the hardback edition of Time After Time was published in September 2023. (I have to say ‘allegedly’ as he’s pleaded not guilty and will be going on trial soon, where I will be avidly watching from the press gallery with a large bucket of popcorn.)

The incident enabled me to do more press interviews than Tom Cruise on a film junket, and I got so much airtime that both Lewis Goodall and James O’Brien accused me of orchestrating the (alleged) escape to garner promotional coverage. For the record, I didn’t drive the suspect grocery truck out of Wandsworth, but I was nonetheless grateful for the opportunity to highlight the terrible state of the criminal justice system and how it makes reoffending all but inevitable.

Twenty-four hours later the debate returned to the fringes of political discourse, where it remains in the same tired rut. The public continually bemoan the stubbornly high levels of crime while simultaneously advocating the harshest possible punishments, which only exacerbate reoffending. This contradictory position is entrenched within both major political parties, which are engaged in an endless arms race on criminal justice. MPs line up to advocate for longer sentences while cutting prison budgets, which results in offenders being simply warehoused in archaic dungeons in appalling conditions until they are eventually released with zero support, perfectly primed to reoffend all over again.

2024 is an election year, and, unless Rishi Sunak receives some supernatural intervention, he is certain to lose the coming election. The transition to an incoming Labour government is the perfect moment to reset this broken debate and push for rational, evidence-based policies on criminal justice, rather than the hysterical, regressive and ineffective measures that have plagued the system for the last fourteen years. Democracy isn’t just about voting once every five years. If you are upset, depressed and made fearful by the contents of this book (I know I am) then we must do all we can to inform our political representatives that we have to move away from these broken Victorian ideas and finally adopt a twenty-first-century approach to crime and punishment.

Prologue

It’s March 2021 and I’m cycling home from the Old Bailey. I’ve been following an extremely convoluted manslaughter case that’s making my head spin, and I’m so distracted I take a wrong turn into Bedford Square. I stop to get my bearings and realise I’m right outside the flat of my former cellmate, Gavin. Two years previously, we’d both been released from HMP Spring Hill, and had initially stayed in regular contact. Ostensibly we met up to chew the fat and reminisce about old times, but under the surface we had formed a mutual support network to weather the emotional roller coaster of reintegrating with the outside world.

Inside jail, our lives were near identical – incarceration is reliably uniform and monotonous – but outside the prison walls we had increasingly fewer things in common. I had written a book about my time in HMP Wandsworth called A Bit of a Stretch, which was published in 2020 and thrust me back into the media spotlight. Meanwhile Gavin was struggling to make ends meet and support his wife and two young children. As our lives diverged, we had less to talk about and our meetings became more infrequent.

A year ago, the pandemic had stopped any socialising. Then my WhatsApp messages, which Gavin usually replied to with the promptness of an efficient drug dealer, were left hanging, with just one grey tick indicating that the missive hadn’t been received. Criminals often switch phones to avoid detection, and I just assumed Gavin hadn’t sent me his new number. Standing outside his place now, I feel a pang of guilt that I allowed our friendship to wilt, and worry that Gavin assumed I was shunning my former prison colleagues to avoid scuppering my public profile.

I lock up my bike and hit the bell for his flat. His wife, Precious, buzzes me through, and I walk down the side alley. Not for the first time, I marvel at the size of the apartment. Shortly after his release, Gavin engineered a council tenancy switch and now lives in this fantastic location for an enviably meagre rent. Precious opens their door slightly, trying to stop her two-year-old son, Noah, from scampering out.

‘Is Gavin around?’

‘He’s inside.’

Lazy bastard, I think. Probably having an afternoon snooze, something he frequently enjoyed when we were roommates. I slip into the flat and Noah hugs my leg happily. Precious is a formidable Nigerian woman in her late thirties who stood by Gavin while he was in prison and never lets him forget it. She motions me to the lounge, which has a large walk-in wardrobe that he built for his wife’s prodigious shoe collection. The TV is playing The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie too loud. I try to turn it down but can’t find the remote control.

Precious comes in looking febrile and closes the door.

‘Is he getting up?’ I ask.

‘He’s inside,’ she says again, unsmiling.

‘I know he likes an after-lunch kip, but can’t we give him a poke?’

‘He’s inside prison. They got him a year ago.’

I want the ground to swallow me up.

Introduction

Reoffending is the great hidden scandal of our times. The UK has among the worst recidivism rates in Europe, with 45 per cent of adult ex-prisoners reconvicted within one year of release. For people serving short sentences, this rises to a staggering 61 per cent.5 Given that large numbers of crimes are never even prosecuted,6 the real number of reoffences will be much higher. Reoffending costs the taxpayer about £18 billion a year,7 which is roughly a quarter of the education budget and more than half what we spend on defence.8 Reoffenders are responsible for the vast majority of all crimes: around 80 per cent of those receiving cautions or convictions have offended before.9 Turning this statistic on its head shows just how deep the problem runs. If we solved reoffending, we’d prevent 80 per cent of all crimes.

A key factor is the country’s hideously dysfunctional prisons, which I often compare to hospitals that make patients more ill or schools that lower pupils’ IQs. I should know; I spent two and a half years inside, having been convicted of tax fraud in 2016. There’s a lot of noise in the news about bad prisons, but there is another side of the reoffending coin that is rarely talked about. Ninety per cent of offenders are automatically released after serving only half their sentences; the rest is spent out in the community supposedly being rehabilitated by the probation service. The judge in my case handed me a five-year prison term, but I was released after 50 per cent of this, 911 days (yes, I counted every bloody one of them).

Probation is the catch-all term for the web of official bodies charged with supervising offenders for the rest of their sentence and ensuring they stay on the straight and narrow. By any measure this supervision is failing at a catastrophic level. The head of the parliamentary Justice Committee has stated that ‘Years of underfunding and botched reforms have left the probation system in a mess.’10 A National Audit report concluded that probation was ‘under siege’ and incapable of providing justice for ‘victims, offenders, taxpayers or society’.11A Bit of a Stretch showed that prisons are mired in dysfunctional chaos, but they are a paragon of competence compared to the probation service.

About 70 per cent of probation was privatised in 201412 by the hapless Chris Grayling when he was justice secretary; a man who would later waste millions on a ferry company that didn’t have any ships.13 The supervision of low- and medium-risk offenders was handed over to community rehabilitation companies (CRCs), whose primary interest was profit, and staff numbers were slashed.14 High-risk offenders were looked after by the government-managed National Probation Service (NPS), which suffered huge budget cuts.15 Meanwhile the number of people under supervision had shot up, nearly doubling between 2015 and 2020.16 The number of offenders returning to prison for breaching their licence rose by 47 per cent in three years, while the proportion of supervised offenders recalled to custody on short sentences increased twelvefold, from 3 per cent to 36 per cent.17

By 2019, the writing was on the wall. A landmark report called Grayling’s reforms an ‘unmitigated disaster’.18 The National Audit Office concluded that privatisation had wasted almost £500 million, and said the government had ‘set itself up to fail’ by using ‘ineffective’ contracts with private firms which were woefully incapable of monitoring criminals in the community.19 All CRC contracts were terminated and probation was renationalised once more. But the damage to the system is now entrenched, and it will take years and significant additional funding to recover.

If you’re wondering what this has got to do with you, the collapse of the probation service has led to a surge in reoffending and far more victims of crime. The number of rapes, murders and other serious crimes committed by offenders on parole has risen by more than 50 per cent since Grayling’s reforms.20 A 2017 Inspectorate of Probation report found that ‘The quality of CRC work to protect the public is generally poor, and poor work by the CRC to protect against the risk of harm left victims vulnerable.’21

It’s not hard to see how poor supervision leads to recidivism, as every three days someone is murdered by an offender on license.22 In June 2022, Jordan McSweeney raped and murdered Zara Aleena in east London only nine days after he got out of prison. He had served nine prison terms for burglary and weapon offences and had a long history of violence towards women. He was only allocated a probation officer a week before his release and was wrongly assessed as medium risk. He missed his first probation appointments but wasn’t recalled to prison because his probation officer was struggling under a 50 per cent higher workload brought on by chronic staff shortages. The Chief Inspector of Probation’s report was scathing: ‘The Probation Service failed … He was free to commit this most heinous crime on an innocent young woman.’23

There is also a terrible human cost to offenders themselves. Every two days an ex-prisoner takes their own life while under probation supervision, a sixfold increase in the last ten years.24 I know several offenders who have found the outside world so difficult that they’ve deliberately reoffended just so they can return to prison, which is an astonishing indictment of the services that are supposed to be supporting offenders in the community.

In the months after my release, I kept hearing of former colleagues returning to jail. I found this extremely depressing and grimly fascinating. These guys knew exactly how bad conditions were on the inside, and yet still they’d gone back to square one. The drumbeat of another ex-con reoffending sent the same intractable question round and round my head: if British prisons are so awful, what’s going wrong in the outside world that means so many people keep going back?

This book is my attempt to find an answer. I’m in a strangely unique position to do this, as I’m both an investigative journalist and a former convict. Ex-jailbirds are a naturally cagey bunch who are understandably hesitant to discuss their activities, but my own lengthy imprisonment inadvertently ingratiated me into this normally elusive community. A criminal record is usually a barrier to employment, but for this particular job it’s an absolute necessity, allowing me to reach parts of the criminal underworld others can’t get near. A Bit of a Stretch explored life behind bars, while this book looks at the other side of the coin to see why ex-prisoners can’t go straight.

Writers often meet their subjects for a couple of hours, but I’ve been able to track these repeat offenders over several years. I shared a wing with some of them in Wandsworth back in 2016, and I’ve followed their ups and downs ever since. My friend Ed has been inside five times since I’ve known him, though this will probably have increased by the time the book is published. They are deeply flawed, chaotic and damaged characters, but also warm, funny, intelligent and kind. It’s fair to say they are largely rubbish at their chosen profession, given how often they get caught. Their crimes range from shoplifting to murder. Only one of them, in my view, is irredeemable.

I’ve also spent months digging into the official bodies, charities and companies that are supposed to prevent reoffending, and have uncovered shocking failings that are published here for the first time. This includes an investigation into the biggest mass shooting in the UK for ten years, exposing serious flaws in the supervision of the perpetrator that the police would rather you didn’t know.

What started as a simple quest to track persistent offenders has grown into something much bigger. Story after story has presented me with the same dark conclusion: that the system doesn’t really want people to go straight. This isn’t deliberate, but justice apparatus has nonetheless developed an inescapable gravitational pull, relentlessly sucking people back to prison despite their best efforts to escape. The criminal justice system has morphed into a dark monster that grabs people with its tentacles and refuses to let them go. The problem goes way beyond reoffending, as you can be reimprisoned without committing any more crimes. One of my contributors was incarcerated indefinitely for simply attending a party, despite not even turning up. Another went on trial for a violent assault that he had been convicted and punished for 18 years before. We’ve inadvertently developed a merciless system that arbitrarily decides that certain people are utterly beyond redemption and tries to lock them up for the rest of their lives.

Like A Bit of a Stretch, there is plenty of black comedy in these pages. Simon successfully escaped a high-security prison by pretending to be his twin brother. Alex spent nine months living in luxury hotels masquerading as the 12th Duke of Marlborough, despite being 25 years too young. And Ed was banged up for several months as his probation officer didn’t like his rapping.

I’ve also interviewed the victims of some of these offenders about how their perpetrators have been punished, as well as speaking to leading academics, lawyers, the former head of the Parole Board, ex-probation officers, politicians and forensic psychologists to try to understand why Britain is addicted to endless imprisonment.

Each chapter is based around a central character who illuminates wider problems in the system, such as accommodation, drugs and mental health. I’ve mostly used real names but had to deploy a few pseudonyms so that I don’t get certain people sent right back to jail, as they’re perfectly good at doing that themselves. Fake names have been put in quotation marks in the chapter headings, and I’ve changed a few personal details to confuse any armchair detectives. Some of the stories overlap in time and aren’t told in chronological order. Many contributors allowed me to tape our conversations so I could write our exchanges verbatim. Though if any police officers are reading this, I’ve now destroyed these recordings, so please don’t bother kicking my door in.

1

‘Gavin’

‘The needle returns to the start of the song and we all sing along like before.’

I met Gavin in early 2017 at HMP Ford. This was the open prison I moved to after my nine long months in Wandsworth, and the conditions initially felt like paradise in comparison. While Wandsworth fitted every cliché of a scary high-security Victorian jail, Ford, on the site of an old RAF base near Brighton, is often compared to a shit Butlin’s. It’s mostly comprised of wooden huts and Portakabins, and inmates are free to roam around the grounds. I found the food infinitely better and I could exercise as much as I wanted, but the best part was the family visits. We had two-hour slots, rather than the meagre hour at Wandsworth, and the visiting area was like an airport waiting lounge. There were only two officers present, who sat back and let us get on with it. Some of my colleagues took the opportunity to physically reconnect with their wives and girlfriends. I was finally able to play properly with my son, Kit. He was four when I was convicted, and the separation had been pretty traumatising for both of us. The new relaxed environment massively helped us rekindle our relationship, and Kit stopped feeling his dad was in prison.

On the downside, my new home put a much greater strain on Kit’s mother, Lottie. We’d separated before my imprisonment but remained good friends, and she’d brought Kit to Wandsworth regularly, as she lived in London. But Ford was three hours away and it was impossible for her to travel every week, so I was now destined to see my son less frequently. The only glimmer of hope was that I could soon meet them outside the prison, when I qualified for day release. Open prisons are essentially resettlement centres designed to ease offenders back into the community and help them reintegrate into the outside world.

Day in day out

The technical term for day release is Release on Temporary Licence (ROTL). It allows low-risk prisoners out of the prison grounds for a few hours to work, study, do community service and visit their families, all of which helps reduce reoffending.25 ROTL is only available to offenders at open prisons, which is about 5 per cent of the total prison population,26 so it’s not used nearly as much as it should be. It’s especially important for long-serving inmates, who would otherwise be dumped onto the streets completely incapable of handling the outside world.

Like everything else in the prison system, ROTL is needlessly complicated and bureaucratic. Inmates are only eligible after they are 50 per cent of the way through their time in custody, which for me was 15 months, and there’s a series of tortuous administrative hurdles to jump over to get the green light. Discretion of ROTL is ultimately up to individual governors, and some are far more risk-averse than others. Every year a handful of crimes are committed by prisoners on ROTL, which always triggers bad headlines and official panic, leading to knee-jerk restrictions to the service.

My ROTL eligibility date was in October 2017. I’d assumed Ford would allow me to travel to London a couple of times a month to visit Kit. In addition, I’d started an Open University degree at Wandsworth, which I’d hoped I could transfer to a nearby college. But I soon discovered that all this was a pipe dream. Ford had become a dumping ground for prisoners who were completely unsuited to open conditions, and the governor was strongly opposed to letting any of us out of the gates. Out of 700 residents, only a dozen were actually working out on ROTL.

I was pretty depressed by this setback, but soon picked myself up and looked for ways to improve my lot. Prisoners love gossiping about other prisons, and there’s a thriving TripAdvisor-style network of jail reviews. I kept hearing glowing reports about HMP Spring Hill in Oxfordshire. The grapevine indicated that the governor had a much more progressive attitude to ROTL, and it was significantly closer to London, so I’d see more of my son. I requested an immediate transfer. My supervising officer, however, didn’t sound very hopeful.

‘Doubt you’ll go any time soon, unless there’s a few of you on the list.’

Over the next fortnight, I basically became a cheerleader for Spring Hill, and went round the camp trying to convince other prisoners to escape the drudgery of Ford. My efforts fell on stony ground, until eventually I crossed paths with a middle-aged drug dealer called Gavin. He was in his late forties and looked like a cross between Father Christmas and Danny the dealer in Withnail & I, right down to his flattened R’s. He had an unflappable sardonic manner that was in stark contrast to the hyperactive youths who permeated the prison.

‘Gotta get out of here,’ he told me. ‘The missus doesn’t drive so I never see my family. My daughter visited every week at Pentonville, now I’m fucked.’

We agreed to join forces and I typed him out a transfer request. With only two of us on the list, I didn’t hold my breath, but a week later a senior officer ambled into my room. This caused a bit of a stir, as the other residents in my hut thought we were being raided and hurled their mobile phones and drugs out the window.

‘Bad news is there won’t be a transfer van to Spring Hill until December,’ the officer said with a wink. ‘Good news is I fancy a day trip, so I’ll drive you and Gavin tomorrow. Get your shit together for nine a.m. sharp.’ Once he’d left, I apologised profusely to my neighbours for their lost merchandise.

The next morning, Gavin and I mustered at reception. We were giddy with excitement, like two kids going on a school trip to Alton Towers, even though I was bracing myself for the journey. I’d previously endured several trips in prison vans, the horrible sweat boxes that you see on the news, which have no leg room or seat belts and bash you about like a battery hen. We were thrilled, therefore, to see the officer pull up in a gleaming minibus, which is the penal equivalent of taking a Learjet. We spent the whole journey gawking out at the green fields, luxuriating in the cushioned seats and swapping war stories from our time inside. We’d both had to endure mental cellmates and agreed to bunk together if we could wangle it.

Not far from Bicester, the van drove through the tiny village of Grendon Underwood and into the grounds of HMP Spring Hill. I later learned that during the Second World War, the site was the headquarters of MI6. In the centre is a large, imposing manor house, encircled by a dozen dilapidated wooden shacks. We were processed by the reception officers, which always takes ages, as the poor screws have to register the make and colour of every single item of clothing. Mercifully there was a spare double room in the induction hut, where new prisoners live while they settle in, and Gavin and I snapped it up.

I almost destroyed our relationship within hours of moving in. We’d arrived on 8 June 2017, which happened to be the day of the general election. I’ve always been obsessed with politics and have followed every election since I was a kid.

‘Are you up for watching the election coverage?’ I asked him.

‘Nah, shower of cunts chatting shit, innit. When’s it finish?’

‘Er, well, it usually goes right through till morning. Though in 2010 there was a hung parliament and it went on for days.’

‘Are you fucking mental!?’

TV viewing is the primary source of domestic strife between cellmates. Watching telly in the small hours is a massive red flag, as it’s textbook behaviour of schizophrenics who want to block out the voices. Gavin looked as if he thought he’d made a colossal mistake sharing a room with me, so I hurriedly explained that this was a one-off request and he could dictate the TV schedule for the next fortnight. It’s a testament to his good nature that he grudgingly agreed.

‘If Corbyn wins, you can suffocate me with this pillow,’ he grunted as he turned in for the night.

I turned the volume right down and watched agog as Theresa May lost her majority. I kept tiptoeing to the prison phone at the end of the hall to call friends about the latest developments. Each time I’d pass the recreation room, which was full of prisoners glued to the results on TV, although they were all watching Love Island rather than the election.

Despite this rocky start, Gavin and I got on famously. We watched each other’s backs, shared intel about how the prison ran, and talked for hours about our families back home. I liked him a lot but craved my own personal space. The prison did have a number of single cells, but there was a six-month waiting list. The only other option was the dozen highly sought-after study rooms for inmates doing OU courses. I put in a request saying I was falling badly behind with my psychology studies. In August, I was successful and took up residence in a room on the ‘Browns’, one of the most desirable huts in the prison. My study room had an internet-disabled PC and an en suite shower, as well as my own loo and sink. It was the first time I’d had a room to myself since I was incarcerated, and it was like staying in the Ritz.

An unexpected consequence of living alone was that I became a bit of a recluse. Wandsworth was a miserable shithole on every level, but the terrible living conditions and daily drama meant I formed extremely strong bonds with my cellmates and neighbours. There was always something crazy to gossip about. In Spring Hill, however, the biggest weekly news was the servery running out of chips. This relative boredom led to lower blood pressure, but I soon became pretty introverted. I’d go for days without having a conversation longer than a couple of words, which didn’t do wonders for my mental health. Previously I’d chatted away with my cellmate about the highs and lows of the prison experience, but living alone meant everything remained bottled up inside. I was still coming to terms with my imprisonment; its impact on my life and my relationship with my son. Sharing a cell had been crucially important to coping with the crisis, and being stuck with my own thoughts allowed negative feelings to fester without a safe outlet. Despite the calmer environment, I had the darkest moments of my sentence at Spring Hill.

Gavin was the only person who noticed. I’m not sure if it was by luck or design, but whenever I was really struggling mentally, he’d stick his big hairy head round my door and grunt, ‘All right, you daft bastard, let’s have a walk.’ We’d stroll around the large field behind the accommodation huts, from the far corner of which we couldn’t see any prison buildings. It was as close to freedom as we could get. There were often lively games of football going on, and the ball would sometimes fly off the pitch in my direction. I’d always screw up booting it back, and Gavin would crease up, shouting, ‘You kick like a fucking girl.’

These aimless strolls boosted my mood immeasurably. They also helped me get to know Gavin better as he opened up about his earlier life. ‘I used to be a right mental cunt. Was in a Chelsea football firm in the eighties, trashed every pub on the King’s Road.’ He’d sold cocaine for years and did a roaring trade at the Evening Standard offices. ‘The journos had to be up all night writing the morning edition, so I’d drop in and dole out the powder.’ He’d had no qualms about getting high on his own supply, but that had changed eight years previously, when he’d nearly died in a fight. ‘Fucking wake-up call. Went through NA, the whole Twelve Steps. Tough gig, but haven’t touched a drop or sniff since.’ Despite being completely clean, he’d carried on dealing, unable to wean himself off the quick money and easy lifestyle. ‘Not good for anything else, am I?’ he muttered on several occasions.

I didn’t think this was true. Gavin was a smart guy and the only person keeping me sane over that long summer. He was a big fan of antiques and would often guess the correct values on Cash in the Attic. He’d set up several successful antiques businesses, though these inevitably became a front for drug money. There had been a few arrests, but he’d always slipped through the net. ‘Thought I led a charmed life, but I was just banking the pain for later.’

Gavin was sucked into the ‘hot hand’ fallacy, in which his past luck convinced him to underestimate his future risk. A few days after his daughter was born, he embarked on a caper worthy of a Guy Ritchie film. He travelled to Holland with several associates, where they wrapped 350 kilos of high-grade cannabis into a bunch of carpet rolls. ‘It was like fucking Cleopatra.’ They drove the van back to the UK, and were immediately busted by Waltham Forest CID. A search of Gavin’s home found £10,000 in cash and 60 grams of cocaine. He pleaded guilty straight away to get a discount off his sentence.

‘I got nailed with nearly half a ton of puff, but it was the sixty g’s of coke that fucked me.’ The cocaine tested 92 per cent pure, which was very popular with Gavin’s clients but less so with the judge. ‘The beak said I must be really close to the source and gave me another six months. They’d be happier if I cut the gear with salt, but I get whacked for having a quality product.’ He was handed six years and sent to HMP Pentonville, one of the few prisons that can claim to be worse than Wandsworth.

Gavin could stomach the foul conditions but was heartbroken by the separation from his baby daughter. ‘The missus would bring her in and the screws would search the cot. It was the worst thing I’d ever seen.’

We talked a lot that summer as we crossed off the days to our ROTL eligibility dates. I successfully applied to finish my degree at Oxford Brookes, and from October 2017 I was allowed out to study five days a week. This was an absolute godsend, and for the final 15 months of my sentence I spent most of my waking hours outside the prison gates (I’ll talk more about this surreal experience in the next chapter). Gavin got a job at Pret A Manger, which was actively recruiting serving prisoners to replace the workers who’d left the UK after Brexit. He spent the next year making coffee at the John Radcliffe Hospital, where his jovial manner made him a big hit with patients and staff alike. I’d often visit to laugh at his dainty Pret uniform, complete with tiny paper hat.

‘Fuck off and do your dissertation,’ he’d bark as he craftily slipped me a free cappuccino.

The real joy of ROTL was being able to see our kids in London. This started off as day trips, but in the last nine months we were rewarded with the luxury of home leave – five days and four nights where we could stay at home. We’d share a taxi to Bicester and get the train to Marylebone. ‘Can’t wait to see Miley and bump uglies with the missus,’ Gavin would beam as he disembarked. He didn’t mess about, and after a few months he proudly informed me that Precious was ‘up the duff’. This wasn’t an accident. Precious had only agreed to stick around if she could have another child at the earliest opportunity.

I’ve since met several ‘home leave babies’, conceived while their dads were still in custody. My friend Max was transferred to Spring Hill from another prison by his wife, and they took a quick break in an A4 lay-by.

‘Who says romance is dead?’ I told him.

‘She wanted to do it in a Travelodge,’ he complained. ‘But I wouldn’t have had time to buy new trainers.’

I was released a couple of months before Gavin, on 28 December 2018. Before I could leave, I had to attend a resettlement interview to help me ‘forge meaningful goals and make the right life choices’.

‘What work, if any, are you expecting to undertake once released?’ the support worker asked officiously.

‘Er, film director,’ I said, trying not to sound like a complete dick.

She rolled her eyes so far they disappeared into the back of her head. ‘And in the real world?’

An officer I knew leaned over to her, smirking. ‘He actually is a film director. Got done for funding a documentary with bent tax money. It’s quite good.’

‘That’s not on my drop-down menu,’ she huffed back.

I was handed a release grant of £47.50, which was supposed to cover food and accommodation on the first night. A quick google later revealed that a room at the nearest B&B cost £62. I then signed my licence, a three-page document spelling out the conditions of my release, which would apply for the next two and a half years. These included not reoffending, attending all probation appointments on time, and avoiding any ‘bad behaviour’, which seemed a bit too broad for comfort. Any breaches could trigger a recall, which would send me right back to prison, potentially for the full remainder of my sentence.

That afternoon I had my first meeting with my probation officer in London. The journey was pretty nerve-racking, as I was terrified of being late and being bounced back to jail. When my friend David was released, the officers took so long processing him that he didn’t get out until after the time of his probation appointment. He had to endure a terrifying phone call with an unsympathetic probation officer, desperately pleading with her not to reimprison him for failure to attend.

I arrived early at the Islington offices of London CRC (Community Rehabilitation Company), the private company then responsible for supervision of low-risk offenders. I had religiously abstained from celebratory alcohol in case anyone smelled my breath. I needn’t have bothered. I was the only offender in the waiting room who wasn’t openly drinking booze.

I sat there for an hour, getting increasingly panicked that something had gone wrong. A harried probation officer called Dan eventually came out.

‘No one told me you were coming,’ he muttered. ‘Who are you again?’

I introduced myself, and he asked me a bunch of questions about my crime and my current situation.

‘I’ll be your probation officer for your whole time on licence,’ he said sternly. ‘Consistency of contact is important for rehabilitation, and we’ll need to develop a bond of trust.’

I said goodbye and then never heard from him again, as my file was immediately passed on to a series of equally clueless officials.

I’d spent the previous 30 months dreaming of this day, but I found the process of leaving prison painfully destabilising. I was obviously thrilled to finally taste freedom but also deeply apprehensive about the future. For the previous two and a half years I hadn’t had to worry about bills, finding work or providing for my son. Now I had to think about all the boring challenges of the real world. Some of my contemporaries tried to make up for lost time and immediately went on a massive bender. I went the other way and shunned social contact wherever possible. I loved seeing my close friends again, but I hated meeting people in groups larger than about six. I found it weird trying to be the same person as before, like wearing an old suit that didn’t fit. It was hard engaging on the same level again, as if I was tuning an old FM radio and not quite finding a clear signal. Everyone was really kind and supportive, but nobody understood what I’d been through.

All this destabilisation made me crave the company of people who’d had the same experience, and so I was pretty relieved when Gavin was released a couple of months later, in the spring of 2019. I’d regularly bike down to his flat for a natter, reprising our relaxing chats at Spring Hill. We’d moved through our sentences in lockstep, and it now felt like we were two demobbed soldiers who’d survived a long war. Precious soon gave birth to a baby boy, Noah, and it looked like they were living the dream. Miley rarely left her father’s side, and more than once she told her dad to never go away again.

Gavin had also been released at half-time under the same licence conditions as me. I realised he wasn’t being fully compliant when he pulled up in a gleaming Audi.

‘Just got her back off the old bill,’ he said proudly. The police had seized the car to settle his proceeds of crime confiscation order. This meant he was carless when he was released, which had become a real struggle with two young children. So he’d solved the problem the only way he knew how.

‘How did you pay them off?’ I asked, already knowing the answer.

‘Back in the game, aren’t I,’ he admitted coyly.

‘You’ve been selling drugs to raise the cash to reclaim a car that had previously been impounded for selling drugs?’ I couldn’t keep the disappointed tone out of my voice.

‘What the fuck else am I supposed to do?’ he countered sharply. ‘Not gonna make twenty large from serving lattes, am I? Not all of us can write a book.’

He had a point. I wasn’t in any place to judge, as my fortunes had turned out rather well since release. Apart from my book deal, I’d had several offers of film work, the media industry having been surprisingly forgiving of my past. Gavin had a family to support but no qualifications or legitimate connections to fall back on. For me, criminality had been a blip in an otherwise law-abiding life, whereas offenders like Gavin had a vastly higher hill to climb. Dealing drugs had been ingrained as a survival mechanism, and he found it impossible to extract himself from the life he knew.

Soon after the pandemic hit in 2020, he stopped responding to my messages. I suspected he hadn’t sent me his new mobile number as our paths were clearly diverging and we had less and less in common. Like so many other prison friends, he just slipped off my radar, until March 2021, when I found myself standing in his sitting room while his devasted partner explained that he was back in jail.

Precious speaks in a low whisper so the kids don’t overhear. Nonetheless, Miley knows I’m her dad’s friend from prison and keeps sticking her head round the door. Her interruptions are really upsetting as I start to process that she’s just lost her father again. It’s like seeing a flashback to Kit when I was first imprisoned. I’m furious with Gavin for going right back to the start, and somewhat egotistically, I see it as a betrayal of our friendship.

‘Does Miley know where he is?’ I whisper to Precious after she shoos her daughter away.

She bites her lip. ‘I’ve lied. Said Daddy is away on business in Africa.’

‘Is she buying it?’

She shakes her head slowly. ‘Miley’s a smart girl. Not like her dad.’

Gavin was imprisoned at the start of the first COVID lockdown, so they haven’t seen him in person for over a year. His only contact with his family has been by phone, and Miley often gets overwhelmed and has to hang up.

Locked up in lockdown

The prison system was woefully ill prepared when coronavirus struck in March 2020. All visits were cancelled, and prisoners were confined to their cells and only allowed out for food. Under public pressure, the government sensibly promised to release up to 4,000 low-risk prisoners a few weeks early on home curfew (in England and Wales), to create space for more effective quarantining,27 as well as 70 pregnant women at high risk from the virus.28 But the process was completely bungled, with only 175 of the 4,000 eligible prisoners being released,29 and only 21 pregnant women.30 The Chief Inspector of Prisons noted ‘the decline in prisoners’ emotional, psychological and physical well-being. They were chronically bored and exhausted by spending hours locked in their cells … Some said they were using unhealthy coping strategies, including self-harm and drugs … They frequently compared themselves to caged animals.’31 The only reason the system didn’t completely collapse was thanks to the bravery and dedication of thousands of prison officers, who carried on working in breeding grounds for the virus. Many sadly lost their lives. This had a horrific impact on staff mental health, and a Ministry of Justice official admitted to me that the number of officer suicides spiked during the pandemic.

I tell Precious I’ll help as much as I can and ask for Gavin’s prison number so I can get in touch. She writes it on a piece of paper with Miley’s drawing of a horse on the other side.

‘Please talk to him,’ she pleads. ‘He should do something proper inside. You wrote that book, made you money when you got out. He should take a course, go straight this time.’ I nod in agreement, and don’t mention that the pandemic has destroyed what little prison education there was.

Precious admits that money is really tight. Gavin’s associates had promised to drop round cash, but she hasn’t seen them for months.

‘Do you want to say goodbye to Miley?’ she asks. I lie and say I have to run. If I see her again, I’ll completely lose it.

I write to Gavin at HMP Wayland, and a few weeks later I get a call.

‘What’s up, dickhead?’ grunts a familiar voice.

‘Gavin! You liked prison so much you had to go back? I hope you’re getting loyalty points.’

‘Fuck off.’

‘What happened this time?’

‘I was only caught with a few grand cash.’

‘Was it your money?’

‘Course it wasn’t. I wish it was my money. I’m just the delivery driver,’ he adds a bit too firmly.

‘Hey, I’m not on the jury.’

We both know this call is being recorded, and I guess that Gavin is downplaying his role for the benefit of the tape. Many a careless inmate has been hit with new charges because of loose words on a prison phone.

‘So why did you get such a long sentence?’ I ask carefully.

‘I had one of them cryptic mobiles that’ve been all over the news.’

Gavin was caught with an EncroChat encrypted phone, highly popular with wholesale drug dealers and organised crime groups, who believed the devices were an impenetrable means of communication. But French law enforcement secretly hacked the servers, which was the equivalent of breaking the Enigma code, and passed on vast quantities of intelligence to the UK’s National Crime Agency.32 The NCA swooped on hundreds of suspects, with Gavin one of the first to be picked up. He was arrested while he was still on licence and immediately recalled to prison for breaching his conditions. This is different from being remanded before trial, as remand prisoners get their pre-trial custody time deducted from their final sentence. Recalled offenders don’t get any deductions; it’s just dead time.

‘You must have been desperate to be sentenced,’ I say sympathetically, ‘just to start the clock.’

‘Tell me about it. Me and the other driver went guilty straight away, but we were tied to a third guy who said he had nothing to do with it. He fought it all the way, so we sweated for months waiting for court.’

‘Sounds like prisoner’s dilemma on steroids.’

Breaking a sweat

Prisoner’s dilemma is a thought experiment coined by the American mathematician Albert W. Tucker. Two criminals are arrested for committing a robbery together and put in separate cells. Each knows that if they both stay silent they will get a lesser punishment but if one rats the other out then he’ll walk free and the remaining criminal will serve the full sentence. It’s used in economics to illustrate how two individuals acting out of self-interest might not produce an optimal outcome. I had the opportunity to see it unfold in real time as co-defendants were imprisoned on remand and had to decide whether to trust their associates or cop a plea. I even orchestrated a game of prisoner’s dilemma with actual prisoners one bored afternoon at Spring Hill, which led to some very colourful language when it was suggested people would improve their chances by grassing on their mates.

Gavin sensibly pleaded guilty early to get a reduced sentence, but still served extra time as his co-defendant wanted to beat the case and dragged out proceedings.

‘That cunt cost me another year, but he paid up when it got to court. Prick got found guilty, judge said he was leading role and gave him a nine. I squeaked a five, was quite happy with it,’ he says cheerfully.

‘How’s it been inside?’

‘You won’t believe this, but I’ve seen loads of people we knew at Spring Hill who’re back inside.’

Sadly, I can believe this. ‘How are things with Precious and the kids?’

‘Haven’t seen them once in sixteen months,’ he says emotionally. ‘Miley broke my heart on the phone the other day. She said, “Daddy, can I just ask you a serious question? Are me and you only going to have a daddy–daughter relationship on the telephone? Are we ever gonna see you again?” Oh mate, I just burst into tears. I’ve seen loads of bad things in my life, people bashed up, stabbed, doesn’t bother me. Then someone so little says something like that and I’m destroyed.’

When I was in Wandsworth, I worked as a prison Listener – a volunteer trained by the Samaritans to console inmates who are suicidal or depressed. Chatting to Gavin, I feel I’m reprising my old role, desperately trying to raise his spirits with crumbs of comfort. ‘Well, a five isn’t the end of the world. It’s what I got. You should get to open prison soon, sort your ROTL and see the kids at home.’

‘Working on it, mate. Got my Cat D* review in a month, so I’m doing whatever I can to look good. Even signed up to be a Listener.’

I can’t help but laugh at how he’s following in my footsteps. ‘You’ll knock it out the park, mate. You were basically my personal therapist at Spring Hill.’

‘How are you doing these days?’ he asks. I find this a tricky question when talking to serving prisoners, as I don’t want to rub salt in the wound by enjoying my freedom too much.

‘Not too bad. I’m writing a new book.’

‘What’s it about?’

‘Well, er, it’s basically about you, my friend. I’m asking why so many people end up going back inside.’

‘What’s my cut?’

‘How about I drop down some cash to Precious?’

‘You’re a gent and a scholar, Chris. Gotta go, something mental’s going on.’ I can hear muffled screaming in the background as he hangs up.

A few days later, I visit Precious again. She waves me in and orders me to take my shoes off, sternly pointing out that I forgot last time. Noah hands me a small plastic car and coughs loudly.

‘He’s been ill,’ says Precious, leaning against the wall. She looks exhausted. ‘Had to go to hospital, kept him in for two nights.’

I tell her about my call with Gavin. She seems pleased that I’m taking an interest.

‘Is he gonna do something clever inside?’

‘Well, he’s training to be a Listener.’

She barks out a loud laugh. ‘Gavin? A Listener? He never listened to me once in his bloody life. What does it pay?’

‘Um, nothing. It’s purely voluntary. But it will help him get his Cat D and move to open prison sooner.’

‘Better than nothing. His problem is self-esteem. He thinks he’s good for nothing else so just goes back into drugs. It’s killing me.’

Noah gives me another toy and gurgles happily. I pick him up and he throws his arms around me. ‘You’re heavier than last time,’ I say. ‘Getting really big.’

‘And Gavin’s missing all of it,’ Precious says bleakly. ‘Boy doesn’t know who his dad is.’

‘How are you coping?’

‘I’m not. Can’t run the house with two kids. Might go to Holland and stay with family. It’s too difficult here.’

This will take the children even further from their father, but I can’t advise her against it as she’s clearly hanging by a thread. Kit’s mother, Lottie, had a great support network while I was away; her family lived close by and regularly helped with childcare. Precious doesn’t have anyone nearby in London, and Gavin’s former associates have all vanished.

A few months later, in October 2021, Gavin calls me in a buoyant mood.

‘What you up to?’ he asks.

‘Been out filming.’

‘What, more gay porn?’

‘That joke never gets old.’

‘Got my Cat D stamped,’ he announces proudly. ‘Just need to get a bus to an open nick. But the bloody vaccinations are a kicker; won’t get shipped without a shot.’

‘Vaccines are available in all prisons now, I saw it on the news. Haven’t they offered you one?’

There’s an uncomfortable pause. ‘Refused it, mate,’ he says uneasily.

‘Why?’

‘Personal choice. Some people have, some haven’t. I had COVID already, when I was in Scrubs.’

‘Yeah, but that won’t protect you against Omicron, it’s reinfecting people all over the place. Listen, Gavin, if you ever take one piece of advice from me, get the fucking jab. You’re living in a COVID incubator.’

‘I don’t know what to think, mate,’ he says doubtfully. ‘My niece is double jabbed and she just tested positive. But then my sister hasn’t had any jabs and she’s tested negative. And they live in the same house.’

He who hesitates

Anti-vax sentiment was rife in prisons, where the vaccination rates for inmates and staff lagged well behind the rest of the population. In August 2021, it was reported that only 56 per cent of prisoners had received both doses, compared to 75 per cent of the general population, and the refusal rate was estimated at 40 per cent. This was fuelled by an inherent mistrust of the state, and bizarre myths claiming that the vaccination turned you gay, that your arm would drop off, or that the jab contained a tracking device.33

I try to coerce him towards enlightenment. ‘Tell me something, mate, do you wear a seat belt when you drive?’

‘I knew you’d come out with some clever bollocks like that,’ he says tersely. ‘I ain’t got COVID so why do I need a jab?’

‘So why do you wear a seat belt if you aren’t going to crash?’

‘But no one knows how the vaccine works, do they?’

‘They really do. It would be a shame if you died of COVID after surviving two prison sentences. I think your poor kids have suffered enough.’

Gavin bristles defensively. ‘My sister works in a bank. They have long days and aren’t allowed to use mobiles at work, so she barely sees her kids either. Soldiers have to go on tours overseas, don’t see their kids for ages. It’s not that different.’ I can feel him getting angry, so I quickly end the call.

Gavin gets shipped out over Christmas and ends up back at Spring Hill. In the new year, he calls me asking for a favour. ‘Have you still got your motor?’

‘Hasn’t been impounded yet. Do you need me to pick up some “cash”?’

‘Don’t be a fucker. I need to get approved for day release so I can go home and see the kids. The screw in charge of ROTL is a right bastard, says I’m a habitual offender and need extra scrutiny.’

‘He might have a point.’

‘He said I can only get ROTL to London if I do a local town visit first, but I ain’t got anyone to drive me.’

‘And you think they’ll let me do it?’

Gavin has already made the necessary enquiries, and the authorities are comfortable with me taking him out for lunch. So a month later, I put the postcode for Spring Hill into my sat nav and drive back to my old home. I bring along my new dog, Cookie, assuming that Gavin hasn’t had much interaction with animals apart from the rats in his cell.

As I pull into the car park, he is already lumbering over.

‘Taxi for Gavin?’ I call out in a cod-cockney accent. ‘You’d better not be sick in my cab.’

‘You’re not getting a fucking tip,’ he shoots back, as Cookie leaps out and jumps all over him.

I wait until we’re well clear of the prison grounds before I ask the obvious question. ‘So … were you really just the driver?’

‘Piss off,’ he admonishes.

I park up in Bicester town centre and buy us fish and chips. Gavin savours every mouthful as though he’s dining at Le Gavroche. ‘Best fucking meal I’ve had in years,’ he says as he mops up the grease.

‘I expect you’ll be serving up coffee for nurses again soon?’

‘It’s Greggs this time, mate. They’ve already said they’ll give me a job when I’m allowed to work out. Going up in the world, aren’t I?’

‘How is it with the kids?’ I ask.

‘Fucking terrible. Miley doesn’t buy it that I’m in Africa. Thinks I’ve been kidnapped. Started putting up signs round the neighbourhood saying, “Have you seen my daddy?” Then Precious says she’s thinking of leaving me.’

I want to twist the knife and tell him he shouldn’t have bloody reoffended. I want to point out that in the last two years I’ve seen his kids more than he has. I want to say that if only he’d asked me, I’d have helped him find legitimate work. But looking at him fighting back tears about what he’s done to his kids and his wife, I realise there’s nothing I can say that will make him feel worse than he already does.

I’m aware that the clock is ticking. If I don’t return him to Spring Hill in time, the police will be alerted and I’ll be arrested for harbouring an escaped convict. As we set off back to our old home, Spotify randomly chooses ‘Nothing Ever Happens’ by Del Amitri. The lyrics are eerily apt: ‘The needle returns to the start of the song and we all sing along like before’.

We pull up in the car park and I get out to say goodbye. On one of the lamp posts is a sign for a planning consultation. Someone’s proposing a large development in the field where we used to take our afternoon walks.

‘Strange place to build a new estate,’ I say.

‘Not exactly quality housing, mate.’

I peer closer and see that the plans are for a new super prison for 1,500 inmates.

If you build it they will come

The government plans to create 20,000 new prison places (on top of the existing 85,000),34 in stark acceptance that the reoffending crisis will get steadily worse. While the budget for probation has been steadily slashed, the government has instead found money to lock up even more people. Building these new jails will cost about £4 billion, far more than it would cost to effectively supervise and support offenders in the community. As of 2020, England and Wales imprisoned 138 people per 100,000 of the population, by far the largest number in western Europe. France clocks in at 105, Ireland at 81 and Norway at 59.35 Criminologists often hail the Scandinavian model of criminal justice, which uses education and retraining instead of brutal punishment. Rather than copy these effective techniques, however, the UK has long chosen to ape the policies of the USA, which incarcerates a whopping 810 people per 100,00036 and also has sky-high levels of reoffending. Locking more people up doesn’t actually help – according to the National Audit Office, there is no link between the prison population and levels of crime.37