15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

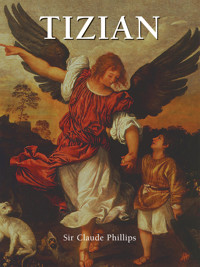

Not only does Sir Claude Phillips offer the reader a studied and insightful loook into the work of one of the world's most cherished painters, but he also invites us to discover the bustling world on the Venetian art circle in which Titian lived and worked. From his early years in the workshop of Giovanni Bellini, to his meeting with Michelangelo and his rivalry with Pordenone, the story of Titian's artistic development also tells the story of the most influential Italian Renaissance art.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 323

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Author: Sir Claude Phillips

© 2023 Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© 2023 Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights of adaptation and reproduction reserved for all countries. Except as stated otherwise, the copyright to works reproduced belongs to the photographers who created them. In spite of our best efforts, we have been unable to establish the right of authorship in certain cases. Any objections or claims should be brought to the attention of the publisher.

Sir Claude Phillips

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Self-Portrait, 1565-1570.

Oil on canvas, 86 x 65 cm. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

THE EARLIER WORK OF TITIAN

THE LATER WORK OF TITIAN

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Paul III with the Camauro, c. 1545-1546.

Oil on canvas, 105 x 80.8 cm. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples.

INTRODUCTION

Titian is one of the greatest, most influential painters in Italian art. Though the names of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, figures so rarefied by centuries of adulation that we have all but lost sight of the power of their works, may ring more loudly to twenty-first century ears than that of the Venetian painter; though Raphael may excel him in his ethereal coolness and his perfect balance in both spirit and hand, Titian stands out instead for the broad scope of his work, flowing with the life-blood of humanity, rendering him more the poet-painter of the world and worldly creatures. When we think of the Entombment in the Louvre, the Assunta, the Retable of the Madonna Pesaro, the remnants of the Saint Peter Martyr, can we possibly discount or minimize his contribution to art and Western culture? Rarely do the pomp and splendour of a painter’s most representative achievements combine so consistently with a dignity and simplicity that rest within the bounds of nature. The sacred art of few other sixteenth-century painters has to an equal degree influenced the course of art history and moulded the style of the world as that of Titian, whose great ceremonial altarpieces manifest a passion that exaggerates only to better express its truth.

At least in the history of Italian art, Titian, if we are to treat him fairly, stands out as one of the top and maybe even the most important of portrait painters, successfully treating both men and women. Of other great practitioners in this genre, Leonardo evokes a truly unsettling power of fascination over his viewer, while Raphael and Michelangelo, along with Giorgione, mix wonderfully in the portraits of Sebastiano del Piombo. Let’s go back to Giorgione; he gave his subjects a poetic glamour by painting in an embellished but very realistic style. Lorenzo Lotto also has some good portraits, manifesting a real tenderness through his style of interpretation, uniquely combining his subjective feelings with a universal objectivity, the one rendering the other poetic. Other great Italian portrait painters include Moretto da Brescia, whose style is marked by tones of melancholy and aristocratic charm, and Giovanni Battista Moroni, who possessed the marvellous power to unite the spiritual and material aspects of human individuality without overdoing it. But even those who adore the aforementioned artists, if they wish to maintain any semblance of justice or seriousness in their study of art history, must recognize Titian’s style of portraiture as the strongest, most developed and most unique, at least with respect to the sheer number of artists his style has inspired.

His developments in the realm of landscape painting remain just as foundational as those of portraiture. Here, he had many great precursors and teachers whose lessons he synthesized into a groundbreaking whole. Until Claude Lorrain much later, none succeeded in entirely mimicking Titian’s manner of expressing the fullness of natural beauty without too strictly adhering to a factual, limited realism. Giovanni Bellini from his earliest beginnings in Padua displayed, unlike his great brother-in-law Mantegna, unlike the Squarcionesques and the Ferrarese, the true gift of the landscape painter. Atmospheric conditions invariably formed an important element of his compositions, shown clearly in the chilly solemnity of the landscape in his great Pietà of the Pinacoteca di Brera, the ominous sunset in the Agony in the Garden at the National Gallery, the cheerful all-pervading glow of the beautiful Sacred Conversation of the Uffizi and the mysterious illumination of the late Baptism of Christ at the Church of Santa Corona in Vincenza. Moving to Giorgione’s landscapes leads us into a perilous discussion of a quite fascinating subject, so various are his techniques even in the few well-established examples we have of his art, so exquisite an instrument of expression, so complete an illustration of the complex moods of his characters. But even based on the masterworks of his mature period such as the great altarpiece of Castelfranco, The Tempest[1] in the Galleria dell’Academia and the Three Philosophers in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Giorgione’s landscapes still have a slight flavour of the late medieval period just merging into full perfection. In his early period, it was Titian who would fully develop the Giorgionesque landscape, as in the Three Ages of Man, Sacred and Profane Love, and The Rustic Concert. Having learned from the best, he went on alone to surpass his masters in his radiantly beautiful representations of earth and sky that environ the figures of The Offering to Venus, the Bacchanal on Andros and Bacchus and Ariadne. These rich backgrounds of reposeful beauty reflect and build on those which enhance the finest of his Holy Familes and Sacred Conversations. More than the dramatic intensity and academic amplitude of its figures, it was the ominous grandeur of its landscape which won the Saint Peter Martyr its universal and well-documented fame. The same intimate relationship between landscape and figures reappears in the later Jupiter and Antiope (Venus of the Pardo) of the Louvre, marking a return to Giorgionesque repose and communion with nature. This can also be found in the later Rape of Europa, where the rainbow hues and bold sweep of the landscape recall the much earlier Bacchus and Ariadne. In the late masterpiece in monotone Shepherd and Nymph of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the sensuousness of the early Giorgionesque time reappears with an even greater force, tempered, as in the early days, by the imaginative temperament of the poet, and above all by the solemn atmosphere of mystery belonging to Titian’s final years.

Though Titian cannot boast the universality in art and science which lured da Vinci into a countless number of parallel pursuits, the vast scope of Michelangelo’s media and vision, or even the all-embracing curiosity of Albrecht Dürer, as a painter, he certainly covered more ground than any other master of the sixteenth century. While in more than one branch of his art Titian stood forth supreme and without rival, in the realm of monumental, decorative painting he yielded the palm to his younger rivals Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese, who showed themselves more practised and more successfully daring in this particular branch.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Pope Paul III Farnese (head uncovered), 1543.

Oil on canvas, 106 x 85 cm. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples.

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio), Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de’Medici and Luigi de’Rossi, c. 1517.

Oil on panel, 154 x 119 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Pope Paul III and his Nephews (Alessandro and Ottavio Farnese), c. 1545-1546.

Oil on canvas, 202 x 176 cm. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Ippolito de’Medici, c. 1532-1534.

Oil on canvas, 139 x 107 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence.

To find another instance of such supreme mastery of the brush, one must go to Antwerp, the great merchant city of the North as Venice was of the South. Rubens, who could arguably be described as the Flemish Titian, and who indeed owed much to his Venetian predecessor, though far less than did his own pupil Van Dyck, was during the first forty years of the seventeenth century on the same pinnacle of supremacy that the Cadorine master had occupied for a much longer period during the Renaissance. He too was without rival in the creation of those vast altarpieces that made famous the churches that owned them; he too was the finest painter of landscape of his time, using it as an accessory to the human figure. Moreover, he was a portrait painter who, in his greatest efforts – those sumptuous and almost truculent portraits d’apparat of princes, nobles and splendid dames – knew no superior, though his contemporaries were Van Dyck, Frans Hals, Rembrandt and Velázquez. Rubens united nature and man in a more demonstrative, seemingly closer embrace, drawing from a more exuberant vigour, but taking from the very closeness some of the stain of earth. Titian, though he was at least as genuine a realist as his successor, and one less content with the mere exterior of things, was filled with the spirit of beauty which was everywhere; in the mountain home of his birth as well as in the radiant home of his adoption, in himself as in his everyday surroundings. His art always demonstrated, even in its most human and least aspiring phases, the divine harmony, the suavity tempering natural truth and passion that distinguishes Italian art of the great periods from the finest art from elsewhere.

The relation between the two masters – both in the first line of the world’s painters – was much like that between Venice and Antwerp. The apogee of each city represented in its different way the highest point that modern Europe had reached of physical well-being and splendour, of material as distinguished from mental culture. Reality, with all its warmth and all its truth, in Venetian art was still reality. But it was reality made at once truer, wider and more suave by the method of its presentation. Idealisation, in the narrower sense of the word, could add nothing to the loveliness of such a land, to the stateliness, the splendid sensuousness devoid of the grosser elements, to the genuine naturalness of such a way of life. Art itself could only add to it the right accent, the right emphasis, the larger scope in truth, the colouring and illumination best suited to give the fullest expression to the beauties of the land, to the force, character and warm human charm of the people. This is what Titian, one of the best among his contemporaries of the greatest Venetian time, did with an incomparable mastery to which, in the vast field which his productions cover, it would be vain to seek for a parallel.

Other Venetian artists may, in one way or another, more irresistibly enlist our sympathies, or may shine out for the moment more brilliantly in some special branch of their art. Frequently, though, we still find ourselves invariably comparing them to Titian, not Titian to them; taking him as the standard for the measurement of even his greatest contemporaries and successors. Giorgione was of a finer fibre and, it could be said,

more happily combined the subtlest qualities of the painter and the poet, in his creation of a phase of art of which the penetrating exquisiteness has never in the succeeding centuries lost its hold on the world. But then Titian, saturated with the Giorgionesque, and only marginally less the poet-painter than his master and companion, carried the style to a higher pitch of material perfection than its inventor himself had been able to achieve. The gifted but unequal Pordenone, who showed himself so incapable of sustained rivalry with our master in Venice, had moments of a higher sublimity that Titian did not reach until he came to the extreme limits of old age. This assertion is not a mere paradox, as the great Madonna del Carmelo at the Galleria dell’Academia and the magnificent Trinity in the sacristy of the Cathedral of San Daniele near Udine prove. Yet who would venture to compare him on equal terms to the painter of the Assunta, the Entombment and the Supper at Emmaus? Tintoretto, at his best, had lightning flashes of illumination, a titanic vastness, an inexplicable power of perturbing the spirit and placing it in his own atmosphere, which may cause the imaginative not altogether unreasonably to put him forward as the greater figure in art. All the same, if it were necessary to make a definite choice between the two, who would not uphold the saner and greater art of Titian, even though it might leave us nearer to reality, though it might conceive the supreme tragedies, not less than the happy interludes, of the sacred drama, in the purely human spirit and with the pathos of earth? A not dissimilar comparison might be made between the portraits of Lorenzo Lotto and those of Titian. No other Venetian painter had that peculiar imaginativeness of Lotto, which caused him to unconsciously infuse into it much of his own tremulous sensitiveness and charm, while seeking to penetrate into the depths of human individuality. In this way no portraits of the sixteenth century provide so fascinating a series of riddles. Yet in deciphering them it is necessary to take into account the peculiar temperament of the painter himself, as well as the physical and mental characteristics of the sitter and the atmosphere of the time.[2]

Finally, in the domain of pure colour some will deem that Titian has serious rivals in those Veronese who became Venetians: the elder Bonifazi and the younger Paolo Veronese. That is to say, there will be found lovers of painting who prefer a brilliant mastery over contrasting colours in frank juxtaposition to a relatively restricted palette, used with more subtle, if less dazzling art than theirs, and resulting in a deeper, graver richness. That is, a more significant beauty, if less stimulating in gaiety and variety of aspect. No less a critic than Morelli himself pronounced the elder Bonifazio Veronese to be the most brilliant colourist of the Venetian school, and Dives and Lazarus of the Galleria dell’Academia and the Finding of Moses at the Brera are at hand to give solid support to such an assertion.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Aretino, 1545.

Oil on canvas, 96.7 x 77.6 cm. Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence.

Giovanni Bellini, The Doge Leonardo Loredan, c. 1501-1504.

Oil on poplar, 61.6 x 45.1 cm. The National Gallery, London.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Doge Marcantonio Trevisani, 1553.

Oil on canvas, 100 x 86.5 cm. Szépmūvészeti Múzeum, Budapest.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Self-Portrait, c. 1562-1564.

Oil on canvas, 96 x 75 cm. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

In some ways Paolo Veronese may, without exaggeration, be held as the greatest virtuoso among colourists, the most marvellous executant to be found in the whole range of Italian art. Starting from the cardinal principles in colour of the true Veronese, his precursors – painters such as Domenico and Francesco Morone, Liberale, Girolamo dai Libri, Cavazzola, Antonio Badile, and the rather later Brusasorci and Caliari – dared combinations of colour the most trenchant in their brilliancy as well as the subtlest and most unfamiliar. Unlike his predecessors, however, he preserved the stimulating charm while abolishing the abruptness of sheer contrast. This he did mainly by balancing and tempering his dazzling hues with huge architectural masses of a vibrant grey and large depths of cool dark shadow – brown shot through with silver. No other Venetian master could have painted the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine in the church of that name at Venice, the Allegory on the Victory of Lepanto in the Galleria dell’Academia, or the vast Nozze di Cana of the Louvre. All the same, this virtuosity, while it was in one sense a step in advance even of Giorgione, Titian, Palma, and Paris Bordone – constituting as it does a further development of painting from the purely decorative standpoint – must appear just a little superficial, a little self-conscious, by the side of the nobler, graver, and more profound, if in some ways more limited methods of Titian. With him, as with Giorgione, and indeed with Tintoretto, colour was above all an instrument of expression. The main effort was to realise the subject presented with splendid and penetrating truth, and colour in accordance with the true Venetian principle was used not only as the decorative vesture, but as the very body and soul of painting, as it is in nature.

To put forward Paolo Veronese as purely the dazzling virtuoso would be to show a singular ignorance of the true scope of his art. He could rise as high in dramatic passion and pathos as the greatest of them all on occasions; but these are precisely the times at which he most resolutely subordinated his colour to his subject and made the most poetic use of chiaroscuro. This can be seen in the great altarpiece The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian in the church of that name (San Sebastiano in Venice), Saint Francis receiving the Stigmata on a ceiling compartment of the Academy of Arts at Vienna, and the wonderful Crucifixion in the Louvre. Yet in this last piece the colour is not only in a singular degree interpretative of the subject, but at the same time technically astonishing, with certain subtleties of unusual juxtaposition and modulation, delightful to the craftsman, which are hardly seen again until the late nineteenth century. So that here we have the great Veneto-Veronese master escaping altogether from our theory, and showing himself at one and the same time profoundly moving, intensely significant, and admirably decorative in colour. Still, what was with him the splendid exception was with Titian, and those who have been grouped with Titian, the guiding rule of art. Though Titian remains the greatest Venetian colourist, he never condescended to vaunt all he knew, nor to select even the most legitimate of his subjects as a groundwork for bravura. He is the greatest painter of the sixteenth century simply because, being the greatest colourist of the higher order and in legitimate mastery of the brush second to none, he made the worthiest use of his unrivalled accomplishment. This was not merely to inspire applause due to his supreme pictorial skill and the victory over self-set difficulties, but above all to give the fullest and most legitimate expression to the subjects which he presented, and through them to himself.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Man with a Glove, c. 1520.

Oil on canvas, 100 x 89 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

THE EARLIER WORK OF TITIAN

Tiziano Vecelli was born in the last quarter of the fifteenth century at Pieve di Cadore, a district of the southern Tyrol then belonging to the Republic of Venice. He was the son of Gregorio di Conte Vecelli and his wife Lucia. His father came from an ancient family of the name of Guecello (or Vecellio), established in the valley of Cadore. An ancestor, Ser Guecello di Tommasro da Pozzale, had been elected Podesta of Cadore as far back as 1321.[3] The name Tiziano would appear to have been a traditional one in the family. Among others we find a contemporary Tiziano Vecelli, who was a lawyer of note concerned in the administration of Cadore, keeping up a kind of obsequious friendship with his famous cousin in Venice. The Tizianello who in 1622 dedicated an anonymous Life of Titian known as Tizianello’s Anonimo to the Countess of Arundel, and who died in Venice in 1650, was Titian’s cousin thrice removed.

Gregorio Vecelli was a valiant soldier, distinguished for his bravery in the field and his wisdom in the council of Cadore, but not, it may be assumed, possessed of wealth or, in a poor mountain district like Cadore, endowed with the means of obtaining it. At the age of nine, according to Dolce in the Dialogo della Pittura, or of ten, according to Tizianello’s Anonimo, Titian was taken from Cadore to Venice to begin his painting studies. Whether he had previously received some slight tuition in the rudiments of the art, or had only shown a natural inclination to become a painter, cannot be ascertained with any precision. What is much more vital in our study of the master’s life-work is to ascertain how far the scenery of his native Cadore left a permanent impression on his landscape art, and in what way his descent from a family of hardy mountaineers and soldiers of a certain birth and breeding contributed to shape his individuality in its development to maturity. It has been almost universally assumed that Titian throughout his career made use of the mountain scenery of Cadore in the backgrounds of his pictures. However, except for the great Battle of Cadore itself (now known only in Fontana’s print, in a reduced version of part of the composition to be found at the Galleria degli Uffizi, and in a drawing of Rubens at the Albertina), this is only true in a modified sense. Undoubtedly, both in the backgrounds to altarpieces, Holy Families, and Sacred Conversations, and in the landscape drawings of the type so freely copied and adapted by Domenico Campagnola, we find the jagged, naked peaks of the Dolomites aspiring to the heavens. The majority of the time, however, the middle distance and foreground to these is not the scenery of the higher Alps, with its abrupt contrasts, monotonous vesture of fir or pine forests clothing the mountain sides, and its relatively harsh and cold colouring. It is the richer vegetation of the lower slopes of the Friulan Mountains, or beautiful hills bordering upon the overflowing richness of the Venetian plain. Here the painter found greater variety, greater softness in the play of light, and richness more suitable to the character of Venetian art. He had the amplest opportunities for studying these tracts of country, as well as the more grandiose scenery of his native Cadore itself in the course of his many journeys from Venice to Pieve and back, as well as in his shorter expeditions on the Venetian mainland. The extent to which Titian’s Alpine origin, and his early upbringing among impoverished mountaineers, may account for his excessive eagerness to reap all the material advantages of his artistic pre-eminence, for his unresting energy when any post was to be obtained or any payment to be got in, must be a matter for individual appreciation. Josiah Gilbert – quoted by Crowe and Cavalcaselle[4] – pertinently asks, “Might this mountain man have been something of a ‘canny Scot’ or a shrewd Swiss?” In the earning of money, Titian was certainly all this, but in the spending he was large and liberal, inclined to splendour and profusion, particularly in the second half of his career. Vasari relates that Titian was lodging in Venice with his uncle, an “honourable citizen”, who, seeing his great inclination for painting, placed him under Giovanni Bellini, in whose style he soon became an expert. Dolce, in his Dialogo della Pittura, gives Sebastiano Zuccato, best known as a mosaic worker, as his first master. He then makes him pass into the studio of Gentile Bellini, and thence into that of the caposcuola (founder) Giovanni Bellini. Dolce then asserted that Titian took the last and by far the most important step of his early career by becoming the pupil and partner, or assistant, of Giorgione, but this has never been confirmed. Morelli[5] would prefer to leave Giovanni Bellini out of Titian’s artistic descent altogether. However, certain traces of Gentile’s influence may be observed in the art of the Cadorine painter, especially in the earlier portraiture, but particularly in the methods of technical execution generally. On the other hand, no existing earlier works suggest the view that he was part of the inner circle of Giovanni Bellini’s pupils – one of the discipuli (disciples), as some of these were fond of describing themselves. No young artist painting in Venice in the last years of the fifteenth century could, however, entirely withdraw himself from the influence of the veteran master, whether he actually belonged to his following or not. Giovanni Bellini exercised upon the contemporary art of Venice and the Veneto an influence as strong as that of Leonardo on that of Milan and the adjacent regions during his Milanese period. The latter not only stamped his art on the works of his own special school, but fascinated in the long run the painters of the specifically Milanese group which sprang from Foppa and Borgognone; such men as Ambrogio de’ Predis, Bernardino de’ Conti and the somewhat later Bernardino Luini. Even Alvise Vivarini, the vigorous head of the opposite school in its latest quattrocento development, bowed to the fashion for the Bellinesque conceptions of a certain class when he painted the Madonnas of the Redentore and San Giovanni in Bragora in Venice, and the similar one now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum. Bernard Berenson was the first to trace the artistic connection between Vivarini and Lorenzo Lotto, who was to a marked extent under the influence of Giovanni Bellini in such works as the altarpiece of Santa Cristina near Treviso, the Madonna and Child with Saints, and the Madonna and Child with Saint Peter Martyr in the Naples Museum. In the Marriage of Saint Catherine at Munich, though it belongs to the early period, he is, both as regards exaggerations of movement and delightful peculiarities of colour, essentially himself. Marco Basaiti, who up to the date of Alvise Vivarini’s death was intimately connected with him, and so far as he could faithfully reproduce the characteristics of his incisive style, was transformed in his later years into something very like a satellite of Giovanni Bellini. Cima, who in his technical processes belongs rather to the Vivarini than to the Bellini group, was to a great extent overshadowed, though never, as some would have it, absorbed to the point of absolute imitation, by his greater contemporary.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Man with a Glove, 1517-1520.

Oil on canvas, 88 x 73 cm. Musée Fesch, Ajaccio.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), A Man with a Quilted Sleeve, c. 1510.

Oil on canvas transferred from wood, 81.2 x 66.3 cm. The National Gallery, London.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of a Man, c. 1510.

Oil on canvas, 76.5 x 62.8 cm. Smoking Room at Ickworth, Bury St. Edmunds.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of a Lady (“La Schiavona”), c. 1510-1512.

Oil on canvas, 119.9 x 100.4 cm. The National Gallery, London.

What may legitimately intrigue in both Giorgione and Titian’s early years is not so much that in their earliest productions they leant to a certain extent on Giovanni Bellini, but that they were so soon independent. Neither of them is in any existing work seen to have the same absolutely dependent relationship with the veteran quattrocentist which Raphael for a time had with Perugino, and which Sebastiano Del Piombo in his early years had with Giorgione. This holds good to a certain extent also of Lorenzo Lotto, who in the earliest known examples – such as the Saint Jerome of the Louvre – is already emphatically Lotto. As his art passed through successive developments, however, he still showed himself open to more or less enduring influences from elsewhere. Sebastiano del Piombo, on the other hand, great master as he undoubtedly was in every phase, was never throughout his career free of influence. First, as a boy, he painted the puzzling Pietà, which, notwithstanding the authentic inscription, Bastian Luciani fuit descipulus Johannes Bellinus (sic) is so astonishingly like Cima that, without this piece of documentary evidence, it would even now pass as such. Next he became the most accomplished exponent of the Giorgionesque manner, save perhaps Titian himself. Then, migrating to Rome, he produced, in a quasi-Raphaelesque style still strongly tinged with the Giorgionesque, that series of superb portraits which under the name of Sanzio have acquired a worldwide fame. Finally, surrendering himself body and soul to Michelangelo, he remained enslaved by the tremendous genius of the Florentine to the very end of his career, only unconsciously allowing, from the force of early training and association, his Venetian origin to reveal itself.

Giorgione and Titian were both born in the last quarter of the fifteenth century; Giorgione around 1477 and Titian approximately ten years later, although there is still an ongoing debate on that matter. Lorenzo Lotto’s birth is to be placed around the year 1480. Palma was born around 1480, Pordenone possibly around the years 1483-1484 and Sebastiano Del Piombo around 1485. This shows that most of the great protagonists of Venetian art during the earlier half of the cinquecento were born within a short period of about fifteen years – between 1475 and 1490.

It is easy to understand how the complete renewal brought about by Giorgione on the basis of Bellini’s teaching and example operated to revolutionise the art of his own generation. He threw open to art the gates of life in its mysterious complexity, in its fullness of sensuous yearning mingled with spiritual aspiration. The fascination exercised both by his art and his personality was irresistible to his youthful contemporaries; the circle of his influence increasingly widened, until it might almost be said that the veteran Gian Bellini himself was brought within it. With Titian and Palma the germs of the Giorgionesque fell upon fruitful soil, and in each case produced a vigorous plant of the same family, yet with all its Giorgionesque colour of a quite distinctive kind. Titian, we shall see, carried the style to its highest point of material development, and made a new thing of it in many ways. Palma, with all his love of beauty in colour and form, in nature as in man, had a less finely attuned artistic temperament than Giorgione, Titian or Lotto. Morelli called attention to that energetic element in his mountain scenes, which in a way counteracted the marked sensuousness of his art, save when he interpreted the charms of the full-blown Venetian woman. The great Milanese critic attributed this to the rustic origin of the artist, showing itself beneath Venetian training. Is it not possible that a little of this frank unquestioning sensuousness on the one hand, of this terre à terre energy on the other, may have been reflected in the early work of Titian, though it be conceded that he influenced far more than he was influenced?[6] There is undoubtedly in his personal development of the Giorgionesque an extra element of something much nearer to the everyday world than is to be found in the work of his prototype, and this almost indefinable element is peculiar also to Palma’s art, in which it endures to the end. Thus there is a singular resemblance between the type of his fairly fashioned Eve in the important Adam and Eve of his earlier period now in the Prado – once, like so many other things, attributed to Giorgione – and the preferred type of youthful female loveliness as it is to be found in Titian’s Three Ages in the National Gallery of Scotland. This can also be found in his Sacred and Profane Love (Medea and Venus) in the Borghese Gallery, in such sacred pieces as the Madonna and Child with Saints Ulfo and Brigida which is now called Virgin and Child with Saints Dorothy and George in the Prado Museum of Madrid, and the large Madonna and Child with four Saints in Dresden. In both instances we have the Giorgionesque conception stripped of a little of its poetic glamour but retaining unabashed its splendid sensuousness, which is thus made to stand out more markedly. We notice, too, in Titian’s works of this particular group another characteristic which may be styled Palmesque, if only because Palma indulged in it in a great number of his Sacred Conversations and similar pieces. This is the contrasting of the rich brown skin and the muscular form of a male saint, or of a shepherd of the uplands, with the dazzling fairness, set off with hair of pale or ruddy gold, of a female saint or fair Venetian doing duty as a shepherdess or a heroine of Antiquity. Are we to look upon such distinguishing characteristics as these as wholly and solely Titian of the early period? If so, we ought to assume that what is most distinctively Palmesque in the art of Palma came from the painter of Cadore, who in this case should be taken to have transmitted to his brother in art the Giorgionesque in the less subtle shape into which he had already transmuted it. But should not such an assumption as this, well founded as it may appear in the main, be made with all the allowances that the situation demands?

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Annunciation, c. 1519-1523.

Oil on wood, 179 x 207 cm. Il Duomo, Treviso.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), The Virgin and Child between Saint Anthony of Padua and Saint Roch, c. 1510.

Oil on canvas, 92 x 133 cm. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

When a group of young and enthusiastic artists, eager to overturn barriers, are found painting more or less together, it is not so easy to unravel the tangle of influences and draw hard-and-fast lines everywhere. One or two more modern examples may roughly serve to illustrate. Take, for instance, the friendship that developed between the youthful Bonington and the young Delacroix while they copied together in the galleries of the Louvre. One would communicate to the other something of the stimulating quality, the frankness, and variety of colour which at that moment distinguished the English from the French school; the other would contribute, with the fire of his romantic temperament, to the art of the young Englishman who was some three years his junior. And with the famous trio of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood – Millais, Rossetti and Holman Hunt – who is to state ex cathedra where influence was received, where transmitted; or whether the first may fairly be held to have been, during the short time of their complete union, the master-hand, the second the poet-soul, the third the conscience of the group?

In days of artistic upheaval and growth such as the last years of the fifteenth century and the first years of the sixteenth, the milieu must count for a great deal. It must be remembered that the men who most influence a time, whether in art or letters, are just those who, deeply rooted in it, come forth as its most natural development. Let it not be doubted that when the first sparks of the Promethean fire had been lit in Giorgione’s breast, which, with the soft intensity of its glow, warmed into full-blown perfection the art of Venice, that fire ran like lightning through the veins of all the artistic youth. The blood of his contemporaries and juniors was of the material to ignite and flame like his own.

The great Giorgionesque movement in Venetian art was not a question merely of school, of standpoint, of methods adopted and developed by a brilliant galaxy of young painters. It was not alone that “they who were excellent confessed, that he (Giorgione) was born to put the breath of life into painted figures, and to imitate the elasticity and colour of flesh, etc.”[7] It was also that the Giorgionesque in conception and style was the outcome of the moment in art and life, just as the Pheidian mode had been the necessary climax of Attic art and Attic life aspiring to reach complete perfection in the fifth century B.C.; just as the Raphaelesque appeared the inevitable outcome of those elements of lofty generalisation, divine harmony, grace clothing strength, which, in Florence and Rome, as elsewhere in Italy, were culminating in the first years of the cinquecento. This was the moment, too, when – to take one instance only among many – the ex-Queen of Cyprus, the noble Venetian Caterina Cornaro, held her little court at Asolo, where, in accordance with the spirit of the moment, the chief discourse was always of love. In that reposeful kingdom, which could in miniature offer to Caterina’s courtiers all the pomp and charm without the drawbacks of sovereignty, Pietro Bembo wrote for “Madonna Lucretia Estense Borgia Duchessa illustrissima di Ferrara,” and caused to be printed by Aldus Manutius, the leaflets which, under the title Gli Asolani, ne’quali si ragiona d’amore,[8] soon became a famous book in Italy.

The Virgin and Child in the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna, popularly known as La Zingarella, which is accepted as the first in order of date among the works of this class, is still to a certain extent Bellinesque in the mode of conception and arrangement. Yet, in the depth, strength and richness of the colour-chord, in the atmospheric spaciousness and charm of the landscape background, in the breadth of the draperies, it is already Giorgionesque. Even Titian here asserts himself, and lays the foundation of his own manner. The characteristics of the divine Child differ widely from those adopted by Giorgione in the altarpieces of Castelfranco and the Prado Museum at Madrid. The Virgin is a woman beautified only by youth and the intensity of maternal love. Both Giorgione and Titian in their loveliest types of woman are sensuous compared with the Tuscans and Umbrians, or with such painters as Cavazzola of Verona and the suave Milanese, Bernardino Luini. But Giorgione’s sensuousness is that which may easily characterise the goddess, while Titian’s is that of the woman, much nearer to the everyday world in which both artists lived.

The famous Christ Carrying the Cross in the Chiesa di San Rocco in Venice was first ascribed by Vasari to Giorgione in his Life of the Castelfranco painter, then in the subsequent Life of Titian given to that master, but to a period very much too late in his career. The biographer quaintly adds: “This figure, which many have believed to be from the hand of Giorgione, is today the most revered object in Venice, and has received more charitable offerings in money than Titian and Giorgione together ever gained in the whole course of their life.” Indeed the embers of this debate remain hot to this day, as the Scuola di San Rocco now reattributes this work to the Castelfranco master, Giorgione. The picture, which presents “Christ dragged along by the executioner, with two spectators in the background,” resembles most among Giorgione’s authentic creations the Christ bearing the Cross. The resemblance is not, however, one of colour and technique, since this latter – one of the earliest Giorgiones – still recalls Giovanni Bellini, and perhaps even more strongly Cima; it is one of type and conception. In both renderings of the divine countenance there seems to be a sinister, disquieting look, almost a threat underlying that expression of serenity and humiliation accepted which is proper to the subject. Crowe and Cavalcaselle have called attention to a certain disproportion in the size of the head, as compared with that of the surrounding actors in the scene. A similar disproportion is to be observed in another early Titian, the