24,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Blackwell Introductions to Literature

- Sprache: Englisch

This compelling study explores the inextricable links between the Nobel laureate’s aesthetic practice and her political vision, through an analysis of the key texts as well as her lesser-studied works, books for children, and most recent novels.

- Offers provocative new insights and a refreshingly original contribution to the scholarship of one of the most important contemporary American writers

- Analyzes the celebrated fiction of Morrison in relation to her critical writing about the process of reading and writing literature, the relationship between readers and writers, and the cultural contributions of African-American literature

- Features extended analyses of Morrison’s lesser-known works, most recent novels, and books for children as well as the key texts

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 292

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Blackwell Introductions to Literature

Title page

Copyright page

Acknowledgments

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1 The Bluest Eye and Sula

The Bluest Eye

Sula

CHAPTER 2 Song of Solomon and Tar Baby

Song of Solomon

Tar Baby

CHAPTER 3 Beloved

CHAPTER 4 Jazz and Paradise

Jazz

Paradise

CHAPTER 5 Books for Young Readers, Love and A Mercy

Love

A Mercy

Epilogue: Home

Further Reading

Works Cited

Index

Blackwell Introductions to Literature

This series sets out to provide concise and stimulating introductions to literary subjects. It offers books on major authors (from John Milton to James Joyce), as well as key periods and movements (from Old English literature to the contemporary). Coverage is also afforded to such specific topics as “Arthurian Romance.” All are written by outstanding scholars as texts to inspire newcomers and others: nonspecialists wishing to revisit a topic, or general readers. The prospective overall aim is to ground and prepare students and readers of whatever kind in their pursuit of wider reading.

Published

1.

John Milton

Roy Flannagan

2.

Chaucer and the Canterbury Tales

John Hirsh

3.

Arthurian Romance

Derek Pearsall

4.

James Joyce

Michael Seidel

5.

Mark Twain

Stephen Railton

6.

The Modern Novel

Jesse Matz

7.

Old Norse-Icelandic Literature

Heather O’Donoghue

8.

Old English Literature

Daniel Donoghue

9.

Modernism

David Ayers

10.

Latin American Fiction

Philip Swanson

11.

Re-Scripting Walt Whitman

Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price

12.

Renaissance and Reformations

Michael Hattaway

13.

The Art of Twentieth-Century American Poetry

Charles Altieri

14.

American Drama 1945–2000

David Krasner

15.

Reading Middle English Literature

Thorlac Turville-Petre

16.

American Literature and Culture 1900–1960

Gail McDonald

17.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets

Dympna Callaghan

18.

Tragedy

Rebecca Bushnell

19.

Herman Melville

Wyn Kelley

20.

William Faulkner

John T. Matthews

21.

Toni Morrison

Valerie Smith

This edition first published 2012

© 2012 Valerie Smith

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Valerie Smith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smith, Valerie, 1956–

Toni Morrison : writing the moral imagination / Valerie Smith.

p. cm. – (Blackwell introductions to literature ; 42)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4051-6033-9 (hardback)

1. Morrison, Toni–Criticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PS3563.O8749Z856 2012

813'.54–dc23

2012012320

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

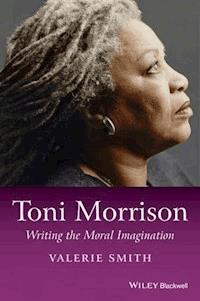

Cover image: Photo of Toni Morrison. © Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Cover design by Design Deluxe

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to many people and organizations for the intellectual, financial and emotional support I received during the process of writing this book. First and foremost, I thank Toni Morrison for the gift of her eloquent, rigorous, and inspired body of work. Her writing across a wide range of genres has remapped the landscape of African American, US, and global literatures; revised our understanding of our national history; and challenged us to reconsider our understanding of constructions of race, gender, sex, class, and power. I am privileged to have had this opportunity to write a book about one of the most gifted, versatile, and influential writers and intellectuals of our time. I thank her for graciously supporting this project and for spending hours in conversation with me.

I am grateful also to Emma Bennett, Isobel Bainton, Louise Butler, Caroline Clamp, Bridget Jennings, Ben Thatcher, and Kathy Syplywczak at Wiley-Blackwell for their commitment to this project and for their patience and support in seeing it to completion. I thank Alison Waggitt for indexing the book with such care and attention.

I owe a profound debt of gratitude to the Office of the Dean of the Faculty at Princeton University, the School for Historical Studies at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), the Guggenheim Foundation, and the Alphonse G. Fletcher Foundation for providing me with support during the years I worked on this book. I am especially grateful to Heinrich von Staden, Professor Emeritus of Classics and History of Science at IAS, for encouraging me to apply to the Institute and for his consistent interest in my project.

The Liguria Study Center in Bogliasco, Italy provided me with space and time to write and revise much of this book. The stunning views of the Ligurian Sea and the spacious, light and airy writing studio and accommodations offered the ideal context in which to work. Special thanks to the gracious, good-humored, and exceptionally efficient staff – Ivana Folle, Alessandra Natale, and Valeria Soave – and the nurturing and brilliant group of fellows – Rosa del Carmen Martinez Ascobereta, Isis Ascobereta, Linda Ben-Zvi, Sam Ben-Zvi, Angela Bourke, Mags Harries, Lajos Heder, Joel Kaye, Erika Latta, Thea Lurie, Michael McMahon, and Roberta Vacca – for creating a vibrant and intellectually stimulating community of friends and colleagues.

I am grateful for the invitations I’ve received to speak about Morrison’s work at colleges and universities both in the US and abroad. I thank Theresa Delgadillo at the Ohio State University; Gillian Logan and Rick Chess at the University of North Carolina, Asheville; Jacquelyn McLendon at the College of William and Mary; Aoi Mori at the Hiroshima Jogakuin University; Azusa Nishimoto at the Aoyama Gakuin University; Sonnet Retman at the University of Washington; and Leslie Wingard at the College of Wooster for allowing me to share my work and to benefit from conversations with their students and colleagues. I also thank Sandra Bermann for inviting me to interview Toni Morrison at a meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association; that conversation provided me with the first opportunity to think about Morrison’s books for young readers.

Jessica Asrat, Adrienne Brown, and Nicole Hendrix provided valuable research assistance; I thank these three enormously gifted women for their insight and support. I am also deeply grateful to my friends Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham and Karen Harris and Rob Gips for offering me opportunities to retreat to beautiful places where which I could think, read and write.

Many of the ideas I explore in this book grew out of discussions in the seminars on Toni Morrison I taught both at Princeton and at the Bread Loaf School of English in Asheville, NC. I am grateful to all of the enthusiastic and inspiring students who enrolled in those classes and participated in them which such passion and intellectual fervor, especially: Jessica Asrat, Eli Bromberg, Anna Condella, Alexis Fisher, Diane Humphreys-Barlow, Morgan Kennedy, Genay Kirkpatrick, E. Palmer Seeley, Mike Spara, Candice Weddington, and Mona Zhang.

In Beloved, Paul D famously says of Sethe: “She is a friend of my mind.” I am blessed to have a community of “friends of my mind.” Thank you to Emily Bartels, Lawrence Bobo, Mary Pat Brady, Daphne Brooks, Abena Busia, Benjamin Colbert, Deborah Raikes-Colbert, Theresa Delgadillo, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Farah Jasmine Griffin, Karen Harris, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Sue Houchins, Tera Hunter, Claudia Johnson, Arthur Little, Marcyliena Morgan, Keidra Morris, Beverly Moss, Dorothy Mullen, Jeff Nunokawa, Carla Hailey Penn, Sonnet Retman, Rita Rothman, Nicole Shelton, Lisa Thompson, Mary Helen Washington, Leslie Wingard, Judi Wortham-Sauls, and Richard Yarborough for the gifts of their intellectual and spiritual companionship.

Finally, I thank my beloved family for their unwavering support for all my endeavors: my dear parents, Will and Josephine Smith; my siblings, Daryl and Raissa Smith, and Vera Smith-Winfree and Glenn Winfree; my “in-laws,” Ruth and Walter Winfree; and my nieces and nephews, Alison Smith, Ellis Winfree, Gage Smith and Miriam Smith. I thank Ase Gassaway for his encouragement, companionship, faith and love.

Valerie SmithJuly 2012

INTRODUCTION

Toni Morrison ranks among the most highly-regarded and widely-read fiction writers and cultural critics in the history of American literature. Novelist, editor, playwright, essayist, librettist, and children’s book author, she has won innumerable prizes and awards and enjoys extraordinarily high regard both in the United States and internationally.1 Her work has been translated into many languages, including German, Spanish, French, Italian, Norwegian, Finnish, Japanese, and Chinese and is the subject of courses taught and books and articles written by scholars all over the world. It speaks to academic and mass audiences alike; scholars have interpreted her work from myriad perspectives, including various approaches within cultural studies, African Americanist, psychoanalytic, neo-Marxist, linguistic, and feminist methodologies, while four of her novels were Oprah’s Book Club selections. She invites frequent comparison with the best-known writers of the global canon: Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner, Zora Neale Hurston, James Joyce, Thomas Hardy, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, and others. Because of her broad appeal, throughout her career, readers and critics alike have sought to praise Morrison by calling her work “universal.”

The adjective “universal” has typically been applied to work in any medium that speaks to readers, viewers, or audience members whatever their race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, or socioeconomic status. Art described as “universal” is contrasted implicitly or explicitly with work that is labeled “provincial,” that is, more explicitly grounded in the culture, lore, or vernacular of an identifiable group. But for all its “universality,” Morrison’s writing is famously steeped in the nuances of African American language, music, everyday life, and cultural history.2 Even more precisely, most of her novels are concerned with the impact of racial patriarchy upon the lives of black women during specific periods in American history, such as the Colonial period, or the eras of slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and Civil Rights.

It should not surprise us that Morrison considers the appellation “universal” to be a dubious distinction. In a 1981 interview with Thomas LeClair she remarks:

It is that business of being universal, a word hopelessly stripped of meaning for me. Faulkner wrote what I suppose could be called regional literature and had it published all over the world. It is good – and universal – because it is specifically about a particular world. If I tried to write a universal novel, it would be water.3

Here Morrison famously challenges the notion that universal art is unmarred by markers of cultural specificity. Instead, she argues that only by being specific can a work truly be universal. Rather than aspiring to a culturally de-racinated discourse, then, in her fiction she seeks ways of writing about race without reproducing the tropes of racism, or as she puts it in a 1997 essay entitled “Home”: “How to be both free and situated; how to convert a racist house into a race-specific yet nonracist home.”4

As Dwight McBride, Cheryl A. Wall, and others have argued, one way to understand Morrison’s career is to consider the interconnections among her roles as writer of fiction and nonfiction, editor, and teacher.5 On numerous occasions she has herself eschewed the distinction between scholarship or criticism and the creative arts, as for example, she writes in a 2005 essay:

It is shortsighted to relegate the practice of creative arts in the academy to the status of servant to its scholarship, to leave the practice of creative arts along the edge of the humanities as though it were an afterthought, an aspirin to ease serious pain, or a Punch-and-Judy show offering comic relief in the midst of tragedy.6

Her adroit use of language notwithstanding, at their core, all of her novels provide astute analyses of cultural and historical processes. Likewise, their critical insightfulness notwithstanding, Morrison’s essays and articles make powerful use of narrative and imagery. One never forgets that she is a novelist writing analytic prose or a social and cultural critic writing fiction.

She has been a teacher, editor, critic, and fiction writer, and throughout her career, she has worked in two or more of these areas simultaneously. She taught at a number of colleges and universities while writing fiction, and she published five novels during the period when she both worked as senior editor at Random House and taught. As she continues to produce one path-breaking novel after another, she has also written influential speeches, critical and political essays and articles, libretti, a book of literary criticism, several children’s books, and edited two interdisciplinary cultural studies volumes. Moreover, the project of her work outside the realm of fiction writing is tied inextricably to the aims of her fiction itself. To understand the extent of her contributions and achievements, then, it behooves us to consider the nature of those connections.

Throughout her critical writing, Morrison asserts that the role of the reader must be active, not passive; indeed, she suggests that the reader must be actively engaged with the author in a dynamic process out of which textual meaning derives. In “The Dancing Mind,” her 1996 acceptance speech delivered on the occasion of receiving the Distinguished Contribution to American Literature Award from the National Book Award Foundation, she writes:

Underneath the cut of bright and dazzling cloth, pulsing beneath the jewelry, the life of the book world is quite serious. Its real life is about creating and producing and distributing knowledge; about making it possible for the entitled as well as the dispossessed to experience one’s own mind dancing with another’s; about making sure that the environment in which this work is done is welcoming, supportive.7

In part, this view of the relationship between reader and writer reflects the influence of other forms of cultural production and performance, such as dance, oratory, and jazz, upon her work. As she observes in an essay entitled “Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation”(1984), in her writing she seeks to inspire her reader to respond to a written text as she or he would to a worship service or a musical performance:

[Literature] should try deliberately to make you stand up and make you feel something profoundly in the same way that a Black preacher requires his congregation to speak, to join him in the sermon … that is being delivered. In the same way that a musician’s music is enhanced when there is a response from the audience. Now in a book, which closes, after all – it’s of some importance to me to try to make that connection – to try to make that happen also. And, having at my disposal only the letters of the alphabet and some punctuation, I have to provide the places and spaces so that the reader can participate. Because it is the affective and participatory relationship between the artist or the speaker and the audience that is of primary importance, as it is in these other art forms I have described.8

This quality of engagement is also important to her work because it is a means through which she dismantles the hierarchies that undergird systemic forms of oppression. For Morrison, language and discursive strategies are not ancillary to systems of domination. Rather, they are central means by which racism, sexism, classism, and other ideologies of oppression are maintained, reproduced, and transmitted. As a writer, she may not be inclined or equipped to intervene in the policy arena to bring about social change, but she seeks to use her artistic talents to illuminate and transform the ways in which discursive practices enshrine structures of inequality: “eliminating the potency of racist constructs in language is the work I can do.”9 For this reason, Morrison does not spoon-feed meaning to her readers. For her fiction to serve the function she intends, the reader must be willing to re-read, to work. Hence her novels refuse to tell us overtly what they mean:

[Her novels other than Sula] refuse the ‘presentation’: refuse the seductive safe harbor; the line of demarcation between the sacred and the obscene, public and private, them and us. Refuse, in effect, to cater to the diminished expectations of the reader, or his or her alarm heightened by the emotional luggage one carries into the black-topic text.10

Elsewhere she has written: “I want my fiction to urge the reader into active participation in the non-narrative, nonliterary experience of the text, which makes it difficult for the reader to confine himself to a cool and distant acceptance of data. … I want to subvert [the reader’s] traditional comfort so that he may experience an unorthodox one: that of being in the company of his own solitary imagination.”11

The opening of Beloved, for example, unsettles the reader epistemologically in order to invoke the slaves’ experience of dislocation. Similarly, the reader of A Mercy is likely to be confused by references and allusions to events that have yet to unfold; our disorientation enacts the confusion of the novel’s seventeenth-century characters making their way within a world that will become the United States of America.

Moreover, in her fiction and criticism alike, she considers the strategies by which racial ideologies are constructed, maintained, and circulated. One of her most famous essays, “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature” (1989), provides the framework of her influential book-length study, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992). Here she explores the significance of the silence surrounding the topic of race in the construction of American literary history. For her, many critics’ refusal to acknowledge the role of race in the making of the US literary canon exemplifies the unspeakability of race in American culture. To her mind, custodians of the canon retreat into specious arguments about quality and the irrelevance of ideology when defending the critical status quo against charges of racial bias. Moreover, Morrison is skeptical about arguments based on the notion of critical quality, given that aesthetic judgments are inevitably subjective, often self-justifying, and contested.

In this essay she also reflects upon some of the ways in which scholars of African American literature have responded to attempts to delegitimize black literary production. While some critics deny the very existence of African American art, African Americanists have rediscovered texts that have long been ignored, underread, or misinterpreted; have sought to make places for African American writing within the canon; and have developed innovative strategies of interpreting these works. Other critics dismiss African American art as inferior – “imitative, excessive, sensational, mimetic … and unintellectual, though very often ‘moving,’ ‘passionate,’ ‘naturalistic,’ ‘realistic,’ or sociologically ‘revealing.’ ”12 Those critics, Morrison notes, often lack the acumen, inclination, or commitment to understand the complexity of African American literature. In response to such judgments, African Americanists have mobilized and interpreted recent theories and methodologies (such as deconstruction, psychoanalysis, feminism, and performance theory, to name a few) in relation to African American texts in order to intervene in current critical discourses and debates. Morrison also sharply criticizes those who seek to ennoble African American art by assessing it in relation to the ostensibly universal criteria of Western art. She remarks that such comparisons fail to do justice both to the inherent qualities of the texts and to the myriad traditions of which they are a part.

She describes three strategies critics might utilize in order to undermine such efforts to marginalize African American art and literature. To counteract such assaults on forms of black cultural production, she first proposes that critics develop a theory of literature that responds to the tradition’s vernacular qualities: “one that is based on its culture, its history, and the artistic strategies the works employ to negotiate the world it inhabits” (p. 11). Second, she suggests that the canon of classic, nineteenth-century literature be reexamined to illuminate how the African American cultural presence is expressed even in its ostensible absence from white-authored, ostensibly race-neutral texts. Third, she recommends that contemporary literary texts, whether written by white authors or authors of color, be studied for evidence of this presence.

“Unspeakable Things” centers on the second and third strategies; here, Morrison seems intrigued with the rich possibilities contained in the idea of absence:

We can agree, I think, that invisible things are not necessarily “not-there;” that a void may be empty, but it is not a vacuum. In addition, certain absences are so stressed, so ornate, so planned, they call attention to themselves; arrest us with intentionality and purpose, like neighborhoods that are defined by the population held away from them. (p. 11)

Her incisive reading of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick as a critique of the power of whiteness exemplifies the second strategy she outlines and indicates the subtext of race that critics of that classic text long ignored. She demonstrates the third strategy by analyzing the opening sentence of each of her novels to suggest ways in which African American culture becomes legible in black texts. Morrison’s readings of her own prose display the acuity of her critical sensibility and her use of language to reveal the subtleties of African American cultural life.

Her book-length critical study, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1993), is now widely understood to be an extraordinarily influential contribution to discussions of race and US literature. It expands upon the enterprise of “Unspeakable Things” and explores the impact of constructions of race upon a range of key texts in the American literary tradition. As part of the complex project of this work, Morrison establishes the discourses of race within which texts by Willa Cather, Melville, Edgar Allan Poe, Ernest Hemingway, and others participate. By making explicit the assumptions about race inscribed within the texts upon which she focuses, Morrison reveals the centrality of ideas of whiteness and blackness to the idea of America. As she writes:

It has occurred to me that the very manner by which American literature distinguishes itself as a coherent entity exists because of this unsettled and unsettling population [Africans and African Americans]. Just as the formation of the nation necessitated coded language and purposeful restriction to deal with the racial disingenuousness and moral frailty at its heart, so too did the literature, whose founding characteristics extend into the twentieth century, reproduce the necessity for codes and restriction. Through significant and underscored omissions, startling contradictions, heavily nuanced conflicts, through the way writers peopled their work with the signs and bodies of this presence – one can see that a real or fabricated Africanist presence was crucial to their sense of Americanness.13

In the introductions to her two edited collections, Morrison draws analogies between constructions of race in literature and in real life to explore how strategies of racialization functioned within the discourse surrounding two high-profile cultural events from the 1990s. In “Introduction: Friday on the Potomac,” which begins Race-ing Justice, En-gendering Power: Essays on Anita Hill, Clarence Thomas, and the Construction of Social Reality (1992), Morrison refers to Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe to demonstrate that because of the proliferation of racist and sexist stereotypes, both then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill (his former attorney-adviser and special assistant who accused him of sexual harassment) were rendered at once overly familiar and incomprehensible during Thomas’s Senate confirmation hearings.14 Reading the figure of Thomas and the discourse surrounding the hearings in light of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, she explores some of the historically-grounded patterns of domination, acquiescence, and resistance that are reenacted in contemporary cultural and political debates. As Sami Ludwig has noted, in her introduction, “Morrison takes the binary out of the realm of mere language structure and contextualizes it in a historical realm of human interaction.”15

Likewise, in “The Official Story: Dead Man Golfing,” the introduction to Birth of a Nation’hood: Gaze, Script, and Spectacle in the O. J. Simpson Case (1997), Morrison reads Herman Melville’s “Benito Cereno” in relation to Simpson’s 1994 criminal trial for the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman. In her analysis, she explores ways in which raced and gendered national narratives produce an official story that eclipses actual events.

* * *

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford on February 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio, a multiracial steel town. Her parents and other members of her extended family bequeathed to her both a legacy of resistance to oppression and exploitation and an appreciation of African American folklore and cultural practices. Both sets of grandparents migrated from the South to Ohio in hopes of leaving virulent forms of racism behind and finding greater opportunities for themselves and their children; her maternal grandparents came from Alabama, and her father’s family came from Georgia.

The music, folklore, ghost stories, dreams, signs, and visitations that are so vividly evoked in her fiction pervaded Morrison’s early life and inspired her to capture the qualities of African American cultural expression in her prose. Indeed, Morrison and her critics alike have described the influence of orality, call and response, jazz and dance in her narratives. Yet the presence of myth, enchantment, and folk practices in her work never offers an escape from the sociopolitical conditions that have shaped the lives of African Americans. Cultural dislocation, migration, and urbanization provide the inescapable contexts within which her explorations of the African American past occur.

Literature also played an important role in her childhood and youth. The only child in her first-grade class who was able to read when she entered school, Morrison read widely across a variety of literary traditions as an adolescent and considered the classic Russian novelists, Flaubert, and Jane Austen among her favorites. She was not exposed to the work of previous generations of black women writers until she was an adult. Her delayed introduction to the work of earlier black women writers does not, to her mind, mean that she writes outside that tradition. Rather, the thematic and aesthetic connections between her work and theirs confirm her sense that African American women writers conceive of character and circumstance in specific ways that reflect the historical interconnections between and among constructions of race, gender, sexuality, class, and region. As she remarks in a conversation with the novelist Gloria Naylor:

[People] who are trying to show certain kinds of connections between myself and Zora Neale Hurston are always dismayed and disappointed in me because I hadn’t read Zora Neale Hurston except for one little story before I began to write. … The fact that I never read her and still there may be whatever they’re finding, similarities and dissimilarities, whatever such critics do, makes the cheese more binding, not less, because it means that the world as perceived by black women at certain times does exist.16

Morrison has observed that although the books she read in her youth “were not written for a little black girl in Lorain, Ohio … they spoke to [her] out of their own specificity.” Her early reading inspired her later “to capture that same specificity about the nature and feeling of the culture [she] grew up in.”17

After graduating with honors from Lorain High School, she enrolled at Howard University, where she majored in English and minored in classics and from which she graduated in 1953. She describes the Howard years with some measure of ambivalence. She was disappointed with some features of life at the university, which, she has said, “was about getting married, buying clothes and going to parties. It was also about being cool, loving Sarah Vaughan (who only moved her hand a little when she sang) and MJQ [the Modern Jazz Quartet].”18 But she was inspired by her participation in the Howard University Players, a student-faculty repertory troupe that took plays on tour throughout the South during the summers. As Susan L. Blake suggests, these trips enhanced the stories of injustice Morrison’s grandparents had told her about their early lives in Alabama.19

After Howard, she received an MA from Cornell University in 1955, where she wrote a thesis on the theme of suicide in the works of William Faulkner and Virginia Woolf. She then taught at Texas Southern University in Houston from 1955 to 1957 and for 5 years at Howard, where her courses included the freshman humanities survey that focused on “masterpieces of Western literature from Greek and Roman mythology to the King James Bible to twentieth-century novels.”20 Her students at Howard included one of the future leading figures in African American literary and cultural studies, Houston A. Baker, Jr.; future autobiographer Claude Brown; and the future leader of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, Stokely Carmichael. While at Howard she married Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architect, in 1958 (they divorced in 1964) and had two sons, Harold Ford and Slade Kevin. During this period she also joined a writers’ group, for which she wrote a young story about a young black girl who wanted blue eyes. That story would become the basis of her first novel.

When her marriage ended, Morrison returned to Lorain with her two young sons for an eighteen-month period. Subsequently, she began to work in publishing, first as an editor at L. W. Singer, the textbook subsidiary of Random House in Syracuse, New York, and then as senior editor at the headquarters of Random House in Manhattan. While living in Syracuse, she worked on the manuscript of her first novel at night after her children were asleep. In her conversation with Gloria Naylor, she suggests that work on the novel became a way for her to write herself back into existence:

I had written this little story earlier just for some friends, so I took it out and I began to work it up. And all of those people were me. I was Pecola, Claudia. … I was everybody. And as I began to do it, I began to pick up scraps of things I had seen or felt, or didn’t see or didn’t feel, but imagined. And speculated about and wondered about. And I fell in love with myself.21

She sent part of a draft to an editor who liked it enough to suggest that she finish it. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston published The Bluest Eye in 1970.

Although Morrison was not familiar with much writing by other African American writers when she began her first novel, she has had a profound impact upon the careers of a range of black authors. As senior editor at Random House, she edited influential texts in African American cultural and intellectual history, including Angela Davis: An Autobiography, Davis’s Women, Race, and Class, Ivan Van Sertima’s They Came Before Columbus, and Muhammad Ali’s The Greatest, My Own Story. Moreover, she brought a number of black writers to that publisher’s list, including Toni Cade Bambara, Wesley Brown, Lucille Clifton, Henry Dumas, Leon Forrest, June Jordan, Gayl Jones, John McCluskey, and Quincy Troupe.22

As Cheryl Wall argues, one can trace deep connections between Morrison’s editorial work and her fiction in several ways. Generally speaking, she and the authors she published sought to preserve the lives, voices and wisdom that have been left out of mainstream histories. Moreover, The Black Book (1974) the legendary compendium of ephemera, photographs, songs, photographs, and dream interpretations that she edited, documents the creativity and resilience, suffering and pain of both famous and unknown African Americans during and after slavery. That book contains the article about Margaret Garner’s murder of her daughter that inspired Beloved.

To date, Morrison’s publications include ten novels, six books for children, one short story, one book of literary criticism, one edited and one co-edited volume of cultural criticism, and scores of critical essays, reviews, and articles. In her essays and interviews, she often compares the craft of writing to dance, music, and painting.23 Her fiction reflects the influence of other art forms, such as jazz, dance, photography, and the visual arts, and she frequently collaborates with other artists. She has written a play, Dreaming Emmett, which premiered at the Marketplace Theater in Albany, New York in 1986, song cycles with composers, and the libretto for the opera “Margaret Garner” with music by Richard Danielpour. After premieres in Detroit, Cincinnati, and Philadelphia, “Margaret Garner” was staged in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 2006 and opened at New York City Opera in September 2007.24

In fall 2006, the Musee du Louvre in Paris invited her to participate in its “Grand Invité” program, under the auspices of which she curated a month-long series of events on the theme of “The Foreigner’s Home.” Using Théodore Géricault’s painting “The Raft of the Medusa” (1819) as a point of departure, Morrison organized a multidisciplinary program “focused on the pain – and rewards – of displacement, immigration and exile.” She participated in readings, lectures and panels, and invited artists and curators from around the world to explore this theme. Highlights included a panel discussion on the subject of displacement and language featuring Morrison, Edwidge Danticat (a US writer born in Haiti), Michael Ondaatje (a Sri Lanka-born writer educated in the United Kingdom and living in Canada), and Boubacar Boris Diop (a Senegalese novelist who writes in French and Wolof); an exhibit that paired drawings by Géricault, Charles Le Brun, Georges Seurat, and Edgar Degas with films and videos that focused on the body; and an installation entitled “Foreign Bodies” inspired by Francis Bacon’s last, unfinished portrait. In this last piece, the American choreographer William Forsythe and the German sculptor and video artist Peter Welz produced a dance in which Forsythe, with graphite attached to his hands and feet, performed on a large sheet of white paper: “thus a dance inspired by a drawing became itself a drawing.”25

Throughout her career Morrison has taught at a number of colleges and universities, including Yale, Bard, the State University of New York at Purchase, and the State University of New York at Albany. From 1988 until her retirement in 2006, she held the Robert F. Goheen Professorship of the Humanities at Princeton University. While at Princeton she taught a range of courses on African American literature and creative writing. As Wall notes, in one course she “tried out the ideas of the Africanist presence in American literature that became the core of her influential volume, Playing in the Dark.”26