Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

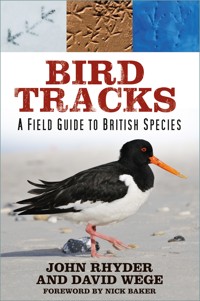

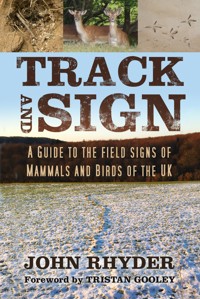

'Never have I felt so connected to the natural world than when trailing . . . The direction of the wind is noted almost subconsciously, the alarm calls of birds are obvious and the track and sign of all the other animals, even insects, crossing your trail reveal themselves. It's a strangely peaceful state where every sense seems to be stretched to the limit in a state of extreme concentration, and yet one feels completely relaxed and at peace. The whole of nature is revealed within an animal trail.' John Rhyder explores the world of British mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians through their tracks and other signs, including scat, feeding, damage to trees, dens, beds and nests, providing a fully explained and illustrated guide to the natural world around us. Following years of extensive research from one of the UK's leading wildlife trackers, Track and Sign is illustrated with line drawings and photographs, making identification in the field effective and accurate for both the complete beginner and the expert naturalist.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 247

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2021

Reprinted with amendments, 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, gl50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© John Rhyder, 2021

The right of John Rhyder to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9652 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword

Photo Credits

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Introduction

What is Tracking?

PART 1 TRACKS

Mammal Tracks

Gaits and Track Patterns

Bird Tracks

Reptile and Amphibian Tracks

Invertebrate Tracks

PART 2 SIGN

Scat

Signs on Trees and Plants

Signs on Nuts, Seeds, Fruit and Fungi

Holes, Nests and Paths

Scrapes, Digs and Couches

Predation, Chews and Remains

Selected Bibliography

Glossary

FOREWORD

Time in the field with John Rhyder always inspires me. We have a habit of looking at different things, but this is what is so enjoyable. John’s observations remind me how much more there always is to discover.

Outdoor specialists learn certain instincts. We learn to spot the signs within our field without hesitation. In my area of natural navigation, I recognise the key shapes and patterns within trees, constellations and clouds, for example. After many years, these observations become automatic.

This approach works in all other fields too. The patterns vary, but experience makes them leap out and it’s always a joy to witness. John sees the movement of a deer in the angle of leaves – he can’t help it.

There is another instinct that experts develop – a sense for those who are born to share these skills. It is so exciting when someone pushes their knowledge to the point where their expertise becomes an art form. But teaching is not the same as doing; experts only make good authors if they keep sight of the path they followed.

There are some who profess a mysterious ability that can’t be explained. These aren’t the best people to learn from. Expertise is a journey that starts by spotting the same simple patterns, repeatedly. Great teachers don’t claim strange powers, they show you the patterns. John does not claim a mystical provenance for his skills. He explains how he gained his insights and values the work of others, especially the CyberTracker approach. But he has gone on to develop these skills in his own way.

This is what makes John’s work so refreshing and valuable; he shares his extensive experience, but never abandons the path he followed. He shows us the patterns that are worth looking for and invents none. It is a rare approach, one that teaches us how to see what is really there.

Tristan Gooley

PHOTO CREDITS

I have had a good deal of support from the tracking community in Europe to compile the images for this book. I have credited these contributors by using their initials after each image, as can be seen below. Any images not highlighted in this way, together with all the line drawings, are the work of the author.

In alphabetical order:

BO

Beke Olbers

BM

Brian McConnell

CB-R

Caron Buckingham-Rhyder

CP

Cris Palmares

DP

Dan Puplett

DC

Dave Crosbie

DM

David Moskowitz

DW

David Wege

EL

Ed Ledesma

GH

Graham Hunt

IM

Immo Meyer

JK

Jörn Kaufhold

KC

Kim Cabrera

LE

Lea Eyre

MB

Matt Binstead

RH

Rebecca Hosking

RN

René Nauta

RA

Richard Andrews

RB

Rob Brumfitt

SM

Sally Mitchell

SR

Simone Roters

TB

Thomas Baffault

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In addition to everyone mentioned above who donated photographs allowing the completion of this work, I would especially like to thank the CyberTracker community of evaluators in North America, who have tracked, trained and worked with me to make me a better tracker and naturalist. In no particular order, they are Nate Harvey, Brian McConnel, Marl Elbroch, Casey Mcfarland, David Moskowitz and George Leoniak.

I would especially like to thank the British Wildlife Centre for allowing me access to their animals and David Wege for reading through this before I embarrassed myself too much and sent it to the publishers. Thanks to Louis Liebenberg for the whole concept of CyberTracker and creating such an excellent educational tool.

Thanks, as always, goes to my family for their continued help and support.

A final thank you to this wonderful world and its wildlife that continues to be so fascinating.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Rhyder is a naturalist, wildlife tracker and woodsman and is certified through CyberTracker Conservation as a Senior Tracker. This involves being evaluated and scoring 100 per cent at Specialist level in both track and sign identification and trailing or following the animal. He is the first person in Northern Europe to become a Senior Tracker. John is also an evaluator for the CyberTracker assessment system.

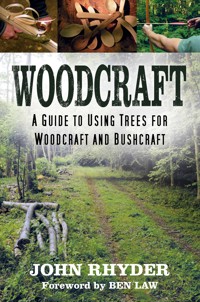

He is fascinated by the natural world and the skills and knowledge that support our interaction with it. John writes and teaches about natural history, wildlife, tracking, ethnobotany and bushcraft.

INTRODUCTION

Track and Sign covers the main sign left behind by mammals – at least those that don’t fly – and those birds that commonly leave tracks. I have included lots of illustrations but have limited any explanations to those that specifically explain the track and sign and why it might be there.

Understanding animal behaviour is a crucial part of becoming a great tracker, but the status and distribution of wildlife and a myriad of other details lie outside the scope of this book. I have also included track and sign of reptiles and amphibians and some insects, especially where these are commonly encountered. Both of these subjects could form tracking studies in their own right and so I talk about their tracks in very general terms. However, if a tracker stares at the ground for long enough they will come across this sign, so a ballpark idea of what it might be will be useful.

Much of the subject matter of this work is, I hope, fairly new and not widely known. It has stemmed from my involvement in the world of CyberTracker, and discovering the level of detail it is possible to pull from tracks on the landscape since meeting up with some remarkable trackers involved in this system.

I have set out the sections on sign in what I believe to be a logical fashion to aid the tracker in the field. As such, they are variously titled scats, damage to fungi, trees and plants, digs and scrapes, etc. This as opposed to listing every piece of sign left by each individual species, so hopefully the tracker can jump straight to the relevant section and start looking.

Tracks are explained in detail and each has a photo or several photos. I have tried to include, where possible, both the perfect track and examples of ones that are more frequently encountered, those that may be a bit smeared or incomplete. The tracks are arranged in family groups which have similar features.

There is a companion volume to this book which just contains the track drawings and can also be taken out into the field independently. It is designed to be laid alongside a track for a direct comparison and hopefully identification.

In addition to wild animals, I have also included the main domestic species found in our landscape. It is not unusual to encounter the tracks of alpaca in the woods as people organise walks with these creatures. Equally, it is not unusual to come across the sign of cattle and ponies in remote locations as the process of ecosystem restoration becomes more widespread. There are one or two exotics included, which may or may not establish in our landscape in the future.

John Rhyder, March 2020www.woodcraftschool.co.uk

WHAT IS TRACKING?

According to the great South African tracker Louis Liebenberg, tracking may well be the origin of scientific thought and methodology. The premise for Louis’s theory is that in order to track an animal to the extent that one may find it, one must first hypothesise as to where the animal is likely to be, and then use the tracks and sign to confirm that the animal’s whereabouts are as first suspected. Should further evidence from the track and sign indicate that the tracker’s original idea was wrong, then a new hypothesis must be formed using this new information gathered from the actual process of tracking that animal. In short, the tracker imagines or hypothesises where the animal might be found and uses the tracks to either prove or disprove this theory.

Tracking an animal therefore becomes a two-stage process. Firstly, identification of track and sign; and secondly, using those tracks and sign in conjunction with a sound theory to follow and find the animal. This second stage in the process is trailing. These two aspects of the subject can be treated separately, and indeed many trackers become proficient at only track and sign identification, even to a professional level. They may or may not explore the possibilities that trailing has to offer. The two aspects are two sides of the same coin and work hand in hand with each other, although this book deals exclusively with track and sign.

THE CYBERTRACKER SYSTEM

As an advocate of traditional ecological knowledge, Louis Liebenberg was very aware of the loss of knowledge from indigenous peoples across his native Africa. In tracking, Louis saw a perfect application for the astounding natural history knowledge many of these people still possessed, using it for wildlife survey and monitoring. With this in mind, he developed an icon-driven data capturing program. This meant that regardless of the user’s level of literacy, local people could enter the Bush, find wildlife track and sign, tap the icon corresponding with that species, and then have all that data automatically uploaded onto a GPS. This is the ‘cyber’ element of the CyberTracker system.

The reliability of using this system, however, can be undermined should the person gathering the information not be a reliable tracker. To combat this, Louis developed an evaluation process to objectively test observer reliability. The resulting CyberTracker evaluation system is split into two distinct areas: Track & Sign, and Trailing, each of which is further divided into Standard- and Specialist-level evaluations that are scored as follows.

TRACK AND SIGN EVALUATION

TRACK & SIGN I

The candidate must be able to interpret the track and sign of medium to large animals and must have a fair knowledge of animal behaviour. To qualify for the Track & Sign Level I certificate, the candidate must obtain 69 per cent on the Track & Sign Interpretation evaluation.

TRACK & SIGN II

The candidate must be able to interpret the track and sign of small to large animals, interpret less distinct sign, and must have a good knowledge of animal behaviour. To qualify for the Track & Sign II certificate, the candidate must obtain 80 per cent on the Track & Sign Interpretation evaluation.

TRACK & SIGN III AND IV

The candidate must be able to interpret the track and sign of any animal, interpret obscure sign, and must have a very good knowledge of animal behaviour. To qualify for the Track & Sign III certificate, the candidate must obtain 90 per cent on the Track & Sign Interpretation evaluation, and for Level IV, 100 per cent.

TRACK & SIGN SPECIALIST CERTIFICATE

The candidate must be able to interpret the track and sign of any animal, interpret very obscure sign, and must have an excellent knowledge of animal behaviour. To qualify for the Track & Sign Specialist certificate, the candidate must obtain 100 per cent on a Track & Sign Interpretation Specialist evaluation.

TRACK & SIGN SPECIALIST EVALUATION

The process during the Track & Sign Specialist evaluation is identical to the above-described evaluations, except for the following variation. At least fifty very difficult Track & Sign questions will be asked, along with no more than ten difficult questions. No easy Track & Sign questions will be asked. In addition to this, seven extremely difficult Track & Sign questions will be asked.

No penalty is awarded for an incorrect answer on an extremely difficult question, but three correctly answered extremely difficult Track & Sign questions cancel the mistake of one incorrect answer. Thus, participants can rectify up to two mistakes during an evaluation and still earn their Specialist certificates.

TRAILING EVALUATION

TRAILING I

The candidate must be a fair, systematic tracker and be able to track humans or large animals. He or she must have a fair ability to judge the age of sign. To qualify for the Trailing I certificate, the candidate must obtain 70 per cent on the trailing of a human or large mammal spoor.

TRAILING II

The candidate must be a good, systematic tracker and be able to track large animals. He or she must have a fair ability to judge the age of sign. To qualify for the Trailing II certificate, the candidate must obtain 80 per cent on the trailing of a large mammal.

TRAILING III AND IV

The candidate must be a good, systematic tracker and be able to track medium or large animals. He or she must have a fair ability to judge the age of spoor. To qualify for the Trailing III certificate, the candidate must obtain 90 per cent on the trailing of medium or large mammal spoor. To qualify for the Trailing IV certificate, the candidate must obtain 100 per cent on the trailing of a medium or large mammal.

TRAILING SPECIALIST CERTIFICATE

The Trailing Specialist evaluation is done in varying (easy, difficult and very difficult) terrain on an animal that is difficult to follow, and must be conducted by both an evaluator and an external evaluator.

The candidate must be a good, speculative tracker. This includes the ability to predict where spoor will be found beyond the vicinity directly ahead of the tracker. He or she must be good at judging the age of spoor and must be able to detect signs of stress, or the location of carcasses from spoor. The Trailing Specialist must obtain 100 per cent on the trailing of a difficult animal trail.

CYBERTRACKER IN THE NORTHERN HEMISPHERE

The CyberTracker system rapidly grew in popularity across southern Africa and soon came to the attention of Mark Elbroch, an American tracker, author, biologist and mountain lion researcher. Mark travelled to Africa to learn the system directly from Louis, and together they brought it to America.

It wasn’t long before Mark’s work became known in Europe, and Mark was approached to come to the UK to establish the system here and in the rest of northern Europe. The first evaluations in the UK were held in 2012 at Woodcraft School and Woodsmoke. On these evaluations were two other trackers, soon to become important figures in European wildlife tracking: René Nauta, of The Netherlands, and Joscha Grolms from Germany, both of whom, together with myself, are now evaluators in the CyberTracker system.

Together with our American colleagues, the three of us have worked hard at finding the same standard and level of detail in tracking and trailing information that is available in South Africa and North America. Inspired by the level of detail we were shown by our American colleagues, and immediately after the first evaluation in the UK, we realised there could be much more detail in the information and literature available to European trackers. With this in mind, I began to run captive animals across ink and other substrates to separate some of our more closely related species and to pull as much detail from the tracks as possible.

Following on from this, Joscha and René have also conducted their own research using similar methods. So much so that we are now confident that this, and the work of René and Joscha, offer something significant and new to European tracking.

While North American trackers were instrumental in establishing CyberTracker in northern Europe, trackers from Africa were working with some excellent people in the south of our continent, most notably José Galán of Spain, also a CyberTracker evaluator. It is therefore now possible to explore and use CyberTracker standards across the whole of Europe.

USES OF TRACKING AND TRAILING

It is fair to say that tracking is underused in our region of the world. It has become the preserve of enthusiastic amateurs and is not always given the general credibility it deserves as a serious tool for the field naturalist. While track and sign may not entirely replace modern techniques of wildlife monitoring, it can certainly augment them, and may in some instances be superior.

Consider the amount of ground a trained tracker can cover versus the number of camera traps that may have to be deployed to get the same kind of coverage. When looking at it in this way, it is clearly cost-effective to train trackers to a high standard to ensure observer reliability.

This makes tracking an ideal, if not necessary, tool in the armoury of today’s competent field naturalist. It is especially useful in detecting the presence or absence of unusual or difficult to observe species. It can also be used to estimate population densities. Furthermore, track and sign can establish the location of regularly used travel routes, which, in turn, may inform the placement of such things as badger gates and underpasses when considering new road and rail developments.

Coupled with modern techniques such as GPS collars or camera traps, more information can be gathered than by simply using the technology alone. Recently, I had the pleasure to accompany Mark Elbroch and his team in Washington State, USA, as they visited mountain lion GPS clusters. These are indications given off by the radio-collared mountain lions in Mark’s study group.

The cluster refers to multiple GPS signals that have been fairly static or ‘clustered’ around a location for a time period of perhaps a day or two. Usually, this would indicate that the animals have made a kill and have been feeding.

Using telemetry, the kill site can be homed in on, and then the various mountain lion trails coming and going can be followed using tracking skills to gather extra information. This includes information on the kill itself, its status and the species preyed upon. It can also show what else has been feeding there. Trails may lead to latrine sites, allowing the possibility of DNA sampling and, as not all the animals are likely to be collared, this approach to surveying can indicate the number of individuals around the kill site.

In conjunction with technology, tracking may also inform the tracker as to the best possible place to aim trail cameras to increase the chance of catching the target on film.

In the UK, specialist knowledge of the tracks of protected species, and those species likely to be confused with them, is a must for any ecologist working in this field. In the world of forestry, deer numbers are at a level possibly greater than at any time in our history. Recognition of deer sign and the ability to separate sign of the various species and then to separate that sign from any other animal can only add to the effectiveness of programmes designed to control deer damage.

Recreationally, tracking is a wonderful skill to learn for the amateur naturalist, enhancing any walk in the countryside. For the photographer, it can put you in just the right spot for that winning image, and as with many of forms of nature connection, tracking can effectively enhance wellbeing. Tracking can also be used in tackling wildlife crime and assisting in search and rescue.

The author’s view from a mountain lion bed in Washington State, USA.

As a fundamental part of who we are as human beings, it touches something deep within the psyche. In all the things I have done in my outdoor career, never have I felt so connected to the natural world than when trailing. When I track well, it becomes intensely absorbing in the same way as I hear people describe flow states and mindfulness. In these moments, the trail reveals itself, stretching into the distance. The direction of the wind is noted almost subconsciously, the alarm calls of birds are obvious and the track and sign of all the other animals, even insects, crossing your trail reveal themselves. It’s a strangely peaceful state where every sense seems to be stretched to the limit in a state of extreme concentration, and yet one feels completely relaxed and at peace. The whole of nature is revealed within an animal trail.

PART 1

TRACKS

MAMMAL TRACKS

FOOT MORPHOLOGY

Eons ago, all that existed mammal-wise was a primitive, five-toed shrew-like creature from which all mammals have descended. This creature had hands and feet arranged in a way that differed very little to the present day. This arrangement is typically five toes on both front and rear feet, with toe pads to protect the delicate tips of the toe bones, palm pads to protect the joints at the other end of these delicate bones and, in the case of the front feet, carpal pads to protect the bones of the wrist. Within this group, especially with the smaller animals, the palm pads are often separate, forming individual cushions. The toes are numbered one to five, counting from the inside, with toe number one being the equivalent of the human thumb on the front, or big toe on the rear. The lagomorphs – rabbits and hares – don’t have pads as such, but instead their delicate bones are protected by a mat of stiff fur. In these tracks, often only the claws will show.

The front right track of a mink, a plantigrade animal. Note how the palm pads are separate cushions. The toes are numbered one to five starting from the inside or the equivalent of our thumb.

The original shrew-like mammals walked in a flat-footed fashion, with most of the sole of the foot capable of making contact with the ground. These sole-walkers, or plantigrade animals, are still with us today, and in the UK include the following groups: insectivores; mustelids; rodents; lagomorphs; and primates including us humans.

Some species of plantigrades still have five toes on the front foot and five on the rear. In particular, the mustelids and insectivores (and humans). Some, however, the rodents and lagomorphs (rabbits and hares), have lost one of the toes. In the case of rodents, many have lost the thumb (toe number one) on the front foot, and the lagomorphs have lost the big toe on the rear foot. However, there may be a vestigial impression of the thumb in the front track of some rodents, but it’s so insignificant we can largely ignore it for identifi-cation purposes. Even in the species that still have five toes present on their front feet, the thumb often doesn’t show well, or indeed at all, in the track.

Walking flat-footed is a relatively slow form of locomotion, although some plantigrade animals can really move if they have to. Just imagine trying to outrun a charging (plantigrade) brown bear!

Look closely at the bottom left track of this set of four. The vestigial toe one of this grey squirrel is just visible on the edge of the inside carpal pad.

The vestigial toe can be seen in the (right front) foot of this grey squirrel.

Separate pads are visible on the rear foot of this yellow-necked mouse.

The next foot type belongs to the groups of animals moving primarily on the tips of their digits. These we called digitigrades, or finger walkers to keep it simple. Their feet are arranged with toe pads protecting the ends of the finger bones, and palm pads protecting the toe joints at the other end of these, but in contrast to the plantigrades these pads are fused together into one large structure.

The carpal pad can still be found on the front foot of digitigrades, but because these animals are up on their toes, this pad is now high up the leg. It will show in the track only if the substrate is very deep and occasionally if the animal jumps from a height.

Note how the carpal pad shows on this cat track, the animal having jumped down from a height. You can also see a hint of some of the claws.

In our region we have feline, canine and vulpine animals representing the digitigrades. These species generally have five toes on the front foot and four on the rear, but toe number one on the front track is represented by the dew claw, which will only register in deep substrate or if the animal is moving really fast. Some breeds of domestic animals show five toes in both their front and rear tracks.

Often the tracks of digitigrades register most deeply with the toes, and less so with the palm pad. Essentially, these animals have tilted forwards onto their toes for speed, and when they move flat out on hard ground the tracks may not show palm pads at all.

The blunt claws of canines are there for digging but may also be used for increased traction, just like running spikes. At high speeds, and on some substrates, only the claws of dogs may show.

On hard substrates, only the claws of dogs may show.

This dog came to a sudden stop, revealing its carpal pads and dew claws.

The final mammal foot type is found in the unguligrades, or ungulates, that have a toe pad equivalent to our own fingertip, but with a vastly modified nail (or hoof) which they are effectively walking on. We can call them nail-walkers or cloven-footed animals.

With the exception of the horse, all the representatives of this group in our region are walking on the nails of toes three and four. Horses walk on the end of toe three, although there has been some fusion of other digits over the eons and so it’s not quite as simple as this. In some other countries there are more odd-toed ungulates than we have, for example rhinos have three toes on each foot.

Aside from horses and their like, our ungulate fauna comprises cows, sheep, goats, pigs and wild boar, and six species of deer (seven including reindeer). Also, increasingly regular in our landscape are more exotic creatures such as alpaca.

All of these species have lost toe one altogether, in terms of it registering in the track. Toes two and five are much reduced in size and higher up the leg and, as with dogs and cats, are referred to as dew claws. These may register reliably in the track in the case of pigs, or only in deep substrate or at high speeds in the case of deer.

The toe pads of ungulates register in their tracks with differing regularity between species, to the extent that its presence, size and shape can be diagnostic in identification. The underside of the modified nail (the hoof) is hollow and called the subunguis. The hoof wall, or unguis, is a major component of the track itself, forming much of the detail and shape produced on the ground, and frequently the deepest part of the track. These animals are called ungulates because they walk on their unguis.

These evolutionary adaptations are largely accepted as being driven by speed: plantigrades being relatively slow moving compared with animals that stand on their toes, which, in turn, are slower than animals that are now high up on their nails.

This goat track shows the elements of an ungulate track most commonly encountered.

These are the rear and front tracks of a roe deer. It was moving reasonably quickly over soft substrate and so the dew claws (toes two and five) are showing. Note the angle and position of these relative to the rest of the track to identify front and rear.

NB: there are several photographs of various animal feet further along in this book.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN A TRACK

There are several components of a track that should be considered when trying to get to grips with smudges and holes in the mud and discerning their ownership. The process outlined here will become subconscious after a while as you build up more experience. Just as you can probably look at a cow and say immediately, ‘That’s a cow’, and probably just as easily see a leg, an udder or an ear and still be fairly happy it’s a cow, you will develop this ‘one-glance’ skill with tracks if you persevere.

This ‘fast-thinking’ approach will make you a much better or, should I say, more effective tracker. For more information on fast thinking, read Tristan Gooley’s (2018) book Wild Signs and Star Paths.