Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

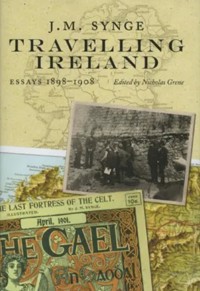

Synge's topographical essays appear here in their original newspaper and periodical publication form, taken from the Manchester Guardian, The Gael and The Shanachie, complete with illustrations, mostly by Jack B. Yeats. A substantial essay-introduction by Nicholas Grene places his work in its historical context (1898-1908) and evokes the man and his milieu. Synge's writings explore social, political and aesthetic perspectives gained from his travels on the Atlantic seaboard and among the Wicklow Hills. Eighteen of them concern the Aran Islands and the west of Ireland of the Congested Districts, from County Donegal down to Galway, describing famine relief projects, ferrymen, kelp gatherers, boat-builders, peasant proprietors, small shopkeepers, races and fairs. Nine deal with County Wicklow and West Kerry, their vagrants, landlords and pastimes. Maps, photographs by Synge, facsimile title-pages, and above all Jack Yeats' inimitable drawings, embellish the text.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

J. M. SYNGE

TRAVELLING IRELAND

ESSAYS 1898–1908

Edited by Nicholas Grene

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

Contents

Title Page

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Introduction

Note on the Text

ESSAYS

‘A Story from Inishmaan’ (1898)

‘The Last Fortress of the Celt’ (1901)

‘An Autumn Night in the Hills’ (1903)

‘A Dream of Inishmaan’ (1903)

‘An Impression of Aran’ (1905)

‘The Oppression of the Hills’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: From Galway to Gorumna’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: Between the Bays of Carraroe’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: Among the Relief Works’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: The Ferryman of Dinish Island’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: The Kelp Makers’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: The Boat-Builders’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: The Homes of the Harvestmen’ (1905)

In the “Congested Districts”: The Smaller Peasant Proprietors’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: Erris’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: The Inner Lands of Mayo – The Village Shop’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: The Small Town’ (1905)

‘In the “Congested Districts”: Possible Remedies – Concluding Article’ (1905)

‘The Vagrants of Wicklow’ (1906)

‘The People of the Glens’ (1907)

‘At a Wicklow Fair: the Place and the People’ (1907)

‘A Landlord’s Garden in County Wicklow’ (1907)

‘In West Kerry’ (1907)

‘In West Kerry: the Blasket Islands’ (1907)

‘In West Kerry: to Puck Fair’ (1907)

[‘In West Kerry: at the Races’ (1910)]

‘In Wicklow: On the Road’ (1908)

Bibliography

Copyright

Illustrations

Map of Ireland (Photographic Centre, Trinity College Dublin)ii

Map of Wicklow (reproduced from Ann Saddlemyer (ed.), Letters to Molly: John Millington Synge to Maire O’Neill (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971)xvi

Margaret and Pegeen Harris, Coolnaharrigle, Mountain Stage, Co. Kerry (photo by Synge)xx

Map of Connemara (reproduced from Mecredy’s Road Map of Connemara for Tourists and Cyclists, Glucksman Map Library, Trinity College Dublin)xxv

Rail map of Ireland (reproduced from Michael Baker, Irish Railways Past and Present, Volume I (Peterborough: Past and Present Publishing, 1995)xxviii

Map of Kerry railways (reproduced from John O’Donoghue, The Sunny Side of Ireland, as Viewed from the Great Southern and Western Railways (Dublin: Alex Thom, [1898])xxix

Title-page of The Gael.xxxv

‘The Last Fortress of the Celt’, The Gael, April 1901.xxxvii

Title-page of The Green Sheaf.xxxix

Title-page of The Shanachie.xliii

Spinning girls (photo by Synge, Paris)13

Launching the curraghs (photo by Synge, Paris)14

The fishermen’s return (photo by Synge, Paris)16

Going for turf (photo by Synge, Paris)18

‘You’ve come on a bad day’, said the old woman (M. O’Flaherty)24

Near Castelloe, Co. Galway, (Jack B. Yeats)*40

[The Poorest Parish]: Connemara Mare and Foal (Jack B. Yeats)45

A Man of Carraroe (Jack B. Yeats)49

Relief Work (Jack B. Yeats)50

The Causeway of Lettermore (Jack B. Yeats)54

The Dinish Ferryman (Jack B. Yeats)55

Gathering Seaweed for Kelp (Jack B. Yeats)60

Kelp-Burning (Jack B. Yeats)64

Boat Building at Carna (Jack B. Yeats)65

A Cottage on Mullet Peninsula (Jack B. Yeats)70

Outside Belmullet (Jack B. Yeats)75

Belmullet (Jack B. Yeats)80

The Village Shop (Jack B. Yeats)85

Mayo Fair (Jack B. Yeats)90

The Emigrant (Jack B. Yeats)95

The Tinker (Jack B. Yeats)106

* The titles given for the Jack B. Yeats drawings here are taken from the definitive catalogue in Hilary Pyle, The Different Worlds of Jack B. Yeats (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1994), pp. 129–33. The illustrations to the Manchester Guardian articles were without captions.

Acknowledgments

The drawings of Jack B. Yeats used as illustrations for the essays ‘In the Congested Districts’ and ‘The Vagrants of Wicklow’ appear by permission of DACS on behalf of the Estate of Jack B. Yeats; the photographs by Synge are reproduced courtesy of the Board of Trinity College Dublin. The book would not have been possible without the financial support of the School of English, Trinity College, The Provost’s Academic Development Fund, and the Trinity Association and Trust, which is gratefully acknowledged.

I owe a special debt of thanks to Emilie Pine, who typed the whole text, and to Sophia Grene, who provided copies of the original articles from The Manchester Guardian. In the sourcing and preparation of the illustrations, I acknowledge gratefully the help of the staff of the National Library of Ireland; within Trinity College I have to thank the Library staff of the Manuscripts and Early Printed Books Departments, Paul Ferguson of the Glucksman Map Library, Brendan Dempsey and Brian McGovern of the Photographic Centre, and, for the recovery of otherwise inaccessible audiotaped material, Martin Murphy of Audio-Visual and Media Services. Elaine Maddock of the School of English gave endless and endlessly patient technical support. For the provision of all sorts of information which I could have found in no other way, I want to thank Aidan Arrowsmith, Angela Bourke, David Fitzpatrick, Muiris Mac Conghail, Cormac Ó Gráda and Hilary Pyle. I am especially grateful to Eamon Ó Fiachán and Pat O’Shea, grandson and great-grandson of Philly and Margaret Harris, Synge’s hosts in Mountain Stage, for the benefit of family memories of his visits. I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my colleague Paul Delaney for his generosity and care in reading my whole manuscript so meticulously. The mistakes that remain are none of his fault. As always, I have benefited from the advice, judgment and help of my wife Eleanor, not to mention the pleasure of her company on our joint tour of Synge sites in the West of Ireland. I am grateful to Antony Farrell of Lilliput Press for agreeing to publish the book and seeing it through to completion.

Abbreviations

CL I–II John Millington Synge, Collected Letters, ed. Ann Saddlemyer (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983), 2 vols.

CW I–IV J.M. Synge, Collected Works, general editor Robin Skelton (London: Oxford University Press, 1962–8) 4 vols:

I Poems, ed. Robin Skelton (1962)

II Prose, ed. Alan Price (1966)

III Plays: Book 1, ed. Ann Saddlemyer (1968)

IV Plays: Book 2, ed. Ann Saddlemyer (1968)

Greene & Stephens David H. Greene and Edward M. Stephens, J.M. Synge1871–1909 (New York: Collier, 1961 [1959])

Hannigan & Nolan Ken Hannigan and William Nolan (eds), Wicklow: History and Society (Dublin: Geography Publications, 1994)

Interpreting Synge Nicholas Grene (ed.), Interpreting Synge: Essays from the Synge Summer School 1991–2000 (Dublin: Lilliput, 2000)

Mc CormackW.J. Mc Cormack, Fool of the Family: A Life of J.M. Synge (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000)

Micks W.L. Micks, An Account of the Constitution, Administration and Dissolution of the Congested Districts Board for Ireland from 1891 to 1923 (Dublin: Easons, 1925)

Ó Muirithe Diarmaid Ó Muirithe, A Dictionary of Anglo-Irish (Dublin: Four Courts, 1996)

Introduction

In the ‘Preface’ to Synge and the Ireland of His Time, W.B. Yeats tells how he consoled himself during his friend’s final illness with the thought that at least Synge ‘would leave to the world nothing to be wished away – nothing that was not beautiful or powerful in itself, or necessary as an expression of his life and thought’.1 The Preface goes on to explain why Synge and theIreland of His Time was appearing as a separate pamphlet rather than as the Introduction to the four-volume Works of John M. Synge, published by Maunsel in 1910. Yeats had quarelled bitterly with the publisher George Roberts over the decision to include in the Works the twelve essays, ‘In the “Congested Districts”’, published in the Manchester Guardian in 1905. For Yeats this inferior journalistic writing was not worthy of the Synge canon, but something to ‘be wished away’.

With the authority of Synge’s executors apparently behind him, Roberts had won the day in this argument. The fourth volume of the 1910 Works had duly appeared with the somewhat awkward subtitle: ‘In Wicklow, In West Kerry, In the Congested Districts and Under Ether,’ the latter a previously unpublished piece Synge had written about his experience of undergoing his first operation under general anaesthesia. In 1911, however, the topographical essays were collected as In Wicklow, West Kerry and Connemara with eight newly commissioned drawings by Jack Yeats, to match those that illustrated The Aran Islands as originally published in 1907, and this was to become the received form of Synge’s travel writings. Although Roberts and Yeats were initially at odds over the issue of literary standards, they were both concerned to compose Synge’s work into a monumental completed oeuvre. The invented title In Wicklow,West Kerry and Connemara brings together three picturesque areas of rural Ireland into a resonantly rhythmic and alliterative cadence. North Mayo, one of the less famously scenic of the Congested Districts observed is omitted, as is the term ‘congested districts’ itself, with all its associations of political and social issues. The travel writings are aestheticized and removed from their historical contexts.

The aim of this edition is to re-historicize them. Yeats wanted within the Works nothing that was not ‘beautiful or powerful in itself’; Roberts in publishing In Wicklow,WestKerry and Connemara sought to produce another book to complement The Aran Islands and the plays by which Synge had won his fame. My aim, by contrast, is to return to the original writings of the literary journalist who was still struggling to get published, who wrote and re-wrote his reflections in Ireland for whatever journals or newspapers could be persuaded to take them. In place of a travel book organized by area,2 the original texts of the essays published in his lifetime are here arranged in the chronological order of their publication. Synge andthe Ireland of His Time was an attempt by Yeats to conjure up a specifically Yeatsian vision of the Ireland of Synge’s time. This edition looks to situate the travel essays within an Edwardian Ireland rather different from that of the Yeatsian or even the Syngean imagination. I want to include some of the features of that period which Synge may have chosen to omit or occlude. This is not done out of either pedantry or perversity. Rather, I hope to provide a context for Synge’s travel essays – the places he went to, the forms of transport he used to get there, the journals and newspapers in which he published – that may help us better to understand both Synge and the Ireland of his time.

Destinations

John Millington Synge was a city-dweller. Born in Rathfarnham near Dublin in 1871, the son of a barrister who died when he was only a baby, he lived almost all his life with his widowed mother in one Dublin suburb or another, apart from some time in Germany (1893–5) shortly after graduating from Trinity College, and a series of winters in Paris (1895–1902). When he became a founding Director of the Abbey Theatre in 1905, he was the only one of the theatre’s ruling triumvirate actually resident in Dublin: Lady Gregory lived in Coole Park, County Galway, W.B. Yeats was based in London. The Synge family, however, was only one generation removed from land and landownership. Synge’s grandfather had held large estates in Wicklow, and when the writer was a boy, his uncle, Francis Synge, still occupied the grand Georgian castle of Glanmore. Synge was thinking of his own family situation when, contemplating ‘A Landlord’s Garden in County Wicklow’, he remarked that ‘many of the descendents of these people have … drifted in professional life into Dublin, or have gone abroad’. One of John’s older brothers was a landagent, another an engineer working in Argentina, a third a medical missionary in China; his sister had married a lawyer. To some extent, still, they thought of themselves as the Synges of Wicklow, and it was close to Glanmore and the village of Annamoe that Mrs Synge, the playwright’s mother, rented holiday homes for the months of summer from 1890 on.

Map of Wicklow

For Synge to travel to Wicklow each summer was to return to familiar territory, but also to escape from the city. He participated in the country pastimes of his family, typical enough of their class; he fished, walked and cycled with his brothers. If he did not shoot with his brother-in-law Harry Stephens, he accompanied him on the outing to retrieve a wounded gun-dog, the incident that provided the basis for ‘An Autumn Night in the Hills’. It is noticeable, however, that in the essay the brother-in-law is suppressed altogether, and the journey to Glenmalure (which was actually a family affair involving two outside cars, Synge’s mother, sister, niece and nephews) is turned into a solitary walking expedition into the mountains.3 Instead of the sinister return alone through the darkening valley portrayed in the essay, Synge had ended the actual day in question fishing with Stephens, and taking table d’hôte in the Glenmalure Hotel.4 Synge, as family dissident, nationalist in politics, freethinker in religion, saw Wicklow differently from the people of his class and background. His self-consciously Wordsworthian poem ‘Prelude’, for instance, has no place for social setting. It represents instead a flight from human contact towards an unmediated intercourse with nature:

Still south I went and west and south again,

Through Wicklow from the morning till the night,

And far from cities, and the sites of men,

Lived with the sunshine and the moon’s delight.

I knew the stars, the flowers, and the birds,

The grey and wintry skies of many glens,

And did but half remember human words,

In converse with the mountains, moors, and fens. (CW I 32)

The push in Synge’s travels was towards edges, peripheries, away not only from Dublin but from the socio-political contexts in which he, by virtue of being one of the Synges of Wicklow, was implicated. He sought those least modernized, least Anglicized remotenesses of Ireland in which people lived on frontiers of the natural world.

Wicklow itself was curiously anomalous in this. Its wild mountainous terrain made it one of the last strongholds of native Irish resistance to English rule. Still in the late sixteenth century a traditional chieftain like Feagh MacHugh O’Byrne could hold out against the colonial forces of the English, and inflict repeated defeat on the forces of Lord Deputy Gray, to the indignation of Spenser in his View of the State of Ireland.5 Wicklow, known throughout this period only as the ‘O’Byrne country’, was the last county to be assimilated into the standard English administrative system when it was shired in 1606.6 But, so close as it was to Dublin, by the eighteenth century it had become a favourite site for gentleman’s residences, landed estates with fine houses and picturesque views owned by aristocrats such as the Fitzwilliams, who had huge properties elsewhere, or people, like the Synges themselves, who had made their money in the city and invested in land as a sign of status. This upper-class recreational aspect to Wicklow became a mass phenomenon in the nineteenth century when its beauty-spots, Glendalough, the Meeting of the Waters – made famous by one of Thomas Moore’s ‘Irish Melodies’–drew regular crowds of day-trippers from Dublin. It is from this time that the county acquired its tourist soubriquet of the ‘Garden of Ireland’. Yet still there were mountains and wild glens beyond the tourist trail, and it is to these empty spaces and the sparse population that inhabited them that Synge was drawn. In the Wicklow essays it is such a territory that he contemplates, a territory beyond the tenanted social landscape of his own family, a natural world on the margins of the processes of history.

If Wicklow was one sort of marginal space for Synge, in spite of its proximity to Dublin, Aran as islands off the west coast of the western island of Ireland represented some sort of ultimate extremity. ‘It gave me a moment of exquisite satisfaction,’ commented Synge in The Aran Islands on his first curragh journey from Aranmore, the largest of the islands, to Inishmaan, ‘to find myself moving away from civilisation in this rude canvas canoe of a model that has served primitive races since men first went on the sea’ (CW II 57). He was not by any means the first to have made this trip. The McDonagh cottage on Inishmaan had provided lodgings for many previous visitors when they went to Aran to learn Irish, including Patrick Pearse in 1898, the year of Synge’s own first visit. Antiquarians, anthropologists, folklorists and Celtic scholars had all found materials to interest them in Aran. Yeats and his friend Arthur Symons had visited in 1896, a visit described by Symons in an essay in The Savoy. Yeats was still full of the enthusiasm of that visit when he met Synge for the first time in Paris in December 1896, though it may not have been at this first meeting that he gave the famous advice:

‘Give up Paris … Go to the Aran Islands. Live there as if you were one of the people themselves; express a life that has never found expression’. (CW III 64)

The remote islands of Aran, as a primitive westernmost place, did stand for Synge as some sort of polar opposite to the cultural cosmopolitanism of Paris. And yet they were connected also. Commenting on the story of the Lady O’Connor, told him by the old shanachie Pat Dirane, which provided the basis for his first Aran essay ‘A Story from Inishmaan’, Synge remarked: ‘I listened with a strange feeling of wonder while this illiterate native of a wet rock in the Atlantic, told the same tales that had charmed the Florentines by the Arno.’ To go to these Irish-speaking islands at the very edge of Europe was to return to origins, not only to a pre-colonized Irish culture but to the folk matrix from which European culture itself evolved.

Synge remained faithful to Aran for five years, with month-long visits every summer or autumn from 1898 to 1902, almost always to his favoured Inishmaan. And then in 1903 came a change to Kerry. It was to his brother Robert that he owed the suggestion of staying with Philly and Margaret Harris in Mountain Stage, near Glenbeigh in the south-western county of Kerry: Robert had stayed there when fishing. Again this is a detail that Synge suppresses in his West Kerry essays. No more than in Wicklow does he want his own class persona, his associations with a family that shot and fished, to obtrude into the scenes he is evoking. Kerry became Synge’s holiday destination for successive years from 1903 to 1906. If it was the primitive austerity of Aran that attracted him, it was the colour and strangeness of the county known in Ireland as the ‘Kingdom’. It was here that he gathered many of the experiences that were to enrich The Playboyof the Western World: the vivid language of Michael James and the other inhabitants of his Mayo shebeen; the races on the strand, modelled on the races Synge witnessed in Rossbeigh on 3 September 1906 (CL I 201). For Synge Kerry was a place not only of great natural beauty but of conviviality and of the carnivalesque atmosphere evoked in the races and in Puck Fair, the centre piece of his third ‘In West Kerry’ essay.

Margaret and Pegeen Harris, Coolnaharrigle, Mountain Stage, Co. Kerry

Yet even in Kerry, the remoteness of the islands had a special importance. A disproportionate amount of the West Kerry essays is devoted to the Dingle peninsula, north of Dingle Bay, where he spent time in 1905 and, very briefly and unhappily again in 1907, when he was too ill to stay long. And it is the visit to the Blasket Islands, off the extreme tip of the Dingle peninsula, to which the whole of the second West Kerry essay is devoted. It was a renewal of the feeling he had had in Aran. He wrote in the original Shanachie essay, in a passage omitted from the revised InWicklow, West Kerry and Connemara text, of the emotions he felt on landing on the Great Blasket – ‘the sharp qualm of excitement I always feel when setting foot on one of these little islands where I am to stay for weeks’. It is excitement, but it is also a qualm in the sense of the separation from the ordinary. The stay in the Blaskets was significant as the most intimate experience Synge had of the lives of the people. In the McDonagh cottage where he stayed on Inishmaan and in the Harrises in Mountain Stage also, he had at least his own room. Staying with Pádraig Ó Catháin, the so-called King of the Great Blasket Island, he shared a bedroom with the other men of the house, had to wash and shave in the kitchen, surrounded by the family. This degree of intimacy, his awareness of the physical proximity of Máire Ní Catháin, the young married daughter of the widowed King, whom he calls the ‘little hostess’, and her daily activity running the household, inspired his admiring poem ‘On an Island’:

You’ve plucked a curlew, drawn a hen,

Washed the shirts of seven men,

You’ve stuffed my pillow, stretched the sheet,

And filled the pan to wash your feet,

You’ve cooped the pullets, wound the clock,

And rinsed the young men’s drinking crock;

And now we’ll dance to jigs and reels,

Nailed boots chasing girls’ naked heels,

Until your father’ll start to snore,

And Jude, now you’re married, will stretch on the floor. (CW I 35)

Synge was never to get closer than this to the sense of an Irish domestic interior at its most basic.

Yeats had instructed Synge to go to Aran, ‘to live there as if if you were one of the people themselves’. Someone of Synge’s class and background could never do that: for all his admiration and affection for the people, the self-conscious sense of strangeness permeates all his writing about them. But Synge’s visits to Aran and the Blaskets may have indirectly led on to the islanders themselves coming to ‘express a life that has never found expression’. Only five years after Synge, the Celticist Robin Flower paid his first visit to the Blaskets, the experience he was to evoke in The Western Island.7 Later the classical scholar George Thomson went there also. Between them Flower and Thomson helped to stimulate the production of the island autobiographies of the 1930s which together form some of the most important writing in Irish of the period: Tomás Ó Criomhthain, An tOileánach (The Islandman), 1929, Muiris Ó Súilleabháin, Fiche Blian ag Fás (Twenty Years a’Growing), 1933, and Peig Sayers, Peig, 1936. Synge’s sympathetic vision of the islands from outside provided encouragement to testimony from within those communities, and in the language to which he had at best only partial access.

For students of Irish, for Gaelic revivalists, for national enthusiasts, the western seaboard of Ireland and its remote extremities represented the true spirit of the nation to be visited from the modernized east coast as pilgrimage or retun to origin. From the point of view of the British colonial administration of Ireland, this same area was a chronic and at times acute social and political problem. This was a region of high crime, and common agrarian disturbances. It was in the northwestern county of Mayo that the Land League was formed in 1879 as a concerted grassroots movement to oppose landlord power. The western counties, not coincidentally, were also some of the very poorest in Ireland. In 1891, the year of the fall of Parnell, there was established the Congested Districts Board (CDB) to provide support for the improvement of those areas where the resources available were not sufficient to support the population. In spite of the name, already many of these districts were rapidly being decongested through emigration, and that was one of the issues that the Board was intended to address: how to enable the people to support themselves adequately without having to leave. The CDB invested in the infrastructure of the region, building bridges, harbours and piers, and improved communications. It assisted local fishermen in buying or building boats, and set up local or home industries such as lace-making and knitting. And for the areas over which it had jurisdiction (eventually the whole western seaboard) it was assigned responsibility for land purchase and re-distribution. Instituted by a Conservative administration, it was associated with the politics of constructive unionism by which the government of the time sought to reconcile Irish people to the Union by an amelioration in their social condition.

It is in this context that Synge’s commission to write about the Congested Districts for the Manchester Guardian needs to be placed. He would have seen something of Connemara before on his way to the Aran Islands; he had visited North Mayo in 1904. But the perspective he brought to these areas in June-July 1905 when he visited them with Jack Yeats, who was to act as illustrator for the articles, was bound to be conditioned by the nature of the commission. He was there to investigate conditions in the Congested Districts, to report on what he found: the degree of poverty and deprivation of the people; the success or otherwise of the CDB in the enterprises they had sponsored; the social and demographic trends. While circumspect in his criticism of the CDB, Synge was clearly not in sympathy with its centralized planning strategies, pursued, as he saw it, mechanically and without sensitivity to local conditions. He found Mayo, in particular, disheartening, a desolate landscape of demoralized people, though he tried hard to keep an upbeat tone in at least some of the articles. His overall reaction, in a letter to his friend Stephen McKenna, was suggestive of his mixed feelings:

we pushed into out-of-the-way corners in Mayo and Galway that were more strange and marvellous than anything I’ve dreamed of. Unluckily my commission was to write on the ‘Distress’ so I couldn’t do any thing like what I would have wished to do as an interpretation of the whole thing.

Still, he was exultant at having been paid more than he had ever had before for any journalism, and ‘I’m off to spend my £25.4.0 on the same ground’ (CL I 116) – not in fact, Galway or Mayo but his still preferred Kerry. That impulse to push into out-of-the-way corners, that desire to find there the strange and marvellous in a reality beyond dreaming, this is the spirit that animated Synge’s travelling throughout.

Transport and communications

Synge’s self-image through most of the travel essays is of the lone walker, wandering in desolate places, meeting and talking with the people of communities remote from the modern urban world. There are here conscious elisions, giving a very partial view of the realities on the ground. Synge was in fact very much a man of his own time, taking easily to the new technologies as they became available to him. He bought his first camera from a fellow visitor to Aran in 1898, and later acquired a plate changing Klito, made by Houghtons of London.8 A camera accompanied him throughout his travels, his photographs often used as an important ice-breaker in his meetings with local people, as on the Blaskets, where in fact he may have been the first person to take photographs.9 Synge must also have been among the earliest professional writers to compose directly on a typewriter, a Blickensderfer that he acquired in 1900. Most importantly for his travels in Ireland, he was very much up to date in his use of a bicycle. The 1890s was the great era of cycling, with writers as distant and unlike as Bernard Shaw and Leo Tolstoy learning how to bicycle. By 1895, Synge was already on to his second bicycle, a chain-driven machine with pneumatic tyres, replacing his previous older heavier model. This was a mere seven years after the Irish-based veterinary surgeon John Dunlop had patented the pneumatic tyre, five years since commercial production had begun in Belfast. His cycling is mentioned occasionally in the essays, but Synge rarely alludes to the fact that he brought his bicycle with him on his travels. So, for example, at the opening of his first ‘In West Kerry’ essay, he remarks that at Tralee station ‘I found a boy who carried my bag a couple of hundred yards along the road to an open yard where the light railway starts for the west’. Why would he have needed a boy to carry his bag? Because he would have been pushing his bicycle, recovered from the guard’s van of the Dublin-Tralee train. The bicycle shows up unannounced later in the essay when he is trying to cycle back to Ballyferriter after a night out at the circus in Dingle. This is an anomaly that Synge removed when he revised the text of the Shanachie essay; there is no reference whatsoever to him cycling in the version eventually published in the 1910 Works.

Through the islands and inlets of Connemara there was no way to travel but by hired outside car.

Map of Connemara

This was how Synge and Jack Yeats journeyed through the Congested Districts: a charming Yeats vignette as tailpiece to ‘Among the Relief Works’ shows the two of them sitting behind the driver on the car, as they cross the bridge from Gorumna to Lettermullan. This was such a standard way of observing the countryside that Synge felt called upon to warn in one of the articles against the distorting effect of relying on the carman for information: ‘The car drivers that take one round to isolated places in Ireland seem to be the cause of many of the misleading views that chance visitors take up about the country and the real temperament of the people’. Here, of course, he is claiming the authority of the insider, someone who knows ‘the real temperament of the people’ and is not reliant on the prejudices of the car driver, early twentieth-century equivalent of the cabbie, stand-by of later lazy journalists. The journey from the first part of the Congested Districts tour in Connemara to North Mayo was a real odyssey, as Synge reported to his mother from Belmullet (acknowledging the safe arrival of the parcel she had sent him ‘with pyjamas, and cigarettes’):

We started for here [from Carna] at 11 a.m. with a two hours’ drive to the Clifden line, then we had to train all the way back to Athlone and wait there 5 hours to get the connection for Ballina, so that in the end we reached Ballina at 3 o’clock this morning, then drove here the 40 miles on the long car, in a downpour most of the way, and got here at 10.30. (CL I 113–4)

The two hours on the outside car from Carna on the Galway coast would have taken them inland to Recess, where they could catch the Clifden to Galway train, with a connection at Galway for the main Dublin line to Athlone. They there were able to transfer to the westward line that ran from Athlone out to Killala, getting off at Ballina. The ‘long car’ would have been a descendant of the service originally established by Charles Bianconi to connect first the canal stations and then the railheads with more remote parts of the country.10 This uncovered vehicle, drawn by up to four horses, delivered the post and also carried passengers with six or eight people seated on either side facing outwards with the luggage stacked in between. In ‘The Homes of the Harvestmen’ Synge gives a graphic account of the forty mile journey that took six and a half hours in the pouring rain, delivering the post on the way, changing horses every fifteen miles, though he leaves out the fact that Jack Yeats ‘was so sleepy he had to tie himself on to the car’, as Yeats reported in a letter to John Masefield: ‘When the driver saw me apparently pitching off head foremost he roared with horror but when he saw the rope held he roared with pleasure.’11

It was thus not always easy, and certainly not comfortable, travelling around the more remote parts of Ireland in 1905. All the same, the country had an extended public transport system at that time to which one can only look back with envy from a century later. Steamboat services, subsidized by the CDB, had been introduced in the 1890s from Galway to the Aran Islands, and from Sligo to Belmullet. Railway lines, run by a series of competing companies, crisscrossed the whole country. The connections might not have been too convenient on the Midland Great Western that took Synge and Yeats from Recess to Ballina, but still it was possible to make that journey by train. And the Tralee and Dingle three foot gauge light railway carried Synge on the precipitous thirty-two mile trip across the spine of the Dingle peninsula, with a branch line to the seaside resort of Castle Gregory on the north coast.

The railroads had already developed an advanced tourist industry: this is the fact that Synge most obviously leaves out of his account of the west coast. So, for example, he begins his third West Kerry essay, ‘To Puck Fair’, with a description of the cottage of the Harrises in Mountain Stage: ‘After a long day’s wandering I reached, towards the twilight, a little cottage on the south side of Dingle Bay, where I have often lived. There is no village near it … this cottage is not on the road anywhere – the main road passes a few hundred yards to the west.’ What you would never guess from this is that the cottage was within a very few yards of a railway station, as Margaret Harris explained to him when he first wrote to ask for lodgings with them in 1903.12 Mountain Stage acquired its name because it was a staging post of the old coach road, but from 1891, when the Great Southern and Western had extended its line from Faranfore to Killorglin on to Valentia Harbour, it had its own railway station.

Rail map of Ireland

Map of Kerry railways

What is more, just two stops short of Mountain Stage, Synge could have alighted at Caragh Lake, marked in block capitals on the map as the station for the Great Southern’s sumptuous hotel with all the amenities the fisherman, sportsman or just ‘common or garden tourist’ could want.13 The view of the area given by John O’Donoghue in The Sunny Side of Ireland, as Viewed from the Great Southern and Western Railways is necessarily unlike Synge’s; though the rail tour promoter and the essayist recount the same local mythology of Diarmuid and Grania, it is in markedly different prose styles.14 Synge in his concentration on the traditional lives of the people simply writes out the developed modern infrastructure that had turned such districts into recreational commodities for the urban middle classes.

Synge frequently stressed the isolation of the communities he visits, and this was one of the attractions both of Inishmaan and the Blaskets for him. Yet in both islands he lodged with the postmaster, Patrick McDonagh in Aran, the King Pádraig Ó Catháin on the Great Blasket, and he was never out of reach of the postal service. In one post, he comments in a notebook, letters reached him on the Blaskets from ‘Berlin, the Argentine, Gort, Dublin, and Rathdrum’.15 On that tiny western island, therefore, he could still be in touch with his German translator Max Meyerfeld, his fellow Abbey Director Lady Gregory in Galway, his brother Robert in South America and other family members in Dublin and Wicklow.

Synge tended to stress the disconnection of the island communities from mainstream culture, particularly in the Aran essay ‘The Last Fortress of the Celt’: ‘As a child sees the world only in relation to its own home, so these islanders see everything in relation to their island. Without some such link as Lipton’s Teas, the matters of the outside world do not interest them.’ But the very examples he gives in this passage suggests the opposite. Immediately before this he has commented on the level of concern shown on Aran with the Spanish-American War of 1898, being fought out in Cuba and the Philippines. And their awareness of Lipton’s Teas, alluded to here, that led them to take a partisan interest in the 1899 yachting race for the America’s Cup, in which Sir Thomas Lipton was the British challenger, was not a wholly trivial one either. Within a generation of this time, Lipton had been responsible for transforming tea from a luxury drink to one cheap enough to reach ordinary consumers and thus – for better or worse – producing a radical change in Irish diet. By the 1890s in some areas of the Congested Districts, tea accounted for over 10 per cent of annual household income.16 The old man Synge meets in Gorumna, complaining of the pay on the relief works, puts in significant order the necessaries of life: ‘A shilling a day … would hardly keep a man in tea and sugar and tobacco and a bit of bread to eat.’ It is hardly surprising that the Scottish merchant Lipton, who had so popularized tea by mass advertising as well as cutting its price, and who was sufficiently proud of his Irish roots to call all his racing yachts Shamrock, should have been well known on Aran.

For Synge what made the island communities so significant was their difference. Built in to the legendary advice of Yeats was a contrast between literariness – ‘Give up Paris. You will never create anything by reading Racine’ – and an orality that remained unrepresented in literature – ‘Go to the Aran Islands … express a life that has never found expression’ (CW III 63). But that separateness of the traditional pre-literate society of oral folk culture from the print culture of the outside world turned out to be illusory, as Synge was to find out when he published ‘The Last Fortress of the Celt’ in The Gael in April 1901. After the article appeared Synge was initially hesitant about returning to Inishmaan, for reasons Mrs Synge explained in a letter to her older son Samuel:

he heard … Martin McDonough [sic], his chief friend on the island … is offended with him because he put a version of a letter he got from McDonough in an article he sent to an American paper. John thought that he would be quite safe, but someone sent Martin the paper and he is offended. The letter was written in Irish to John and he put in a free translation I fancy.17

In the event, Synge did go back to the island and had no difficulty in persuading Martin to forgive him. What is striking here is Synge’s presupposition that an essay published in a journal in New York would not find its way back to Inishmaan. In fact, communications between Aran and the Irish diaspora would have been excellent, and something written about the islands in an Irish-American publication would hardly have escaped notice. Similar offence was taken, apparently, at Synge’s representation of his visit to the Blaskets. Máire Ní Catháin, the ‘little hostess’, was not pleased at being described as having made tea for the visitors on arrival ‘without asking if we were hungry’, nor yet at having taken off her apron to use as a curtain for Synge’s bedroom (a detail to be used in The Playboy). Muiris Mac Conghail, who reports this, assumes that the people would have read the essays in The Shanachie, but points out that ‘their relatives in Boston and New York were also a factor in the view of Synge; there was constant correspondence between the Islanders at home and in America’.18

Implicit throughout many of the travel essays, in some sense endemic in the form itself, is a contrast between the traveller observer, cosmopolitan, mobile, literate, and the culture he observes, oral, stable, more or less unaffected by modernity. Again and again, however, especially in the Congested Districts essays, Synge reveals the unreality of that contrast. The men and women of Mayo and Sligo travel regularly, every year, for seasonal work in England and Scotland. ‘The Homes of the Harvestmen’ reports on the hundreds going in the months of June and July on the boat from Belmullet to Sligo and from there on to Glasgow. Emigration to America is one of the central issues of the Manchester Guardian articles, viewed as the key social problem; the lace and knitting schools set up by the CDB to provide home industries only provide girls the money to emigrate. However, ‘returned Americans’ are also commented on a number of times, and there is a whole economy by which young women can work in the United States long enough to earn a dowry to marry advantageously back home. Differences of class, education and background, of course, remain between Synge and the people he meets and describes; but they live within a single modern world of trains and boats, the circulation of post and print.

Publications

It is widely and rightly accepted that the visit to Aran in May 1898 was to transform Synge’s career and make a writer of him. It is hard not to back project, therefore, and see the emergent playwright from that point on, regarding the travel essays largely as quarry for the great plays to come. But who knew in 1898 what sort of writer Synge was to be? After that first visit to Aran, Yeats reported proprietorially to William Sharp from Coole Park: ‘Synge a new man … I have started in folklore has been here on his way from the Arran islands where he has been seven weeks perfecting his gaelic and getting stories.’19 Nine months later, Yeats was still thinking of him primarily in these terms, commenting from Paris to Lady Gregory: ‘He works very hard & is learning Breton. He will be a very useful scholour.’20 Certainly a scholarly folklorist is what Synge looks to be in the first Aran essay, ‘A Story from Inishmaan’, which he published in November 1898 in the New Ireland Review.

The New Ireland Review was established in March 1894 by Father T.A. Finlay, the Jesuit priest and economist, as successor to The Lyceum, which he had also founded. Finlay was an active partner in Horace Plunkett’s Irish Agricultural Organisation, dedicated to promoting the principles of co-operation among Irish farmers. The New Ireland Review might be placed politically as moderately reformist, publishing articles and reviews on contemporary social and political questions as well as historical and cultural matters. So, for instance, in the November 1898 edition in which Synge’s essay appeared, there was a review-article by Finlay himself on the co-operative movement in Ireland and Britain, pieces promoting temperance, and a comparative study of Gladstone (very respectfully treated) and Bismarck, both of whom had recently died. In other issues of the time there was a running series of Irish religious songs, with texts in Irish and English, poems by Æ, an article on ‘West of Ireland Distress 1898’, and a polemic essay arguing for Irish language revival from D.P. Moran, later editor of The Leader. Synge’s ‘A Story from Inishmaan’ was collected from Pat Dirane on the island on his first visit in May 1898, a combination of narrative motifs used both in the Merchant of Venice (the pound of flesh) and Cymbeline (the wager on the wife’s fidelity). Synge’s comments on the tale-type and its analogues are almost ostentatiously scholarly, and his conclusion suggests that he regarded the article as a contribution to the study of comparative folklore.

There is little doubt that our heroic tales which show so often their kinship with Grecian myths, date from the pre-ethnic period of the Aryans, and it is easy to believe that some purely secular narratives share their antiquity. Further, a comparison of all the versions will show that we have here one of the rudest and therefore, it may be, most ancient settings of the material.

He claims that Dirane himself translated it for him from the original, ‘as my Celtic would not carry me through extended tales’ and adds, ‘I have kept closely to his language’. By the time this material is re-worked in The Aran Islands, however, the scholarly commentary is cut back, and the language of the story is substantially changed. The rather awkward standard English, with occasional constructions borrowed from Irish, has been revised into something very like Synge’s stage Hiberno-English.21

From his first visit to Aran Synge had hoped to write a book about his experiences there, and he worked away to that end over the years 1898 to 1902. It was to prove difficult to find a publisher for the manuscript, however, and he sought to place individual essays drawn from the material in periodicals. He found an outlet for ‘The Last Fortress of the Celt’, an account of Inishmaan, with The Gael where it appeared in April 1901. The paper obviously thought well of the essay because it was featured in large block letters at the head of the title-page. The Gael, with its alternative Irish title An Gaodhal, was billed as ‘a monthly bi-lingual magazine devoted to the promotion of the language, literature, music and art of Ireland’, and had been published in Brooklyn since 1882. Its nationalist political commitment had been even clearer in its original self-description as‘a monthly journal devoted to the preservation and cultivation of the Irish language and the autonomy of the Irish nation’. It did publish other Irish literary writers; the April 1903 issue in which Synge’s ‘An Autumn Night in the Hills’ appeared also included a story by Katharine Tynan (long-time friend of Yeats), and George Moore’s sharply ironic short story ‘HomeSickness’, as well as a letter from John Quinn defending the principles of the literary revival. ‘The Last Fortress of the Celt’, with a title drawing showing an Edenic naked youth on what looked more like a South Sea island than Inishmaan, stressed the primal character of Aran culture:

Title-page of The Gael

On an island in the Atlantic, within a day’s journey from Dublin, there is still a people who live in conditions older than the Middle Ages, and have preserved in an extraordinary degree the charm of primitive man.

Much of the material of this essay was to be re-used in The Aran Islands, but there were adjustments made for the periodical publication. So, for instance, the description of the keen was without the sceptical conclusion Synge gave it in the later text:

Before they covered the coffin an old man kneeled down by the grave and repeated a simple prayer for the dead.

There was an irony in these words of atonement and Catholic belief spoken by voices that were still hoarse with the cries of pagan desperation. (CW II 75)

Given the title of the essay and the likely sympathies of the readers of The Gael, the account of the eviction would have had a sharper political significance in the essay than in the book; even this last fortress of the Celt, it is implied, the dispossessing English have invaded.

‘The Last Fortress of the Celt’, The Gael, April 1901