Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

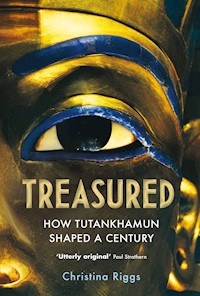

'Impeccably researched and beautifully written' David Wengrow 'Utterly original' Paul Strathern When it was found in 1922, the 3,300-year old tomb of Tutankhamun sent shockwaves around the world, turning the boy-king into a household name overnight and kickstarting an international media obsession that endures to this day. From pop culture and politics to tourism and heritage, and from the Jazz Age to the climate crisis, it's impossible to imagine the twentieth century without the discovery of Tutankhamun - yet so much of the story remains untold. Here, for the first time, Christina Riggs weaves compelling historical analysis with tales of lives touched by an encounter with Tutankhamun, including her own. Treasured offers a bold new history of the young pharaoh who has as much to tell us about our world as his own. 'Searching, masterful and eloquent' James Delbourgo

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 671

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TREASURED

CHRISTINA RIGGS is Professor of the History of Visual Culture at Durham University and an expert on the history of the Tutankhamun excavation. She is the author of several books, including Photographing Tutankhamun and Ancient Egyptian Magic: A Hands-on Guide.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2022.

Copyright © Christina Riggs, 2021

The moral right of Christina Riggs to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 053 8

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 052 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Introduction: Discoveries

1 Creation Myths

2 The Reawakening

3 Caring for the King

4 Rescue and Reward

5 The Dance of Diplomacy

6 Land of the Twee

7 Restless Dead

8 Tourists, Tombs, Tahrir

Conclusion: The Museum of Dreams

Acknowledgements

Timeline

Bibliography

Notes

Illustration Credits

Index

Preface to the Paperback Edition

THE GODDESS SELKET greets me, gilded and larger than life, in the arrivals hall of Cairo International Airport. Her arms reach out in welcome over a display of duty-free electrical goods, and her eyes follow the queue of laden luggage trolleys being steered through customs towards the sultry spring evening that awaits beyond. Ever since the ancient original of this oversized replica toured the United States in the late 1970s, the graceful, gowned figure with a scorpion on her head has been a fixed star in the Tutankhamun galaxy. She brings a touch of feminine allure, and sex appeal, to the pharaoh whose golden touch still shows no signs of tarnish, a century on from his tomb’s discovery.

I am back in Egypt two years later than planned, thanks to the pandemic. Tutankhamun’s treasures have been busy in the meantime, and Egypt has been gearing up for centennial commemorations in November 2022. The Ministry of Antiquities and Tourism has become adept at staging spectacular, multimedia ceremonies and parades with an eye on both home and foreign audiences. Broadcast live on social media, these showcase the country’s pharaonic past even as its present rulers bulldoze historic homes and medieval mausolea to make way for neverending, army-owned construction projects outside the densely populated capital. Wide highways lead to concrete satellite cities and a New Administrative Capital that sits in splendid, highsecurity isolation in the desert. If the government had a less selective view on ancient history, it might see in Tutankhamun’s own era a cautionary tale. To the young king fell the task of restoring cosmic order after his predecessor, Akhenaten, retreated to a new settlement at remote Amarna. Physical distance is no protection against some kind of reckoning, someday.

As a modern icon, Tutankhamun can often feel as hollow as his golden mask, which rumours say will have its own parade by this year’s end to shepherd it from the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square to the new Grand Egyptian Museum complex, twenty kilometres to the west. The upper galleries that have displayed the tomb objects since the 1920s are nearly empty now, although the core components of Tutankhamun’s burial remain: the carved alabaster chest that sheltered pieces of his internal organs; the solid gold coffin that held his shrouded body; and a handful of statues from his funeral rites, long stripped of their sacred linen wrappings. Conservator Eid Mertah and his colleagues have been hard at work on the largest of the astonishing wooden shrines that filled the burial chamber, layering tissue paper over its gilded surfaces and glazed blue inlays to protect them from whatever is to come. After nearly 90 years in the old museum, the shrine is due to be taken apart and put together yet again, echoing the efforts of the excavators as well as the carpenters some three millennia ago. History does not repeat itself, but humans do.

In Europe, North America, and Australasia, meanwhile, dozens of museums, publishers, and media outlets have plans in place to mark the centenary of the discovery this autumn, too. Tie-in exhibitions, conferences, TV shows, radio dramas, and books will recount the entwined tales of Tutankhamun, Howard Carter, and the tomb. Movie-goers not sated by another remake of Death on the Nile will soon hear the gravel tones of Iggy Pop narrating a big-screen documentary about ‘the last exhibition’ of Tutankhamun artefacts, which was brought to an abrupt end by Covid-19 and a legal challenge in Egypt. Denied substantial revenue from ticket sales and merchandise, its American organizers have turned to cinema instead. In the past century, Tutankhamun has wielded plenty of soft power, and inspired genuine awe, but he is also, always, synonymous with the kind of treasure that can be counted out in cash. The 5th Earl of Carnarvon knew that very well, and the 8th Earl has linked centenary events to his own venture, Highclere Castle Gin. At the annual conference of the American Research Center in Egypt, held in Los Angeles earlier this year, attendees could peruse a cocktail menu printed on a famous photograph by Harry Burton. It is February 1923 forever, and Carter and Lord Carnarvon have broken through the wall of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber to seize the prize they felt was theirs.

The conference is one of the largest academic events for Egyptology in the world, although it is difficult to imagine any other university subject flaunting its colonial origins so openly and without shame. The boundaries between its public outreach, research, and entertainment value have long been blurred. Already in Howard Carter’s day, Egyptology leveraged its popular appeal to fund its work and earn its place in the academy. The field might have died out had Tutankhamun not pumped new blood into its veins by inspiring successive generations of new scholars, often trained in old, unchallenged ways. I know, because I was one of them early in my career, and I am well aware that I play my own small part in the Tutankhamun industry these days. I do so in hopes of helping change both the story and who tells it. Unfortunately, the mainstream media, and its consumers, still seem to trust the authority and voices of white male writers and presenters above all. Asked repeatedly in recent months to contribute to ‘celebrations’ of the centenary, I have first asked which Egyptian scholars and commentators will be taking part (awkward silence often follows) and have then queried whether ‘celebration’ is the right word to use. Not only does it centre Egyptology’s triumphant narrative, but it also seems a callous way to characterize the despoliation of a sacred space that held not one, but three, burials. Three dead bodies that had outlasted grief.

The dominance of such self-satisfied accounts, and their casual perpetuation in so many arenas (schools, museums, the internet and media), is what spurred me to write this book. At the midpoint of my academic career, I found myself becoming an expert on the history of the Tutankhamun excavation, by virtue of my research on the photographs that made it famous. Yet in talking to public audiences, journalists, and western Egyptologists about what seemed obvious to me – namely, the imperial context of the discovery and the bias and oversights inherent in our historical sources – I often faced reactions of surprise, confusion, even doubt. Had the familiar story of this iconic archaeological find been misunderstood and misrepresented all these years? Wasn’t Howard Carter a real-life hero? And how could anything be more important than another headline-grabbing theory about Tutankhamun’s family line, his naked body, or his cause of death? Somewhere between blind faith in so-called science and sensational rehashes of the mummy’s curse, any sense of humanity and history in the Tutankhamun story had been lost. In writing Treasured, I hoped to bring them both back into view.

The Tutankhamun centenary comes at a time when there is growing acknowledgement that the impacts of European colonialism, global empires, and systemic racism have contributed to contemporary inequalities around the globe – and continue to sustain them. Tracing a longer history of the Tutankhamun excavation, as this book does, gives us an important insight into how antiquities, museums, and archaeology play their part in this. The British invasion of Egypt in 1882 created the conditions for Howard Carter to make his life and career there, while Egypt’s gradual reclaiming of its freedom began in 1922, the same year as the Tutankhamun discovery. There is not a single ‘Tutankhamun’ but many – and that is the real story, from the beloved boy-king of the hope-filled 1920s to the blank gold face that now stares out from a billion photographs and tourist trinkets. History helps us understand how and why our present world has taken its current form, for good or ill. It also gives us tools to imagine other, ideally better, possibilities so that we can shape a future built on those instead. That is why it matters who writes history and how: the more diverse the people who research and narrate the past, the richer, more accurate, and multifaceted our understanding of it can become.

From Cairo, I fly south to Luxor, where the Tutankhamun story started. In this long-established tourist town, there is no escaping either the famous pharaoh or the Englishman who brought him back to life. One hotel lobby boasts a convincing replica of the black-and-gilded head of Mehet-Weret, the cow goddess who guarded the tomb’s canopic chest. Another features several Burton photographs along its walls, most of them featuring Howard Carter in pride of place. The publisher of the Luxor Times, Mena Melad, gives me some context over dinner one evening: for the 75th anniversary of the tomb’s discovery in 1997, a lavish mini-series on Egyptian television portrayed Carter as sympathetic to the Egyptian people. Neither of us thinks there is much evidence for that, but the histories of colonialism and empire defy efforts to reduce their intimacies, and violence, to simple pairs of good and bad or black and white.

I am staying on the opposite riverbank, in the villages known collectively as Gurna that stretch westwards from the Nile and snake around the ancient sites. Howard Carter built a mudbrick home here in 1910, not far from where he was then excavating for Carnarvon and (conveniently, as it turned out) adjacent to the road heading west into the Valley of the Kings. On my visit, the house has been closed for several months, but a colleague arranges access and shows me around. Fine sand coats every surface like the dusting of flour on fresh pita bread. Two simple bedrooms and a study lead off a central, domed court. Down a short hallway is a dining room and drawing office; the kitchen with its lead-lined cold store; a bathroom; and a darkroom, too. An emplacement holds three pottery jars called zir, for the fresh water that was transported daily from the Nile. The house has been added onto over time, enclosing the sheltered area where Carter kept the cage for his pet canary, while the green lawn that struggles through the soil is not a luxury he knew. Refurbished as a tourist attraction in 2009, the house was dressed with secondhand furniture and vintage props to create a period feel, and, for a fee, tourists could sit at ‘Howard Carter’s desk’. Framed prints of classic Burton photographs still line the walls, as relentless as the temperatures outside. A fresh renovation, due to open in November 2022, will do away with these, restore original paint colours, and dress the house to reflect how Carter might have used the rooms. New interpretation panels, inside and out, will try to tell a more rounded, century-long story about how two men – Howard Carter and Tutankhamun – came to be so famous that we have forgotten to ask why they matter, and for whom.

On my last night in Gurna, a friend whose ancestor helped lead Carter and Carnarvon’s early excavations weaves us calmly and carefully among the other vehicles taking advantage of the less oppressive evening air. We have both lost loved ones in car accidents, and one upside of a road designed for tour buses is that it leaves ample space for the local traffic that picks up after dark, when most tourists have gone back to their cruise ships and Nile-side hotels. We pass tuk-tuks, sleek sedans, and several buzzing motorcycles, on one of which a small girl sits sideways behind her father, clutching a bouquet of henna flowers. I always think Egyptian traffic is a metaphor for how people here look out for one another, a choreographed, if somewhat chaotic, dance in a society where so many odds are poorly stacked and bigger road users threaten to block the way. Mahmoud is not at all convinced. In Egypt, he says, there is just one rule for driving – namely, that there are no rules.

At the Ramesseum Café, named for the nearby temple of Ramses the Great, we sip chilled bottles of Stella – the national beer – and gaze out towards the spotlights on the mountain. Thanks to Mahmoud, I’ve learned that we are a stone’s throw from where the family of Ahmed Gerigar (or Gorgar), the lead Egyptian archaeologist at Tutankhamun’s tomb, had a home before the clearance of Old Gurna knocked it down several years ago. Antiquities have precedence over people here, a landscape turned into a museum by enclosure walls, police checkpoints, and all those spotlights, which throughout my stay inspire conversations about electric bills, the Ukraine war, and the COP27 meeting due to take place in Cairo soon. No one can recall such a scorching May.

People come and go around us, peeking at the puppies in the kennel or admiring the new entrance several young men are making in the courtyard wall, to a steady rhythm of mallet thuds. It could be any summery smalltown evening, with nowhere in particular to go and nothing much to do. Inside, one wall of the café is lined with framed photographs and newspaper articles about the Abd el-Rassul family, who have had the government concession to run it for several decades now. Sheikh Hussein Abd el-Rassul found fame late in life when he identified himself as the boy wearing one of Tutankhamun’s necklaces in a photograph taken by Harry Burton in 1926. Some say a German journalist brought Sheikh Hussein the photo during the Tutankhamun revival of the 1960s or 70s, others that he had a copy given him by Burton himself. It is the Burton photographs that keep the past so present, for they made the story of Tutankhamun what it was and what it has become. The real archive went home with Howard Carter, but in this communal space, its shadow version is the surest way for local people to claim their place, any place, in the tale. For many, it is their families whose knowledge, land, and labour made archaeology possible, but the weight of history is unevenly distributed, as are its benefits.

We finish our beers and rise to go. I too am headed home to England in the morning. I take the sprig of henna Mahmoud has plucked for me, its scent sweet-sharp and heavy in the heat. Behind the mountain, in that deep valley, perhaps protective goddesses still welcome Tutankhamun with fresh flowers and cool water in the twelve dark hours of the night. For his sake, I hope so. And for ours.

CHRISTINA RIGGS, June 2022

INTRODUCTION

Discoveries

THE PROJECTOR DRONED a dead buzz as we waited, desks abandoned. We were gathered in our plastic chairs at one side of the classroom, turned towards the pull-down screen where a white square promised a window to another world. If only Mrs Williams would thread the filmstrip and begin.

At last the square changed colour, and a set of shaky words appeared. Life in Ancient Egypt, or Land of the Pharaohs, perhaps. Beginnings always scroll by unremarked. With a thwack of its lid, Mrs Williams shut the cassette player and signalled us to silence. The tape squeaked into life and settled into the sonorous tones we knew from other filmstrips we had watched at Sander-son Elementary School in rural Ohio. In 1983, the authoritative voice of knowledge was deep, male, and often out of sync with the images before our eyes. Teachers – even young and pretty ones, like Mrs Williams – tended to miss the tone that told them to advance the projector to the film’s next frame. The voiceover moved on to George Washington’s harsh winter at Valley Forge, or the effects of chlorophyll, while we were still watching Paul Revere’s midnight ride or staring at the yellow sun.

Today was life and death: we were about to embark on ancient Egypt. On wan winter afternoons, we had already been to Mesopotamia, ‘Cradle of Civilization’, between the Tigris and Euphrates. I had stared at two blue rivers in the textbook map, afraid someone would see that the dots along them – Nineveh, Babylon, Ur of the Chaldees – were already familiar ground. My cheeks burned as my separate worlds, of school and church, were forced to meet. In class, Mesopotamia was the land of ziggurats and Hammurabi. In church, where my family spent long Sunday mornings, Mesopotamia was the land of Abraham, whose God was ours.

If Mesopotamia seemed too close, would ancient Egypt be too far? The filmstrip took us swiftly to the Nile, a blue line snaking north and opening like a flower. Life-giving waters, the voiceover intoned. Mighty pharaohs, and the pyramids appeared. Cranes hauled a temple piece by giant piece into the air. A beep, and we were in the Valley of the Kings, waiting for Mrs Williams to catch up. Death was on the way.

Another beep, another frame. A boy who had been king but died too young. His name, the voice as deep as God’s announced, was Toot-ankh-a-MOON. His tomb was a time capsule found intact, his life preserved at the moment it had ended. Everything had been left just as it was more than 3,000 years ago. There was even an old photograph to prove it, as photos seem to do. The beep again, and something wonderful shimmered into view. A miniature coffin, a can-oh-pick, according to the soundtrack syllables. But I was not listening. I was looking. Its surface alive with jewel-like colours, the can-oh-pick container filled the filmstrip square in defiance of its small size. Above the intense blues and blood-rich reds of its feather-patterned body, a little gold face, set seriously towards the future, wavered on the screen. My skin tingled. I willed Mrs Williams to forget to advance the film this time.

When the recording beeped, however, Mrs Williams pressed the button. The projector hummed; the filmstrip shuddered forward. No matter: the golden face was fixed now in my mind. Toot-ankh-a-MOON. Ten years old and miserable, I had never seen anything so splendid and surreal. I had to know more about this Tutankhamun and his tomb in the Valley of Kings, not knowing, not able even to imagine, how it would change my life.

* * *

Tutankhamun at ten years old had a better idea of where his life was heading. Born a prince, perhaps he grew up knowing that he might be king of Egypt one day, even if becoming king at nine or ten years old was premature. One thing he could not have known was that he did not have long to live – nor could he have imagined that death, and a quickly finished burial, would take him from his world into ours.

It’s difficult now to imagine the past century without Tutankhamun and the discovery of that time-capsule tomb. Had Howard Carter’s crew of Egyptian archaeologists been less thorough and overlooked the rock-cut stairwell to the jam-packed set of four small rooms back in November 1922, history would have overlooked Tutankhamun. Instead, this long-lost king, buried before he was out of his teens, found more fame and influence in the twentieth century than he had ever known in his own lifetime. Without this little-known ruler, Howard Carter, a self-taught and temperamental British archaeologist, might have died a failure, not a heroic household name. His sponsor, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, might have died of old age instead of an infected mosquito bite in his Cairo hotel room. There would have been no media frenzy of Tut-mania and mummy curses to kick-start the jazz age, and no surge of corresponding pride in the newly independent nation-state of Egypt, where Tutankhamun was a ready-made symbol of the country’s longed-for resurrection.

From the moment the beds and boxes and burial trappings in his tomb reversed their journey up those stairs, Tutankhamun began to shape the politics of the Middle East – and the global popularity of ancient Egypt, like no other archaeological find before or since. The modern world would never be the same, not only for the events that surrounded the 1920s discovery of the tomb, but also because that proved to be only the pharaoh’s first rebirth. A Tutankhamun revival in the early 1960s helped the United Nations’ cultural arm, UNESCO, keep the temples of Nubia from disappearing beneath the backed-up waters of the Aswan High Dam, as the ancient source of the pharaoh’s gold (the noub of Nubia) was sacrificed to hydroelectric power. In his second career as a cultural ambassador, Tutankhamun – or at least, a selection of objects from his tomb – toured the United States and Canada to draw attention to the Nubian temples’ plight, then travelled to Japan to raise the funds that saw the rock-hewn sanctuaries of Abu Simbel winched to higher ground. The miniature coffin that had dazzled me on screen once gazed up in golden calm at Jacqueline Kennedy, who opened the first ‘Tutankhamun Treasures’ exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in November 1961. It was the gilded start of the Kennedy presidency, when hopes for a fairer society and American leadership were high and culture was the kindest weapon the Cold War had at its disposal.

By the 1970s, when I was born, hopes had lowered and culture had been sharpened to a point. As the Middle East peace process and free-market economics entangled Egypt with America, Tutankhamun did the diplomatic work of presenting his homeland as a friendly face and worthy ally. ‘Every American should know more about Egypt and the Middle East,’ declared a catalogue of educational media published by the United States Office of Education in 1977.1 Filmstrips like those we watched in my small-town school were part of a concerted effort to educate Americans about the region and cultivate a positive attitude towards Egypt and the Arab world, the source of the oil on which the American way of life depended. A new tour of Tutankhamun’s treasures in the late 1970s had a similar effect. Mrs Williams had been to see it, returning to Ohio inspired and well supplied with books, posters, and a teacher’s guide from the museum shop. Only later would I realize how much this coincidence had shaped my ten-year-old self, and only later still would I see that it wasn’t much of a coincidence after all. Ancient Egypt was not on school curricula by chance, nor had Tutankhamun permeated American culture by force of personality. On the contrary, he was a blank, a wide-eyed icon – and all the more powerful for it, as a symbol of luxury, might, and ultimate command. All that gold, which defied time, made it seem as if the lost young man in the middle of it all had defied death itself.

He hadn’t, of course, but in the hundred years that have passed since the discovery of his tomb, Tutankhamun has found an afterlife far different than anything intended by the ancient priests who oversaw his burial. In 2022, museums and the media around the world are marking the centenary of the discovery with a focus on the triumphant tale of 1922 and the treasured status of the tomb and its objects today. This book tells the story of what happened in between and why it matters. The history of Tutankhamun in the twentieth and now twenty-first century shines a light on several things we take for granted (celebrity archaeologists, UNESCO’s World Heritage scheme, blockbuster exhibitions) and several more we need to challenge (systemic racism, global inequalities, climate change). All of these are linked. The archaeological heroes of movie plots and TV documentaries descend from excavators whose work was an integral part of Western colonialism and empire-building in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – systems that relied on racism through and through. As colonized countries demanded independence in the wake of two world wars, UNESCO emerged as an international body that promoted peace through culture, yet its early efforts at protecting heritage sites turned a blind eye to the forced migration of 100,000 Nubians in Egypt and Sudan – and the idea that places matter more than people has been difficult to shift. The museum blockbusters that grew up around Tutankhamun’s treasures went hand in hand with capitalist excess, Cold War politics, and the dizzying, detrimental heights reached by weapons sales and fossil fuel extraction in the Middle East. Tutankhamun did not create the climate crisis, or invade Iraq, but his story helps us see how deep and intertwined are the roots of cultural, political, and social phenomena we usually treat as separate plants. They have grown in the same soil, and to understand and change them, we must start from there.

By covering a century of Tutankhamun’s history, between 1922 and now, this book departs from conventional accounts of the great discovery and the golden treasures to offer quite a different take on this ancient Egyptian ruler, whose short life yielded such a surprising afterlife. Amid growing awareness of the need to challenge historical biases and their implication in contemporary prejudices, it is time to take a more rounded look at how the tomb was located, cleared, and studied; what happened to the objects and the excavation records; and why ‘King Tut’ has been headline news for several generations. In researching and writing my account of Tutankhamun, I have tried to give priority to stories, and storytellers, that have been ignored, overlooked, or even erased from Egyptology. Here you will find the Egyptian archaeologists, poets, politicians, curators, and many others who have been looking after Tutankhamun’s legacy for a hundred years. You will learn (if you didn’t know already) that Tutankhamun and his family are a long-standing part of Black heritage for African-American and other African diaspora communities. And you will read about the often unknown and little-recognized women without whom Tutankhamun would not have stepped back into the limelight in the latter half of the twentieth century.

It is a human story and, I hope, a humane one. It draws on personal history as well, for Tutankhamun shaped my life in ways Mrs Williams could not foresee: I became an expert on ancient Egypt and have spent thirty years studying and working at universities, delving into archives and museum storerooms, even turning up as a talking head on television documentaries now and then. But with its determined focus on the ancient world, at the expense and exclusion of the modern, Egyptology did not live up to my childhood dreams. Mid-career, I took a sideways step to rethink, retrain, and refocus my attention on how different people, at different times and places, have imagined ancient Egypt, and why. In this book, I weave together memoir, travel, art, and archaeology in order to write a history that is revisionist in the best and truest sense of that word: to revise an accepted or established version of events. Its Latin root, re + videre, means to look again, and it is by looking over new evidence, or from a new angle, that we can see the past, the present, and ourselves with fresh eyes.

Tutankhamun’s own unblinking eyes gazed out from a poster Mrs Williams hung behind her desk and from the cover of the exhibition catalogue she brought for us to leaf through, carefully, in class. Saturated colour photos gleamed between the covers: the gold-and-blue-striped mask, the alabaster vases that seemed to glow with their own light, and the graceful, gilded figure of a goddess with a fat scorpion perched incongruously atop her head. The words that poured across the pages enchanted me as well, and even the strange silvery tones of old photographs that showed the objects still in the tomb, stacked every which way like the boxed-up Christmas ornaments, camera equipment, and jigsaw puzzles that jostled in the cupboard underneath the stairs at home.

I beamed inside with pride when Mrs Williams let me borrow the catalogue for one precious weekend. I slid it gently into my school bag with what was left of my paper-sack lunch and long-division homework. In my house we respected books but rarely bought them, much less left them lying around to browse at will. My mother’s historical romances fought for space with folded sheets in the linen closet, and volume by volume she was acquiring a Funk & Wagnalls encyclopaedia for the family, with saving stamps from the Big Bear grocery store. Above his desk in the damp half-basement room we called the den, my father kept a trusted Strunk & White and a paperback of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the year that was so ominously on its way. A dark, forgotten bookcase held my parents’ musty college yearbooks, which I leafed through on wet afternoons, seeking out my mother in her cats-eye glasses, and my father, shoulders padded out beneath his football jersey. Sometimes the past seemed very long ago.

Upstairs, inside a cabinet in the living room, were two books that needed my mother’s permission to peruse: a family medical encyclopaedia and a similarly weighty Reader’s Digest tome, an illustrated history of the world with the ambitious title The Last Two Million Years.2 Cross-legged on the floor, my back against our green tartan sofa, I pulled the book onto my lap and opened its marbled covers on my knees. The spine’s stiff glue gave a satisfying crackle, the pages crisp with underuse. I flipped past a naked, hairy caveman skinning a deer (‘man masters fire’) and stopped briefly at a drawing of the four races of man (all shown, indeed, as men). Mesopotamia I had already exhausted (‘among the Sumerians, civilized society takes shape’). What I wanted now was Egypt.

And there it was. The river Nile, the gods and kings, the stone solidity of temples, pyramids, and statues. This was a better Egypt than the Bible offered, with its sinister magicians, evil pharaoh, and drowned army. After supper, I smoothed a sheet of poster-sized paper across the kitchen table. In neat rows, I drew a dozen Egyptian deities for Mrs Williams’ class, labelling each with unfamiliar names (Osiris, Thoth, Isis) and divine responsibilities (death, writing, motherhood and magic). My own mother hovered anxiously. God had forbidden graven images, but I sat quietly colouring them in as she dried saucepans. ‘You aren’t getting . . . involved in those things?’ she asked, as if I might be starting to believe in winged women and bird-headed men. I didn’t believe in her God, which I think she sensed. She worried about my teenaged brothers too, convinced that satanic messages had been embedded, backwards, in their Led Zeppelin albums. ‘It’s for extra credit,’ I offered by way of an answer. I didn’t believe in Isis or dark jackal-headed Anubis, no, but I found it reassuring to know that other people had. It was proof that there were other ways of living, thinking, being, even dying.

To reject God was to face damnation. But that was exactly what a pharaoh named Akhenaten had done, according to The Last Two Million Years. Breaking with the old religion that honoured a god named Amun, this king and his queen, Nefertiti, had created a new way of worshipping the sun disc, known as Aten. Unlike the gods in hybrid human forms, shown with animals on their heads or in place of them, Aten was a perfect circle with rays of light beaming down to bless the royal couple and their daughters. In some respects, Aten worship paralleled and prefigured the monotheism of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. There was only one sun, after all. A hymn to Aten, said (on slim evidence) to have been written by Akhenaten himself, reminded me of the sing-song rhymes and soaring refrains that were the best part of Sunday services. ‘You rise beautiful from the eastern horizon,’ it praised Aten at dawn. Yet sunset always followed. ‘You rest in the western horizon,’ it mourned, ‘and the land is in darkness like death.’

Flipping the page on Akhenaten, I came face to face with Tutankhamun. The boy king was credited with returning Egypt to its old gods, for the better. He changed his name to mark the restoration, from Tutankh-aten, ‘living image of Aten’, to Tutankh-amun, the living image of the god Amun, a creator whose own name meant ‘the hidden one’. I pored over photographs that showed more of the exquisite objects from the tomb. They were in colour, like my favourite photographs in Mrs Williams’ catalogue, except for one small shot in grainy shades of black and white. Boring by comparison, like Kansas before the vibrant Land of Oz in the Judy Garland film that I watched eagerly on TV each year. I was sceptical of too much monotone intrusion of twentieth-century life between myself and ancient Egypt. Why couldn’t I get straight there, in full colour, to the facts?

I looked at the dull picture again. A man, two men, or more, peering into some kind of doorway. Light streamed past like Aten’s rays, leaving them in shadows. I read the text nearby, which informed me that Lord Carnarvon and Howard Carter had opened the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922. Were these the men in the photograph, I wondered, and what was a Lord if not the Lord? I pushed my heavy eyeglasses back up my nose. The text was short, the typeface tiny. It told a story we seemed already meant to know: at the bottom of a flight of steps, before a bricked-up opening covered with ancient seals, Carter chisels out a hole just wide enough for a torch beam and his peering eyes to pierce. ‘Can you see anything?’ this Lord Carnarvon asks, and Howard Carter has to reply. ‘Yes,’ he says. ‘Wonderful things.’

* * *

Except he didn’t say it, nor was that a photo of the fateful moment when Carter and Carnarvon first breached the sealed doorway of the tomb in November 1922. A century on, these details have been lost in all the tellings and retellings of the tomb’s discovery. I found that out much later. First I had to make my own discovery about happenstance and history. What survives, and what is lost. Who tells the tale, and who slips through unnoticed, unnamed, disregarded, overlooked.

I fuelled my passion for the past by scouring books, acquiring facts, and immersing myself in a vividly imagined ‘Ancient Egypt’. I wanted a story that was whole, unfractured, and for that I needed more than those few pages in The Last Two Million Years or Mrs Williams’ catalogue could give me. Fortunately, every other Saturday was for the public library. My mother had been taking me since I was small, when the library was upstairs in the town hall, a fortress of Indiana sandstone whose blocks had travelled to Ohio by a system of canals that had long ago run dry. By the time I was ten, the library had moved to a new red-brick building, its gambrel roof blending into the grid of downtown streets, between the steepled churches, stolid banks, and columned porches of historic houses. An entire floor housed children’s books, where I could spot familiar favourites on the unfamiliar shelves.

Egypt was elsewhere, I soon discovered. A kind librarian showed me how to find it. I slid a drawer out of the card catalogue, as she had done. Its brass pull, curved over my fingers, felt snug and protective. The cards inside brushed by my fingertips as I flipped through subject headings. Each card a book, and there were dozens, hundreds, of them. EGYPT, ANCIENT, was on the ground floor, in ranks of non-fiction organized by Dewey decimals, a system we had learned about in school. Non-fiction: the world of the real, but no less an escape for that.

I checked out as many books as I could carry. My schoolmates already took me for a four-eyed geek, a freak who had skipped a grade and could not name the members of Duran Duran. Books were a retreat. I liked the squared-off stillness of Egyptian statues, the symmetry of carved friezes, and the colourful wall paintings, each figure precisely distanced from the next. In the ancient Egypt I had started building in my head, everything lined up in ordered rows of images and neat blocks of printed text. Lists of kings formed tidy timelines, too, although the reigns each side of Tutankhamun trailed off in question marks. I wondered why. His name was near the end of the 18th Dynasty, which had lasted for 250 years (around 1550 to 1300 bc) and seemed to be Egypt’s golden age, in every sense, as the kings amassed wealth through military conquest and savvy trade deals. My books referred to the last few decades of the dynasty – Tutankhamun’s era – as the Amarna period. Amarna, I read, was where a king who came before him, Akhenaten, had established a new city in a sheltered bay of cliffs. It was set back from the Nile as if its residents could thrive on sun alone, without water to quench their thirst or let them sail away.

Unlike Egyptian rulers who had been known for centuries in Western Europe, thanks to Greek and Roman writers and the Bible, the famous names of the Amarna age – Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamun – were fresh discoveries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Their stories have been filtered not through the literary imaginings of the Renaissance (Shakespeare’s Cleopatra) or Romantic era (Shelley’s Ozymandias, who was Ramses II, ‘the Great’), but through the mass media and popular culture of European empire. In other words, modern history determines what we know about this period, and excavating the layers of our own past is the only way to tell what can, and can’t, be said with any certainty about the life of Tutankhamun and his relationship to other Amarna rulers.

Amarna itself was excavated in the 1880s, around the time that Britain invaded and occupied Egypt. The remote site excited scholars and the public alike because it yielded an archive of diplomatic correspondence, impressed in clay tablets using the wedge-shaped cuneiform script that was common in ancient Syria and Iraq. Written in Akkadian, the letters name places and rulers that correspond to some Old Testament accounts, which captured the imagination of devout Victorians eager to map the Bible on to the Middle East. Amarna also stood out because it was an urban settlement, rather than the usual tombs and temples found in Egypt. Tutankhamun probably spent part of his childhood in the city’s palaces, but Egyptian kings and their entourages were often on the move, making appearances, holding court, and taking luxurious trips to hunt prey out in the desert or fat wildfowl among the Nile marshes.

In the early 1890s, influential British archaeologist Flinders Petrie excavated at Amarna – with young Howard Carter to help him. Petrie used lectures, exhibitions, and the illustrated press to publicize his finds and raise money for future work. He made Akhenaten and the royal family fit the domestic ideals of late Victorian Britain, the king a proud pater familias who tended the garden in his spare time and dandled his six daughters on his knees as their mother, Nefertiti, looked on and smiled indulgently. But there were soon several Akhenatens circulating. When American academic James Henry Breasted – an observant Christian who had first trained to be a Congregationalist minister – published a bestselling history of ancient Egypt in 1906, his Akhenaten was a Protestant reformer, a monotheist ahead of his time whose life and rule collapsed in opposition from the idol-worshipping, papist priests of Amun. In this version of events, Amarna was a utopian interlude that could not last, and Tutankhamun was a child manipulated into restoring the old gods.3

A more avant-garde and edgy Akhenaten emerged on the eve of the First World War, when German excavations at Amarna uncovered several limestone and plaster portrait heads in what appeared to be a workshop for making sculpture. With their unfinished edges and exquisite forms, they might have come right out of a contemporary sculptor’s studio, works in progress for the modern age. The most remarkable was a painted bust identified as Nefertiti, discovered in 1912 in excavations led by the German Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt and funded by Berlin-based cotton magnate James Simon. For several decades, the French-run antiquities service in Egypt allowed excavation sponsors to keep a portion of what they found, based on an agreement reached at the end of each winter digging season. That year, the French official who visited Amarna to agree the division made a cursory inspection and ceded the stunning sculpture to the German team, rather than claiming it for the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.4 James Simon kept the bust with the rest of his art collection at home in Berlin until 1920, when he donated it to the city’s Neues (New) Museum, together with other Amarna finds. The museum waited to put the bust on public display until 1923, after Howard Carter found the tomb of Tutankhamun. Queen Nefertiti became an instant icon, a pale-skinned beauty equally as enigmatic as her husband Akhenaten and the boy king who came after them. Before his death in 1932, Simon wrote to the Prussian minister for culture (the regional authority for Berlin), supporting calls for the bust to be returned to Egypt. Times were changing, as were German politics: when Hitler’s National Socialists came to power the next year, a large plaque at the museum in honour of Simon – like Borchardt, a Jew – was taken down and all references to his donations expunged.5

Nefertiti, Akhenaten, Tutankhamun. Firm facts about these ancient individuals are as dry as an Ohio canal, compared to the soap opera psychodramas that have been woven around them. Tutankhamun was part of Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s family, but specialists still disagree on the specifics, including who his parents were.6 Analyses of ancient DNA have lately claimed to offer firm solutions, but they are a house of cards built on a shaky table. For a long time, scholars like Petrie and Breasted assumed that Akhenaten and Nefertiti had only daughters, because the six princesses appeared so often with their parents and never with any princes present. The logic hasn’t held up, however. In this period, the 18th Dynasty, the conventions of Egyptian art meant that a reigning king was not shown together with his male children. Tutankhamun may therefore have been Akhenaten’s son, either by Nefertiti or by a different wife.

Ra’is Mohammed es-Senussi holds the bust of Queen Nefertiti, which he and his team excavated at Amarna, 6 December 1912

Other theories have proposed that Tutankhamun was Akhenaten’s younger brother or half-brother, or most recently that he was Akhenaten’s grandson, born to one of Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s older daughters.7 It’s a puzzle with a hundred pieces, many of them missing; hence the question marks around the line of succession between Akhenaten and Tutankhamun, too. After Akhenaten’s death, a woman described as ‘beneficial for her husband’ and ‘beloved of Akhenaten’ took over for a year or two. She may have been his daughter Meritaten or his widow Nefertiti, taking on new names as every pharaoh did. Either before or after this ‘beloved’ came a ruler named Smenkhare, whose identity is even less clear. Perhaps he was Tutankhamun’s older brother or, in a recent reconstruction of the family tree, his father. One Tutankhamun specialist believes that Smenkhare was a new name for Nefertiti as her independent rule developed. Whatever the case, Smenkhare reigned a short time too, leaving only the boy still known as Tutankhaten to take on the rule of Egypt.

Two pieces can be anchored into place in the jigsaw of Tutankhamun’s origins and family life. First, he married the third daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, a princess named Ankhesenpa-aten who, like him, changed the last portion of her name in honour of Amun, becoming Ankhesen-amun. Whether she was his sister, half-sister, or aunt, and what the difference in their ages was, remains unknown and probably unknowable. The figure and name of Ankhesenamun appear on many of the best-known objects from Tutankhamun’s tomb. On the backrest of the gilded chair known as his throne, she is clad in silver and lays a hand on her husband’s body, anointing him with scented oil.8 In the gold leaf covering a small wooden shrine, he pours water into her cupped hand to drink.9 Male and female went together in Egyptian thought, and every king needed his counterpart in a queen who could balance, define, and refuel his masculinity.

The second puzzle piece to fix in place is this: Tutankhamun was born a prince and recognized as such in childhood. On a carved limestone block later used as building rubble, his slender, dangling legs appear alongside the royal formula that identifies him as ‘the king’s son of his body, whom he loves’.10 History has little use for love, however, and it makes scant room for women, children, and the dispossessed.

Whoever Tutankhamun’s mother was, the absence of her name or image anywhere in his tomb, or on any monument from his reign, probably indicates that she had died before he became king. Rulers of the time with living mothers made those women prominent, alongside or in place of their own wives. We do know about one woman who cared for Tutankhamun in his younger years. Her name was Maia, and her privileged role as the prince’s wet-nurse gave her the social status and financial means to build a large and lavishly decorated tomb in the cemetery of Saqqara, west of Cairo.11 She had earned the right to represent the king inside her tomb as well, and on one wall, Tutankhamun sits on Maia’s lap, depicted – according to convention – as if he were a miniature adult in her embrace. Prince and king, child and man, at once.

By the time this orphaned boy came to the throne around 1332 bc, Akhenaten’s palaces at Amarna had been abandoned in favour of older royal residences, such as those at Memphis, near Cairo, and Thebes – the name Egyptologists use for the ancient site that lies beneath and among the streets of modern Luxor, as if a different name were all it took to separate the past and present into discrete parts. In Tutankhamun’s childhood, a turn back to the old gods was already under way, and no surprise. The specific form of Aten worship that Akhenaten had promoted, with himself and Nefertiti in star roles, was not sustainable once both were dead. Tutankh-aten quietly became Tutankh-amun, and both those names appear on a handful of objects in his tomb. More important for Egyptians was the new name he adopted on becoming king: Neb-kheperu-re, which identifies him with the visible forms (kheperu) of the sun god, Re.

Becoming king may have meant leaving childhood behind, but some traces of that childhood, and of the family who predeceased him, were set aside for safekeeping. When Tutankhamun died, aged around eighteen or nineteen, these keepsakes joined him in the tomb. A single linen glove, sized for a child’s hand, was folded up in a delicately painted box, one of the ‘wonderful things’ that Carter spotted in his initial glimpse of the tomb’s first room (the Antechamber, as he called it).12 Nearby, a child-sized ebony chair was tucked neatly under a gilded bed carved like a lioness, probably used to support the wrapped-up, embalmed body of the king in funeral rites.13 Draped over the body of the jackal figure that kept watch over Tutankhamun’s burial shrines was a linen tunic, freshly pressed and marked in ink with what looks like the name of Akhenaten and ‘year 9’, perhaps the date in that king’s reign when the garment had been made.14 A slender ivory writing case, with wells for six different shades of paint or ink, lay between the jackal’s forelegs, lined up with precision.15 The hieroglyphs incised upon its surface name Princess Meritaten, Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s eldest daughter. Depending on how you fill the gaps in your Amarna puzzle, Meritaten may have been the wife of Smenkhare, the woman who briefly ruled before or after him, and the mother of the young man whose body had been secreted away inside those burial shrines.

Meritaten, or another woman who ruled as king, is a silent presence elsewhere in the tomb as well. The miniature coffin that had sent goosebumps up my arms had not been made for Tutankhamun but for a royal woman.16 Tutankhamun’s names are on the lid, spelled out with inset slivers of coloured glass and carnelian. But on the inside of one lid, chased in the beaten gold, are faint outlines of the hieroglyphs that wrote out ‘beneficial for her husband’, a phrase that imbued the queen with the qualities of a goddess. Gold workers had begun to craft a set of these containers for this woman’s burial, to hold the corpse’s embalmed viscera. For some reason (speed? convenience? family ties?), the craftsmen repurposed the four coffins, each around 40 cm high, for her successor – and perhaps son – instead. Shimmering in blue, turquoise, and red, the feathered body distracts the eye from the reworked name. Whoever the queen of these so-called canopic coffins was, she is no more than a shadow beneath the outer shell, or what historians call a palimpsest – a surface that has been erased and written over, rubbed almost smooth to start again. It makes a useful metaphor for history itself, with a gentle warning and an urgent plea. To see the past and its endurance in our present, we have to turn time’s mute survivors towards the light.

* * *

Emptied cities, orphaned children, faded names. History finds gaps through which to slip. Buildings, artefacts, and bodies are always tending towards decay, no matter how we try to stave it off. Not everything from the past can survive in physical form. But something more than physical survival determines how history manifests itself in school curricula, museum displays, and television shows. The old truism is still too true: history is often written by the winners, or at least by those with enough power to shine its spotlight where they choose. The history of Tutankhamun’s tomb and its discovery is no exception.

When he stepped into the first chamber of the tomb, Howard Carter felt that he was stepping back into the ancient past. Three thousand years had vanished like a time-travel tale come true, and like a time traveller, Carter described his initial shock and sheer bewilderment in the journal he began to keep, its self-conscious prose a practice run for future publications. ‘Yes, it is wonderful,’ he recollected in its pages, as his reply to Lord Carnarvon’s anxious query.17 What, if anything, was visible beyond the stifled corridor they had followed underground? Only one person at a time could see through the hole Carter had made in the blocked-up opening at the corridor’s end, and only by the light of an electric torch that shone into utter darkness. ‘The first impression’ of the space they saw, wrote Carter, ‘suggested the property-room of an opera-house.’ He crossed out the last two words and moved a different phrase there from two lines above: the property-room of ‘a vanished civilization’, the sentence became, as if the past had staged itself for Howard Carter to find.

In some respects, the tomb of Tutankhamun was, indeed, a staging place, prop room, and storage cupboard all at once. Burying a king was busy work. So was finding him. Howard Carter had been working for the Earl of Carnarvon for fifteen years by the time they stood at Tutankhamun’s threshold. After the fact, Carter characterized the tomb’s discovery as the culmination of a personal quest, and histories of archaeology have continued to oblige, embroidering an adventure tale with Carter as a lone hero battling against the odds and Carnarvon’s dwindling funds. But writing history means looking forward in time, not back. Since resuming work in 1917, Carter and his Egyptian team, led by Ahmed Gerigar, had progressed from one end of the two-pronged Valley of the Kings towards its centre, clearing built-up debris down to bedrock. A tourist site already in Roman times, more recent visitors had searched the valley high and low for decades, yielding the entrances to sixty-one tombs. Some were cut into the rock faces of the valley, its geology carved millennia ago by a long-vanished river; others were cut into its floor – like Tutankhamun’s, which became tomb sixty-two. The later, larger tomb of Ramses VI, with a vertical opening, dwarfed the area where Tutankhamun’s burial lay. Over time, layers of rockfall, earth, and everyday detritus covered the spot further, until a pick, shovel, trowel, or broom wielded by one of the Egyptian excavators revealed the contours of a stony step. Sixteen steps led underground, in a stairwell that measured barely an arm span and forced grown men to crouch until they were halfway down it. At the foot of the stairs was a blocked-up doorway, then a rubble-filled corridor sloping steadily underground for more than 7 metres, and finally the second blocked doorway that stood, in Carter’s mind, between present and past. Between him and the wonderful things.

One of Harry Burton’s first photographs inside Tutankhamun’s tomb, showing the plaster-covered entrance to the Burial Chamber, taken in December 1922

The first room that Carter glimpsed by torchlight proved to be one of four and the largest at 8 metres long and 3.6 metres wide, with a comfortable clearance overhead. Carter may have imagined himself in the property-room of a vanquished civilization, at that first impression, but he had not yet imagined the full extent of the tomb and its contents, nor the rationale for its creation in antiquity. The other three rooms leading off from the first were probably hacked out of the bedrock after the pharaoh’s unexpected death at a young age, around 1323 bc. With no tomb ready for him in the Valley of the Kings, where other rulers of the 18th Dynasty had been buried, the officials in charge of Tutankhamun’s burial seem to have adapted a tomb created for a lesser royal, which consisted of a single chamber at the end of a staircase and corridor.18 Carter came to call that room the Antechamber. In its back wall, an opening about 1 metre high gave access to a second, much smaller room that was quarried out to serve as one of the ritual storerooms required for royal burial equipment. Carter understood the ritual purpose of this space, which he called the Annex and saved for clearing last, more than five years later. Archaeology is slow work.

What grabbed the excavators’ attention first was the plastered-over wall at the short, right end of the Antechamber. This proved to be the blocked opening into a third room whose generous dimensions (6.4 metres long, 4 metres wide, with a 3.6 metre ceiling) were obscured by its stunning contents, for this was the Burial Chamber where Tutankhamun’s embalmed body lay deep within a thick cocoon of gilded wooden shrines, a linen-covered tent (or pall), a quartzite and granite sarcophagus, and three coffins, each also shrouded in cloth. The head of this ensemble lay at the west end of the space, so that the dead would catch the first rays of the rising sun on his face. The foot end of the burial led into the fourth and final room, at a turn to the right. Carter first called this ‘the storeroom’, but then changed his mind to Treasury. It is another ritual space essential to the efficacy of Tutankhamun’s burial – but the line between storage and sanctity is faint. There are no rites without the paraphernalia that goes with them. Folding something away, boxing it up, labelling the crate, and sweeping clean the floor: those are care-taking activities, too, even if the priest who spoke the prayers and wafted around the incense has long gone home for lunch.

No one knows how Tutankhamun died, only that he was eighteen or nineteen years old – a grown man by the standards of his day. Unexpected as his death probably was, a well-established procedure would have kicked in to prepare his body, tomb, and burial goods. The ideal period required to embalm and wrap a corpse was seventy days, the length of time that one of thirty-six constellations identified by Egyptian astronomers as circling the southern sky would spend out of sight before it reappeared on the horizon. Once wrapped up, in hundreds of metres of pure linen, the embalmed body could be kept aside indefinitely while the tomb, coffins, sarcophagus, burial shrines, and other ritual goods were prepared. Other objects that were part of a royal burial – jars of fine wine, preserved food, sacred statues, and shabti figures that stood in for the deceased – could be placed into the tomb once its rooms were ready, and those were among the first items moved into the Annex and the Treasury. The coffining, funeral procession, and further rites performed near the tomb marked the moment when the body, in its coffins, could be lowered into place in the sarcophagus and the rest of the tomb filled up around it. It will have taken several days, at least, to put everything in place, manoeuvre the lid onto the basin of the sarcophagus, and build the four gilded wooden shrines around it, one by one. The largest, which almost filled the chamber, was put together from pieces inked with assembly marks (‘south rear’) by carpenters who must have held their breath and hoped. Priests needed to perform additional prayers and actions at certain junctures, too, such as positioning objects (symbols of the god Anubis, oars, perfume vases) around and just inside the outermost burial shrine. These protected the dead king and helped him on his never-ending cycle of divine rebirth.

In the Burial Chamber itself, four magical figures were sealed up into niches in each wall, and artists had to finish painting the walls as well, before scrambling through a narrow hole left in the blocking for their exit.19 The other rooms, and all the ceilings, were left bare. Once the Annex was filled and sealed, it was the Antechamber’s turn. Three ceremonial couches were lined up against its far wall, and the last of Tutankhamun’s personal items – furniture, clothes, weapons, sticks and staves of his high office – could be fitted in around, on top, and under them. Dismantled chariots were placed in last, leaning to the left of the entrance. A drinking bowl carved from a single piece of creamy yellow alabaster, in the form of a white lotus blossom, was left standing on the floor on the way out.20 Around its rim, valuable blue pigment fills the incised hieroglyphs that wish the drinker an eternity spent ‘sitting with your face to the north wind, your eyes beholding happiness’.

Finally, the time had come to block, plaster, and seal the doorway through which, some 3,200 years later, Howard Carter would have his ‘wonderful’ view. The ancient workmen filled the corridor with limestone chips and rubble and then repeated the blocking, plastering, and sealing process to close off the entrance at the bottom of the stairs. They next filled the stairs in, too, and that was Tutankhamun buried.

As Howard Carter and his team reversed these ancient processes and began to clear the tomb, they noticed signs of rushed work, hasty adjustments (the biggest coffin had its projecting