28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

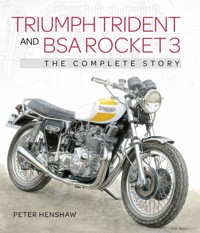

The 3-cylinder Triumph Trident and BSA Rocket 3 were developed to compete with Honda's forthcoming 750cc motorcycle. Initially they did not compare well – although very fast, they lacked sophistication and their quirky styling was offputting – and the decision was made to suspend production. This was not the most auspicious start, but a fightback was initiated and in 1971 the factory race team had a triumphant year including placing 1st, 2nd and 3rd at the Daytona 200. With over 250 photographs, the full rollercoaster-ride history of these bikes is described, including: how the bikes came to be, including a timeline of significant events; a year-by-year account of the evolution of the bikes, through the T150, T160 and Rocket 3; the story of the Hurricane; the full racing history and, finally, the Triumph 3-cylinder bikes today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 327

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Other Titles in the Crowood MotoClassics series

AJS and Matchless Post-War Singles and Twin

Matthew Vale

BMW Airhead Twins

Phil West

BMW GS

Phil West

Classic TT Racer

Greg Pullen

Ducati Desmodue

Greg Pullen

Francis-Barnett

Arthur Gent

Greeves

Colin Sparrow

Hinckley Triumphs

David Clarke

Honda V4

Greg Pullen

Moto Guzzi

Greg Pullen

Norton Commando

Matthew Vale

Royal Enfield

Mick Walker

Royal Enfield Bullet

Greg Pullen

Rudge Whitworth

Bryan Reynolds

Triumph 650 and 750 Twin

Matthew Vale

Triumph Pre-Unit Twins

Matthew Vale

Velocette Production Motorcycles

Mick Walker

Velocette – The Racing Story

Mick Walker

Vincent

David Wright

Yamaha Factory and Production Road-Racing Two Strokes

Colin MacKeller

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© Peter Henshaw 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 972 3

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Timeline

CHAPTER 1 FIRST THOUGHTS AND THE P1

CHAPTER 2P2 AND THE BOYS FROM OGLE

CHAPTER 31968–70: GOOD NEWS, BAD NEWS

CHAPTER 41971–3: FIGHTING BACK

CHAPTER 5HURRICANE!

CHAPTER 61974–5: FIGHTING ON

CHAPTER 7LAST CHANCE: THE T160

CHAPTER 8DESERT SWANSONG: T180 AND THE CARDINAL

CHAPTER 9RACING: A BLAZE OF GLORY

CHAPTER 10TRIDENT RETURNS

CHAPTER 11TRIDENT ADVENTURES

APPENDIX INORMAN HYDE: SPEED RECORDS AND LIFE AFTER TRIUMPH

APPENDIX IITHE LES WILLIAMS LEGEND

APPENDIX IIIPRODUCTION FIGURES AND DATES

Bibliography

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

‘This book would not have been possible without the help of…’ is a well-worn phrase, but it’s certainly true of this one. So thanks go to the many people who helped with research, often agreeing to phone interviews when Covid-19 made personal visits impossible.

First of all, the Trident & Rocket 3 Owners Club (TR3OC), which has collated one of the best archives of a single-model of bike I’ve ever come across. Chairman Peter Nicholls and archivist Dominic Kramer were a great help while Steve Rothera, Jerry Hutchinson and John Young kindly read the text – any errors are mine, not theirs. John also gave me access to his ‘Posh Garage’ archive, a veritable treasure trove of triple material, while many articles from Triple Echo, the TR3OC magazine, were invaluable, with authors including Tony Page, Roy Allen and Steve Rothera, amongst others.

I am grateful to the ex-Meriden, Umberslade and NVT staff who helped with phone interviews: Norman Hyde, Bob Rowley, Jim Lee, Stuart McGuigan, Bob Kemp and Ed Wright. Thanks, as ever, to Mike Jackson (for lunch as well as the information). Craig Vetter answered questions by email and sent me some of his early sketches of the Hurricane. Other pictures came from Andrew Morland, Andy Westlake, Mick Duckworth (who also allowed me to use his words on riding the rebuilt P1), John Cart and William Ball, while Steve Sewell of SRS provided some of the factory engineering drawings. Thanks to Mike Harbar for his superb drawings (www.classiclinesartist.com) and to Alan Cathcart.

Apologies to anyone I have missed – this hasn’t been one of my easiest book projects, thanks to Covid-19, but all of you really did make it possible.

Peter HenshawSherborne, Dorset, February 2021

TIMELINE

1961–2 Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele discuss the idea of a 750cc triple.

1963 Hopwood and Hele draw up plans for the bike.

1964 BSA/Triumph board gives the go-ahead.

1965 P1 prototype is registered for the road (February).

1966 P2 replaces P1. Ogle Design are commissioned to style the bike.

1967 R&D and styling continues on P2.

1968 Triumph T150 and BSA Rocket 3 are launched in September.

1969 AMA speed records are achieved (April); production pauses due to slow sales in North America (summer); Don Brown commissions Craig Vetter to restyle the triple.

1970 Production restarts (April); the ‘beauty kit’ is offered; Hurricane R&D starts at Umberslade Hall; triples place second and third at Daytona, and enjoy their first Production TT win.

1971 Triples are restyled for North American market; main US selling season is missed due to production problems; there are many race wins, including a 1-2-3 at Daytona.

1972 Five-speed version goes into full production; Rocket 3 is dropped; Hurricane is launched (September); Norman Hyde sets new world sidecar land speed record on Roadrunner III.

1973 Front disc brake is introduced for the T150V; R&D starts on the 831cc P76/Thunderbird III; NVT is formed and Meriden sit-in stops production of the T150V.

1974 T150V production restarts at Small Heath (April); R&D continues at Kitts Green on the T160 and Trisolastic.

1975 The T160 is launched with new styling, electric start and many other changes; R&D continues on the Trisolastic, 871cc T180 and Quadrent; Neale Shilton clinches a deal to export the T160 to Saudi Arabian police/army.

1976 NVT staff are sent to Saudi Arabia to assemble/test the T160s; T160 production ends (March); final bikes are sold off during 1976–7, including some Saudi-spec bikes as Cardinals; Les Williams starts building Slippery Sam replica kits.

1977 Norman Hyde develops 831cc and 975cc conversions, soon establishing Norman Hyde Ltd.

1984 Les Williams launches Triumph Legend.

1990 Triumph Trident 750 and 900 are launched as part of all-new ‘Hinckley’ range.

1994 Triumph Trident and Rocket 3 Owners Club buys the surviving P1 prototype engine and, as a long-term project, painstakingly builds an accurate replica of the complete bike.

1998 Trident 750/900 production ends.

2020 New 660cc Trident is launched. Meanwhile, BSA/Triumph triple owners are still enjoying their bikes.

CHAPTER 1

FIRST THOUGHTS AND THE P1

At that time a 3-cylinder motorcycle was a new, if not original, concept. The thought of an odd number of cylinders seemed to make most people back away, but… Mr Sturgeon quickly grasped the point and asked how long it would take to design such a unit.

Bert Hopwood

Great motorcycles would not exist without the people who have the vision, drive and practical skills to see them through to production. And there’s no doubt that the BSA/Triumph triples would never have existed without the combined talents of Doug Hele and Bert Hopwood. They made a good team – both had a strong engineering background and were steeped in motorcycling, but they also had complementary talents. When the BSA/Triumphs were launched, Hopwood had edged into upper management, having a say at boardroom level, while Hele was the archetype backroom engineer, fully focused on practical solutions and always open to new ideas.

Born in Birmingham in 1919, Douglas Lionel Hele learnt to ride at an early age and would become a lifelong motorcyclist. But his career began at the giant Austin car works in Longbridge as a draughtsman and it wasn’t until 1945 that Hele joined Douglas of Bristol, famous for its 350cc flat twins. Sadly Douglas, one of the smaller British manufacturers, was on shaky financial ground and Hele left after only a couple of years to work as a draughtsman for Norton back in Birmingham. It was there that he met Hopwood, eleven years his senior and already established as one of the industry’s leading designers.

Bert Hopwood had been in the trade all of his working life, starting out aged eighteen at Ariel and working with Edward Turner on a whole string of projects. Turner, as is well known, was something of a visionary, with an uncanny knack of knowing what the average motorcyclist wanted. He didn’t have the patience or feel for detail engineering, but that was Hopwood’s job, and the two worked well together. It wasn’t an easy relationship, but it worked – ‘dovetailing’, as Hopwood himself later wrote. That was illustrated by Triumph’s revival in the 1930s, thanks to Turner’s flair for styling and, of course, the Speed Twin.

At Norton, Hopwood and Hele soon developed a good working relationship which they would maintain for many years, right up to the collapse of BSA in 1973. So when Hopwood jumped ship from Norton to BSA (he was actually sacked), Doug Hele soon followed him to the giant Small Heath factory. The pair had a very productive time in the early 1950s, Hele penning the ohc 4-valve 250cc MC1 racer for BSA. In 1956, Hopwood took the opportunity to rejoin Norton, now as managing director, and Hele went too. There, he developed the 500 and 600 Dominator twins while Hopwood worked on opening up the big American market, which in turn led to the 650SS to challenge Triumph’s new Bonneville.

Bert Hopwood left Norton in 1961 for Triumph and, by May the following year, Hele too was looking at other jobs. The two had kept in touch, and when, in October 1962, Hopwood offered him a job in charge of development at Meriden, he decided to go. It was a good move. Not only would he be back with Hopwood, but, unlike Hele’s previous employers, Triumph were on the crest of a wave. Edward Turner had worked his magic on a range of fast, good-looking twins, built in the relatively modern factory outside Coventry. Eighteen hundred people worked at Meriden, which struggled to keep up with the booming demand. As Norman Hyde later related to author Mick Duckworth, it was a ‘busy, bustling place’, with two or even three generations of the same family on the payroll. The wage packets were generally good, which could be justified by the need to keep production flowing.

Triumph was an export-led company – any three had to be acceptable abroad.

Meriden welder as superman.

Pay may not have been quite so good in the experimental department, but, as Hyde added, they did have a string of interesting projects to work on. Many of the experimental staff – Les Williams, Alan Barrett and Arthur Jakeman, among many others – would play key parts in the story of the triple. Hyde remembers:

It was a small workshop. Small jobs were coming in all the time and there would be twenty–thirty bikes around. New ideas would come both from Doug and through the official channels. Yes, it was interesting and varied. Meriden was a short and wide pyramid – I could be sitting with Hele and Hopwood and they would ask my opinion. Your views were listened to.

Norman Hyde also has fond memories of how Doug Hele managed this team: ‘One of the nice things about Doug is that he never claimed someone’s ideas as his own, which, with his seniority, he could have done.’

It was here, in this busy and vibrant corner of the Meriden factory, that Hele and Hopwood would mastermind Triumph’s course through a very successful 1960s, sending thousands of bikes across the Atlantic every year to earn hard currency, enjoying racing success and making good profits. And of course, design the triple.

PROBLEM SOLVING

But the immediate priority was something else. Triumph’s 650 twin, especially the Bonneville, had a good reputation, but in unit construction form it had some key weaknesses that needed addressing. Doug Hele and the Meriden experimental team would solve many of these in the 1960s, leading to multiple race wins for the Bonnie, and those booming sales figures. There’s no doubt that racing really did improve the breed, with experience gained on the circuits feeding through to production. Under Edward Turner, factory support for racers had been forbidden. But he retired in 1964, replaced as managing director of Triumph by the dynamic Harry Sturgeon. Sturgeon wasn’t a motorcyclist, but he had an eye for publicity, and saw racing as key route to success in the showroom.

The Bonneville 650 was fast, but its handling needed sorting.

One of Hele’s first jobs was to sort out the Bonneville’s handling, with the invaluable help of development rider and racer Percy Tait, someone else who would be a key figure in the story of the triples. In those days, before computer-aided design and stress analysis, their methods were certainly more ‘real world’ than ‘slide rule’. Famously, one of Hele and Tait’s methods was to head out to a sweeping bend near the Meriden factory. It was fast and bumpy, a fine place to observe high-speed handling. As Percy swept past, Doug would crouch on the grass verge, concentrating on what the bike was doing. At least once he had to leap for cover when it looked like even Tait was losing control.

The upshot was a shallower steering angle of 65 degrees (from 62 degrees), which greatly improved the high-speed behaviour of the twins. Other changes, such as bracing for the swinging arm mounts and much improved damping on the front forks, helped Triumph twins gain a reputation as some of the best-handling bikes of their time. They also led to race wins in the burgeoning Production class, especially at the high-profile Thruxton 500 and the TT, as well as the 24-hour endurance event at Barcelona. Power was boosted too and, for the 1965 Thruxton, Hele coaxed the 650 twin up to 52bhp with wider-radius cam followers and linked exhaust downpipes, the latter allowing each cylinder access to both silencers, which improved torque. Nitrided camshafts and positive lubrication for the exhaust cam improved reliability, which also fed through to production. At the same time, Doug Hele and the experimental department (now effectively Triumph’s racing department as well) developed the 500cc twin into a race winner at the Daytona 500 in the USA.

BIRTH OF THE THREE-CYLINDER

There was no doubt that the 650 twin had been superbly well developed, but in terms of sheer power and stamina, it was reaching its limits. And there was no doubt that the American market, as ever, was demanding more power, preferably with a top speed of at least 120mph (193km/h). Triumph did develop a dohc 650 twin, codenamed P31 – which, despite being based on the existing pushrod engine, would have looked good on paper – but in practice it produced no more power.

The Thruxton Bonnie was an object of desire, the peak of twin-cylinder sports bikes.

With twins dominating the market, the obvious route to more power was a bigger one, and Hele and Hopwood had actually built a prototype 750cc twin at BSA in the 1950s. ‘We made one,’ he later recalled, ‘and it was very rough, they just discarded it.’ That was confirmed by his later experience with Norton’s 750 Atlas, and, in an interview with journalist Vic Willoughby in 1967, he added: ‘A high-performance 750 parallel twin is not exactly at the top of the desirability stakes.’ So if a 750 twin was too vibratory, what was the alternative?

It’s hard to say exactly when the idea of a 3-cylinder 750 first took root, but Doug Hele and Bert Hopwood, in one of their rare periods working for different employers, had kept in touch during 1962 and discussed the concept. According to Hopwood, he suggested the idea of adding an extra cylinder to the existing 500 twin to Edward Turner as early as 1961. But Turner, forthright as ever, gave it short shrift. Hopwood later write:

As far as I could gather, he simply felt that three was potty. I persisted and pointed out that a motor car which had a 3-cylinder engine had won the Monte Carlo Rally twice running; that the works tractor, fitted with a 3-cylinder engine, was performing very smoothly on the lawn outside his office window… There was not a chance of convincing Turner on this subject and I gave up.

Scott’s two-stroke triple impressed the road testers.

Meanwhile, Doug Hele, too, was thinking about three cylinders. A seminal moment seems to have occurred at the Three Counties agricultural show at Malvern in 1962, when he came across a Fordson tractor using a variant of the Perkins P3 3-cylinder diesel (see box). ‘I was listening to these 3-cylinder tractors,’ he later recalled. ‘I knew, it sounds ridiculous, that all two-strokes were even firing… it did dawn on me that it would work just the same if it was a four-stroke.’ He considered various formats, including a V3 and a 180-degree in-line engine.

So by the time Hele arrived at Meriden, the idea of a triple was well entrenched in both his and Hopwood’s thinking. In 1963, shortly after joining Triumph, Hele wrote a memo suggesting that the future Meriden range should include a moped, a scooter, a lightweight motorcycle, a 125cc dohc twin, a 250cc four and a 650 with three, four or five cylinders.

NOTHING NEW ABOUT THREE

There’s nothing new about 3-cylinder motorcycles. Commonplace now, and mainstream among small cars, they appeared to be a radical choice when the Triumph/BSA triples went on sale in 1968. But the concept goes back almost to the dawn of motorcycling – there have always been 3-cylinder bikes, though pre-Trident most were prototypes rather than production machines.

In December 1941, renowned journalist Vic Willoughby wrote a piece for Motorcycling, pondering whether the triple would ever be suitable for bikes. On balance, he thought not. While accepting that a triple would be narrower than a four, it would ultimately produce less power, would be heavier (needing a beefier flywheel) and be slightly more costly to make. But the killer for Willoughby was the out-of-balance forces caused by one piston trying to force the engine down while another (at the opposite end of the crank) was trying pull it upwards, causing vibration.

Nevertheless, he accepted that the idea had been tried several times. In 1906, the Dennell was powered by a 3-cylinder in-line JAP engine, 8hp with automatic inlet valves. The early 1920s saw the British Radial, which, as its name suggested, had three radial cylinders at 120-degree intervals. Royal Enfield later experimented with a 675cc two-stroke triple, essentially three singles joined by dog clutches. Moto Guzzi was testing a transverse dohc three intended for racing when war broke out in 1939.

Perhaps the best known of these early triples was the Scott 3S, which actually reached production in the 1930s. Scott had survived the Depression thanks largely to military contracts, one of which (though it never reached production) was for a 747cc 3-cylinder two-stroke intended as a generator. Scott’s newly installed technical director, Bill Cull, thought this would make the basis of a fine luxury tourer.

A prototype was running in 1933 and pre-launch tests by the press brought rave reviews, especially for its smooth, torquey performance – claimed top speed was 85mph (137km/h). When Scott launched the 3S in late 1934 at the London Olympia Motorcycle Show, it caused a sensation. The triple (still water-cooled) had grown to 986cc, but it clearly wasn’t ready yet, not going on sale until 1936, after four years of development. At £115, the Scott triple was very expensive and few customers were prepared to stump up for one – just nine were built before production was stopped the following year.

Could a 3-cylinder motorcycle work? Vic Willoughby was sceptical in 1941.

However, that wasn’t the end of the story. Scott’s French importer sold a couple of engines to DKW, which inspired its own F9 900cc two-stroke car engine in 1939. That would go on to power DKW, Wartburg and Saab cars after World War II.

Three-cylinder engines figured outside the car and motorcycle worlds too. As Scott was developing the 3S, a brand new company in Peterborough – Perkins – was working on a new generation of smaller high-speed diesel engines suitable for lorries and buses, and drew up a modular range with three, four and six cylinders. Perkins weren’t enamoured of threes in particular, but did want to produce a family of engines that shared the maximum number of components to keep costs down. The P3 triple didn’t actually reach market until 1951, but would sell by the thousand over decades of production, mostly for tractors. There was even a petrol version for forklifts, and it was a variant of the P3 that would catch Doug Hele’s eye in the early 1960s.

Not that he was the only motorcycle engineer thinking about threes. MV Agusta are best known for their legendary fours, but a generation of 3-cylinder racers enabled them to meet and beat Honda’s dominance of Grand Prix racing. In 1962, Honda entered the 350cc class with an enlarged version of their successful 250 four, which had already beaten MV’s 250 twin. MV’s response was an all-new across-the-frame dohc 12-valve triple of 344cc. With over 62bhp at 13,500rpm and a top speed of 150mph (240km/h), it proved a match for the Honda, especially with Giacomo Agostini on board. In fact, it proved to be as quick as MV’s 500cc four, and with a better power-to-weight ratio to boot.

Ago and the new triple made a fairytale debut at the German Grand Prix in May 1965, battling with Honda team leader Jim Redman before the latter fell off – the MV went on to lap the entire field, including Ago’s team mate Mike Hailwood. Agostini and the MV triple (now enlarged as a full 500) took the blue riband championship in 1966, 1967 and 1968, all before the BSA/Triumph triple went on sale.

Of course, MV never built a 3-cylinder bike for the public, but Kawasaki did. The famous (or infamous) H1 two-stroke triple was launched in 1968 and, like the BSA/Triumph, was intended to rival the Honda CB750. The Kawasaki engineers had been quick off the mark – their project had only been given the green light in June 1967 – and the 500cc H1 was claimed to be the fastest road bike in the world. Some might have disputed that, but Kawasaki’s triple did build up a fearsome reputation for wild performance which at first wasn’t matched by its handling. Suzuki built a two-stroke triple as well, but its GT750 was very different – water-cooled, much heavier and intended as a smooth, relaxed tourer. A little while later, Laverda came along with the solid, fast Jota, a one-litre dohc triple with high-speed stamina.

By the early 1980s, all of these had faded away, as the market focus turned to 4-cylinder sports bikes. It wasn’t until 1991 that the 3-cylinder motorcycle began its revival, thanks to the reborn Triumph at Hinckley.

Royal Enfield built this in-line three.

In practice, the Scott 3S’s high price put customers off.

First Designs

With Edward Turner still at the helm (though now contemplating retirement), there was little chance of this becoming an official project, yet Hele and Hopwood drew up plans for what a Triumph 750 triple might look like. The quickest and easiest route was to use the existing 500cc twin architecture with an extra cylinder added on, so one evening in late 1963, sitting in Doug Hele’s office, that’s what they did, though using the pre-unit long-stroke dimensions to keep the three’s width to a minimum. The unit 500’s oversquare dimensions of 69 × 65.5mm would have made the triple wider and, in a market used to twins, it was clearly thought essential not to scare buyers off with anything too bulky. Instead, this drawing board concept used the old pre-unit 500 twin dimensions of 63 × 80mm, which gave an unfashionably long stroke but helped keep width to a minimum. A 120-degree crank was settled on, to give even firing pulses, but otherwise this sketched-out triple was familiar Triumph fare, with vertically split crankcases, gear-driven inlet and exhaust camshafts controlling shortish pushrods and two valves per cylinder.

But it was still only on the drawing board, and there it might have stayed if Edward Turner had decided to hang on to his hands-on role. As it was, he announced his retirement in early 1964, and the hunt was on for a replacement as chief executive. Hopwood was dismayed to learn that the BSA board had appointed someone from outside the industry, and it would become a bête noire of his that knowledgeable staff within the industry were passed over for top management in favour of newcomers.

In Harry Sturgeon’s case, though, it looked like a good choice. Although not a motorcyclist (he had worked for De Havilland aircraft before becoming MD of the Churchill Grinding Machine Company, a BSA subsidiary), Sturgeon possessed an energy and dynamism that arguably had been lacking at the top of the BSA/Triumph empire for some time. With a reputation as a super salesman, he would oversee a dramatic increase in production at both Small Heath and Meriden to keep up with booming demand in the USA. Bert Hopwood, despite his first misgivings, soon warmed to the energetic Sturgeon, who was open to new ideas as well as being a good listener. As a chief executive, Harry Sturgeon had his faults, tending to focus on increasing production at the expense of spares supply, among other things, but there’s no doubt that he was a breath of fresh air.

That became clear at a top management meeting called to introduce him to all the senior managers, which has gone down in history as the most crucial meeting ever for the triple. It was a big affair, with about thirty top brass in attendance and, according to Bert Hopwood, lasted several hours, with a lot of discussion. Everyone was just about to file out of the room when one of the sales managers, almost as an aside, mentioned to the chairman that Honda would ‘shortly’ be launching a 750. Everyone came back to their seats.

This was big news, because the assumption until then had been that the Japanese would concentrate on smaller bikes, leaving the British industry to build bigger machines with fatter profit margins. According to Hopwood, the reconvened meeting went quiet before Harry Sturgeon turned to him, as the company’s top engineer, for an answer. Bert, of course, was not fazed, explaining that a 750 twin would be too vibratory, and that a balancing device would take too long to develop. A triple on the other hand, would be smoother, narrow enough to be acceptable and would fit a modified version of the Bonneville frame. But this idea didn’t get a fairytale reception. As he later wrote:

Most of those at the meeting seemed to feel that I was sickening for something serious, for at that time a 3-cylinder motorcycle was a new, if not original, concept. The thought of an odd number of cylinders seemed to make most people back away, but not so Mr Sturgeon, for he quickly grasped the point and asked me how long it would take to design such a unit.

This was Bert Hopwood’s cue, for he was able to produce his trump card – that they already had such a design drawn up and just needed the go-ahead to make the first prototype. This was swiftly agreed. Ever cautious, Hopwood would not be drawn on exactly how much smoother than a twin the triple would be – that would have to wait for a running prototype. He also stressed that the new engine, based as it was largely on the twin-cylinder architecture, should only ever be seen as a stopgap – something to compete with Honda’s 750 until an all-new design was ready.

P1: THE FIRST PROTOTYPE

They quickly got to work. Draughtsman Harry Summers got busy on detail work such as the oil pump, which was driven from a vertical shaft off the inlet camshaft. The upper part of this shaft was also used as the distributor drive – for the prototype, this was from a 6-cylinder car, with every other post taken out, while the contact breaker itself (with just one set of points) was driven off the exhaust camshaft. To get a running machine as quickly as possible, lots of standard parts were used, including the Bonneville gearbox and clutch. There was enough space between the gearbox sprocket and the back of the usual clutch position to move the clutch there, which had the benefit of narrowing the width between the footrests. A gear primary drive (‘for the sake of being modern’, according to Doug Hele) replaced the usual chain. The crankcase, in three sections, was sand cast and of course vertically split.

The prototype triple was up and running relatively quickly.

The TR3OC’s restored P1 later went on display at the National Motorcycle Museum.

The various parts were made and assembled, and test bed results showed great promise, the new engine producing 58.5bhp at 7,250rpm, though there were signs of overheating. There was clearly some urgency about the project, because the triple was soon mounted in a modified Bonneville frame and registered for the road on 5 February 1965 (frame number 65/750/1). The end result had many differences from the production triple, including twin-style rocker boxes, part-circular webs on the crank, the oil pump position and a cast-iron barrel. By now it also had a code name – P1.

At last the great day came when Triumph’s first triple would move under its own steam. Les Williams later recalled that most of the experimental staff had gathered to watch, including Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele. The bike fired first kick and Harry Wooldridge revved the engine, only for the gear primary drive to set up a tremendous clattering. ‘Apparently we were not very good at making straight-cut gears,’ said Les.

The P1 was a mixture of old and new parts.

Still, the important thing was that Experimental had a running prototype and could get on with the serious business of testing it. Naturally the test riders were keen to have a go, and Les Williams remembers riding the prototype around the factory site, including a road at the back, which narrowed between two buildings. Blasting the triple through the narrow space, he was treated to that famous howl, which annoyed the workers on either side but underlined one of the bike’s most distinctive (and enduring) features. Apparently a 180-degree crank version was tried, but it gave a less pleasing note, like a 4-cylinder engine with one pot not firing.

Norman Hyde remembers his first sight of the P1, underlining that despite the team’s efforts to keep it narrow, it was still a far bigger beast than the twins most riders were used to. ‘The triple looked so big and heavy when I first saw it,’ he said. ‘But I enjoyed riding them – they seemed big but we would always nail them in testing, with two-position throttles (off, or full on). When testing there’s no point in doing anything less.’ Jim Lee, another ex-Meriden man, also remembered riding the P1. ‘I thought it handled like a piece of string, but the power-to-weight ratio was very high. The production frame, which Doug Hele had a lot to do with, was much better, because Doug was brilliant at sorting frame problems out.’

ON THE ROAD

Once out on the road, those early signs of overheating reappeared, with different temperatures between the cylinders – one measurement at 7,000rpm on the exhaust rocker box showed 140ºC (284ºF) on the centre cylinder and 200ºC (392ºF)on the right-hand one, while the centre downpipe was glowing red. The test riders loved the performance and the fact that the bike was so smooth at high revs, though there was a vibration period at 4,500rpm. The primary rattle was reduced (but not eliminated) by fitting a larger intermediate gear, though this gave an audible whine until the engine warmed up. Initially the carburettors were controlled by three separate cables, which not only made for a heavy throttle but put the carbs out of synchronization as the handlebars were turned, changing the radius of the cables. The answer was a single cable to a junction box.

Doug Hele’s goal was to minimize the triple’s width, and he succeeded.

The prototype triple was being tested on the road by early 1965.

Meriden was only a few miles from the M1 motorway, which was a convenient place for high-speed tests in the days before the 70mph (113km/h) limit, and riders were able to keep up three-figure speeds, though on one 120mph (193km/h) run Harry Wooldridge noticed that the oil in the tank was actually starting to boil, which obviously wouldn’t be good for bearing life. Bert Hopwood suggested a cast aluminium oil tank with external finning, though this made little difference.

Then Harry Wooldridge mentioned an oil cooler, as used by the VW Beetle engine. It so happened that a friend of his was a VW dealer, so he nipped round there and asked to borrow a cooler. Sited next to the timing cover, it didn’t look pretty but did the job. ‘It looked awful but it worked,’ remembered Harry, ‘and no matter how hard the bike was ridden the oil stayed within acceptable limits.’

Jaguar Cars, of course, were just up the road from Meriden and they too used the M1 for high-speed tests. Harry came back from one run having been doing battle with a test Jag; back at Meriden, Doug Hele asked what rpm the bike had been pulling in top gear, got out his slide rule and worked out a speed of 124mph (200km/h). As for the oil cooler, that was swapped for a Mini Cooper unit, which was found to have the least resistance to flow and best effect on cooling.

Early Problems

So the performance was exciting, but teething troubles were coming thick and fast. Not only did that bigger intermediate gear in the primary drive whine until it warmed up, but the primary gear bearings wore out quickly. Needle-roller bearings helped, but then the casings proved inadequate. The multi-plate Bonneville clutch was unable to cope with the triple’s power, and clutch slip was found to have been caused by the bonded plates’ driving ears being ripped off. All these issues would be solved as the R&D went on and P1 became P2, but in the meantime the clutch was an Achilles heel. One day the workshop were told that a delegation of police would like to see Triumph’s exciting new prototype. The clutch was dismantled at the time, but the fitters were able to quickly find enough clutch parts to get the bike going again. It held together for demo ride, but the police weren’t impressed by that noisy primary drive.

Amal Monobloc carburettors and twin-style rocker boxes marked the P1 out from later prototypes.

Other troubles were scarier, as the P1 had a tendency to catch fire. Three Amal Monoblocs were fitted, the outer two float chambers being removed and the centre chamber supplying all three carbs. It sounded neat, but when the centre chamber was tickled for starting, excess fuel could drip down onto the distributor. The bike once caught fire while Doug Hele was riding it into work one morning. Thinking quickly, he stopped and extinguished it with water from a nearby horse trough, and only the paint was singed. There were also problems with fuel frothing, something cured by mounting the Amals on a manifold, in turn mounted on the head by rubber hose to metal stubs.

The P1’s crankcases were the same style as the 650cc twins, and the close fit of the triple’s crankshaft meant there was no room for oil to sit at the bottom of the case before being scavenged. Instead, it was picked up by the crank and hurled around the engine, blowing it out of the breather tube, and an engine test in July 1965 mentioned this happening at high revs. A more generous sump cured that. The P1 engine also suffered from high oil consumption; various different sets of scraper rings were tried, but it was always a compromise between scraping and bore wear. Eventually it was found that the bores needed a certain amount of roughness to hold the oil and prevent scuffing during running-in.

Some changes didn’t reach production, such as the rockers with a ball-ended adjuster over the pushrod and a radius pad over the valve, in an attempt to lessen valve head indentation, which it did. Another idea was the use of self-locking nuts on the bearing caps, purely as an aid to the production process. Alan Barrett looked into it but found that the extra torque needed to overcome the nut’s friction caused the bearing shell to distort and lose its roundness. There were also main bearing failures as the mileage mounted. The bearing supplier (Vandervell) blamed this on sand left from the aluminium casting, but it was found to be down to the traditional white metal, which couldn’t cope with the higher revs and loadings of the triple. Lead-bronze bearings (another Mini Cooper contribution) were the answer, first with the Mini items, then Ford Cortina big-end shells used in the triple’s main bearings by grinding the crank journals down by two thou and enlarging the bearing housing slightly.

The Trident & Rocket 3 Owners Club made a superb job of restoring this P1.

One major and recurring problem was the seal between the cylinder head and barrel. There were different expansion rates between the P1’s cast iron barrel and its alloy head and crankcases as the engine heated up and cooled down. This meant oil leaks between head and barrel, and head gasket creep, as Norman Hyde remembered.

The first gaskets were of steel, but they didn’t seal as well as they should. Various things were tried – dowels to locate the gasket, and a wire mesh type of gasket with a metal ring to seal around the bore. With the ring, bare wires would be exposed to the bore and glow red hot.

An alloy barrel promised to cure all of this, with the bonus of better cooling and a weight saving thrown in. Of course, an alloy barrel needed liners, and the cast iron liners tried first didn’t work, again because of different expansion rates causing them to come slightly loose in the barrel when hot, allowing oil into the tiny gap. This could be cured with an interference fit, but this in turn caused the outer barrel and liners to distort. Austenitic liners would be the eventual solution, as their expansion rate was closer to that of the alloy barrel. The same was true of the cylinder head bolts. Steel bolts expanded less than the barrel, which compressed the gasket, and as the barrel cooled again, the torque on the bolt was lost. Austenitic bolts cured the problem.

There were electrical puzzles to solve too. Several types of coil were tried before the best was arrived at (the Lucas HA12). More mysterious was the tendency for Lucas alternators to lose their charging ability on the triple after about 1,000 miles (1,600km). Development engineer Alan Barrett was given the job of finding out why, and discovered that metallic debris was collecting in the spare holes in the stator insulating cheeks. When the alternator was working hard, magnetic flux was compressing this debris and causing a short circuit to earth. It was a difficult one to solve because when the engine stopped and cooled down, the debris expanded and the problem apparently disappeared. Encapsulating all the alternator coils in resin was the cure.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE P1?

Factory prototypes, the result of so much work and scrutiny at the time (and renewed historical interest a few decades later) are often forgotten in the meantime, or simply scrapped. Over fifty years later, it seems hard to believe that such a landmark machine as the P1 nearly suffered that fate, but of course to Meriden it was just another job, and they had plenty of other things to think about. But happily, one of the P1 engines did survive. Better still, in the 1990s, the Trident and Rocket 3 Owners Club rescued it, restored it and built it back into a running machine.

Could the P1 have gone into production in 1966? The truth was it needed more development.