28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

This is the ultimate book for any enthusiast or professional who is tuning or modifying the Rover V8 engine. This essential read covers all aspects of tuning this versatile and much-loved engine, with an emphasis on selecting the correct combination of parts for your vehicle and its intended use. Topics cover the short engine; cylinder head modifications and aftermarket cylinder heads; camshaft and valve-train; intake and exhaust systems; cooling system; carburettors and fuel injection; distributor and distributor-less ignition systems; engine management; LPG conversions and, finally, supercharging and turbo-charging.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 449

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

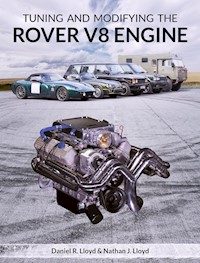

TUNING AND MODIFYING THE

ROVER V8 ENGINE

TUNING AND MODIFYING THE

ROVER V8 ENGINE

Daniel R. Lloyd & Nathan J. Lloyd

First published in 2019 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2019

www.crowood.com

© Daniel R. Lloyd and Nathan J. Lloyd 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 604 3

Frontispiece: Rover V8 engine with Wildcat cylinder heads and modified Pierburg injection manifold. ANTHONY DOWIE

CONTENTS

Dedication and Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.Engine Requirements and Specification

2.Short Engine

3.Oil System

4.Cylinder Heads

5.Camshaft

6.Valvetrain

7.Intake System

8.Exhaust System

9.Cooling System

10.Fuel System

11.Ignition System

12.Engine Management

13.Liquid Petroleum Gas

14.Forced Induction

Appendices

Engine numbers

Camshaft identification

Index

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to Russell Robert Lloyd, who shared his passion and knowledge of the Rover V8 engine with us.We will always love you Dad.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals for helping us produce this book:

Alex Cochrane (Killerbytedesign), for the cover design and assisting with photographs.

Roland Marlow (Automotive Component Remanu– facturing Ltd), for providing technical advice and supplying photographs.

Sally Lloyd, Wendy Chard, Sandra Lloyd, Jason Starkings, Paul Brooks and Martin Howlett, for assisting with proof-reading.

Steve Cliff and Rob Steele, for assisting us with our Rover V8 development work.

Mark Everett, James Perkins (oldsmobilejetfire. com), SC Power, Eann Whalley (Torque V8), Rotrex AS, Patrick Stuart and Derek Beck, for supplying photographs or illustrations.

INTRODUCTION

The Rover V8 has been around for many decades now, and a few books have already been written about this very versatile and well-loved engine. The aim of this book is to provide the reader with a complete and comprehensive guide to tuning the Rover V8 engine. Although designed in the late 1950s and last produced for production vehicles in 2002, the Rover V8 engine lives on into the twenty-first century in the hands of many owners of classic and competition vehicles. Enthusiasts and specialists alike have developed the engine even further now, with modern engine management, supercharging, turbocharging and LPG conversions becoming much more commonplace in recent years.

In its original form as a Buick or Oldsmobile 215 V8, this engine powered hundreds of thousands of American cars. Various circumstances then led to the engine design and original tooling being sold to Rover in 1965, and the engine we know and love as the ‘Rover V8’ was born. First featured in the Rover P5B, the Rover V8 has gone on to power a huge range of vehicles, including the Rover P6, Rover SD1, Triumph TR8, Land Rovers, Range Rovers, LDV Sherpa, as well as various TVRs, Morgans, Marcos, Westfields and many more besides. This means that there are still a large number of vehicles around today that are powered by the legendary Rover V8 engine.

Nowadays the Rover V8 is naturally compared to more modern engines when considered as a transplant option for an engine conversion or kit car. Some people will therefore disregard this V8 engine as being relatively low on power compared to its cubic capacity, but when you also consider the relatively low weight and compact size of the Rover V8, it is easy to see why it is still a popular choice with car enthusiasts today. If you then factor in the glorious sound and the versatility of its broad spread of torque, it is clear that there is still life in the old engine yet!

MG RV8 engine bay.

Morgan Plus 8.

TVR Chimaera 400 on track. MARK EVERETT

Workshop manuals.

1954 Ferguson tractor with 3.5-litre Rover V8.

Ultra 4 buggy with 4.6-litre Rover V8.

This book is not designed to replace the original workshop manuals for this engine. There are already excellent factory workshop manuals readily available from Land Rover for the sole purpose of stripping and reassembling the Rover V8 in its standard specification. Although there will be some overlap in information, the main purpose of this book is to provide the reader with all the information required to tune and modify the Rover V8 for their particular application. Although this book is written in a manner that allows you to read it from cover to cover, each chapter or subsection can also be used as a standalone reference. If used in this manner it is important to bear in mind that the different engine components need to work together properly in order to produce an engine that best meets your requirements.

The versatility of this marvellous engine makes it suitable for a very wide range of vehicles, from lightweight sports and race cars, to 4×4s used for towing or specialist off-road competition. This book should enable the reader to build or modify their Rover V8 engine to best suit their vehicle and its intended use. Although the engine is fairly versatile in most forms, tailoring it correctly for the application will yield significant benefits to the end user.

Ford Capri with 3.9-litre Rover V8.

Mercedes 190e with 4.6-litre Rover V8.

CHAPTER 1

ENGINE REQUIREMENTS AND SPECIFICATION

Before deciding on the specification of your engine build, or spending money on your existing engine, it is important to decide exactly what you require the engine for, and which characteristics are particularly important to you. By establishing your requirements at the beginning you will spend less of your hard-earned cash reaching your goal than if you change the requirements over the course of building or modifying your engine.

Be honest with yourself about your requirements. What are your priorities and where are you willing to compromise? Is maximum performance your main priority? Do you require good performance but also reasonable fuel economy and reliability? Does your engine have to meet certain emissions criteria? Is your vehicle likely to suffer from traction or transmission limitations? All engine specifications involve compromise in one or more areas. The aim is to balance these various compromises to suit your needs.

Planning your engine build carefully is also essential to ensure that you do not mismatch the various components: for example, spending money on big-valve cylinder heads but fitting an intake manifold that will not allow the heads to flow to their full capability; or fitting heads, intake and valvetrain that are capable of producing power up to 7,000rpm, but being limited by a crankshaft that will break at 6,200rpm. This may seem obvious, but many of us (authors included!) have been guilty of building or modifying engines in this way, costing more time and money in the long run to achieve the same desired result once the various limitations have been resolved.

PERFORMANCE

You have to be truthful with yourself about the type of ‘performance’ you require. Is there a particular peak horsepower figure that you are looking to achieve on the rolling road? A quarter-mile time you are looking to obtain? Or are you after the most significant ‘seat of the pants’ improvement within a given budget or specification?

Measuring the performance of an engine is a controversial topic and far from straightforward. This performance is usually measured whilst the engine is still in the vehicle, using a chassis dynamometer, drag strip, stopwatch or accelerometer. Measuring engine performance in the vehicle will obviously introduce a lot of potential for error, through transmission losses, rolling resistance, traction issues, driver reaction time, gear ratios, vehicle weight and aerodynamics. These errors must be correctly calculated to ensure an accurate measure of engine performance. A properly calibrated engine dynamometer is therefore a more accurate way of measuring the performance of the engine, with the torque being measured directly at the flywheel or crankshaft.

More often than not people focus on the peak horsepower or peak torque, but 99 per cent of the time the engine is not operating at this point, even when at full throttle. Unless we are purposely building a circuit-spec race engine with a narrow power-band, what we should focus on is the torque at the point you fully open up the throttle, until the point you let it off. Most drivers will be able to drive faster with an engine that has a broad spread of torque (a ‘rally-spec’ engine) than they would with the circuit-spec engine, even if the circuit-spec engine has more peak horsepower. The engine with the broad spread of torque will always feel more powerful, even to a racing driver.

Dyno screen showing ‘before’ and ‘after’ tuning.

Rover V8 on engine dyno. ROLAND MARLOW, AUTOMOTIVE COMPONENT REMANUFACTURING LTD

Deciding the engine speed range in which you want most of the torque (and by extension horsepower) to occur is a key part of the engine specification. The Rover V8 has a relatively ‘flat’ torque curve, but can be tuned for higher rpm torque if the engine builder is willing to sacrifice some lower rpm torque, drivability, and engine longevity. Likewise, if the application requires additional low rpm torque (for example off-road, towing) the Rover V8 can be tuned to suit if you are willing to sacrifice some higher rpm power and drivetrain longevity.

The weight and available traction of the vehicle being used also plays a key part here. With a lightweight sports car or kit car (for example TVR, Marcos, Westfield) not only is it acceptable to sacrifice some lower rpm torque for higher rpm power, it is often advantageous, as the Rover V8 usually endows these vehicles with an excess of torque at lower engine speeds. This leads to traction issues, making it difficult for the driver to consistently extract the maximum performance out of the vehicle at lower engine and vehicle speeds.

Another consideration is the speed at which the engine itself is able to accelerate. Factors such as low reciprocating assembly weight, low frictional losses, lean-best torque fuel mixture, optimum ignition timing, optimum valve timing and high port velocities all help the engine’s reciprocating assembly to accelerate quickly through the rpm range. Interestingly the Germans have a single word that best describes this: Beschleunigung-sleistung, which means ‘acceleration power’. An engine might have a high horsepower or torque figure – at, say, 5,000rpm – but if it takes twice as long for the engine to accelerate to that engine speed it will not perform so well in real-world terms.

Chassis Dynamometers

Most of us will use a chassis dynamometer (aka rolling road) to measure the performance of our Rover V8-engined vehicle. Many of us are aware that horsepower and torque figures not only vary between different cars, but also between different dynamometers, so we will briefly discuss some of the different methods of measuring horsepower and torque via a dynamometer to try and get a better understanding of what it all means.

The definition of horsepower is well publicized, but it is still worth printing the formula here to remind us that horsepower is a function of torque and engine speed:

Torque is the direct force that the engine applies to the drivetrain, or the direct force that the wheels apply to the ground – we will look at the differences later. Horsepower is usually more relevant to us, as this is a measurement of the work done by the engine or wheels in a given amount of time – this governs the rate of acceleration.

Car manufacturers usually always quote horsepower and torque figures at the engine’s crank or flywheel; this is measured directly with the engine on an engine dynamometer. During testing some car manufacturers will use an engine that has been built to a better standard (blue-printed) and will not fit various ancillaries (including alternator, power-steering pump, and so on) to give higher publicized performance figures – TVRs of the 1990s are a prime example of this. Unfortunately there is not just one dynamometer measurement standard, either: common standards currently used include DIN 70020, SAE J1349, ISO 1585, and more besides. Different standards will give slightly different horsepower and torque figures, so it can be seen that there is already considerable variation between different horsepower and torque figures, even when measured directly at the flywheel or crankshaft.

V8-powered Westfield.

Westfield with 4.3-litre Rover V8.

There are a few commonly used methods for estimating transmission losses, but as described, they are just estimates, adding even more variability between different rolling-road figures.

Many rolling-road operators will apply a transmission correction factor, in the form of a simple percentage multiplier, to the wheel horsepower and torque figures in order to provide the customer with flywheel horsepower and torque figures.

Some rolling roads do attempt to calculate transmission losses by measuring the horsepower used during a ‘coast-down’ phase, but this is still not accurate, as the losses are being measured with the gears within the differential and gearbox loaded on the opposite side to when the transmission is under maximum load in the forward direction. Interestingly, when we were using a local eddy-current type of rolling road we consistently recorded coast-down losses of about 45bhp at peak horsepower on a wide range of two-wheel-drive TVRs with a range of different manual transmissions, regardless of actual engine output. In other words, a TVR with 200bhp had virtually the same transmission losses as a TVR with 400bhp. This completely contradicts the idea that transmission losses are a simple percentage multiplier – if this is the case, then the TVR with 400bhp will have double the transmission losses of the TVR with 200bhp.

Perhaps it is more likely that a large proportion of the transmission losses are essentially a fixed amount with a small percentage variation to account for increased frictional losses with increased horsepower and engine speed.

TVR Chimaera 400 on Sun rolling road.

TVR Chimaera 400 on Dynapack hub dynamometer

TVR Griffith 500 on Dastek rolling road.

Supercharged TVR Chimaera 400 on Dastek rolling road.

The only way to know truly which method is correct would be through extensive testing. Despite numerous pages on the internet about dynos and transmission losses, such test information remarkably appears to be non-existent. In an ideal world we would test the engine on an engine dynamometer with all the ancillaries fitted (including complete intake and exhaust systems), and then test the car on a hub dynamometer (rather than a conventional rolling road) to measure the wheel horsepower without any variances due to tyre pressure, traction or ratchet-strap tension. If done using the same measurement standard, this would give us the most accurate measurement of transmission losses across the entire speed range.

Another consideration when comparing any dyno results is the effect of various atmospheric variables – this includes intake air temperature, ambient air temperature, barometric pressure and relative humidity. The performance of the engine will vary according to these atmospheric variables, so the dynamometer software will use various sensors to monitor these variables and calculate corrected horsepower and torque figures. The way in which the software calculates and corrects the effect of these atmospheric variables is dictated by the test measurement standard used (for example DIN 70020, SAE J1349, and so on). Unfortunately, even when using the same measurement standard, the results can vary (or can even be fiddled) by the location of the sensors – the location of the intake air temperature sensor in particular can cause a significant increase or decrease in calculated horsepower and torque.

TVR Griffith 500 on Dynapack hub dynamometer.

Dynapack software on screen.

So to summarize, chassis dynamometers are primarily useful for engine calibration (mapping), tuning and diagnostic purposes, not for comparing horsepower or torque figures between different dynos and cars. There are so many variables that we would be best to disregard flywheel horsepower altogether, and look solely at wheel horsepower – this way we remove the largest variable of all.

Although not commonly used by anyone outside professional engineering or race teams, there are a number of other ways of measuring or comparing engine performance. Some of these are slightly theoretical but can be useful when designing a new engine specification, comparing different engine specifications, or establishing whether the claimed performance of a particular engine specification is realistic.

Volumetric Efficiency

Volumetric efficiency is basically a measurement of how effectively the engine’s cylinders are filled during a complete engine cycle (two rotations of the crankshaft). An engine that is operating at 100 per cent volumetric efficiency (VE) at a particular engine speed is effectively filling its cylinders completely during each engine cycle. By plotting a graph of volumetric efficiency against engine speed we can see at which engine speeds the engine design is most efficient. Assuming that the fuel mixture and ignition timing have been fully optimized, the volumetric efficiency curve will be a similar shape to the engine’s torque curve, with peak torque occurring at the engine speed at which peak volumetric efficiency starts to occur.

If the fuel mixture at maximum engine load is the same throughout the entire engine speed range, then the programmed pulse width of the fuel injectors will also plot a curve of similar shape.

Another parameter that corresponds directly to engine torque and volumetric efficiency is mass airflow. If the engine is fitted with a mass airflow meter, then measuring the mass airflow at maximum engine load throughout the engine speed range will also give a similar shaped curve and is therefore an excellent indicator of engine torque.

For the Rover V8, peak volumetric efficiency values are typically between 80 and 90 per cent. With aftermarket cylinder heads and careful selection of the other engine components it is theoretically possible to achieve a peak volumetric efficiency of more than 100 per cent, although this is very difficult to achieve in practice.

Graph showing the relationship between volumetric efficiency, mass airflow and torque.

Brake Mean Effective Pressure

Brake mean effective pressure (BMEP) is the mean average pressure to which a piston is subjected during one complete down-stroke (that is, from TDC to BDC). This measurement can be calculated from the torque output and the engine’s displacement. Therefore it is useful when comparing Rover V8 engines with different capacities to ensure that the alleged power outputs are realistic with the components fitted.

For the Rover V8 engine, BMEP values at the engine speed at which peak horsepower occurs are typically between 130 and 170psi, depending on the state of tune of the engine. As an example of a high-output Rover V8 engine, a 5-litre Rover V8 putting out a genuine 320bhp at 4,750rpm will have a BMEP value of 175psi.

With aftermarket cylinder heads and careful selection of the other engine components it is theoretically possible to achieve BMEP values of 200psi, although very difficult to achieve in practice.

DRIVABILITY

Drivability is difficult to quantify, but anyone who has driven a badly tuned Rover V8 with an aggressive camshaft will know all about poor drivability! Although this is particularly important for road-going vehicles, it should still be a consideration for competition vehicles as well. In many cases this is due to incorrect ignition timing, incorrect fuelling, or faulty components, but poor component choice can also be the cause of a Rover V8 engine that has flat spots in its power delivery.

As the Rover V8 engine is so cylinder head restricted as standard, it is fairly common practice to fit a camshaft of much more aggressive profile to try to achieve a particular horsepower target, by effectively opening the valves for longer in an attempt to overcome the head restrictions. In many cases this is a compromise too far, and the fact that the valves are open for longer makes the engine lose a great deal of cylinder pressure at low engine speed conditions. This low cylinder pressure means that the engine has distinctly less torque at lower engine speeds, and might even struggle to idle properly at a normal idle speed. An engine fitted with such a camshaft will have a noticeable flat spot at the lower engine speeds, and when the engine does ‘come on song’ there will be a noticeable switch in behaviour and engine output. This type of engine does not have a smooth transition in power output with increasing rpm, and will be difficult to drive at low vehicle speeds.

In many cases the Rover V8 owner will select a camshaft that has too much overlap and too much lift for the application – in some instances we have even obtained more power and torque by ‘downgrading’ the camshaft!

RELIABILITY/ LONGEVITY

It is easy enough to build an engine that produces a lot of power and torque for a short amount of time, but much more challenging to build such an engine that will last 100,000 miles (160,000km) or more. Again, component selection plays a big part here, and there is usually a compromise to be made between performance and longevity in particular. Going back to the camshaft as an example, a high lift camshaft will provide more horsepower, but there will be a substantially increased load on the valvetrain, significantly reducing the life of the camshaft, followers, rocker gear and so on. The high lift camshaft may even ultimately lead to the failure of the short engine.

Naturally, good quality components should always last longer than cheap components, and it is always worthwhile doing your research before purchasing engine components. Certain markets (for example, the Land Rover aftermarket) are very price driven, and as a consequence a number of components within that market are of a sub-standard quality.

Regular service intervals are very important if you want your engine to last a decent amount of time, with regular oil and filter changes being a minimum requirement. The air filter is a service item that is often neglected, and this should be replaced or cleaned/oiled as part of an annual service regime.

Engine oil and oil filter.

A well built and regularly serviced Rover V8 engine is likely to last an appreciable length of time. These engines can easily cover more than 100,000 miles (160,000km).

FUEL ECONOMY

Economy is not a word usually associated with the Rover V8, but a number of ways can be employed to improve significantly the fuel economy of these engines. These include camshaft selection, cylinder head modifications, optimizing ignition and airfuel mixture, increasing compression ratio, and the use of alternative fuels. The various methods will be discussed in the following chapters, but again, if you want the best fuel economy, it is important to choose carefully the components and/or modifications to best suit your fuel economy target.

Measuring fuel economy is much more straightforward than measuring performance: it is simply the ratio of distance covered for a given amount of fuel, or vice versa – for example, miles per gallon (mpg) or litres per 100 kilometres (ltr/100km). To enable us to measure fuel economy we simply need an accurate odometer, usually a part of the vehicle’s speedometer, and an accurate measure of fuel used. Modern cars often already have a built-in fuel economy display, so you don’t even have to do the basic maths to work out the fuel economy.

It is worth noting that certain aspects of both performance and economy tuning work hand in hand – for example, optimizing the compression ratio, fuel mixture and ignition timing will improve both engine performance and fuel economy, whilst other aspects are mutually exclusive. Camshaft selection is a good example of an area where a compromise is made to suit the end user’s requirements – one particular camshaft will provide relatively good fuel economy but have very poor top-end performance, whereas another camshaft will give much better top-end performance but with poor fuel economy and idle quality.

SUMMARY

It is easy to assume that the original engine or vehicle manufacturer did not select the best components, but in many cases they actually selected the best combination of engine components for the application, with a well thought out compromise between reliability, drivability, fuel economy, emissions, performance and cost. Changing one of these components for an ‘upgraded’ item can adversely affect this optimized combination, so that you may have gained a little performance, for example, but to the significant detriment of the other factors – namely reliability, drivability, fuel economy and emissions. If you had fully understood that this was going to be the case beforehand, you may well have decided that the little extra performance was not worth the sacrifice!

The aim of this book is to provide you with the information to understand fully the Rover V8 engine, so that you can carefully build or modify the engine that will suit your application best.

CHAPTER 2

SHORT ENGINE

The Rover V8 engine block is a compact aluminium design, with steel liners and a single camshaft located between the two cylinder banks. Apart from being largely aluminium, it is similar in design to many classic American V8 engines – including the Chevy small block. This is not surprising when you consider that the Rover V8 originated from the Buick and Oldsmobile 215 V8 engines.

This chapter will look at the various Rover V8 short engines that are available, and how to select the ideal one for your application. This will cover the engine block, crankshaft, pistons, piston rings, conrods and bearings.

ENGINE BLOCK

A range of different capacity Rover V8 engines is available; the standard Rover/Land Rover ones are as shown in Table 1.

There is also a wide range of alternative capacity Rover V8 engines that have been made throughout the years; Table 2 lists a selection of them.

A number of slight variations of these engine capacities are also available, depending on the specific over-bore chosen. For example, a standard 4.6 (4553cc) with a 0.5mm over-bore (94.5mm bore) will give a capacity of 4601cc.

Table 1: Standard engine capacities

Table 2: Alternative engine capacities

If you are trying to decide on a specific engine capacity for your particular application there are a number of factors to consider:

Torque requirements/limitations: How much torque do you require for your particular application? The larger capacity Rover V8s produce fairly significant amounts of low-down torque. This is usually beneficial, particularly for 4×4 applications, but can be a disadvantage if the vehicle is particularly light and lack of traction becomes an issue. Is the existing drivetrain capable of handling the torque level of your chosen engine capacity? Can you afford to replace and upgrade the drivetrain components to handle the torque of your chosen engine capacity?

RPM requirements/limitations: Choosing an engine with a longer stroke will limit the engine’s maximum reliable rpm limit. For example, 6,000rpm should be considered as the maximum safe rpm limit for a TVR-spec 5-litre with its 90mm stroke. Increasing the stroke for any given engine speed will consequently increase the piston speed. Increasing the piston speed will reduce the reliability and increase the likelihood of major engine failure. Therefore engines with a shorter stroke will naturally be more suitable for high-revving applications.

Parts availability: Choosing a more obscure engine capacity may lead to issues with parts availability.

Parts reliability: Some of the engine capacities shown use stronger components as standard. For example, the 4.0-litre 38A engine has larger crank journals and main bearings. This makes it inherently stronger than the equivalent 3.9-litre 30A engine.

Engine Block Identification

Engine blocks have the engine number stamped on the outside edge of the block deck, and this can be seen with the cylinder heads still in place, adjacent to the dipstick tube (see opposite page, top).

The various factory engine numbers are shown in a table in the appendix at the back of this book. This table shows the main factory engine numbers, but aftermarket engines may have different numbers stamped into the block. As an example, many of the earlier Rover V8 engines fitted to TVRs have engine numbers starting with NCK, standing for ‘North Coventry Kawasaki’ (see opposite page, middle). Other aftermarket engine numbers include JE or V8D, standing for ‘John Eales’ or ‘V8 Developments’ respectively.

There are also a number of key visual differences between the various Rover V8 engine blocks that have been produced. Here we will put them into two main categories, differentiated according to their bore diameter: 3.5in, or 88.9mm, small-bore engine blocks, and 3.702in, or 94mm, big-bore engine blocks.

3.5in or 88.9mm Small-Bore Engine Blocks

The first engine blocks, as fitted to Rovers and early Range Rovers from 1967 to 1980, utilize 3.5in-diameter cylinder bores and fourteen-bolt cylinder heads. The two-bolt main caps that retain the crankshaft are located via block registers on either side; these registers are 0.200in tall, and the ends of the main cap are 0.250in tall. On these early engine blocks the main cap to register contact area is only 0.090in tall. This is due to the design of the main caps on these early engine blocks.

Another key visual difference with these early Rover V8 blocks are the three valley ribs, which are thin compared to the ribs on later engine blocks.

In 1980 the later ‘stiff block’ was introduced, the key visual difference being the thicker valley ribs (approximately 14–15mm) common to all Rover V8 engine blocks from this point forwards. This later block with the 3.5in bore also uses different two-bolt main caps that have taller ends (0.650in), with a slightly increased main cap to register contact area (0.105in tall).

OEM 4.6 P38A engine number.

TVR 420 SEAC engine number – North Coventry Kawasaki.

Later Rover V8 block, showing thicker valley ribs.

In 1995 a version of the 3.5in small-bore engine block was produced for the military; these particular engine blocks are often referred to as ‘service’ engine blocks. These blocks were based on the big-bore 38A engine-block castings, but used cylinder liners and the crankshaft from the 3.5in small-bore engine. These engine blocks are only compatible with the later ten-bolt cylinder heads, and use the later 38A main caps but without the cross-bolts, effectively using only two bolts with the four-bolt main caps. These ‘service’ blocks can be easily modified by drilling out the castings to produce a cross-bolted 3.5-litre engine.

Although rarely seen in the UK, it is worth briefly mentioning the other 3.5in small-bore engine block that was produced, for the 4.4-litre Leyland P76 engine. Produced in Australia from 1973 to 1980, this engine block has larger main bearings (2.55in in diameter) and a taller block (0.540in taller than the standard 3.5 Rover V8). These engine blocks only use ten-bolt fixings for the cylinder heads.

3.702in or 94mm Big-Bore Engine Blocks

The first of the ‘big-bore’ engines was produced in 1989 and utilized 3.702in diameter cylinder bores and fourteen-bolt cylinder heads. These engines still retained the two-bolt main cap design from the ‘stiff block’ 3.5in bore engines, primarily used for the 3.9-litre engines fitted into the Range Rover Classic, but also used with a different crankshaft and pistons to make the 4.2-litre engine fitted into the Range Rover Classic LSE.

In early 1994, the ‘interim’ engine was introduced, using the same block casting as the later 38A engine. The earliest of these ‘interim’ engine blocks used the same two-bolt main caps as the first of the ‘big-bore’ engines, as well as being drilled and tapped for fourteen-bolt heads (although still fitted with ten-bolt heads). However, most of these ‘interim’ engine blocks used the later 38A main caps, but without the cross-bolts, just like the ‘service’ 3.5-litre engines. This means that these engine blocks can be easily modified to produce a cross-bolted 3.9- or 4.2-litre engine. They are also usually drilled and tapped for the later ten-bolt cylinder heads from mid-1994 onwards.

The ‘interim’ engines use a ‘short-nose’ (70mm long) crankshaft, as per all early Rover V8s, but have a longer key-way machined into the crank nose to accommodate a 60mm long Woodruff key. This is to drive the crank-driven oil pump, a key feature of all big-bore Rover V8 engines from this point forwards. Another key feature of this ‘interim’ engine is the use of a camshaft thrust plate, which can be bolted to the block via two tapped holes and prevents any axial movement of the camshaft.

Interim crankshaft nose, with longer keyway.

Threaded camshaft location plate holes on interim engine block.

In late 1994 the 38A block was introduced and used for the 4.0- and 4.6-litre engines fitted into the Range Rover P38A. These engines use a ‘long-nose’ (90mm long) crankshaft to drive a crank-driven oil pump and four-bolt (cross-bolted) main caps as standard. The 38A crankshafts also have larger main bearings (2.5in diameter) and larger big ends (2.185in diameter). These 38A engine blocks are all drilled/ tapped for the later ten-bolt cylinder heads, and use stretch-bolts with composite head gaskets as standard. This type of engine is also fitted with a camshaft thrust-plate as standard, and has the provision for two knock sensors on the outside of the block.

The 38A engine block technically represents the best Rover V8 production short engine ever made.

38A engine block and crankshaft.

Location of knock sensor bosses on P38A engine.

Potential Problems and Solutions

One well-known issue with the 38A engine block in particular is liner slippage. Aluminium and steel have different rates of thermal expansion, so any over-heating issues can potentially lead to a slipped liner. The Range Rover P38A and Discovery 2 had revised cooling systems that ran at higher operating temperatures for emissions purposes, but unfortunately this led to a significantly increased number of engine failures due to slipped liners or block cracking.

There are two ways of preventing the slipped liner problem occurring on any Rover V8 engine: the first is to ensure that your cooling system is in perfect working order, with no coolant leaks, and the second is to fit top-hat flange liners.

Top-hat flange liner.

A number of different companies offer this service, including ACR and Turner Engineering. These top-hat flange liners are a good ‘insurance policy’ in case your Rover V8 engine over-heats, but they are not a substitute for ensuring that the cooling system is in good condition. Although they will ensure that the cylinder liners are not able to slip, overheating can still cause other major issues such as warped cylinder heads, warped block, cracked block.

With a P38a cooling system, another approach is to reduce the operating temperature by retrofitting a lower temperature thermostat.

Block cracking behind the liner is another well known issue with the 38A engine block, although some of the earlier 3.9- and 4.2-litre engines also had this problem. The early 3.5-litre engines did not have this issue, as the smaller 88.9mm bore has more material around the outside of the cylinder liner. Although there is always a certain amount of core shift with cast aluminium engine blocks, there is always plenty of material left around the cylinder liner on a 3.5-litre engine. The nominal diameter of 93.25mm (without the liner) leaves a minimum of 5.5mm wall thickness in the surrounding aluminium.

With larger 94mm-bore engines, the nominal diameter of 98.6mm (without the liner) leaves about 3mm wall thickness in the aluminium around the cylinder liner and the waterways that pass between the different cylinder bores. With some core shift during the casting process, this wall thickness can be reduced to the point where the aluminium surrounding the cylinder liners is quite thin. If the engine then gets a little too hot, or goes through a number of extreme heat cycles, the aluminium behind the liner can crack, allowing the liner to move. Coolant can then leak from around the liner into the cylinder, and the cylinder pressure can pressurize the cooling system. This is often noticed as a slight coolant loss that gets progressively worse.

From 1993 onwards Land Rover ultrasonically tested this wall thickness on all their engine blocks, and wrote the minimum wall thickness in the valley of the engine block. So, for example, if you see ‘2.5’ written in the valley of your 3.9-litre engine block, it means that the minimum wall thickness on that engine is 2.5mm. Further to this, from 1997 Land Rover marked the 38A engine blocks (again, in the valley) with a colour instead – blue, yellow or red.

Any engine blocks that had less than the 2.2mm minimum requirement were scrapped at the factory.

Table 3: 38A engine-block colour codes

ColourWall thickness range (mm)NotesBlue2.2–2.5Used for 4.0-litre enginesYellow2.5–2.8Used for both 4.0- and 4.6-litre enginesRed2.8–3.0Used for 4.6-litre enginesAlternative/ Aftermarket Engine Blocks

Apart from Land Rover or Rover, there have been a number of aftermarket suppliers of alternative Rover V8 engine blocks. Top-hat linered engine blocks have become very commonplace over the last ten years, due to the liner slippage issues with the 38A engine. TVR produced the 5-litre Rover V8, using a longer stroke crankshaft, fitted to the TVR Griffith 500 and later to the TVR Chimaera 500: these engine blocks have been modified specifically to accommodate the increased crankshaft stroke. Throughout the 1990s, Wildcat Engineering also produced a wide range of different engine capacities – even a 6-litre version using a modified Ford V8 crankshaft with a 101.6mm bore and 92mm stroke! This engine block had no waterways between the cylinders to allow for the larger bore diameter, and used six head studs per cylinder.

Camshaft Bearings

When rebuilding a short engine we always recommend replacing the camshaft bearings. These are located in the centre of the block, and are replaced using a specific tool. If required, this tool can be easily made by your local machine shop.

Camshaft bearing replacement tool.

Camshaft bearings.

Worn camshaft bearings lead to low oil pressure and eventually loss of oil pressure, so these should be replaced during every engine rebuild.

Dimensions of camshaft replacement tool.

Core Plugs and Oil Gallery Plugs

If you are stripping and rebuilding your short engine, it is well worth removing the coolant core plugs and oil-gallery plugs prior to cleaning the engine block. This allows the coolant and oil passageways to be thoroughly flushed and cleaned prior to reassembly. The coolant core plugs are readily available and should be replaced. The threaded oil-gallery plugs can be reused.

Core plugs and oil gallery plugs.

PISTONS AND PISTON RINGS

The Rover V8 is fitted with cast aluminium pistons as standard, most of which were made for Rover by Hepolite. The later specification hypereutectic cast aluminium pistons (as found in the 38A-specification engine) are more durable than the earlier cast aluminium pistons, due to the higher silicon content.

In terms of piston and cylinder-bore wear with most road-going applications, the Rover V8 is usually very durable and long lasting. As with any engine, regular oil and filter changes will help prolong the life of the engine. If you need to retain very good piston-to-bore sealing with your road-going Rover V8, we would recommend a rebore with new pistons and rings every 50,000 to 75,000 miles (80,500 to 120,700km). It is worth noting, however, that the Rover V8 is capable of covering significantly higher mileage without any noticeable problems with the short engine. Significant factors that have an impact on engine longevity include:

•service regularity: a regularly serviced engine will always last longer

•engine loads: heavy loads, including towing and off-road, reduce the life of the engine

•engine speeds: lots of high rpm use reduces the life of the engine

•engine temperature: a cold engine will wear more quickly, so an engine that spends a higher proportion of its time at full operating temperature will last longer. Conversely, an excessively hot operating temperature, or over-heating, will reduce the life of an engine

If your engine has excessive piston-to-bore clearance you may be able to hear ‘piston slap’, the dull slapping sound of the piston skirt making contact with the cylinder bore.

Early cast pistons should be considered to have a maximum safe engine speed limit of approximately 6,000rpm, with the later hypereutectic cast pistons okay for use up to 6,500rpm. Note that these engine speed limits do depend on how long the engine spends at those particular speeds. For example, an earlier piston will last longer if only taken to 6,000rpm in short bursts, compared to a later hypereutectic piston held above 6,000rpm for sustained and repeated periods of time. If cast pistons are to be used for racing applications, they will have a significantly shorter life than road-going applications.

Forged pistons are a great upgrade for race-specification engines that consistently see engine speeds above 6,000rpm, as well as for supercharged or turbocharged engines. These are available from a number of different suppliers, with larger diameter 96mm pistons readily available for the 4.6-litre 38A-specification engine, giving an increased capacity of 4.8 litres. Custom-forged pistons are also available from a number of different suppliers, including Ross Racing, Diamond, and so on.

96mm forged pistons.

A standard piston on a freshly rebuilt engine will have a piston-to-bore clearance between 0.001in and 0.002in, but forged pistons usually require more clearance to allow for their higher rate of thermal expansion. Forced induction applications also usually require increased piston-to-bore clearances due to the higher combustion temperatures present at the piston.

If your engine is going to have a lot of valve lift, you also need to try and establish whether or not you will require valve reliefs or cutouts in the top of your pistons, to allow sufficient piston-to-valve clearance on both the intake and exhaust valves.

The location of the gudgeon pin in the piston is another consideration, particularly with custom engine builds. There are two main dimensions to take into account – the pin height and pin offset. The 4.0-litre and 4.6-litre 38A engine uses a 0.6mm gudgeon pin offset to reduce the side loads on the piston and therefore reduce the stress/wear on the entire rotating assembly. Earlier Rover V8 engines have zero pin offset.

Key features of a piston.

The pin height is also known as the compression height, and it varies between the different engine capacities.

The piston-dish volumes shown in Table 4 are for the standard quoted compression ratio of 9.35:1, unless otherwise stated.

Table 4: Standard piston dimensions

Engine capacity Compression height Piston-dish volume examples 3.5-litre 46.8mm8.5cc for 9.6:1CR,

11.2cc for 9.35:1,

15.3cc for 8.13:1

3.9-litre 49.5mm 22.5cc 4.0-litre 38A 35.9mm 13.2cc 4.2-litre 45mm 22.5cc for 8.94:1 4.6-litre 38A 35.9mm 22.3ccThe piston-dish volume also varies between the different engine capacities. Interestingly, this can sometimes be used to our advantage. For example, a 4.6-litre engine fitted with 4-litre pistons will have a fairly significant compression ratio increase. So when using non-standard components, or when mixing and matching components, it is important to check that the piston dimensions are correct for your combination of block height, rod length, stroke, and desired compression ratio.

Each piston has two compression rings and an oil-control ring. Naturally the different piston rings not only vary in diameter but also in thickness. A range of different compression and oil-control ring thicknesses were used in standard engines, as well as in aftermarket engine builds.

CONNECTING RODS

The length and type of connecting rod fitted to your engine depends on the original or current engine capacity.

Table 5: Standard con-rod dimensions

Standard con-rods are rarely a limitation on the Rover V8, and are quite durable enough for most applications, even at higher engine speeds. Naturally, the con-rods fitted to the longer stroke engines – for example the TVR-spec 5-litre – will undergo more dynamic load than the con-rods fitted to shorter stroke engines. Even so, the conrods are usually not an issue with engine speeds below 6,800rpm on naturally aspirated applications.

If you are building a very high specification engine with forced induction, high engine speeds or an alternative stroke, you may require aftermarket conrods. Due to parts commonality with some American V8 engines, forged I-beam and H-beam con-rods are readily available for the Rover V8 engine from a wide range of suppliers.

Rod ratio is the length of the connecting rod divided by the stroke. This relationship affects the behaviour of the engine: the higher rod ratio will have fewer side loadings on the piston, and will therefore be subjected to less friction between the piston skirts and cylinder walls. The higher rod ratio will also slightly increase the amount of time the piston spends at TDC (the piston dwell time), which also increases power at mid to high engine speeds.

The disadvantage with the higher rod ratios is that the intake vacuum is reduced slightly at lower engine speeds, which affects torque and engine response. Other potential disadvantages of higher rod ratio is that the gudgeon pin will need to be located higher in the piston, closer to the piston crown, and might entail the use of a shorter piston, which can lead to piston stability issues if you go too far (only really relevant with custom pistons). The maximum rod ratio is limited by the height of the block deck.

When working out the fundamental engine speed capability of a particular short engine, the mean average piston speed is another useful factor to consider. In isolation, the mean piston speed is fairly meaningless, but is more relevant when comparing different engine specifications and their engine speed capability. For example, the rpm limit of a particular 5-litre Rover V8 short engine is 6,000rpm, at which point the piston has a mean average speed of 18 metres per second. In theory this means that if a 4-litre short engine is built with the same component materials, it will be capable of reaching a heady 7,593rpm before it reaches the same 18 m/s mean piston speed!

So the 38A 4-litre engine has the highest rod ratio with standard components, as well as the joint lowest piston speed. Therefore it is safe to assume that this particular short engine derivative has the highest engine speed capability out of all the standard Rover V8 short engines.

Table 6: Rod ratios and mean piston speeds

Rod ratio Mean piston speed @ 6,000rpm (m/s) 3.5-litre 2.02 14.2 3.9-litre 2.02 14.2 4.0-litre 38A 2.18 14.2 4.2-litre 1.87 15.4 4.6-litre 38A 1.83 16.4 5.0-litre TVR-spec 1.55 18CYLINDER HEAD BOLTS

There are two standard types of head bolt fitted to the Rover V8, as well as some aftermarket options. Up to 1993, Rover V8 engines were fitted with head bolts that are technically reusable, although if doing so, it is always worth checking them for overall length, inspecting the threads for damage, and checking that the thread pitch is still correct. From 1994 onwards, engines were fitted with stretch-type bolts instead; these are not reusable and should be replaced every time they are removed after use.

ARP cylinder head stud versus standard head bolt.

ARP head stud kits are also available for the Rover V8, and these are superior both in terms of clamping force and due to the fact that you can thread the studs into the block before fitting the heads. They are also reusable, but they are not without potential issues. If there are any issues with the threads in the engine block, then you will encounter them sooner with the ARP studs. There are also some ARP stud kits that are sold as being suitable for the Rover V8, but are not entirely correct. The thread lengths are not correct, so it is important to check that the thread lengths on the studs match the threads in the engine block. They should not bottom out, but they do want to utilize most of the thread available in the block. ARP studs should be fitted by hand using an Allen key. Do not over-tighten!

CRANKSHAFT

Rover V8 crankshafts are usually very strong and without issues, unless they are being run at very high engine speeds or with large amounts of boost in forced induction applications. The slight exception here is with the TVR-spec 5-litre Rover V8 crankshaft, with its long 90mm stroke. These crankshafts do occasionally suffer breakages when revved much beyond 6,000rpm, so if you have a TVR-spec 5-litre it is well worth limiting the engine speed to a maximum of 6,000rpm.

Stronger EN24 billet steel crankshafts are available, which are capable of operating at higher engine speeds and with more boost in forced induction applications. Crankshafts are also available with a range of alternative stroke lengths, including an 86.26mm stroke for short-stroke 5-litre engines, and a 92mm stroke for 5.2-litre engines. As previously mentioned, it is particularly important to work out the maximum allowable engine speed with the longer stroke crankshafts.

A number of other features should be considered when purchasing a crankshaft for your engine. One is the keyway in the front of the crankshaft, and another is the length of the front of the crankshaft (called the nose). Earlier pre-Serpentine Rover V8 engines are fitted with a short-nose crankshaft and a short keyway. The first Serpentine engines, known as the interim type, are fitted with short-nose crankshafts, but with a long keyway. This longer keyway is to run the crank-driven oil pump, fitted to all Serpentine engines. The later 38A Serpentine engines use long-nose crankshafts with a long keyway.

Pre-Serpentine crankshaft – short nose and short keyway.

Serpentine interim crankshaft – short nose and long keyway.

The other features to consider are the main bearing and big-end bearing diameters, with the 38A block having larger main bearings (2.5in diameter) and larger big ends (2.185in diameter), for example. It is also worth noting that the 38A crankshafts will not fit the earlier engine blocks without the blocks being modified for clearance – this is due to the larger counterweights on the 38A crankshaft.

If there is any scoring or wear present on the crankshaft bearing faces, these faces need to be reground and fitted with different size bearings to suit. If using a second-hand crankshaft for an engine build, it is important to check the diameters of the various crankshaft bearing faces to see whether they have been reground before, and to ensure that the correct size bearings are fitted.

Serpentine 38A crankshaft – long nose and long keyway.

CRANK PULLEY ASSEMBLY

A wide variety of crank pulley assemblies have been fitted as standard to Rover V8 engines over the years.

All pre-Serpentine engines have pulleys that accommodate a traditional V-type belt. These engines also usually use more than one V-type pulley on the crank when running additional ancillaries such as power steering and air conditioning. The crank pulleys are bolted to a vibration damper via three or six 5⁄16 UNF bolts. There is also often a balancing rim located at the rear of the crank pulley assembly, which is used to balance dynamically the entire crank pulley assembly. The vibration damper has a keyway that locates on to the crankshaft key, and is bolted to the crankshaft via a large 3⁄4 UNF bolt with a 15⁄16in (23.8mm) hex head. This bolt is technically reusable, but must be inspected before reuse for signs of stretching. It is also worth applying a drop of thread-lock during assembly. Some early Rover V8s fitted to Land Rovers used a crank pulley bolt that had a ‘starting dog’ as part of the bolt head instead, so that the engine could be cranked over with a starting handle.

Interim-type Serpentine engines have a similar type of vibration damper, but with a seven-groove serpentine pulley (to suit a 7PK serpentine auxiliary belt). On both pre-Serpentine and the interim-type Serpentine engines, the vibration damper has the timing marks located on the outside edge. It is possible for the outer section to separate and rotate around the inner damper section, so that the timing marks are no longer correct. For this reason it is always important to verify that the TDC marking on the damper correlates with when piston no. 1 is at TDC. Once this has been checked, it is then worth marking the damper across both the inner and outer sections so that if they do separate and rotate it will be easily spotted.

Crank pulley bolt with ‘starting dog’ for starting handle.

The 38A Serpentine engines are fitted with a vibration damper that has the serpentine pulley grooves machined into the outer section, effectively forming a one-piece crank pulley assembly.

38A front crank pulley.

FLYWHEEL

We will not go into too much detail here – also, many Rover V8 applications are fitted with an automatic gearbox, so this section is not applicable in those cases.

With regard to flywheels on Rover V8 engines, the only thing worth mentioning is that most standard OEM flywheels are primarily suited to heavier vehicles, such as Land Rovers. For this reason, lighter-weight vehicles fitted with Rover V8 engines will usually benefit from having a lighter-weight flywheel, although it is possible to go too far and reduce the drivability of the car. A lighter-weight flywheel will allow the engine