Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

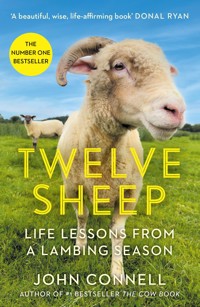

For John Connell, the lambing season on his County Longford farm begins in the autumn. In the sheep shed, he surveys the dozen females in his care and contemplates the work ahead as the season slowly turns to winter, then spring. The twelve sheep have come into his life at just the right moment. After years of hard work, John felt a deep tiredness creeping up on him, a sadness that he couldn't shrug off. Having always sought spiritual guidance, he comes to realise that, in addition to the soothing words of literature and philosophy, perhaps the way ahead involves this simple flock of sheep. In the hard work of livestock rearing, in the long nights in the shed helping the sheep to lamb, he can reflect on what life truly means. Like the flock that he shepherds, this book is both simple and profound, a meditation on the rituals of farming life and a primer on the lessons that nature can teach us. As spring returns and the sheep and their lambs are released into the fields, skipping with joy, John recalls the words of Henry David Thoreau, reminding us to 'live in each season as it passes.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 174

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise forThe Cow Book:

‘This book is a vivid and sharply observed account of a way of life which is almost invisible, a new hidden Ireland. It is also a fascinating portrait of a single sensibility, a born noticer, someone on whom nothing is lost, observing birth and death, the landscape and his own heritage’ Colm Tóibín

‘I usually view rural Ireland from a train or carwindow but reading this gripping, fascinating book I feltI was becoming a cattle farmer’ Roddy Doyle

‘A gorgeous read, full of warmth, truth and tentative wonder. John Connell has written ‘an elegy to the nature I know’, but this book is an elegy to so much more – to art and myth and sorrow and longing’ Sara Baume

‘A brooding, powerful memoir about a 29-year-oldman’s return to the family farm in Ireland’ Guardian

‘A gorgeous evocation of farm life’s recurring cycle of births, deaths, seasons, weather, chores and life lessons, all spun into a lovely web of stories illuminated by crystalline prose. What comes through on every page is Mr. Connell’s heart and humility – and his profound appreciation for the animals who depend on him for their well-being, and vice versa’ Wall Street Journal

Also by John Connell:

The Stream of EverythingThe Running BookThe Farmer’s SonThe Cow Book

First published in Great Britain in hardback in 2024 by

Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2025 by

Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © John Connell, 2024

The moral right of John Connell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Photograph on p. 81 © John Connell Image on p. 143: Anguish (Angoisses) (1879), August Friedrich Albrecht Schenck, engraving, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased, 1880. Reproduced with kind permission of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Image on p. 147: Shepherd and Sheep © Erich Hartmann/Magnum Photos.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN 978 1 80546 191 3

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

1 We must take a stake in the future

2 Home is where the heart is

3 Walking is good for the soul

4 In waiting, we grow

5 We must keep wonder in our minds

6 Labour is unavoidable

7 We must love our home

8 Death is part of life

9 All mothers are a link to the great mother

10 We must keep beauty in our minds

11 Health is wealth

12 Love is what you need

Epilogue

For BrídViv and OliverThank you for the words

He tends his flock like a shepherd:He gathers the lambs in his armsand carries them close to his heart;he gently leads those that have young.

Isaiah 40:11

I long for scenes where man hath never trodA place where woman never smiled or weptThere to abide with my Creator, God,And sleep as I in childhood sweetly slept,Untroubling and untroubled where I lieThe grass below – above the vaulted sky.

John Clare – ‘I Am!’

LESSON 1

We must take a stake in the future

We try and live simply but the world is complex. It has always been this way.

It is early autumn and I am standing in the sheep shed of our farm. Before me stand twelve sheep. They are, to be precise, twelve hoggets, the name we give to maiden females. These twelve ladies are mine. I have bought them from my parents with the money I earned from my words, from my books. I am a shepherd for the first time in my life. I am in the twilight of my youth and the budding of my middle age. I am older than Christ when he died and the same age as Buddha when he attained enlightenment. Both figures have walked beside me for so many years now. They have been part of my continuance in ways I think that count for some good, though I’m no sage.

I’ve known sheep for seven years now. Seven years as a farmhand, seven years as a midwife and seven years, at times, as an undertaker. It has been a long apprenticeship. I came home to Ireland from Australia to try my hand at being a writer, but in the process, I became a farmer. It happened naturally: it began with the sheep. It has been a sojourn into the earth and its creatures, albeit one in which I have never been an owner, never before as a farmer in my own right.

I have bought the twelve animals for many reasons but perhaps the one, the most important, is that they are a stake in the future but sheep also challenge you to live in the now. I like this mission. I must be ready for both situations, and as I look at the girls in front of me, I come to think that this is the right thing for me to do. The right journey to undertake.

Sheep are earthly creatures. They eat, they live, they die: they are wholly of this world. The sheeping business is part of this journey of life. Our work with the animals provides food for the people of the cities and towns of this world; their wool, though not of much monetary value to us, provides the raw material for clothes, for warmth in these cold times.

The girls will live in our fields; they have run with our blue Texel ram and come to be in lamb. It is this journey that interests me. This journey from youth to motherhood. The coming of the lambs will drop life on me and maybe there will be a wisdom in that. A learning in that. I am a man in search of new life: it will be brought from the wombs of these creatures. In the lambs, I set my aims. They will be my goal, and their passage to this world my prize.

I have worked cattle and horses but there is something that is calling me in these sheep. In their quiet nature upon this earth. In their nibbling over grass, their gentle walks upon our soil. The sheep give me calm; they ease a busy mind with their approach to the world. The sheep wants nothing more than to be a sheep and maybe I can learn something in that simple wish.

In working with sheep as I do now, I know that there will be labour. Hard work is not something I will shy away from. There will be feeding and probing. Dipping and shearing. All of this is the way of a shepherd. It is physical, intensive work. Work that demands a strong body or a body that is willing to be put through its paces. To work with animals needs a factor of strength and perseverance. Of course there, too, will be life and death. And perhaps in some queer way, heaven and hell in the days that come.

Though the work is only now beginning, I can say that these sheep have already saved me. They have brought me back from an edge. Before the twelve, I was suffering from what I can only call a fatigue, one that was perhaps soulful as much as physical. For six months before the sheep, I was empty and worn out. I had finished a book and found myself spent. There was, I reasoned, no more to say; perhaps I had said it all already. What do writers do when the words will no longer come? I did not know. It was a new threshold, a dark threshold.

I battled a tiredness such as I had not felt in many long years, and though I slept, I could not rest. My wife called it burnout; I called it a soul tiredness. I tried to write book after book but nothing came and then the stories dwindled down to a trickle and the well, as I had known it to be before, so full and overflowing, was dry and empty. It made me sad for the first time in a long time. It was not a depression, a dog I had danced with before, but there was melancholy and it wore me out all the same. The sadness felt harder than depression, as it bred a loneliness in my body and my mind that I did not want or like. The sadness and tiredness sapped away my creativity and for a writer that was like losing a part of myself, a much needed and valued limb. I did not sleep well. I did not rest well.

I lived for a time in this vast chasm. My wife and I bought a house. I helped a friend through the deaths of his young twin daughters after a tragic accident. And I thought seriously about leaving the land, of returning to a city and becoming an urban person once again. I missed the challenge of the city: in the quietness of the countryside, in which I had heretofore found inspiration, now I found nothing. It was a hard time, my empty time.

After a period, I farmed and walked the earth and gradually slowed down my life and, in many ways, my soul too. I removed myself from unwanted social outings and began to meditate again on the nature of life. I thought of the bards of the land, from the English pastoral poet John Clare to the environmentalist Rachel Carson. I remembered Henry David Thoreau’s great line from Walden: ‘Live in each season as it passes, breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit and resign yourself to the influence of the earth.’ There was something in that notion of ‘the influence of the earth’: maybe with this soul weariness I had not been in contact with her. I wondered if my own land could be a personal Walden, if I could truly claim my natural inheritance again after it seemed to be lost. To find or discover a personal Walden is to find the source of solace in a weary world. Home can be that place, a land of prisms through which we can see better our true inheritance. When we discover our personal Walden, we refract not just light but life itself.

One day, while reading, I came across a line by John Clare which said that he found the poems he was so beloved for in the fields and wrote them down. That struck me deeply and truly. Maybe the fields were the answer I was looking for? Clare knew something of sadness and longing, of belonging and not belonging. He had been hailed once as the great peasant poet and then cast aside when fashions changed in London, and he had ended his days in an asylum.

Clare, Thoreau and Carson; they spoke to me in new ways, and though their words are now old, I found fresh insight in them. I wondered in that time, and in the wondering, questions came. Into the living sea of waking dreams, as Clare put it, I found newness. The bards of the land were all in their quiet unhurried ways teaching me. In this space, I asked myself what I was doing here. It is, I think, a question we must all work out ourselves at some point in our lives. From the company director to the builder’s labourer, we all face the question of whether we should maintain or change, if we should evolve or dissolve into something else. It was a time of great thought, a time when sadness went hand in hand with tiredness. Maybe in melancholy we can find new ways of looking at the world? I do not truly know.

After a time in the slowness, something happened. An idea came to me; the notion of the twelve sheep descended upon me. It came, as all great personal revelations do: quietly, without pomp or ceremony. It was not some Shakespearean apparition – there were no ghosts hovering over me, no Banquo moment. Rather it was an internal vision, I suppose, one where I could see myself with twelve sheep, walking upon the earth as a shepherd in the cathedral of nature. It came gently, like the blossom of the yellow winter rose had come to our garden when I was a child. It was a quiet hegemonic thought that refused to go away. Ideas, I think now, do not give, or rather are not given, their full virtue. A new idea is a thing to be treasured; it doesn’t matter if it is original or not. A personal idea is new to oneself. That is all that counts. The idea, my idea, was a simple thing: to buy the twelve sheep, to follow their lives and to learn from them; and in that idea, I was reborn. The fatigue, the soul tiredness, lifted to be replaced with a fresh sense of purpose. My existence had an aim and my incompleteness was ended. I let go of my sadness. It was a new-found freedom. As Henri Nouwen, the writer, said: ‘Most of us have an address but cannot be found there.’

I break from my story and look at these sheep, my sheep, again. These animals have been stapled to my heart, to the bulletin board of life; they have made the route home for me once more. Already, they have taken me out of myself or, rather, brought me back to myself. In the work of the sheep, I have a new way to work. I am in a new landscape, the tierra of my reunification.

Now, I fill a bucket of nuts and pour it into the small feeder in the shed and the twelve sheep come forward to eat. I rub their heads and feel their shoulders. They are twelve strong girls, twelve true addresses. One can judge a sheep by the meat upon its carcass. We grade them by looking at their straight backs and udders and make a mental picture of their features. I learned this way of seeing from my father, from our neighbours and from my studies. It is a new way of looking at an animal. A learned way that I have perfected in my apprenticeship.

Twelve is, I think, a good number, a hearty number. There are twelve months in the year and twelve signs in the zodiac (one of which is the ram); indeed, there were twelve apostles to our Lord. Hercules, when he carried out his mythical labours, completed twelve tasks. In the majesty of numbers, they seemed the right digits.

I’ve known these hoggets since birth and they know this farm. They were born here. Before the girls, there were other sheep – ones at the livestock mart, others belonging to neighbours, even some from the internet. We carried out research trips, we saw sheep aplenty, heard stories from an auctioneer in Leitrim about shearing sheep for a famous celebrity and met traders and day men, but none fit the bill. Some were skinny, some with bad teeth and broken mouths (a sign of age in sheep), while others just didn’t seem to hit the sweet spot for a buyer. There are 3.7 million sheep in Ireland spread out over 35,000 flocks. There are sheep for sale every day but none so storied as these twelve.

It was my father who suggested we keep them on after our research trips had come to nought. It was my mother who said they should stay. They are from the old ram, and in buying them from my parents, they have not been uprooted from our home nor removed from this patch of earth. If I had not bought them, they would have been broken up, dispersed to marts and sale yards. Some might not have been kept for breeding and ended up under a butcher’s knife or on a slaughterhouse floor. I did not save them from slaughter, as all things end that way at some point, but by my actions I kept them on our farm, and for that I am glad. In their genes will live on new sheep, new adventures.

They are Suffolk crosses with good breeding, their black faces revealing their ancestry back to the start of our days on this farm. We began with Suffolks and learned the ways of sheep with this breed. I like the Suffolks: they date from the 1700s, when Norfolk Horn ewes were crossed with Southdown rams in England. The first flock came to Ireland in 1891. They have never left. They are all over this island now and rightly call it home. They are suited to our lowland farms. They can grow in this landscape. They are a proud and, to my eye, a noble breed, their strength and size matched by their maternal qualities.

The girls are my best hope of learning life’s lessons, for in them are contained both my beginner’s mind and my guiding hand. The lessons, I think, will not all come at once: they will be peppered through the season in the ups and downs, in the quiet and busy moments. Perhaps I hope to learn most of all how to be alive again after my period of inaction. These sheep are the route to my ‘clay soul’ as John O’Donohue, the Irish poet and philosopher, called it. One cannot raise sheep to be wise nor train them to be brave, but in their quiet way, they are teachers. They know where the good earth lies, where the best shelter is to be found. To me, they are like little Buddhas wrapt in white fleeces, calm and serene, dropping wisdom slowly, or perhaps more fitting to this landscape, like the monks upon Skellig Mhichíl in the south of the nation long ago.

The sheep jostle and push one another now for the last of their nuts and I watch them in their different personalities. To an outsider these sheep may all seem the same, but if we take the time to look and observe them, they are as different as we are from each other. There are bullies and battlers in the group. There are girls who will dominate the others to get the best position for eating. I will get to know their personalities over this season. I hope they will be good sheep. I bow to them now for they deserve my awe. I’m no rancher, with my twelve ladies, but they are tying me anew to this land of ours. They and their bellies are full of life that holds such promise.

Behind me now, I hear my father walking up the shed. He is happy to see me take on this mission. It was not that long ago that we fought over farming and life choices but those times are past: we see each other now as individuals. I am a writer and he respects that. He is a farmer and I respect his knowledge. He is wise and calm and, looking at the sheep, he produces his old, practised phrase, adapted to this moment: ‘There’ll be twelve stories to be told before the season is done.’

In a way, I think the first lesson has come already: to grab the future and let go of the past. This book, short as it might be, will be a record of this time in the life of these sheep and this land and living of ours. A menagerie of the trials and tribulations. A story of when the earth speaks, and we listen. I have taken this stake in my future. It is my first lesson, come what may. I am ready to learn.

LESSON 2

Home is where the heart is

H