Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ylva Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

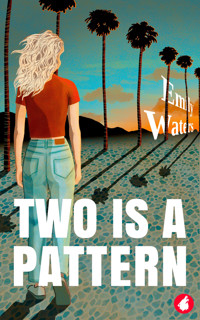

A charged lesbian romantic suspense set in the early nineties, with gripping twists, turns, and surprising secrets. A mission gone wrong leads to rising-star CIA operative Annie Weaver quitting her job and reinventing herself as a college student. But the CIA, desperate for her skills, refuses to let her go without a price. Annie finds herself juggling classes in Criminology and falling for her beautiful landlord, Professor Helen Everton, while dealing with off-the-books secret missions for an increasingly controlling ex-boss. As the perceptive Helen circles ever closer to the truth, Annie has to figure out how to keep her freedom without putting Helen in danger—and without revealing her own past.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 388

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table Of Contents

Other Books by Emily Waters

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Other Books from Ylva Publishing

About Emily Waters

Sign up for our newsletter to hear

about new and upcoming releases.

www.ylva-publishing.com

Other Books by Emily Waters

Honey in the Marrow

Acknowledgements

Thank you to everyone who helped make this book possible: Charity for being my beta and, so often, my muse. I always want to write something you’ll like. Thank you to Astrid for folding me into your cool club of Ylva writers, to Genni for editing with me, and to my partner, Jacob, for loving me unconditionally while so often I’m living in my head. And perhaps most importantly of all, thank you to my dogs, Daniel and Sophie, who sat in my lap or snoozed next to me while I wrote this book. All I ever want to do is go home and hang out with my dogs. This book is for them.

Chapter 1

Thirty-six down was an eight-letter word for rueful, remorseful, repentant. Annie picked up her pen and tapped it against the handle of her ceramic coffee mug.

“I’m not a waitress, Anabelle! You know where the coffeepot is,” her mother Patty said, her voice light and airy but her words biting.

Annie looked up from her crossword puzzle, momentarily bewildered, then shook her head.

“Sorry, Mom. No, I was just thinking.” Annie was a fidgety person by nature. Always squirming in her seat, drumming her fingers, clicking her pens restlessly until someone made her stop. Her best friend in undergrad—a tall, blonde brainiac named Lori—had once bought her as a gag gift an expensive pen designed for astronauts to take into space. It had been made to look like the American flag—red and blue anodized aluminum with little white stars—and you could write with it anywhere. Upside down or underwater or on practically any flat surface. Lori had said it was the only pen that might actually outlast a stressed-out Annie during finals.

Annie had given it to her father, Ken, who still had it on his desk in his office. It wasn’t that she hadn’t appreciated the gift or the gesture, but Annie liked her cheap little pens and not having to feel guilty about gnawing up the top of a twenty-four-cent Bic. The pen she held now was resting against her bottom lip, in place to be chewed, but she wasn’t thinking about the crossword anymore. She was watching her mother angrily scrub a muffin tin at the sink.

Her parents had been ticked with her for some time now. Ever since she announced her intention to go back to school.

It was Lori’s idea, actually. Not another degree, but the idea of going to school out West. They’d both gone to the University of Mississippi and become friends while Annie worked her way through an economics degree and Lori studied prelaw. They had no classes together their first semester, but Lori had lived three doors down from Annie’s dorm room. The next semester, they took the same Russian language class. For the next three years, they were nearly inseparable. After graduation, with their matching caps decorated to say Class of ’87, Annie was recruited to the CIA and went to Georgetown while Lori went to study law at Stanford.

They still kept in touch, though they weren’t as tight as when they were twenty. Annie had mentioned in one of her letters last year that she was thinking about pursuing a second master’s degree, maybe something more practical than Slavic languages. The government had technically paid for that one, but she’d recently resigned to figure out what she really wanted to do. Law like Lori? Foreign policy? Education? She could teach, maybe.

Lori had written back, expressing support for the idea. She mentioned that there were some great schools out West where she lived and told her not to discount it simply because her parents thought it was all stoned hippies past the Rocky Mountains. Lori probably meant Northern California because she’d settled in Marin County with her husband, Louis, but once Annie started to research, most of the schools she applied to were in the southern part of the state. She’d settled on criminology; it was a career change that would let her utilize her skillset.

Her mom finished scrubbing the muffin tin, banged it into the dish rack, and started on the big cast-iron skillet she’d used to fry bacon for breakfast.

Annie was three days away from moving cross-country, and her parents still were not entirely on board. Her father thought it a waste of time and money, and he was horrified at the amount of the loan Annie had procured. Her mother never tired of pointing out to her only daughter that by the time she was twenty-seven, she had a toddler and a baby on the way, and what would Annie have to show for herself except for a pile of degrees and no job?

“Mom, leave that big heavy pan. I’ll do it,” Annie offered.

“What about next week when you aren’t here anymore?” Patty asked. “Who’ll do it then, hmm? Me, that’s who. So I may as well get used to it.”

Annie sighed, picked up her pen, and returned to her puzzle.

Thirty-six down.

Rueful, remorseful, repentant.

Her pen scratched against the newsprint.

Contrite.

* * *

Three debate trophies in high school and negotiation training by the United States government and it still took Annie most of the summer to convince her father that she didn’t need anyone to drive from Ohio to California with her. At first, both of her parents had insisted on going, and then she’d got it down to just her father.

Two nights before she was due to depart, she got her wish. Her father relented if she promised to stop in Missouri and again in New Mexico to sleep solid nights in hotel beds. He even offered to pay for the hotel rooms, then spent the rest of the evening calling around for the best rates and booking her rooms, reading his credit card numbers over the phone loudly.

Annie hovered in the hallway, fretting.

“He just loves you is all,” her mom said, coming up behind her.

“I know. But it’s too much money.”

“Can’t put a price on your safety, honey. It’ll make him feel better, so you may as well let him do it.”

Annie nodded; the weight of his care heavy enough that it felt difficult to move from the spot.

She’d been feeling guilty about a lot of things lately. Going back to school, moving far away from her parents when she’d just come back to Toledo. Quitting her job with the CIA. Turning down a job offer from the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington DC six months ago even though she had no other prospects. It wasn’t the idea of being a police officer she disliked; it was the way Deputy Chief Mason Worth had offered her the job. Worth was a celebrated and decorated officer, but the way he praised her—offering her a better-paying job and an alluring life in a new town—made the hair on the back of her neck stand up. He was so desperate to poach from the intelligence community that he contacted her the day after she left the Company. She had no idea how he knew anything about her, and the nicer he was to her, the more her stomach churned and the worse the fight-or-flight feeling got. So she said no and flew home to regroup.

Anabelle Weaver didn’t need another authority figure in her life. She’d already learned that lesson the hard way.

She didn’t sleep well the night before she was supposed to leave for California. Part of it was her childhood mattress, narrow and squeaky. But it was also her jangly nerves about her sense of direction. The majority of the trip was driving west on Interstate 40, but first she had to find her way out of the city, then negotiate the freeway system once she reached Los Angeles’s outskirts.

Annie had thought seriously about going to UC Berkeley, had even tentatively filled out the form to accept, but at the last minute, she’d mailed the one to UCLA instead. Berkeley had more accolades, but UCLA’s program allowed her to earn a master’s through the law school without having to become a lawyer. The more temperate climate of Los Angeles was a factor as well, as was the anonymity of a sprawling city like Los Angeles. It was a shame that Lori wouldn’t be closer, but, realistically, they’d have little time to spend together anyhow, not like they once had. No movie marathons, no nights at the bar. Lori had a family, and Annie, having one master’s degree under her belt already, knew exactly how much work was in store for her.

Too nervous to sleep, she rose an hour before her alarm, well before anyone else in the house stirred. She took a quick hot shower, then carefully braided her hair so it would be manageable during the day. Her natural hair was strawberry blonde—not quite red. She had bleached it for her job in an effort to dim her most memorable feature—not the worst thing she’d ever done for the Company—and right now, she had about three inches of strawberry roots. She was happy to see her true color coming through again.

She studied herself in the mirror. Her braid stretched the skin of her forehead back. Her face was shiny, and she looked tired. For the longest time, she had looked school-age, ambiguously so. If she wore something that pushed her tits up high, she was often mistaken for a coed or a high schooler or the harried grad student she once was. But now time was catching up. She rubbed lotion into the skin around her eyes and onto the dry patch on her forehead.

Walking back to her room, her towel wrapped tightly around her, Annie saw light filtering up the stairs and heard the chug of the coffee maker coming alive. Her parents never bought new things just because they could; they always waited for things to die first. The coffee maker was big, old, and slow, but it still made coffee, so it stayed.

She dressed in jeans, pulled a pair of socks up to her knees. She wore her soft, gray bra, the one that wouldn’t dig into her shoulders and poke her in the ribs with the bent, out-of-shape underwire. A long-sleeved white shirt and her sweatshirt over that. She’d be too hot later when the sun came up, but right now she was worried more about comfort. She could always pull over and dig out a T-shirt later.

Her mom was in the kitchen, a pink, quilted robe over her white nightgown. Her hair, mostly white now, stuck up everywhere except at the back of her head, where it had rested all night against her pillow. Her mother greeted her with a smile. It was maybe too early for her to remember that she was sad and hurt and out of sorts.

“Pretty girl,” her mother said. “Do you want some coffee?”

She accepted a small cup and sipped it slowly. She wanted to down the whole pot but didn’t want to have to stop thirty minutes into her trip to find a bathroom to pee in, or worse.

A little while later, her dad got up. They’d mostly packed the car the night before, filling the trunk and back seat with boxes of clothes, shoes, and books. In the passenger seat was a laundry basket filled with toiletries, towels, and other odds and ends. She’d sold most of the stuff in her apartment when she’d moved back to Ohio, so other than clothes and books, odds and ends were all she had left. And her car, of course, which was by far the nicest thing she owned.

Now her dad loaded the rest, tucking things in wherever there was space. Her mother offered to fix her breakfast, but she waved it away, too nervous to eat.

She didn’t want to drag out the goodbyes. She didn’t feel ready to leave, but she knew she needed to go and it was time to rip the Band-Aid off, get on the road, and put some miles in before the day got away from her.

There were long hugs and tears, of course. Her dad slipped her two hundred-dollar bills while her mom was busy wiping her eyes. Then her mom slipped her a crisp fifty while her dad was double-checking that the trunk was closed up tight.

Just before she got into the car, her dad handed her the map and handwritten directions he had prepared for her, the addresses and phone numbers of the scheduled motels written in his slanted scrawl. He’d used the astronaut pen. Annie recognized the ink.

Her throat felt thick as she drove away, watching them get smaller in the rearview mirror.

But she didn’t cry. Annie was an expert at leaving.

* * *

She stopped the first night in Kansas City after driving nearly eleven hours. It was just a Motel 6, but the lobby was clean, and she was weary and rumpled and starving half to death. The man behind the desk barely looked at her, uninterested in a woman traveling alone.

He gave her the key, pointed at the glass door to the lobby, and said, “Go to the left and park over by the fence. You’re on the second floor.”

She thanked him, returned to her car, and parked where he had indicated.

After checking that the car was locked and nothing valuable showed through the windows, she lugged her suitcase up the stairs and into her room. Then she stepped out to use the pay phone at the end of the walkway.

Her mother picked up after one ring. “Anabelle?” she asked anxiously.

“Yes, it’s me,” Annie said, equal parts exasperated and grateful. It was quite a burden, all the love her family heaped on her. She didn’t always feel like she deserved it, and carrying the weight was sometimes a struggle. “I made it to Kansas City.”

They chitchatted briefly as her dad yelled from another room and her mother repeated what Annie had said. She spent another minute and a half trying to extricate herself from the call, promising to rest tonight and drive safely tomorrow, reassuring them that the car hadn’t made any funny sounds. Annie had been making good money when she bought the car new a few years back, and she had been out of the country as much as she’d been in it, so the car mostly had sat in her garage. This trip would be the most miles she’d put on it yet.

She hung up and listened as her coin clinked down to the bottom of the pay phone. She froze when she heard footsteps shuffle on the ground below. She moved quietly to the railing and looked down but couldn’t see anything. Had someone been listening to her? Not much to hear, really, but it was hard to shake the prickly feeling along the back of her neck.

Then she saw the glow of a cigarette as it arced out and landed on the parking lot blacktop. She heard steps and the sound of a door opening and closing below.

Paranoid, that’s what she was. There was no longer any reason to look around corners, to double back to make sure no one was following her, but she found herself doing it all the time. Even here in the States, where she was just another fair-haired and corn-fed American. Nothing special anymore.

That was the way that she wanted it, why she’d left.

She returned to her room and pulled on her hooded sweatshirt. Picked up the canvas shoulder bag that she used for a purse and slung the strap over her head. She had to find dinner, and if her car weren’t full of crap and low on gas, she’d drive somewhere. Instead, she walked across the dark parking lot toward the nearest fast-food joint with her hood up and the sleeves of her sweatshirt pulled down to her fingertips.

She bought a sack of greasy fries, a cheeseburger, and a bright blue slushy drink that was so sweet it made her teeth hurt and her blood sing. Sugar could right any manner of wrongs. She walked back to her room with the smell of fries driving her slowly insane, then ate every scrap of food in the bag before falling asleep with the TV on.

She woke up after midnight and stumbled into the bathroom. After she washed her hands and face, she looked in the mirror and saw that the slushy had stained her entire mouth blue.

* * *

The next night, Annie spent in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and then it was a straight shot through the Southwest until she picked up Interstate 15 in California.

She honked her horn as she crossed the state line from Arizona, but alone in the car, the gesture made her life seem small. She had listened to the same five cassette tapes on the entire drive, and as she approached civilization, she was happy to switch back to the radio. Even staticky commercials were a refreshing change.

She’d had second thoughts from the moment she left Toledo. Was this the right thing to do? More school and going into debt? No one but her would be paying for this degree, and she wasn’t even sure what she wanted to do besides help people in a less shadowy way. Wasn’t that what academically inclined people did in times of doubt—fall back on more education to buy time?

She liked to have a plan, to have all the answers before she started something, and this was not that. Still, maybe venturing into the unknown would be good for her. She could go to classes, learn something, figure it out as she went. But it was nerve-racking too. She didn’t even have a goal past getting the master’s.

She’d overslept that last morning, which meant a delayed start, and she stopped at a gas station somewhere in West Covina to call the residential office to say she’d be arriving later than expected.

She got turned around once she entered the city and had to pull over to study a map. She finally found the campus by dumb luck, then asked someone walking along the sidewalk for directions to the building.

The plan was to live on campus in a tiny graduate student apartment, but when she got to the residential office, an undergrad working the late shift looked up from his book and passed her a voucher with a shrug. She looked at it. At the bottom was a line for when the voucher expired. Someone had written in “8/31/92,” which was exactly a week away.

“Stuff fills up fast,” the student said. “The university puts up overflow students in a motel for a week while they make other arrangements.”

“Other arrangements,” she echoed, too exhausted to be mad. “What does that mean exactly?”

“Come back tomorrow,” he said. “My boss will be here from eight to five, and he can explain.”

“And where is this motel?” she asked, flapping the voucher at him.

“Oh, it’s like three blocks from here, I think,” he said with another shrug. “Like…north?”

“Write down the address. Written directions, please.”

He closed his book with a sigh, pushed back from the desk, and stood up. “Let me ask.”

It turned out that the motel was close, though she drove past it the first time. Someone honked at her, maybe because she was going too slow, maybe because she still had Virginia license plates. Maybe Californians liked to honk. She flipped on her turn signal when she saw the motel sign again, parked outside the lobby doors, and shut off the engine. She allowed herself a few moments to collect her thoughts and assess. There was no point in being mad at the situation. The kid at the desk didn’t seem to know much at all. She would get everything sorted out in the morning.

Anyway, what was one more night in a motel after two thousand miles?

* * *

Annie made the man explain it three times. What it came down to was this: they always overbooked graduate dorms because there were usually a few students who dropped out at the last minute. Financially, it made more sense to overbook than to have empty rooms. But this year, no one had dropped out, and since Annie had waited so long before accepting her slot at UCLA, she was at the bottom of the barrel.

“We give you a week to make other plans,” the man said.

“Other plans?” she screeched. “I had plans! You’re the one who made them fall through!”

“I understand our system can be complicated—”

“You think it’s my failure to comprehend your system?” She made air quotes. “You think that’s the problem here?”

“Ma’am—”

“Look, I have been in California for about twenty minutes, and I’m really not equipped to go house hunting on my own. So either you find me the school housing that was promised to me, or you produce a better option.”

He pushed his glasses up to rub the bridge of his nose. His plastic name tag said Paul.

“I can’t help with outside apartment rentals, but I can give you a list,” he said finally. “We usually only give it out to postdoctoral and foreign exchange students, but because of this unique circumstance, it might be a good solution for you.”

“What list?” she asked.

“It’s a list of faculty who are willing to take in students. Rent out rooms in their houses for a quarter or two. It’s meant to be short-term, but it should be enough to get you into student housing later.”

Annie held out her hand. “Give me the list.”

* * *

She shoved the list of names into her bag and made her way to the registrar building to sign up for classes. That involved several hours in line. By the time she’d finished, she needed lunch. Then she went to buy books. It wasn’t until she got back to the motel and moved the most valuable things out of her car that she even remembered the list.

She called her parents, knowing they’d be out, and left a cheerful but vague message, promising to call again when she was more settled. She’d lie to them if she had to, but she’d rather put off telling them anything for as long as possible. She certainly wasn’t going to tell them about this motel, about the overflow situation in student housing, or about how she’d spent all that cash they’d slipped her on textbooks in one fell swoop. And she wasn’t going to tell them about feeling totally, helplessly adrift.

She’d made this life, these choices, and she wasn’t going to give up in the first week. It couldn’t be any harder than moving out of her parents’ house the first time or the weeks of endless training at the CIA, no harder than being in a foreign country with a fake name and a list of impossible goals.

While she ran a hot bath, she dug the list out of her bag, smoothing the wrinkles on the narrow desk. There were only about twelve names on it, and she quickly realized that there were only two female names. Something about moving into the house of a male stranger just seemed untenable.

One of the names included a phone number. The other gave only a faculty office number and office hours. That simplified the matter. She’d call the first number in the morning, and if that didn’t pan out, she’d stake out the office of this Professor Helen Everton and see what she could find.

Chapter 2

The professor who had answered the phone number attached to Annie’s Hail-Mary list apologized and said the room was already occupied. So that was that. As Annie made her way onto campus, she read the list of names again and tried to decide which of the men sounded the least threatening.

Michael R. Darby.

As long as he didn’t go by Mike.

Neal Halfon.

She crossed that one out with her chewed-up pen. The man could be Santa Claus or Jesus Christ or Patrick Swayze, but she could never have a normal conversation with someone named Neal.

Someone brushed against her, and she looked up. She’d wandered into some sort of new-student orientation fair. Tables were set up displaying banners of different clubs and departments. It seemed to be aimed at undergraduates because there were a fair number of parents escorting their wide-eyed teenage children.

Someone at a table beckoned her to come over and check out something called Bliss and Wisdom International.

She looked down at what she was wearing: jeans, sandals, and a pink T-shirt. Oh God, she looked like an undergrad. She veered away to avoid the girl at the table and looked again at the campus map that she’d stapled to her list.

Everton’s office was in the criminal justice building, which meant she taught in that department. Annie paused at the foot of a busy staircase and considered. Did she even want to bother? Would one of her prospective professors even let her rent a room? But Annie didn’t remember signing up for a class taught by anyone named Everton, and maybe she was nothing more than an adjunct professor. Tenure-track professors usually didn’t need to rent out rooms in their houses.

Beggars couldn’t be choosers, and time was ticking down. She had to at least scope this woman out or she might end up living with—she glanced at the list—Aaron L. Panofsky. She’d dated a boy named Aaron once. She crossed that name out too.

Everton might not even be in her office, Annie reminded herself. Classes didn’t officially start until next Monday. She’d already shaken a second voucher out of Paul, but she wasn’t going to get another one, and she was ready to get out of the motel. Plus, she couldn’t avoid calling her parents forever.

She stopped to consult her map and then, leaning against a low wall under the shade of a tree, peered down at the row of buildings. There weren’t many people going in and out of Everton’s building, though plenty of people were walking by. Since all her classes were going to be in this building, she decided to go in and do a little recon. She could walk around until she found the professor’s office.

The dry heat seeped into her like an oven, despite the shade of the tree. She was used to the swampy summers of the Midwest and DC, but the intensity of the California heat was something else entirely. The building beckoned her with the promise of centralized air conditioning.

The first couple of floors were classrooms, and she quickly found the ones where she’d be attending classes. When she climbed the stairs to the third floor, the atmosphere changed. The closed doors were identified with placards. She looked around until she found the room she was looking for at the end of the hall.

H. Everton-323

Compared to the size of the classrooms on the floors below, Everton’s office didn’t look bigger than a glorified closet, barely big enough to hold a desk, two chairs and maybe a filing cabinet, if she was lucky. The office door had no window, so she couldn’t see whether it was light or dark inside, but it sure didn’t sound like anyone was in there. She twisted the doorknob gently. It was locked.

It would be hard to stake this spot out inconspicuously, so she went back the way she’d come in. She had passed a room earlier that seemed to be the department office, and when she passed by again, a woman was sitting at the front desk.

Annie plastered a smile on her face. “Hi.”

The woman glanced up and smiled in return. She wore a shapeless sweater complemented by a frumpy haircut. “Do you need some help, hon?” she asked.

“I sure do,” Annie said in the gushy, saccharine voice she used for church and her mother’s crochet circle. “I’m starting classes here on Monday, and I was just wondering if the faculty start their office hours this week or next.” She leaned in conspiratorially. “I’m not from around here. I’m just trying to get my bearings.”

“Well,” said the woman, “not until next week officially, but most of them will pop in at some point this week.”

“That’s good to hear. I’m Annie, by the way.”

“I’m Deb Larson,” the woman replied. “I’m sure we’ll get to know each other very well over the next few years.”

“A pleasure to meet you. This campus is just so beautiful, and the whole city looks like the movies!”

“Where did you move from?” Deb asked.

“Toledo, Ohio, ma’am,” she said. “It’s not exactly bumpkin country, but it’s sure different from here.”

“I imagine so!”

“Say, do you all do rosters? The faculty, I mean. I’d like to get a sense of who’s who before classes start.”

“No,” Deb shook her head. “But the library has a set of yearbooks. You’ll find faculty photos in any one of them. They republish the same ones every year.”

“Good to know.” Annie grinned. “Thank you so much for your time today.”

“Here to help,” she said. “Good luck, honey.”

As soon as Annie turned around, the smile disappeared from her face. She pounded down the stairs and headed for the door, nearly colliding with a woman carrying a red-faced baby in a car seat. Annie stood aside to let her pass, then pushed out into the heat and sunshine, intent on the library.

The building was swamped with people being issued new student IDs. Since Annie needed one too, she abandoned her plan to find the yearbooks and instead stood in line to get her photo taken, then stood in another line while someone pasted it onto an ID card and ran it through a laminator. By the time she had her card, she was done for the day.

In her motel room, the piles she’d left everywhere had been straightened up by the maid. She called her parents.

“Anabelle Weaver!” her mother chastised. “You have been purposely calling when we’ve been gone!”

“No, Mom, that’s not true,” she lied. “You know it’s earlier here. I just forget about the time difference!”

Annie didn’t want to admit to her mother that her home life was shaky at the moment, so she told her there was a gas leak in the apartment building where she was supposed to live and that they had her and the other students in a motel until it got fixed. The fib slid out far more easily than any truth.

“What happens if it isn’t fixed by Monday?” her mother asked, concerned.

“I don’t know. I guess they’ll keep us on or make other arrangements,” Annie said. “I’ll let you know when I’m settled.” It was a lie so good, she wished it were true.

After hanging up, Annie warmed up a frozen dinner and watched TV until the sun went down. She didn’t think she’d sleep, but even scratchy sheets and the sound of traffic outside didn’t keep her awake. She woke once in the night to use the bathroom, banging her elbow into the doorframe, but then she stumbled back to bed and slept until her alarm went off.

The library the next morning was much quieter, and the girl behind the desk wrote down a call number on a slip of paper and directed Annie to an upper floor.

“They’re toward the bottom, the newest ones,” she said. “I don’t think they get used a lot, but there should be one from last year up there.” She gestured to the large computer monitor in front of her. “We’re still converting everything from cards to a database, so it’s been kind of crazy.”

The yearbooks were tucked away on the lower part of a tall, dusty shelf. Some of them went back well into the 1950s, taking up one shelf on the bottom. The newer yearbooks were one shelf higher. They were slimmer, cleaner, brighter. Annie crouched down, found the one stamped with 1991 on the spine, and pulled it out.

She ran her finger down the table of contents, found the faculty section, and flipped to the back, leafing through until she hit the names beginning with E. She scanned the pictures: Edison, Engle, Epstein, Ettinger.

But no Everton. Not even an asterisk for the not pictured. Was she new?

She slammed the yearbook shut and slid it back onto the shelf.

She was just going to have to figure this woman out the old-fashioned way. Hunker down outside the building and hope she turned up. Look her up in the phone book, see if her address was listed. Annie was good at finding people; she’d been doing it professionally for years now. She’d find H. Everton.

She went back to Everton’s building and sat in the shade on the same low retaining wall where she had sat the day before. She’d checked out a book from the library, and she pulled it out of her bag to use as a prop, opening it to a random page in the center. From this post, she could watch for a while, see what kind of people went in and out.

She should be settling in somewhere, looking for a job, prereading her textbooks, or thinking about her upcoming classes. Buying a binder, maybe, or a pack of pens. Instead, she was doing exactly what she was trying to get away from. God, maybe she’d been wrong to leave. Maybe this really was the only thing she was good at, and she was never going to find anything that suited her better. Maybe she should have learned to live with the things that haunted her: an epic failure, a leering boss who promised her there was nothing in the outside world waiting for her.

A man and a woman went into the building. He held the door open for her. Annie glanced down as if studying her book.

When she looked up again, the man had come out alone. He was of medium height and thin. His black hair was cropped close to his scalp. He wore beige shorts and a powder blue T-shirt. She looked down again, turned the page.

She looked up when someone wearing beige work coveralls steered a squeaky cart along the walkway between her and the building. She watched him until he rounded a bend. The cart squeaked even after he left her field of vision.

Which is why she didn’t notice the stroller or the attractive woman steering it until she reached the wall and the shade where Annie was perched. She turned her head to peer into the stroller at the sleeping baby, soon realizing it was the same baby she’d seen yesterday, the one in the car seat. Of course, it was the same woman who’d been carrying it.

The woman pulled the stroller parallel with the wall, then set down her purse and began rummaging through a beat-up brown diaper bag that she was holding against her hip. Her bobbed, dark brown hair reflected auburn in the sunlight and fell forward, obscuring her face except for a pair of wire-framed glasses with large lenses that peeked out between her locks. She wore scruffy clothes.

Annie returned her attention to her book, still watching the woman from the corner of her eye, not looking up until the woman said, “Shit!” The bag had fallen to the ground, its contents spilling everywhere.

The woman sat down on the wall and looked at the mess. Only the stroller separated them; the baby slept tucked under a light blue blanket.

“Here, let me help.” Annie set her open book down on the wall, spine up.

“It’s okay. It’s fine. I’m fine,” the woman said, shaking her head. She rubbed her hands on her jeans and half closed her eyes.

“How old is he?” Annie asked, nodding toward the baby as she crouched and started picking things up—a gold tube of lipstick, a tampon, a crumpled receipt.

And an identification badge with the woman’s picture attached to a lanyard. The woman hopped off the wall and snatched it away but not before Annie read her name and title.

Helen Everton, Adjunct Professor

Annie handed Helen Everton the items she’d picked up, forcing the woman to stop jamming things back into her bag. When she accepted them and everything was back inside, she gave it a good shake.

“Four months,” she finally said, reaching down to pick up her purse. “Almost five now.”

“He’s beautiful.” And it was true. The baby, light-skinned with a tuft of dark hair, was sleeping peacefully.

“Thanks,” she said. “He’s colicky as hell.”

Annie started to laugh and then caught herself. “He your first?”

“Third.” She shook her head, her hair swaying with the movement. “No. I mean, I have two of my own, but he’s a foster baby. I’ve only had him for six weeks, and we’re still getting used to one another.”

“Wow,” Annie said. “How old are your other two?”

Everton pushed up her glasses and rubbed at her face. She had no makeup on. She looked tired.

“Eight and ten.”

“So you have your hands full,” Annie glanced at the entrance to the building.

Everton smiled thinly, then hefted the purse onto her shoulder and picked up the diaper bag.

Sensing that Everton was about to extract herself from Annie’s invasive questions, she searched for something to latch onto. Just one small fact about Helen Everton that she could exploit for her own gain.

“I’m Annie, by the way,” she said. “Just so I’m not a complete stranger. At least you know my name.” She resisted the urge to stick out her hand, thinking Everton wouldn’t take it.

“Annie,” Everton repeated. “Thanks for your help.”

She started pushing the stroller toward the building. As much as Annie wanted to keep talking to her, she didn’t want to scare the woman off.

If they went into the building, they’d have to come out again.

They came out much sooner than Annie expected. She’d waited five minutes and then ran into the building to use the first-floor restroom, certain she’d have to sit for a couple hours, waiting for Everton and the baby to emerge once more. But forty-five minutes later, Everton came out, holding the wailing baby and a bottle. The baby’s cheeks were bright red in the sunlight.

Annie had moved away from the retaining wall and was sitting on a patch of grass far enough away that the woman wouldn’t see her immediately when she came outside again. Sometimes an extra few seconds of observation made the difference between a successful contact and a failed one.

Everton was trying to soothe the child, but the cries were getting louder. Annie closed the book on her lap and squinted. After watching for a few moments, she put the book away, slung her bag onto her shoulder, and approached Everton.

“Hi again!”

Everton looked at her, her expression confused at first and then annoyed.

“Is he okay?” Annie asked.

“As I mentioned.” Everton bounced the baby, “colicky.”

“I bet he’s just overtired,” Annie said. “I have, like, a bunch of younger cousins and a baby niece.”

Everton nodded distractedly.

“He doesn’t want to eat?”

“Oh, I don’t know.” Everton’s voice was tinged with exhaustion. “He never wants anything.”

All at once, Annie saw everything she needed to know about Helen Everton. She wore her hair in a sensible shoulder-length bob. Her light-wash jeans showed signs of wear. Her button-down shirt had a small stain at the front hem, like it had accidentally been dragged through someone’s dinner plate. Her loafers were scuffed, and her purse strap was fraying.

She was an adjunct professor, so she probably wasn’t making a lot of money. And while her clothes were well-made, they were old and worn, suggesting she’d had money at one point but was living leaner these days. She was a mother, but the third baby was much younger and a foster baby. Had she had a change of heart? Was she helping out a family member or friend who had lost custody? Or was she in it for the money that the state paid foster parents?

Annie decided to see if she could get Everton to trust her.

“You look like you could use a break. Want me to hold him for a minute?”

Everton, who’d been spinning in place trying to calm the baby down, looked over at her with suspicion.

“I’m not going to steal him. I’m a really slow runner, I promise. But I am good with babies. Even colicky ones.”

Everton studied her a moment longer, then with one more ear-piercing wail in her ear, she decided to trust this complete stranger and shoved the boy into her arms.

Annie couldn’t quite believe the woman had agreed, except for the fact that getting people to trust her was something Annie had always been good at. Still, it never ceased to amaze her. It was a game now, in a way, to see how much she could get someone to hand over to her and how quickly. Today it was a harried woman and a foster baby.

The shift was enough to startle the boy into a moment of silence while he reassessed his environment. Annie snatched the bottle before he could begin crying again and put the nipple to his lips, guiding it in and praying that the lie she had spun about being good with children was going to pay off.

She’d had a younger brother, but she’d been only two when Danny was born, so she didn’t really remember having a baby in the house. Still, how hard could it be? Feed them, let them sleep. Change a diaper every once in a while.

As luck would have it, the baby started sucking at the bottle greedily, quiet in Annie’s arms.

* * *

Annie’s first out-of-country assignment had been five years ago in St. Petersburg, though it was known as Leningrad back then. She wasn’t sure she could ever think of it by any other name. The CIA had been eager to take advantage of perestroika, Russian Premier Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy reform. Her bosses thought that the restructuring of the political and economic systems would open new leads for informants.

Annie joined the CIA at the height of this disaster. She didn’t know that, of course. Most of the turmoil was internal, and they recruited hard that year—visiting universities across the country, promising good pay and a life of excitement.

Annie hadn’t seen the recruitment flyers or heard anything about it, though. She’d been studying economics, considering a possible career in finance, or perhaps becoming a high school teacher. Her mother had taught in an elementary school for a few years before she married Annie’s father. It never occurred to her that she could work for the government or that they might want her.

She didn’t go to the recruitment session, but a recruiter sat in on one of her Russian classes. Annie was almost fluent in German, having taken it in high school, and she was tearing through Russian, listening to language cassettes in her spare time and reading ahead in the textbook. She liked languages; it was like doing puzzles backwards. They were exotic and beautiful, and she liked taking them apart piece by piece.

They had done an exercise that day, performing little conversational skits at the front of the class. Annie was grouped with another woman and a young man. The man was the weak link, fumbling through his lines, sweaty and embarrassed.

Acting was just another language to Annie, and she could spout off simple phrases without effort.

“Dobriy vyecher,” she said. “Meenya zavoot Annie.” The male student was struggling, and she fed him his lines in a stage whisper, causing the rest of the class to laugh through their three-minute performance while the professor scowled and scolded them.

When she went back to her seat, she noticed the man in the dark suit watching them. She noticed him again when she went outside.

“Annie,” he said as she passed him. “Tebe nravitsya puteshestvovat?”

“Sorry?” She understood the question, but she didn’t understand why he was asking it.

He continued in Russian, asking her if she was proud of her country. His pronunciation and accent were perfect, but she could tell he wasn’t a native speaker.

“My father’s a lieutenant colonel in the army,” she answered. “You won’t find a more patriotic person than me.”

It was a good sales pitch; the recruiters had it down to an art form. She didn’t need much convincing. The background checks were inconvenient, but the worst things on her record were a few parking tickets and some detentions in high school for talking too much during class. She said yes when they offered her a job on the day she graduated. Drove out to Virginia with her father; he tried to talk her out of it the whole way. He had spent his career employed by the United States government and knew well the ups and downs, but his jaded warnings could not overcome the high of being wanted by her country.

It wasn’t until she was mostly through her training that she realized why the CIA was so desperate for agents; everyone they had in the Soviet Union had disappeared and they didn’t yet know why. Would they assign a green twenty-one-year-old to the Soviet–East European division? Surely not!

They did hold her back, for over a year, because she excelled at basic interrogation, and they wanted to beef up those skills. She also took Czech along with more Russian-language classes. In a lot of ways, it was like she’d never left school, only now they were paying her instead of her father writing checks.

Annie landed in Leningrad completely fluent in Russian and German, close to fluent in Czech, and with orders to pose as a university student. She was to look for political students ready to turn on their country and for the wealthy children of known KGB agents. They also told her—informally—that if she could figure out the leak, that’d be great.

Twenty-three, first time out of the country, in over her head.