Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

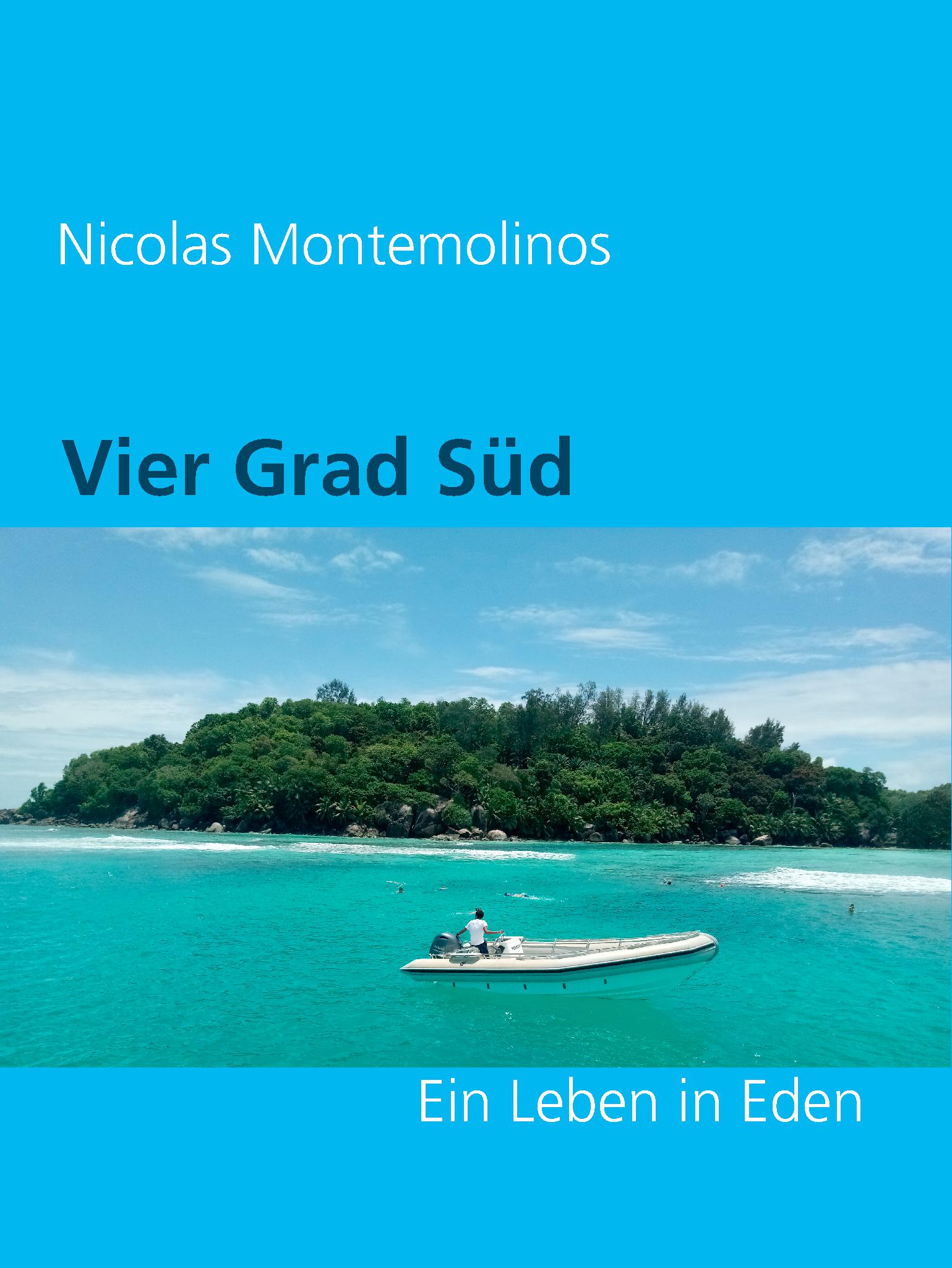

Close to the equator, west of the state of Ecuador, lie the Turtle or Galápagos Islands. One of these — not very large — is called “Floreana". Several hills rising about 1800 feet above sea-level. Lava-extinguished volcanoes; hard, loamy soil; a bay on the west side and one on the north; plains covered with impenetrable bush; lemon and orange groves; two poor roads; a little sweet water; some swamp-land; several dilapidated caves once used by pirates; the house of two German emigrants: Dr. Frederick Ritter and his young and sexually explicit mistress Dore Strauch. In 1932 Margret Wittmer, the famous "Queen of Floreana", her husband Heinrich Wittmer and her stepson Harry also emigrated to Floreana. Dr. Ritter didn't survive these new settlers. Was he murdered? The death of Dr. Ritter still remains one of the greatest mysteries in the history of Galapagos. This Ebook tells the truth about the exciting lifes of Margret Wittmer and Frederick Ritter.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 629

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Two Strange And Scandalous Galapagos Stories - IntroductionStrange Story No. 1Comment Strange Story No. 1Strange Story No. 2Comment Strange Story No. 2ConclusionImpressumTwo Strange And Scandalous Galapagos Stories - Introduction

Nicolas Montemolinos

TWO STRANGE AND SCANDALOUS GALAPAGOS STORIES

Introduction: By the 1920s, Europe was weary of war. Many on the continent began to dream of finding a place where they could create a peaceful, idyllic life for themselves. Two events came together to convince some of them that they would be able to find it in the Galápagos: the publication of American naturalist William Beebe’s bestselling 1924 book titled Galápagos: World’s End, and the Ecuadorian government’s offer of free plots of land with hunting and fishing rights and no taxes for ten years to anyone wishing to settle there. One such European was Dr. Frederick Ritter, a German dentist, philosopher, and vegetarian. He longed to indulge his raw food theories and work on his theosophist — a “hidden” science that attempts to reconcile scientific, philosophical, and religious disciplines into a unified worldview — treatise in the company of his devoted disciple and girlfriend, Dore Strauch. He decided that the Galápagos would make a perfect base for those endeavors. They arrived on Floreana Island in 1929. Over the following three years, Dr. Ritter wrote letters back home, which became highly popular (Strange Story No. 1!). Much to the Ritters’ disappointment, however, the popularity of their story began to draw other would-be inhabitants to Floreana. In September 1932, Margret and Heinz Wittmer of Cologne, Germany, came to Floreana. Like others before them, they came for a more peaceful lifestyle and to avoid post-war Germany’s financial meltdown. But unlike most of them, the Wittmers were extremely successful at agriculture and stayed on. The reception by the Ritters, unfortunately, was cool. Margret and Heinz Wittmer were down-to-earth types, while Dr. Ritter believed his philosophical rhetoric was beyond the intellectual levels of the island’s newest residents. After Ritter's sudden and horrible death Margret Wittmer took control on Floreana Island and was named "Queen of Floreana" (Strange Story No. 2!).

In 2013 the Kindle Bookstore at amazon.com published two eBooks ("My Evil Paradise Floreana" and "The Queen of Floreana") pertaining to the human history of the Galápagos Islands. Since both were highly distorted versions of reality, the two scandalous books were heavily criticized. In the end, the books were suspended in May 2015. But censorship isn't a good thing at all. So both books are quoted and commented upon below:

Strange Story No. 1: "Frederick Ritter My Evil Paradise Floreana" by George Egnal

Figure 01 and 02 above: Title page and “Ritter” cover—a copy of a photo taken from Ritter's "Als Robinson auf Galapagos", with added coloring.

All rights in this book are reserved. No part of the book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. Copyright 2013 by George Egnal

FOREWORD

In 1930, Floreana Island, just a few miles south of the equator, was supposed to be uninhabited. But this wasn't true, because German doctor Frederick Ritter and his girlfriend Dore Strauch lived here. A few month before, Dr. Ritter abandoned his practice and his wife Mila Clark in Germany. He migrated to the Galapagos Islands, feeling he needed a new start in a faraway place with another woman in order to develope a new kind of philosophy based on illumination in solitude. They set up a homestead on Floreana Island and worked very hard there, moving heavy lava rocks, planting fruits and vegetables and raising chickens. There home was well inland, about an hour's march on a faint trail through the desert brush and over broken lava rock. The two Germans had come to the island well supplied with food, but the shortage of water forced them to leave the coast and to move to the mountains. They had left most of their stores in a cache near the beach. These stores were stolen by men from some vessel, perhaps a fishing-boat. Without medicines or antiseptics, with no guns, very few tools and almost no food, Dr. Ritter and Dore were in a bad way. She had fallen on the sharp lava rocks and had cut her knee to the bone. This almost disabled her. He had injured his arm and side in a fall through the branches of a tree. The red-bearded doctor, about fortyfour years old, and the young and beautiful girl tried to find a paradise on the island. But their efforts to create an own private Eden failed. Unfortunately, Dr. Ritter died. After his tragic and mysterious death Dore Strauch returned to Germany. A friend urged her to set down the account of her experiences on the island and her brave life with the man for whom she left home and friends. This book tells the marvelous and fascinating story of Dr. Frederick Ritter's adventurous and exciting life on Floreana. It is published to the memory of this famous and important philosopher, whose grave is on the island but who is still alive in our hearts.

A NEW LIFE FULL WITH DREAMS BEGAN

Here follows the extraordinary tale of Dr. Ritter told by his companion Dore Strauch:

I was a very happy child, and in everything I have since experienced, I have never ceased to thank my good parents for letting us be children so long. Although my father was a schoolmaster, he never pressed his children into a set system of upbringing, as so many educators do, and my mother has always shown me that instinctive understanding which certain people are gifted with, and which enables them to grasp with their hearts things that are often obscure to their minds. All my life I have liked to think back upon my earliest years, and if my most vivid remembrances of that time are concerned with animals rather than with people, the reason is perhaps that I have always felt a special intimacy with so-called dumb creation which is, I think, unusual in one born and brought up in cities. I remember as a four-year old spending a holiday with my grandmother on a farm, being told that the big watch-dog had to be chained up by day because he was very savage. But on the same afternoon I called upon him in his kennel and told him I had come to keep him company. We told each other many things, and spent a delightful afternoon, at the end of which I was discovered side by side with my new friend fast asleep inside the kennel. Thirty years later my little donkey friend on Floreana once reminded me of that old watch-dog, Pussel, and other animal companions of my childhood with whom I had been able to talk as I never could with human beings, and who, no matter how they often seemed to dislike other members of the human race, were always ready to be friends with me. It must not be thought that I was one of those strange and solitary children who seem unable to adapt themselves to their environment; on the contrary, I was always glad to play with anyone my own age, and cannot remember that I was ever very different from my playmates except in one respect, and that only as I began to grow a little older. A feeling then began gradually to take root in me that I was somehow not like other children, and I found myself going my own way, as though I had no real part in their lives, but had to lead a life of my own. When this feeling became really strong I was no longer quite a child, but of an age when ideas acquire the importance of actions, and take up the most part of one's thoughts. A kind of conviction grew in me that there was some task which I was born to fulfill, although I had no notion what it could be, and no real understanding of what a life-work meant. I only knew that it was something great, and in a way I cannot describe I was always looking for it. The years went by, and life was no longer a time of calm or ardent meditation. I had begun my training as a teacher. The Revolution of 1918 broke out. It had no more passionate partisan than I, then in that stage of my own personal development when all the ills of the world seemed to be solved only by violent and radical outward measures. The proletarian movement revealed to me so many things of which I had not dreamed before, that I was plunged into an extreme of zeal for contributing in whichever way I could to the amelioration of the frightful distress among the German working-classes. This socialistic phase is one that almost every person goes through, and I, like many others, enrolled myself in the voluntary service of the poor and poorest with the religious enthusiasm of my age. My experiences at that time certainly influenced me deeply, as an aspect of life was unfolded before my youthful eyes which left me gazing at it in helpless despair. These things all turned my thoughts to the subject of the higher development of mankind, and realizing, in the face of what I had seen, that this can never come from the outside, I sought the way towards it from within. It was Nietzsche's Zarathustra that became my teacher and my guide. I set out to remake my life according to its precepts, and then began that struggle against evil instincts and passions, which I determined to wage victoriously, whatever the cost. I finished my teachers' training course, and passed the examination, but found no immediate appointment. Having to earn my living at something, however, I accepted the offer of a post in one of the large banks. Although I completely realized that social work was not my vocation, my desire to help my fellows rather increased than diminished. I thought that in order to achieve this ideal I might become a doctor, and, undeterred by the prospect of seventeen hours' work a day, I enrolled myself at a night-school to study for the university entrance examination. I might have stood the strain of all this better, had I not chosen that time for confining my diet exclusively to figs. It was my reading of Schopenhauer which inspired me with this idea to live on fruits, discountenancing the destruction of life for human nourishment. The year and a half of this regimen, so unsuitable considering the great strain my double work put upon me, sufficed to weaken me to such an extent that one or the other of them had to be abandoned. By this time I had arrived at the age of twenty-one. Among our family friends was the principal of a high school, a man of forty-five, a very grave, sedate person, who had long since reached all his conclusions. Nature had blessed me with a very happy temperament, and I began to see that the cheerfulness and gaiety which my somewhat melancholy father had always treasured in me, also seemed able to charm the earnestness of this other solemn man, so much too earnest for his age, and lure him out of himself. His personality attracted me, and I thought it would be a work worth doing to thaw him out with sunshine. I never doubted but that it would be easy to overcome the deeply-rooted peculiarities which had grown upon him during his long and cheerless bachelor life, and lure him to a cheerfulness which he had apparently never known. I thought it would be splendid to make him young again, and happy. One October day he asked me to marry him; I accepted and was very happy. It was not my parents' way actually to oppose their children's decisions, and so they brought no pressure to bear in order to dissuade me from entering into a marriage the prospect of which so obviously delighted me. But they did not hide from me their own misgivings; for not only did the disparity between my age and my future husband's seem ominous to them, but their experienced eyes foresaw that either my light-heartedness would be extinguished in his gloom, or else that the day would come when I should revolt against it. In either case they felt that this marriage could come to no good end. The wedding was in April, and I at twenty-three became the wife of an elderly schoolmaster. My husband was, I found, extremely thrifty. For half a year we still occupied no apartment of our own, but lived in furnished rooms, I, at his wish, continuing my work at the bank. These were the years of the German currency inflation, and I received a good salary. Nevertheless it seemed strange to me that I should still be required to go to work, when I had a husband well able to support me. It was not I who rebelled, however, but my health. I broke down completely. The next seventeen months I spent in a hospital where the doctors diagnosed my illness as multiple sclerosis. The lameness which afterwards became permanent, attacked me at that time. I had greatly desired a child, but now had to undergo an operation which made this forever impossible. I do not know whether this really had to be or not, but I do know that when I learned that I could never become a mother, something inside me broke and gave up hope. I became well again, and could leave the hospital, but the doctors told me that my illness was incurable. This was a blow, but it shocked me less than the realization that my marriage was a failure, and beyond repair. Like countless other women who enter marriage in what is called a state of innocence, the conjugal relation had offended and repelled me. But I had hoped to save what there was to save of a marriage blighted at the outset, and overcame much inner bitterness and rebellion in the attempt. It was all in vain. For it was not, as I had thought, I who was to make a different man of my husband, but he who had determined to make a different woman of me, conformable with his ideal - the petty, bourgeois ideal of the German man on which the German woman has been content to model herself down the ages - the "Hausfrau," (housewife) her horizon bounded by the four walls of a few stuffy rooms, her mind stunted to the scope of her husband's paltry opinions. With all the strength and obstinacy in me, I defended myself against being turned into something I had always passionately despised. At the same time, it grieved me to think that I was as disappointing to my husband as he to me, and I did all I could to make this up to him by opposing him outwardly as seldom as possible, and in not letting him see how little of my life he really shared. But the emptiness and frustration of such an existence poisons the spirit, however one may strive to counterbalance it. Having been so mistaken in my attempt to devote myself to one man's life only, I began to return to my former idea that I was meant to work for the general good, and decided to go on with my preparations for studying medicine. My husband did not oppose me; in fact, for all his lack of skill with me, he never ceased to be, in his own way, a generous and devoted friend. Perhaps this praiseworthiness in him became more clear to me in later years than it was then, but even at that time I felt grateful that he did not hinder my studies. I found a refuge in the fact that my illness necessitated much time in hospitals, during which time my husband did not seem to mind his loneliness. I could thus use the time to study without having to rebuke myself for playing truant. One day, while I was receiving a ray treatment, a young-looking doctor came through the room. He struck me particularly because of the deep furrows in his forehead and the extremely harsh expression of his eyes. It would be too much to say that he looked brutal, but there was a strange absence in his face of any trace of amiability. It went through my mind that I hoped I might never have to be examined or treated by him. This was in the Hydrotherapeutic Institute, a department of the University of Berlin clinic, where I was again a patient. This same doctor appeared frequently in the ward, among the group of assistants who accompanied the head physician on his visits, so that I had leisure to observe him closely. He was not tall, but very slender, and moved with extraordinary litheness. He had a great deal of fair, curly fair, and his eyes were very blue. One day, during the afternoon visit, the new doctor, passing from bed to bed, asked whether any of the patients had any special wishes. He came and sat beside me, and we talked. Our talk was about the power of thought. He told me that even I need not submit to illness if I would learn to think in a way that would make me well. He spoke of certain books, and offered to lend me some. It was thus that I came to read the works of Mulfort, which have influenced me so much. I found in them to my delight a conception of life and of the world which was my very own. From this time on, Dr. Ritter came every day, and talked to me as long as he had time to spare. We felt our way carefully into each other's world, and something in each of us knew that it had found its affinity in the other. I had been ten days in the hospital when I was discharged as greatly improved. It was necessary, however, for me to continue in the care of a physician, and Dr. Ritter asked me if I would like to come to him in his private consultation hours. I did not then know that he had already detected the mental stress behind my physical sickness, but I felt a longing to talk to him, to unburden myself of all the problems and difficulties which beset me and destroyed my peace of mind. The burdens and conflicts of my life were becoming more than I could bear in loneliness and silence any longer. I said to Dr. Ritter that I should be glad to come and see him, and went, with the firm intention of telling him everything without reserve, as to a confessor. I found it a strange but delivering experience. He asked me if I were not happy in my marriage. I assured him that I was. One day he took me home, and as I said good-by to him at the gate, my husband appeared at the window, and came down to open the door to me. Dr. Ritter, who had gone a few steps down the street, turned and came back. "It would be cowardly not to show myself," he said. I introduced him, and we went into the house. "Is this man really so much interested in your illness," asked my husband afterwards, "or is he in love with you?" I did not know how to answer this, so I said nothing. After this I walked with Dr. Ritter every morning through the Tiergarten to his clinic. We had a feeling that we were intended for each other, and that there was some work we had to do together, as though we were a joint tool in the hand of a spirit using us to unknown ends. One day he kissed me, and then he said to me, "I wonder that I could do this, for I love some one else." I said, "That makes no difference,"for to me the chief thing was that he accepted the love that I now knew I felt for him. He told me that he loved a girl twenty years his junior, his own niece. This was a romantic, idealistic love, scarcely returned and certainly not comprehended by the girl herself. But I could feel no jealousy of her or any other woman, for neither man nor circumstance can come between two who have been predestined for each other. Dr. Ritter was scarcely more than a youth when he first began to feel that the life of contemplation, through which alone the human spirit can perfect itself, could not be led in the populous places of the earth. He was not by nature a man who shunned others, that is to say, there was in him nothing of the misanthrope. But the complexity and ultimate untruthfulness of ordinary human relations seemed to him to take up too much of life and to disturb the crystallizing of that philosophy which each great thinker evolves for himself. As a physician, greatly interested in and very gifted for his work, he was forced into a continuous contact with people that could not but become increasingly irksome to a mind fast reaching its philosophical maturity. At the time our friendship began, he had arrived at the point where he was ready to make a great decision, and that I came into his life just at that moment neither of us ever thought was merely an accident. I will not go into the details of Dr. Ritter's philosophy. He has in introductions to his own writings done this much better than I ever could. But it is necessary perhaps, in order to give a clear picture of him at that time, to say that it moved between two poles, with Nietzsche at the one end, and at the other Laotse. Nietzsche, the great prophet of the will to might, with his dynamic force and glorification of the Superman, his heroic vision of the universe and his ideal of power, could not fail to inspire a man like Dr. Ritter, himself endowed with so many of these highest qualities. It was this element of the heroic in Dr. Ritter which made the most profound impression on my mind; for as long as I can remember, I had felt drawn to everyone who seemed by nature somewhere in the neighbourhood of greatness, whether he had it in himself or only in the degree with which he reverenced it in others. Surely no mind of lesser stature than Dr. Ritter's could ever have reconciled the active ideal of a Nietzsche with the gospel of inactivity and passive contemplation embodied in the precepts of the Oriental master. From the beginning of our friendship, Dr. Ritter had admitted me into his inner world. He never made me feel that in comparison with him my understanding of all these high problems was elementary and primitive; on the contrary he took the greatest pains to develop me and show me the way along paths which he had blazed for himself. He was never tired of telling me with what joy he had recognized in me from the very first a fellow pilgrim on the way to final wisdom. Our happiest hours together were spent in unforgettable and endless talks during which I sat at the feet of this man who looked on me as his disciple. Dr. Ritter had an extensive and successful practice in a quiet West End street, Kalkreuthstrasse. All kinds and conditions of men and women were his patients, and he was much beloved by them. During the strenuous consulting hours he would sometimes steal a little time for me, and then we would go up on the roof of the house and talk. Gradually the plan to go away took definite shape in his mind and there, overlooking the close-packed roofs of houses where human beings herded together with insufficient air and space to move and think in, he mapped out his idea of a permanent migration to some remote spot on the earth's surface, where he could realize his great ideal of solitude. We lay up there in the sun letting our fancy wander where it would, pretending that the clouds that drifted by were our remote island of refuge and the blue sky the ocean in which our earthly Eden was set. Dr. Ritter had a little black book in which he had noted the earth's remotest archipelagos and single islands. We would pore over these and he would tell about them until we felt that we were there. But into the midst of our dreaming would come a whistle from the landlady, a signal we had improvised to announce the arrival of patients. I had now begun to share Dr. Ritter's life in every way and it was my hope that I should go on doing so forever. He was actually, though not legally, separated from his wife, while I was by no means separated from my husband and had a difficult situation to handle at home. Dr. Ritter, realizing that my domestic situation became harder, not easier, as time went on, suggested that I become his assistant so as to give respectability to our daily association. I, however, rejected this idea completely. It was not in me to cope with the deadly routine of a doctor's office, and besides this, I could see that such an arrangement would end by strangling us in bonds like those of ordinary marriage from which it is so hard ever decently to escape. If I was to do my share in making this man happy, and if I had any happiness to expect from him, then it could only be in conditions entirely different from those that I had experienced in marriage - quite free, untrammeled, and from first to last unconnected with any preconceived ideas of bourgeois home-making. Up to this time I had suffered great pangs of conscience even at the thought that I might leave my husband. On the other hand, it had never occurred to me to keep him in the dark as to my feeling for Dr. Ritter. In fact, as soon as I found out I loved this other man, I told my husband so. He furiously forbade my seeing Dr. Ritter any more, but when I refused to comply with his wish he quietly accepted my decision, and the daily walks through the Tiergarten were continued. There were no scenes between my husband and myself. I should have respected him more if there had been. While I despise women who regard their function as their husbands' cook and child-bearer as the whole of life, I still believe that a proper man must be the master in his own home. Women's lack of emotional control keeps them nearer the earth than men, and we can overcome our earthiness only if we have a man beside us, helping us and controlling our lapses. My experience on the Galapagos Islands with Baroness Wagner-Bousquet confirmed me in this theory. She was the archtype of a woman dominated wholly by feeling and the most primitive urges; and of the young males with whom she was surrounded, not one was man enough to make his curbing influence felt. How different was the life which Dr. Ritter and I led on Floreana! Ours was an attempt entirely to stifle the animal in us wherever it interfered, as it so often must, with mutual happiness on a higher plane; and, wherever the emotional threatened to disturb our mental harmony, to rescue this at the cost of the other no matter how hard that might be. For myself I must confess that the victories I achieved in my own struggle to intellectualize the emotional side of our relationship were dearly won. It was a painful shock to me to have to admit that my legal husband's striking tolerance sprang from the fear that any action on his part would bring about a public scandal, and not from any higher or more generous sentiment. While I could not accuse him of not loving me, it hurt me to think that such a purely practical consideration could outweigh the normal resentment which must have filled him. But this is the way of conventional married life with its mean compromises and essential untruths. The fascination of Dr. Ritter's personality had caught and held me from the first. But love, in the ordinary meaning of the word, does not convey the many-sidedness of my feeling for this man with his astonishing blond mane, his youthful bearing, and his steel-blue eyes that looked out from under his furrowed forehead so compellingly. He was so vital that I never felt any disparity in our ages - he was fifteen years older than I - a thing which, in my husband, I had always been depressingly conscious of. I felt that time could have no power over such dynamic strength as that, and "age" in terms of years had no significance in the case of this truth seeker, progressing smoothly and surely by intellect along the way which I had gropingly sought, and already so far ahead of me. I think it is quite a mistake to say that "love is blind." I know that mine was not. I know that for the sake of his great mind and spirit I tolerated more in Dr. Ritter, I made more compromises in order not to hinder our great mutual quest, than most women would in relation to any man, and I certainly in relation to any other. For in his human contacts he was rough and unskillful, and the fact that one was a woman - perhaps the only woman he did not despise - entitled one to no special clemency or favour at his hands. In my husband's eyes I was the victim of hypnotic suggestion. He even attributed the sudden, rapid improvement in my health to the same influence. And indeed under the spell of Dr. Ritter's powerful assurance that I could be well if I would will myself to be, my health had become incomparably better than it had been for years. It was Dr. Ritter's teaching that one of the dangers of chronic malady is that it brings about, if we allow it to, a degeneration of all healthy instincts both physical and moral, and that this is the peril every patient is morally bound to fight against. "If ever we are called to account by God," he used to say, "He will not ask what earthly deeds we achieved, but what we made of our own selves." One day I hesitantly confessed to Dr. Ritter that I could never have any children, but he consoled me, saying, "Children are an extension of the personal into the world matter, a postponement of personal redemption and of the fulfillment of the ultimate duty laid upon every person to perfect himself." Fatherhood, he said, was one of the ordinary human joys which he had long since renounced. I recognized now that the Ego, always dominant in woman, must be overcome by me in myself, still bound by many ties to earth. I was to find myself in self-abnegation. I prayed that my body might become the vessel of the beautiful and divine so that my life be filled and fulfilled. How few, if any, of the millions struggling along the world's ways, have ever had or sought the opportunity to find themselves. The leisure after the day's work is not devoted to this higher learning. Time that the wise would spend in meditating on these things is spent at movies, cafes and theaters, created as if by malicious design to hinder contemplation. Frederick and I rejected all these things and were determined to fight our way to inner freedom in spite of all the hindrances of civilized life. His logical and abstract way of thinking was a revelation to me. It opened up a new world, a world which even this daring and adventurous thinker had not yet explored, and I realized from the start that unless I was prepared to impose upon myself the most rigorous self-restraint and discipline, I never could expect to keep pace with him. I felt in him the triumph of the masculine and was determined, in order not to fall by the wayside, to subjugate the eternal feminine in me as far as possible. Not that the normal relationship between man and woman should be quite rejected. It must, however, not dominate the situation. "I cannot have a love-sick woman full of romantic notions trailing after me into the wilderness" Dr. Ritter used to say. This was in the early days, but gradually he saw that I was ready to take whatever the great plan brought with it, and after a while this objection disappeared and he became reconciled to the idea of my accompanying him. I often think, indeed I am quite sure, that this experiment, with the idea of which he had been dallying off and on for half a lifetime, would never really have been embarked upon but for my insistence. I felt at the time that not my will but a stronger will outside me was urging me to help Frederick to do this thing; and although in the eyes of the outside world it began in stress and ended in tragedy, I still know that it was the right and only thing for us to do. It reconciled me greatly to Frederick's absolutism when I learned that he was as merciless a taskmaster to himself as for me. His harshness was not personal, therefore I must not take it personally. If he demanded sacrifice of me, his own life was also sacrifice. If he demanded discipline, his own self-discipline was greater than mine would ever be. He reminded me of the prophets of the Old Testament and indeed there was always about him a kind of halo that came from his unalterable and passionate beliefs. He was a John the Baptist who sought the wilderness, not in order to chastise the flesh but to illuminate the mind. His life was not bounded by its span on earth. He is as living to me now, and my belief in him is just as vivid and intense, as in the days when we were together. While some have thought him an eccentric, I know that he was one of the world's geniuses, although his name may go down in obscurity. He might have been a prophet but he was not morose - sometimes he could shed Elijah's mantle and be very human. He often enjoyed company and was much liked. I have already said that his patients were all fond of him, and they seemed to have as unbounded confidence in him as I myself. He used to tell them that he did not like sick people, and wherever he encountered a case which defeated his attempts to bring about an effort of the "Will to Mend," he would give it up rather than nurse it along like a dead weight. He used to apply his own special method of suggestion to every case, and had infinite faith in the possibilities of will-power. It was his opinion that modern civilization had cast the wholesome will with which everybody is endowed into neglect and degeneracy, substituting money for it and bolstering up its feebleness with convenient substitutes. A man of such productive intellect was bound to have a thousand theories of his own about everything, and to enjoy expounding these to others. Dr. Ritter was no exception to this rule, but he was indeed an exception in being at least as good a listener as a talker. His theories often seemed bizarre to many, but this was because he had the courage to push every idea to its logical conclusion, a point beyond which almost all thinkers have lacked the courage to venture. The intrepidity with which he could look things squarely in the face, utterly despising evasiveness and compromise, was perhaps Dr. Ritter's most notable quality. Among the usual run of people it is clear that a man like that would lead a lonely life, and often be forced into the belief that everything was against one who tried to live in absolutes where everything and everybody else lived solely by the grace of compromise. This had been, in a lesser degree, my own experience too, but I think that neither Dr. Ritter nor I ever tended to become melancholy for want of being understood. It was part of Frederick's creed to lead a life of absolute simplicity, but he never attempted to make proselytes for this or any other of his ideas. Much of his medical research centered round theories of diet. He believed that the problem of dietetics once solved, one would have gone a long way towards eliminating half the illnesses human beings are heir to. He had worked out a dietetic system for various social classes. Though he himself was a vegetarian because he found that this form of nourishment was best suited to his type of labour, he included meat in all the tables he drew up for people of the working class. I quote this only as a very small example of what I think was the rather rare quality in him, of never riding his ideas like a pedant but always modifying them and adjusting them to various needs. I sometimes look back in amazement at my life during the two years of my association with Dr. Ritter before we left for Galapagos. In my own home I was still obliged to play the model Hausfrau, appearing with my husband at social functions wearing evening dress and high-heeled shoes. With Frederick I was an entirely different being, even in appearance. The clothes I wore with him were simple in the extreme and had no regard for any fashion, but only for comfort and freedom of movement. More than almost all of what he called the evil inventions of modem costume, Frederick disliked the civilized shoe. He had a different idea of proper human footwear, and made us each shoes of soft leather without heels, sewn to the shape of the feet. We often wore these when we went on walks together. Compared with my life, Frederick's had been rich in experience. His father had been the burgomaster of Wollbach, a little Baden town, and at the same time a prosperous tradesman. Frederick had a sheltered, happy youth, and all the advantages of a good education. An instinctive love of nature led him to prefer the out-of-doors, which was as great a benefit to his rather delicate constitution as to his youthful mind. As he grew up he often accompanied his father on hunting expeditions in the Black Forest. His mother was a lovable and kindly woman, and the family life was perfectly harmonious. At the University of Freiburg his special subjects were chemistry, physics and philosophy, until he took up medicine. He had married while still almost a boy, only twenty-one years old. His parents had objected to the match, but the young blond girl preparing for a singer's career had seemed like the personification of his ideal of womanhood, and he had married her. He felt that he must help her on her way to fame. He had means enough to see that she had the best masters and he saw to it also that she worked relentlessly. He was the stern overseer of her studies and very soon obtained for her an engagement at the Royal Opera at Darmstadt, where she sang Carmen, Mignon, Amneris and many other roles. It reacted badly on the harmony of the marriage that Frederick had a character of extreme aggressiveness while his wife tended to be wholly passive. The war came and Dr. Ritter enlisted as a volunteer. When he returned to civil life he found that his wife had only one desire - to give up her career and devote herself entirely to home. Her ideal was an orderly life with regular routine, and so she managed to persuade him to continue his studies and establish himself in a profession. When I met him he had not long completed his course in dentistry and medicine, and had been married eighteen years. It would not fail to seem to his wife that in the conventional sense I had appeared upon the scene to snatch her husband from her just as her dream of life with him was about to be fulfilled. I was extremely unhappy for her, as I was for my own husband. I conceived the idea that if in some way the two people whose lives had been upset by us could be brought together, then Frederick and I would be absolutely free and unburdened by the thought that we had achieved our happiness at the expense of others' misery. Frau Ritter was a good Hausfrau whose whole affection was for hearth and home. Dr. Koerwin was a man whose ideal woman she certainly represented; he appreciated domestic life in every way. If these two could, by great good fortune, take a liking to each other, our whole problem would be simply and painlessly solved, and I thought that later they might even join us in our Eden. If this solution had not seemed feasible to me I think that I should never have left my husband, because I believed strongly that happiness must never be bought at the price of innocent people's suffering. It was my plan that Frau Ritter would come into my husband's home and manage his household. This is an occupation which in Germany ladies go in for, and does not imply the social inferiority of the "housekeeper" in other countries. It was of course essential that this arrangement - which actually came to pass - be kept a secret, for the sensation mongering world, even in a large town like Berlin, is always eager to ferret out unusual situations and make a public scandal of them. But it seemed as though our secret would be kept. I had no difficulty in persuading my husband to make this attempt. However unwilling he might really have felt, he concealed this, doubtless realizing that the situation as it was was not only hopeless but full of danger - he still feared that things might arouse the notice of the neighbours. He even promised to consider the possibility of joining us later on the Galapagos, and as our plan matured, he placed two thousand marks at my disposal. It must not be thought that he did not even up to the last moment try to persuade me from what he thought a mad project. But when he saw that all his pleading was of no avail, he did a strange thing. He made me write a letter explaining why I had left him, and insisted that I write in praise of him and emphasize that we had had no quarrel, and that he had given me everything I had ever asked of him. It was with great fear and misgiving and with a feeling of painful suspense that I left for Dr. Ritter's home in Wollbach on a May day in 1929 to meet his wife and his mother. At the same time, he and I were to discuss our final preparations for our migration. I took along a large array of dresses but I did not wear them. It was Dr. Ritter's wish that I disguise myself as a man in order to escape identification. I was delighted at the success with which I passed for a youth, and both Frederick and I enjoyed my performance in this role. The coldness with which Frau Ritter first received me wore off, and soon she was almost as enthusiastic over our plans as I myself. We even prevailed upon her to fall in with my plan that she should take over my now abandoned household and try and like my husband. I was beside myself with joy as the last obstacle to our venture seemed to have been removed. The Ritter relatives raised great objections and implored Frederick to postpone his going, at least long enough to put his ideas into writing before he left. But he paid no attention to all of this. Frederick's mother was charming. It was quite natural that she should at first have been reluctant to have her son take me to see her, but no sooner had we met than she embraced me lovingly, and we both wept a little. I returned to Berlin, leaving Frederick still busy packing and making final preparations to leave his home in Wollbach for the distant Galapagos. It remained to me to break the inevitable news to my own parents. They were pained and shocked. My mother, however, with an understanding for which I shall always be more grateful than I can say, promised to use all her influence to console my husband and Frau Ritter, to keep in touch with them and help them both in every way. My father suffered terribly at the thought of losing me, perhaps forever. I was his favourite child, and his habitual depression always lifted while I was within reach to smile at him and say a cheering word. I knew that it was he who, in the end, would miss me most. It was curious that he had never liked Dr. Ritter, not even in the beginning when I had once wanted the new friend to meet my people and had taken him home with me. But Frederick thought a great deal of my father. As for the rest of the world, we rejoiced at leaving it behind. Civilization had no illusions for us. We had no interest in it, and the last thing we ever thought of was that it would ever take an interest in us. All that we both wanted was to be alone and to break free of the bonds of conventional life. We wanted to try and live a new way with neither models nor preconceived ideas to help - or rather hinder us. We wanted no advice and took none. Our work of discovery, whether it would turn out to be great or small, was to be all our own. It was my conviction that Dr. Ritter's experiment as a way of life would lack validity without a woman. But would I, as a woman, be able to rise to these occasions which I knew would come and be an acid test by which even two people who felt that they belonged irrevocably together, must prove the value of their relationship? For all the joy that filled me, I also felt a touch of fear. But I resolved that, come what might, I should be strong. And so the die was cast and we prepared to go forth to our experiment of more than Puritan self-denial, of repudiation of the flesh in a search for higher spiritual values. We had chosen a place where no one was, for we had learned that it is the contact with unlike natures that destroys the inner harmony of lives. We were to try and found an Eden not of ignorance but of knowledge. We did not know then that the world which we were leaving would pursue us there, to ruin what we made.