13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

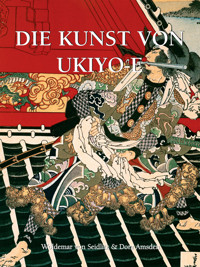

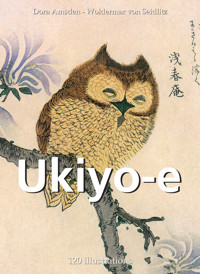

Ukiyo-e (‘pictures of the floating world’) is a branch of Japanese art which originated during the period of prosperity in Edo (1615-1868). Characteristic of this period, the prints are the collective work of an artist, an engraver, and a printer. Created on account of their low cost thanks to the progression of the technique, they represent daily life, women, actors of kabuki theatre, or even sumo wrestlers. Landscape would also later establish itself as a favourite subject. Moronobu, the founder, Shunsho, Utamaro, Hokusai, and even Hiroshige are the most widely-celebrated artists of the movement. In 1868, Japan opened up to the West. The masterful technique, the delicacy of the works, and their graphic precision immediately seduced the West and influenced greats such as the Impressionists, Van Gogh, and Klimt. This is known as the period of ‘Japonisme’. Through a thematic analysis, Woldemar von Seidlitz and Dora Amsden implicitly underline the immense influence which this movement had on the entire artistic scene of the West. These magnificent prints represent the evolution of the feminine ideal, the place of the Gods, and the importance accorded to landscape, and are also an invaluable witness to a society now long gone.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 77

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Dora Amsden - Woldemar von Seidlitz

UKIYO-E

Authors: Dora Amsden and Woldemar von Seidlitz

Translation: Marlena Metcalf

© 2023, Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© 2023, Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78160-949-1

Contents

Chronology

Theatre

Women

Gods

Humour

Polarity of Man and Woman

List of Illustrations

“All I have produced before the age of seventy is not worth taking into account. At seventy-three I have learned a little about the real structure of nature, of animals, plants, trees, birds, fishes and insects. In consequence when I am eighty, I shall have made still more progress. At ninety I shall penetrate the mystery of things; at one hundred I shall certainly have reached a marvelous stage; and when I am a hundred and ten, everything I do, be it a dot or a line, will be alive. I beg those who live as long as I to see if I do not keep my word.” Written at the age of seventy five by me, once Hokusai, today Gwakyo Rojin, the old man mad about drawing.

Beautiful Woman after her Bath and a Rooster, Okumura Masanobu, c. 1730

Benizuri-e, 31 x 44 cm. Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo.

Chronology

16th century:

Urbanisation in Japan gives rise to a merchant-artisan class that produces written work and paintings for public consumption, marking a divergence from the earlier court-based artistic tradition.

1603:

Beginning of the Edo Period.

1618:

Birth of Hishikawa Moronobu, who becomes influential in the development of woodblock printing techniques due to his practice of hand-colouring monochrome prints.

1688:

Beginning of the Genroku era, which lasts through 1704. Often called “the Golden Era of the Edo Period,” Genroku is characterised by economic development and a flourishing of the arts.

1752:

Birth of Torii Kiyonaga.

1753:

Birth of Kitagawa Utamaro.

1760:

Birth of Katsushika Hokusai.

1760s:

Invention of nishiki-e, translated literally as “brocade prints,” the process of layering colours on a print to create a richer effect.

1765:

The first publication of nishiki-e prints, created by Suzuki Harunobu.

1780s:

Torii Kiyonaga’s bijinga prints of courtesans and beautiful women are critically aclaimed, and many Ukiyo-e artists concentrate on this theme.

1797:

Birth of Utagawa Hiroshige.

1806:

Death of Utamaro.

1818:

First publication of the prints of Hiroshige.

1831:

Publication of Hokusai’s collection of prints, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.

1842:

Images depicting courtesans and kabuki actors are banned for a period due to the Tenpo social reforms.

1848:

Beginning of the Kaei era, during which foreign merchant ships from Europe and America arrived at Japan’s harbors in increasing numbers. The cultural effects of the Western influence are illustrated in the Ukiyo-e prints contemporary to this time.

1849:

Death of Hokusai.

1855:

The third of the Great Ansei earthquakes strikes Edo and kills 4,300.

1858:

Death of Hiroshige.

1868:

Official commencement of the Meiji Restoration, when the Imperial governement in Japan regains power and seizes the land of prominent people loyal to the previous shogunate. The abolishment of the samurai class and the blurring of societal lines due to reforms results in violent uprisings and protests. The art of Ukiyo-e falls into obscurity under the new social structure and the ensuing rise of industrialisation.

1880s:

The opening of Japan’s economy gives Western artists invaluable encounters with Eastern art, particularly the delicate and colourful woodblock prints, and Ukiyo-e experiences a revival in Europe.

1887:

Vincent Van Gogh paints imitations of the works of Hiroshige and Kesai Eisen. Van Gogh and other Western artists become avid collectors of Ukiyo-e prints.

20th century:

Revival of Ukiyo-e’s popularity in Japan. Artists such as Watanabe Shozaburo produce prints demonstrating significant Western influence.

Today:

Ukiyo-e is still regularly produced, and remains well-liked, particularly amongst Western tourists due to its treatment of traditional Japanese themes. The artform has been credited as being the inspiration for modern forms of popular Japanese art, such as manga and anime.

Lovers and Attendant, Hishikawa Moronobu, c. 1680

Ōban print, 29.7 x 35.3 cm. Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu

The Art of Ukiyo-e is a “spiritual rendering of the realism and naturalness of the daily life, intercourse with nature, and imaginings of a lively impressionable race in the full tide of a passionate craving for art.” This characterisation of Jarves forcibly sums up the motive of the masters of Ukiyo-e, the Popular School of Japanese Art, so poetically interpreted as “The Floating World”.

To the passionate pilgrim and devotee of nature and art who has visited the enchanted Orient, it is unnecessary to prepare the way for the proper understanding of Ukiyo-e. This joyous idealist trusts less to dogma than to impressions. “I know nothing of Art, but I know what I like,” is the language of sincerity, sincerity which does not take a stand upon creed or tradition, nor upon cut and dried principles and conventions. It is truly said that “they alone can pretend to fathom the depth of feeling and beauty in an alien art, who resolutely determine to scrutinise it from the point of view of an inhabitant of the place of its birth.”

To the born cosmopolite who assimilates alien ideas by instinct or the gauging power of his sub-conscious intelligence the feat is easy, but to the less intuitively gifted, it is necessary to serve a novitiate in order to appreciate “a wholly recalcitrant element like Japanese Art, which at once demands attention, and defies judgment upon accepted theories”. These sketches are not an individual expression, but an endeavour to give in condensed form, the opinions of those qualified by study and research to speak with authority upon the form of Japanese Art, which in its most concrete development, the Ukiyo-e print, is claiming the attention of the art world.

The development of colour printing is, however, only the objective symbol of Ukiyo-e, for, as our Western oracle Professor Fenollosa said: “The true history of Ukiyo-e, although including prints as one of its most fascinating diversions, is not a history of the technical art of printing, rather an aesthetic history of a peculiar kind of design.”

As the Popular School (Ukiyo-e) was the outcome of over a thousand years of growth, it is necessary to glance back along the centuries in order to understand and follow the processes of its development.

Though the origin of painting in Japan is shrouded in obscurity and veiled in tradition, there is no doubt that China and Korea were the direct sources from which the Japanese derived their art; while more indirectly, Japan was influenced by Persia and India, the sacred font of oriental art and of religion, which have always gone hand in hand.

Korean Acrobats on Horseback (fragment), Anonymous, style of Tomonobu, 1683

Monochrome woodblock print, 38 x 25.5 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Korean Acrobats on Horseback (fragment), Anonymous, style of Tomonobu, 1683

Monochrome woodblock print, 38 x 25.5 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Ichikawa Danjūrō I as Soga Gorō, Torii Kiyomasu I, 1697

Hand-coloured woodblock print, 54.7 x 32 cm. Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo

Kintoki and the Bear, Torii Kiyomasu I, c. 1700

Hand-coloured woodblock print, 55.2 x 32.1 cm. Honolulu Academy of Arts, gift of James A. Michener, Honolulu

Tiger and Bamboo, Work attributed to either Shigenaga Nishimura or Okumura Masanobu, c. 1725

Woodblock print with gold powder, 33.5 x 15.4 cm. Private collection

Beautiful Woman after her Bath and a Rooster, Okumura Masanobu, c. 1730

Benizuri-e, 31 x 44 cm. Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo

In China, the Ming dynasty gave birth to an original style, which for centuries dominated the art of Japan; the sweeping calligraphic strokes of Hokusai mark the sway of hereditary influence, and his wood-cutters, trained to follow the graceful, fluent lines of his purely Japanese work, were staggered by his sudden flights into angular realism.

The Chinese and Buddhist schools of art dated from the sixth century, and in Japan the Emperor Heizei founded an imperial academy in 808. This academy, and the school of Yamato-e (paintings derived from ancient Japanese art, as opposed to the Chinese art influence), founded by Fujiwara Motomitsu in the eleventh century, led up to the celebrated school of Tosa, which with Kanō, its impressive, aristocratic rival, held undisputed supremacy for centuries, until challenged by plebeian Ukiyo-e, the school of the common people of Japan.