3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: mikrotext

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

For the second time in history, masks have become the symbol of a global pandemic. The facial front lines differ in shape and size and are fashioned to the users’ desires, reaching from African prints to floral patterns. But are masks solely ‘germ-shields’ or ‘dirt-traps’ as referred to a century ago? What does the choice of fabric actually reveal about its wearer? And in which way are differences ‘un_masked’? Authors, academics and activists from different backgrounds share their ideas on the historical, political, religious, racial and cultural, as well as on the intersectional dimension of masks. Similar to W.E.B. Du Bois metaphor of ‘the veil’, which solely exists in people’s minds, masks can be seen as the physical manifestation of the inner and outer world, the speakable and the unspoken. With texts by Logan February, Precious Colette Kemigisha, Olumide Popoola, Djamila Ribeiro, Jeferson Tenório und Sheree Renée Thomas. A publication of the Literary Colloquium Berlin with the kind support of the Federal Foreign Office. Natasha A. Kelly has a PhD in Communication Studies and Sociology with a research focus on Black German Studies. Her award-winning and internationally acclaimed documentary "Millis Awakening" was commissioned by the 10th Berlin Biennale in 2018. Based on her book "Sisters & Souls" (2015) she has been directing the sequential theater performance "M(a)y Sister" since 2016. Her dissertation "Afroculture. The Space between Yesterday and Tomorrow" (2016) was staged in three countries and three languages in 2019/20. Her latest publication "The Comet – Afrofuturism 2.0" (2020) is a documentary of the Black speculative arts symposium which she curated at the HAU Hebbel am Ufer Theater in Berlin. http://www.natashaakelly.com

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 105

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Summary

For the second time in history, masks have become the symbol of a global pandemic. The facial front lines differ in shape and size and are fashioned to the users’ desires, reaching from African prints to floral patterns. But are masks solely ‘germ-shields’ or ‘dirt-traps’ as referred to a century ago? What does the choice of fabric actually reveal about its wearer? And in which way are differences ‘un_masked’?

Authors, academics and activists from different backgrounds share their ideas on the historical, political, religious, racial and cultural, as well as on the intersectional dimension of masks. Similar to W.E.B. Du Bois metaphor of ‘the veil’, which solely exists in people’s minds, masks can be seen as the physical manifestation of the inner and outer world, the speakable and the unspoken.

Edited by Natasha A. Kelly

Un_Masking Difference

Literary Voices from Behind the Mask

With texts by Logan February, Precious Colette Kemishiga, Olumide Popoola, Djamila Ribeiro, Jeferson Tenório, Sheree Renée Thomas

a mikrotext

Created with Booktype

Guest Editor: Lara Gross

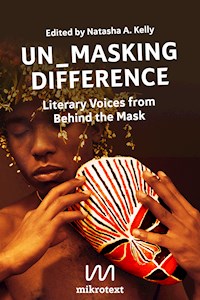

Cover Image: Adebeyi 1989, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Courtesy Autograph London

Cover: Inga Israel

Cover Typeface: PTL Attention, Viktor Nübel

www.mikrotext.de – [email protected]

ISBN 978-3-948631-11-6

A publication of the Literary Colloquium Berlin with the kind support of the German Federal Foreign Office.

All rights reserved.

© 2020 mikrotext, Berlin / the authors

Un_Masking Difference

Summary

Imprint

Title Page

Editor's Note

Test Instructions. By Jeferson Tenório

Masks and Candomblé. By Djamila Ribeiro

BOTANICA. By Sheree Renée Thomas

Mask of the Nautilus. By Sheree Renée Thomas

The Many Layers. By Precious Colette Kemigisha

A Good Person. By Logan February

Contractions. By Olumide Popoola

Bodies of Experience. By Logan February & Olumide Popoola

The Editor

The Authors

About mikrotext

Sample: Bino Byansi Byakuleka

Sample: Dear Discrimination

Quote from "The Souls of Black Folk"

Edited by Natasha A. Kelly

Un_Masking Difference

Literary Voices from Behind the Mask

With texts by Logan February, Precious Colette Kemigisha, Olumide Popoola, Djamila Ribeiro, Jeferson Tenório and Sheree Renée Thomas

Editor's Note

For the second time in history, masks have become the multifaceted symbol of a global pandemic. The facial front lines differ in shape and size and are fashioned to the users’ desires, reaching from African prints to floral patterns. But are masks solely ‘germ-shields’ or ‘dirt-traps’ as referred to a century ago? What does the choice of fabric actually reveal about its wearer? And under which circumstances do masks enable people to breathe or do they lead to suffocation, as argued by the New Right?

Originating from the last words of Eric Garner, an unarmed Black man killed by the police in 2014, and associated with a number of other homicides by the police, including that of George Floyd in May 2020, the slogan "I can't breathe" has become the catchphrase used by Black people and their allies in protests against police brutality and systemic racism all over the world. However, the ongoing global pandemic gives reason to re-examine these words and ask in which way the inability to breathe is connoted with masks and at the same time entangled with structural racism? In this sense, masks have gained new relevance with old significance.

As Corona unfolded, we learnt that the lungs are affected by the virus, which eventually leads to the loss of breathing and death by suffocation. However, the right-wing “Anti-Mask-League” made its centennial return by demonstrating against the health restriction of wearing masks in public. Storming the German Reichstag and revealing their racist ideology in August 2020, conspiracy theorists, neo-Nazis, as well as ordinary people refused to wear a mask, not only spreading the virus rapidly but also distracting media attention from the Black Lives Matter Movement to their so-called “Hygiene Demonstrations”.

In this sense, not only the virus, but also masks have served to expose racial inequities that have existed worldwide for centuries. Similar to W.E.B. Du Bois’ metaphor of ‘the veil’, which solely exists in people’s minds, masks can be seen as the physical manifestation of power structures, which have made the ability to breathe become visible. They at once represent life and death, speech and silence, culture and nature etc., depending on where one is located. This understanding is reflected in the underscore in the verb ‘to un_mask’ in the title of this publication, which stands for the many gaps, cracks, and in-between spaces, as well as actions and processes that create and cement social, racial, gender and class differences. In this sense the mask becomes a physical symbol of ‘the veil’ stressed by the underscore that makes ‘masking’ and ‘unmasking’ simultaneous, yet opposing actions.

In Ancient Africa, for example, masks were designed with human or animal characteristics or a mixture of both. In masking ceremonies spiritual or religious significance was celebrated accordingly. Stolen from their creators during colonialism, the spiritual and/or religious aspects of these masks were undermined as they were reduced to artifacts and hung in European museums. In this context, the cultural meaning of masks is erased, and Eurocentric ideas are imposed. At the same time, we are provoked to ask what is actually being ‘un_masked’ by whom and why. Engaging in the masking traditions of their enslaved ancestors, Trinidadians modelled the Caribbean Carnival, to celebrate the resistance to and rebellion against colonialism. However, the French settlers in Trinidad would engage in masquerade balls, where some would dress up as enslaved Africans and engage in scandalous behaviour – in this case, the opposite meaning of ‘un_masking’ is evident. During enslavement so-called ‘iron muzzles’ were used to torture and silence enslaved Africans when accused by their masters of insubordination, or of eating more than their ration of food. In his autobiography former slave, Olaudah Equiano described his first encounter with such a device in the mid-1700s:

“I had seen a black woman slave as I came through the house, who was cooking the dinner, and the poor creature was cruelly loaded with various kinds of iron machines; she had one particularly on her head, which locked her mouth so fast that she could scarcely speak, and could not eat or drink.”1

In this regard, masks have for a long time been a symbol of racial inequality and a means to discuss race relations and identity. The Afro-French psychiatrist, politician, writer and post-colonial thinker Frantz Fanon, for example, used the metaphor of the ‘white mask’ to describe the manifestation of the social psychosis caused in Black people by their racist domination and submission. He wrote that anti-colonial revolts occurred when it became “impossible to breathe”.2 Since the Summer of 2020 Fanon’s words can (again) be taken literally. Dominating television, social media and the internet, the video of George Floyd calling for his mother and gasping for his last breath of air before he died on camera, put the global Black community in stranglehold. But understanding breathing as a metaphor for social survival, it also becomes possible to interpret “un_masking”, thinking with postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha (1994), as a sociolinguistic concept that opens a ‘Third Space’3, where the oppressed are able to plot strategies for their liberation and freedom.

In Autumn of 2020 authors, academics and activists from Africa and her diaspora were invited to a virtual residency by the Literarisches Colloquium Berlin to exchange and document their ideas on the historical, political, religious, racial and cultural, as well as on the intersectional dimension of “un_masking”. Working through the political moment, the following texts are the result of a shared healing and learning experience that offered space to write, think and “breathe” against the grain and digest the violence and trauma Black bodies continue to face in the 21st century. It was my honour to curate this literary exchange and edit this volume, which is at once documentation and archive.

Natasha A. Kelly

Berlin, December 2020

Captured from Africa at the age of 11, Olaudah Equiano was sold into slavery, later acquired his freedom, and wrote his widely-read autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African in 1789.

In 1952 Frantz Fanon wrote his ground-breaking book Black Skin, White Masks, in which he shares his own experiences while presenting a historical critique of the effects of racism and colonisation.

Source: Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture. London: Routledge

Test Instructions. By Jeferson Tenório

The way she said it made me know what I have must looked like other mornings: it made me know what I looked like.

—James Baldwin, If Beale Street Could Talk

1. colour: positive or negative

I am a black man. Since I was born, I’ve been told this. At times I think that my only path in life is not to be a black man any longer. Perhaps I’m tired of having a colour. My father died ten years ago and was a white man. He was a good man, and even if he was always complaining about things, grumbling about how we were poor, how there was no money left for anything, I never saw him complain about being white. I also never saw my mother complain about being black. Perhaps she had no time to spare for that. But I knew how much the colour weighed her down.

As I grew up, I started to understand that white people don’t get tired of having a colour. I thought about it once while waiting for my girlfriend Jessica to come out of the pharmacy. We were out for a pregnancy test when I saw a white couple entering the pharmacy looking like they didn’t have a care in the world. I kept looking, wondering what life was like for them. Perhaps they never thought about the violence of being white. When they saw me staring, I looked away. They bought some aspirin and left. Jessica and I left right after. We went to my house. It was cold in Porto Alegre, a humid day like they always are in wintertime.

We can’t have this baby, Ka.

As she said this, Jessica, on the way home, looked at me, sad and guilty. I never liked it when she looked at me like that. Those eyes made me weak, I always thought we were too young to be sad and worried like that.

Hey, don’t be upset just yet, let’s take the test first, I said.

Then I hugged her all the way home. I shared an apartment with my college friend, Guto. I was halfway through an architecture B.A. Jessica was starting journalism. The neighborhood I lived in was predominantly white. It was close to school.

When we arrived, we took our masks off, washed our hands. Guto was not there. He had gone to his girlfriend’s. Jessica went straight to the bathroom to take the test. I stayed by the door and lit a cigarette.

Ka, don’t fucking smoke in here, Guto is gonna complain, Jessica said from the bathroom.

Fuck Guto, I said back. Then I inhaled twice and put out the cigarette.

Jessica left the bathroom holding the stick, looking apprehensively at the piece of plastic. Jessica read every instruction out loud and then summed them up:

We have to wait a few minutes until a colour for the negative or positive result appears.

Jessica was nervous, I thought about reassuring her by saying everything would be OK if she was pregnant. She looked at me, astonished.

No, Ka, it would not be ok, because I won’t have this baby. If this fucking test is positive, I’ll start looking for an abortion clinic right now. I'm not going to ruin my life and the life of another black kid in this fucked-up world.

Easy, Jessica, I only meant I’m here for you.

Jessica kept silent for a while, then apologised and said she was scared.

We said nothing until the results came up.

2. of peaceful people

I am a black man, and I am not dangerous.

I should have this written on my forehead.

We went to make dinner. Jessica and I liked to cook. Transforming raw things. Getting raw things and changing them up. Doing this was good for us.

I don’t know, Ka, pharmacy tests might be wrong, she said as she cleaned a lettuce leaf.

Yes, but I heard it’s kinda rare. These tests usually are right. On Monday we can go to the doctor and get a blood test, I said.

Maybe that’s better. My period is never late like this. You know I work like a clock. Two weeks is too much. I know the test was negative, but it did not ease my mind.

Our silence allowed us to listen to the news about the pandemic on TV.