18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

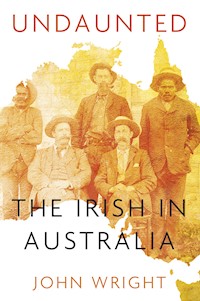

Undaunted is a collection of true stories about Irish men and women who travelled to Australia in search of a better life and battled against the odds in a remote and harsh world. From 1788 when the first convict ships landed to the mid-20th century, these true stories about settlers, convicts and their descendants highlight the best and worst of human behaviour in the kinds of dilemma that faced newcomers. This book tells the story of the Irish contribution to this struggle.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Pearce the Peckish

2 Chasing Brady

3 Strictly Cash

4 Finding the Castaway

5 The Butcher

6 Search Party to Nowhere

7 Edward Evans’ Secret

8 Waiting for Burke and Wills

9 Captain Moonlite

10 Australia’s First Whodunnit

11 The Lost VC

12 The Loch Ard Disaster

13 The Day the Constable Came

14 The Last Bushranger

15 The Dangerous Persuasive Woman

16 Freud and the Outback Postie

17 ‘Killarney Kate’

18 The Original All Black

19 Midwife Mary

20 Lady of the Outback

21 The Sentimental Bloke

22 Lord of the Ring

23 The Deserter’s VC

24 Very Alicia Mary

25 Madge, the Cop with no Badge

26 Runaway Nun

27 The Sydney Harbour Horseman

28 Death on Alligator Creek

29 The Missing Plane

Copyright

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the people and organisations that supplied pictures or gave permission for their use. Thanks also to the following for their help: (Loch Ard Disaster) Eva Carmichael’s great-grandson Richard Townshend; Colonel John Townsend who, like Eva Carmichael’s future husband Thomas Townshend, is a descendant of Colonel Richard Townesend of Castletownshend, County Cork; and Loch Ard researcher and tour guide Len Sherrott; (Midwife Mary) Noeline Kyle, great-granddaughter of Mary ‘Nurse Kirk’ Kirkpatrick and author of Memories and Dreams; (Death on Alligator Creek) Jennnifer Pomfrett, editor of The Daily Mercury, Mackay, and the following people in Queensland I spoke to in 2003 – Jannie Weymouth, Calen state school teacher/librarian; Chris Williams, wife of the Tuckett girls’ teacher Richard Williams; Jean Turvey, secretary of the Mackay Family History Society; Ken Manning, local historian and son of former owner of The Daily Mercury; Dr Mark Read, Townsville government scientist in charge of crocodile research; Georgina Carroll and her mother Theresa Doolan who both knew Grace Tuckett; Jim McAlonan, publican of the Leichhardt Hotel, Mackay; Emmett O’Brien, the marksman’s great-grandson; (Missing Plane) Bernard O’Reilly’s nephew Peter and Catherine O’Reilly interviewed in 2002 and Shane O’Reilly, Managing Director of O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat, Queensland.

Introduction

Any teenager would be caught off-guard if their parents suggested moving to the other side of the world. As I suspected at the time, mine had already made their minds up, and so, in April 1965, I found myself leaving the lanes and green fields of England’s West Country with my family on a ship bound for Australia’s island state of Tasmania. We were ‘£10 Poms’.

Travelling conditions on our four-week trip on the P&O Himalaya – deck quoits, swimming pool and non-stop catering – were certainly better than they would have been during the first recruiting period in Australia’s history. Then, convicts and settlers were tossed about in rickety sailing ships on voyages that could last as long as six months.

As well as Irish settlers from all walks of life, more than 25,000 convicts from Ireland were part of Australia’s first wave of European arrivals; men, women and children convicted largely of petty crimes – stealing to put food on the table in a notoriously unfair world being one common offence. The first of these convicts left one another April, almost two centuries ago, in 1791 (transportation ending as a punishment in Ireland in 1853). They, together with 136,000 convicts from Britain and all the settlers and officials, comprised the uneasy mix of humanity that was setting out to build a new nation from scratch.

When we arrived, slightly dazed, at the gates of Devonport High School in northern Tasmania, we were almost mobbed by other kids asking us if we had seen The Beatles, and it was impossible not to be instantly charmed by this new place. Those children, descendants of those earlier settlers, blended effortlessly with the likes of us who were less sure of precisely what lay ahead.

The chance for adventure was everywhere; even today, its potential for mystery and danger is always apparent, whether it is bushfires, deserts, remote bushwalking or sharks. But in Australia there are also reminders of other people’s stories: the struggles of far braver souls who immediately had to cut down trees to make their houses and clear enough bushland to farm and be self-sufficient. Or face starvation. Often you can see signs of these earlier lives when you are driving around: an old signpost to a distant bluff, a dusty ghost town, an abandoned hut. Who lived in these places, and how on earth did they make a living?

Shortly after arriving in Tasmania, we got a glimpse of a recent era that was ending; wandering with friends near the Devonport Showground one quiet Sunday afternoon, we opened the door of a corrugatediron shed to find a riotous dance in full swing. The place was bursting with people jiving – to us an exciting if old-fashioned dance – and I remember two men in particular dancing together so athletically that they would fling each other between their legs.

It was only about a year later when the Australian public witnessed the disappearance of another era – in fact, a whole culture – as the TV news showed the last few near-naked aborigines that existed in the wild being led out of the outback to live in what was considered to be Australia’s more civilised world, with houses, piped water, clothing and food from shops.

This book is about how everything started in Australia, when the Irish joined others – voluntarily and otherwise – in jostling for space in its unfamiliar landscape, with its endless bushland of eucalyptus, acacias, dense scrub and dry grass, and its hot climate and barren ground that would make settlement so hard, where so many families had no choice but to try to make a fresh start in forging a productive future.

Covering just over a century, from the 1820s (thirty years after the very first ships sailed into Botany Bay in New South Wales in 1788) to the 1930s (by which time technology had well and truly arrived), these stories represent the human tensions that affected people in those early days, not just between each other, but also in this immigrant society’s clumsy efforts to communicate with aborigines, whose very presence and way of roaming freely were seen by some as an obstruction to their colonisation plans.

The evolved wisdom for survival of the indigenous people was rarely learnt from, and explorers, at their peril, frequently brushed past aborigines in the outback, thinking that they were the ones who had all the answers. It was also perhaps inevitable that these newcomers, when faced with indigenous men with spears, would assume that they themselves were the prey, rather than the kangaroos and other animals they hunted for food. The presence of an ancient culture in Australia caused a host of genuine misunderstandings and more cynical clashes, sometimes instigated by the more forceful colonisers who saw this new world as their own and were bent on bringing this less powerful group to heel.

Still, even without the conflict with the aborigines, life was hard for those who had come from other countries, even if they turned up in the ‘get-rich-quick’ atmosphere of the gold rush in 1850. The competitiveness and rough life meant that they needed all their wits to survive in a place with so many unpredictable dangers, the dilemma made worse by jealousy and rivalry when one group was seen as having it easier than another. This contrast in fortunes can be witnessed today, when elegant Georgian-style sandstone houses set in beautiful city gardens are as much part of the scene as the equally exciting, once thriving, now bypassed country townships you have to leave the highway to find.

If many of these Australian stories are about Irish men, some of them show women who had their own ideas about who had the right to share in the spoils of discovery and the fun of being free. Together, these stories are a snapshot of what some of the spirited individuals and families from Ireland got up to in the bleakest of settings, at a time in history when the odds were stacked against them and failure sometimes seemed inevitable.

Pearce the Peckish

They called him ‘the man-eater of Macquarie Harbour’. One American book said he lured fellow convicts to escape so that he could get them to ‘his lair in the woods’, where he would eat them and maintain a constant supply of fresh victims.

But who was this apparent monster? He was Irishman Alexander Pearce. Born in 1790, he was sentenced to transportation at the County Armagh Assizes for stealing six pairs of shoes, and left Ireland on 3 October 1820 on the ship Castle Forbes. Official records state that he came from County Monaghan, but he would later tell a gaoler that he was from County Fermanagh.

In 1850, the Cornwall Chronicle in Van Diemen’s Land (later Tasmania) claimed that the state’s Pieman River was named after Pearce and that he used to be a pie man in Hobart Town (later Hobart); the Hobart Town Courier in 1854 suggested that Pearce was sent to Macquarie Harbour for ‘selling “unwholesome meat” made into pies’.

The story about him had many embellishments, but was any of it true? The answer is yes. Alexander – ‘Have a Break, Have a Forearm’ – Pearce became a bushranger when, in 1822, he escaped with seven other convicts from a high-security penal station on Sarah Island in Macquarie Harbour. Situated on Tasmania’s isolated west coast, if inmates did escape, the expectation was that they would never be seen again.

With Pearce were Alexander Dalton, Thomas Bodenham, William Kennerly, Matthew Travers, Edward Brown, Robert Greenhill and John Mather. Their progress would have been slow, as they made their way up and down mountains, through rainforests with misty rain falling the whole time, forcing their way through dense scrub and across wild rivers. They would have been lost almost immediately, the weather here being famous for constantly changing without notice. They had escaped into some of the harshest, most impenetrable country in the world – almost half the size of Ireland. They carried with them only a few days’ worth of food they had stolen. Aborigines knew how to survive here but these men did not. They were on their own.

It was Alexander Pearce who acquired all the infamy; not because he escaped successfully but because in the end he was the one who, after several months in the bush with all the others, walked out alone. When Pearce told the police what he had done to stay alive, they did not believe him. They assumed he was lying to protect the others who were still at large, and instead of hanging him they sent him back to Macquarie Harbour.

In short, their meagre food supplies ran out after a week. They tried boiling the leaves of certain trees to extract the juice. It made them sick. They started eating ‘wild berries and their kangaroo jackets, which they roasted,’ wrote James Bonwick in The Bushrangers. But it did not fill them for long. Dan Sprod, in his detailed account, Alexander Pearce of Macquarie Harbour, quoted Pearce as saying, ‘Kennerly said he was so hungry, he could eat a piece of a man.’ Another of the men, Robert Greenhill, had introduced the subject, saying, ‘he had seen the like done before, and that it tasted very like pork’.

Rainforest in western Tasmania: the kind of landscape in which Pearce became lost. (Photograph by Siegfried Manietta, Senior Lecturer, Photography, Griffith University, Queensland College of Art, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia)

The survival game they seemed to play was along the lines of ‘staying awake the longest’. From Pearce’s own account, now residing in the National Library of Australia in Canberra, the eight men decided to cast lots and Thomas Bodenham lost. When he slept, Greenhill killed him by giving him ‘a severe blow in the head … then taking his knife began to cut the body into pieces’. They put the body on the fire to cook. When it was time to head off, so to speak, they took the carcass with them to keep them going later.

John Mather was next. He actually wrestled the axe away from Greenhill and encouraged the others to agree not to let him have it anymore. But they lied. Then it was the other Irishman Matthew Travers’ turn. He had been bitten by a snake and was slowing them down. His dreaming of County Kildare was over. ‘Each of us took as much of the body of Travers as we could carry,’ said Pearce.

One day they heard voices: it was a big group of aborigines. But instead of befriending them in the hope that they might show them a way out, they scared them away and settled for eating the kangaroo flesh, snakes and possums they left behind.

Then Greenhill tried to kill Pearce in his sleep. Pearce, however, was only pretending to sleep and later killed Greenhill with the axe when he nodded off. ‘I cut off part of his thigh and arms, which I took with me … until I had ate it all,’ Sprod later quoted Pearce as saying in his statement. And then there were four. Alexander Dalton disappeared, and William Kennerly did not want to be the next victim so he ran away too. Kennerly did return to ‘civilisation’, where he finished the last bit of John Mather he had with him but died of exhaustion.

Alexander Pearce finally got back – the only one still alive. Even for those who did believe what he had done, there was insufficient proof of murder. Later that year, Alexander Pearce again escaped from Macquarie Harbour, this time with another convict, Thomas Cox, who actually begged to go with him. Clearly, Cox had not listened to the gossip or believed it if he had, and he would never know that the Hobart Town Gazette would later report on Pearce’s trial and describe him as ‘the being who had banqueted on [Cox’s] human flesh’.

Alexander Pearce was executed for the murder of a man named Cox at Macquarie Harbour. (In Thomas Bock’s Sketches of Tasmanian Bushrangers, c. 1823–1843, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (NSW). Call no. DL PX 5 f.26, Digital order no. a933010)

Had they only been cannibals, as Pearce would assert, to stay alive? One week into this second escape Pearce gave himself up, despite still having some of their stolen food supplies with him. Even this time there would not have been any evidence to hang him – had it not been for the bits of Thomas Cox they found in his pockets.

Chasing Brady

Poor old police magistrates like Newry-born William Gunn, who chased after bushrangers during Tasmania’s convict days, rarely got any praise. Certainly not from the public, at least, if the man they were after was someone like Matthew Brady, the man they called ‘the gentleman bushranger’.

More often than not, bushrangers were simply men transported to Australia for committing fairly minor crimes – Brady had stolen butter, bacon, sugar, rice and a basket (perhaps in which to carry them) – who tired of being cooped up in gaol or in service and headed for the hills (of which, luckily for them, there are plenty in Tasmania). Then, in order to stay alive, they sought food and supplies from homesteaders they came across. Brady’s popularity meant that he rarely had to insist.

He was well known for never hurting anyone unless in self-defence; he imposed the same strict rules on his gang members and once kicked his offsider, McCabe, out of his gang when he threatened to hurt a woman. Born in Manchester in 1799 of Irish parents, he was twenty-one when he was transported. His persistent efforts to escape from prison were not appreciated, and in four years he was given 350 lashes for trying.

Like Pearce, Brady was sent to Sarah Island and in June 1824 he succeeded in escaping. He and fourteen others stole a boat and headed south in rough seas around the south of Tasmania, towards the familiar area of Hobart Town on the Derwent River. A number of stunts made the general public warm to him and allowed him to remain free. When Governor Arthur put ‘Wanted’ posters up for the gang, Brady put up similar posters of his own saying, ‘It has caused Matthew Brady much concern that such a person known as George Arthur is at large. Twenty gallons of rum will be given to any person that can deliver his person to me.’

Sketch of James McCabe, Matthew Brady and Patrick Bryant. (In Thomas Bock’s Sketches of Tasmanian Bushrangers, c. 1823–1843, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW. Call no. DL PX 5 f.8, Digital order no. a933010)

The public loved it, and for some time ‘bushranger mania’ seemed to grip the community. With soldiers everywhere out looking for him, one day Brady went into Hobart and boarded the mail coach to Launceston, having arranged with gang members that they would rob it at a certain spot along the road. They also once captured a whole township, Sorell, just east of Hobart. They robbed twelve members of the Hobart gentry who were having dinner there and put them in the lock-up, together with some soldiers who had just returned from looking for them.

How could William Gunn compete with that? Born on 6 September 1800, the eldest child of Lieutenant William Gunn and his wife Margaret (née Wilson), William was twenty-two when he sailed for New South Wales, where he planned to join the army. Instead, he was waylaid in Hobart Town, where Lieutenant-Governor William Sorell talked him into staying in Van Diemen’s Land, granting him 400 acres (162 hectares) near Sorell, where, at twenty-nine, he would marry Frances Arndell and begin their family of nine children.

Gunn spent three years in command of soldiers, chasing after bushrangers like Brady (who was also in his twenties), and in November 1825 he was badly wounded by a shot from a Brady gang member which led to his arm being amputated. Instead of getting his man, he was forced to settle for a colonial pension of £70 and a public subscription of £341 for his ‘patriotic exertions’.

Now away from the chase, he was made superintendent of the Prisoners’ Barracks in Hobart and in 1832 ran the Male House of Correction, rising in rank in the Convict Department in Launceston, northern Tasmania, until his retirement, which heralded the end of transportation. Coming from the right side of the tracks, Gunn was widely respected for being brave and generous, giving both land and money to the Anglican and Congregational churches at Broadmarsh, just north of Hobart.

William Gunn, January 1868. (AUTAS001125645358 publisher: Launceston, possibly Cawston. Source: Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)

William Gunn died on 10 June 1868. One historian, K.L. Read, ended a biography of him with a genteel observation, hardly born of knowing or bothering to recognise the desperation and rough riding ‘the hired Gunn’ once knew, by saying that his Launceston home, Glen Dhu, ‘was noted for its lawns and gardens; the rose garden was claimed to be the best in Australia’.

Matthew Brady would be talked about in a different way. The more popular Brady became the more people wanted to join his gang and the harder it became to control them. At one time there were twenty-five in his gang, and a hundred others trying to emulate him. Thomas Jeffries, an escaped convict who had been a painter and decorator in Bristol, England, joined the gang but was immediately forced to leave when they found out how violent he was.

While Brady had escaped from Macquarie Harbour rather sensibly by sea, Jeffries had attempted it the Alexander Pearce way, and, likewise, had managed to stay alive while on the run by eating one of his friends. Heading across mountainous country and dense rainforests with two others, Russell and Hopkins, Jeffries suggested that they tossed to see which of them should be eaten by the others. Russell lost and went to sleep, thinking it had been a joke. ‘Jeffries shot Russell in the head,’ wrote Allan Nixon in 100 Australian Bushrangers, ‘cut up the corpse and lived on it for four days.’

Eventually he reached the settled areas of the state’s north, where his vicious spree continued, shocking even other bushrangers. He called himself ‘Captain Jeffries’ and wore a kangaroo skin cap, long black coat and red vest. On Christmas Day in 1825, he held up two farm workers; one ran away, but Jeffries wounded the other one, before catching up with him and shooting him again.

He and Hopkins raided the homestead of a landowner called Mr Tibbs, and when he complained they shot him and his stockman. He then ‘forced Mrs Tibbs, who had a five-month old baby at her breast, to accompany them into the bush,’ wrote Nixon. ‘When she found difficulty in keeping up with them, Jeffries grabbed the baby from her arms and smashed its head against a tree trunk.’ Soon afterwards he shot a Constable Baker without warning.

In the end, it was a bounty hunter called John Batman who tracked Jeffries down. So quickly had the news spread about what he had done that Launceston residents flocked to see him punished and tried to pull him from the cart on his way to prison. Brady had been caught too, ‘given up’ by a spy who had tricked his way into the gang, and was now on trial for the murder of the informer, Thomas Kenton. Jeffries had informed on Brady as well, and they were tried together.

When Brady’s death sentence was passed, women cried in the court, but Governor Arthur ignored all the pleas for mercy. Matthew Brady was hanged on 4 May 1826, at the age of twenty-seven. That he was executed with a man like Thomas Jeffries did not please him one bit.

Strictly Cash

Most bushrangers in Australia ended their days in a hail of bullets, but not one wily County Wexford man. Martin Cash lived until he was sixty-seven, a ripe old age for an outlaw on the run.

Cash had been a passionate man from the start. Born in 1810 in Enniscorthy, he became so used to seeing his father squandering his inheritance that he was soon no stranger to pubs and racetracks himself. He was transported to New South Wales at the age of nineteen for the vague crime of ‘housebreaking’. He had actually shot and wounded a man called Jessop for embracing his girlfriend, firing at him through a window. Not to be outdone, his father was shot in a duel that same night, perhaps by Jessop’s father?

At first Cash did not fit the mould of a re-offending convict. In fact, he did the farm work he had been given on the Australian mainland and quietly served out his seven years. Then ‘one day he was innocently branding some cattle for a friend when two men rode up and watched him at work for a while,’ wrote Geoff Hocking in Bail Up! His friend informed him that the cattle were stolen. The last thing he wanted was trouble (of the legal kind, anyway), so he sailed to Tasmania in 1837 with his girlfriend Bessie Clifford, ‘whom he’d persuaded to leave her husband’. Cash was twenty-seven and a model citizen. Another year went past; still no trouble.

Martin Cash. (Series: ‘Miscellaneous Collection of Photographs, 1860–1992’ (PH30–1–672). Source: Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)

But trouble did find him. He was falsely accused of theft twice and decided to retaliate, once, wrote Hocking, beating ‘the arresting officer so badly that, from then on, he was a marked man’. Thus ended his peaceful life. Sentenced to yet another seven years working on road gangs, he escaped two days after he started.

When recaptured, Cash escaped from a chain gang by smashing his chains with a rock and climbing a compound wall. And so it went on. Stealing clothes to look respectable so that he could find Bessie again, Cash evaded would-be informers as he went, such as one interfering schoolteacher in Campbell Town in Tasmania’s Midlands, who got knocked down after firing a shotgun at him.

They spent a year safe on the Huon River, south of Hobart, where Cash worked as a boat-builder while saving up to catch a ship to Melbourne. But one day, on a trip into town, he was recognised. This time he was sent to the infamous Port Arthur gaol in Tasmania’s southeast, where only the most hardened offenders were sent and from where no one was known to escape. The sea around the peninsula on which it was built was believed to be shark infested, and Eaglehawk Neck, the narrow stretch of land joining it to Tasmania’s mainland, had guard dogs chained up across it, should anyone dare to pass.

Perhaps it was the assumption that Cash would not dare try it that allowed him to catch them napping. His moment came unexpectedly: he threw his work-gang overseer into the sea for shouting at him, and ‘while the other convicts and soldiers were occupying with fishing him out,’ said Robert Coupe in Australian Bushrangers, Cash ran off. Diving into the sea, he made it across, only to be dragged back five days later. Extraordinarily, he even talked his way out of a flogging. By then he was the local hero, having made it across, and so two others asked to go with him the next time he tried.

Cleverly, it was on Boxing Day 1842, when the guards were preoccupied with celebrating, that Cash – this time with Irish burglar Lawrence Kavanagh, from the town of Waterford, and London burglar George Jones – escaped from a quarry. They swam with their clothes held above their heads, but waves swept away what they were hoping to wear. Finally, they arrived safely on the other side, past the dogs, stark naked and laughing. The Cash gang was born. Using bluff for most of their robberies, they stole for food and ‘made a pact,’ wrote Coupe, ‘that they would not resort to ruffianism’.

Reward notice for Martin Cash, 19 January 1843. (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, Call no. Drawer item 444, Digital order no. a018001)

For twenty months they remained at large, and one night they held up the Woolpack Inn near New Norfolk, despite the presence of constables. After a shootout, Cash ran back inside to see his two mates hiding behind the bar. He was never a good judge of character. Unmoved, he grabbed a barrel of rum and they managed to escape together, riding off to the top of a nearby hill. Here, with views all around, they built a fort using three logs in a triangle, the kind of which Enid Blyton’s Famous Five might have been proud.

From here, he sent a message to Bessie. She joined them, but soon returned to Hobart when they heard that the 51st King’s Own Light Infantry were approaching. Bessie was then arrested, the authorities hoping that somehow she could be used to lure Cash back into town. In an unexpected move, the cheeky gang turned up at the home of a startled family, where George Jones wrote a letter to the governor, Sir John Franklin, saying that if he did not release Bessie ‘we will in the first instance visit Government House, and beginning with Sir John, administer a wholesome lesson in the shape of a sound flogging’. Amazingly, Bessie was freed.

You can imagine all the shutters in Hobart Town closing the day Martin Cash rode into town after hearing that she had been seen with another man. Was the news that she was free a trap? In yet another shootout with police, Cash, who was a formidable runner, escaped with all guns blazing, but not without fatally shooting a constable.

This time, ‘the Wexford Houdini’ managed to elude the death sentence, just one day before it was carried out, after a host of wellwishers, which, extraordinarily, included soldiers and other officials, arrived to give him support. Instead, he was sent to the penal settlement of Norfolk Island, in the Pacific Ocean between Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. There he kept his head down and did his time, while Kavanagh and Jones met the fate that once awaited him.

Martin Cash’s house, Montrose Street, Glenorchy, Hobart. (Series: ‘Miscellaneous Collection of Photographs, 1860–1992’ (PH30–1–1459). Photo published over a different caption in The Mercury, 28 August 1936, p. 5. Source: Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)