Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

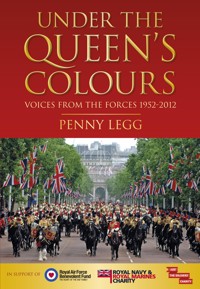

In 1952, Queen Elizabeth ascended to the throne and became the Sovereign Head of the Armed Forces. In the sixty years of her reign so far, there have been thousands of conscripts and regular service personnel who have served under her Colours all over the globe. This book is not just about war, but the everyday lives of those who serve on land, sea and in the air. Service men and women recall their experiences from the years after the Second World War to the Falklands War in 1982, through to modern military service at the end of a millennium and into the first years of the twenty-first century. From life in barracks at home and overseas, in a variety of hot and not-so-hot spots, to being on the frontline in major conflicts worldwide, from Kenya to Afghanistan. Male and female service personnel talk candidly about their experiences, offering a unique glimpse into a world in which they often risk their lives at a moment's notice. Their stories are often laugh-out-loud funny, sometimes deeply moving and always inspiring. Under the Queen's Colours is both a celebration of Her Majesty the Queen's Diamond Jubilee and a salute to the men and women who have served and continue to serve her.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 545

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Respectfully dedicated to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are so many people to thank when producing a book of this kind. I hope I remember everyone. If I have missed anyone, I do apologise and please accept my sincere thanks for all that you have done to make this book a reality.

This book would not have been possible without the contributors, who trusted me enough to tell me their stories and so helped to build up this picture of forces life:

Sid Armistead

Harry Barrett

Raymond D. Bate

Robert Bath

Sylvia Bath

Colin Baxter

David ‘Ben’ Benassi

Peter Bennett

Kai Blackett

John Bocock

Peter Brooks

Jim Brown

George Colman

Mark Commell

Steve Cooper

Victor Dey

Jim Dickson

Brian Dirou

Mark Donaldson

Keith ‘Dougie’ Douglas

Jean Drane

Charles Victor Drane

John Dunlop

Brian Dunn

Don Elbourne

Peter J. Elgar

Warren ‘Noddy’ Feakes

Peter James Fillery

Keith Frampton

John R. Francis

Matt Garret

Elizabeth Gordon

Neville Green

John Gurney

Dillikumar Gurung

Navindra Bikram

Gurung

Dave Hart

Edwin Horridge

Peter Imrie

Mike Jennings

Allan Johnson

Paul ‘Johnno’ Johnson

Tom Jones

Mandy Kazmierski

Des Kearton

Len Keynes

Charles Knights

Lindsay P. Lake

David Lee

Joe Legg

Keith Lenton

Robert Malvern Lewis

Tom Lewis

Jim Linehan

Thor Lund

Neil Lunney

Brian Lynch

Kevin ‘Mac’ MacDonald

Noel Mackey

Bharat ‘Mack’ Makwana

Clint Marlborough

Eon Matthews

Vicki May

Lex McAuly

John McGregor

J.S.D. (Stan) Mellick

Allan ‘Shorty’ Moffatt

Shirly Mooney

Nik Morton

James Mullen

Robert Mullen

Jim Naylor

Ron Nordberg

The late Rodney Nott

Gary William Oakley

Peter O’Brien

Lorraine Osman

William Parry

Bob Pearson

Greg Peck

Mike Pinkstone

Brian Pragnell

Chris Purcell

Mario Reid

Tom Roberts

Ben Roberts-Smith

James Routledge

Dave Sabben

Rob Shadbolt

Douglas Sidwell

Ian Sloan

David Smith

Jim Spain

Allen Raymond Stott

Andy ‘Tommo’ Thomas

Neil Torkington

Dave Trill

Carol Ursell

Terence Warner

Garry ‘Gordon’ Watt

Brian Weatherley

Alec Weaver

Peter Weyling

Chris ‘Knocker’ White

Guy ‘Tug’ Wilson

Gerry Wright

Alex Wylie

Thanks also go to Jo de Vries, my lovely editor at The History Press, who loved the idea of the book from the start and kept me going when the going got tough; Dom at The Army Rumour Service; James at Britain’s Small Wars; Jay Holder at Military Forums; Chris Buswell, QARANC; Nik Morton and the writers at the Torrevieja; Writing Circle, Spain; Derek Stevens; Jim and Mags Parker and the members of the Royal British Legion Riders Branch; Anthony (Tony) Chambers and the wonderful group on the Falklands 30 Facebook site; Robert (Bob) Mullen, who went out of his way to help me with this project; Denise George; Judbahadur Gurung; Vivienne Wood, Royal Maritime Club, Portsmouth; Josephine Shaw; Binu Vijayakumari; Colin Baxter; Jim Brown; Marie Fullerton; Kimberley Linehan; Captain Simon O’Brien, Royal Australian Navy; David Jones; William (Bill) L. Krause, President, Vendetta Veterans Association (Qld); Rob Shadwell, who spread the word; Nina and the team at Gurkhas.com; Catherine Miller, Chris Jones, Wendy Soliman, Glen Mellish, Jacqueline Pye who spread the word on Twitter for me; Mick Heywood; Denny Neave, Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd; Patricia Pollard, Veterans Unit, State Government of Victoria, Australia; Yvonne Oliver, Licensing Officer, Imperial War Museums; Thomas Legg, who knows his Vietnam history; Cmdr Ian Inskip for permission to use his images; Nishara Miles, Office of the Chief of Army, Australia; Brian Davies; Col Mike Richardson, chairman, The Regimental Association of the Devonshire and Dorset Regiment; Laura McLellan and Sian Hexham at the RAF Benevolent Fund; Liz Ridgway at the Royal Navy and Royal Marines Charity; Nikki Lehel at ABF the Soldiers’ Charity.

The biggest thank you goes to my husband, Joe, for all his help and advice, hugs administered in times of stress and all the meals he cooked because I had not noticed the time. This book would not have been finished without his help.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Forewords

Introduction

1The 1950s

2The 1960s

3The 1970s

4The 1980s

5The 1990s

6The Twenty-First Century

7In Memoriam

Websites

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORDS

GENERAL THE LORD GUTHRIE OF CRAGIEBANK GCB LVO OBE

I am delighted to write this short Foreword for Penny Legg. She has come up with a clever formula to bring out the relevance of the Armed Forces to the Diamond Jubilee. The Queen’s long reign has seen an extraordinary contrast in military operations from Korea, a conflict of conventional weapons and warfare, through the withdrawal from empire and the many counter-insurgency operations to the peace-keeping operations on which all services are still engaged today. There has been no pattern to these operations and they have been interspersed with events never envisaged as the services have slowly reduced in size. In 1982 the Royal Navy was in the midst of a review when the Falkland Islands were invaded and in 1991 Kuwait was similarly invaded at the time of the MoD exercise ‘Options for Change’. Both these operations are covered by reminiscences in this book and by the memorial to Signalman Robert Griffin.

Through all this the ordinary soldier, sailor and airman of Great Britain and the Commonwealth have gone about their business in the service of the Queen, doing their best to carry out the wishes of the government of the day. They are seldom concerned in the higher strategy but with the basics of military life always garnered with their inimitable humour. All this comes out well in Penny Legg’s clever anthology. As Colonel of The Life Guards I was most interested in the account of Tom Jones at the time of the Coronation, the start of the story. Equally enthralling to me as a former SAS officer is the story of Mark Donaldson of the Australian SAS who won the VC in Helmand Province in Afghanistan; the end of the story. I am sure readers will enjoy this salute to all servicemen who served in the Queen’s reign.

General the Lord Guthrie of Cragiebank GCB LVO OBE

President

ABF the Soldiers’ Charity

ADMIRAL SIR JONATHON BAND GCB DL

It gives me very great pleasure to be able to write a few words about this magnificent collection of stories from sixty years of Her Majesty’s reign. It has been a time during which much history has been made. We have lived through momentous occasions, with conflicts around the globe from Korea to the Falklands, and of course our current operations, which are very much with us today.

Throughout these six decades it has been the men and women who serve Her Majesty, in all of our Armed Forces and in all their own wide variety, who have ‘gone out and done it’. It is their sense of duty and of purpose that richly reflects that of our sovereign; but above all it is the comradeship and camaraderie that is the defining fact of military life.

This excellent new collection of stories from all of our services captures this sense and laces it with the ever-present humour that is part and parcel of life in uniform. In thanking the author for her prodigious efforts in producing this timely and immensely fun anthology, I do so on behalf of all service charities, who play such a vital role in the life of our people and their families. I hope that you enjoy the time travel as much as I did, as it portrays the real life stories behind the headlines, and above all reminds us of why we all elected to serve under the Queen’s Colours.

Admiral Sir Jonathon Band GCB DL

President

The Royal Navy and Royal Marines’ Charity

AIR MARSHAL SIR ROB WRIGHT KBE AFC FRAES FCMI

In 2012 the United Kingdom will commemorate sixty years of the reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Her Majesty is closely linked with the Armed Forces, not only as Commander–in-Chief, but on a personal level as a service wife during the early days of marriage to HRH The Duke of Edinburgh. Her Majesty has also been Patron of the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund for sixty years.

During all of that time, our nation has changed immeasurably. One constant has been the sense of humour expressed by British serviceman and women often under adversity, as you will read in many of the anecdotes and stories shared in this book. Life in the services is not straightforward. It is an often complex life, with periods of high pressure tempered with periods of preparation, routine activity on standby, operational deployment or on exercise. Separated from family and friends, often at some distance away with limited communications, sharing of stories and humour help to ease times of anxiety. After forty years as a serving officer in the Royal Air Force, I have enjoyed the fact that so many ex-servicemen and woman have happily shared their stories for a wider audience.

The Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund was founded in 1919 in order to support those who had served in the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force during the First World War and were in need of financial support. Today, we continue that mission, supporting members of the RAF family who are in need – irrespective of when they served or where. Some of those we help today saw action during campaigns and operations throughout the past sixty years. Others are children and dependents of those currently serving with the Royal Air Force. The Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund exists to help them all. I am delighted that a share of the proceeds of this book will support our ongoing work with those members of the RAF family who are in need, today and in the future, and this will help us to repay what Churchill memorably called the ‘Debt we owe’ and which is the motto on our crest.

Air Marshal Sir Rob Wright KBE AFC FRAes FCMI

Controller

Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund

INTRODUCTION

I have long wanted to produce a book of service reminiscences. If you listen to the average person who has spent any time in the armed forces, you will soon hear tales that are laugh-out-loud funny, make you think or bring a tear. It was this variety that I felt should be heard. I was thus very pleased when The History Press liked my idea and agreed to commission this book.

It is not every day that a sovereign reaches sixty years on the throne of a country. I wanted the chance, too, to produce a book to celebrate and commemorate Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee and to be able to do so is a real honour. The added bonus is, I am able to contribute to service charities in the process.

I have lost count of the number of organisations and individuals I have spoken to for Under the Queen’s Colours. I have been to countless meetings, explaining what the book is about and what it wants to achieve. Messages went out to organisations all over the UK and further afield, and I joined websites and forums to spread the message – I needed contributors with stories to tell and photographs to illustrate the words. Those who came forward ranged in age from their 20s to 91-years-young.

It was my privilege to meet some super people with stories happy and sad to commit to posterity. They showcase the sheer variety of life in some of the armed forces serving Her Majesty.

Some of the contributors to this book wished to write their stories down themselves, whilst others were happier to be interviewed either face to face or over the telephone. I stopped people in the street at veterans’ events and listened to anecdotes, Dictaphone in hand. I travelled to people’s homes and listened to their stories over a good cuppa and, if I was lucky, a chocolate digestive. Contributions came in from across the UK, the USA, Spain, Australia and Nepal. In the end, I was simply amazed at the response to the book and I would like to thank publicly all those who came forward to bring the book to life. I wish I had been able to use all the material I was offered. I had six months to produce Under the Queen’s Colours and I was a busy girl during that time.

Tom Jones, of The Life Guards, remembers the fuss caused by Princess Elizabeth’s wedding in 1948. He was stationed in Palestine, having served throughout the Second World War. His recollections serve as a taste of the affection felt for Her Majesty by service personnel throughout her reign:

‘We were stationed in Jerusalem. We were on troop catering. We worked hard. We slept little. Morale was very high as we had superb backing from an excellent squadron leader in Major Scott. We bragged we never missed a duty thanks to a great troop leader, and the fact I was a mechanic in civvy life helped, as we did all our own repairs. I could not have handpicked a better bunch to be with. When the news came that Princess Elizabeth was getting married and would have a full Household Cavalry escort, there was great excitement. Then we learnt that the horse soldiers were rubbing their hands, and for good reason – they were going home. Off they went, and we were working eighteen hours a day (to cover for them). To be fair, everyone got stuck in, and nobody moaned.

‘Sleep was at a premium, but we had always had this problem, so we shared the tank driving and all took turns, and we took turns in the gunner’s seat, where you could close your eyes. We were a great team, lead by a great team. We enjoyed the work and the company, even if it was hairy at times.

‘After a while – I cannot remember how long – they returned. The horses were in good nick, and had been well looked after. The uniforms had been in a terrible state and they had to start from scratch (for the wedding), but it all went well on the day, even though a lot of makeshift repairs were done. We got back to normal, with those who had gone to the wedding ever remembering more bits of information. We felt proud. Whilst we were not there, we had done our bit.’

King George VI died in 1952 and the popular princess became a much-loved monarch; Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Queen Elizabeth I of the Commonwealth.

John Dunlop remembers when he was an excited 13-year-old cadet midshipman in the Royal Australian Naval College in January 1954, eager for a glimpse of royalty:

‘Our first outing from the College was to line Saint Kilda Road, in Melbourne, for the drive past of the Queen and Prince Philip, on their first visit to Australia.

‘Within a month we had to be trained in the parade ground drills necessary to appear smart and co-ordinated as we took up our places along the route. We had to learn how to manage the dress uniform of the day – the Royal Australian Navy still required detached collars, with collar studs and cuff links, for our uniform – quite a challenge for some of our cadet entry, who had never worn shoes before! We also had to learn to stand absolutely still for over an hour.

‘We performed all this with great pride, only to be mortified when we were mistaken for first aid staff by some spectators!’

The contributors’ stories that follow have been reproduced as faithfully as possible to their own words. They are presented in rough chronological order from the earliest in the Queen’s reign through to the present. The photographs in this volume are largely those taken by the contributors themselves. The rest are credited to the appropriate person where this has been established. If you recognise a photograph as yours, please contact me to make the necessary arrangements.

This book is both a celebration of Her Majesty the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee and a salute to the men and women who have served under her colours during the long years of her reign so far. I hope you enjoy the pages that follow.

Penny Legg

2012

1

THE 1950s

During the 1950s, whilst Britain was still coping with rationing, war was never far away. Korea had the distinction of being the first conflict sanctioned by the United Nations and there was combat in Vietnam, Kenya and Malaya. The Iron Curtain came down and rock ‘n’ roll arrived. In the United Kingdom, Princess Anne was born, a king died and a queen took his place.

EARLY DAYS

JIM BROWN was a National Serviceman who served under both the King’s and the Queen’s Colours.

I joined the army for my National Service, at the age of 18, on 20 July 1950. I had previously matriculated at Southampton’s Taunton Grammar School so the authorities, in their infinite wisdom, posted me to the Royal Army Educational Corps, (RAEC). I then did my basic training with the 1st Battalion the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC, known as the 60th Rifles), at Bushfield Camp, Winchester. On enlistment all recruits had to take the oath of allegiance to King George VI. In earlier times this was known as ‘taking the king’s shilling’.

The 60th Rifles were responsible for the basic training of some of the RAEC. Others were trained with the Welsh Guards at Beaconsfield. We had three months’ intensive training in how to kill in various ways: bayonet, Bren gun, Sten gun, hand grenade and, of course, rifle! As a rifle regiment the Lee Enfield .303 was almost worshipped and there were many marksmen in the KRRC, several of them champions at Bisley, where top-level shooting competitions were held.

It was an offence akin to murder to have a dirty rifle, and this resulted in my first experience of being on a charge and then punished, otherwise known as ‘jankers’. The background was that we had been on a night exercise that involved wading through the River Itchen in full combat gear, carrying our rifle. We returned to Bushfield at 6.00 a.m. and were told to parade at 6.45 p.m. in best uniform for an inspection. I passed mine, the inspecting officer having checked my rifle in some detail, but a comrade some way after me was asked to remove the spring from the magazine, when a tiny speck of rust was found. To my horror, we were then all told to remove the spring from our magazines and, lo and behold, mine also had a very tiny speck of rust! This resulted in a sentence of seven days’ confined to barracks, carrying out fatigues every day.

National Serviceman Jim Brown, taken when an 18-year-old sergeant in Germany by a German photographer in his studio, in exchange for a tin of Nescafé.

Fatigues involved having to parade outside the guardhouse every morning and evening, with the other defaulters, when we were allocated various duties – such mind-blowing duties as renewing the whitewash on the brick edging strips along some pathways, or cutting the grass edgings with a large pair of scissors! One of the more welcome duties was peeling potatoes and preparing vegetables for the sergeants’ or officers’ mess. At least one was warm and dry, with something to nibble; the other duties were carried out in the open, regardless of the weather.

On my first defaulters’ parade, when it came to my turn, the provost corporal (one of the regimental policeman) screamed at me, ‘Go in the guardhouse and get a brush.’ I ran as fast as possible into the guardroom, opened a cupboard and grabbed the first brush I saw. When I returned, still in mortal terror, the corporal looked at the brush, saw I had in my haste collected a wire brush, and again screamed at me, ‘Go to the rear of the guardroom and scrub the dustbin – I’ll teach you to do what you’re told.’

I then found an old rusty dustbin, full of refuse, that I had to first empty out and then scrub with the wire brush. I looked up and saw the corporal sitting back in his chair, feet on the table, reading a Health and Efficiency naturist magazine with photos of nude naturists. Directly I eased off the scrubbing, as my arm started to ache, he heard the change in noise level and screamed out for me to scrub harder. By the end of an hour my entire body ached as it never had before, and my hatred of the corporal built up to the point where I could cheerfully have murdered him.

Jim Brown’s hut in the RAEC training camp outside Bodmin, where six trainees lived.

My initial basic training eventually came to an end and we were posted to Bodmin, Cornwall, to receive our educational teacher training. When we arrived at the station, we were joined by a similar collection of RAEC recruits who had been trained with the Welsh Guards at Beaconsfield. The marching speed of rifle regiments was 140 to the minute, compared to the standard rate of 120 to the minute, quite a difference, so when Bodmin’s company sergeant major (CSM) formed us into two groups to march us to the camp, some several miles away, there was absolute chaos. The Welsh Guards-trained recruits in front marched at their usual ponderous pace, whilst we behind them from Bushfield marched considerably faster, bumping into the rear of the Guards’ group. We had to stop and were ordered to go to the front and lead the group, whereupon we tore away leaving the other half 100 yards behind. The CSM swore and screamed, but no matter what he did the Guards group deliberately marched even slower whilst we marched even faster. It was the best fun we’d had since joining up.

We received intensive classroom training and at the end of the first month those who passed the first examination received their first stripe to become lance corporals. At the end of the second month we became full corporals, with two stripes, and at the end of the third month – we who survived – became the proud owners of three stripes as sergeants. This was to ensure we had the appropriate authority where we were posted to our respective regiments as the regimental schoolteachers. We were then individually interviewed by the commanding officer and asked where we would prefer to be posted.

Jim Brown, seated centre, outside the sergeants’ mess. Taffy Barton is with him and two 60th Rifles sergeants. Their stripes were black with red edging, they had a black leather belt and they wore a black lanyard on their shoulder. This denoted that they were in a rifle regiment.

The newly arrived influx of education sergeants outside the sergeants’ mess in Brigade HQ Hanover.

As I had taken German at school I asked to be posted to Germany, to BAOR (British Army on the Rhine). This was only a few years after the war and we were still considered to be an occupying force. I arrived at Hanover, via a boat train from the Hook of Holland, my very first trip abroad, and was given a choice of available regiments that needed an education sergeant.

The block of apartments on the right were duplicated throughout the Paderborn barracks, and senior NCOs, such as Jim Brown, slept in the end apartments. The sergeants’ mess can be seen in the background, behind the garages.

I was surprised to learn that whilst I had been in Bodmin, the 60th Rifles had also been posted to BAOR and were stationed in Paderborn, a small village in the North Rhine Westphalia area of Germany. I was delighted to learn that they needed an education sergeant and requested a posting to my former training regiment. This was granted and, in due course, I arrived at their barracks, former SS ones, in Sennelager, on the outskirts of Paderborn.

When I arrived at the entrance, carrying my suitcases, who was on duty at the guardroom? None other than the provost corporal who had tormented me with the wire brush! He did not recognise me but, in view of my three gleaming white stripes, detailed a rifleman to carry my suitcases for me and to escort me to my personal flat in the barracks. I said nothing to him but resolved to wait until I had him in my classroom. This took place the following week, once I had settled in.

The army had recently decided that all wartime ranks had to obtain their appropriate Army Certificates of Education to retain their rank. The warrant officers, CSM and RSM (Regimental Sergeant Major) had to obtain the Army First Class Certificate, and other ranks the Army Second Class Certificate. There was a second RAEC sergeant, ‘Taffy’ Barton, who joined me within a matter of days, and we both worked hard at attempting to get the various ranks to pass their respective exams.

My hated provost corporal appeared in my class in due course, anxious to qualify, and was at my mercy. However, by then I had understood that what he had done was part of instilling discipline into a soldier and was part of what was really a game. I was now a sergeant and part of the same game. I also found that the corporal was actually quite a decent chap and I was never tempted to inflict anything on him, such as exposing his ignorance of things to the rest of the class.

There are many aspects of army life that I could discuss, but one that springs to mind was one day when I had been talking to the RSM. He was the most important man in the regiment, next to the commanding officer, as he was responsible for discipline and overall organisation of virtually everything. He was equally feared and respected.

One thing that I had found hard to believe was that whilst in the mess it was Christian names throughout, regardless of rank. One’s beret and belt were removed on entering the mess, and we were all then ‘off duty’. This particular day I had been talking to the RSM in the mess, when it had been ‘Jim’ and ‘Bill’. We left together, replacing our berets and belts as we left, and continued talking as we walked along to our quarters. I happened to call him Bill, when he froze, looked at me horrified, screamed at me to stand to attention and then proceeded to give me the most terrifying dressing down I had ever had. I had overlooked the fact that we were now ‘on duty’ and he was ‘Sir’ at all times. It was a lesson I always appreciated.

I had enlisted and taken my oath of allegiance to King George VI but he died on 6 February 1952, whilst I was stationed in Paderborn. I recall that we were paraded and addressed by the commanding officer, a colonel. The regimental band played a slow march as we marched around the parade ground.

We were informed that our allegiance was now to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and we all had to salute, as we were dismissed from the parade, in acceptance of this change. I believe that all officers wore a black armband until the King’s funeral took place. I was now a soldier of the Queen, something that had not happened since the time of Queen Victoria!

SERVICE LIFE

JOHN BOCOCK was called up for National Service in the early 1950s and found himself posted to Egypt.

I was put on a draft to Egypt. I wasn’t too fussed. I knew that with the amount of time I had to serve in the army that I couldn’t be away for too long. This, in some small way, helped poor Vera (my fiancée), who I think thought I was disappearing for ever. However, the embarkation leave (fourteen days) was lovely and we pledged our troth again and promised all sorts, and off I went.

John Bocock, in Egypt, with his 4 x 4 truck.

Port Said was mind-blowing – so much activity and my first taste of non-European people. I remember bumboats alongside our boat on arrival, flogging us goods by way of a line being thrown at the boat – load of rubbish, as I recall. They were also buying gear from us, watches etc. This continued as we made our way to the waiting train, which was going to transport us to our respective destinations. I ended up halfway down the Suez Canal, a place called Fanara. It was a working company. I was then posted with two or three others to a base ammo depot further up the canal, which was to supply the transport for the RAOC [Royal Army Ordnance Corps].

I clearly remember, with I think four other trucks, going out into the desert to a particular site with phosphorus, which was dumped. We were then ordered to drive at least half a mile and then it was blown up. Quite a display!

In addition to the regular duties there were other duties, like driving up to about 30 miles and picking up civilians who worked at the camp. We used to go off at about 4.30 a.m. for this.

On several occasions one of the civvies was a Sudanese, very dark and quite intelligent. He was something like a chief clerk. He spoke good English so I used to get him to sit in the front so I could pick his brains and try to pick up some Arabic. It was very interesting. I can still count to twenty in Arabic.

Another duty was concerning the Royal Military Police Dogs. They had a small detachment on the camp. This entailed going to their lines and picking them up.

They each had a dog, which was their own, also up to three dogs that were ‘barkers’, which were placed at strategic spots across the depot to deter anyone breaking in.

In addition to these duties there was a guard company who also had to be, like the dogs, taken to various other spots, again to keep out intruders. It was really just an open depot, no fencing or anything like that. Those guards were all black and were from Mauritius, didn’t have much to say.

I was gradually getting used to my 4 x 4 truck and after picking them up as usual I got stuck in the sand, so it really was black looks all round. Lucky for me a half-track came along and pulled me out. I made sure it didn’t happen again!

CALL-UP

ROBERT BATH served his National Service in the Royal Air Force in the 1950s.

Before I was called up for National Service, I was working at Westland at Yeovil as a miller. I had deferred my call-up several times and then found out that if I wanted to defer again, I would have to move sections in Yeovil. So I decided to accept my call-up and when I was down at the selection centre, I told them that I wanted to join the RAF. They told me that they already had their quota for the RAF for today. Then the chap looked at my details and saw that I worked in the aircraft factory and he said, ‘Oh, you can go in the RAF – the chap before you is only a painter and decorator so he will have to go in the army.’ So I got in the RAF.

National Serviceman Robert Bath.

RAF Hednesford, new entry class 1954.

I went and did my basic training at RAF Hednesford in Staffordshire and then you were allocated a job for your two years’ National Service. If you wanted a trade you had to sign on for three years, but I didn’t want to sign on for three years if I didn’t like the RAF, so I got a job as a wireless operator. I went down to Compton Basset in Wiltshire to do my training, which was learning to do the Morse code. I was there about three months I think, and then I got posted to RAF Gloucester to aircraft control at Gloucester, where I used to operate sending the weather forecasts to the aircraft. They used to call you up and ask you for the forecasts and that was mainly what you did there. I was there for about six months and then I got transferred to RAF Ouston, which was near Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, where we were put on mobile units and we used to go round to various stations for about a month at a time monitoring the flying aircraft. A mobile station was a large truck with what looked like a box on the back, and the radio units were inside.

We used to deploy to stations such as RAF Valley in North Wales. We would monitor the aircraft flying to see that they were not using the radio equipment illegally by sending messages back to their family. The people on the camp never knew what we were up to. They got told that we were testing experimental equipment. They didn’t want them to know what the reason was we were there.

Robert Bath’s Royal Air Force Discharge Certificate, dated 6 April 1956.

It was quite interesting. We moved around quite a bit. We did a month on each camp. Because we were working in the mobile units, on the end of runways, we were given flying suits to wear to keep us warm. We were working in the back of the wagon but because there was no heating in the wagon that’s why we were given the flying suits, as North Wales is pretty cold in the winter.

On a Charge

When I was at Compton Bassett, one of the WRAF [Women’s Royal Air Force] Sergeants was being presented with a medal, and we all had to go on parade. I got put on a charge for having long hair and got put on jankers for seven days in the cookhouse. I had an easy job because I was just serving the food. Luckily, I didn’t have to peel spuds or anything like that.

I enjoyed my two years in the RAF but enough was enough and I didn’t sign on for any more and went back to Westland.

MAKING MEN

Serviceman No. 2/704019 JIM SPAIN says of himself …

I am an ex-Aussie National Serviceman, 1951–54, and completed voluntary service in 1964. I am a retired Royal Australian Signalman, but an on-going member of our Royal Australian Signals Association. Since retirement I have taken to writing verse. It keeps me out of gaol.

I have written Making Men. It speaks of those National Service days, the trials and tribulations, the good times and the bad. Also it speaks of the groundwork that was laid to turn many of us into men:

A BUGLE IS BLOWN IN THE HALF-LIGHT

BEFORE THE ROOSTER CROWS,

IT BEGINS EACH DAY IN THE ARMY

AND THAT’S THE WAY IT GOES.

This; the start of army training under National Service call,

three months full time service

as each eighteenth year would fall.

From the east and western suburbs, the north and south as well, from every point of the compass,

wherever young men dwell.

They said goodbye to their loved ones

and made their way in droves,

to assemble at the depots,

they were rich and poorest coves.

A ragtag bunch of young men

to be taught and trained for war,

to start both legs had left feet,

a sorrier sight you never saw.

Army trainers attempted line-ups,

but they snaked across the field.

Each recruit was with his best mate

and soon it is revealed,

they would go to different sections,

splitting friend and foe apart.

But you might as well accept it.

If you want the right start.

They were grouped and formed into companies,

each bound for different camps.

By bus and trains they travelled

with the first night lit by lamps.

Fly covered tents and canvas

marquees, all set out row by row,

this type of living quarters

many young men did not know.

Wood framed beds with palliasses.

Two blankets, and to be sure,

you can sleep on top of a bare board,

when you are weary; worn; and sore.

A single cupboard beside you

to stow your personal gear,

it must always be spic and span son,

each day throughout the year.

They slump in their beds the first night.

Tired: aching, sleepless and then

roll call is early the next day

and they begin to wonder when they will ever get to ‘sleep in’:

before next day comes again.

THE BUGLE SOUNDS IN THE HALF-LIGHT

BEFORE THE ROOSTER CROWS,

THIS IS START OF LIFE IN THE ARMY

AND THAT’S THE WAY IT GOES

A roll call is start of each day.

It is the very first parade.

All recruits still dressed in mufti in an army camp charade.

Because soldiers parade in their uniform:

each, all and everyone.

The ‘grunts’ right through to the top brass,

all brilliant in the sun.

When finally no one is missing, all counted:

but not knowing where.

Hearing instructions shouted as orders.

Some start to feel despair.

Not knowing the immediate future

and under strange conditions

the recruits are marched to the ‘Q’ store

for uniforms and provisions.

Hob nailed soles are fitted to brown boots

that must be blackened and cleaned.

The method to achieve ‘spit polish’

really has to be gleaned.

Slouch hat, Web-belt and Gaiters.

Rifle, Bayonet and more.

Work dress, K.D.s and Dixies;

all issued from the ‘Q’ store.

Next days are used cleaning gear up,

everyone sorting out,

learning to know the camp layout

and what ‘NASHO’s’ is all about.

Footdrill, marching, saluting:

getting to know the score.

Stripping and cleaning the rifle:

knowing the butt from the bore.

Marching, marching, marching:

over and ’round the ground.

Knowing to follow orders.

For some: discipline is newly found.

Training, becomes more varied,

interest continues to climb,

in the quest to be almost perfect,

you do it again –

‘One more time’.

Parades and exams seem endless.

Some qualify for the first stripe.

Prestige and authority accepted,

will be useful the rest of your life.

Some are chosen: and then named ‘STICK BOY’.

Those duties allow you to glean.

What goes on in the senior areas.

What extra responsibilities mean.

Others initiatives are tested; subtly:

and they do not know when.

But be sure if you have the ‘Right Stuff’:

you’ll be watched by the R.S.M.

Physical training is one of the disciplines

to ensure that everyone’s fit,

it’s only one of the numerous abilities

they all to have in their kit.

So too is firing the rifle, stretched out:

prone on the ground,

while hundreds of .303 bullets,

go thundering away to the mound.

Markers lower the targets,

then by raising them back to the sky,

it can be seen there’s not many that get very close to bullseye.

It’s twenty-five yards, not too distant,

should be easy to shoot.

But as they keep on missing,

the sergeant yells

‘Stop firing at once.

‘All of you, lower your weapons.

‘You might just as well throw – YOUR BOOT’.

Remember the time at the test range,

practising with the Owen and Bren.

Machine guns that spit out bullets:

again: and again: and again.

N.C.O.s warn of the danger

machine guns: easily kill

practice, practice and practice

until you’ve got the drill.

For if you turn with your weapon

and it’s not facing the ground,

expect to be crash tackled

and forced face down to the mound.

The days: then the weeks move quickly.

Most skills are now firmly drilled.

They are practised and polished and perfect,

discipline is firmly instilled.

You feel, and look like ‘The Digger’

who marched away to war.

Their battles and their bravery:

fixed firmly in Aussie folklore.

Now, you may never have to use them,

fighting battles on any war front,

but be certain that they will be useful

and about this,

I can be blunt.

The habits and knowledge you now have

will stand you in good stead.

You can use them as you must do, as a

Leader who is not Led.

But, always you will REMEMBER.

Whenever a trumpet sounds,

that

A BUGLE IS BLOWN IN THE HALF-LIGHT

BEFORE THE ROOSTER CROWS.

THIS IS

THE

LIFE IN THE ARMY

AND THAT’S

THE WAY IT GOES.

LIFE AS A DRIVER

JEAN DRANE, née Parker, joined the Women’s Royal Army Corps as a driver in May 1953.

It took ten weeks to learn to drive but it wasn’t just driving, it was map reading, mechanics and also administrative information like what kind of petrols/diesels to put into the lorries – they needed you to know all that kind of information. That was the only one I failed on and took it again and passed. The administration was more difficult than the driving and the mechanics!

My first vehicle was an Austin KT ambulance. It was known as a ‘Tilly’.

Jean Drane when she was an Army Cadet.

Jean Drane’s WRAC graduating class, 1953.

I went to Hounslow after I passed my course. I got off the Underground and crossed the road. A horse and cart was common in those days so I don’t know why he caught my attention. He saw me and said, ‘Want a lift? I’m going past the barracks.’ So I said, ‘Yes please, because my kit bag’s heavy,’ and he dropped me off by the gates of Headquarters Eastern Command Hounslow. I actually worked there but slept in 70 Company’s barracks.

Jean Drane and her Tilly ambulance.

One of my first jobs was with the local postman. He was at the local sorting office and I would pick him up at six o’clock in the morning and I would take him to all the various departments of the barracks. Prior to that, I would help him with his sorting, if I got there early enough. I had to be up at five, get over to the mess, have some breakfast then pick up the vehicle and drive it to the sorting office, which would take twenty minutes. I would get there early and help with the sorting. I used to enjoy doing that.

One day I didn’t make it. I overslept. So they put me on a charge and I got four days’ CB (Confined to Barracks). I wrote a letter home to Mum letting her know that I got this CB. She, unbeknownst to me, told everyone that I’d been given a medal! One person said to my father, ‘Well done to Jean for getting the CB.’ Mother was telling everyone I’d got a medal and I’d got confined to barracks!

I used to drive a Tilly, which was really old but they were lovely. I would overtake all the traffic and then I’d take off and I’d be away.

I was asked to test drive a Land Rover. I quite enjoyed driving her but I was up the North Circular Road doing 40mph when the bonnet came flying up. I didn’t do anything silly like an emergency stop – it was not that busy in those days – so I stopped by the side of the road and jumped out. The clips had come undone each side. I managed to get them back on and reported it. I was told that that particular fault is what they had been looking for. Land Rover had the front spring-loaded clip put on after that.

One day I was in my Tilly and I pulled up at lights in the Pentonville area behind a big, black Maria. I hit it. The next thing, I’m surrounded by all these guards! About six of them all came flying out, a couple at the front, a couple at the back. I was surrounded! I got off with it; I was lucky.

One job I had was being detached to Woolwich, working with the married families – all the wives of serving soldiers. I took pregnant ladies having babies to hospital; foetuses to St Thomas’ for autopsy. I even took a 19-year-old soldier who had died and his mother there. I did a number of different jobs.

ARRIVAL

BOB PEARSON was born in the UK but became an Australian citizen. He served under the Australian Command in Korea. He paints a forlorn picture of the country when he arrived there soon after the start of the war.

The whole ocean journey took over five weeks. Our destination was the port of Kure in Japan, about 20 miles from Hiroshima, the site of destruction by the atom bomb. This was headquarters for the British Commonwealth Overseas Force and included our own SIB/RMP [Special Investigation Branch/Royal Military Police] headquarters. On arrival, our commanding officer welcomed us with an orientation brief for what had happened so far and the work we would be expected to cover, in a country with difficult terrain and climate. He said Korea was under war conditions. It was intolerably hot in summer, and winter temperatures well below freezing. He added that there had already been casualties, with one Special Investigation Branch sergeant murdered by Philippine troops and another NCO evacuated with mental stress. There would be some investigators earmarked for postings in Japan or Korea. Jock Corrigan and I immediately volunteered for duties in the forward area with the Commonwealth Division and our offer was accepted.

The next day we left for Pusan, in an old steamer. It was such a small transport ship compared with the large vessel we had spent the last few weeks on. It bobbed and weaved across the Korean Straits, a very rough crossing indeed. By the time we approached Pusan there were many green faces hanging over the ship’s rails, all looking forward to being back on terra firma. It was a cold, grey, miserable, rainy morning as the ship approached the wharf, but our frowns after such a harrowing voyage turned to smiles to see the welcome committee.

Bob Pearson and friends in Seoul, 1952.

On the quayside, an American-Negro military band moved in slick formation as they played us ashore, to old Glen Miller melodies. When the Saints Come Marching In and In the Mood echoed around the docks. It was music to lift our somewhat dispirited attitude. Apart from such gladdening music, their dress and precision marching were brilliant. They were excellent performers and a very cheerful sight to behold that made us feel most welcome. So we were at last in the country known as ‘The Land of the Morning Calm’; a land that had been torn apart and conquered so many times; a land that very few people knew much about, except that its people had been subservient for centuries and was more akin to the ox and plough than any modern concept. I was also to discover that a national flower, the Azalea, was to become a favourite of mine. Even though I did not know what to expect in this new country, it had a feeling of despondency about it because of its drabness. Somehow, I had expected the place to have the colour and excitement that Europeans come to associate with the magical Far East.

Pusan, one of the main Korean ports, consisted of large areas of buildings and stores of all shapes and sizes, with a confusion of military vehicles, supplies and equipment stacked around the place. It had an aura of dilapidation, like a city that had been left to decay. I was grateful I had not been posted there. The American band was the only bright thing I saw in my brief stay. Worst still was the effect of days of constant rain that left us treading in black slimy mud in many places.

After a night of boozing, we left the next day, complete with hangovers, by train for Seoul.

At this stage in the war, the frontline was north of the River Imjin and Seoul, just beyond the 38th Parallel. We were to find that there was not a bridge left standing between us and the enemy except for a hasty repair of the Han River Bridge in Seoul, which had been destroyed in the Allies’ retreat from there the previous year. The bridges that spanned the Imjin in our sector were only temporary. They were military pontoons called Pintail and Teal, which was always cause for concern because of imminent floods and the possibility of a Chinese advance.

The skyline of the city of Seoul was a conglomeration of buildings; there were historical oriental, pseudo-modern and an abundance of mud huts. Most, especially ornamental stone buildings, were pitted with shell and shrapnel scars. The evidence of war was everywhere, as Seoul had taken quite a pounding when the North Koreans had moved through, then again when the Allied forces had retaken it.

There were no high-rise buildings, as one would expect in a capital city. Most of the stone buildings were of traditional style with curved and often painted roofs in red and green colours. We were only situated about half a mile from the main government building, but on the alleys on both sides of our dwelling were long rows of mud huts, a sort of shantytown, the majority of which were brothels. In the dusty streets there was a constant noisy flow, back and forth, of military vehicles either going to or coming from the forward war area.

In Plaster

I was injured in Korea and sent to Kure in Japan for ‘R and R’ leave. Whilst there, and on my final night, I was taken by an Australian petty officer around the fleshpots of Kure. I had a plaster cast on my leg from hip to ankle (administered by the Canadian MASH after falling over).

It was a night to remember but I was amazed by the kindness shown to me by everybody, including Japanese citizens. Everything was ‘on the house’. Just before I left the following morning to return to Korea, I commented to the Aussie PO about the generosity of everyone. He told me that he told everyone I was a wounded soldier from Korea, albeit he knew I had fallen over to sustain my injury. After pleading that I was merely injured, he replied, ‘Yes, but they didn’t know!’

It was going to be wonderful after two months of discomfort, as the Australian sister at the British Base Hospital in Seoul came to arrange the removal of the plaster. She smiled at some of the cute poems and drawings, which comrades had emblazoned on the white plaster. Then I saw a look of horror on her face as she bent forward to examine the drawing of a Spanish lady. Throwing up her arms in the air she shouted, ‘You’re disgusting, Sergeant. Is this what policemen do? I’ve a good mind to let you wear this damned thing for another twelve months.’

I could not understand what she was raving on about and after questioning her she pointed to the Spanish lady.

‘That, that …’ At a loss for words, she straightened her trembling arms at her side and with fists clenched, cried out in disgust, ‘Ugh … that filthy drawing.’

‘Filthy? … You mean the Spanish lady with the flower in her mouth?’

When she saw the drawing from my viewpoint, she realised what had happened, but she was so offended that she left the room and appointed an orderly to cut off the plaster. He thought it was hilarious. I was very embarrassed when I saw the sketch another way up. It was a female, showing her anatomy with legs akimbo. The orderly was so pleased with it he asked if he could keep it to show his mates!

The Irrepressible Kim

On our arrival in Seoul in the spring of 1952, we were billeted in an old but substantial house that still bore the effects of the last battles. In the line we were able to have showers once a fortnight, together with clean clothes, but in Seoul we actually had a bathtub. It was also dependent on our Korean labourer Kim to work it. Kim was a middle-aged toothy, grinning Jack of all trades, and a rogue to boot. He was suspected of re-routing the brigade power supply to the brothels nearby, but it was never proved.

When Kim came to fit a light in our room he stood unsteadily on a chair, then, with arms above his head, he first secured the fittings to a single wire that hung down. This was followed by his unique way of testing – after wetting one forefinger in his mouth, he plunged the finger into the socket. This was followed by a shout, a look of pain, a toothy smile, followed by the words, ‘Iss Ockay, Sergeant san’.

On the special days when hot water was to be made available, Kim made his way down into the cellar. Here he had his own invention of a hot water system. Two 44-gallon drums welded together for the boiler, attached to which were a horde of pipes and boiler fittings. At the base of the boiler was a rectangular cut-out for the fire-hold. Using a volatile mixture of diesel fuel and petrol for ignition, he would light the contraption and then gallop out of the way up the stairs. A few seconds’ wait and there would follow an explosion that sent clouds of smoke billowing out. Another short delay and he would then announce, ‘Hot water come soon, Sergeant san.’

The smoke and fumes that permeated the house for ages were terrible, but we were grateful for his efforts. There were times I was sure that Kim would do the wrong thing and be carted off to the nearest gaol, but he just sailed on through life, always smiling and, I believe, always plotting his next crime. He had been through the effects of two armies trying to obliterate his way of life, but he always had a toothy grin for one and all and a zest for life.

WHAT STAYS WITH ME

GEORGE COLMAN served in Korea in the Royal Australian Navy. He has contributed the following story, the first of three from the project In Our Words, an initiative of the State Government of Victoria.

I was on duty in the range finder director, the gun control system on the bridge of HMAS Condomine. An American minesweeper under fire sent an SOS. We had to go in, lay a smoke screen firing our 4in guns to escort the minesweeper to safety from North Korean guns firing from shore.

After the rescue was completed it was rumoured that HMAS Condomine was sunk with all hands, except one who was in sickbay with appendicitis.

Naval intelligence sent a Canadian destroyer to find out if this was true and found us sitting safe and sound on station. It was all propaganda – we were disliked very much by the North Koreans!

What stays with me was the fear of being fired upon.

The real claim to fame was that we were still there in the morning.

I also remember night patrols. Every half hour we would fire star shell to light up any North Koreans running between the islands laying mines.

What really stays with me was ice and snow, the freezing cold and stinking heat in the summer.

The Island of Paeng Yong Do was very poor and continually under fire from North Korean guns. When we arrived to bring presents and food to the women and children they were incredibly grateful.

After all this extraordinary situation, I’d still return if need be. I thought it was my duty to help South Korea fight for their freedom from communism, under the United Nations flag.

TRAINING

CHARLES VICTOR Drane was called up for National Service in the British Army in the early 1950s and then joined as a regular.

The first time I went into the army I did my basic training at Black Down, near Deepcut. There has been a lot of talk about Deepcut for quite a few years. It wasn’t the best of places but it was OK. It was somewhere to live. We did six weeks’ basic training and in those six weeks we learnt the basics of marching, saluting, drawing your pay – which were important things – and firing various guns; how to be a soldier. But getting your pay, as far as I was concerned, was the most important part. When I went in our pay was 21 shillings a week. Which, if you worked it out, meant we were there for twenty-four hours a day for seven days and it worked out at 3 shillings a day (15p). They had your heart and soul for twenty-four hours a day for that. You were at their total beck and call, no matter if you were trying to sleep or not.

We had to do the usual things like guards. All the things you would do in the army – you learnt how to maintain your kit, what to do. It was very hard. It was a different army in those days. You got screamed at a lot. There was a lot of unnecessary brutality. There was a lot of bullying. The reason for this being that a lot of NCOs were National Servicemen and were only there for two years anyway and the fact that they got to be senior NCOs went to their heads. When I first went to join the army, they talked about standing to attention to speak to an officer. We used to have to stand rigidly to attention to talk to a trained soldier as well as an NCO because we were recruits. We weren’t even soldiers, you see. We were the lowest of the low – untrained civilians.

Charles Victor Drane, who joined the army first as a National Service Conscript and then as a Regular.

I stuck that for about a year.

I came to Portsmouth to do my trade training at Hilsea. Then I went to Bicester, Oxfordshire. I stayed there for a while. I passed education tests and various bits and pieces at Bicester and then I decided to join the army full time. So, I signed on for three years. I became a regular solder – there was more money – about £3 a week, as opposed to 21 shillings. The monetary incentive was there!

MY BACK

MAJOR ALEC WEAVER, 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment, remembers this amusing prank in Korea.

I was a privileged member of a few aides assigned to the commander-in-chief of the British Commonwealth Forces in Korea. His official residence was located in Japan and was largely used to receive senior Allied officers and diplomatic dignitaries.

In order to create a befitting ambience, the general had a venerable elderly lady, dressed in an appropriately designed kimono, posted at the front door to open it for his visitors. She performed her simple but important duties with dignity and precision, taking a deep bow without uttering one English word. She asked me what she could say in the English language by way of a welcoming greeting, to which I carefully and precisely instructed her to say, ‘Oh, my bloody back’.

I believe that she blissfully continued doing so to the astonished amusement of the various visitors throughout the general’s occupancy of the residence. I am also certain that he was never made aware of my prank and its outcome before a senior army officer brought it to his notice many years later. He often reminded me of the incident over the years after his retirement, and did so in good humour.

Reproduced from Soldiers’ Tales by kind permission of Denny Neave, Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd

LEARNING TO SURVIVE

PETER BROOKS was in the Royal Australian Army. He has contributed the following story, the second of three from the project In Our Words, an initiative of the State Government of Victoria.

I was 18. A few of us were called out because we weren’t of age, so we did proper training in Japan: 30-mile route marches, assault courses, defusing mines, laying trip-wires and making bridges.

I turned 19 in May ’52. By July ’52, I went to Korea with the 3rd Battalion.

The only thing from training that was any good to me in Korea was learning about mines.

One night my sergeant got wounded. I woke the next morning and my CO made me section leader. I was suddenly responsible for the lives of ten guys.

I said, ‘I’m not good enough to do this.’

The CO said, ‘Yes, you are – you’re experienced.’

I was nervous but I had no option. I was in charge of my section for six months. There were a lot of things to watch out for. I had to make sure we didn’t walk into any minefields. You’re walking on loose ground. First you’d feel it underfoot. Solid: Keep your foot on the mine; dig around to find the fuse and remove it; backpedal out – it’s safe behind you but not in front of you.

There were fighting patrols in which we had a call-and-response password. If they didn’t answer to your password we’d say,

‘Advance and Be Recognised.’

If they didn’t answer again, we’d have to open fire.

I was discharged in 1955 – I was 22. I couldn’t settle down when I came back. I never used to drink or smoke before I was in Korea. I couldn’t handle civilian life. I got work on a fishing boat in Western Australia. Being on the fishing boat helped. There were three Norwegian fishermen who gave me some good advice. They said I’d be better off re-joining the forces.

So I did.

I joined the Air Force, air and sea rescue. After six months of intensive training I was confident I could do the job.

My wife said that I’d settled down after joining the Air Force.

Normal life just wasn’t exciting.

A PROMISE TO A MATE

VICTOR DEY was in the Royal Australian Army in Korea and has contributed the following story, the last of three stories from the project In Our Words