Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

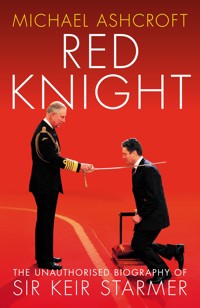

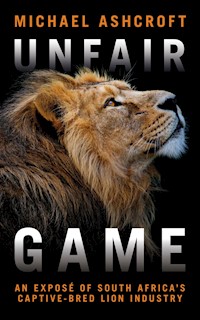

In April 2019 Lord Ashcroft published the results of his year-long investigation into South Africa's captive-bred lion industry. Over eleven pages of a single edition of the Mail on Sunday he showed why this sickening trade, which involves appalling cruelty to the 'King of the Savannah' from birth to death, has become a stain on the country. Unfair Game, to be published in June 2020, features the shocking results of a new inquiry Lord Ashcroft has conducted into South Africa's lion business. In the book, he shows how tourists are unwittingly being used to support the abuse of lions; he details how lions are being tranquilised and then hunted in enclosed spaces; he urges the British government to ban the import of captive-bred lion trophies; and he demonstrates why Asia's insatiable appetite for lion bones has become a multimillion-dollar business linked to criminality and corruption, which now underpins South Africa's captive lion industry.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 408

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

‘Until the lion tells the story, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.’

african proverb

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have assisted with this project, but it is a shocking indictment of South Africa’s lion industry that some of them must remain nameless for security reasons. The threats and intimidation that are rife in lion farming, canned hunting and the bone trade make it unwise to name every individual linked to this book.

Those who have been notably generous with their time are Dr Andrew Muir, Ian Michler, Dr Don Pinnock, Colin Bell, Linda Park, Amy P. Wilson, Eduardo Goncalves, Kevin Dutton, Stewart Dorrington, Stan Burger, Gareth Patterson, Beth Jennings, Nikki Sutherland, Richard Peirce, Iris Ho, Doug Wolhuter, Dr Peter Caldwell, Dr Pieter Kat, Adrian Gardiner, Christine Macsween and Karen Trendler. None of these individuals was aware of my undercover investigation and, despite their cooperation, some will not share my views as detailed in this book.

Thanks must also go to my corporate communications director, Angela Entwistle, and her team, as well as to those at Biteback Publishing who were involved in the production of this book.x

Special thanks to all the undercover operatives who carried out their assignments with courage and professionalism. The Born Free Foundation and South Africa’s National Council of Societies for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (NSPCA) were also immensely helpful.

And special thanks go to my chief researcher, Miles Goslett, for his outstanding editorial support.

FOREWORD

BY SIR RANULPH FIENNES

Africa holds a special place in my heart. It is where I grew up and learned about the wonder of nature. It is also where the British Empire tragically unleashed the plague of persecuting animals purely for pleasure, which has wrought such devastating damage. Trophy hunters continue to travel to Africa to plunder what remains of the populations of some of the greatest animals ever to walk the planet. This includes lions.

Over the past thirty years, South Africa has become a magnet for people from all over the world who wish to kill a lion in a so-called canned hunt. Through this appalling pastime, the country’s captive-bred lion industry has been able to develop, furnishing these alleged ‘hunters’ with their prey. Yet it is now clear that it is highly destructive in many different ways.

What is truly awful is that its wheels are oiled unwittingly by tourists, most of whom pay to spend time with captive-bred lions without realising their true plight. That it also now feeds the bone markets of Asia once the lions are dead is scandalous.

This is a problem for all of us. Humans everywhere share an extraordinary natural heritage. It is therefore the responsibility xiiof everybody to care for it. Britain may have played a major role in the many crises faced by animals today. We can certainly play a leading role in coming up with some solutions. With this in mind, Lord Ashcroft’s investigation of the captive-bred lion industry is timely and I welcome it wholeheartedly.

Sir David Attenborough once said that humans must ‘step back and remember we have no greater right to be here than any other animal’. Wildlife is not a resource that we can exploit with no regard for its well-being. We debase ourselves when we consciously ignore the pain and suffering we inflict and then give weasel-worded justifications for what is plainly wrong and immoral. We are the planet’s most powerful species. That places upon us a special responsibility to treat all living things with respect.

It is also our responsibility to hand over the baton to the next generation with South Africa’s captive-bred lion industry consigned firmly and permanently to the dustbin of history. I hope sincerely that this book will go a long way towards helping to do just that.

AUTHOR’S ROYALTIES

Lord Ashcroft is donating all royalties from Unfair Game to wildlife charities in South Africa.xiv

INTRODUCTION

In December 2018, I went to South Africa to report on Footprints of Hope, a unique project arranged by a British charity that aims to combat wildlife crime. Footprints of Hope allows veterans suffering from physical and mental health problems to spend time caring for orphaned baby rhinos. Dozens of these creatures, some only weeks or months old, are found abandoned in Africa every year. In almost all cases their mothers have been brutally shot and dehorned, sometimes while they are still alive, by poachers.

The programme was hosted by a second charity, Care for Wild, whose sanctuary just outside South Africa’s famous Kruger National Park has become a home for many rhinos. The aim of Footprints of Hope is for humans and animals, both damaged by traumatic events in their lives, to benefit from the other’s existence through animal-assisted therapy (AAT), which brings animals and humans together. AAT is used to complement and enhance the benefits of more conventional therapy. Through my sponsorship of Footprints of Hope, five UK Armed Forces veterans have so far benefited from this project.

While I was planning this trip, I decided I wanted to spend xvisome of my time in South Africa making enquiries about another imperilled creature: the lion. I was familiar with the ghastly phenomenon of so-called canned lion hunting, in which wealthy tourists pay tens of thousands of dollars to ‘hunt’ a lion when in reality all they do is pursue a tame creature in an enclosed space and then shoot it. I was also aware that hundreds of lions die in this manner in South Africa each year. As I detest animal maltreatment, I wanted to find out more about this particular form of cruelty so that I might be able to help end it.

As I journeyed around the country, I spoke to many animal experts and conservationists and listened to what they had to say. What I heard shocked me. It soon became clear that, however abhorrent canned lion hunting undoubtedly is, it represents just one element of a far greater problem. It is no exaggeration to say that the abuse of lions in South Africa has become an industry. Thousands are bred on farms every year; they are torn away from their mothers when just days old, used as pawns in the tourist sector, and then either killed in a ‘hunt’ or simply slaughtered for their bones and other body parts, which are very valuable in the Asian ‘medicine’ market. In between, they are poorly fed, kept in cramped and unhygienic conditions, beaten if they do not ‘perform’ for paying customers, and drugged.

This sinister system has sprouted up in plain sight in South Africa, inflicting misery on the ‘king of the savannah’ on an unimaginable scale. My research suggests it is highly likely that there are now at least 12,000 captive-bred lions in the country, against a wild population of just 3,000. Yet, strikingly, just a small number of people – a few hundred – profit from this abusive set-up. Thanks to South Africa’s constitution and laws, they xviiseem to be able to operate as they wish. In a country so vast, it is easy to see how anybody with the means to do so can break into this ugly business. What many will not realise, though, is that the lion trade is inextricably linked with violent international criminal networks. It could hardly be more sinister.

The harrowing details that I picked up during that visit in 2018 forced me to see just how desperate the situation has become. As I have learned more about the grim life cycle faced by any captive lion in South Africa, I have become determined to do whatever I can to bring to an end the abysmal industry in which these animals are caught. Quite apart from the harm inflicted upon the creatures themselves, their rampant exploitation is a stain on a country that I love. Indeed, it is a stain on all of us.

It is clear to me that the overwhelming majority of South Africans and, I would happily bet, citizens everywhere feel just as strongly as I do about this disgraceful situation. For all of these reasons, I decided to launch two undercover investigations into the lion trade. Their results, contained in this book, show clearly why governments all over the world must do everything they can to stamp out this appalling business. By necessity, this book is divided into two sections. First, I explain how South Africa finds itself in the unenviable position of being at the centre of the world’s lion trade. The second part covers the covert operations.

It is important to acknowledge at the outset of this exposé that the trade in exotic wildlife which is so popular in Asia is believed to have triggered the outbreak in December 2019 of Covid-19, also known as coronavirus. This disease has killed hundreds of thousands of people around the world and, at the xviiitime of writing, the full extent of its effects on public health and on the global economy remains unknown. Lion bones from animals which are bred in captivity in South Africa and are then slaughtered there represent a significant part of this trade because of their value to the so-called traditional medicine market. As this book explains, lions and their bones can carry tuberculosis, among other potentially serious infectious diseases. According to the World Health Organization, TB was responsible for 1.5 million deaths in 2018. Several experts have told me of their belief that by continuing to trade in lion bones, those involved in South Africa’s captive-lion industry are increasing the likelihood of sparking another major public health crisis. It could be a surge in TB, or it might be a rise in another infectious disease which spreads from animals to humans, such as brucellosis. Indeed, like Covid-19, it could be a new disease altogether. As a result of this alarming theory, it must be hoped that if anything positive is to emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic, it will be a severe crackdown on the lion bone trade. Certainly, it is the case that everybody who reads this book will understand that this warning has been made loudly and clearly. As it is, the South African government must be held to account for enabling this set of circumstances to develop as it has done. Should a health crisis ensue, South Africa would be lambasted internationally – something it and its people can ill afford.

Nobody should be in any doubt about the fact that South Africa now stands at a crossroads. There are many difficult decisions ahead, but it is imperative that everybody – especially tourists and hunters – does their bit to ensure that the rank abuse of lions is stopped immediately.

PART I

CHAPTER 1

DEAD CERT

Animals have always been exploited in South Africa. Hundreds of thousands of years ago, primitive man responded to his survival instincts by roaming the Highveld in search of meat. Later, the hunter-gatherer San, who have inhabited the country for at least 20,000 years, developed a formidable reputation for tracking and then killing large mammals including giraffes with bows and arrows. Later still, the Nguni, who settled in the Transvaal region from about 1500, became adept at dispatching lions and elephants for a range of purposes using spears and dogs.

The Portuguese were the earliest Europeans to reach South Africa, in 1488. Although they would shoot and eat smaller prey such as antelopes, it was not until after 1652, when the first Dutch settlement was recorded at Table Bay in Cape Town, that the immigrant population began to disturb the relative harmony in which man and beast had lived up until that point. Majestic predators like the Cape lion, a slightly less bulky subspecies of lion whose natural habitat was concentrated in the mountainous Cape Town area, faced a new threat for reasons which had nothing to do with being turned into food or clothing. They 4were culled in order to protect the Dutch incomers and their farmers’ livestock.

As Dutch power in South Africa receded during the late eighteenth century, the British filled the void, settling in the Eastern Cape from 1820. Their arrival marked a radical turning point in man’s relationship with nature in South Africa. For while excited explorers and zoologists were treated to a seemingly endless supply of unusual creatures to discover and chart for educational purposes, some of their countrymen introduced to the vast new colony the concept of killing animals for pleasure, rather than for ritual or survival. Just as hunting parties were a regular fixture in the social calendars of the ruling classes in Victorian and Edwardian Britain and Europe, so they became in South Africa’s interior. The recreational pursuits of adventurers and professional hunters including Henry Hartley, Sir William Cornwallis Harris, Frederick Selous, Petrus Jacobs and the elephant stalker known intriguingly as ‘Cigar’ ensured the grassy veld came to be regarded as the best game-hunting territory on the continent. Then, as now, male lions were considered more desirable than lionesses. Their manes, a sign of strength and overall health, have always been eminently valuable.

As well as quenching a bloodthirst, there was also a romanticism attached to the idea of the heroic white man taming this sometimes hostile environment by slaying feral brutes. The numerous photographs taken in the nineteenth century in which early modern hunters can be seen posing with their trophies bear witness to this sense of swagger. South African environmental author and academic Dr Don Pinnock says: 5

Originally, the colonial process was to explore wild and wonderful countries and to bring the word of God. The original explorers were biologists. They were very good environmentalists. They were very good artists. They brought back to Britain and Germany and France these beautiful pictures of these wonderful, exotic creatures. If you were living in Europe and you wanted to be a hunter, you would probably hunt grouse. But in South Africa, you could take down ten elephants and be the hero of your own mirror. The local people were aghast. They couldn’t believe so many animals were being killed at once. There were so many, they were left rotting. They’d cut the face off an elephant and leave the carcass. So in those early colonial days there was a mixture of bravado and exploration when it came to man’s relationship with animals.1

Sport was not the only reason that animals were killed in massive numbers throughout the 1800s in South Africa. Armed with increasingly reliable rifles, professional hunters were also able to furnish merchants with the skins, hides, horns and feathers that they would in turn sell to fashionable Europeans who wished to display them in their houses or on their clothes. One hunter, M. J. Koekemoer, apparently boasted of shooting 108 lions in a year in South Africa in the 1870s. If Koekemoer really was capable of such a feat, it should not come as a surprise to learn that more than a decade earlier, in 1858, the aforementioned Cape lion was declared extinct. An entire subspecies of this carnivore was simply shot out of existence.

6Trophy hunting in South Africa continued after the country had gained full independence from the British in 1931, remaining popular among tourists. As time wore on, however, hunting lions undoubtedly became more cumbersome. For one thing, their numbers across the African continent fell markedly thanks to increased poaching. Furthermore, human population growth resulted in the destruction of their habitat. In 1980, there are thought to have been about 80,000 wild lions in Africa. Today, there are an estimated 20,000 wild lions, 3,000 of which are in South Africa. The majority of the others are to be found in Zimbabwe, Botswana, Tanzania and Kenya. Indeed, lions are now extinct in twenty-six countries across Africa and are listed as ‘vulnerable’ on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species. Towards the end of the twentieth century, this sharp decrease had a profound effect on hunting, according to Stewart Dorrington, the president of Custodians of Professional Hunting and Conservation South Africa. He believes that the expense of undertaking a traditional hunt from this point on ‘started going through the roof’.2 Those involved in the hunting industry in South Africa found themselves open to the idea of adapting.

It was under these conditions that the disturbing phenomenon known as ‘canned’ lion hunting began to take root. The origins of this term are still debated, but what this undesirable extension of trophy hunting entails is simple enough to explain. A lion – usually, but not exclusively, one which has been raised in captivity – is released into a fenced enclosure ranging 7in size from an acre to several hundred acres. This means it is unfairly prevented from escaping its hunter, who is often positioned advantageously on the back of an open-top vehicle. It is then killed, probably at close range. Unlike in traditional or ‘fair chase’ hunting, in which animals might be pursued cross-country for up to three weeks with no guaranteed outcome, the canned hunted lion faces certain death perhaps within hours, seemingly for nothing more than the amusement of the hunter. Sometimes, the animal is drugged before the hunt takes place in order to move it more easily to the contained area where it will meet its end. As it is likely to suffer the physical effects of any such tranquilliser for many hours, its wooziness cements further the pathetic inevitability of its plight. In canned hunting, the balance of power is tilted so heavily away from the quarry and in favour of the stalker that it is absurd for it to be considered in any way an honest contest. Indeed, it seems most appropriate to use the phrase ‘shooting fish in a barrel’. Tenacity and skill come a distant second to securing the instant gratification of a quick hit.

The history of canned hunting in South Africa is not definitively known, almost certainly as a result of it initially being kept underground through being such a squalid activity, but the country is now considered to be its global centre. Gareth Patterson is a South Africa-based environmentalist who in 1989 rehabilitated three young lions which had previously been in the care of his murdered friend George Adamson, the naturalist whose wife Joy wrote the book Born Free about raising a lion cub. Having investigated canned lion hunting himself, Patterson believes it was imported to South Africa. ‘Its origins are 8North American and it was brought over here,’ he says. ‘One of my contacts told me she witnessed a canned hunt involving a lion on one of the private reserves adjoining the Kruger National Park way back in 1976, but it is not clear how common it was at that time.’ He believes it was probably not until the late 1980s that it became more firmly embedded in South Africa.3

A report published in the Dallas Morning News on 1 May 1988 under the headline ‘Tame Lions Shot for Sport’ details a canned hunt which took place on a Texas ranch owned by a Mr Larry Wilburn. If this was not the first time that this phrase had been used in the media, it is certainly one of the earliest known examples, and the tone of this article suggests the term only entered the mainstream in America around then. ‘“Canned” lion hunts have become quietly popular in recent months,’ the report states, with Wilburn revealing that he had been involved in this burgeoning venture for about two years and was paid $3,500 (equivalent to $7,700 in 2020) by each client to shoot a lion. ‘We threw rocks in to spook [the lion] out and he charged us at that point,’ Wilburn was quoted as saying. ‘We killed him at 10 feet away.’ He added that he had a waiting list of eager trophy seekers who were happy to take part in a staged lion hunt because they ‘don’t want the trouble of going to Africa’.

According to Patterson, the first documented evidence in South Africa of domestic canned hunting came in the summer of 1990, when a report was published in The Star, a Johannesburg-based newspaper. Under the headline ‘R20,000 for a “Canned” Lion – Wrangle as Old Circus Animals Let Loose for Trophy 9Hunters’, this news story revealed that retired circus and zoo animals were being released onto farmland in the Eastern Cape for the explicit purpose of being shot by trophy hunters, explaining, ‘but before they pay up to what is believed to be about R20,000 for what some hunters refer to as “canned lions”, they have to sign a form stating they are fully aware that the lions come from a circus, zoo or lion park’. It continued: ‘They [the hunters] know it will not be a wild animal [they are hunting] but a lion that was once hand reared as a cuddly cub, destined to die for the gratification of man.’4

Public outrage at this new craze followed, with a petition signed by hundreds sent to the Department of Nature Conservation (now the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries). It was only through this lobbying exercise that it came to be understood firstly that hunting a lion which has been born and bred in captivity was not illegal in South Africa, and second that no legal definition for canned hunting existed. Astonishingly, this remains the case today.

Throughout the 1990s, the number of lions held in captivity in South Africa for the purpose of being subjected to a canned hunt was comparatively low, being in the hundreds. By 2005, its popularity had soared, and there were an estimated 2,500 non-wild lions in South Africa.5 As a result, attempts were made under the administration of President Thabo Mbeki to both define and regulate canned hunting. This included 10introducing regulations in the relevant environmental legislation, the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act of 2004 (NEMBA), and the Threatened or Protected Species Regulations of 2007 (TOPS). These moves were challenged in the courts by powerful pro-hunting groups, however, notably the organisation now known as the South African Predator Association (SAPA). SAPA’s influence on successive South African governments has never been in doubt. Among its arguments were suggestions that the regulations had not been properly researched. It also raised as a concern the potential economic impact of the proposed regulations on those involved in the lion industry. The case made its way to South Africa’s highest court of appeal, which in 2010 essentially found in favour of the hunting industry. Insofar as some of the NEMBA and TOPS regulations related to lions, they were set aside, allowing the status quo to continue. And so, while there are certain restrictions in law as to the manner in which lions may be hunted, there is no strict legal definition of canned hunting in South Africa. Neither is there any direct prohibition of it.

Two primary legal circumstances have allowed canned hunting to continue. Firstly, South African law classes all wildlife generally speaking as the property of the person on whose land the animals live, meaning that landowners are effectively free to do as they wish with those animals, subject to certain exceptions. Second, the ‘right to environment’ provision enshrined in South Africa’s supreme constitution allows for the ‘sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development’. In other words, using animals for commercial gain is deemed acceptable, as 11long as over-exploitation is avoided. Disastrously, though, this privilege has been interpreted in such a way that has to all intents and purposes ensured, and even promoted, lions’ ill treatment. So bastardised has the well-meaning concept become that many in South Africa now joke about ‘sustainable abuse’ rather than sustainable use.

Currently, canned hunters are willing to pay anything from $3,000 to more than $40,000 to shoot a male lion in South Africa, depending on its size and the quality of its mane and skin. According to Four Paws, the international animal rights organisation, between 600 and 1,000 lions are killed in canned hunts in South Africa annually. Exactly thirty years after this inhumane ‘sport’ became known about more widely, the digital age offers hunters an even simpler way to take part in it. Wealthy clients, many of whom have little hunting experience and may be a poor shot, are emailed brochures by hunting companies with photographs of available game. Rather like a customer at a drive-through hamburger restaurant, they place their order before, eventually, pulling the trigger or firing their crossbow.

In 2016, safari cameraman Derek Gobbett made public some deeply unpleasant canned hunting footage taken on a property owned by a firm called De Klerk Safaris in Wilzenau in North West Province. It remains unclear to what extent the owners of this property were involved in organising, as opposed to merely hosting, this ‘hunt’. Gobbett had filmed it at the request of a group of American hunters four years previously who wished to keep it as a souvenir. Yet he remained so appalled by what he witnessed that he leaked the film to draw attention to this debased form of hunting. Through this, the names of the nine 12hunters involved then became known. It is worth describing the footage briefly in order to illustrate what a lion might face when it is subjected to a canned hunt.

In Gobbett’s recording, one large lion with an impressive dark mane which has been released into an enclosure is seen padding slowly past the hunting party without a care in the world. It pauses after being whistled at by one of the hunt’s organisers. This makes it an even easier target than it might otherwise be and confirms that, far from being a wild animal, it was in fact used to interacting with humans. The impact of the first bullet, fired into its front leg at close range from a jeep despite it being illegal in South Africa to shoot an animal from a vehicle, makes it leap into the air. It then rolls forward, gets up awkwardly, and reels for a few seconds in confused agony as though on hot bricks. As it scampers off on three legs to hide in the bush, the guide shouts to his client, ‘Shoot him again! Shoot him again!’ The hunter obeys, multiple times. Having killed the animal, he is seen standing over it and saying in a mock-feeble voice, ‘Hey you, I’m sorry, but I wanted you.’ Then, nauseatingly, he kisses the carcass. Another canned kill in the video is a lioness. Terrified after being pursued, she is seen taking refuge in a warthog hole. Eventually, she is shot while underground, also at close range. Once dead, she is dragged into the sunlight by euphoric group members, who are evidently proud. In separate scenes, a second lioness is seen hiding in a tree, showing no sign of wanting to attack the canned hunters, before also being dispatched. Having been shot once, she falls from the tree but becomes stuck on a branch. She is shot again before collapsing onto the ground. 13

The way the men in Gobbett’s film indulged in excited commentary and analysis as mortally wounded animals lay suffering in front of them is striking. It is very hard to understand why they and their guides were unwilling to put dying creatures which had no chance of escape in the first place out of their misery. Once each lion had expired, the kill was marked with sustained laughter, celebratory high-fives, gleeful handshakes or slaps on the back – acts of jubilation that simply were not warranted given the relative simplicity of each target.

If anything positive is to be learned from the canned hunting recorded by Gobbett, it is that the tourists were tricked. Gobbett made clear that the hunt organisers drove their clients around the compound for hours pretending to track what they claimed were dangerous wild animals when in reality they knew that this contained space had been filled with a known number of relatively tame specimens that could be found without much struggle. They elongated the exercise because they were fearful that an activity they had promised would last for days would be over in a matter of hours because it was just too easy. The hunters were named as Peter Campisi, Antonio Tantillo, Jack Dellorusso, Victor Como, Armond Mkhitarian, Pete Louloudis, Carmine Marranzine, Bob Vitro and Frank Gagliardo. It is hard to know who is the more pathetic: these men who were duped out of thousands of dollars and who naively believed they were taken on a proper hunting trip, or the lions whose fates they sealed.

In fact, the first principal alarm to be sounded alerting people outside South Africa to the fact that its lions were being maltreated came almost twenty years before Gobbett’s footage 14surfaced, in May 1997, when a documentary made by the British investigative journalist Roger Cook titled Making a Killing was broadcast in the UK. It was considered so shocking that a South African current affairs TV programme, Carte Blanche, also broadcast it shortly afterwards in order to inform the country’s own people of this sick pastime. Quite apart from telling millions about canned hunting, Making a Killing also hinted at the scale of the abuse of lions in South Africa and showed that those involved in this twisted business were willing to threaten human lives in order to protect their commercial interests.

In the undercover film, part of the long-running ITV series The Cook Report, the redoubtable Cook posed as a businessman who was willing to pay $18,000 to take part in a canned trophy hunt on the remote Mokwalo Game Farm in Limpopo Province, the furthest north in South Africa, run by husband-and-wife team Sandy and Tracy McDonald. Sandy McDonald bragged to Cook that his company, then called McDonald Pro Hunting, had killed more than 1,000 lions in 1996 alone. He advised his ‘client’ that his ‘kill shot’ should be fired into the lion’s leg or under its chin in order to keep its head unblemished so that it would make a decent trophy. This tactic, of course, makes the animal’s death slower and more painful.

Regrettably, the master copy of this film was lost in a fire and no known recordings survive, but Cook later recalled in print his experience of canned lion hunting. He wrote:

I soon realised we were driving around in circles, but they wanted to make it look good, as if it was a real hunt. We eventually came across our lion, apparently asleep under a 15tree. I had a professional cameraman with me, ostensibly making a vanity video. The jeep was bristling with weapons – including the one I was supposed to use, a heavy-calibre Remington hunting rifle. When McDonald told me it was time to use it, I refused, telling him the canned hunting of such a helpless animal was at best immoral, and that I was not a rich businessman but a television reporter. We were then driven at speed back to camp where a very angry McDonald and friends demanded that we hand over our tapes. However, in the interim, we had taken the precaution of concealing our evidence in the upholstery of our minibus. We then palmed them off with blank tapes. Had we not given up what they thought was our evidence, said one of McDonald’s men, we would have been involved in an unfortunate fatal shooting accident.6

It is worth observing that the McDonald family is still in business, the company website proudly advertising that three generations of McDonalds have provided hunting opportunities to paying customers since 1953.

Cook’s film certainly made an impact, winning the Brigitte Bardot International Award for best wildlife investigation of 1997 at the annual Ark Awards. It also inspired the South African environmental journalist and safari operator Ian Michler, whose eyes were at that time beginning to be opened to the many unpleasant consequences of this activity. He had first heard about canned hunting earlier in the 1990s. Since then, he 16has devoted more than twenty-five years to investigating and exposing the ruthless exploitation of lions in his country, and his work has rightly earned him a reputation in conservation circles as a pioneer. His 2015 documentary Blood Lions shone a powerful light on this uncomfortable subject. Michler says he first stumbled upon canned hunting by chance. ‘I used to live in Botswana,’ he says.

I ended up as a co-owner of a lodge and also assisted great friends at their horseback operation in the Okavango, and out of the hunting season we would hear gunshots going off and sometimes light aircraft taking off or landing on this little air strip which wasn’t far from where our horse riding camp was. Very soon I found a link between professional hunters – fair chase hunters operating in the Okavango – and one of our provinces here in South Africa, the Free State, which at the time I discovered was a centre for canned hunting. That was the first time I was exposed to this link. Clients who came to the Okavango to hunt lions but who couldn’t bag one were sometimes flown to South Africa afterwards to take part in a canned hunt. And this information was given to me by pilots who were flying these charter aeroplanes. That was when I started piecing together the notion that you could go from a two-week fair chase hunt to a one- or two-day canned hunt. When the Cook Report came out, I would dare to say it was the first time most people in South Africa and in the world gained an understanding that animals were being shot in these very confined spaces. But people in general didn’t really have an understanding of how the whole industry was going 17to turn out. After that, I intensified my research. I started writing about it.7

What soon became clear to Michler was that canned hunting operations were able to flourish in South Africa thanks to the country’s private property laws and were bolstered by the Game Theft Act 1991, a piece of legislation introduced during the apartheid era which regulates the ownership of game. Michler says:

In South Africa, unlike in most of Africa, we have private land laws, so you have title deeds. The law is simple: you can do on your land what you want to do. If you have a wild animal on your land, you have ownership of that wild animal in the same way farmers own livestock. The leap in canned hunting came when someone said: ‘This is commercially possible as a revenue stream.’ That was probably in the late ’90s.

Indeed, he adds, it is frighteningly easy to become a canned hunt operator if you have access to private land. ‘You have to have a two-metre-tall fence that’s double stranded and electrified. That’s it. You’re supposed to submit an Environmental Impact Assessment to the authorities. Some people do, some don’t.’

There is one further aspect of this barbaric transformation of traditional hunting that makes it quite distinct from what went before: breeding. After a time, the animals that were being 18offered up to canned hunters were not just those that had been sold to farmers by circuses and zoos. As shall become clear, they were born and reared in captivity for the ultimate purpose of being killed – literally, bred for the bullet. Michler says:

With hindsight, when I look back to some of the farmers I spent time with in the late ’90s and early 2000s, one individual particularly used to take me around his property and tell me what his plan was. He would say, ‘I can make a fortune.’ He wanted to use elephants. He wanted to put hunters on the backs of elephants to go and shoot lions that he’d bred in cages. He showed me the whole layout. Commercially, the mid- to late 1990s was when canned hunting started taking hold.

In his capacity as a professional hunter who is anti-canned lion hunting, Stewart Dorrington agrees with Michler’s analysis. He says:

I had been a professional hunter since 1988 and the first time [canned hunting] came to my notice was the exposé of the Cook Report. The industry grew because there were limited wild lions to hunt and those were, and still are, very expensive. As the number of wild lions available to hunters declined, mostly due to bad management by governments and also because of habitat loss, so the demand to shoot a captive-bred lion increased. In the early days, most hunters hunting a captive-bred lion had no idea it was captive-bred, as many were sold as ‘problem’ lions or wild lions. However, that has changed as far as I know, and hunters know they are shooting 19a captive-bred lion and there is still a demand for it, much like there is a demand for shooting bred pheasants in the UK.8

Having established that canned hunting is an especially cruel way of killing a lion, the important question arises of what kind of person would facilitate this form of so-called entertainment. Michler is in no doubt about the answer. He believes that canned hunting, together with every other element of the lion farming industry in South Africa that has grown up around it, is dominated by the country’s white population. Some of them, he thinks, have not moved on mentally from the days of apartheid despite its legal apparatus having been abolished thirty years ago. ‘Nearly all of the lion breeders and farmers come out of the apartheid era and they have no respect for human rights,’ Michler says. ‘They supported a doctrine that discriminated against humans. Now you’re asking these same people to have some sort of respect for animal welfare, but it’s not in their lexicon. I challenge you to find a black farmer who’s involved in the lion farming industry.’

Surprisingly, Michler says that religion, particularly the Calvinist beliefs traditionally held by Afrikaans-speaking farmers, may play an important role in the breeders’ and farmers’ outlook as well. ‘There is this conservative, God-fearing sense that man has power over all other species and that “we’re entitled to do this”. It’s strong, and it’s been told to me on these farms.’ He adds that canned hunting itself is also, in his view, an almost exclusively white pastime.

20

I challenge you to find a black trophy hunter who wants to shoot these animals. I’ve run safari operations across sixteen countries. I’ve been writing as a journalist about issues across the continent for thirty years. I don’t know a single ethnic African group that kills animals for fun. They kill for food, for ritual, for ceremonial purposes. But they never kill animals for fun. They don’t go out and shoot five lions. It’s a colonial construct, brought in by the colonials.

His opinion is backed up by research. One academic study published in 2018 examined the attitudes of African people towards trophy hunting, of which canned hunting is now considered an integral part. By sifting the social media posts of 1,070 indigenous citizens, it was concluded that there was overwhelming ‘resentment towards what was viewed as the neo-colonial character of trophy hunting in the way it privileges Western elites in accessing Africa’s wildlife resources’. Most revealingly, the study stated that trophy hunting per se was not considered unacceptable from an animal rights perspective by Africans, but instead ‘as a consequence of its complex historical and postcolonial associations’.9

Due to its opaque status, it is difficult for anybody to be certain how much land in South Africa is used by the predator breeding industry. It is, however, easier to reflect upon the likely consequences of so much land being owned by South Africa’s white population. According to a report produced by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies at the University of the Western Cape and co-authored by Professor Johann Kirsten 21of the University of Stellenbosch, 64.8 million hectares (160 million acres) of farmland in South Africa is owned by white people. The report, which relies on data from 2018 published by the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, states that this amounts to 53 per cent of total land in the country. To put this in context, the latest census, carried out in 2011, found there were 4,586,838 white people living in South Africa. They made up 8.9 per cent of the population. With roughly half of the country’s land therefore being in the hands of less than a tenth of its people, it seems reasonable to conclude that canned hunting and lion farming, both of which rely on the availability of open spaces, almost certainly are businesses controlled by a small portion of South Africa’s white minority.

The desire to derive the maximum return has prompted an increasing number of white farmers and landowners, many of whom have inherited acres from their ancestors, to turn their businesses from livestock or crop farming into the more lucrative trade of exploiting lions for a living. According to Stephen Palos, chief executive of the Confederation of Hunting Associations of South Africa, ‘South Africa has seen some 20 million hectares (50 million acres) of land convert from agriculture to wildlife over about four decades.’10 This phenomenon may even have intensified in recent years given that South Africa’s economy is regarded as one which is underperforming badly.11 Its gross domestic product has declined every year since 2011, when it hit a 22high of $416 billion, and in the spring of 2019, the Daily Maverick online newspaper carried a well-sourced article estimating that one third of the country’s GDP over the previous decade was lost to corruption. With unemployment hovering at 30 per cent and fraud of one kind or another having infected almost every state-run industry, the overall economic picture is frighteningly fragile. Lion farming is considered easier than cattle farming, particularly in the arid areas of North West Province, where most canned hunting takes place and where the terrain is almost like desert. All of these factors help to explain why, over the past decade, hundreds of lion farms have sprung up in the country and the private sector is responsible for managing the largest portion of the lion population in South Africa. It has been estimated that lion breeders contribute the equivalent of $42 million annually to the South African economy by employing farm workers, hunting operators, taxidermists and even slaughterhouse workers.12 With much of the business conducted in cash, however, it would be hard to verify this statistic.

If it is the case that white farmers and landowners have always been the profiteers of what is demonstrably an insidious trade, they cannot have known in the 1990s exactly how that trade was going to develop. Yet, as we shall see, it is undeniable that canned hunting is directly responsible for the growth of even greater evil when it comes to the abuse of lions in South Africa.

1 Interview with Dr Don Pinnock, 2 August 2019

2 Interview with Stewart Dorrington, 6 December 2018

3 Interview with Gareth Patterson, 11 September 2019

4 Quoted in Gareth Patterson, Dying to be Free: The Canned Lion Scandal (Peach Publishing, 2012)

5 Vivienne Williams, David Newton, Andrew Loveridge, David Macdonald, ‘Bones of Contention: An assessment of the South African trade in African Lion Panthera leo bones and other body parts’ (TRAFFIC International and WildCRU, July 2015)

6 Roger Cook, ‘Shooting a lion for fun… What sort of person does that?’, Daily Mirror, 12 August 2019

7 Interview with Ian Michler, 31 July 2019

8 Interview with Stewart Dorrington, 30 September 2019

9 Mucha Mkono, ‘Neo-colonialism and greed: Africans’ views on trophy hunting in social media’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Volume 27 (2019)

10 Letter from Stephen Palos to the Dallas Safari Club, dated 13 January 2018

11 Peet van der Merwe, Melville Saayman, Jauntelle Els and Andrea Saayman, ‘The economic significance of lion breeding operations in the South African Wildlife Industry’, International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation (2017)

12 Ibid.

CHAPTER 2

EXOTIC PLAYTHINGS

South Africa is the only country in the world to classify lions under three categories: wild, managed wild and captive-bred. Wild lions are truly free, living as apex predators in vast national parks and game reserves such as Kruger National Park in the north-east and Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park in the Kalahari desert region. Their close cousins, managed wild lions, are kept in private or government-run fenced reserves typically less than 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) in size and are organised in such a way that their population growth is limited and their genetic integrity preserved. Together, these two groups represent the lions in South Africa that conservationists consider to be of value. The third group, captive-bred lions, is altogether different. It consists of two sub-categories: ‘tourism-bred’ and ‘ranch-bred’. The former are accustomed to humans. The latter are also used to humans, though the South African Predator Association claims they are raised with as little human contact as possible. Not only are captive-bred lions the most populous variety of lion to be found in South Africa but, from the point of view of nature, they are also the most tragic. Ecologists 24believe they have no conservation merit whatsoever because they are highly likely to be genetically tarnished through inbreeding. Furthermore, scientists consider that, having been reared by or around humans, they have in effect been corrupted and for all practical purposes could never survive in the wild.

Professional hunters and adventurers in Victorian and Edwardian-era South Africa might have earned the retrospective outrage of many people for shooting certain species such as the Cape lion to extinction. As is clear, however, having introduced canned lion hunting into the country in the late twentieth century, their modern-day counterparts are responsible for sustaining what is undoubtedly a far more sinister killing system, given its one-sided nature. This dark enterprise is now reliant solely upon the captive-bred lion population.

In order for canned lion hunting to have thrived in South Africa as it has done over the past three decades or more, a sufficient amount of stock has had to exist to meet demand. This has necessitated the commercial breeding of lions in captivity for the explicit purpose of their exploitation. The king of the savannah, revered internationally for generations in heraldry and still to be found on South African banknotes, has been reduced to little more than an organism that rolls off a production line. So rampant has this unregulated business become in recent years, no precise figure exists indicating how many captive-bred lions there are currently in South Africa. Educated estimates, including from the National Council of Societies for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (NSPCA), range 25from 6,000 to 14,000.13 The South African government claims there are ‘more than 6,000 lions in captive breeding facilities across the country’.14 Without question, this means that many thousands of captive lions will have been slaughtered in South Africa since the early 1990s. It also means the number of captive lions dwarfs the existing wild lion population. Indeed, South Africa has the biggest captive cat industry in the world. As shall become clear, although some of these lions are destined to be shot in canned hunts, many more will be killed simply for their bones.