9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

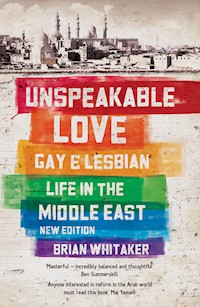

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Homosexuality is a taboo subject in the Arab world. While clerics denounce it as a heinous sin, newspapers write cryptically of 'shameful acts' and 'deviant behaviour'. Amid the calls for reform in the Middle East, homosexuality is one issue that almost everyone in the region would prefer to ignore. In this absorbing account, Guardian journalist Brian Whitaker calls attention to the voices of men and women who are struggling with gay identities in societies where they are marginalised and persecuted by the authorities. He paints a disturbing picture of people who live secretive, fearful lives and who are often jailed, beaten, and ostracised by their families, or sent to be 'cured' by psychiatrists. Deeply informed and engagingly written, Unspeakable Love reveals that - while deeply repressive prejudices and stereotypes still govern much thinking about homosexuality - there are pockets of change and tolerance. This updated edition includes new material covering developments since the book's first publication.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

BRIAN WHITAKER was Middle East editor at the Guardian for seven years and is currently an editor for the newspaper’s Comment is Free website. He is the author of What’s Really Wrong with the Middle East (Saqi Books, 2009). His website, www.al-bab.com, is devoted to Arab culture and politics. Unspeakable Love was shortlisted for the Lambda Literary Award in 2006.

‘A compelling read. It captures with detail and with disturbing accuracy the difficulties and dangers facing lesbians and gay men across the Middle East. It helps us to understand the social pressure, the sense of isolation, the anxiety and fear and trauma. And through it all we glimpse also the possibility of hope, of remarkable courage, and perhaps even in the longer term the chance of a more open and accepting society.’ Lord (Chris) Smith, former UK Secretary of State for Culture

‘It is high time this issue was brought out of the closet once and for all, and afforded a frank and honest discussion. Brian Whitaker’s humane, sophisticated, and deeply rewarding book, Unspeakable Love, does exactly that.’ Ali al-Ahmed, Saudi reform advocate and director of the Gulf Institute, Washington

‘Brian Whitaker has given us a moving analysis of the hidden lives of Arab homosexuals. This genuinely groundbreaking investigation reveals a side of Arab and Muslim culture shrouded by the strictest taboos. Arab societies can no longer contain their cultural, religious, ethnic or sexual diversity within their traditional patriarchal definitions of the public sphere. Anyone interested in reform in the Arab world must read this book.’ Mai Yamani, author of Cradle of Islam: The Hijaz and the Quest for an Arabian Identity

‘I enjoyed and learnt much from Brian Whitaker’s book, which is excellent. It was inspirational to me on the challenges to international law, and the uses of nationalism to suppress dissent within countries.’ Fred Halliday

‘This is an important, timely book, and lucid to boot – a must-read for anyone who believes in human rights.’ Rabih Alameddine, author of Koolaids and I, the Divine: A Novel in First Chapters

‘One major barrier to a broader acceptance of homosexuality is dogma. Whitaker’s book tackles the theological arguments in detail, exploring the thorny issue of whether Islam actually forbids gay love or whether social attitudes are the problem.’ Al-Ahram Weekly

‘Wise and compassionate’ Guardian

‘An extremely well-researched and well-written text that allows us an insight into the lifestyle of the gay and lesbian community in the Middle East … educates, informs and engages the reader from the outset to the last page.’ Sable Magazine

‘Veteran Middle East journalist Brian Whitaker’s groundbreaking book tackles the still taboo issue of homosexuality in the Arab world, the first in any language to do so.’ Time Out Beirut

‘Clearly and engagingly written … gives a good picture of the situation of gay men in Arab countries’ Arabist.com

‘A valuable introduction to the difficulties of being homosexual in the Arab world’ Gay City News

‘Never before has such a comprehensive study of gay civil rights been published … Whitaker organizes this book expertly – information is easily accessible and meticulously footnoted’ The Middle East Gay Journal

‘[An] informative primer on the complex historical, religious, social and legal status of same-sex acts and identities in the Middle East … an illuminating book on an important topic’ Publisher’s Weekly

‘Boldly delves into one of the biggest taboos in modern Muslim societies with subtlety and sensitivity, addressing both Arab reformers and interested Western readers. The book provides fascinating insights into the lives of ordinary gays and lesbians, and how society views and treats them.’ Globe and Mail

‘Strong, condensed, world-weary portrait infused with hope’ Kirkus Reviews

‘With all the reams of Western paper devoted to the study of the Middle East, remarkably little has been said about the status of gay men and lesbians in Arab and Islamic cultures and religious texts. UK journalist Whitaker builds an important first bridge across this gap.’ Out

‘If the great appeal of this book lies in Whitaker’s reportage, it is also valuable politically because it challenges the current climate of political relativism that wants to see homophobia as a religious or cultural issue rather than a political one. Whitaker argues for the universality of sexual rights and for liberty in the Middle East, and against the fashion of apologising for its illiberal climate.’ Democratiya

Brian Whitaker

Unspeakable Love

Gay and Lesbian Life in the Middle East

SAQI

First published 2006 by Saqi Books This new and updated ebook edition published 2011

EBOOK ISBN 978-0-86356-459-8

© Brian Whitaker, 2006 and 2011

The right of Brian Whitaker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

SAQI 26 Westbourne Grove London W2 5RHwww.saqibooks.com

Contents

Introduction

A Note on Terminology

A Question of Honour

In Search of a Rainbow

Images and Realities

Rights and Wrongs

‘Should I Kill Myself?’

Sex and Sensibility

Paths to Reform

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

DEPARTURE GATE, Damascus airport: a young Arab man in jeans, T-shirt and the latest style of trainers is leaving on a flight to London. He passes through final security checks, puts down his bag, takes something out and fiddles furtively in a corner. No, he is not preparing to hijack the plane; he is putting rings in his ears. When he arrives in London the tiny gold rings will become a fashion statement that is un-remarkable and shocks no one, but back home in Damascus it’s different. Arab men, real Arab men, do not wear jewellery in their ears.

This is one small example of the double life that Arabs, especially the younger ones, increasingly lead – of a growing gap between the requirements of society and life as it is actually lived, between keeping up appearances in the name of tradition or respectability and the things people do in private or when away from home.

For many, the pretence of complying with the rules is no more than a minor irritation. Men who like earrings can put them in or take them out at will, but sometimes it’s more complicated. Arab society usually expects women to be virgins when they marry. That doesn’t stop them having sex with boyfriends but it means that when the time comes to marry many of them will have an operation to restore their virginity – and with it their respectability. There is no medical solution, however, when a boy grows up too feminine for the expectations of a macho culture. When he is mocked for his girlish mannerisms but can do nothing to control them, when his family beat him and ostracise him and accuse him of bringing shame upon their household, the result is despair and sometimes tragedy.

This book was inspired – if that is the right word – by an event in 2001 when Egyptian police raided the Queen Boat, a floating night club on the River Nile which was frequented by men attracted to other men. Several dozen were arrested on the boat or later. The arrests, the resulting trial, and the attendant publicity in the Egyptian press (much of it highly fanciful) wrecked numerous lives, all in the name of moral rectitude. It was one of the few recent occasions when homosexuality has attracted widespread public attention from the Arab media.

Some time afterwards, while visiting Cairo as a correspondent for the Guardian newspaper, I met two people intimately connected with the case: a defendant who had since been released and the partner of another defendant who was still in jail. At that stage I was thinking of writing a feature article, but later I met a young Egyptian activist (identified as ‘Salim’ elsewhere in this book). As we chatted over lunch, our conversation moved on from the Queen Boat case to questions of homosexuality in the wider Arab world. He seemed very knowledgeable and I remarked casually: ‘You should write a book about it.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘You should write one.’

I mulled this over for several months. It was clearly time for someone to raise the issue in a serious way but, as Salim had indicated, it was difficult for Arabs – at least those living in the region – to do so. Foreign correspondents such as myself often write books about the Middle East, though they tend to be about wars or the big, newsworthy events: Palestine, Iraq, and so on. I had no desire to follow that well-worn path, but this was one topic that would break new ground as well as some long-standing taboos. Homosexuality was a subject that Arabs, even reform-minded Arabs, were generally reluctant to discuss. If mentioned at all, it was treated as a subject for ribald laughter or (more often) as a foul, unnatural, repulsive, un-Islamic, Western perversion. Since almost everyone agreed on that, there was no debate – which was one very good reason for writing about it.

My primary concern in this book is with the Arab countries (though it also includes some discussion of Iran and Israel) but to try to give a country-by-country picture would be both impractical and repetitive. Instead, I wanted to highlight the issues that are faced throughout the region, to a greater or lesser degree, by Arabs whose sexuality does not fit the public concepts of ‘normal’. Most of the face-to-face research was done in Egypt and Lebanon – two countries that provide interesting contrasts. This was supplemented from a variety of other sources including news reports, correspondence by email, articles in magazines and academic journals, discussions published on websites, plus a review of the way homosexuality is treated in the Arabic media, in novels and in films.

One basic issue that I have sought to explain is the reluctance of Arab societies to tolerate homosexuality or even to acknowledge that it exists. This has not always been the case. Historically, Arab societies have been relatively tolerant of sexual diversity – perhaps more so than others. Evidence of their previous tolerance can be found in Arabic literary works, in the accounts of early travellers and the examples of Europeans who settled in Arab countries to escape sexual persecution at home. Despite the more hostile moral climate today, however, same-sex activity continues largely undeterred. This is not quite as paradoxical as it might seem. As with many other things that are forbidden in Arab society, appearances are what count; so long as everyone can pretend that it doesn’t happen, there is no need to do anything stop it. That scarcely amounts to tolerance and the effects, unfortunately, are all too obvious. People whose sexuality does not fit the norm have no legal rights; they are condemned to a life of secrecy, fearing exposure and sometimes blackmail; many are forced into unwanted marriages for the sake of their family’s reputation; there is no redress if they are discriminated against; and agencies providing advice on sexuality and related health matters are virtually non-existent.

A point to be made clear from the outset is that Arabs who engage in same-sex activities do not necessarily regard themselves as gay, lesbian, bisexual, etc. Some do, but many (probably the vast majority) do not. This is partly because the boundaries of sexuality are less clearly defined than in the West but also because Arab society is more concerned with sexual acts than sexual orientations or identities. Although it is generally accepted in many parts of the world that sexual orientation is neither a conscious choice nor anything that can be changed voluntarily, this idea has not yet taken hold in Arab countries – with the result that homosexuality tends to be viewed either as wilfully perverse behaviour or as a symptom of mental illness, and dealt with accordingly.

A further complication in the Middle East is that attitudes towards homosexuality (along with women’s rights and human rights in general) have become entangled in international politics, forming yet another barrier to social progress. Cultural protectionism is one way of opposing Western policies that are viewed as domineering, imperialistic, etc, and so exaggerated images of a licentious West, characterised in the popular imagination by female nudity and male homosexuality, are countered by invoking a supposedly traditional Arab morality.

To portray such attitudes as collective homophobia misses the mark, however. They are part of the overall fabric and cannot be addressed in isolation: they are intimately linked to other issues – political, social, religious and cultural – that must all be confronted if there is ever to be genuine reform. One of the core arguments of this book, therefore, is that sexual rights are not only a basic element of human rights but should have an integral part in moves towards Arab reform, too. Open discussion of sexuality can also bring other reform-related issues into sharper focus.

Many of the Arabs that I interviewed were deeply pessimistic about the likelihood of significant change, though personally I have always been more hopeful. In countries where sexual diversity is now tolerated and respected the prospects must have looked similarly bleak in the past. The denunciations of sexual non-conformity emanating from the Arab world today are also uncannily similar, in both their tone and their arguments, to those that were heard in other places years ago … and ultimately rejected.

Unspeakable Love was first published in 2006. Since then, I have continued following developments in the Middle East and this second edition brings the picture up to date. Unfortunately, I cannot say that the situation on the ground has improved much, though there seems to be more recognition that homosexuality does exist in the Arab countries – which is a start. Where opportunities have arisen, gay and lesbian Arabs have become more visible and assertive, with some of them writing blogs. Several new publications have appeared, either in print or on the internet, and the number of Arab LGBT organisations has grown – though with the exception of Lebanon they still tend to be based outside their home countries.

Many people have helped with this work by offering their time for discussions, providing contacts, reading drafts of the text and suggesting improvements. For obvious reasons, most would prefer not to be thanked by name but I am grateful to them all, nonetheless.

Since the main object of this book is to stimulate debate, readers who wish to take part in further discussion can do so by visiting the relevant section of my website, www.al-bab.com/unspeakablelove. The footnotes are also available there in an online version which provides easy access to web pages mentioned in the text.

I might add, for the benefit of any readers whose native language is not English, that Unspeakable Love is also available in Arabic (Al-Hubb al-Mamnu’a) published by Dar al Saqi and from other publishers in French (Parias: gays et lesbiennes dans le monde arabe), Italian (L’amore che non si puo dire), Spanish (Amor sin nombre) and Swedish (Onämnbar Kärlek).

Brian Whitaker

March 2011

A Note on Terminology

One of the problems when writing about same-sex issues is choosing terminology that is accurate and acceptable to the people concerned but does not become too cumbersome when used repeatedly. Many English-language newspapers treat ‘gay’ and ‘homosexual’ as more or less interchangeable. The style guide of The Times newspaper advises that ‘gay’ is ‘now fully acceptable as a synonym for homosexual or lesbian’, while the Guardian says ‘gay’ is ‘synonymous with homosexual, and on the whole preferable’. Guidelines issued by the BBC for its broadcasters in August 2002 state:

Some people believe the word ‘homosexual’ has negative overtones, even that it is demeaning. Most homosexual men and women prefer the words ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’. Either word is acceptable as an alternative to homosexual, but ‘gay’ should be used only as an adjective. ‘Gay’ as a noun – ‘gays gathered for a demonstration’ – is not acceptable. If you wish to use homosexual, as adjective or noun, do so. It is also useful, as it applies to men and women.

In the context of Arab and Islamic societies, however, proper use of ‘gay’ is more complicated. The word carries connotations of a certain lifestyle (as found among gay people in the West) and it implies a sexual identity that people may not personally adopt. ‘Homosexual’ – describing a person – may not have the same westernised connotations but can be equally inappropriate, especially where homosexual acts are an occasional alternative to those with the opposite sex.

Arabic itself has no generally-accepted equivalent of the word ‘gay’. The term for ‘homosexuality’ (al-mithliyya al-jinsiyya – literally: ‘sexual same-ness’) is of recent coinage but is increasingly adopted by serious newspapers and in academic articles. The related word mithli is beginning to be used for ‘gay’ or ‘homosexual’. Meanwhile, the popular media continue to use the heavily-loaded shaadh (‘queer’, ‘pervert’, ‘deviant’). The traditional word for ‘lesbian’ is suhaaqiyya, though some argue that this has negative connotations and prefer mithliyya (the feminine of mithli). Arabs also have a variety of more-or-less insulting words for sexual types (e.g. effeminate men) and those who favour certain kinds of sexual act. Arabic terminology is discussed more fully in Chapter Seven.

For the purposes of this book, the following English usage has been adopted:

Homosexuality: Acts and feelings of a sexual nature between people of the same gender, whether male or female, and whether or not the people involved regard themselves as gay, lesbian, etc.

Homosexual: Behaviour, feelings, practices, etc, directed towards people of the same gender. It is used adjectivally in the text but not as a noun (e.g. ‘a homosexual’).

Lesbian: Applied to women who have adopted this as their sexual identity.

Gay: Applied to men who have adopted this as their sexual identity. In some contexts (e.g. ‘gay community’) the term should be regarded as shorthand which includes various other non-heterosexual identities: lesbian, bisexual, transgender, etc.

Gay rights: A shorthand way of referring to all sexual rights of a non-heterosexual nature. Not restricted to gay men.

Transgender: Refers to people who for physical or psychological reasons do not consider they belong to the gender originally assigned to them.

The usage outlined above applies to the author’s text; quotations reproduced within the text may contain different usages.

ONE

A Question of Honour

FACED WITH THE PROBLEM of a son who shows no interest in girls, the first instinct of many Arab parents is to seek medical help. Salim was twenty when his family asked if he was gay. He said yes, and they bundled him off to see the head of psychiatry at one of Egypt’s leading universities. Salim told the professor that he had read about homosexuality and knew it wasn’t a mental illness, but the professor disagreed. ‘An illness,’ he replied, ‘is any deviation from normality.’

The professor offered Salim a course of psychiatric treatment lasting six months. ‘He told me he couldn’t say what the treatment would be until he knew more about my problem,’ Salim said. ‘I asked how he knew it would take six months, and he said that’s what it usually takes. I turned it down.’1

Six months’ psychotherapy may be pointless, but there are far worse alternatives. Stories abound in Egypt and other Arab countries of sons with homosexual tendencies being physically attacked by their families or forced to leave home. Ahmed2 told of a friend whose father discovered he was having a homosexual relationship and, after a beating, sent him to a psychiatrist. ‘The treatment involved showing pictures of men and women, and giving him electric shocks if he looked at the men,’ Ahmed said. ‘After a few weeks of this he persuaded a woman to pretend to be his girlfriend. His father was happy for a while – until he found a text message from the boyfriend on his son’s mobile phone.’ The beatings resumed and the young man fled to the United States.

Ali, still in his late teens, comes from a traditional Shi‘a family in Lebanon and, as he says himself, it’s obvious that he is gay. Before fleeing his family home he suffered abuse from relatives that included hitting him with a chair so hard that it broke, imprisoning him in the house for five days, locking him in the boot of a car, and threatening him with a gun when he was caught wearing his sister’s clothes.3 According to Ali, an older brother told him: ‘I’m not sure you’re gay, but if I find out one day that you are gay, you’re dead. It’s not good for our family and our name.’

A year on, having left home and found a job in a different part of Lebanon, Ali seemed remarkably phlegmatic about his relatives’ behaviour. ‘They are a Lebanese family and they didn’t have enough information about gay life,’ he said. ‘For my dad, being gay is like being a prostitute. He would say: ‘Is someone forcing you to do this?’ My family would ask: ‘Why are you walking like that?’ My sister suggested going to a doctor. She said it’s time to get married and have sons and daughters. I thought something was wrong with me, then I met a guy who told me about gay life and I started to understand myself more.’

The final break came when Ali’s father seized his mobile phone and found gay messages on it. ‘My dad told me I couldn’t go out any more – I had to stay at home 24/24. After two hours I just put all my things in my bag and said I’m leaving. My brother said, “Let him leave, he’s going to come back after a couple of hours.” That was a year ago when I was eighteen. For the first three months I lived with my boyfriend.’

Asked if he thought the conflict with his family was over, Ali replied: ‘No. It will come back when one of my parents dies.’ Out of concern for his safety, friends recorded a detailed statement of his experiences and deposited it with a lawyer. They also urged him to leave the country but he was unable to retrieve the necessary papers from his family’s home in order to get a visa.

The threats directed against Ali by his brother, and the accusation that he was besmirching the family’s name, reflect a concept of ‘honour’ that is found in those parts of the Middle East where old-fashioned social values still prevail. Preserving the family ‘honour’ requires brothers to kill an unmarried sister if she becomes pregnant (even if – as has happened in some cases – her pregnancy is the result of being raped by one of her own family). Although deaths of gay men in ‘honour’ killings have been suspected but not confirmed,4 at least one non-fatal shooting has been recorded.

A Canadian TV documentary highlighted the case of a gay Jordanian, the son of a wealthy politician.5 At the age of twenty-nine he was forced into marriage by his father when rumours spread about his sexuality. The man, identified by the name ‘al-Hussein’, said he had told his fiancée the truth but she went ahead with the marriage because of his family’s social standing. They later had three children by artificial insemination.

Al-Hussein continued to have discreet same-sex relationships but, after ten years of marriage, he fell in love with a member of Jordan’s national judo team, separated from his wife and moved to a house on the outskirts of the capital, Amman, to spend more time with his male lover. One night, his brother saw the two men kissing and pushed al-Hussein down the stairs. He spent three months in hospital recovering from the injuries, with an armed bodyguard outside the door. Later, his brother found him in the hospital lobby following a visit from his lover, and shot him in the leg. His brother, a Jordanian civil servant, was never prosecuted for the attacks because they were considered a family matter.6

On his discharge from hospital, al-Hussein was not allowed back to his own house but became, in effect, a prisoner in his brother’s home, confined to a tiny room with bars on the window. A sympathetic aunt who was living in Toronto persuaded the family to let him join her in Canada and he was eventually allowed to go in return for signing over all his possessions – his house, his interior design business, two cars and his inheritance rights – to the brother who had shot him.

‘I don’t approve of what my brother did,’ al-Hussein told a Canadian newspaper, ‘but I understand why he did it. It was about preserving the family’s honour.’7

* * *

WHETHER A GAY ARAB is considered mad or bad – as a case for psychotherapy or punishment – depends largely on family background. ‘What people know of it, if they know anything, is that it’s like some sort of mental illness,’ said Billy,8 a doctor’s son in his final year of studies at Cairo University. ‘This is the educated part of society – doctors, teachers, engineers, technocrats. Those from a lesser educational background deal with it differently. They think their son was seduced or lured or came under bad influences. Many of them get absolutely furious and kick him out until he changes his behaviour.’

A point made repeatedly by young gay Arabs in interviews was that parental ignorance is a large part of the problem: the lack of public discussion about homosexuality results in a lack of level-headed and scientifically accurate newspaper articles, books and TV programmes that might help relatives to cope better. The stigma attached to homosexuality also makes it difficult for families to seek advice from their friends. Confronted by an unfamiliar situation, and with no idea how to deal with it themselves, the natural inclination of parents from a professional background is to seek help from another professional such as a psychiatrist. In Egypt this is a common middle-class reaction to a variety of behavioural ‘problems’. One (heterosexual) Egyptian recalled that his parents had sent him to a psychiatrist because he regularly smoked cannabis. The treatment failed, but he went on to become a successful journalist.

Psychotherapy in Egypt doesn’t come cheap.9 There’s also no evidence that it ‘cures’ anyone. Contrary to the prevailing medical opinion elsewhere in the world, the belief that homosexuality is some form of mental illness is widespread in the Middle East, and many of the psychiatrists who treat it do nothing to disabuse their clients.

In the West, sexual reorientation (‘reparative’) therapies are rejected by most mental health organisations but supported by some evangelical Christian groups. Treatment is not permitted in Britain, though it is offered by some therapists in mainland Europe. In the United States, the only treatment approved by the American Psychiatric Association is ‘affirmative therapy’, which aims to reconcile clients with their sexuality. For other forms of treatment, clients must sign a consent document acknowledging the APA’s view that sexual reorientation is impossible and that attempting it may cause psychological damage.10

In Egypt, treating gay men is a ‘not very prominent and very under-developed’ branch of psychiatry, Billy said. Treatments described by interviewees, either from personal experience or that of their friends, range from counselling to aversion therapy (electric shocks, etc). Futile as this may be in terms of reorientating the client, it is not necessarily a total waste of money: Billy cited several cases where failed therapy had helped to convince parents that their son would not change, and thus persuade them to accept his sexuality.

In contrast to their perplexed parents, gay youngsters from Egypt’s professional class are often well-informed about their sexuality long before it turns into a family crisis. Sometimes their knowledge comes from older or more experienced gay friends, but mostly it comes from searching the Internet.11 This of course requires basic computer literacy, access to the Internet and fluency in English (or possibly French), and is therefore only available to the better educated. ‘If it wasn’t for the Internet I wouldn’t have come to accept my sexuality,’ Salim said, but he was concerned that much of the information and advice provided by gay websites is addressed to a Western audience and may be unsuitable for people living in Arab societies. Many of these sites carry first-person ‘coming-out’ stories from Westerners who found the experience positive, or at least not as painful as they expected. The danger of this, Salim explained, is that it encourages Arab readers to do the same – and the results can be catastrophic, especially if they have no access to support and advice when relatives and friends respond badly. The difficulty of finding a sympathetic ear is illustrated by the case of one anguished Lebanese student who, knowing of nobody to turn to locally, sent an email to a professor in the United States who had written articles about Islam and homosexuality. Purely by chance, the professor knew someone in Lebanon who could help.

Having a lesbian daughter is less likely to cause a family crisis than having a gay son, according to Laila, an Egyptian lesbian in her twenties.12 Her mother had once broached the question of her sexuality by asking: ‘Do you like women?’ – to which Laila replied ‘Yes, of course.’ Her mother put the question again: ‘I mean, do you really like women? Don’t you want to get married and have children?’ That was the only time the subject had ever come up, Laila said, and even then her mother seemed relatively unconcerned.

Laila suggested two reasons for a more relaxed attitude towards lesbian daughters. One results from a heavily male-orientated society in which the hopes of traditional Arab families are pinned on their male offspring. Baby girls are not particularly welcomed and many parents continue having children until they produce a son. Boys therefore come under greater pressure than girls to live up to parental aspirations. The other factor is that lesbian inclinations remove some of a family’s usual worries as their daughter passes through her teens and early twenties. The main behavioural requirement placed on a young woman during this dangerous period is that she should not ‘dishonour’ the family by losing her virginity or getting pregnant before marriage. A daughter’s preference for women at least reassures the family that she won’t bring shame on them by getting into trouble with men.

Laila’s experience was not shared by Sahar,13 a lesbian from Beirut, however. ‘My mother found out when I was fairly young – around sixteen or seventeen – that I was interested in women, and she wasn’t happy about it,’ she said. Sahar was being treated for depression at the time and her university-educated mother decided to change the therapist. ‘The previous one was sympathetic. Instead, she took me to a very homophobic therapist who suggested all manner of ridiculous things – shock therapy and so on.’ Sahar thought it best to play along with her mother’s wishes – and still does. ‘I re-closeted myself and started going out with a guy,’ she said. ‘I’m twenty-six years old now and I shouldn’t have to be doing this, but it’s just a matter of convenience, really. My mum doesn’t mind me having gay male friends but she doesn’t like me being with women. I’ve heard and seen much more extreme reactions. At least I wasn’t kicked out of the house.’

None of the young people interviewed in Egypt had initiated a conversation about their sexuality with a parent. ‘People rarely come out to their family,’ Billy said. ‘They wouldn’t tell their parents directly but might tell an aunt or uncle or a person they really trust.’ Even so, it is a high-risk strategy: ‘For those that I know [who did tell], it was such a drama.’ Parents sometimes raise the issue, Billy said – either because they have noticed their son or daughter mixing with unconventional friends or because they have decided it is time for marriage. In Salim’s case, although his parents had been the first to broach the question of his sexuality, he said he had provoked them into doing so – mainly because he feared being pressurised into getting married. ‘I kept giving them hints, like laughing whenever they mentioned marriage.’

Marriage is more or less obligatory in traditional Arab households. Arranged marriages are widespread and parents often determine the timing, as well as taking on the responsibility of finding a suitable partner. Sons and daughters who are not particularly attracted to the opposite sex may contrive to postpone it for a while but the range of plausible excuses for not marrying at all is severely limited. This presents them with an unenviable choice: to declare their sexuality (with all the consequences that can entail) or to accept that marriage is inevitable and either try to suppress their homosexual feelings or pursue outlets for them alongside marriage.

Parental pressures of this kind, although extremely common, can vary in intensity from one family to another and are not universal. ‘It depends on how you manage your career,’ Billy said. ‘There is less pressure to get married if you are focused on a career. If you’re not doing much and seem to be messing about, parents will start talking about marriage.’

There are also some families where issues of sexuality are never raised, even obliquely, and even when it must be obvious to the parents that their son or daughter does not live up to conventional expectations of heterosexuality. ‘Adagio’, the only son of an Egyptian army officer, had reached the age of twenty-five without any hints from his family about the need to marry or any questions about his sexuality. They would complain if he stayed out all night without phoning them, but they never enquired too deeply about why he was staying out.14

There is surely an element of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ in this, a feeling that it will be better for the whole family if any suspicions remain unconfirmed. In the absence of confirmation the parents can still hope for a change in their son’s behaviour. It is not entirely a forlorn hope. A point made repeatedly by interviewees in Egypt was that to be gay and Arab is often extremely lonely. Adagio said several of his gay friends had gone on to marry or were planning to do so – not because of family pressures but because they feared ‘being alone’ as they grew older. Their sexual feelings were largely unchanged by marriage, however. One of them, Adagio’s first boyfriend who had since fathered a child, complained privately that sex with his wife was not as enjoyable as it had been with Adagio. Two of Adagio’s other friends had taken a different route out of the gay life: by killing themselves.

The sense of duty that Arabs in general feel towards other members of their family is extremely powerful. Gay or lesbian Arabs are no exception to this and often they are willing to put family loyalties before their own sexuality. Hassan,15 in his early twenties, comes from a prosperous and respectable Palestinian family who have lived in the United States for many years but whose values seem largely unaffected by their move to a different culture. His eldest sister is betrothed to a young man from another Arab-American family, and it was arranged in the traditional way, with a meeting between the two families who agreed that the couple were suitable and would marry when they had finished their studies. Until then, they remain apart and do not mix with the opposite sex. Hassan’s family were unsure whether to let their daughter leave home to study but they allayed their fears by getting a relative who lives near the university to check on her at frequent intervals.

In due course the family will expect Hassan, his younger brother and his two other sisters to follow a similar path into married life, and so far Hassan has done nothing to ruffle their plans. What none of them know, however, is that he is an active member of al-Fatiha, the organisation for gay and lesbian Muslims.16 Hassan has no intention of telling them, and he hopes they will never find out because it would be a disaster for the entire household. Though he has grown up gay, he was born with inescapable responsibilities to his family.

‘I’m the eldest son of an eldest son of an eldest son,’ he said. ‘That means a lot to them. When I was born, my father took my name: he became known as Abu Hassan – the father of Hassan.17

‘Of course, my family can see that I’m not macho like my younger brother. They know that I’m sensitive, that I’m effeminate and I don’t like sport. They accept all that, but I cannot tell them that I’m gay. If I did, my sisters would never be able to marry, because we would not be a respectable family any more.’

While Hassan continues with his studies he is under no pressure to marry, but he knows the time will come and is already working on a compromise solution, as he calls it. When he reaches the age of thirty he will get married – to a lesbian from a respectable Muslim family. He is not sure if they will have same-sex partners outside the marriage but he hopes they will have children and that, to outward appearances at least, they too will be a respectable family.

* * *

GHAITH, a Syrian, grew up with his sister in a single-parent family. ‘My mum and dad got divorced when we were really young,’ he said.18 ‘It was definitely not easy for my mum. She raised us by herself and everybody’s eyes were on us. She was always scared of what people would say about how she was a single mother. I feel that in a way me and my sister were like an exam for her – if we screwed up everybody was going to blame her. This was her biggest concern when she heard I was gay.’

In 1999, Ghaith was in his final year studying fashion design in Damascus, where he often hung around with five other student friends. ‘We were three boys and three girls,’ he said. ‘We were like boyfriends and girlfriends, but in Syria boyfriends and girlfriends don’t sleep together. They don’t even kiss each other or anything, except rarely. Of course, I had known that I was gay for a long time but I never allowed myself to even think about it until I went to college. Then, for the first time in my life I met people who had no problem with being homosexual. Most of them were homosexual themselves – they were fashion teachers.’

Ghaith developed a crush on one of his teachers. ‘I felt this thing for him that I never knew I could feel,’ he recalled. ‘I used to see him and almost pass out every day. One day I was at his place with a lot of guys and girls. We were having a party and I got drunk. My teacher said he had a problem with his back and I offered him a massage. We went into the bedroom. I was massaging him and suddenly I felt so happy. He was facing down on the bed so I turned his face towards my face and kissed him.

‘He was like … “What are you doing? You’re not gay.”’

‘I said: “Yes, I am.”’

‘It was the first time I had actually said that I was gay. After that I couldn’t see anybody or speak for almost a week. I just went to my room and stayed there, I stopped going to school, I stopped eating, I stopped doing everything. I was so upset at myself and I was going … “No, I’m not gay, I’m not gay, I’m not.” It was very difficult for me at that time. Everything in my life had suddenly changed, but I also felt this happiness too.’