13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

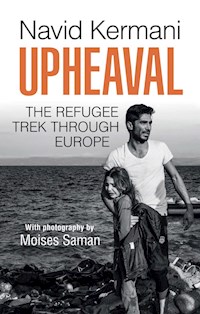

By foot, in buses, prison vans and trains, a steady stream of refugees traveled from the Greek island of Lesbos into Europe. In the autumn of 2015, award-winning writer Navid Kermani decided to accompany them on the "Balkan route." In this perceptive account from the front line of the "refugee crisis," Kermani shows how a seemingly distant world in which war and conflict rage has suddenly collided with our own. Kermani describes the situation on the Turkish west coast where thousands of refugees live in the most desperate conditions, waiting to take the perilous journey across the Mediterranean. Then, on Lesbos, he observes the culture shock amongst those who have survived the ordeal by sea. He speaks to aid workers and politicians, but most importantly of all to the refugees themselves, asking those who have come from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere what has driven them to risk everything and embark on the long and treacherous journey to Europe.

With great sensitivity Kermani reveals, often through small details, the cultural and political upheaval that has caused people to uproot their lives, and at the same time shining a light on Europe's inadequate and at times openly hostile response to the refugees. Interspersed with powerful images by the acclaimed photographer Moises Saman, Upheaval is a much-needed human account of a crisis we cannot ignore.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 77

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

A Strangely Softer Germany

A Great Migration

Do We Want Europe or Don’t We?

Why Are You All Coming Here?

The European Border Regime

Culture Shock

In the City Centre

Autobahn to Germany

Heavy Seas

Human Instinct

Zero Refugees Here

Bargaining for Their Lives

Chancellor Merkel’s Shoe

You Can Live without Freedom

Go Back?

Just in Time

Map

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

vi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

Upheaval

The Refugee Trek through Europe

Navid Kermani

With photography by Moises Saman

Translated by Tony Crawford

polity

First published in German as Einbruch der Wirklichkeit: Auf dem Flüchtlingstreck durch Europa © Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, Munich, 2016

This English edition © Polity Press, 2017

Photography © Moises Saman/Magnum PhotosMap © Peter Palm, Berlin/Germany

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press350 Main StreetMalden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1871-5

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Acknowledgements

From 24 September to 2 October 2015, Moises Saman and I travelled from Budapest to Izmir on assignment for the German news weekly Der Spiegel. A much shorter version of our report – about a third of the present text – appeared in the 11 October issue. I owe thanks to many people: Lothar Gorris, head of the magazine’s cultural section, Matthew Krug, photography editor, and Gordon Bertsch of Der Spiegel’s travel office all gave us the best support possible. Alex Stathopoulos of Pro Asyl, Ramona Lenz and Thomas Gebauer of medico international, and Hagen Knopp of Watch the Med helped us plan our route and put us in touch with people along the way. Basşak Demir helped me prepare for the visit to Turkey. Nicole Courtney-Leaver got us the necessary credentials and was very helpful in many other matters. My assistant Florian Bigge kept us supplied during the trip with current information and situation reports from Germany. The writer Vladimir Arsenijević and the cultural manager Milena Berić of Belgrade picked us up at the Hungarian–Serbian border and accompanied us as far as Thessaloniki Airport. Vladimir and Milena were much more than our drivers, interpreters and guides: they gave us the invaluable gifts of their insights, their inexhaustible contacts throughout the Balkan region, and most of all their friendship. Finally, I thank my editor at C. H. Beck, Dr Ulrich Nolte, and his assistant Gisela Muhn, who supervised the book version.

Immediately after we left Lesbos, my brother Khalil and my sister-in-law Bita arrived there and initiated an aid project for the refugees. See http://avicenna-hilfswerk.de/avicenna-english/ to find out more or to donate.

Navid KermaniCologne, 10 December 2015

A Strangely Softer Germany

It was a strangely softer Germany that I left in late September 2015. In the railway stations of the big cities, between the travellers hurrying to their trains or their exits, strangers lay on green foam mats. No one chased them away or caused a fuss about the public disorder; on the contrary, local residents in yellow safety vests knelt beside the strangers to offer them tea and sandwiches or to play with their children. Outside the stations were tents and people going into them, carrying box after box – food, clothing, toys, medicines – donations from the populace. When other countries stopped the strangers and bullied them so badly that they tried to escape on foot along the motorways, Germany sent special trains to fetch them, and, wherever they arrived, crowds of citizens and even mayors were on the platforms to applaud them. Local newspapers and national TV networks alike told their audiences what every single German could do to help, and overnight even the most xenophobic of the German papers began recounting the strangers’ life stories, telling so compellingly of war, of oppression, and of the travails and dangers of their flight that it was impossible, even in the pubs, to think rescuing them a bad idea. In the towns and villages, citizens’ committees formed – not against the new neighbours, but for them. The football clubs in the national league – the Bundesliga – sewed patches on their jerseys saying refugees were welcome, and the most popular actors and singers inveighed against all Germans who did not show solidarity.

Yes, there was also animosity against the strangers, there were attacks, but now the politicians leapt to the defence of the threatened refugees and visited their shelters. The chancellor herself, the hard-headed German chancellor who, just a few weeks before, had been helpless to comfort a weeping girl from Palestine, amazed everyone by an outburst of emotion as she defended the right to political asylum. Her whole government, for that matter: was this the same government that, a few months earlier, had been the loudest critic of Italy’s Mare Nostrum project to save boat refugees from drowning? And the state, the German administration: to provide for hundreds of thousands of new refugees within a few weeks exceeded any foreseeable contingency, and yet it was managed surprisingly well. At most there was discreet grumbling about schools being unable to use their sports halls, about furtive estimates of the costs, which might entail new debt. And what if another million refugees were to come next year, and still more the year after?

It was a strangely softer Germany I left behind, as if its greyness, usually so stiff and forbidding, was covered with powdered sugar. Just as I was leaving, I couldn’t help thinking, or perhaps I already felt, how easily powdered sugar can be blown away.

A Great Migration

From the veranda of my hotel on Lesbos, I can see the Turkish coast a few kilometres away across the Mediterranean Sea. It is half past eight in the morning, and right now, as I write this sentence, the first group of refugees is coming round the bend in the lane below – all of them Afghans, from their appearance and the snatches I can hear of their talk, and all men; their inflatable boat has apparently landed in Europe without major difficulties. They do not look drenched or frozen, as many other refugees do who land, for fear of the police, below cliffs or steep, overgrown slopes, or who make the crossing in boats that are desperately overcrowded. Now that they have survived the most dangerous part of their long journey, they are cheerful, positively chipper; they’re talking and joking, looking like a group of young daytrippers, carrying nothing but hand luggage at most. They don’t know yet, though, that they have a steeply climbing march of several kilometres ahead of them to get to one of the buses that the United Nations refugee agency has chartered to take new arrivals to the port of Mytilene; nor have they any inkling that, because the United Nations doesn’t have enough buses, most of the refugees have to walk the fifty-five kilometres to the port, with no food, no sleeping bags, no warm clothes – and the sun is still glaring during the day, while the nights have grown chilly.