Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

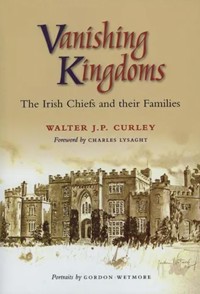

Vanishing Kingdoms combines an account of aristocracy and its history in Ireland with an interview-based description of twenty recognized Irish chiefs of the name and their family backgrounds. Three of them, The O'Brien, O'Conor Don and The O'Neill, have legitimate claims to high kingship; all are descendants of territorial kings and sub-kings. For the most part shorn of their privileges and territories in a democratized, socially fluid Ireland of the twenty-first century, as a group the chiefs exercise a continuing fascination and a living link to the past, leaving an imaginative yet tangible mark on the Irish landscape. The families are grouped by province. Through the unfolding diorama of these individual family stories, Vanishing Kingdoms gives an enriching view of Irish history and society. Contemporary portraits of the current chiefs, photographs and engravings of their dwellings, past and present, complement a vivid narrative.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 260

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2004

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Vanishing Kingdoms

TheIrishChiefsandtheirFamilies

WALTER J.P. CURLEY

Foreword byCHARLES LYSAGHT

Portraits byGORDON WETMORE

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

For John and James

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Map

Foreword by Charles Lysaght

Introduction

I The Old Order

II The Claimants

III The Chiefs

IV The Past and the Future

V The Royal Survivors

ULSTER

The O’Neill *

The O’Dogherty

The O’Donnell

MacDonnell

The Maguire

MUNSTER

The O’Brien*

The O’Callaghan

The O’Carroll

The O’Donovan

The O’Donoghue

The McGillycuddy

The O’Grady

The O’Long

LEINSTER

The Fox

The O’Morchoe

The MacMorrough Kavanagh

CONNACHT

O’Conor Don*

The MacDermot

The O’Kelly

The O’Rorke

Postscript 179

Bibliography and Further Reading 182

Index 187

Copyright

* Claimants to the high kingship

Illustrations

PORTRAITS

by Gordon Wetmore

Hugo O’Neill42

Dr Don Ramon O’Dogherty50

Randal MacDonnell64

Terence Maguire72

Conor Myles John O’Brien80

Don Juan O’Callaghan88

Frederick James O’Carroll94

Daniel O’Donovan and his wife, Frances Jane O’Donovan102

Geoffrey Vincent Paul O’Donoghue108

Richard Denys Wyer McGillycuddy114

Henry O’Grady120

Denis Clement Long and his wife, Lester Long126

Douglas John Fox132

David O’Morchoe138

William Butler MacMorrough Kavanagh144

Andrew MacMorrough Kavanagh144

Desmond Roderic O’Conor154

Rory MacDermot160

Walter Lionel O’Kelly166

Geoffrey Philip O’Rorke172

ENGRAVINGS AND PHOTOGRAPHS

Shane’s Castle, Co. Antrim48

Burt Castle, Inishowen, Co. Donegal56

Donegal Castle63

Glenarm Castle, Co. Antrim,70

Enniskillen Castle, Co. Fermanagh

‘Penal’ Chalice

Great Medieval Chalice (engraving)

Great Medieval Chalice77

Dromoland Castle, Co. Clare87

Dromaneen Castle, Co. Cork92

O’Carroll’s Castle, Emmell West, Co. Offaly100

Hollybrook House, Skibbereen, Co. Cork106–7

Ross Castle, Killarney, Co. Kerry113

The Reeks, Beaufort, Co. Kerry119

Kilballyowen House, Bruff, Co. Limerick125

Mount Long Castle, Co. Cork129

Galtrim House, Dunsany, Co. Meath136

Looking West from Oulart Hill, Co. Wexford143

Borris House, Co. Carlow151

Clonalis House, Co. Roscommon159

Coolavin House, Co. Sligo165

Gallagh Castle, Co. Galway170

Dromahair Castle, Co. Leitrim177

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the descendants of the Irish kings, chiefs of the name, and to their families, who received me and the artist Gordon Wetmore with a high level of co-operation – and hospitality. Also, from the outset of the project, Verette and William Finlay, former chairman of the National Gallery and governor of the Bank of Ireland, gave me guidance and counsel; and later, Desmond FitzGerald, Knight of Glin, provided an additional critical eye and bracing candour to the developing manuscript.

John Campbell and Richard Ryan, former Irish ambassadors to France, Spain, Portugal, and the United Nations, made substantive contributions to my research. And I am delighted that author, historian and friend Charles Lysaght provided such keen insight and reflections in his Foreword.

My cherished long-time associate, Eleanor Bennett of New York, who can spot a split infinitive from twenty paces, transcribed the text with rare prowess and patience. I was also fortunate to have the support of Billy Murphy of Limerick – photo-historian, philosopher, and expert driver – who transported us around Ireland during our visits to the hereditary chiefs.

The initial catalyst for this book was my old colleague, J. Mabon Childs of Pennsylvania, whose portrait had been painted by Gordon Wetmore.

I am indebted to the many helpful people in Ireland who were intrigued by (and often related to) the ancient dynastic families. Fortunately, my own immediate family in America – daughter Peggy Curley Wiles, a teacher; daughter-in-law Jane Bayard Curley, an art historian; and son Patrick, an architect – also lent their professional skills and judgment to the project.

As this book developed, Antony Farrell, editor-in-chief of The Lilliput Press, gave me the crucial benefit of his erudition along with his friendship.

In the final analysis, VanishingKingdoms:TheIrishChiefsandtheirFamilies would not exist without the historian’s eye, good humour, and enduring encouragement provided by my dear wife, Mary Walton Curley.

Map

Foreword

As a people we Irish are often oblivious to what is most interesting and valuable about ourselves until some well-disposed visitor draws it to our attention. There can be few visitors as well disposed to Ireland as Walter Curley, whom I first met at Clonalis, the seat of the O’Conor Don in 1976 on the very day that his friend the British Ambassador Christopher Ewart-Biggs was assassinated in Dublin. Walter Curley was then United States Ambassador to Ireland and had long been the proud owner of a house in Mayo. He later became Ambassador in Paris. He retained his Irish connection as a director of the Bank of Ireland and as a frequent visitor, always glad to assist Irish people or their projects. It is interesting that the Ambassador should be drawn to the living descendants of the Gaelic chieftains as a noteworthy feature of our national life. It is also opportune at a time when our government, through the Genealogical Office, has decided to terminate the official recognition of them, initiated in 1944, that reached its apotheosis when President Mary Robinson received the Standing Council of Chiefs and Chieftains after their inaugural meeting in 1991.

Apart from the general human interest in ancestry and in the vicissitudes of families, the chieftains link modern Ireland with the ancient Gaelic order that preceded the English conquest and remind us that we are an ancient nation that had our own culture and, what was then synonymous, our own aristocracy. The long struggle to reassert an Irish national identity can only be understood against this background; it was the struggle of those who were dispossessed not just oppressed.

So it was that the founding fathers of the independent state placed emphasis on preserving what was left of the old Gaelic Ireland, whether it took the form of ancient monuments or the Irish language. They even flirted with the revival of the Brehon Law but this proved impracticable. The courtesy recognition given to the descendants of the Gaelic chieftains after 1944 by the Genealogical Office that took over the Office of Arms was of a piece with this. It is interesting that Mr de Valera, who had come to the national movement through the Gaelic League, gave his personal approval to the project when it was put to him by the first Chief Herald, a fellow Gaelgeoir Edward MacLysaght. A decade later, as Chancellor of the National University, de Valera was pleased to confer an honorary degree on the lineal descendant of the ancient O’Donnells who was the Duke of Tetuan in the nobility of Spain.

The chieftains surveyed by Ambassador Curley in this engaging volume may be seen as a microcosm of the fate of the upper class of the old Gaelic order. There were those who accepted the opening to integrate themselves into the new English Protestant Ascendancy established as part of the conquest of Ireland in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There were those who departed Ireland rather than accept this new order and became part of the aristocracies of the Catholic powers of continental Europe. There were those who hung on as minor Catholic gentry and they are rightly celebrated. They produced from their number several leading nineteenth-century figures, notably our first great political leader, the Liberator Daniel O’Connell, who thus personified the link between the old Gaelic order and the modern Irish democracy. But it is clear that a vast number of chieftain families either died out or, more probably, descended into such obscurity and illiteracy that their lineage cannot easily be traced from documentary sources.

That there must have been a large class of dispossessed Irish Catholic gentry is evidenced by an early eighteenth-century Act that criminalized ‘all loose idle vagrants and such as pretend to be Irish gentlemen and will not work’. The best authenticated example of social descent of this kind is the case of The McSweeney Doe, whose early nineteenth-century ancestor, a travelling tinsmith, was identified to the antiquarian John O’Donovan and whose dynastic claim was under consideration by the Chief Herald in 2003 when the decision was taken to terminate courtesy recognition. The uncertainty engendered by the likely social descent of many of those of chieftain stock was, of course, a ripe breeding ground for bogus claims of all sorts. Equally, it was probably the case that the presence among the downtrodden Irish peasantry of the descendants of the old chieftain caste must have contributed to the sense of dispossession that was to fuel the Irish nationalist movement and to distinguish it from normal social egalitarian movements.

Edward MacLysaght inherited a situation where a list of chieftains had long been published annually in Thom’sDirectory and Whitaker’sAlmanac, which stated that they were not officially recognized but had become recognized by courtesy. They were The Fox, The MacCarthy Reagh, The MacDermot, The MacDermot-Roe, The McGillycuddy of the Reeks, The O’Callaghan, O’Conor Don, The O’Donoghue of the Glens, The O’Doneven of Clerahan, The O’Donovan, The O’Grady, The O’Mahony of Kerry, The O’Kelly of Hy-Maine, The O’Morchoe, The O’Neill, The O’Rourke, The O’Shee, and The O’Toole. It is noteworthy that others who used the designation ‘The’ at that time, such as O’Phelan, Chief of the Decies, The MacEgan, The O’Brenan or The O’Rahilly, were not included.

MacLysaght considered that it was important to authenticate genealogically the claims of all those using the designation ‘The’ in order to expose those who were bogus. With the assistance of a keen genealogist called Terence Gray all claimants were examined to ascertain if they could prove descent on the eldest male line from the last chiefs of the name. Of those listed in Thom’s, a number did not pass muster; they were The MacCarthy Reagh, The O’Callaghan (Colonel O’Callaghan-Westropp), The O’Doneven of Clerahan, The O’Mahony of Kerry, The O’Rourke and The O’Shee. The MacDermot Roe was found to have been dormant since 1917. A notice was placed in the official government gazette, IrisOifigiúil, in December 1944 listing ten chiefs of the name. In the case of two others, The O’Grady of Kilballyowen and The O’Kelly of Gallagh and Tycooly, it was stated that, while not chieftainries in the strict sense, they had a legal right to their title having been long styled under these designations, and that their pedigrees, duly authenticated, were on record in the Genealogical Office. In the following year The O’Morchoe was listed together with two others who had not been included in Thom’s, namely, The O’Brien of Thomond, who was Lord Inchiquin and The O’Donel of Tir Connell, a Dublin civil servant who had not sought recognition before being informed of his entitlement by the Chief Herald. Other chiefs of the name were recognized under succeeding chief heralds while The O’Toole became dormant on the death of the French count of the name, leaving us with the twenty included in this book.

It was an objection to MacLysaght’s action that succession to Gaelic chieftainries under Brehon Law was governed not by primogeniture but by a system of tanistry, under which an heir apparent (called tánaise) was chosen by the immediate family group of the existing chieftain extending to second cousins, known as the derbhfine.*

MacLysaght’s justification was that the system of primogeniture had become the general rule before the end of the Gaelic Order and that what he was doing had the merit of distinguishing those with reasonable ancestral claims from those who were bogus. The courtesy recognition given was, he pointed out, clearly stated to be no more than a statement of genealogical fact. At a practical level it would not have been possible to revive the Brehon law of succession retrospectively. To begin again to apply it with future effect, as was suggested in 1998 by the Standing Council of Chiefs and Chieftains, would have little logic.

Ironically, the objective of avoiding bogus claims that had been MacLysaght’s motivation, was frustrated when in 1989 MacLysaght’s second next successor as Chief Herald, Donal Begley, recognized Terence MacCarthy as The MacCarthy Mór on the basis of a pedigree registered as authentic by his predecessor Gerard Slevin. The recognition was withdrawn in 1999 when it was established that the pedigree had been registered in reliance on a forged letter. This, as Ambassador Curley indicates at various points, has cast a shadow over at least some of those who were recognized about the same time, and enquiries were initiated by the Chief Herald.

Finally in 2003 the Chief Herald Brendan O’Donoghue decided that the practice of granting courtesy recognition as chief of the name should be discontinued, and that no further action should be taken in relation to the applications on hand for courtesy recognition, or in relation to the review of certain cases in which recognition was granted in the years 1989–95.

This decision was stated to be based on advice received from the Office of the Attorney General that:

There is not, and never was, any statutory or legal basis for the practice of granting courtesy recognition as chief of the name;

In the absence of an appropriate basis in law, the practice of granting courtesy recognition should not be continued by the Genealogical Office; and

Even if a sound legal basis for the system existed, it would not be permissible for me to review and reverse decisions made by a previous Chief Herald except in particular situations, for example, where decisions were based on statements or documents which were clearly false or misleading in material respects.

The decision of the Chief Herald to withdraw from the business of designating chieftains for courtesy recognition is understandable in the light of what had occurred. But it must be questioned if it is responsible for the Chief Herald to relinquish his responsibilities leaving questions over the official authentication given to those recognized in recent decades. It is a pity that the full legal option of the Office of the Attorney General was not published as the account given implies that because there was no specific statutory basis for granting courtesy recognition as chief of the name it had no basis in law. This is a nonsequitur. In law, a function of a government department does not have to have a specific statutory basis to be legal. There are many activities of government departments that have no statutory basis other than the annual Appropriation Act and the fact that they are within the general functions of the departments concerned. The authentication of pedigrees was among the functions of the Office of Arms taken over by the Genealogical Office in 1943 and, as such, must be regarded as being a legitimate activity unless precluded by statute. Insofar as the courtesy recognition of a chief of the name was no more than an authentication of a pedigree, it had a clear legal basis.

At this juncture it is, I think, essential to disentangle the issue of courtesy recognition from that of the authentication of pedigrees and to decide what should be done about each. It is difficult to give a precise meaning to the concept of courtesy recognition but it probably means nothing more than that in courtesy one addresses a person by the name by which they are generally known. The law sets no limits to the names by which a person may be known. While the Constitution states that titles of nobility shall not be conferred by the State and that no titles of nobility or honour may be accepted by any citizen except with the prior approval of the government, it has never been the law that citizens or other people may not use titles in this State; indeed, this has been done even in official contexts. All this may create difficulties for governments because use of a name may be prayed in aid as a form of recognition, especially if used on passports or other official documents. The whole issue, like the thorny issue of precedence, needs to be addressed authoritatively. But, meanwhile, if recognition is accorded to titles conferred by English or British kings and queens of Ireland and to those conferred by foreign sovereigns, including the Pope, it may be questioned if it is right to withhold the courtesy of recognition to names used by those certified by the Chief Herald to be descended from a Gaelic chieftain.

The authentication of pedigrees was achieved under the system of registered pedigrees verified and authenticated by the Ulster King-of-Arms and, after 1943, by the Chief Herald. This facility was withdrawn in recent years and the Genealogical Office now examines pedigrees only in the context of confirming if a person is entitled to arms previously granted. That the Chief Herald should no longer register pedigrees as authentic in the Genealogical Office seems to belie the central function incorporated in the title of the office. It is surely in the public interest that there should be some official body that authenticates pedigrees. As part of a general function of authenticating pedigrees it would be proper to validate the line of those claiming to be descended from Gaelic chieftains. This is, incidentally, no more than the Ulster King-of-Arms was prepared to do in the eighteenth century for the descendants of the Gaelic nobility – the Wild Geese – who emigrated to continental Europe. If their pedigrees are authenticated, those choosing to name themselves in the style of a Gaelic chieftain would then be able to refer to this in their entries in books of reference. This was the position before 1943. It may be suggested that the Chief Herald should authenticate descent in the female line from Gaelic chieftains – one thinks of the descent of the Esmondes from the O’Flaherty chieftains of Iar-Chonnacht and of the More O’Ferralls from the O’More chieftains of Leix. In this age of transparency it would also be appropriate that authenticated pedigrees should be a matter of public record so that scholars and other interested parties have access to the material upon which they are based.

In the absence of any authentication of Gaelic pedigrees by the Chief Herald in the Genealogical Office, the Council of Chiefs and Chieftains may arrogate the function to themselves. This would not be altogether satisfactory in view of the queries that have been raised about the pedigrees of some of its members. Otherwise, those seeking to authenticate such pedigrees and, indeed, other Irish pedigrees, may have to resort to the Ulster King-of-Arms in London. This would be humiliating for the Genealogical Office and defeat the very purpose for which it was established.

To have compounded the withdrawal of courtesy recognition with a discontinuance of the authentication of pedigrees going back before the English conquest breaks a link between the modern Irish State and the old Gaelic nation, and is a strange action in a country that, as Ambassador Curley rightly points out, boasts some of the oldest authenticated pedigrees in Europe. The action taken may be seen as symbolic of the fact that the modern inclusive Ireland no longer seeks justification for its existence in an identification with the old Gaelic nation. It may be healthy that we do not attempt to identify modern Ireland only with the Gaelic tradition. But neither should we go to the opposite extreme of neglecting or rejecting that tradition. In the long run no nation is enriched in the eyes of the world if it turns its back on its roots. This delightful book directs our attention to the antiquity of our roots for which we should be grateful.

CHARLES LYSAGHT

Dublin,September2004

*The point has been made that the action was contrary to the legislation that had abolished Gaelic chieftains, which had been carried over into the law of the independent Irish State in 1922 with the rest of the law then in force. However, it could be countered that the legislation abolishing the Gaelic chieftainaries was of a racial character that would have precluded its being carried over into the domestic law of the independent Irish State that traced its legitimacy on the Proclamation of an Irish Republic in Easter 1916, which claimed a continuity between the Irish Republic and the old Gaelic nation.

Introduction

Royalty and hereditary nobility hold a certain fascination for many ordinary citizens (or subjects, as the case may be). Emotions on the matter range from admiration, deep dedication, and often sycophancy, to curiosity, envy and aversion. At all social and intellectual levels, in virtually every culture, a part of our human intellect seems to be beguiled by the hereditarily select. Ireland is no exception.

Much of the seductive aura clinging to these figures and families stems from the power that usually accompanies sovereignty and historic entitlement. In varying degrees many people are intrigued by the intricate skeins of bloodlines and politics; even when the power has been long removed, the mystique often continues in an enduring after-glow.

In 2004 Europe has ten hereditary sovereign states – kingdoms and principalities: Belgium, Denmark, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Monaco, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Only ninety years ago at the outbreak of World War I there were thirty-five reigning European monarchs, and only four European republics – France, Portugal, Switzerland and San Marino. Today, only twenty-nine hereditary sovereignties in the world are still ‘in business’: in addition to the ten Europeans, the total includes, in Africa, Lesotho, Morocco and Swaziland; in the Middle East, Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates; and in Asia, Bhutan, Brunei, Cambodia, Japan, Malaysia, Nepal, Thailand, Tonga and Western Samoa.

A century ago British social scientist Walter Bagehot wrote: ‘Above all, royalty is to be reverenced. In its mystery is its life; we must not let day light in upon the magic.’ Many times in history, however, the ‘day light’ has arrived with sudden devastation and sweeping changes. Although monarchies that have been toppled are ostensibly relegated to the dustbins of history – in the case of Ireland, centuries ago – the memories, the auras, and the magnetism seem to linger on. They survive most persistently in continental Europe where some former monarchs (as well as valid Claimants to the empty thrones) await patiently a call to return; these figures are not only dejure the keepers of the royal flame, but are often the focal points of active political movements bent on returning the lapsed nations to the monarchical system. A shiver of hope charged through diverse royal veins-in-exile in 1983 when the son of Don Juan, Count of Barcelona – the Bourbon Pretender – was returned as His Majesty King Juan Carlos I to the throne of Spain, which had been empty since his grandfather, King Alfonso XIII, was ousted in 1931. Another glimmer of optimism encouraged the royal exiles when former King Simeon of Bulgaria, who lost his throne in 1946, became Prime Minister of his homeland in 2001.

Royalty-watchers everywhere keenly follow the pomp, circumstance and minutiae of the currently ruling families and of the nobles surrounding them in the system. These happenings are regularly in the media – and some have relevance. It is impossible to calculate accurately the positive financial impact, for example, that the British monarchy has on tourism, or the negative effects that its dissolution would have on the entire economy of the United Kingdom; all political parties in Great Britain readily concede that the mere existence of the monarchy has enormous economic influence on their country’s well-being. While this benefit is not,perse, an overwhelming justification for that particular form of government, it is certainly not a trivial factor in it.

The choice between a dynastic monarchical system and a republican or other governing process has been discussed for centuries. Historians, politicians and ordinary people in many parts of the world, by their very natures, will assure that this debate persists on into the future. (Even in the American presidential primary campaigns in the Spring of 2000, semantic echoes of the old argument about dynasties were heard in the rhetoric of the opponents of George W. Bush, the governor of Texas, during his battle to become the Republican Party’s nominee for the White House: opponents repeatedly called for ‘an election not a coronation’.) Whether the monarchs are incumbent or merely hopeful, the enchantment of the royals and their descendants for many people remains undiminished.

Americans are most familiar with the names and styles of European royalty and nobility – especially those in Britain; for generations English lords and ladies, along with the royal dukes and princes, have been striding, sashaying, fox-trotting and galloping through countless novels, plays, films and, indeed, through the personal lives of many Americans. That aristocratic segment of British society is still well entrenched: titles abound and new ones continue to be granted by Queen Elizabeth II, a sovereign whose own special status endures with unfailing fascination for knights and commoners alike. The Anglo-Saxon monarchy, although buffeted in recent years both by scandal and pedestrian behaviour within the royal family itself and by outbursts of native English republicanism, continues its march through history to the delight of royalty buffs throughout the world. Similarly, with the other nine countries in Europe where sovereigns still reign, a substantial segment of the global public follows in the media the royal activities with unabashed curiosity.

Not counting the former kingdoms of Bavaria, Hanover, Serbia, Saxony, Württemberg and the Two Sicilies, the duchies of Parma, Oldenberg and Mecklenburg and the principalities of Anhalt, Baden, Hesse, Lippe-Biesterfeld, Schramburg-Lippe and Montenegro, which were variously incorporated into the imperial realms of Germany and Austro-Hungary and into the kingdoms of Italy and Yugoslavia after World War I, there are, in 2004, fourteen sovereign, previously monarchist countries in continental Europe: Albania, Austria, Bulgaria, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, Russia, Turkey and Yugoslavia that were shorn of their hereditary ruling dynasties relatively recently. In many of these nations, noble titles continue in daily use, socially if not officially. In France, for instance, there are hundreds of noble families, descended from various royal regimes, who are part of the warp and woof of the broader social fabric. In the French Republic, these patricians thread their way through modern society in every province, in every sort of enterprise and profession. In Italy, Germany, Austria – actually in all the former monarchies except those previously gripped tightly within the Soviet bloc – bankers, doctors, farmers, diplomats, corporate executives and others with titles of nobility carry on without a royal house in place, but with their own pedigrees happily displayed and socially acknowledged.

Russian, Polish, Hungarian and other Eastern European royal refugees from the Soviet system, have surfaced in their native lands to try to reclaim their hereditary positions or at least to capitalize somehow on their heritage For the most part they are welcomed into the newly democratic societies.

From an historical standpoint Ireland can, of course, be listed among the countries in Europe that were ruled by hereditary monarchies. There is a surprising number of the old ruling Gaelic dynasties whose unbroken lines reach back more than forty generations.

During my almost fifty years of association with Ireland – as a diplomat and as a private resident in County Mayo – I have encountered more than mere traces of the old Celtic royals. Similarly, my colleague Gordon Wetmore, living and painting in County Carlow, has met a number of dynastic families whose ancestors were hereditary rulers. In 2000 we decided to seek out the authenticated descendants of the Irish rulers and to chronicle their links to Ireland’s past. The search lasted three years and spread to the United Kingdom, Europe, Africa, Australia, the United States and of course, Ireland.

The family sagas of these dynasts, the current chiefs of the name – stretching over a period of eleven centuries – constitute a history of Ireland itself. These are the stories of the Irish kings from AD 900 to 2004.

I

The Old Order

A new horizon for royalty-watching has recently been emerging from the mists of history. In 1944, after decades of research, academic debate and historical soul-searching, Ireland began the official recognition of the hereditary titles of the great Gaelic families. The about-to-be Republic’s decision followed intense documentation that had publicly identified the survivors of the royal Gaelic dynasties that, historians agree, are amongst the oldest in Europe.

In 1991 the Standing Council of Irish Chiefs was officially instituted; the President of Ireland, Mary Robinson, bestowing an important protocolary embrace, invited the Council to have its inaugural reception at Áras an Uachtarán, the presidential residence in the Phoenix Park, Dublin. There are only twenty of these noble Irish dynastic families who have survived the turbulent centuries, who maintain their ancient titles and who were now formally acknowledged by the government.

The invasions, occupations, confiscations, rebellions, famines and wars that have swept across the island over the centuries had virtually obliterated the ancient royal dynasties – at least the purely Gaelic-Celtic trappings of them. The Irish, from time immemorial, however, have been ardent genealogists dedicated to preserving the identities and relationships of their families in the face of great opposition, particularly during the invasions by the English and the Normans.

With ever-changing degrees of success, for almost eight hundred years, the English strove to eliminate the dangerous threat of attack by disparate but fierce Gaelic chiefs, whose Celtic culture – including language and religion – alien to Anglo-Saxon-Norman England; it was a periodic but relentlessly violent and mutually bruising process driven by the English urge to expand and colonize. The English Crown was further prodded by its chronic dread of an invasion of Britain by French and/or Spanish (or, in modern times, even German) forces, in alliance with the Irish, possibly striking from several directions. That fear was justified several times in history. But Ireland eventually survived into the modern era as an independent nation.

The island is now politically four-fifths whole: the six counties in Northern Ireland are still partitioned as a part of the United Kingdom; the ancient animosities – referred to by British Foreign Office functionaries as ‘the Irish Question’, ‘the Ulster Problem’ or ‘the Troubles’ – are still alive there, but with a hope of diminished violence and increased co-operation between the historical antagonists. The other twenty-six counties comprise the Republic of Ireland, which was officially created on Easter Monday 1949. In the early 1990s and until 2003, Ireland (or Éire, as the twenty-six counties are sometimes referred to) became one of the most dynamic economies in Europe, producing an unprecedented prosperity referred to admiringly in the world press as the ‘Celtic Tiger’.

To subdue a nation, the first essential had been to destroy or render impotent its leadership: the kings, the chiefs, the aristocracy, the spiritual and intellectual powers. Although ultimately abandoned, this strategy– in varying forms and under different reigns – was carried out effectively by the English in Ireland over the centuries: the aristocratic native Irish families were mostly