Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Drawing from first-hand interviews, diaries and memoirs of those involved in the VE Day celebrations in 1945, VE Day: The People's Story paints an enthralling picture of a day that marked the end of the war in Europe and the beginning of a new era. VE Day affected millions of people in countless ways, and the voices in this book - from both Britain and abroad, from civilians and service men and women, from the famous and the not-so-famous - provide a valuable social picture of the times. Mixed with humour as well as tragedy, rejoicing as well as sadness, regrets of the past and hopes for the future, VE Day: The People's Story is an inspiring record of one of the great turning points in history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Author

Russell Miller is the author of Nothing Less Than Victory, The Oral History of D-Day; Magnum, Fifty Years at the Front Line of History; Behind the Lines, The Oral History of Special Operations in World War Two; and Codename Tricycle, The True Story of the Second World War’s Most Extraordinary Double Agent.

‘Let war yield to peace, laurels to paeans’

Cicero (106-43 BC)

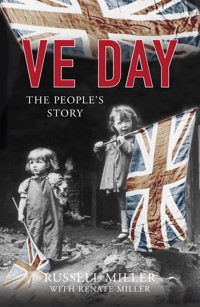

Cover illustrations: Front: courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (Image no. HU49414); Back: courtesy of Steve Nicholas.

First published 1995 by Michael Joseph Ltd

This paperback edition published 2020

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Russell Miller, 1995, 2007, 2020

The right of Russell Miller to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9571 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Illustrations

Permissions

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Tuesday 1 May: The Death of Hitler

2 Wednesday 2 May: Before the Euphoria, the Horror

3 Thursday 3 May: Collapse of the Reich

4 Friday 4 May: Ceasefire in the West

5 Saturday 5 May: Is It the End?

6 Saturday 5 May: Defeat

7 Sunday 6 May & Early Hours Monday 7 May: Unconditional Surrender

8 Monday 7 May: Why Are We Waiting?

9 Tuesday 8 May Morning: Victory, At Last

10 Tuesday 8 May Afternoon: Good Old Winnie!

11 Tuesday 8 May Evening: Bonfire Night

12 Tuesday 8 May: Just Another Day

13 Wednesday 9 May: Mopping Up the Victory

14 Thursday 10 May: After the Euphoria, the Reality

Notes

Bibliography

Illustrations

1. Soviet soldiers hoist the flag over the Reichstag (Topham Picturepoint)

2. Picture purportedly of Hitler after his death (Popperfoto)

3. US and Russian troops link up at the River Elbe (Hulton Deutsch Collection)

4. General Dwight D. Eisenhower and fellow officers at Ohrdruf concentration camp (Hulton Deutsch Collection)

5. British Honey tanks patrol the streets of Hamburg (Hulton Deutsch Collection)

6. Delegates from the German armed forces visit 21st Army Group Headquarters (Topham Picturepoint)

7. Field Marshal Montgomery reads the surrender terms to German officers (Topham Picturepoint)

8. General Dwight D. Eisenhower makes his victory speech at Rheims (Topham Picturepoint)

9. Eisenhower holds the pens, in the form of a victory ‘V’, used to sign the unconditional surrender (Topham Picturepoint)

10. The Daily Mail announcement on 8 May 1945 (Topham Picturepoint)

11. A crowd of twenty thousand people cheer the Royal Family (Hulton Deutsch Collection)

12. The Royal Family with Winston Churchill (Hulton Deutsch Collection)

13. A wounded American serviceman watches ticker tape rain down in New York (Hulton Deutsch Collection)

14. Servicemen and civilians celebrating in Manchester (Topham Picturepoint)

15. A Parisian crowd celebrates VE Day at the Place de l’Opera (Tophâm Picturepoint)

16. St Paul’s Cathedral, floodlit (Hulton Deutsch Collection)

17. Alan Ritchie’s sketch, Hemslo, north-west Germany (Alan Ritchie)

18. The author at a street party (Russell Miller)

19. Winifred Watson and her husband on their wedding day (Winifred Watson)

20. Private John Frost (John Frost)

21. David Langdon’s cartoon of the VE Day mood (David Langdon)

22. Evening News vans waiting to deliver newspapers on 8 May (Popperfoto)

23. Local women dancing for joy in Charlton-on-Medlock, Lancashire (Topham Picturepoint)

24. A car-load of merrymakers throws caution to the wind (Popperfoto)

25. The happy and not-so-happy (Hulton-Deutsch)

(Copyright holders are indicated in italics)

Permissions

The author and publishers would like to thank the following for permission to reproduce copyright material: British Broadcasting Corporation for extracts from the BBC Radio Collection tapes, Victory in Europe; the Trustees of the Mass Observation Archive, University of Sussex for Mass Observation Archive material reproduced by permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London; Imperial War Museum for material from their Sound Archives; Falling Wall Press for Nella’s Last War: A Mother’s Last Diary by Richard Broad and Susie Fleming; Heinemann Ltd for Three Years with Eisenhower: The Personal Diary of Captain Harry C. Butcher; Little Brown Ltd for Will the Real Ian Carmichael … by Ian Carmichael; S. Fischer Verlag GmbH for Zwischenbilanz by Guenter de Bruyn; Hodder Headline Ltd for Richard Dimbleby by Jonathan Dimbleby; HMSO (Crown copyright is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO) for History of the Second World War, Civil Affairs and Military Government in North West Europe 1944–46 by F.S.V. Donnison; Gollancz Ltd for Paris Journal 1944–65 by Janet Flanner; Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. for The War 1939–45 by Desmond Flower and James Reeves; Virona Publishing for Helga by Helga Gerhardi; André Deutsch Ltd for The Sheltered Days: Growing Up in the War by Derek Lambert; Hutchinson for When We Won the War and How We Lived Then by Norman Longmate; Chatto and Windus Ltd for The Home Front by Norman Longmate; Granada Ltd for I Play as I Please by Humphrey Lyttelton; HarperCollins Ltd for The Memoirs of Field Marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein KG; the Estate of Alan Moorehead for Eclipse by Alan Moorehead; Hamish Hamilton Ltd for The Moon’s a Balloon by David Niven; Stephen Schimanski and Henry Treece (eds) for Leaves in the Storm: A Book of Diaries; and Heinemann Ltd for Wartime Women edited by Dorothy Sheridan.

(For specific reference to the above material please refer to the Notes and Bibliography. Every effort has been made to trace or contact copyright holders. The publishers will be glad to rectify, in future editions, any amendments or omissions brought to their notice.)

Acknowledgements

One of the problems about writing an oral history of VE Day is that 50 years have passed and memories are fading. It was not a difficulty with our oral history of D Day because many of the veterans who took part in such a dramatic moment of history had an extraordinarily clear and detailed recall of everything that happened to them on that day. Being in Normandy on 6 June 1944 was something you did not forget.

VE Day is different, as we rapidly discovered. Denis Norden, for example, could remember nothing except being ‘maudlin in a tent on Lüneberg Heath’. Lord Hailsham, perhaps understandably, could only recall that his son, Douglas, was christened in the crypt at the House of Commons on that day. Sir John Mills said he was too young to remember anything and Donald Sinden explained he was so busy entertaining the troops he didn’t even know it was VE Day! Sir Robin Day’s one memory is of being on a troopship and being allowed a single beer, ‘a rare treat’, to celebrate. Raymond Baxter, who was a Spitfire pilot, recalls giving joy rides to WAAFs in a little Auster; Sir Hugh Casson only remembers leaving a Ministry of Planning conference in Edinburgh and finding all the street lamps on for the first time in years. David Kossof vaguely recalls a ‘prolonged knees-up’ in Lincoln’s Inn Fields; Lord Carrington, with his battalion somewhere near Freiburg, claimed VE Day was completely unexceptional, just another working day.

It is the fallibility of memory that makes the Mass Observation archive at the University of Sussex such an invaluable resource for any author embarked on a project such as this. Mass Observation was set up in 1937, by the poet and journalist Charles Madge and the anthropologist Tom Harrisson, to ‘record the voice of the people’. At the time of VE Day its volunteer observers were out and about recording extraordinarily detailed contemporary accounts of what was happening, what people were saying and thinking. Unfortunately, a condition of being able to make use of the archive is that all contributors remain anonymous, but the authentic colour they provide is irresistible.

The staff at our local library in High Wycombe considered it a personal challenge to seek out every one of the multitude of books we requested and proved, once again, that our library service is second to none and needs to be protected against philistine governments looking for budget cuts.

We would also like to thank the courteous and helpful staff of the Sound Archives and the Department of Documents at the Imperial War Museum; the London Library, particularly Joy Eldridge of Mass Observation; Martin Tapsell and staff of the Inter-Library Lending Department of Bucks County Library; members of the National Federation of Women’s Institutes, the Royal British Legion, the War Widows’ Association and the Burma Star Association. A special word of thanks, too, to John Frost, who manages to keep track of his historic collection of newspapers in a small suburban house in north London and who also wrote a fascinating letter to his mother from Germany on VE Day.

Finally, we must express our gratitude to all those who offered up their diaries, letters and memories and for everyone who agreed to be interviewed. Not everyone could be included in this book, but all the material will be lodged in a suitable archive for the benefit of those people who will undoubtedly be writing about the centenary of VE Day in the year 2045.

Russell and Renate Miller,Buckinghamshire, 1994.

Introduction

It is a cherished legend in my family, at least cherished by me, that on the night of VE Day my mother was brought home from the pub in a wheelbarrow. I was only six at the time (well, six and three-quarters), so took no part in the celebrations, but I was thrilled beyond belief when, the following morning, I heard what had occurred. Nothing so risqué, so, so … scandalous, had ever happened in the family to my knowledge and I kept pressing various aunts and uncles for more information. Did my mother willingly get into the wheelbarrow? Why? Where did it come from? Who pushed it? Did anyone see?

The ending of the war in Europe meant little to a six-year-old; but his mother coming home from the pub in a wheelbarrow made a deep impression. I suppose in the end I realized that my Mum had been ‘tipsy’ (the rather charming euphemism then in use for being completely plastered) and that probably everyone else had been tipsy, too.

I knew my Dad went out for pint in the local on a Saturday night and my Mum liked a Guinness—she believed the advertising that it was good for her—but I had never seen or heard of either of them having too much to drink, even at Christmas or family parties. It never crossed my mind that my quiet and very conventional parents, who cared a great deal about keeping up appearances, would ever risk getting drunk. So it was the thought of them merrily weaving home from the pub, with my Dad pushing my Mum in a wheelbarrow, that brought home to me the realization that something truly significant had happened.

If further confirmation was needed that historic events were taking place it came shortly afterwards when I arrived home from school to find a glass bowl in the middle of the dining table containing three curious curved yellow tubes. My older sister, who knew about such things, announced that they were bananas. That evening my mother peeled one of the exotic tubes and my sister and I shared the literal fruits of victory. I declared it to be delicious, although actually I was a bit disappointed.

Two days after VE Day, there was a party on our street. We lived in a working-class neighbourhood on the east side of London, but my Dad was a white-collar clerk and we aspired to middle-class values. Consequently I was the only boy present wearing a tie. I know this because I have still got the black and white group picture of our scruffy little group. There I am, sitting cross-legged in the front row, still apparently unable to grasp the victory concept. All the other kids are giving the victory sign in the approved Churchillian fashion; I, alone, have got it the wrong way round and appear to be making a very rude gesture at the photographer.

Years later, whenever the family got together, my mother, whose name was Queenie, would be teased about VE night: ‘I don’t suppose you remember much about that night, do you, Queen? You know, that night they brought you home in a wheelbarrow.’ My mother would blush and pretend to be cross, but I always had the feeling she was secretly rather proud that she had celebrated the end of the war in Europe with such ostentatious and uncharacteristic abandon.

Interviewing people for this book reminded me very forcibly of how different times were then, how curiously innocent life was. Everyone knew, beyond any shadow of doubt, that we were involved in a just war. The issues were clear: we were fighting on the side of good against the forces of evil, therefore we must, in the end, win. Whatever the price that had to be paid, whatever sacrifices it required, it was worth it. No war has ever been fought so unequivocally.

If anyone did harbour any doubts about the Allied cause, or the necessity for war, they were surely swept away when, in April 1945, the first reports began filtering back to Britain of the discovery of the concentration camps. Most people knew about the existence of the camps, and something of the Nazi persecution of the Jews, but until the advancing Allies had overrun places like Belsen and Dachau and Nordhausen, no one appreciated the sheer scale of the horror. Here, alone, was justification for the war.

A few days later came news of the death of Hitler. By then everyone guessed the end was near and that it was only a question of time before the war in Europe would conclude in victory for the Allies. There was still the war against Japan to be won, but peace in Europe was the first priority. The days of waiting were tense but, like the times, strangely disciplined. Even though we knew the Germans had surrendered on Lüneburg Heath, we waited patiently for the official declaration of VE Day and for permission to celebrate.

When it came there was an outpouring of rejoicing and relief and patriotism, the like of which the world will never see again. In these depressing days of social decay and drugs and violence, when large public gatherings frequently end in pitched battles with the police, it is hard to imagine that thousands and thousands of people jammed the streets of London well into the night on 8 May 1945 and those who were there, in that swirling mass of humanity, remember it as an unforgettable experience, one of the happiest days of their lives.

The most common crime of the night was to knock a policeman’s helmet off; the most frequent act of vandalism was to climb a lamp post.

Total strangers linked arms in the comradeship of their happiness, kissing and hugging was the order of the night, there was dancing on the streets whenever and wherever space could be found, when the crowd was not singing it was cheering, when it was not cheering it was laughing. The pubs ran dry, but who cared? This was a celebration driven by communal joy; no other stimulants were needed.

There were similar scenes in other cities around the world, in Paris, New York, Melbourne, Copenhagen … In rural areas, village communities lit huge bonfires and danced around the flames … And everywhere people drew back their curtains and let their lights blaze out into the night to mark the end of the blackout.

No, there will never be another day like it.

1

Tuesday 1 May

The Death of Hitler

At 10.30 p.m. on the evening of Tuesday 1 May 1945 the familiar voice of Stuart Hibberd interrupted a programme from Glasgow, called ‘Piping’ on the BBC’s Home Service: ‘This is London calling. Here is a newsflash. The German radio has just announced that Hitler is dead. I repeat, the German radio has just announced that Hitler is dead.’1

There was no further comment, no speculation about whether or not the report was correct and no change to the normal schedule of programmes. ‘Evening Prayers’ followed immediately after the announcement.

Elsie Brown regularly listened to ‘Evening Prayers’ and was making a cup of tea in her terraced house in East London. ‘I never missed “Evening Prayers” because my husband, Bert, was in the artillery somewhere in Germany and, it’s silly I know, but I thought that “Evening Prayers” was a way of staying in touch with him. I imagined him, wherever he was, listening too and thinking about home. ’Course I didn’t even know if they broadcast it over there; probably they didn’t.

‘Anyway, this night I was still warming the pot when I heard the news that Hitler was dead. At first I didn’t believe it, then I thought, well, it’s on the BBC so it must be true. I didn’t know what to do. I wanted to tell someone, but both the kids were asleep and I didn’t want to wake them, so I decided to run next door. My neighbour, Vi, worked the late shift on the buses and was always up till after midnight so I went round and banged on her door and when she opened it I shouted something like “He’s dead, the old bugger’s dead!” And she said, “What old bugger? Alfie?” Alfie was an old bloke who lived at the end of our road and really was a miserable old bugger, always shouting at the kids. So I said, “No, not Alfie, Adolf!”

‘When the penny dropped Vi said, “Here, Else, you better come in” but I couldn’t because I’d left the kids asleep, so she came back with me and brought a bottle of Guinness she’d been saving for a special occasion and we shared it. Of course we didn’t know any more than we’d heard, but Vi agreed with me that as it was on the BBC it must be true. She said, “Do you think it’ll all be over soon now?” I think I nodded and I remember I suddenly started crying. I don’t know why; I couldn’t stop.’

It was shortly before 9 that evening when Radio Hamburg interrupted a concert of the works of Wagner and Weber to ask listeners to stand by for a ‘government announcement’ to be broadcast at nine o’clock.

Nine o’clock came and went without an announcement but at 9.30 the broadcast was interrupted again: ‘Achtung! Achtung! In a short time German Rundfunk will broadcast a grave and important announcement to the German people.’ The German people could perhaps be forgiven for wondering what could be more grave or important than the fact that they were facing certain defeat after a senseless war lasting nearly six years and costing some five million German lives. They were to wait several minutes to find out.

At 9.42 another stand-by warning was repeated during a performance of Wagner’s Götterdaemmerung. At 9.47 there was another warning, with the assurance that the announcement would be made ‘in a few moments’. This was followed by the slow movement of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, written to commemorate the death of Wagner.

Bruckner gave way to funereal dirges and a drum roll from a massed military band. At 10.25 an unknown announcer came to the microphone, his voice choking with emotion: ‘It is reported from our Führer’s headquarters that our Führer, Adolf Hitler, has fallen this afternoon at his command post in the Reich Chancellery, fighting to the last breath against Bolshevism and for Germany. On Monday the Führer appointed Grand Admiral Dönitz as his successor. Our new Führer will speak to the German people.’

Listeners were offered little time to ponder the mystery of Hitler’s extraordinary prescience in appointing a surprise successor 24 hours before he fell in battle. For after another roll of drums Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander-in-chief of the German Navy, came on the air: ‘German men and women, soldiers of the German Wehrmacht! Our Führer, Adolf Hitler, has fallen. The German people bow in deepest mourning and veneration. He recognized beforehand the terrible danger of Bolshevism and devoted his life to fighting it.

‘At the end of this, his battle, and of his unswerving, straight path of life, stands his death, as a hero in the capital of the Reich. All his life meant service to the German people. His battle against the Bolshevik flood benefited not only Europe but the whole world.

‘The Führer has appointed me as his successor. Fully conscious of the responsibility, I take over the leadership of the German people at this fateful hour.

‘It is my first task to save the German people from destruction by the Bolsheviks and it is only to achieve this that the fight continues. As long as the Americans and the British hamper us from reaching this end we shall fight and defend ourselves against them as well. The British and Americans do not fight for the interests of their own people, but for the spreading of Bolshevism.

‘What the German people have achieved and suffered is unique in history. In the coming times of distress of our people I shall do my utmost to make life bearable for our brave women, men and children … ’

Immediately after his speech, an announcer read out Dönitz’s mawkish Order of the Day to the German armed forces: ‘German Wehrmacht, my comrades. The Führer has fallen. He fell faithful to his great ideal to save the people of Europe from Bolshevism. He staked his life and died the death of a hero. With his passing, one of the greatest heroes of German history has passed away. In proud reverence and sorrow we lower our flags before him … ’

During the statement, some listeners heard a faint ‘ghost voice’ which had somehow managed to hi-jack the wavelength. As the announcer read the passage about Hitler falling as a hero, an unknown voice materialized out of the ether and said simply ‘All lies!’

It was, indeed, uniquely appropriate that the German people should be fed a tissue of lies to mark the passing of the man who had caused them so much terrible sorrow. It was an act of extraordinary delusion to describe the Second World War as a struggle against Bolshevism in which Germany was the innocent and injured party, bravely battling to ‘save the peoples of Europe’. Neither did Hitler fall heroically at the head of his troops, fighting to the last breath against Bolshevism. On the contrary, he took the coward’s way out, locked himself in his quarters in the bunker under the Chancellery in Berlin, put the barrel of a revolver in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

The Führer had made his last public appearance on 20 April 1945, his 56th birthday. Wrapped in a greatcoat, smiling grimly, he inspected a pathetic little parade of SS troops and Hitler Jugend in the Chancellery garden. In the far distance could be heard the boom-boom of heavy artillery as Soviet troops breached the defence perimeter around the outer suburbs of the city. Hitler walked up and down the line of troops, stopped briefly to talk to a small, solemn boy in the black uniform of the Hitler Jugend, then disappeared through the steel door leading into the bunker and the fantasy world from which he now conducted the war.

On the following day, the Red Army’s 6th Tank Corps overran the German High Command’s abandoned headquarters at Zossen, south of Berlin. Increasingly deranged, Hitler seemed incapable of understanding the catastrophe inexorably engulfing him and from the bunker he continued to issue a stream of orders to generals of armies that no longer existed. General Karl Koller, chief of staff of the Luftwaffe, spent the entire day fielding calls from the Führer: ‘In the evening between 8.30 and 9 he is again on the telephone. [He says] “The Reich Marshal [Göring] is maintaining a private army in Karinhall. Dissolve it at once and place it under SS Obergruppenführer Steiner” and he hangs up. I am still considering what this is supposed to mean when Hitler calls again: “Every available air force man in the area between Berlin and the coast as far as Stettin and Hamburg is to be thrown into the attack I have ordered in the north-east of Berlin”. There is no answer to my question of where the attack is supposed to take place—he has already hung up.’2

Forty-eight hours after the Führer’s birthday, Berlin was cut off on three sides and Soviet tanks had been seen to the west of the shattered city. For Berliners the situation was desperate: after the Allies’ massive bombing raids, there was no water or electricity, food supplies were almost exhausted and public order was breaking down. Looters ransacked the huge Karstadt department store in the centre of the city, undeterred by SS troops with orders to shoot on sight anyone suspected of looting.

A young Berliner, a clerk by the name of Claus Fuhrmann, wrote a graphic account of life in the beleaguered city:

‘Panic had reached its peak in the city. Hordes of soldiers stationed in Berlin deserted and were shot on the spot or hanged on the nearest tree. A few clad only in underclothes were dangling on a tree quite near our house. On their chests they had placards reading: “We betrayed the Führer.”

‘The SS men went into underground stations, picked out among the sheltering crowds a few men whose faces they did not like, and shot them there and then. The scourge of our district was a small one-legged Hauptscharführer of the SS who stumped through the streets on crutches, a machine-pistol at the ready, followed by his men. Anyone he didn’t like the look of he instantly shot. The gang went down cellars at random and dragged all the men outside, giving them rifles and ordered them straight to the front. Anyone who hesitated was shot. The front was only a few streets away.

‘Everything had run out. The only water was in the cellar of a house several streets away. To get bread one had to join a queue of hundreds, grotesquely adorned with steel helmets, outside the baker’s shop at 3 a.m. At 5 a.m. the Russian [artillery] started and continued uninterruptedly until nine or ten. The crowded mass outside the baker’s shop pressed closely against the walls, but no one moved from his place. Often hours of queueing had been spent in vain; the bread was sold out before one reached the shop. Russian low-flying wooden biplanes machine-gunned people as they stood apathetically in their queues and took a terrible toll of the waiting crowds. In every street dead bodies were left lying where they had fallen.

‘At the last moment the shopkeepers who had been jealously hoarding their stocks, not knowing how much longer they would be allowed to, now began to sell them. A salvo of heavy calibre shells tore to pieces hundreds of women who were waiting in the market hall. Dead and wounded alike were flung onto wheelbarrows and carted away. The surviving women continued to wait, patient, resigned, sullen, until they had finished their miserable shopping.

‘We left the cellar at longer and longer intervals and often we could not tell whether it was night or day. The Russians drew nearer; they advanced through the underground railway tunnels, armed with flamethrowers; their advance snipers had taken up positions quite near us; and their shots ricocheted off the houses opposite. Exhausted German soldiers would stumble in and beg for water—they were practically children. I remember one with a pale, quivering face who said “We shall do it all right; we’ll make our way to the north-west yet”. But his eyes belied his words and he looked at me despairingly. What he wanted to say was: “Hide me, give me shelter. I’ve had enough of it.” I should have liked to help him, but neither of us dared speak; each might have shot the other as a “defeatist”.’3

On the afternoon of 25 April at Torgau, on the river Elbe, 75 miles from Berlin, a patrol from the US 69th Infantry Division, advancing from the west, ran into a patrol from the Russian 58th Guards Rifle Division, advancing from the east. By then Berlin was completely encircled by eight Soviet armies, which were smashing through the city’s feeble defences towards the Chancellery.

The diary of an anonymous German staff officer records the last days:

‘April 26. The night sky is fiery red. Heavy shelling. Otherwise a terrible silence. We are sniped at from many houses … About 5.30 a.m. another grinding artillery barrage. The Russians attack. We have to retreat again, fighting for street after street … New command post in the subway tunnels under Anhalt railway station. The station looks like an armed camp. Women and children huddling in niches and corners and listening for the sounds of battle.

‘Shells hit the roofs, cement is crumbling from the ceiling … People are fighting round the ladders that ran through air shafts up to the street. Water comes rushing through the tunnels. The crowds get panicky, stumble and fall over rails and sleepers. Children and wounded are deserted, people are trampled to death …

‘April 27. Continuous attack throughout the night. Increasing signs of dissolution. In the Chancellery, they say, everybody is more certain of final victory than ever before. Hardly any communications among troops, excepting a few regular battalions equipped with radio posts. Telephone cables are shot to pieces. Physical conditions are indescribable. No rest, no relief. No regular food, hardly any bread. We get water from the tunnels and filter it. The whole large expanse of Potsdamer Platz is a waste of ruins. Masses of damaged vehicles, half-smashed trailers of the ambulances with the wounded still in them. Dead people everywhere, many of them frightfully cut up by tanks and trucks … We cannot hold our present position. At four o’clock in the morning we retreat through the underground railway tunnels. In the tunnels next to ours, the Russians march in the opposite direction to the positions we have just lost … ’4

Hitler was already preparing for the end. In the early hours of 29 April, in a maudlin little ceremony conducted by an official of the Propaganda Ministry, he married his mistress, Eva Braun. Some time during the morning the latest news from the outside world was brought in. It was bad: the German forces in Italy were in full retreat and Mussolini, his partner in crime, had been captured and summarily executed by partisans. The Führer was probably not told that Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci, had been suspended by their heels from the roof of a garage in Milan to be mutilated and spat on by a jeering crowd, but in any case he had already made certain that no such fate should befall him and Eva Braun. His instructions were that their bodies were to be destroyed ‘so that nothing remains’, adding, as if anticipating the fate of his friend the Duce, ‘I will not fall into the hands of an enemy who requires a new spectacle to divert his hysterical masses.’

In the afternoon, Hitler summoned his personal surgeon to the bunker. The doctor was busy treating the many civilians wounded by shellfire but he could not, of course, ignore a summons from the Führer. When he arrived, Hitler ordered the doctor to administer poison to his favourite Alsatian, Blondi.

Later in the afternoon the Führer dictated his final messages, which included a last, bitter plea for his persecution of the Jews to continue: ‘I charge the leaders of the nation and those under them to scrupulous observance of the laws of race and to merciless opposition to the universal poisoner of all peoples, international Jewry.’ For his generals, whom he blamed for the defeat, he had stinging words: ‘The people and the Wehrmacht have given their all in this long and hard struggle. The sacrifice has been enormous. But my trust has been misused by many people. Disloyalty and betrayal have undermined resistance throughout the war. It was therefore not granted to me to lead the people to victory. The Army General Staff cannot be compared with the General Staff of the First World War. Its achievements were far behind those of the fighting front.’

Hitler thanked his two secretaries, praised their courage and added, characteristically, that he wished his generals had been as reliable as they were. He then gave them each a poison capsule for use, in extremis, and apologized that he could not offer a better parting gift.

SS guards had warned all the Führer’s personal staff that they were not to go to bed that night until orders had been received that they could do so. At half past two in the morning of 30 April, the staff were instructed to assemble in the bunker’s dining room so that the Führer could say goodbye. Some 20 officers and women staff were lined up along the wall when Hitler entered from his private quarters, accompanied by Martin Bormann. The Führer seemed distracted, his eyes were glazed over and some who saw him assumed he was drugged. He walked down the line shaking each person by the hand, sometimes mumbling inaudibly but generally saying nothing.

Later that morning, Hitler received reports without emotion that the Russians were closing in on the Chancellery. After lunch, there was another brief farewell ceremony with those senior officers still remaining in the bunker and their wives. Hitler and Eva Braun shook hands with each of them and then returned to their own suite. Shortly before 3.30, a single shot was heard. After an interval of a few minutes, an aide entered the suite and discovered the bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun lying side by side on a blood-soaked sofa. Hitler had shot himself through the mouth with a revolver; Eva Braun had apparently taken poison.

In accordance with the Führer’s orders, SS guards carried the bodies out of the bunker and laid them in the garden. With the fearsome cacophony of battle all around, the bodies were splashed with petrol from a jerry can, watched by mourners sheltering from the Russian bombardment under a porch. A petrol-soaked rag was lit and flung onto the corpses, which were instantly enveloped in flames.

On the evening of the following day, 1 May, with the fall of the city imminent, the bunker itself was set on fire and its 500 occupants dispersed as best they could through burning streets littered with rubble and bodies as the Third Reich neared its inglorious end.

‘We are in the Aquarium,’ the unknown German staff officer wrote in his diary. ‘Shell crater on shell crater every way I look. The streets are steaming. The smell of the dead is at times unbearable … Afternoon. We have to retreat. We put the wounded in the last armoured car we have left. All told, the division now have five tanks and four field guns. Late in the afternoon, new rumours that Hitler is dead, that surrender is being discussed. That is all. The civilians want to know whether we will break out of Berlin. If we do, they want to join us … The Russians continue to advance underground and then come up from the tunnels somewhere behind our lines. In the intervals between the firing, we can hear the screaming of the civilians in the tunnels. Pressure is getting too heavy … We have to retreat again … No more anaesthetics. Every so often, women burst out of a cellar, their fists pressed over their tears, because they cannot stand the screaming of the wounded.’5

That afternoon, William Joyce, the notorious ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ whose ‘Germany Calling’ broadcasts had provoked such fury in Britain, recorded his last talk, apparently roaring drunk. ‘We are nearing the end of one phase in Europe’s history,’ he said, his voice noticeably slurred, ‘but the next will be no happier. It will be grimmer, harder and perhaps bloodier. And now, I ask you earnestly, can Britain survive? I am profoundly convinced that without German help she cannot … ’ There was a long pause, then he seemed to admit that it was all over. ‘You may not hear from me again for a few months … Germany is, if you will, not any more a chief factor in Europe.’ After another long pause, he made a final gesture of defiance, booming: ‘Es lebe Deutschland … Heil Hitler. And farewell.’6

Vladimir Rubinstein was an Estonian working for the BBC monitoring service at Evesham in Worcestershire: ‘Towards the end of the war we were all so anxious to see what was going to happen that everybody was just sitting and waiting in the listening room for any kind of indication. In the last ten days of April, the whole enemy-controlled radio network in Europe began to disintegrate and split up into regional services with their own programmes.

‘On 30 April, there was an announcement suddenly by two of the radio services, the south-western and the south-eastern services, I think, saying a very, very important statement was going to be broadcast tonight. There was terrific excitement and all the staff began to come in from other departments and collect in the listening room. The whole listening room was full and extremely noisy and we repeatedly had to say to them, “Shut up, for God’s sake!” because nobody could hear anything. We had no idea what it was going to be about, just that it was extremely important.

‘People were milling around, all waiting, and nothing happened! We sat and sat and absolutely nothing occurred. There was supposed to be something by 11 o’clock in the evening and still nothing happened. So the whole thing was a flop. Nothing happened, so everybody dispersed.

‘Then the next day one of the people working in the monitoring service was Sir Ernst Gombrich, the famous art historian. It was towards evening and he suddenly realized that the radio had started playing a Bruckner symphony, very solemn music. He said, “That seems very strange” and started to prepare himself. In those days, when you monitored a broadcast, if you had something very urgent, to avoid leaving the set unattended, you would write it down on a bit of paper and give it to the next person to run off to either the news bureau or information bureau, from where it was teleprinted or telephoned straight through to No 10 Downing St or the War Office.

‘So Gombrich prepared two or three notes for himself, alternative things that he thought might happen: Hitler dead, Hitler taken prisoner, or Hitler escapes. Then there came the announcement, and while everybody held their breath Gombrich picked up the “Hitler dead” note.’

Harold Nicolson MP was dining at his club, Prat’s. ‘Lionel Berry [son of Lord Kemsley] was there,’ he wrote in a letter to his son, Nigel. ‘He told us that the German wireless had been putting out Achtungs about an ernste wichtige Meldung, and playing dirges in between. So we tried and failed to get the German wireless stations with the horrible little set which is all that Prat’s can produce. Having failed to do this, we asked Lionel to go upstairs to telephone one of his numerous newspapers, and he came running down again (it was 10.40) to say that Hitler was dead and Dönitz had been appointed his successor. Then … I returned to King’s Bench Walk and listened to the German midnight news. It was all too true. ‘Unser Führer, Adolf Hitler, ist … and then a long digression about heroism and the ruin of Berlin … gefallen.’ So that was Mussolini and Hitler within two days. Not bad as bags go.’7

Inevitably, the news of Hitler’s death made banner headlines in all the morning newspapers the following day, along with encouraging reports from the front of the Allies’ progress. Russians troops were said to be at the Brandenburg Gate in the centre of Berlin, having taken 14,000 prisoners in the previous day’s fighting. The British Second Army was only 18 miles from Lübeck and poised to cut off the enemy’s only escape route from the advancing Russians. The American Seventh Army had cleared Munich and was pushing into the Austrian Alpine passes while the US Third Army had reached the Czech frontier.

Such was the mood of confidence in the country, that all the newspapers also reported the progress of the arrangements for VE Day, in particular a circular letter issued by the Home Office expressing the government’s sober views on the form that national celebrations should take. It was a poignant reflection of the austerity that still went hand in hand with victory:

‘His Majesty’s Government have had under consideration the way in which the defeat of the enemy in Europe should be celebrated. The end of the war in Europe will not be the end of the struggle and there should be no relaxation of the national effort until the war in the Far East has been won. It will, however, be the general desire of the nation to celebrate the victorious end of the European campaigns before turning with renewed energy to the completion of the tasks before it.

‘Accordingly, as already announced, the day on which the cessation of organized resistance is announced, which will generally be known as VE Day and the day following, will be public holidays … The cessation of hostilities in Europe will be announced by the Prime Minister over the wireless and His Majesty the King will address his people throughout the world at nine pm the same day. It is the wish of his Majesty the King that the Sunday following VE Day should be observed as a day of thanksgiving and prayer.

‘In view of the shortage of fuel, materials and labour, it is still necessary to observe economy in the consumption of fuel and light and the government regret that they will not be able, even on VE Day, to agree to the restoration of full street lighting.

‘Except in the coastal areas in which dim-out or black-out restrictions are still maintained, they will, however, raise no objection to the use on the VE night or the succeeding night by local authorities and public bodies of such flood-lighting facilities as exist and can be brought into use. In addition, the Armed Forces will make available for illumination purposes such lighting as can be spared.

‘Bonfires will be allowed, but the government trust that the paramount necessity of ensuring that only material with no salvage value is used and the desirability of proper arrangements with the National Fire Service to guard against any possible spread of fire will be borne in mind by those arranging bonfires.

‘In view of the pressure on public transport generally throughout the country it seems to the government desirable that facilities for indoor entertainment should be available as widely as possible. They would not suggest that theatres, music halls and cinemas should remain open later than the hours prevailing before VE Day, but, provided that adequate staffs can be made available, they hope that the managements of theatres, music halls and cinemas will keep their premises open until the usual hour.

‘As regards premises licensed for public dancing, the government think that these might be allowed to remain open later than the normal closing hour … ’

Pub landlords throughout the country were obviously anticipating big business on VE Day, since the circular letter continued: ‘Licensing authorities for the sale of intoxicating liquors are already receiving applications from licence holders for special orders of exemption, or special permission in respect of VE Day, from the requirements as to permitted hours. His Majesty’s government suggest that advance individual applications for special orders of exemption or special permission for an extension of the evening permitted hours on VE Day should receive sympathetic consideration in the light of local circumstances … ’

However, such aberrant behaviour as drinking in the afternoon was certainly not to be countenanced in a country which considered such Gallic habits to be especially sinful, and neither would any relaxation in the licensing laws extend beyond VE Day. ‘No exemptions should be granted in respect of the afternoon “break”, nor should applications be entertained in general for any special order of exemption or special permission on the day following VE Day.

‘So that the essential requirements of the public be met, the government recommend that businesses selling and distributing food should remain open for a few hours on VE Day to enable the public to get supplies and, subject to maintaining the sale or delivery of essential commodities such as bread, milk and rations, close on the following day. They appreciate this will mean some inconvenience to those engaged in these essential services, though it is understood holidays in lieu will be granted under trade agreements.

‘On Thanksgiving Sunday His Majesty’s government think it appropriate that local authorities should organize victory parades either with the local service of thanksgiving or later in the day.

‘In addition to such representation of the Armed Forces as can be arranged with the local commander, the local authorities will no doubt wish to include all those associated with the wide range of the Civil Defence Services, the National Fire Service, the Fire Guard, the Police, the Women’s Land Army, war workers of all categories, and members of various youth organizations and voluntary societies.’ 8

No such preparations were, it seemed, being made in the United States. On the same day the disbelieving British were being told that the pubs could stay open to midnight on VE Day, that the London County Council was organizing floodlit dancing in no less than eight different parks and that hundreds of London policemen had been put on stand-by for extra duty on the great day, in Washington President Truman expressed the hope that there would be no celebrations in the United States, only a ‘national understanding of the importance of the job which remains’. The White House issued a statement promising that the President would address the nation over the radio ‘in the event of the end of the war in Europe’, but emphasized that the statement was not intended to suggest that the end was imminent.

It was a curious reversal of the commonly accepted characteristics of each nation. The Americans had become unusually guarded and cautious; the British had become infected with the kind of heady optimism frequently found across the Atlantic.

For most people, the death of Hitler was another nail driven firmly in the coffin of the Reich, although considerable sceptism remained. It was understandable enough: in the previous six months there had been frequent rumours that the Führer was dead, only to be scotched by his strutting appearance at a Nazi rally or some other public function where those present could attest that he was all too alive. One in four of the people questioned by Mass Observation stated simply that they did not believe Hitler was dead. Many of them ventured the view that it was part of some dastardly plot to help him escape:

‘Saying Hitler’s dead and playing a funeral march over the radio, I don’t believe that tale, do you? The papers talk as if he was, but I think it’s more likely a lie while he gets away. The more you think it over the more it sounds all wrong.’

‘What again? I’m fed up with hearing that bloke’s dead.’

‘I don’t believe he’s dead at all. He’s hidden away in the mountains, and he’ll come out again in a few years’ time, and start another war … He’ll find a way, he’s cunning. We haven’t heard the last of him, you’ll see.’

Even those inclined to believe that the Führer had departed this life, suspected that there was probably some chicanery involved:

‘I think if he is dead, he died when there was that attempt on his life. But he’s got five doubles, you see, so that you can’t quite tell.’

‘I don’t believe he died fighting. They just said that to make it seem more, you know, the way he’d have wanted people to think he died. But I think personally he’s been out of the way for a long time now. The last time he spoke he didn’t sound the same man at all. He sounded very ill. I think he’s been dead for a long time now, or at at least too ill to count for anything.’

A considerable number of respondents offered the opinion that death was ‘far too good’ for someone like Adolf and described in lurid detail what they would like to have done to him had they had the opportunity to get their hands on him. Many of the most bloodthirsty accounts came from women:

‘It’s too good a death for him, that’s all I can say. If I’d had my hands on him he wouldn’t have died that easy. I wouldn’t have finished him off quickly like that, I’d have cut off little bits of him, one at a time, until he was dead.’

What most of the sceptics wanted was evidence:

‘They say Hitler’s dying. What I want to know is, who says so? How do we know it’s Hitler? Whose word can we trust? They said weeks ago that he was going to fly to South America. I won’t believe that man’s dead until I see his dead body on the pictures.’

‘Ooh, the rumours! Hitler’s dead. Hitler’s not dead but he’s dying. Hitler’s only having his face lifted. Some people say Churchill will announce peace on the nine o’clock news tonight. Oh, they’re saying everything! My ears are dropping off with the rumours I’ve heard. The one thing you can take for certain is that Mussolini’s dead.’9

That was undeniably true, because the newspapers on the morning of Tuesday 1 May were full of grisly pictures of his body, and that of his mistress, hanging upside down in Milan for the ghoulish entertainment of passers-by.

Harold Nicolson was among many who found the pictures thoroughly distasteful: ‘We had really dreadful photographs of his [Mussolini’s] corpse and that of his mistress hanging upside down and side by side. They looked like turkeys hanging outside a poulterer’s: the slim legs of his mistress and the huge stomach of Mussolini could both be detected. It was a most unpleasant picture and caused a grave reaction in his favour. It was truly ignominious—but Mrs Groves [Nicolson’s housekeeper] said that he deserved it thoroughly, “a married man like that driving about in a car with his mistress”.’ 10

Clara Petacci was a curious focus of people’s interest, although there was precious little sympathy either for her or her lover:

‘There was a wonderful account in the Daily Worker of Mussolini’s death, how he was shot in the head and his brain spattered out, and he looked awful, but his mistress was hanged beside him in a new white blouse and looked lovely.’

‘Some woman in the office looked at a picture of Mussolini’s death and all she said was “Nice legs, hasn’t she?”’

Those who professed to be shocked were not so much disgusted by the deaths as by the reaction of the Italians:

‘I was absolutely horrified about the Italians, the way they took revenge on Mussolini. I can’t imagine what we’re fighting for, if that’s the way the anti-Fascists behave. I was just reading in the paper that they hung them up in the most lewd, indecent positions, and spat at them, and threw stones. And laughed. The Italian people don’t seem to feel any horror at this either. I think it is just too ghastly for words.’11

Briefly among the crowd jeering and spitting at the bodies was a 19-year-old captain in the Devonshire Regiment by the name of Alan Whicker, who would later make a considerable name for himself as a television personality. In May 1945, Whicker was attached to an Army Film and Photo Section in Italy and he remembers the day of Mussolini’s death as pretty hectic:

‘I had a marvellous big Italian car that I had liberated after the capture of Rome and myself and a couple of sergeants drove across the Apennines into Verona and Milan. I think we were the first people into Milan and we got a reasonably enthusiastic reception as we drove into the cathedral square, although there weren’t a lot of people about because they thought there was going to be a lot of fighting.

‘The first thing that happened in the square in front of the Duomo was some partisans came up in a great state of excitement. All these chaps emerge from the long grass as soon as the fuss is over and they said there was a hotel full of Germans just round the corner. They were the last Germans in Milan and they were refusing to surrender to the partisans, not unreasonably I suppose. They were insisting on surrendering to an Allied officer, and as I was the only one around I thought I better go there.

‘I followed the partisans down a road, not too far from La Scala, and there was this bloody great hotel surrounded by barbed wire and armed SS guards. The general in command who was insisting he would only surrender to an Allied officer was rather disappointed when he saw my lowly rank. Nevertheless, he presented me with his Walther revolver and surrendered the hotel full of SS men. He could speak good English and said he didn’t want to surrender to “this rabble”, indicating the partisans who were shouting and getting very excited on the other side of the barbed wire. I must say I had a sneaking sympathy for him. I didn’t bother to disarm them, I mean for them the war was over and I could see they were finished, but they were very anxious to show me things and made a lot of fuss about handing over a tin box, which didn’t interest me very much because I had other worries on my mind. But when we opened the box we found it was full of money, every known banknote you can imagine. I thought, my God I could be a mega millionaire. I don’t know where the money came from and I never did discover what happened to it.

‘I knew there were some American troops arriving soon because we had overtaken them as we were driving in, so I just accepted the surrender and waited. After two or three hours some American tanks arrived and I handed my hotel full of SS men over to them.

‘Afterwards I went to a radio station and asked them to put out a call for John Amery. Amery was the son of Leopold Amery, the secretary of state for India, and was the Lord Haw Haw of Italy. During war he had been the traitorous voice of Fascism. A message went out and within half an hour I got a call from a chap in charge of a jail who said that Amery had been arrested and was in his prison. I went over there. He was with his very pretty Italian girl friend and was very grateful I arrived because he thought he was going to be killed by the partisans. Before I arranged to hand him over to the military police I had a talk with him. He said, “I’ve never been anti-British, you can read the scripts of my broadcasts over years and you’ll never find anything anti-British; I am just very anti-Communist. At the moment maybe I’ve been proved wrong, but in the future you may think I was right.” He was a pleasant, intelligent man. After he was repatriated to Britain, he stood trial at the Old Bailey for treason, was convicted and hanged.

‘Later that day we discovered Mussolini had been shot and hung up in a garage with his girl friend. We went over there and took pictures of them. A Milanese mob was baying, spitting and screaming at the bodies. I still have a terrible picture of Mussolini hanging upside down in that garage.

‘Although the war was virtually at an end in Italy, everything was all falling to pieces and they were all giving up everywhere. I don’t remember celebrating at all. There was a very exhilarating spirit because one was alive after having been through some very hairy times, but one was too busy to celebrate. I just remember having a hell of a day and driving back to Verona to get all my pictures away. It was quite a crowded day for a 19-year-old.’

It was the pictures that convinced the world that Mussolini was dead and the lack of pictures that created such scepticism about the death of Hitler, at least in Britain. In Germany, people were eager to accept the news as an indication that their suffering would soon be over. Only a few die-hard Nazis would grieve over the passing of the Führer; most Germans experienced more relief than grief.

This was certainly the case for the British-born writer Christabel Bielenberg, who was living with her German husband, Peter, and their three sons in Rohrbach, an isolated village in the Black Forest. Peter Bielenberg had been in hiding, having been arrested after the failure of the bomb plot against Hitler in July 1944. He spent seven months in Ravensbrück and was then assigned to a punishment squad in the army, from which he had escaped to join his wife and family in Rohrbach.

By 1 May the area around Rohrbach was occupied by the Allies. Christabel described their reaction to Hitler’s death like this: ‘The news reached us as we sat around the stove in the gute Stube of the Gasthaus Adler listening to the wireless which was our only remaining link with the outside world. Since the arrival of the French in our little local town of Furtwangen, the Adler had recovered something of its pre-war repute and become once more a rallying point for many bewildered Rohrbach villagers, eager to pick up the latest rumour, eager if possible to hear the latest news, although Frau Muckle’s ancient contraption gurgling and whistling away in the corner seemed sometimes as confused as we were as to quite which programmes we were listening to. Allied? German? To which side did all those voices at present belong? Which version were we supposed to believe, as day by day more German townships, further chunks of German land were overrun, changed hands and passed under the control of American, British, Russian and French armies?

‘This time the wireless seemed certain of its message. (There had been plenty of rumours, but this was a certainty.) It gave no details as to where, how and when, but just crackled out something about Hitler (the Fuehrer), having first appointed Admiral Doenitz to be his successor, had made up his mind to die a hero’s death and had done so.

‘A sudden stillness came over the room as the message petered out along with the usual mechanical convulsions. Perhaps even the death of a devil casts a certain spell, for by force of habit some crossed themselves while others just stared at the stove, some took the odd sip from one of the lemonade bottles which Frau Muckle had managed to provide for our entertainment, others puffed on pipes filled with tobacco left behind by the departing German Wehrmacht. Only the measured clacking of the cuckoo clock on the wall behind us interrupted the silence …

‘So that was it; he was dead. Although bombers still droned occasionally overhead, reminding us that some parts of Germany still had to pass through the final ordeal, he, Hitler, was gone. It could not be long now before the coup de grâce, the final knock-out-blow, was administered to his mad dream of creating a Thousand Year Reich, empty of all but pure-bred Germans; round blond heads, glowing blue eyes, Aryans one and all, oh dear.