Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Archaeology isn't just for academics and television presenters – it's for everyone. And it is all around us. Get your boots on and explore Britain's national and local archaeology sites for yourself with this revised and updated, easy-to-read, fully illustrated guide. Follow our islands' history in this step-by-step introduction. Discover what life was like from the earliest days of human habitation right through to the world wars. Then get out to visit the best sites and see what features each era left behind for us to find – and find out how to spot archaeology for yourself in the most surprising places. Be warned: you may never look at an empty field, a stone monument or an old building in the same way again!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 306

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘A vibrant and engaging guide to history’s footprints’Your Family History – Seal of Approval (August 2009)

‘Richly illustrated throughout’‘An exceptionally well-written and accessible guide to archaeology’Walk, the Rambler’s Association magazine (Winter 2009)

‘An easy-to-follow, well-written guide’Dalesman

‘If you have a budding interest in archaeology then this book is for you’Harrogate Advertiser (16 October 2009)

To Helen for being fabulous

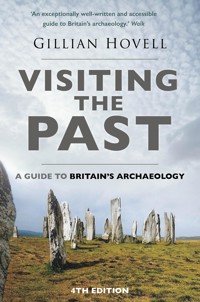

Front cover illustration: Callanish stones. (© Liz Forrest)

Back cover illustration: Hadrian’s Wall. (Unsplash/Toa Heftiba)

First published 2009

This revised and updated fourth edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Gillian Hovell, 2009, 2010, 2015, 2023

The right of Gillian Hovell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 273 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part I: Getting Started

What is Archaeology?

Archaeology Matters

Monumental History

Unravelling the Past

Spotting Hidden Archaeology

Part II: The Seven Ages of British Archaeology

The Essentials

Timeline

The Stone Age

The Bronze Age

The Iron Age

The Romans

The ‘Dark Ages’

The Medieval Ages

Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern Age

Part III: Digging Deeper

Kit Check

Basic Fieldcraft

Making a Difference: Recording and Reporting

A Helping Hand

Joining Up: Getting Involved

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

An archaeology guide is like reading a detective novel. You get to know the settings and the characters involved and then you start to piece together who did what, when and how. And, like in murder mystery tales, the best final denouements are gained when you get help and information from many different sources and witnesses. Writing an archaeology book is no different: the weaving together of its many threads into a coherent story is the result of support and guidance from many people.

In the first instance, my thanks go to professional archaeologist Kevin Cale, for his unflagging work in enabling and guiding the many community archaeology projects in the Nidderdale area in years past. Without his input and his teaching, and indeed his patience as he coped with my foolish questions, I would never have even started down the happy and satisfying road to archaeology.

In a similar vein, my eternal thanks go to all those who have given so much support and friendship over the years as we explored new archaeological ventures together. My special and eternal thanks go to Michael Thorman, who recently passed away; you regularly braved the elements and my company on any number of windswept hillsides and I shall never forget how you made archaeology such fun; even in horizontal rain and boggy fields we never fell out – instead we just fell about when I fell in. Archaeology is at its best when it’s not a lone activity. So, to my many friends over the years who have welcomed us onto their land and their sites, and with whom I have shared various projects, excavations, tours and cruises, talks, courses and events, publication epics and media moments, my grateful thanks.

Of course, I would never have done any of this without the unstinting encouragement from certain special folk in my formative years long ago: ‘Mrs Jones’, who read Tales of Greece and Rome to me when I was nine and started this whole fascination; Ros Hall (née Brown), who encouraged me, sharing an early enthusiasm for all things classical and quietly feeding an obsession that often seemed like madness to others; and my tutors at Exeter University, David Harvey and Professor Peter Wiseman in particular, who inspired my continuing love of ancient history.

Since then, those who have enabled and encouraged my passion for researching and sharing archaeology and ancient history are too many to mention, but I am forever grateful. Every event, every media moment, every discovery is only ever cherished because you are there too. The smiles and the laughter, the challenges, efforts and the successes are all ours to share.

On the writing side, I owe a debt of gratitude to so many: to Alex Gazzola, for all his support and encouragement as I started out so long ago on this writing enterprise; to generous suppliers of images; and to my army of proofreaders, who have been so lavish with their time as they scoured the manuscript. Of course, my thanks to The History Press for guiding me through the practicalities of it all, and to all the team there. And I look forward to new adventures, audiences and friends, as the journey continues forward, to keep digging deep into the past to add colour and depth to our lives today in so many ways.

Finally, this book could not have existed without my friends, who have cheered me on, and especially to my daughter, Helen, who has been by my side through everything, including and beyond the explorations and the writing. You indulged me as we repeatedly visited yet another archaeological ruin and squeezed in yet another detour to an ancient site. Thank you to you and to your brother, Mark, for smiling as you asked, as we set out on an inevitable walk while on holiday, ‘so tell us now: is the archaeology at the beginning, the middle or the end of this walk we’re going on?’ It was, of course, at all three points.

Gillian HovellJanuary 2023

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to the story of Britain. It’s a tale we’ve heard many times and in many ways, but this time it’s personal. This is history we can reach out to and touch for ourselves: it’s all around us, etched on our hillsides and filling our valleys. This is a journey to places you thought you knew, but with this book as a guide, you’ll have a new map to explore them with and a fresh viewpoint to see them from.

So just where are we going? Our route starts in the long-deserted homes of our prehistoric dawn. Soon it reaches the enigmatic standing stones, earthy mounds and stony-faced fortresses that once dominated the country. On our way we shall encounter generations of fresh settlers with new ideas who left behind a variety of atmospheric ruins, and we shall witness countless lives that shaped our countryside. We shall move on, through the belching power of industry as it forged its way across our landscape, until we pause at the battle-scarred land of the world wars. Our journey will take us across the length and breadth of Britain and through the millennia from mankind’s first steps on our soil to our own personal yesterdays.

This narrative of our islands is told through archaeology, that is, the physical remains left behind by our ancestors. Some of the ruins in our story are monumental and obvious. Take Stonehenge for example: we may not know everything there is to know about it, but it’s prehistoric, well-visited and pretty unmissable as monuments go.

Fig. 1. Stonehenge is an obvious example of British archaeology. (©The History Press Ltd)

While grand sites like Stonehenge make for great days out, if we look at them more closely – as archaeology – they can do so much more than simply entertain us for a few hours. A visit to an archaeological site is a visit into the past: every monument, every ruin and every sacred site tells a story. And even the very bones of our ancestors can paint a vivid picture for us of what their lives were like, if only we know where to look.

This book aims to share archaeology’s hidden clues and to help to unlock the secrets of our monuments, whether they be large or small, unimaginably ancient or more recent and numbingly familiar. World famous heritage sites and previously barely noticed lumps in anonymous fields all have their tales to tell. So, who is this book for? If you’re a complete novice, a TV history fan, a practised amateur archaeologist, or even a professional looking beyond your specialism, then this book is for you. If you enjoy walks in the country or like seeing a new point of view, then getting to grips with our islands’ archaeology is for you. All you need is reasonable eyesight, some sound footwear and a good dollop of curiosity. Take this book with you as you get out and explore Britain’s archaeology for yourself: see the great sites in a new light, or pop out for a local stroll and discover just how much silent history lurks around every corner.

First though, settle down to a little armchair travelling. Read on and discover how to visit the past and bring yesterday’s stories into our lives today.

WHAT IS ARCHAEOLOGY?

Let’s begin with that most basic question: what is archaeology? What do we think of when we talk of archaeology? Our first thoughts may be of vast ruins of conquering empires, hoards of treasure salvaged from the earth, or muddy holes in the ground surrounded by even muddier diggers (colour plate 1). These are the aspects of archaeology that dominate our screens and, surprisingly often, our news.

Yet there is another, far more intimate side to archaeology. That field at the end of your road, the building we work in or walk past every day and the hill that dominates the landscape may all contain a slice of history. Many people are surprised to discover that our lives are surrounded by archaeology. Even though we all live cheek by jowl with it, we rarely notice it. This book shares how archaeology (and the history it reveals) is as much a part of our lives as the buildings we call home and the roads we travel on today.

Of course, organic material usually decays and so all we are left with are just the stones, shadows of postholes, and a few artefacts such as pottery and metallic tools. It’s rather like being asked to describe a finished 5,000-piece jigsaw having been given no picture and fewer than fifty pieces in total. Yet that can be enough to know if your jigsaw is trying to recreate a photograph or a painting, a natural scene or an indoor scene, a human environment or a lunar landscape; you can get a general impression of the picture. And, in the same way, those tiny archaeological clues can tell us much more than you might imagine.

Today, there are many ways to examine those clues. Indeed, one of the fascinations of archaeology is that it is a multi-skilled discipline which opens the mind to evidence from all angles: laboratory analysis; fieldwork surveys on and under the ground or in rivers and lakes or under the sea; anthropological studies of present-day primitive cultures; macabre forensic science on long dead bodies; cutting edge DNA studies; reconstructive experimental archaeology; aerial photography … the list goes on. But there is one skill, which everyone can possess and which doesn’t require expensive kit, a science degree or a silly hat and trowel. That skill is typology, otherwise known as identifying artefacts and features from their particular style and shape. And it is this aspect of archaeology that this book concentrates on.

It is possible to recognise the probable age of a flint tool by its chunkiness or its size; we can spot potential burial mound dates by their shape, size and location; we can discover a likely Roman fort by the shape and layout of a few lumps in the ground; and we can identify the various possible ages of parts of a church by their architectural styles. Obviously, we cannot discover everything about an historic site simply by looking at it; excavation, analyses and the study of relevant historical documents are just some of the other elements which need to combine to tell us the true story. But it is a great starting point and, combined with just enough historical know-how, we can all begin to ‘read’ the landscape and monuments around us.

Fig. 2. The shape of this bump in the ground tells us that it may be a 5,000 year-old burial mound. (© Gillian Hovell)

ARCHAEOLOGY MATTERS

But why should we bother with the splintered ruins and fragmented remains that litter our landscape? Many would claim they matter because they are our heritage; and that makes us who we are today. Others would say they are precious because they are priceless and unique: a burial mound such as West Kennet Long Barrow, built over 5,000 years ago, can never, ever, be replaced once lost. Both are absolutely right, but we should never dismiss another, often forgotten, reason for treasuring our relics of the past; millions of us subconsciously acknowledge it when we take the family on a day out to a famous castle or walk the dog at the local abbey ruins. We instinctively do it because it’s fun and it feels good. It is no coincidence that some of our greatest tourist attractions are historic monuments: there is a basic and primeval satisfaction in rubbing shoulders with our ancestral roots (colour plate 2).

However, it is possible to take it a step further. Instead of simply mingling in an anonymous crowd of historical features, we can get to know them. Seeing those ruins from the past in a fresh, new way is truly thrilling: when we know what we’re looking at, a walk in the countryside becomes a personal trip through time as we pass a previously unremarked medieval field boundary, a trace of an Iron Age hut circle or a church which glories in centuries of alterations and additions. After reading this book you may never go for a walk and simply admire the view again: history will accompany you all the way.

Personally, I began my own addiction to history at the tender age of nine when a teacher called Mrs Jones breathlessly read to us from a slender blue volume that was just packed with stories from another time and a distant world. As I sat spellbound, I saw the world in a new, previously unimagined way; the tales of the past were full of people living in different circumstances and often obeying different social rules and yet they were just like us. I realised that life can be different but familiar at the same time and I came to realise that, by comparing our lives with those of others, we can see ourselves anew as part of one timeless family of humanity. Mrs Jones was reading to us the Tales of Greece and Rome but the same principle applies to any era in any country.

Decades later, I relished the days (and years) I spent unearthing fresh traces of our history while leading a local community archaeology project. For I simply cannot imagine a world without the thread of history running through it. It would be like trying to paint a picture of the present without having any canvas to work on: you would end up with nothing more than a sloppy, shapeless and globby mess on the carpet.

This book is designed to be that canvas, a basic tool on which you can add whatever tints and shades of history you come across. I want to share with you and spark an adventure of discovery, that increasing awareness that we are a living part of a coherent and ever-continuing story. By opening our eyes and really looking at the spaces we live and work in today, we can catch a glimpse of what it was like to be a person just like ourselves here in this place but in another time. For archaeology concerns the most fundamental topic of all – human life. It unearths echoes of past lives, of locals who worked and loved here day in, day out, and who died here too: the peasant tilling the heavy soil, the regular soldier on look-out from the fort or castle wall, the weary monk stumbling to Matins. We walk where they walked before us: we share their space, if not their time. Just sometimes it is the dignitary, the politician or the king who tramped the fields and the stone flagged floor, and they may have funded the building of monuments, castles and abbeys and probably visited them and feasted in splendour. But more often it is the stonemason patiently carving the block, the servant scurrying to serve the master, or the farmer scraping a living from his small enclosure whose living space we share by visiting the past. Doctor Who can transport us to other imagined times but archaeology is the nearest we can get to real time travel.

Archaeology aims to understand the past, but in doing so it also makes sense of the present. For that past created our present and we cannot know nor understand where we are going unless we know where we are coming from. Archaeology is not just the discovery of the material remains of the past, but the interpretation of how, why and when folk did what they did and made what they made: because human nature never changes, it can tell us how, why, and when folk are inspired to do things nowadays or even in the future. At a fundamental level therefore, archaeology tells us much about what makes us human. In fact, because it is the sole evidence for our prehistoric past, it is archaeology that provides our understanding of where all modern people came from and how our early societies developed. Archaeology is therefore crucial to the discovery and interpretation of our roots.

Fig. 3. St Margaret’s Church in Hales, Norfolk, takes us back 800 years to the time when the Normans ruled the land. Typical Norman details include the rounded apse. (© Andrew Hovell)

Some ages (especially those early millennia) have left behind very little evidence. Every find counts. Each one offers a unique flickering glimpse of a lost moment of time: the charred remains of a meal cooked over a particular fire on a particular day; a life lost to a thin arrowhead between the ribs at Iron Age Maiden Castle; even a letter home for more socks from a Roman soldier at Vindolanda fort on the frontier of his world. And, even as a slightest flicker can change the focus of a picture, so a single find can tweak our view of history and therefore our understanding of our heritage. This is part of the fun of archaeology: it is not a static, fixed science, but a continuing voyage of discovery. The bickering television archaeologists aren’t just arguing in order to make a more entertaining programme, they are comparing and disputing their latest theories. Archaeology thrives on controversy and debate because new finds and new theories open our eyes to fresh interpretations and ideas.

We all need to be aware that any and every find could help to write a fresh page in the history books. Any new find should therefore be shared with the central recorders of our islands’ history (the Heritage Offices and the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS)). Even a quick peek at the images on the PAS’s website, www.finds.org.uk, soon reveals how a single find adds material to an ever-growing and fascinating story.

So, it all matters. But let’s climb down off the soapbox and remember that archaeology has many personal benefits: it gets you out in the fresh air; it’s good exercise (physically and mentally); it can give you space for thought or to be sociable; it’s exciting, even entertaining; and it gives you a whole new perspective on the world. But, most of all, it’s fun, and anyone can do it.

MONUMENTAL HISTORY

Where should we start? We need to begin by recognising the different ages in Britain’s history. There’s a timeline to help us in Part II, but the briefest of summaries goes like this: nomadic prehistoric folk in Britain eventually settled down and then various opportunistic people poured in, including the Romans, followed by church missionaries, Angles, Saxons, Vikings and finally the Normans, in 1066, who kicked off the medieval period with bureaucracy and abbeys and castles galore. By 1500, the first glimmerings of a modern age can be glimpsed in a post-medieval era which grew into the industrial age and life as we now know it. That’s several thousand years in a nutshell, but how do we zoom in for a closer look at them?

To get a feel for any one era, pop into a museum dedicated to that age: several are listed in Part II. If you happen to be in England’s capital, an afternoon’s stroll around the Museum of London or the British Museum are excellent tasters for all the eras. In the latter, you can be alongside some of the major discoveries unearthed in Britain, such as prehistoric burial goods and glittering gold like the remarkable Bronze Age Mold Cape, a wheel from an Iron Age northern cart burial, Roman finds galore, and the dramatic Sutton Hoo riches. Undoubtedly, though, some of the best places to get to grips with these ages are the sites themselves. Start with those we are vaguely familiar with and which obviously belong to set eras in history: the distinctly prehistoric monuments or the grand Roman villas and forts; the early Christian communities or the later ruined medieval abbeys and castles, which are so much a part of our modern image of the countryside; or maybe the still solid foundations of the industrial age. Each era in our history has its share of these atmospheric and enlightening places, and the pick of the best of them is also set out in Part II.

Fig. 4. Castle Acre in Norfolk is a classic medieval castle. (© Andrew Hovell)

We are incredibly fortunate in Britain to have a vast wealth of excellent sites to visit. Fantastic places of real historic interest are restored, maintained and presented to us by national organisations such as English Heritage, Historic Environment Scotland, Wales’ CADW, Heritage Ireland and the National Trust for England and Scotland, as well as private trusts, professional archaeologists, land owners, lifelong devotees of particular sites, a vast and countless army of dedicated volunteers and even, dare I say it, the government. Regrettably, this single book cannot hope to do justice to all the sites, for each and every one of them could fill several books on their own merit, such is the historical worth of each site. However, what we can sample is the breadth and depth of Britain’s archaeology. First of all, there are the big, well-maintained, signboard-filled sites, complete with their tours and guidebooks and occasional visitor centres. They range from the Tudor warship, the Mary Rose, sunk 500 years ago in the Solent off the south coast, to the ancient stone towers called brochs, which defended the rocky northern shores of Scotland. Other monuments of every kind from prehistory right through to the Second World War are less publicised but quietly stand guard on every shore and punctuate every region.

Then there are the archaeological sites that are famous, not for their visual impact in the landscape, but for their finds (now sheltering in museums). They may be ancient skeletal clues to our distant past, such as the scant 33,000-year-old remains of the ‘Red Lady’ of Paviland (now in the Natural History Museum in London). Or they may be finds-laden graves such as that of the Amesbury Archer (currently laid to rest with his grave goods in the Salisbury Museum) or even the rich Anglo-Saxon warrior bling of the Staffordshire Hoard (viewable in all its glory in the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent).

Some major sites have ongoing research programmes and excavations where active archaeology is still visibly continuing and regularly brings new information to light. The vast Neolithic ceremonial site at the Ness of Brodgar in Orkney and the Roman fort at Vindolanda, where the unique writing tablets were found, are just two magnificent examples where you can see present-day archaeology in action. Watching the past be unearthed, hearing about the way the finds surfaced and maybe even meeting some of the people involved in their unearthing is an inspiring and enriching experience.

Fig. 5. Ongoing excavations, like these at the Roman fort at Vindolanda, can be visited – and sometimes even taken part in. (© The Vindolanda Trust)

Some recent sites remain inaccessible to the general public for very good reasons: Neolithic giant pits found by scanning around Stonehenge’s Durrington Walls remain buried; Bronze Age Must Farm is in an active working quarry; and the unique Homeric mosaic in the Rutland Roman Villa that hit the news in 2022 was re-buried for its own safety on a working farm.

Other sites were excavated decades ago, but are now enjoying the status of established tourist attractions: Neolithic Skara Brae on Orkney, found in 1850 after a huge storm and high tides ripped the grass and soil away, is an obvious example. Many other sites, such as medieval castles like Beaumaris on Anglesey, and Roman sites such as Housesteads Fort on Hadrian’s Wall, are justified in attracting thousands of visitors a year. When visiting such places, it’s easy to be caught up in the throng and swept around at camera-snap speed, but it’s well worth pausing a while longer and taking a closer look. Traipsing around along the guidebook’s tour is one excellent option but another is more dynamic and rewarding: get up close and get familiar with the site. Notice the special interesting bits that stand out. And, as you visit more archaeological sites, regular features soon become familiar: the long barrows and round barrows of prehistoric ritual landscapes separate into distinct markers for different eras; the hypocausts that provided underfloor heating rapidly become an unmistakably Roman construction; and the first-floor entrance to medieval fort towers becomes a familiar set piece. Soon the features that represent particular eras, from Roman mosaic styles to rounded Norman or pointed Gothic church windows, all become clues to the age of the site.

UNRAVELLING THE PAST

Of course, it is crucial to realise that life isn’t always that easy. Different eras do not inhabit distinctly different areas and there are many multi-phased archaeological sites in Britain. You can’t often simply say ‘this is a Bronze Age landscape here, but over there on that hill is an Iron Age landscape and ne’er the twain shall meet’ because people simply do not, and did not, live like that: the Romans adapted the Neolithic henge of Maumbury Rings as an amphitheatre; Iron Age folk reused already ancient sites just as we continue to live in villages that were once medieval; and bits of the modern A5 roars along above the ancient Roman Watling Street. Indeed, the HS2 rail construction works thunder through multiple eras of archaeology at any one time. The key point here is that each generation uses the land and buildings or sites around them for their own purposes. Stonehenge serves as a dramatic example of this.

New theories regarding Stonehenge crop up with the regularity of dandelions on a lawn as new, advanced investigations unearth fresh evidence but, as far as we can tell, as early as around 8000 BC, there was an early Middle Stone Age (Mesolithic) timber structure near the present-day site of the monument. Then, in about 3500 BC, long barrows were built to house burials and a causewayed enclosure was constructed and a Greater and Lesser Cursus (ritual avenue monuments) were added by the end of the millennium.

Excavations and analysis tell us that Stonehenge’s history is mindblowingly complex, covering thousands of years. A bank and ditch containing a timber henge was added in the Neolithic Age. Then a horseshoe of the Preseli ‘bluestones’ was brought from Wales and set up at Stonehenge before being rearranged inside newly erected massive sarsen stones. An earthwork avenue was eventually added in the Bronze Age and round burial mounds sprouted all around it. It has taken decades of skilled digging and science to unravel Stonehenge’s story as we know it so far, and the discoveries just keep on coming. And yet, even in this most complicated of sites we only have to stand and look to see the distinct cursus, long barrows, causewayed enclosure, avenues and standing stones which are still visible today: these flagship markers of a New Stone Age (Neolithic) ‘ritual landscape’ enable an informed guess that this was a lively ritual site in the Neolithic, over 5,000 years ago. Meanwhile, the round burial mounds silently announce that it was still important 1,000 years later in the Bronze Age.

So, whether it’s large and famous like Stonehenge or just an anonymous mound in a field near you, archaeology often has distinct features that tell us how old it might be and to which age it probably belongs. But just where can we find those tell-tale links with the past?

SPOTTING HIDDEN ARCHAEOLOGY

In an age of expensive leisure activities and extortionate family days out, archaeology-spotting is a refreshingly cost-free hobby. It is true that some of the great and the good, like Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire and Orkney’s Maeshowe tomb, charge us to visit them, and rightly so, because you cannot maintain such sites without substantial funding. But many of our impressive sites are absolutely free to visit, being funded and cared for by national schemes. Prehistoric forts like Mam Tor sit on public hillsides and the 4,500-year-old triple stone circles of the Hurlers loom out of the landscape as you walk on bleak open spaces like Bodmin Moor. Many Roman ruins like Silchester’s town walls, deserted medieval villages like Wharram Percy, and stumps of castles which litter our countryside, also have free open access granted to them.

However, these are the official sites. There is another side to archaeology. There are countless archaeological features throughout Britain that are humble and, despite being remarkable, are often ignored. They have no guides and no signboard. They have survived, not because of a grant or sponsorship, but simply because they are out in the open countryside, where they have been left unnoticed and in peace, unsmothered by new buildings and prey only to the elements. There are thousands of these modest tumbledown ruins and grassy lumps and bumps which rarely get into any of the guidebooks. Every one of them is archaeology with its own tale to tell, and this modest archaeology beneath our feet peers at us from the unlikeliest of places. To get the best out of a walk through history, don’t just admire the view, get into the habit of looking closely for a number of tell-tale archaeology clues:

LOOK OUT FOR …

Crop marks – most obvious in dry summers and usually seen from the air or looking down from higher ground, these are made by crops growing higher over in-filled ditches and shorter over buried wall foundations. Is there a pattern to them: are they in a line (an old wall?) or are they square (an old building or fort?), or circular (a roundhouse or burial mound?)?

Walls – are there abrupt changes in style and materials, showing different build-dates, or blocked-in gateways where a track once passed through?

Fig. 6. Blocked gateways in walls hint at old trackways that once went this way. (© Gillian Hovell)

Fields – are any of them very different in shape to the others around them? Look on maps and from high ground: are they modern and square, like a patchwork quilt, or ancient and round or wriggly?

Ancient stubby vestiges of field walls marching across deserted high moorland may be prehistoric, and low bulky stony wall foundations around small fields may be medieval (colour plate 3).

Molehills and rabbit scratchings – check them for pottery, flint, charcoal flung out from beneath the soil …

Flat circular or rectangular platforms in lumpy fields – was there a building here on such man-made, shaped terraces?

Dark or light patches in ploughed soil – is there something like slag (iron-working refuse) scattered here?

Lost walls – look ahead and around you for lines of spaced, single trees or scrubby remnants of hedging running across an open field where a boundary once was.

Veteran trees – trees with really large gnarled trunks, especially coppiced ones with multiple trunks springing from the base, can be hundreds of years old.

Rocks – Look closely at any earth-fast boulders you pass: do any of them have carved markings on them?

Under your feet – if there’s something ‘odd’ or different to the natural soil on the path, stoop and even feel to take a closer look: it might be hard slag, crumbly charcoal, a worked sharp flint, friable burnt stones or a bit of broken pottery.

Take your time: an archaeological site can put up with, and indeed invites, any amount of standing and staring. Allow time to ‘get your eye in’ to a new site.

TOP TIP

When you’re out and about near buildings:

Look up

Is there a date inscribed above the door?Is the slope of the roof exceedingly steep? Such roofs are often old and may have been thatched originally.Are there changes in roof line? For example, is there an old steep roof with a newer gentler sloping extension added on?Is there a ‘scar’ where a now lost roof line once was?Do chimneys or windows have any noticeable styles? Do styles differ, indicating they were added at separate dates?

Look down

Are there older, wider foundation stones at the base of the thinner walls of a newer building?

Look around

Are there larger quoin (corner) stones in a vertical line in the middle of a wall? A wall with no large stones on the side of their ‘straight’ edge will be a newer extension.

The beauty of archaeology is that you can look out for it at anytime: from the car or train window; as you walk down a public footpath; or as you fly over it in a plane. All you need in order to visit sites more closely is some stout footwear and appropriate protection from the elements.

But better still, do a spot of homework before you go out: get a large-scale OS map and pore over it looking for italicised words like rems (remains), ruin, standing stone or fort. Take the OS leisure map for Dartmoor, for example, kit yourself out with a pair of stout boots, provisions and all-weather gear and you can tramp across an ancient landscape, from prehistoric stones to prehistoric settlements, soaking in the history as well as the rugged atmosphere and the beauty of the scenery.

Countless sites have been discovered on aerial photos. Indeed, Doonhill’s Anglian chief’s timber hall, south of Dunbar, was first spotted on aerial photos. You can ask to look at large crisply printed aerial photos (using a magnifying glass helps) at your local council Heritage Office but any aerial shot will do. Google Maps is a good internet source and has the advantage that you can ‘zoom in’. You may find strange patterns of crop marks in fields, the alternating line of old ridge and furrow ploughing, or unusual (and therefore probably old) field shapes.

All photographs, aerial or otherwise, are snapshots of a moment in the past: compare them with a modern OS map and you might see old tracks, boundaries that are now long gone, buildings and woodlands that aren’t there anymore. You may even notice the absence of modern roads. ‘Map regression’ is when you work backwards from modern maps to old maps and back further to even older maps. Then, keeping to public access or permitted areas only, get out there and see if you can spot those altered features on the ground.

To find out what local features are already recorded you can check the national archaeological databases of the National Monument Records (NMR) and local council Historic Environment Records (HER, aka Sites and Monuments Records). Many can be searched online through www.heritagegateway.org.uk. Check out local museums, too, and the Record Offices, and don’t forget the easily accessible books in libraries’ Local History sections.

History is all around us. It speaks to us in barely heard whispers but the past is separated from us by time alone. If we know where to look, we can find it.