19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

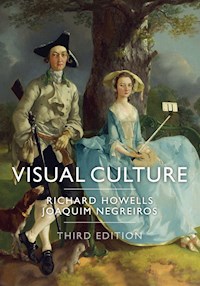

This is a book about how to read visual images: from fine art to photography, film, television and new media. It explores how meaning is communicated by the wide variety of texts that inhabit our increasingly visual world. But, rather than simply providing set meanings to individual images, Visual Culture teaches readers how to interpret visual texts with their own eyes. While the first part of the book takes readers through differing theoretical approaches to visual analysis, the second part shifts to a medium-based analysis, connected by an underlying theme about the complex relationship between visual culture and reality. Howells and Negreiros draw together seemingly diverse methodologies, while ultimately arguing for a polysemic approach to visual analysis. The third edition of this popular book contains over fifty illustrations, for the first time in colour. Included in the revised text is a new section on images of power, fear and seduction, a new segment on video games, as well as fresh material on taste and judgement. This timely edition also offers a glossary and suggestions for further reading. Written in a clear, lively and engaging style, Visual Culture continues to be an ideal introduction for students taking courses in visual culture and communications in a range of disciplines, including media and cultural studies, sociology, and art and design.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 937

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Front Matter

Preface to the Third Edition

Introduction

Notes

Part I: Theory

1 Iconology

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

2 Form

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

3 Art History

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

4 Ideology

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

5 Semiotics

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

6 Hermeneutics

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

Part II: Media

7 Fine Art

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

8 Photography

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

9 Film

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

10 Television

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

11 New Media

Key Debate

Further Study

Notes

Conclusion

Glossary

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Figure 1

President George W. Bush, ‘Mission Accomplished’ media conference, 2003

Chapter 1

Figure 2

John Constable, The Haywain, 1821

Figure 3

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Wedding Portrait, 1434

Figure 4

The Master of Flémalle, The Annunciation, circa 1428

Figure 5

The Beatles’ Abbey Road album cover, 1969

Chapter 2

Figure 6

Jackson Pollock, Number 32, 1950

Figure 7

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Milk Jug and Fruit, circa 1900

Figure 8

Mark Rothko, untitled, 1969

Figure 9

Rembrandt van Rijn, self-portrait, circa 1663

Chapter 3

Figure 10

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, circa 1480

Figure 11

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, circa 1502

Figure 12

Follower of Rembrandt, Man Wearing a Gilt Helmet, circa 1650–2

Figure 13

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937

Chapter 4

Figure 14

Thomas Gainsborough, Mr and Mrs Andrews, circa 1750

Figure 15

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533

Figure 16

Frans Hals, Regents of the Old Men’s Alms House, 1664

Figure 17

Frans Hals, Regentesses of the Old Men’s Alms House, 1664

Figure 18

Ellen Harvey, The Nudist Museum, 2010

Figure 19

François Boucher, L’Odalisque Brune, 1745

Figure 20

Gustave Courbet, The Origin of the World, 1866

Figure 21

Plan for Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon of 1791

Figure 22

Publicity image from the ISIS propaganda video Flames of War, 2014

Figure 23

Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, 2001

Chapter 5

Figure 24

Mitsubishi Pajero, Lisbon, 2010

Figure 25

Mercedes Benz logo

Figure 26

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) logo

Figure 27

Che Guevara mug

Figure 28

Still from Renault 19 car commercial (UK TV, 1994)

Chapter 6

Figure 29

Eric Cantona and a seagull

Figure 30

A cockfight in Bali

Chapter 7

Figure 31

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist, ci…

Figure 32

Simone Martini, The Road to Calvary, circa 1340

Figure 33

Child’s drawing of a cat

Figure 34

Demonstration of Alberti’s perspectival grid system

Figure 35

Perugino, The Giving of the Keys to St Peter, circa 1482

Figure 36

Han van Meegeren, Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus, 1937

Chapter 8

Figure 37

Alfred Stieglitz, The Steerage, 1907

Figure 38

Albert Southworth and Josiah Hawes, Early Operation Using Ether for Anesthesia, …

Figure 39

Peter Emerson and Thomas Goodhall, Rowing Home the School-Stuff, 1886

Figure 40

Aaron Siskind, San Luis Potosi 16, 1961

Figure 41

Cottage in the Dungeness nature reserve, England

Figure 42

The same cottage in Dungeness, photographed from the opposite direction

Figure 43

The same cottage pictured at night

Figure 44

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936

Chapter 9

Figure 45

The Lumière Brothers, La Sortie des Ouvriers de l’Usine (France, 1895)

Figure 46

The Hepworth Manufacturing Company, Rescued by Rover (UK, 1905)

Figure 47

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (UK, 1980)

Figure 48

Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (France/Italy, 1961)

Chapter 10

Figure 49

Detective Inspector Sally Johnson in The Bill (UK TV, 1984–2010)

Figure 50

The Huxtable family in The Cosby Show (US TV, 1984–92)

Chapter 11

Figure 51

Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, The Cottingley Fairies, 1917–20

Figure 52

Andy Goldsworthy, Snowballs in Summer, 2000

Figure 53

Still from Armageddon (USA, 1998)

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

ii

iii

iv

ix

x

xi

xii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

165

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

Dedication

For Philippa

Visual Culture

Third Edition

Richard Howells

Joaquim Negreiros

Polity

Copyright © Richard Howells and Joaquim Negreiros 2019

The right of Richard Howells and Joaquim Negreiros to be identified as Authors of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2003 by Polity PressThis third edition published in 2019 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press101 Station LandingSuite 300Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1881-4

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Howells, Richard, 1956- author. | Negreiros, Joaquim, author.Title: Visual culture / Richard Howells, Joaquim Negreiros.Description: Third edition. | Medford, MA : Polity, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references.Identifiers: LCCN 2018019536 (print) | LCCN 2018019909 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509518814 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509518777 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509518784 (paperback)Subjects: LCSH: Visual literacy. | Visual learning. | BISAC: ART / History / General.Classification: LCC LB1068 (ebook) | LCC LB1068.H69 2018 (print) | DDC 370.155--dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019536

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION: A NOTE FOR LECTURERS, TUTORS AND FACULTY

As Visual Culture enters its third edition as a book, the importance of visual culture as a discipline continues to increase. And while some things have changed, others remain the same. That’s what we have done with this third edition.

What remains the same is our dedication to increasing the visual literacy of the college and university students at whom this book is aimed. It is still a book about how meaning is communicated in visual culture. As before, we do not seek to provide set meanings to a limited number of particular images. Rather, Visual Culture guides readers to interpret any number of visual texts with their own eyes. We do this by providing them with a methodological toolbox that they can put into use for themselves.

The first part of the book remains structured around method; the second is still arranged around media. We continue to focus on what we hold to be the major conceptual issues, because in terms of visual theory and analysis, the central ideas remain relatively constant – even within a world of (seemingly) perpetual change. And of course, we remain committed to writing clearly. Rather than seeking to impress our fellow scholars with the depth and sophistication of our knowledge, our mission continues to be to explain sometimes complex concepts to new readers in the hope that not only will they understand us, they may also find the experience enjoyable.

Meanwhile, the visual world around us continues to change. We observe, for example, increasing numbers of formerly printed publications now being available only in electronic form. For example, in March 2016, the Independent became the first British national newspaper to move from print to a digital-only format. We think it will not be the last, especially as subscription-based, internet versions of serious titles such as the New York Times grow in popularity. Readers of our chapter 11 on ‘New Media’ will continue to question whether the changes in media at the same time involve changes to the message.

Traditional news media are being over-shadowed in other ways too, and the United States Presidential election of 2016 raised important issues beyond the merely party political. As the campaign between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton gathered steam, it became apparent that Internet news sources were becoming increasingly hyper-partisan and, in some cases, entirely false news stories were circulating which, it was argued, influenced the eventual outcome of the election. Let’s begin with an example: during the campaign the Denver Guardian reported that the Federal Bureau of Investigation director implicated in the leaking of details about Hillary Clinton’s emails had killed himself after murdering his wife. The story, which included a vivid photograph of a house fire, was widely shared via social media on Facebook. The story was, however, completely untrue. The Denver Guardian was a fake news website, masquerading as legitimate. They completely invented the story. And it turns out that the photograph, although of a real house fire, had been taken by a neighbour back in 2010 and originally posted on image-sharing site Flickr before being appropriated and completely misrepresented as something else by the Denver Guardian. Other fake news stories circulated during the election claimed that Pope Francis had endorsed Donald Trump and that Hillary Clinton had sold arms to the so-called Islamic State.

According to BuzzFeed News, the top 20 performing fake news stories about the US election of 2016 generated 8.7 million shares.1 This figure becomes all the more significant when we consider that the difference between the two sides in the US presidential election of 2016 was just 2.8 million votes out of a total of over 136 million votes cast. According to BuzzFeed, three big right-wing Facebook pages published ‘false or misleading information’ 38 per cent of the time during the period analyzed, and three large left-wing pages did so in nearly 20 per cent of posts. BuzzFeed further claimed that ‘the least accurate pages generated some of the highest numbers of shares, reactions, and comments on Facebook — far more than the three large mainstream political news pages analyzed for comparison’. BuzzFeed’s Craig Silverman concluded that ‘The best way to attract and grow an audience for political content on the world’s biggest social network is to eschew factual reporting and instead play to partisan biases using false or misleading information that simply tells people what they want to hear.’2

The recent proliferation of hyper-partisan sites and false news stories has led to what some people are now calling the ‘post-truth society’, described by Oxford Dictionaries (who made it their 2016 ‘word of the year’) as: ‘Relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.’3 Due to the significantly visual nature of both Internet and broadcast news today, we wonder to what extent images and presentation contribute to this increasingly complex relationship with truth? It seems to us, however, that in visual culture true and false need not be entirely binary categories. Our fifth chapter (semiotics), for example, draws important distinctions between denotation and connotation, while chapter eight (photography) argues that even a ‘documentary’ photograph’s relationship with reality can be similarly complex.

The rise of international terror has led to us writing a new section within chapter 4 (ideology) as part of this third edition. Here, we discuss how images of power, fear and seduction have become part of the terrorist arsenal in the twenty-first century, and consequently part of our own visual culture. We investigate a significant evolution from images distributed by the militant Islamist group al-Qaeda in 2005 to those circulated by ISIS (the so-called Islamic State) in more recent years. We note the increasingly ‘sophisticated’ use of Western-style techniques in support of a distinctly anti-Western movement. It all combines to underline the ever-increasing, global importance of the study of visual culture today.

On a lighter note, we have also added a new section on video games as part of our ‘New Media’ chapter for this third edition. As video games have become much more visually sophisticated, it struck us that they now needed to be taken more seriously within visual culture. On a more theoretical level, we have expanded our section on Immanuel Kant in our second chapter (form) and added an introduction to the work of another philosopher, David Hume. Both thinkers made early and important contributions to the debate about taste and judgement, especially regarding matters of beauty. Is everyone’s taste entirely personal? Or are there more objective, universal criteria for aesthetic judgement? And can there be any such thing as ‘good’ taste? We welcome the contributions of philosophers to the study of visual culture, and note that the questions raised by Kant and Hume in the eighteenth century remain just as relevant (and tantalising) today.

Of course, we have updated the book more broadly along the way, including the further study sections, the index, glossary and bibliography. Finally, we are delighted for the first time to print this third edition in colour. We are aware that monochrome rendition of works in colour has always been second best – especially in a book about visual culture. The world is, after all, in colour and always has been – whatever old newsreels may lead us to believe! The reason we used black and white in our previous editions was with the best of motives: to keep the price of the book down for student readers. But things have changed. Since our first edition in 2004, the relative cost of printing in colour has gradually come down, and with the welcome support of our publishers we are now able to take this important jump while still keeping this latest edition affordable for everyone.

We are grateful to those who have supported this book in the past and who continue to do so with the third edition. This includes, of course, John B. Thompson, Andrea Drugan, Ellen MacDonald-Kramer, Sarah Dobson, Elen Griffiths, and Mary Savigar at Polity Press. Sacha Golob and James Grant were generous with their thoughts and suggestions on the philosophy of aesthetics; Btihaj Ajana and Paolo Gerbaudo on video games.

Parts of this revised version were completed during Richard Howells’ Visiting Fellowship at Exeter College, University of Oxford, so our grateful thanks to the Rector and Fellows thereof. King’s College London have again provided welcome support from both the Dean and Faculty of Arts and Humanities together with the Department of Culture, Media and Creative Industries – whose students also continue to provide useful feedback and helpful suggestions.

We would like also to thank and commend the increasing number of museums and art galleries who have begun making images from their collections available to the public via public domain dedication and open content programmes. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles are shining examples here. We hope that increasing numbers of others will follow.

Finally, the authors thank their friends and families for indulging their continued fascination with the culture of the visual.

Richard Howells, London

Joaquim Negreiros, Lisbon

Notes

1.

Craig Silverman, Hyperpartisan Facebook Pages Are Publishing False And Misleading Information At An Alarming Rate in

Buzzfeed News

,

https://www.buzzfeed.com/craigsilverman/partisan-fb-pages-analysis?utm_term=.adR85AKKOn#.bjRXBqMMa1

accessed 26 November 2016

2.

Craig Silverman, Hyperpartisan Facebook Pages Are Publishing False And Misleading Information At An Alarming Rate in

Buzzfeed News

,

https://www.buzzfeed.com/craigsilverman/partisan-fb-pages-analysis?utm_term=.adR85AKKOn#.bjRXBqMMa1

accessed 26 November 2016

3.

See

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2016

, accessed 14 November 2017.

INTRODUCTION

We live in a visual world. We are surrounded by increasingly sophisticated visual images. But unless we are taught how to read them, we run the risk of remaining visually illiterate. This is something that none of us can afford in the modern world.

During our lives, we are usually taught how to read the printed word. We are shown how sentences are made up of grammatical units, how authors go on to use a whole cornucopia of grammatical devices to get their meaning across, and how meaning is both created and communicated at a remarkably sophisticated level. We learn how to read as well as write. Things are much less straightforward in the visual world. Often, we are left on our own when it comes to figuring out what a visual image means.

That is what this book is about. This is a book that explores how meaning is both made and transmitted in the visual world. It seeks not simple solutions – answers – to particular and individual images. Rather, it aims to show us ways of looking for ourselves so that we will be able to tackle any visual text – whether it is a drawing, a painting, a photograph, a film, an advertisement, a television programme or a new media text – and be able to start getting to grips with both what it means and how that meaning is communicated. We will discover, even, how some images give away far more in meaning than their authors ever consciously intended.

These comparisons between visual images and printed text are quite deliberate because we will discover how ‘visual texts’ can be ‘read’ with just the same rigour – and with just the same reward – as the printed word. We really can get to work on them – to wrestle with them, almost – to begin to discover both how and what they mean. And just as with the printed word, it is best if we begin with deliberate strategies for analysis if we want to get a text to unlock its secrets as revealingly as possible.

In the chapters that follow, we will make our way through some classic theories of visual analysis. The aim is to explain each one as clearly as possible, while at the same time showing its benefits and disadvantages. We will discover that some will be far more useful than others – but not all in the same way. By the end of the book, we should be able to select each method (or methods) as appropriate for the task in hand, just as we would choose the right tool from the box for a particular hands-on job. This book, therefore, aims to bring all the useful approaches together in one volume, unifying them under a broad overall strategy.

Do not be afraid of the word ‘theory’. Yes, it can sound dauntingly abstract at times, and in the hands of some writers can appear to have precious little to do with the actual, visual world around us. Good theory, however, is an awesome thing. Just like a skeleton key, it is remarkable both in itself and also (and equally) in what it can do for us: it opens up all manner of things. But unless we actually use it, it borders on the metaphysical and might as well not be used at all. That is why in this book we will always be looking at examples; combining the theory of method with the practice of looking. It also explains why this book is divided into two parts, concentrating first on particular theories and then on specific media. It is designed to introduce us not only to methods we can think about, but methods that we can also actually use.

Those of us who are already creatively involved in the visual arts, or are planning a professional career in the media or communications industries, will need little convincing of the need for visual literacy. Creatively, we need to be able to ‘read’ as well as ‘write’, to learn how others have communicated visually in order, in turn, to learn from them. Further, we need to know how others will read our work, be they consumers, clients or critics. We need to be practically accomplished in these skills in order to make a living from them.

Visual literacy, however, should not be limited to those with a creative or professional interest in visual culture. On the contrary, the need is much more widespread. So much of today’s culture is visual that we all need to be visually literate in order to function coherently in the contemporary world. Today, for example, more of us get our news, current affairs and information from television than from the newspapers. Television, it need hardly be said, is an essentially visual medium that communicates primarily though pictures. Think of recent world events and you probably think televisually: the open-topped limousines of the Kennedy motorcade in Dallas, the wide-eyed famine victims in Ethiopia, the bifurcating vapour trails of the exploding Challenger space shuttle, the funeral cortege of Diana, Princess of Wales, and the explosion of flame as a hijacked airliner slices into the World Trade Center.

Television is constructed around pictures. Television producers know this, and so do politicians. When they seek to persuade, they usually do so televisually. This was something that was first grasped in 1960 when American presidential campaigners first began properly to exploit the new medium. Some 100 million Americans watched a then novel series of debates between Richard M. Nixon and John F. Kennedy. Kennedy looked better on television; most viewers thought he had won the debates and there is no doubt that he won the election.

It may seem strange to us today that there was anything remarkable about this. That elections are fought on TV is something we nowadays take for granted. It is not just the formality of debates, or the increasingly expensive and slickly produced election broadcasts. Candidates (and their teams of media handlers) are also aware of the importance of prime-time, editorially covered photo opportunities which compete for space in the evening news. A well-organized visual not only gets selected for broadcast; it can also encapsulate just the message the media gurus wish to get across.

1. President George W. Bush, ‘Mission Accomplished’ media conference, 1 May 2003; courtesy of J. Scott Applewhite/Associated Press

Of course, it doesn’t always work. Democratic presidential candidate Michael S. Dukakis tried to toughen up his image by riding around in a tank for publicity pictures during the campaign of 1988. Unfortunately, voters thought he looked ridiculous in an overly large military helmet with straps flying like the floppy ears of a cartoon character. He lost. In Britain, Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock tried in 1983 to emulate the Kennedy style by strolling, casually, along the edge of the beach. Unfortunately, the television audience only saw him slip and stumble into the water. The image dogged him, and he never became prime minister. For better or worse, visual culture is very much a part of the democratic process.1

International conflict is similarly entwined with the visual world. Long before photography, it was usual for artists to paint battles – usually to the gratification of the winning side. Later, official war artists would sketch or paint on location, and then their work would be engraved for newspaper reproduction. With photojournalism, people began to see what war actually looked like for the first time. Particular images began to take on iconic significance. A group of US marines raising the flag over Iwo Jima, for example, remains one of the abiding images of the Second World War, while a (then) unknown girl running burned, scared and naked down a Vietnamese road speaks with equal eloquence of the conflict in Indochina. We can probably all ‘replay’ such images in our minds as we read this; images that somehow concentrate so many feelings about the conflicts they represent. It is a cliché, of course, that a picture is worth a thousand words, but the trouble with clichés is that they are so often true. One of the wonders of pictures, however, as we will see especially in chapter 2, is that they can often take over where words are not enough.

The Gulf War of 1991 broke new ground: not only were images available live to audiences around the world, but pictures were concurrently available from both sides of the conflict. Both parties were seeking international public approval not only for their causes but also for their pursuit of those causes. The Western allies, for example, showed footage of ‘precision bombing’ with a missile finding its target via an enemy chimney (again, many of us can ‘replay’ this footage in our heads), while the Iraqis responded with sequences of civilian casualties. It was a sequence played out again with the aerial attacks on Afghanistan, beginning in 2001.

The Kosovo crisis of 1999 was, similarly, a battle for international hearts and minds – in addition, of course, to being a painful military conflict for those directly involved. The propaganda battle was, again, fought visually. Yet, while the military authorities had exploited the advantages of waging war visually in the Gulf, in Kosovo they found themselves on the receiving end of a media and a public now used to images of conflict. British television journalist Peter Snow, sceptical of allied claims of Serbian atrocities, was therefore able to demand of an increasingly uncomfortable NATO spokesperson: ‘Where are the pictures? Show us the pictures!’ Visual culture, in other words, had reached such a phase that the word of a NATO official was no longer good enough for the British media. The media wanted proof; the media wanted pictures.2

The pictures that depict our world are not necessarily moving pictures, despite the pre-eminence of television, cinema and related media. Newspaper and magazine photographs remain important, and have a ‘fixity’ that gives them more staying power than a fleeting, moving image. Just as in television, however, the images are by no means secondary to the words. Newspaper editors know this: the lead picture will always be above the front-page fold so that it attracts our attention on the news-stand. One hardly needs to stress the importance of the cover photograph of a magazine, no matter how fashionable or weighty its content.

Visual images, however, are by no means limited to the news media. They surround us every day in advertising, on packaging, on banknotes and on CD covers. They all have something to say, whether they are as informal as family snapshots or as imposing as art gallery canvases.

Try to imagine a world without visual culture. It is impossible. If we doubt this, we should just try closing our eyes for half an hour, or (on the other hand) walking down the street making a mental note of every form of visual communication that we see. Imagine, next, the same brief walk without the visual images. Visual culture, then, is not limited to museums and cable television. It has a part to play in decisions as important as whom we elect to govern us, and as seemingly trivial as which cereal we will choose for breakfast. If we are unable to read visual culture, we are at the mercy of those who write it on our behalf.

Let us return, then, to the concept of visual literacy. If we are presented with a piece of printed text, we can easily begin to get to work on it. We can note its content, style and structure. We can spot the literary and rhetorical devices used to present us with an argument, to persuade us of the writer’s point of view. We read such texts critically. If it is a contract, we look for the small print. If it is a sales pitch, we look for the ‘weasel words’, such as ‘a chance to win’ or ‘savings of up to 50%’. We ask, quite rightly, what is really being offered. We look for what is left out as much as what is included. We ask who is the author of a particular text, and how that may influence what they are trying to say.

We may of course differ on the meaning of a text. Anyone who has read T. S. Eliot, Shakespeare or scripture will understand this. Our disagreements, however, will be based upon a searching and sophisticated analysis of the words, together with all manner of reference to and quotation from the texts themselves. This is something at which we are all pretty good, at which we have had instruction, and with which we still get a lot of practice. How many of us, however, can apply the same logic, rigour and analysis to visual as to ‘verbal’ text?

It is important to stress here that this does not mean we should abandon verbal or literary analysis in favour of the visual. Despite the pre-eminence of visual communication today, we still need words and we still need to know how to read them in both the narrowest and the widest sense. We can see also how many of today’s new media texts (more of which in the final chapter) combine the visual with the verbal in order to get multilayered messages across. We need, therefore, to take both seriously. But it is to the visual that we need to pay remedial attention.

This introduction began with a deliberately provocative claim about visual illiteracy. Surely, we may respond, we are all perfectly visually literate in our increasingly visual world. The point is that we are not. Certainly, we are practised and experienced viewers of contemporary visual texts, but so much of this experience is grounded in habit rather than analysis. We are all too often complacent and accept visual literacy as a passive rather than an active pursuit. We take too much for granted, and (consequently) leave too much unseen. Instead of simply ploughing on with the job of reading, then, we need much more actively to think about how we read, and whether we ought to be reading differently. Bringing some sort of structure and self-awareness to this process is a very good place to start.

The visual world is not only a modern world. In returning to visual literacy, we are in many ways rediscovering the skills that our cultural predecessors knew better. Five centuries ago, for example, Western Europeans would have been able instantly to recognize each other’s precise social standing from the ordered detail of their dress, and they would, at the same time, have been able to interpret religious painting with an acuity that would put contemporary students to shame. In North America, native tribes would have recognized each other from the significant minutiae of their art and ritual objects, each rich with meaning that today would be dismissed, by the uninitiated, as mere patterns or designs. We need to remember, always, that the printed word is, culturally, a very recent phenomenon. It is a crucially important one, of course, but it needs again to be emphasized that visual literacy has a long and substantial tradition which historically overshadows much more recent kinds of ‘reading’. As Gyorgy Kepes argued in Education of Vision back in 1965, ‘We have to get back to our roots … we have to re-educate our vision.’3

This book will begin with six chapters on strategies for the analysis of visual texts. They will show us, in other words, six different ways of looking. The first chapter will concentrate on looking at the content of a work of art. We will study the practice of iconology, using an intriguing fifteenth-century wedding portrait as our first example and, to show that iconology is not limited to the past, a famous Beatles CD cover.

For the second chapter, we will move on to a way of looking which concentrates on the form rather than the content of a visual text. We will take as our examples two challenging paintings by American abstract artists – artists whose troubled lives were eloquently reflected in their work.

If anyone thought that this book was going to be all about art history, they would be surprised to discover that the traditional history of art gets only one chapter here, and this third one is it. We will look at a passionate painting by Picasso and a controversial portrait by Rembrandt (but is it?) to help us explore both the usefulness and the limits of art history in reading a visual text.

In angry contrast to the art historical approach, more recent theorists have provoked traditionalists by interpreting treasured works of art ideologically, claiming that such texts reveal entrenched societal attitudes about class, race, gender and wealth. In chapter 4, we will begin by looking at one of the most controversial writers in this area, contrasting his views with those of a direct opponent. The battleground will be two famous paintings from the Dutch golden age. We will then extend the discussion by examining a gender-based approach to the study of film and finally a sociological model of the circumstances in which cultural texts are produced.

In the fifth chapter, we will unravel the seemingly complicated study of semiotics and show how this can provide an extremely useful way of looking at popular culture. We will see how this approach reveals both the intended and unintended messages of advertising.

Part I concludes with a call for an interpretive and multilayered approach to the discovery of meaning in visual texts. We will consider the extent to which we can ever really isolate ‘the’ meaning, and close this sixth chapter by asking provocative questions about the meaning of culture as a whole.

The second part of this book shifts the focus from general theories to the analysis of specific media forms. It is a section that is, however, underlined by a continuing theoretical question: what is the relationship of visual culture both to reality and to the wider culture that it purports to represent?

We begin Part II with a chapter that examines drawing, printmaking and painting. It wonders how we learn to draw and paint, and discusses how much of what we take to be ‘realistic’ is simply a matter of learned convention. It asks how much the traditional fine arts use artifice in pursuit of the illusion of reality. As a case study, we think back to the childish drawings of our youth.

Chapter 8 takes a close look at photography and wonders whether it is a ‘realistic’ medium which can also be described as an ‘art’ form. It ponders the role of subjectivity and authorship in photography, and asks whether the camera produces images that are as dispassionate and objective as at first they may appear. Dorothea Lange’s Great Depression photograph of a migrant mother provides a first-class example.

From photography we progress to film. In the ninth chapter we discover that film, just like literature, comprises a variety of codes, forms and narrative structures. Unlike its close relation the theatre, however, it is able to transcend both time and space. Using the example of Stanley Kubrick’s classic movie The Shining, we discover that cinema is much more than simply pictures that move.

Television, the subject of chapter 10, is a medium we all spend a great deal of time watching, but which also tells us a great deal about ourselves. We must learn, however, that television is not a direct, literal reflection of our daily lives. Family comedy The Cosby Show provides a telling example.

Our final chapter comes up to date with new media. Video, DVD, multimedia, CGI and a whole host of other computer and digital technologies have brought about changes that would have staggered the old masters of the Renaissance, with whom we begin this study. One wonders whatever they would have made of Facebook. We use examples of World Wide Web pages and an Aerosmith music video to illustrate the theory. But when it all comes down to it, how much has really changed? Do these new media demand new analytic strategies? Do they present new challenges to our assumptions about reality, representation and visual culture?

There is both a progression and a symmetry, then, about this book. We begin with the study of relatively simple, fixed and two-dimensional texts and progress to a discussion of complex, multimedia forms. We consider increasingly sophisticated analytical strategies as part of that progression. We conclude by standing at the edge of the increasingly expanding new media frontier and looking back at how much has changed and yet how much has remained constant in our visual world.

Along the way, we will be introduced to some classic writers and writings on visual analysis. The aim is to get back to basics; to engage with the seminal texts on particular approaches. We will see what these authorities – who are too often nowadays referred to only in passing – actually had to say. By starting at the beginning, we will concentrate on the fundamental arguments for particular approaches rather than overwhelm ourselves with later and more sophisticated developments of them. Groundings, after all, should begin on the ground.

Each chapter begins with a ‘text box’, which contains a concise overview of what the chapter is about and the information it contains. It is aimed to help you get your bearings before we jump into a detailed and sometimes narrative account of a developing theory or approach. At the end of each chapter, you will then find a Key Debates section, which builds upon the previous, explicatory material by asking somewhat more advanced questions – with much less scope for easy agreement. We close each chapter by suggesting further readings so that, primed with the basics, you can use what we have written as setting-off points to further study for yourself. The aim here is not to précis everything that has ever been said on visual analysis. Rather, it seeks to introduce some fundamental ways of thinking about the visual world.

If we live in a visual world, learning to be visually literate is not a luxury but a necessity. This book seeks simply to begin to open our eyes.

Notes

1.

For more on the importance of the study of media to the preservation of democracy, see Richard Howells, ‘Media, Education and Democracy’, in

The European Review

9/2 (2001): 159–68.

2.

For more on the relationship between war and the media, including news, censorship and propaganda, see Philip M. Taylor,

Munitions of the Mind: A History of Propaganda from the Ancient World to the Present Era

(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995); Philip M. Taylor,

War and the Media: Propaganda and Persuasion in the Gulf War

(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998); and Phillip Knightley,

The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-maker from the Crimea to Kosovo

(London: Prion, revised edn, 2000).

3.

Gyorgy Kepes, ‘Introduction’, in Gyorgy Kepes (ed.),

Education of Vision

, Vision and Value series (New York: George Braziller, 1965), p. ii.

PART ITHEORY

1ICONOLOGY

This chapter introduces an approach to the analysis of visual culture that concerns itself with the subject matter or content of visual texts. We will discover that we can do much of this for ourselves at a practical, commonsense level, provided we are sufficiently rational and organized in our strategy. Things become more complicated, however, when we discover that a great deal of the content of a work of art can be symbolic, often even while disguised to look like everyday objects. Sometimes, then, the meanings are ‘hidden’ from immediate view, especially when we look at a work produced hundreds or even thousands of years ago. To help us structure the analysis of these more challenging images, we will follow the system devised by the famous iconologist Erwin Panofsky. Along the way, we will look at examples ranging from Northern Renaissance paintings to a Beatles CD cover. This will help us not only to unlock the meaning of our particular, chosen texts; it will also help us consider the advantages and disadvantages of iconology as a whole in our quest to discover the meanings of visual culture.

When we look at a painting, the first – and certainly the easiest – thing we look at is usually its content. We look to see what it’s of or what it shows. It is a very good place to start, and we must never be afraid to begin (as Dylan Thomas put it in Under Milk Wood) at the beginning.

With simple paintings such as John Constable’s famous The Haywain of 1821, we can figure out very quickly what it is supposed to be (see figure 2). We look directly to the evidence of the text itself. It is a view of a landscape; a quiet rural scene on a summer’s day. The sun is shining and the trees are in full leaf. The quality of the light suggests midday or afternoon. There appears to be little in the way of wind, although the clouds suggest a chance of rain. It looks warm: the river is low, and the men in the middle of the picture are wearing shirtsleeves. The central feature of the work is a horse-driven cart, ridden through the river by the two shirtsleeved men. They seem to be fording the water, moving away from us towards the fields in the middle distance, observed by a small dog on the riverbank nearest to where we are standing. To the left of the scene is a small building which fronts on to the river. It is possibly a mill, but there is little sign of activity, apart from a wisp of smoke from the chimney. If we look carefully, we can see a woman outside washing something in the river. The building does not seem to be in the best state of repair. The cart is empty (apart from the men), so we suspect that it is on its way to collect something, possibly hay, from the fields on the far bank, where there are men working in the distance. Another cart is being loaded on the far side of the large field. Certainly, the driver of the central cart appears to be in no particular hurry. He is moving at walking pace, and there is no evidence of splashing around the wheels of the cart. He is seated, not standing. From the inclusion of a horse-drawn cart (instead of a tractor), from the rustic appearance of the mill, from the dress of the men and from the lack of telephone cables, electricity pylons, roads and bridges, we can deduce that this is a scene from nearly 200 years ago.

2. John Constable, The Haywain, 1821, oil on canvas; National Gallery, London

There are three things to be said here. First, what we have just done was not entirely difficult. It took no education in the history or theory of art to do it. It was all, really, just common sense. Second, we did what we did simply from the evidence presented to us by the text itself. We didn’t have to look up the life and times of the artist, or even find out what a ‘haywain’ is (it is actually a cart designed to carry hay) to understand the picture. We just looked for ourselves. It all made perfect sense in its own right.

This brings us to our third point: Constable’s Haywain is a relatively simple picture in which what we see is pretty well what we get. There are no flights of fancy here; it seems to reproduce a real scene just as we might have seen it ourselves had we stood on the same spot as the artist in 1821. It is a pleasant but relatively undemanding piece of work, which probably explains its popularity on calendars, greetings cards and chocolate boxes. It is not difficult to understand.

Looking at paintings such as this, then, need not require an art historical education. All it does require is a modicum of common sense, and a keen eye for observational detail. It is simple detective work based on readily apparent evidence.

So much for The Haywain. When we come to look at other paintings, though, we will find the same methodology very useful, especially if we apply the same sort of checklist or system to new or as yet unfamiliar works. It will help us take a disciplined, structured approach, which will guarantee at least some sort of result.

Imagine, then, that we are confronted with a ‘mystery painting’ about which we know nothing. There is no handy museum label and no gallery catalogue to help us. We need to get to work purely visually on the evidence presented by the ‘mystery text’ itself.

First, we can ask what kind of painting is it? Paintings are traditionally – and conveniently – sorted into genres or categories of work. A landscape, for example, is an outdoor scene whose main purpose is to depict what today we may describe as a physical environment. It may or may not have some people in it, but they usually only appear in supporting roles because it is the land and not the population that is the real point of interest. A landscape need not be an old-fashioned, rural scene, although modern, urban versions are often called ‘townscapes’ or ‘cityscapes’. Again, these may or may not have people in them, but the main focus is not the figures but, rather, the lie of the land. The same may be said of the landscape’s close relation, the ‘seascape’. There may be promontories, lighthouses or even the occasional ship, but the real point of a seascape is, of course, the sea.

A portrait, on the other hand, is a picture of a person. They may be shown full-length, half-length, head-and-shoulders or just the face. There may or may not be some sort of a background, and the ‘sitter’ (as the subject of a portrait is often called) might be holding some sort of a ‘prop’, such as a book or even a skull. The main focus remains the person shown or ‘portrayed’. Sometimes, there may be several people included at once (a ‘group portrait’), or the subject might be riding a horse (a ‘mounted portrait’). Occasionally, the portrait may be of an animal (such as a much-loved horse or cat), but these are more usually called ‘equestrian’ or simply ‘animal paintings’. If the subject (and we’re talking about humans again now) has no clothes on, we may call this a ‘nude portrait’; if the attention is on the body rather than the face or even the character, we may call this, simply, a ‘nude’.

The ‘still life’ is another easily recognized genre. This is a study of inanimate objects such as fruit, flowers or even household objects. The things depicted need not be remarkable in their own right, as still lives are often distinctly everyday in their subject matter. It is possible to speak of subdivisions within the still-life genre, such as ‘floral’ works (pictures of flowers) or even ‘game pieces’ (pictures of dead pheasants or hares). They all remain still lives, however.

Finally, and to help avoid confusion, it is worth also mentioning the so-called ‘genre painting’. A genre painting is a scene from everyday life. Often, the subject is domestic, but it can never be a remarkable or earth-shattering event if it is to remain a genre painting or piece. The genre painting is much less common than the landscape, portrait or still life, but it is worth mentioning here to pre-empt any confusion between a ‘genre of painting’ and a ‘genre painting’. The similarity of terms is not very helpful; hence the need for an explanation.

Of course, the similarity of terms is not the only problem in describing types or genres of painting. The terms themselves can often falsely suggest distinct and exclusive categories. When, for example, does a landscape become a seascape or a group portrait become a crowd scene? Might there not also be aspects (say) of still life in a genre painting? And what about the categories we haven’t even discussed, such as interiors or battle scenes? Categorizing a painting is not an exact science; nor is it a simple one. Broad classification into immediately recognizable genres is, however, a very useful place to start when beginning to describe a painting. If proof were needed, it is remarkable how many works can initially and simply be divided into these basic categories. Do remember, however, that they are best used to aid us rather than constrain us.

Second, when we tackle a painting for the first time, we can ask simply what is shown. If it is a portrait, for example, is the sitter male or female, young or old? We can approximate the age of someone in a portrait in much the same way we can someone sitting opposite us on a train: is their hair greying or balding? Is their face wrinkled, ‘laugh-lined’ or fresh? Is there any facial hair? Look at the hands as well as the neck. We can also make an educated guess as to their ethnic group – does the sitter appear Asian, Caucasian or African, for example? What is their expression: friendly, proud, sad, imposing? Look next at what they are wearing. Look, in detail. From their dress, what can we surmise about their lifestyle, job, social class? Again, just as we would with a stranger on a train (we’ve all done it!), look at every clue to see what it may visually reveal to us. It really is visual detective work, and the evidence is right in front of us. Now, we can look at any ‘props’ they are holding or carrying. What do they communicate: a profession, a hobby, a fashion statement? Look also at the background: how does this add to our growing knowledge of the sitter? Is it a castle or a field, a ballroom, a bar-room or a studio? It all helps the building up of the impression, simply using the evidence of what is shown.

The location of a scene depicted in a visual text can provide a third area for analysis. With a landscape, for example, we can use the geographical clues to help us place it with some degree of accuracy. We do not need to be a trans-Saharan explorer, for instance, to deduce that a desert scene is more likely to depict the North of Africa than the North of Scotland, or that cacti are more indicative of New Mexico than of Nova Scotia. In addition, therefore, to the physical geography of the depicted site, we can also look at its vegetation. Wildlife, if any is shown, can also provide useful clues (kangaroos, for example, could be a bit of a give-away), but buildings provide more everyday evidence, from the kraals of Southern Africa to the cottages of England; from the whitewashed villages of the Mediterranean to the high-rise downtowns of North America. Again, we cannot be sure of always being right, but any sort of evidence should never be discounted.

As we begin to assemble more knowledge and information, we should, fourth, be able to start an approximation of the age, period or even year that a painting depicts. Again, look at the clues. If it is a townscape, are the buildings of wood, stone or glass and concrete? What are the roads like, and are they used by horses or cars? If they are cars, what kind of cars? Look at the street lighting: is it gas or electric – or is there none at all? Are there any billboards or advertisements? If so, for what kind of products? And if there are people, what are they wearing – can we use their dress to add to the evidence on which we will base our date? Finally, always be sure to look for what is not shown as well as what is shown. Familiar objects may be more articulate via their absence. Are there power lines, phone booths or parking meters, for example? Is there even a Starbucks? The absence as well as the inclusion of seemingly trivial things such as these in a painting can both provide valuable evidence.

If we are very lucky, we may feel able to make an informed estimate of the year shown in a painting. The time of year is usually much easier, however, and this constitutes our fifth stage for ordered looking at the subject-matter of a painting. For those of us who live in a continental climate, the markedly changing seasons provide a welcome consolation for meteorological extremes. Every season has its own look, moods and changing activities, to say nothing of types of weather, kinds of wildlife and cycles of nature. Those of us who live in cities have a less educated eye for such things than those from the countryside. It may also be another of those areas of visual literacy at which our ancestors were more proficient than we. How many of us, now, can approximate the date of the last swallow or first cuckoo in our own part of the world? Can we guess, within just a few weeks’ accuracy, when the first crocus will appear, or the last day for harvesting wheat? The year-round supply of produce in the shops has dulled our sensitivity to things that were common knowledge a hundred years ago. But we don’t need to be a farmer to still know something of the cycle of deciduous trees, or the general pattern of ploughing, sowing and harvesting. Snow, even to the most isolated inhabitant of the urban jungle, still means winter. The clues are still there in the paintings, even if nowadays we have to work harder to read them.

Sixth, we can often tell the time of day from a painting. Light and dark – of course – are good indicators of night or day, and if a clock is shown in a townscape, don’t be afraid to use it. Most situations are rather more challenging, but they are not impossibly difficult. If it is an outdoor scene, look for the height of the sun (highest at midday) or the length of shadows (longer in the mornings and evenings). Look also at the quality of the light: daylight has a redder tinge at either end of the day as the sun slants though the earth’s atmosphere. There is something wonderfully clear and thin about early morning light, especially before heat haze or even smog have had time to build up. We may also be able to tell the time from simple human activity: are they commuting, lunching, working or dancing? If the streets are empty, why? Are people wearing shorts or tuxedos? Business suits or cocktail dresses? If we look out of the window now, we will see that there are all sorts of ways of telling the time rather than simply looking at a clock. Looking at a painting is, in many ways, just like looking through a window. The visual world is there to be read.

Finally, a painting may even depict a particular moment. It could be a dramatic moment such as when a group of Spanish soldiers face a Napoleonic firing squad, or it could be as gentle as a passing squall at sea. Painting has difficulty in suggesting the passage of time, so traditional works usually depict a specific instant. Don’t be afraid, therefore, to notice the weather in detail – as every Englander or New Englander knows, it is likely to change. Is a cloud, for example, passing overhead? Is there a sudden breeze or break in the storm? Look at the characters: is the bride, for instance, stepping out of or into the carriage? Has a horse just started a race or taken a fence? Imagine how the painting might have been if it had been ‘taken’ two seconds earlier? It might make precious little difference. Then again, it might make all the difference in the world.