Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

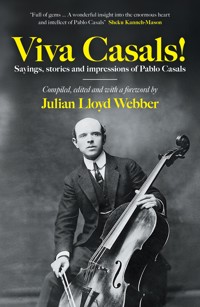

Not just a brilliant virtuoso player but a revolutionary force, Pablo Casals fundamentally redefined the art of playing the cello with his innovative approach and technique. Recognised in his own time as a performer without equal, his influence continues to touch musicians all over the world to this day. Yet Casals was also a man who resolutely stood up for fairness and peace, using his international fame to protest against injustice and fascism, earning him the respect of world leaders from the President of the United States to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. Celebrating the 150th anniversary of his birth, Viva Casals! draws on his own words and the recollections of others to bring to life his wit, wisdom, idealism and faith in humanity. Edited by Julian Lloyd Webber, one of the most creative musicians of his generation, this is a vivid portrait of a rare genius.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 108

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

iv

To all lovers of the cello throughout the world

v

vi

vii

‘I began the custom of concluding my concerts with the melody of an old Catalan carol, the “Song of the Birds”. It is a tale of the Nativity; how beautiful and tender is that tale, with its reverence for life and for man, the noblest expression of life! In the Catalan carol it is the eagles and the sparrows, the nightingales and the little wrens who sing a welcome to the infant, singing of him as a flower that will delight the earth with its sweet scent.’

Pablo Casals

viii

Contents

Foreword

by Julian Lloyd Webber

Every generation has its brilliant virtuosi – players who, by a common consent, stand that little bit apart from their contemporaries. And, just occasionally, another, greater, phenomenon appears: an artist so very special that he creates an entirely new horizon for his art, an entirely new approach to his instrument. Such an artist was Pablo Casals.

There is no cellist today who has not, in some way, been touched by Casals: his innovations wrought a revolution and changed for ever the accepted limitations of playing the cello; his teachings stand like a beacon, proud and resolute, for the rest of us to follow.

Such a magnificent upheaval was sure to cause disruption. When Casals first began to include complete xiiBach Suites in his programmes, other cellists were at first bewildered, then bothered, by his free interpretations. Yet Casals’s love and devotion to the cello were so overwhelming that even his stoutest critics were forced, in the end, to acknowledge the arrival of a player destined to change the course of music for ever.

I am trying to resist the temptation to comment on the ‘stories’ themselves, to single one or two out, even if some are, undoubtedly, more significant than others. But the account of Casals’s meeting with the theologist Albert Schweitzer indicates so clearly the cellist’s need to enter the political arena that I must allow one exception. During a conversation with Casals on the role of the artist as a public figure, Schweitzer observed: ‘It is better to create than to protest.’

‘Why not do both?’ asked Casals. ‘Why not create and protest – do both?’

Casals’s courageous stand against the fascists who had overrun his beloved Catalonia earned him the respect and attention of the world’s most renowned xiiileaders – from Presidents of the United States to the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

Here, then, is a portrait of Pablo Casals – in his own words and the words of others. Hopefully, no side of the argument has been left out. It’s all ‘in there’: the love of humanity, the wisdom, the idealism, the courage, the obstinacy, the inspiration and above all – shining through the pages like a rare and precious jewel – the overwhelming, triumphant and toweringgenius of Pablo Casals.

Full of wit, wisdom and faith in the innate goodness of mankind, VivaCasals!celebrates a great musician who transcended his art to become a world statesman. Revisiting these stories 150 years after Casals’s birth is inspiring, humbling and a timely reminder of the necessity to care in the face of inhumanity.

JulianLloydWebber

September2025xiv

Key life events

In concert

‘I only heard Casals once, but as long as I live I shall remember the sight of that homely, almost dumpy little figure – more like a village organist than an internationally renowned soloist; as long as I live I shall remember the atmosphere created around him, the uncanny hush as six thousand or more people in the Albert Hall seemed to hold their breath for the entire duration of the Bach Sarabande he played as an encore.’ – Antony Hopkins, writer and broadcaster

* * *

Ivor Newton, the renowned pianist, wrote: ‘He sits with his eyes closed and head slightly to one side (“as though,” an irreverent observer put it, “he didn’t like 2the smell of his cello”) in a state of almost exhausting concentration.’

* * *

‘Casals performs’, remarked one observer, ‘with an arrogant impersonality.’

* * *

After a particularly moving performance, Queen Elisabeth of Belgium was heard to ask: ‘Mr Casals, can you tell me, are we in heaven or still on earth?’

Softly he replied: ‘On an earth that is… harmonised.’

* * *

‘At one of my trio concerts with [Fritz] Kreisler and Casals,’ wrote the pianist Harold Bauer:

I noticed a man with a peculiarly inexpressive countenance sitting on my immediate left. He neither applauded nor gave the least sign of approval 3throughout the evening; I did notice, however, that his eyes wandered occasionally from Kreisler to Casals and then back to me. The programme ended with the Mendelssohn D minor Trio, where the coda begins with an impassioned lyrical outburst from the cello. My man took his hands from his knees, where they had rested the whole evening. He gently tapped his neighbour on the shoulder, and I heard him whisper hoarsely: ‘I suppose thatone will be Casals?’

* * *

Before a concert at his festival in Prades, Casals said to his duo partner, the Swiss-born pianist Alfred Cortot: ‘You’ve always chosen such perfect tempi. It’s as if you had a metronome set by Beethoven inside you. Young pianists today play much too fast. Do you realise that our total age is 163? Let’s go out there and teach them a lesson.’

* * *

An extraordinary incident involving a public rehearsal 4of Dvořák’s Concerto in Paris resulted in Casals being issued with a writ for breach of contract.

Scheduled to perform with the conductor Gabriel Pierné, he arrived at the hall to go through the work and was somewhat disconcerted to find Pierné apparently completely uninterested in their discussion. Suddenly the conductor threw the score on the floor, exclaiming: ‘This is a ghastly piece of music! It isn’t worth playing – it’s not music at all.’ Casals could hardly believe his ears, and he reminded Pierné that Brahms had also considered it a masterpiece. ‘Well, Brahms was another one,’ Pierné screamed, adding: ‘And you should be enough of a musician to know how awful the work is!’

The row grew more and more heated until word came to the dressing room that the audience was becoming angry at the delay. Casals insisted that he had no intention of performing the concerto with a conductor who felt like that about it – to do so would be a desecration. He not only would not but couldnot play it and was going on to the platform to tell the audience what had happened. But instead the dishevelled Pierné rushed on, shouting wildly: ‘Ladies 5and gentlemen – Pablo Casals refuses to play for you today!’

Bedlam ensued as the audience crowded on to the platform. A distraught Casals caught sight of Debussy standing in the wings and quickly tried to explain the situation. Surely hewould understand that no artist could perform under these circumstances?

To Casals’s astonishment, Debussy merely shrugged his shoulders and said: ‘Oh, if you really wanted to play, you could.’ Casals assured the composer he could not, packed up his things and strode from the hall.

The next day he received a court summons alleging breach of contract and, although the prosecution themselves acknowledged there was a discrepancy between the requirements of artistry and the requirements of law, the judge ruled against Casals, fining him 3,000 francs.

Over fifty years later, Casals said: ‘I would act the same way today. Either you believe in what you’re doing or you do not. Music is something to be approached with integrity, not something to be turned on or off like tap water.’6

* * *

The audience at a Casals recital in São Paulo remained blissfully unaware of the commotion which had been in progress only minutes before in the maestro’s hotel bedroom. Rehearsing feverishly, both Casals and his pianist, Harold Bauer, lost all track of time until they suddenly realised there was less than ten minutes to go before they were due on stage. Years later, Bauer still remembered their dilemma:

Off flew the day clothes and we pulled on our clean evening shirts in frantic haste. Black shoes: where were they? Collars, ties, studs, everything dashed into place with feverish speed. Into the box with Pablo’s cello, have I got all the music, yes, let’s be off. But Pablo still had his trousers to put on, and his trousers were rather tight. Setting his jaw and introducing his feet, he pulled violently. Cr-r-r-ack! The toe of his right shoe ripped right through the trouser leg, laying it open from the knee down.

There was no time even for consternation over this hideous mischance. Ring the bell, rush to the door 7and yell desperately: ‘Chambermaid! Chambermaid! Hurry here, for God’s sake! Come at once! Bring a needle and black thread! Hurry!’ The girl came flying, and in three minutes Pablo’s trouser leg was bound together again in a manner that would have done a sailmaker proud.

* * *

Cortot, reminiscing on his concerts with Casals and Jacques Thibaud, the French violinist, recalled what a great practical joker Thibaud was – usually at the expense of the other members of the trio:

One evening, in the artists’ room, Thibaud found a castor which had come off his armchair. Just as we were going on to the platform, he slipped it down Casals’s right-hand trouser pocket. Between the two trios Casals looked decidedly uncomfortable and, putting his hand into his pocket, pulled out the castor with a flourish.

Thibaud burst out laughing. Casals said nothing – but at our next concert I found it planted on me.8

* * *

Casals’s Viennese debut in 1910 began disastrously:

The Musikverein was packed – not a seat was vacant, but the first stroke I made with my bow went amiss and suddenly, with panic, I felt it slip from my fingers. I tried desperately to regain control of it, but my movement was too abrupt. The bow shot from my grasp and, as I watched in helpless horror, it sailed over the heads of the audience and landed several rows behind! There was not a sound in the hall. Someone retrieved the bow. It was handed with tender care from person to person still in utter silence. I followed its slow passage toward me with fascination and a strange thing happened; my nervousness completely vanished. When the bow reached me, I immediately began the concerto again and this time with absolute confidence. I think I have never played better than I did that night.

* * *

9