28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Here, Volkswagen enthusiast and prolific author Richard Copping examines, for the first time, the complete story of the T4 from the Transporter concept originated forty years before its presence at VW's Hanover factory, through its development period and full production life. Topics covered include: the background story 1949-1990; design concept to production in the 1980s; full analysis of the T4's specifications; face-lifted Caravelles and Multivans from 1996 onwards; petrol- and diesel-aspirated engines including the VR6, V6 and 2.5 litre TDI; the T4 story in the USA - the Euro Van and finally camping conversions. The complete story of the Volkswagen T4, produced between 1990 and 2003 and the first book in the English language to have been written, illustrated and published solely about the T4, beautifully illustrated with 300 colour photographs - a sparkling mixture of archive and modern-day imagery.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

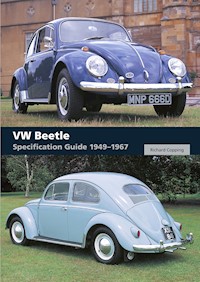

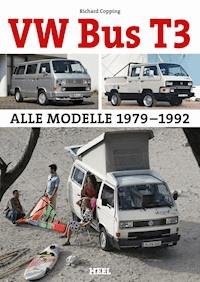

Ähnliche

Volkswagen T4

Transporter, Caravelle, Multivan,Camper and EuroVan 1990–2003

This e-book first published in 2013 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

© Richard Copping 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 647 5

Photographic Acknowledgements

The author and publisher would like to thank Rod Sleigh and Peter Edwards for help sourcing archive images. Photographs are from the author’s collection unless otherwise credited.

Images from Volkswagen T4 brochures reproduced by kind permission of Volkswagen.

contents

introduction and acknowledgements

1before the fourth-generation Transporter

2breaking the mould – the path to production

3a tale to be told – marketing the new model

4the specification and the models – launch period

5an evolving story – the early years

6production and chassis numbers, paint colours

7powering the T4 Transporter and Caravelle

8a new look for the later years

9T4 Camping – from Bilbo’s Design to Westfalia

10after the T4 – comparing the T4 with its successor

index

introduction and acknowledgements

Few would argue with the supposition that virtually all superseded vehicles suffer a nose dive in popularity, as well as a further acceleration in depreciation, when the new model first appears. While it would be wrong to suggest that one of the more desirable examples of Volkswagen’s fourth-generation Transporters or Caravelles, 1990–2003, will cost as much today as when it left the showroom, it is more than likely to attract a value considerably in excess of the products of rival manufacturers. First, there is the peripheral benefit derived from Volkswagen’s reputation for both the quality and longevity of its products. In addition to that, the T4 is undoubtedly helped by what can only be described as VW Camper mania, which has pushed the asking prices for the first- and second-generation models ever upwards. Indeed, the fanaticism is such that pristine early examples, 1949–1967, might well command parity with the very latest models. As a result of this phenomenon, the fourth-generation Transporter has never experienced a fall in its desirability and, unless the bubble of the VW Camper movement bursts, which seems unlikely, it probably never will.

Although the T4’s many, many fans have access to a number of magazines dealing with the subject and its successor, not to mention a variety of more general Volkswagen titles that include reference to it, as yet there has not been a book written in the English language dedicated solely to the fourth-generation models. As it was Volkswagen’s first front-engined, front-wheel-drive Transporter/Caravelle, or in reality the first in the mould of the new-look Volkswagen generated by the change from the air-cooled Beetle to the water-pumping Golf and its compatriots, there is undoubtedly a tale to be told. The story is even more interesting given that, to date, the T4 is the only generation to be offered, at least for the latter part of its production run, with different visual identities between the workaday Transporters and the people-carrying, quasi-MPV Caravelles. Add to this the fact that, although German purchasers might have been familiar with the weekender-type camper named the Multivan from the days of the third-generation Transporter, it was new to the British market during the lifetime of the T4 and the case for a book continues to develop. Similarly, the emergence of the Window Van as a workaday model with even greater flexibility than the Kombi of years gone by, and the curious state of affairs in the USA, with the T4 in its guise as the horrendously named EuroVan, demand explanation.

Lyndi and Joe Pester’s RHD Surf Blue Multivan on location in Austria. Photo: Lyndi Pester

Peter Edwards’ Techno Blue Pearl Effect Bilbo Celeste photographed in Cheshire.

So this book was commissioned and many thanks to Crowood for asking me to research the subject, compose the text, and collate the imagery, both of an archive nature and of the specially arranged photo-shoot type. Without the help of others the task would have been very much more difficult and the result nowhere near as satisfying to me.

In no particular order, I would like to thank a number of people. Peter Edwards gave me permission to photograph the pristine long-nose T4 that appears on the cover and elsewhere in the book. Peter also very kindly loaned me a wealth of information about Bilbo’s Design Campers that proved invaluable, as my own collection was sadly lacking.

Finding a straightforward ‘lived-in’ Transporter, preferably sign-written and finished in an attractive colour, was not as easy as I had anticipated. Fortunately, help was at hand only a few miles away. Many thanks to Dave Stewart for taking time away from his work so that designer and friend Steve Parkman could do something creative with what, to the owner at least, was merely trusty transport.

Grateful thanks to work colleague Lyndi Pester and her husband Joe who produced the delightful photo-shoot of their T4 Multivan in the suitably wintry but nevertheless picturesque setting of Austria. Lyndi and Joe had driven the vehicle from the borders of the English Lake District just in time for me to be thinking about one further model to feature in the book. The comparative rarity of a RHD Multivan only served to make their T4’s inclusion essential.

Next, I am particularly grateful to Rod Sleigh, long-term VW enthusiast and currently owner of VW Books, for a number of reasons. First, he kindly checked the more technical aspects of the text and in the process suggested several important additions, as well as providing supplementary information which has brought the book closer to the ideal of a T4 bible. Second, Rod provided access to his carefully collated records of chassis numbers, paint colours and more; and third, he also took the trouble to hand-deliver two full files of T4 brochures from his own collection for me to make use of as an invaluable supplement to my own horde.

That once-paltry catalogue of titles had been considerably enhanced when it was known that a T4 book was planned thanks to the dedicated trawling of the internet by my old friend Brian Screaton. Brian also volunteered to take my unread, unedited, and some might say barely literate, text and whisk it into a form that others would have a reasonable chance of enjoying, never mind reading with ease. An old hand at guiding me in the right direction, Brian richly deserves as usual my special thanks.

Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Saffron, who has not only attended numerous VW shows without complaint for as long as I have known her, but has also willingly accepted my absence from her side when a book is brewing.

Richard A. Copping

March 2013

Dave Stewart probably never thought his daily transport would make it into a book.

Volkswagen’s marketing department produced a wealth of celebratory material to mark the occasion of the Transporter’s fortieth anniversary in the year 2000. A series of publicity images portrayed all four generations, each in top-of-the-range passenger guise. Of the T4’s ancestors, prominence was given to the original version, which as a Micro Bus De Luxe was produced between 1952 and the summer of 1967. Photos: Volkswagen

1before the fourth-generation Transporter

Inevitably, any manufacturer, Volkswagen included, will endeavour to make as much as possible out of the launch of a new model. Increasingly specific and steadily more frequent pre-launch press releases, each full of carefully calculated hyperbole and a wealth of classy, striking images, will be issued free to journalists for editorial purposes. Then a centre-stage appearance at the most prestigious of the merry-go-round of motor shows will be arranged, and lavish test-drive schedules put in place for carefully selected individuals capable of spreading the positive word to a wide audience. All these are central to the advance generation of the very maximum of favourable publicity to aid the dealerships and their eager, smart-suited salesmen in selling the product.

The T4’s carefully manicured path to an official launch on 15 September 1990 proved no exception to the marketing rule book, at least in terms of the plans co-ordinated to give the latest Transporter the best possible start in life. However, while it was not exactly a damp squib, the new model lacked the cutting edge anticipated of its predecessors and so beloved of journalists. The reason was straightforward. The launch of the first-generation Transporter had announced a totally new concept to a market eager to embrace the latest technology. That of the second generation had offered a completely upgraded version of Volkswagen’s second best-selling model against what was perceived by critics to be an operation headed by an individual incapable of changing designs. Then, with the third generation a vehicle had been presented that defied the mood of the times through its retention of both an air-cooled engine and a location for that power unit at the rear of the vehicle.

In comparison to such momentous events, the new fourth-generation Transporter was almost blandly conventional. Its similarity with the offerings of other manufacturers was perhaps partly dictated by the now well-established, and almost taken for granted, new-look Volkswagen and its range of vehicles, which sported both water-cooled engines and a front-wheel-drive arrangement.

Ben Pon’s hastily scribbled sketch of his idea for a small commercial vehicle. Photo: Volkswagen

PON’S SKETCH

Many an official Volkswagen chronicler will advise the unwary enthusiast that the birth of the Transporter was a straightforward affair involving an opportunist Dutchman and a British army Major. The Pon family in Holland had chosen to quit as Opel Dealers following US giant General Motors’ acquisition of the German firm in the 1930s. There then followed a prolonged period when Ben Pon battled to acquire the Beetle as a new mainstay for the family business. Thwarted in his attempts in the Nazi era, when the Third Reich was crushed and consigned to a dark and dismal dungeon of history, and Germany was under the benign wing of the Control Commission for Germany, Pon set about his task once more with relish and soon captured the attention of the Senior Resident Officer at Wolfsburg, Yorkshireman Major Ivan Hirst.

On one of his not infrequent visits to Wolfsburg, Pon came across a mode of transport that had been endowed with the name Plattenwagen (literally ‘flat car’), a rudimentary vehicle designed by Hirst for the purpose of moving items from one part of the damaged factory to another following the army’s request to retrieve vehicles it had loaned to Wolfsburg for just such purposes. Pon immediately saw the potential in exporting this vehicle to Holland, but the idea was firmly thwarted by the Dutch Transport Authority – the Plattenwagen’s design, where the driver sat at the rear of the vehicle, flouted just about every rule in the infant health and safety book.

Still, the Plattenwagen had triggered a thought in the entrepreneurial Pon’s ever-fertile mind and, on his visit to Wolfsburg on 27 April 1947, he hastily scribbled the outline of a small commercial vehicle inspired by the ‘flat car’. The essence of his creation was a box-shaped structure designed to carry loads of up to 750kg. The driver and any accompanying passengers sat over the front wheels, while the engine was at the rear, carefully mounted above the axle and easily accessible via a large lid at the rear of the vehicle.

Historians employed by, or under the influence of, Volkswagen since the late 1960s proclaim Pon’s sketch as denoting the birth of the Transporter and anniversary celebrations relating to the date of the drawing are assiduously organized with an appropriate degree of razzamatazz. However, there is a fundamental flaw in the theory. Hirst took Pon’s delivery van idea to Colonel Charles Radclyffe, his superior officer based in Minden and the military government’s servant charged with responsibility for light engineering in the British occupation. Faced with falling production numbers for the Beetle, a car increasingly saddled with a dubious reputation for reliability due to a lack of quality in its components and build, and a factory that two years after the cessation of hostilities still lay more or less derelict, Radclyffe rejected the proposal. His main concern was that both additional manpower and extra resources would be required to bring it to fruition, when clearly Wolfsburg was already overstretched.

THE APPOINTMENT OF HEINZ NORDHOFF

Despite the perilous state of the Volkswagen factory, it was decided as part of a wider plan for Germany’s future that there were sufficient grounds to believe it could prosper in the right hands. Berlin lawyer Hermann Münch, who had been appointed to look after the factory as custodian in the absence of a legal owner, knew little or nothing about the business of making cars. Any ideas that Ivan Hirst might have had concerning a permanent position at Wolfsburg, something he would later dismiss as the fantasies of over-active minds, were overlooked. Long-term occupation of Germany was never a serious consideration. Wolfsburg needed an expert car maker either as deputy to Münch or, more realistically, to replace him. Colonel Radclyffe recognized the management skills of one Heinz Nordhoff, a former director with Opel and during the war Director General of the Opel-Werke in Brandenburg, which by that time was the largest truck-making plant in Europe. After thorough training in Detroit, Nordhoff was fully versed in both modern sales and production techniques. He was dynamic in pursuit of his goals and had an insatiable desire to fill his days with tasks; in truth, he was a workaholic.

Heinz Nordhoff, Volkswagen’s Director General, 1948--68. It was his drive and determination that ensured that by late 1949 the Beetle was no longer VW’s only product. Photo: Volkswagen

Nordhoff’s appointment as Director General heralded Volkswagen’s rapid climb to become the fourth-largest car manufacturer in the world and producer of a vehicle that sold in its millions under his custodianship. This has been a dominant theme of many a history of Volkswagen but far less well known is Nordhoff’s pivotal role in the birth and development of the Transporter.

LAUNCHING THE NEW MULTI-PURPOSE TRANSPORTER

On 12 November 1949, before an assembly of specially gathered motoring journalists, Director General Nordhoff announced the arrival of a second Volkswagen model to join the Beetle. By this time Nordhoff had already secured the Beetle’s future by adding a De Luxe or Export model to the basic saloon, while Ferdinand Porsche’s original idea of producing a soft-top version of the car had come to fruition in the form of a four-seater Cabriolet assembled by Karmann of Osnabrück and a two seater Coupé created by Wuppertal-based Hebmüller. Beetle production was destined to jump from the paltry 8,987 units produced in 1947 under the auspices of the British to 46,146 vehicles by the end of 1949. From then on, numbers would escalate year by year until the mid-1960s, at which point more than one million cars were produced in a 12-month period.

The new Volkswagen model, the work of Heinz Nordhoff and his development manager Alfred Haesner, was conceived in the latter months of 1948, well before financial stability was assured. As such, although the essence of the concept remained intact throughout, compromises had to be made. The most notable of these was an initial reliance on the Beetle’s backbone chassis, a decision that had disastrous consequences as the first prototype broke its back under the stress of the load placed on it for an initial test drive. Some would argue that the borrowing of the Beetle’s 25PS engine for the much larger Transporter was another sign of the lack of funds, which prevented the production of a more appropriate engine. Countering this, others note that it was not until the 1960s that the Transporter was endowed with a more powerful engine than the Beetle, that is to say, long after Wolfsburg’s vaults were filled with the spoils of the ever-increasing sales that had followed Volkswagen’s rapid and unrelenting expansion into the markets of over 100 countries worldwide.

Nordhoff’s lengthy speech to the press at the launch of the first-generation Transporter was a carefully crafted piece of oratory, deft in emphasizing the revolutionary nature of much of the information imparted, while encompassing all the subtleties required to ensure that the new product benefited from maximum exposure. His exposé of the Transporter started with the revelation that Volkswagen had not just launched into the project without considerable forethought; indeed, exhaustive market research amongst those with a potential interest in such a vehicle had been carried out:

Early Delivery Vans lacked both a rear window and bumper. Many were finished in Dove Blue, as per this example. The chrome rather than painted hubcaps are an extra-cost option. Photo: Volkswagen

We arrived at the conclusion that it was not the typical half-tonner on a car chassis that was required, but a 50 per cent bigger three-quarter-tonner with as large as possible a load space; an enclosed van which can be used in many different ways. A half-ton payload is the largest that can be accommodated on a medium-sized car chassis, even with stronger suspension and bigger tyres, and hence the 500kg payload of all vehicles of this type. The situation immediately becomes clear when you look at a schematic drawing of a typical example of this type of van on a car chassis. The load area lies completely over the rear axle, which carries practically the entire payload and therefore soon reaches its natural limit. It also causes a very undesirable distribution of axle load, with strong dependence on the distribution of the load, and therefore negative effects on the suspension.

Having summarized what was wrong with vehicles already on the road and confirmed the futility of Volkswagen trying to emulate such defective designs (as Ferdinand Porsche appears to have attempted in the Nazi area, with his box-shaped creations humped on to the back of a Beetle), Nordhoff was somewhat economical with the truth when it came to the next stage in the birth of the Volkswagen Transporter:

We didn’t begin from the basis of an existing chassis … but instead we started from the load area – actually much more obvious and original. This load area carries the driver’s seat at the front and at the rear both the engine and gearbox – that is the patent idea for our van, and that is how it is built …

The van comprises a main area of three square metres of floor space plus, over the engine, an additional square metre while volume amounts to 4.5 cubic metres in total. At the front there is a three-seat passenger and driver’s area with very easy access and an unbeatable view of the road. At the back in a lockable, spacious and incredibly easily accessible space, there is the engine, fuel tank, battery and spare wheel. In short, neither the load area nor the driver’s area is restricted by these items.

Nordhoff continued his description of the new vehicle by alluding to the Transporter as it had been hastily reformatted after the disastrous failure of the first prototype once under test. The setback had occurred on 5 April. The pressure Nordhoff must have placed on Haesner is evidenced by the fact that Nordhoff could present the finished product no more than seven months later!

All this is produced as a complete self-supporting steel superstructure, with a low and unobstructed loading area …

The key components of the ‘self-supporting’ structure were two sturdy longitudinal members supported by five cross-members, which might be described as outriggers, positioned under the load floor and between the front and rear axles. These linked to side sills of a box-shape section, to which the Transporter’s body was duly welded. Further, the steel floors of both the load area and the cab were welded to the cross-members. Volkswagen, under the direction of Nordhoff the truck expert and the technically adept but pressurized Haesner, had created a revolutionary vehicle of considerable torsional rigidity. In defiance of the practice of the time, Volkswagen was one of the pioneers of the monocoque structure, certainly as far as commercial vehicles went.

Next, Nordhoff devoted his energies to a wealth of additional information intended to emphasize the ground-breaking nature of the design:

This vehicle weighs 875kg in road-going condition and carries 850kg, thus representing a best-ever performance for a van of this size, with a weight to load ratio of 1:1. Fully loaded it has a top speed of more than 75km/h, a hill-climbing capability of 22 per cent, and fuel consumption of nine litres per 100km. Both its suspension and road-holding ability surpass anything so far achieved. It can also transport the most delicate load on the worst roads without incurring the slightest damage.

With this vehicle the load area lies exactly between the axles. The driver at the front and the engine at the rear match each other extremely well in terms of weight. The axle load is always equal, whether the vehicle is empty or laden. That allows for ‘spring-synchronization’ which is just not achievable if you have variable axle loadings. It also makes the best possible usage of the weight-bearing ability of the wheels, and the capacity of the brakes. As you will be aware, we are never afraid to turn away from what is normally accepted and think independently.

We didn’t choose the rear engine layout in this van because we felt morally obliged so to do. We would have unhesitatingly put the engine in the front if that had been the better solution. We are not tied to the general view of technology. The famous ‘cab over engine’ arrangement gives such terrible load distribution ratios in an empty van, that it was never an option. You can tell from the state of the roadside trees in the entire British Zone how the lorries of the British Army, which have been built according to this principle, handle when they are unladen.

The location of the Transporter’s engine might have made the vehicle more difficult to load, in comparison with those of a more conventional if outdated nature. This must have been of concern to Nordhoff, but he had his response carefully worked out; a solution to the problem that would stand Volkswagen in good stead through the lifetimes of all models preceding the ‘conventional’ T4:

With a standard van you are in the predicament that it has to have its loading doors at the rear; our quandary is that we cannot do this. However, if I weigh these two scenarios against each other, then I am glad to be in our shoes, because the loading and access from the side is natural and normal – who would think of getting into a limousine from the back? Our van doesn’t need any clear space behind when it parks to unload, and the next vehicle can be close behind it. With regard to the sill height of the loading area, this is close to the kerb height – it is incomparably easy to load and unload.

Despite the assertion that side doors were advantageous, loading long and cumbersome articles into the early Transporter was not the easiest of tasks as, before March 1955, there was absolutely no access from the rear of the vehicle. Until this date Transporters are known as ‘barn-door’ models, due to the exceptionally generous size of the engine lid. After what might be termed in today’s parlance the ‘face-lift’ of 1955, the size of the engine compartment and its attendant lid were reduced (although it was still generous), and a relatively small upward-opening hatch was added at the rear of the vehicle. This was enlarged for the 1964 model year, which began in August 1963. The second-generation Transporter also featured a somewhat small opening hatch over the engine compartment, while its successor of 1979, or 1980 model year, came much closer to convention, having a comparatively massive upward-lifting rear door. The disadvantage of this arrangement in a vehicle with an engine at the rear was a more restricted access to the power plant, a criticism that could be justifiably levelled at the third-generation Transporter.

Commercial artist Bernd Reuters was employed by Volkswagen to enhance the appearance of both the Beetle and the Transporter. For Reuters the image reproduced from a brochure issued in 1951 is somewhat conservative in its nature, but nevertheless highlights many aspects of Volkswagen’s design. Photo: Volkswagen

However, in the wider context of the range of uses that Nordhoff always envisaged for the Transporter, side doors could be regarded as a distinct advantage in certain circumstances. While theoretically straightforward, double outward-opening doors re-mained the norm from the launch of the first-generation Transporter during November 1949 to its replacement with a new model in the summer of 1967, with effect from April 1963 a single, sliding, side-loading door could be specified.

The debut of the second-generation Transporter effectively put paid to outward-opening side doors and by the time the T4 was introduced, they were little more than a distant memory.

After his clever presentation of the advantages of side doors, Nordhoff turned once more to available space, finding a most convoluted way to sell the story behind this point. The subject matter was important then and was destined to resurface as a discussion point when the T4 was launched, with critics of a front-wheel-drive and front-mounted engine arrangement pointing fingers at the new model’s predecessor and laying claims to a superior loading or seating space in the older model:

I would now like to point out one other aspect which will become more and more important with the increasing number of vehicles: i.e. the degree to which the road area available to traffic is used. Normal vans made in the traditional way have a ratio of load area to total vehicle area of about 0.3; with our new van we easily achieve 0.5, over 50 per cent more.

The reality of Nordhoff’s assertion that with his all-new Transporter ‘nothing … [had] been left to chance, and in no aspects … [had] we taken the easy route’, was undoubtedly a significant factor in what would become a near unbroken record of ever-increasing sales. Typical as an example of the no-stone-unturned philosophy was Nordhoff’s tale of fuel consumption and aerodynamics:

In its first form this vehicle used 11 litres of petrol per 100km in general use. That was far too high for us, as we are of the opinion that it is not the purchase cost, but the running costs that decide the success of a vehicle. This will become even clearer after the expected rise in the price of petrol. Therefore we have done something that is a first with a van. We went into a wind-tunnel with the vehicle with the result that, with only minor adjustments to the shape, we reduced the wind resistance factor to CW 0.4 and therefore the average fuel consumption to 9 litres per 100km.

Nordhoff’s closing paragraphs of his address, amended in their sequence here to aid progression of the story, not only serve to add weight to his declarations of thoroughness in the creation of Volkswagen’s second model, and the first without the guiding hand of Ferdinand Porsche, but also outline the versatile nature of the design and its adaptability to many uses. This was the final and most important factor in the concept’s survival over the decades that directly led to the introduction of the fourth-generation Transporter some 40 years later and, indeed, that model’s eventual replacement with a fifth generation. Nordhoff’s Transporter did not merely lead in the field; it stood apart as a new concept and one that it took others many years to emulate with any degree of success. Curiously, while both the first- and second-generation Transporter might be described as invincible, and the third at least on a par with the competition, the conventionality of the fourth meant that its place in the crowd could no longer be so easily determined – but that is a matter for debate elsewhere in the story.

Nordhoff’s landmark speech to the press concluded with a series of model-defining observations:

With our new van we have created a new vehicle the like of which has never been offered in Germany before. A vehicle which has only one aim: highest economy and highest utility value. A vehicle that didn’t have its origin in the heads of engineers but rather in the potential profits the end-users will be able to make out of it. A vehicle that we don’t just build to fill our capacity – that we can achieve for a long time with the Volkswagen Sedan – but in order to give the working economy a new and unique means to raise performance and profit.

Of course, the Volkswagen van is fitted with everything that should be in a good vehicle, with splinter-proof glass for all windows, driver area heating, windscreen defroster, double windscreen wipers, and all accessories.

Today we are only showing you a few of the countless permutations that make it more user friendly.

THE ‘COUNTLESS PERMUTATIONS’

Ben Pon may have believed that his fortune would be made by a single vehicle – a straightforward delivery van that Volkswagen would build and he would sell to a multitude of transport-starved businesses – but Heinz Nordhoff had completely different ideas. Following the success of the second prototype in rigorous reliability trials, the Director General ordered the building of further prototypes. Each was to be ready for mid-October 1949, in good time for the press launch of this new concept. Nordhoff expressly instructed that the line-up must include a pick-up, mini-bus, ambulance and a vehicle for the Bundespost to use. In other words, Nordhoff saw the immense value of a vehicle capable of carrying more passengers than the Beetle and other larger family cars; he also appreciated the versatility of a second workhorse option, a flatbed without the restrictions of an enclosed area for goods; and all the while he foresaw that the Transporter would form the base for a seemingly endless train of special-purpose vehicles, ranging from a mundane carrier of the mail to a range of vehicles adapted to the more detailed demands of the ambulance service and other specialized users.

In the end, timescales, among other considerations, made it impossible to present to the press or indeed dealers all that Nordhoff had envisaged. However, an example of the people carrier, the so-called VW Achtsitzer, or eight-seater, was on view at the press launch, as was the remarkable combination of van and passenger transport, the aptly named VW Kombi. The principle had been established and Nordhoff made it a priority to ensure a rolling programme of further launches.

Delivery Van

Limited numbers of the Delivery Van were trickled out to carefully selected friends of Volkswagen in February 1950, to be followed by a general launch at the Geneva Motor Show in March of the same year. Whether it was Nordhoff’s idea or not, a further innovation was destined to encourage additional sales in succeeding years, particularly as Volkswagen threw the full might of its publicity machine into broadcasting its willingness to supply Transporters in nothing more than the grey primer of their underclothes. The buyer of a Delivery Van, or indeed any other model in the expanding range, could have his vehicle finished in the house colours of his business and liveried accordingly by his own contractors. To illustrate the popularity of this choice the first Delivery Van officially sold, bearing the chassis number 000014 and destined for the 4711 Perfume Company, was finished in primer. Of the more than 8,000 Transporters produced in 1950, some 36 per cent came out of the factory in nothing more than undercoat. Within the home market the figure for Delivery Vans alone climbed dramatically to 84 per cent of the total of the 4,345 for German usage.

Kombi

The second variation of the Transporter by no more than a whisker was the VW Kombi, a revolutionary concept originally designed to meet the financial constraints on the pockets of many a German in the first decade after the Second World War, by offering a dual usage. Nordhoff reckoned that where business needs demanded a vehicle with a generous carrying capacity, many would not have been able to afford the additional expense of a car for weekend or leisure use.

Essentially, the Kombi was a Delivery Van with two sets of three side windows and two rows of bench seats that could be removed or replaced as required. The Kombi was most definitely a primitive affair – the ‘walls’ and ‘ceiling’ of the so-called passenger area lacked anything more than a cursory coat of paint, while removing the seats relied on the simple task of turning a handful of wing-nuts. One minor concession to ‘luxury’ came in the form of rubber matting in the load area, but that is pretty much where it ended. Nevertheless, the Kombi proved an instant hit, as the production figures over the years confirm. It also held the key to open the door to a further expansion of sales.

Dual-purpose Kombi illustrated in a brochure produced in 1953. Although it proved particularly popular, in passenger mode creature comforts were few and far between. Photo: Volkswagen

Camping Conversions

Although the VW Camper was not a part of the official line-up, the Kombi’s existence inspired individuals and companies, most notably Westfalia in Germany and slightly later Peter Pitt, J.P. White (trading as Devon), Moortown Motors (using the Autohomes brand) and others in Britain, to produce their own camping conversions. Most interestingly, Westfalia took the Kombi concept one stage further in camper form, producing what was known as a Camping Box. This involved one or more pieces of ‘furniture’ tailored to slot into the nooks and crannies of the Kombi at weekends, to be removed in an instant on a grey Monday morning at the start of the working week.

The camping movement took the best part of a decade to evolve into something significant, but from that point onwards a considerable number of Transporters were being produced for the conversion companies, who were busily producing campers for an eager public. At the extreme, such was the demand for Westfalia products in the United States (Volkswagen and Westfalia having developed what was a loose alliance into an official partnership, at least in that market), that Volkswagen of America had to enlist the help of domestic companies to supplement the supply. Modern-day wits disparagingly describe such conversions as Westfakias!

The era of the second-generation Transporter and Kombi saw further growth for both Volkswagen and the camper-conversion companies; Westfalia alone built 22,417 examples in 1971. Sadly, the bubble burst, or at least was seriously punctured in 1973 when turmoil in the Middle East and the resultant oil crises, linked to rampant inflation in the Western world, sent markets tumbling. A recovery in Camper numbers came relatively quickly, but never at the pace previously experienced. Whereas once upon a time either the Kombi or the subsequent Micro-bus had invariably formed the platform on which conversions were carried out, increasingly manufacturers now turned to the Delivery Van. They were apparently happy to take a large tin-opener to its blank panels, creating in the process windows that were obviously add-ons to the original specification.

Fast-forwarding once more with the story of the non-official VW model, towards the end of the production lifespan of the T4, the Daimler, Chrysler, Mercedes Benz group, having already acquired a 49 per cent stake in Westfalia, successfully absorbed the remaining 51 per cent. Volkswagen had little option but to take decisive action and sever the near 50-year-old link, particularly as previous prototypes of a new generation of Transporters had been quietly despatched to Westfalia for them to work on, so that at launch point all parties were ready to debut the latest story virtually concurrently. Clearly, Volkswagen could not hand over a prototype T5 to their deadliest of rivals. As a result, Wolfsburg finally took the plunge and produced the first official VW Camper within the confines of the Transporter factory at Hanover. It was given the name California, the same as the last of the Westfalia-built campers, in order to imply that Westfalia had all along been a mere agent, carrying out the motoring giant’s wishes.

Volkswagen’s photographers produced many lifestyle images of the Micro Bus. Cleverly, this one, which dates from 1951, confirms both passenger- and load-carrying capacity. Photo: Volkswagen

1951 Micro Bus wedding ‘car’. Photo: Volkswagen

Micro Bus

Returning to the early years and the Transporter’s evolution, hot on the heels of the VW Kombi came the VW Achtsitzer or Micro Bus, which made its official debut on 22 May 1950. Clearly not designed to haul packages and parcels from one destination to another, the Micro Bus’s specification was inevitably more upmarket than that of the Kombi, the most noticeable differences coming in the form of car-like appointments, which included a complete headlining and fully trimmed interior. The Kombi’s trademark bare metal had no place in this more luxurious model, while its removable furniture was banished in favour of more permanent fixings. Pleated upholstery panels, daintily piped at the edges, modesty boards and even a plethora of ashtrays, were all intended to convey comfort to a party of passengers. Externally, the Micro Bus could be specified with either executive-style two-tone paint, or a single-colour option exclusive to this model.

1953 Micro Bus on picnic duties. Photo: Volkswagen

Volkswagen’s marketing message for the Micro Bus encompassed the idea that ‘in reality’ it was ‘not a bus but an oversize passenger car accommodating eight persons’, with the added advantage of ‘inexpensive travelling’. Essentially, through the lifetime not only of the first-generation Transporter but also of its successor, the message remained the same. However, a rebranding exercise part way through the production run of the T3 renamed the passenger-carrying vehicles as ‘Caravelles’. Only the workhorse models officially continued to be bracketed under the collective heading of Transporter.

There was a gap of a little over a year before the next model in the line-up joined the ranks. In June 1951, the VW Kleinbus ‘Sonderausführung’, or ‘special model’ for the home market and ‘Micro Bus De Luxe’ for everywhere else, finally appeared. With a couple of notable exceptions, neither of which was compulsory, this model was a more luxurious version of the already high-specification Micro Bus. Nordhoff and his team had bided their time so that the launch coincided with a feeling of returning affluence in Germany and elsewhere, for here was a vehicle of almost limousine status, epitomized by imagery such as a chauffeur at the wheel ferrying passengers to a luxury hotel or to that contemporary symbol of affluent travel, the aeroplane. The Micro Bus De Luxe was noticeably more expensive than the Micro Bus and visually bordered on the ostentatious. Where once there had been paint externally, triple chrome and bright-work now dominated, from the prominent VW roundel on the front panel to inserts on the bumpers. An impressive trim line down both sides of the vehicle in turn curved its way along the ‘V’-shaped swage lines surrounding the VW badge. Instead of the two sets of three windows on either side of the Micro Bus and Kombi, there were four windows, while an additional curved ‘glass’, or more correctly Plexiglas window, was sited in each of the upper rear quarter panels.

The luxury of a glamorous lifestyle was emphasized by Volkswagen’s photographer in 1951, who depicted the open-air lifestyle associated with a fold-back canvas sunroof. Photo: Volkswagen

Post-March 1955 image of the cab area of the Micro Bus De Luxe. Luxury in its day, but forty years later T4 owners would have been horrified if such a specification had still been available. Photo: Volkswagen

Use of a ladder helped the 1950s photographer capture many of the attributes associated with the De Luxe specification. Photo: Volkswagen

Although it was possible to specify a Micro Bus De Luxe without all its attributes, in its complete form it featured a large fold-back sunroof and eight delicate skylights in two banks of four on either side of the roof. In addition, more expensive upholstery, carpet instead of rubber, and protective bars to avoid luggage damaging the surrounding glass above the engine compartment – all contributed to the make-up of the most opulent Transporter of them all.

As with the Micro Bus, the De Luxe survived the transition from first-generation model to second, although there were those who thought that in its new guise it was not sufficiently distinct from its lower-ranking stable-mates. In third-generation Transporter terms, the De Luxe moved from the designation Micro Bus L to Caravelle GL, and the later introduction of the Caravelle Carat (a very superior version, as the name might imply) further muddied the waters pertaining to model trim levels.

Ambulance

The next variation on the theme of Wolfsburg’s Transporter to appear was the VW Krankenwagen, or Ambulance, a niche market addition which emerged at the end of 1951. Its appearance fulfilled at least in part Nordhoff’s wish to offer variants of the Transporter appropriate for public service use. As might be anticipated, production and sales numbers were far less than those of any of the core models. Total Ambulance production amounted to 481 vehicles in 1952 and 358 the following year, compared with 9,353 Transporters overall, followed by further growth to 11,190 in 1953. The all-time best in the lifetime of the first-generation Transporter for the medical option was still fewer than 1,000 vehicles. Nevertheless, the Krankenwagen benefited from both brochures solely dedicated to it, as well as equal inclusion in literature encompassing all aspects of the Hanover factory’s output. Nordhoff may have wanted to demonstrate the versatility of the Transporter body and its potential for a multiplicity of uses, but including the Ambulance at the core of the range seems a rather extravagant way of doing it.

Once introduced as an integral part of the Transporter range, the Ambulance warranted its own marketing material. These drawings by the artist Preis were used on the back cover of a brochure dating from 1958. Photo: Volkswagen

Without becoming entangled in the minutiae of the Ambulance’s specification, it is worth noting that, as the Transporter lacked any form of rear hatch until 1955, largely due to the size of the engine compartment and its attendant lid, Volkswagen had to deploy a reasonable amount of money to the re-working of the rear of the Ambulance. Twisting stretchers through the side-opening doors would have proved somewhat inconvenient, so the size of the Ambulance’s engine compartment was reduced and a hatch-type rear opening created.

The Ambulance remained a recognized option throughout the era of the second-generation Transporter but tended no longer to be included in generic brochures devoted to the main complement of workhorse models. As the years passed, specialist converters appeared to gain dominance. Brochures outlining the specification of Ambulances in the era of both the T3 and T4, not to mention the T5, are plentiful and imagery from those produced in the era of the T4 are reproduced elsewhere in this book.

Artist Bernd Reuters drew the Pick-Up with its cab away from the focal point of the illustration for good reason. The main aim of the work was to show the vehicle’s drop-down sides for easy load access and secure under-floor storage for more valuable items. Photo: Volkswagen

The Pick-Up photographed approaching the camera, taken from a low angle so that the peaked front to the roof section, part of the March 1955 revamp, can be seen. The peaked front housed a new and more effective ventilation system. Photo: Volkswagen

Pick-Up

The final planned core model in Nordhoff’s Transporter line-up appeared on 25 August 1952. This was the Pritschenwagen or Pick-Up, and the delay in its introduction from the plans laid in 1949 was largely due to the costs involved in its creation. Apart from the need to produce an additional press to form the single-cab roof panel, considerable resourcefulness was required to relocate both the petrol tank and the spare wheel from the barn-door engine compartment. The former found a new home to the right of the gearbox and above the rear axle, while the formation of a special well within the cab accommodated the spare. The engineering involved for both modifications was, as can be imaged, reasonably costly. Finding a home for the air intake vents behind the cut-outs for the rear wheels was a stroke of ingenuity. It was a feature bettered only by the creation of a lockable, and therefore secure, storage area situated below the flatbed, behind the cab and in front of the rear-mounted engine. As for the cargo area itself, this was carefully designed to be low enough to make loading as easy as possible, while drop-down side- and tail-gates made moving heavier items easier and also ensured that goods did not slide off the platform, either to be lost for ever or to pose a danger to other traffic.

The basic Pick-Up was very popular from its inception and the range was extended in 1958 to include both wide load bed and wooden platform options. In November of that year, Volkswagen also added a double-cab version to the range. Nordhoff had not planned such a vehicle, but coachbuilder Karosserie Binz had been successfully hacking and adapting the single cab into a double version to good effect since the autumn of 1953; inevitably, the finish of their special vehicles lacked the finesse of Volkswagen’s own. Although he was receptive to coachbuilders adapting his work (providing a sufficient stock of vehicles was available), Nordhoff was also sufficiently ruthless to produce his own model at the expense of the coachbuilder’s time and efforts.

November 1958 saw the addition of the versatile Double Cab Pick-Up. Photo: Volkswagen

Both the Single and Double Cab Pick-Ups remained popular throughout the remaining years of first-generation production and, as such, were guaranteed a place in the range of models offered in both second- and third-generation guises. However, the Pick-Up, as Volkswagen and the world had known it, had no place in the T4 range. This was because a greater versatility of a chassis cab was now a viable option, in an arrangement that offered even greater flexibility with regard to possible usage.

The High-Roof Delivery Van (left) features an extra-cost option sliding loading door. Volkswagen thrived on adapting vehicles for special-purpose usage as evidenced particularly by the Transporter (right). Both vehicles were prototypes for use by the German Post Office. Photo: Volkswagen

High-Roof Delivery Van

A further extension to the core range came in the autumn of 1961, part way through Volkswagen’s model year. This was the High-Roof Delivery Van, so beloved of certain businesses, including those in the clothing trade. The all-steel increase in height, which ran the full length of the vehicle, allowed the latest in high fashion to be hung full length, avoiding any creasing or other damage to the garments.

Again, the High-Roof Delivery Van survived the transition from first to second, and second to third generation. Along the way, for reasons of weight and cost, the one-time all-metal construction of such models was superseded by the introduction of elements of fibreglass, which on the second-generation Transporter made the top of the vehicle look rather like an upturned bath! The High-Roof concept will be discussed further in T4 guise later in the book.

Special Models

Essentially, the Double Cab Pick-Up and the High-Roof Delivery Van hovered between the status of models in their own right and what started as Sonder Packung, or special packs, and by 1956/1957 had become Sonderausführungen, special models with their own designations. To outline all the vehicles produced with such official titles over three decades and more would provide enough material for a book on its own, but the following list at least offers a flavour of what had been available before the T4 was introduced and what Hanover’s engineers would be expected to provide as options with the new model. Of particular note is that just as many special models were based on the Pick-Up as were offered for the basic Delivery Van.

Cover of a brochure produced in 1957 to promote the Special Model (SO1), a mobile shop. Essentially a Delivery Van with large opening hatch on the opposite side to the side loading doors, the SO1 was created by Westfalia on Volkswagen’s behalf. Photo: Volkswagen

Special models were not necessarily made at Wolfsburg or, after 1956, at the Hanover factory. A percentage of the ever-increasing total were undoubtedly produced at a Volkswagen factory, but a greater proportion were the preserve of an expanding list of independent but approved coachbuilders. For example, Westfalia’s production mainly, but not exclusively, of Camper conversions, relied on Volkswagen models. After a relatively short space of time each was allocated a special model or SO number. Decades later many enthusiasts know those Campers by a combination of letters and numbers, such as SO23, SO42 and so on, without realizing the significance of the designation.