18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

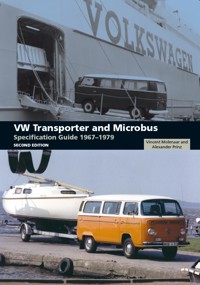

This comprehensive guide is the first one to tell the whole story of the Volkswagen Bay-Window Transporter, produced from 1967 - 1979. This new paperback edition deals with the Transporter's development, its technical evolution, the model codes, the specification detail changes, the factory fitted M-codes and Transporter export. Using this book, Bus enthusiasts can crack the codes of their own specific vehicle, to find out the factory-fitted specifications like paint and trim colours, engine and transmission types and even, the date of manufacture, model and destination code.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 247

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

VW Transporter and Microbus

Specification Guide 1967–1979

Vincent Molenaar and Alexander Prinz

Copyright

First published in 2005 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

Revised edition 2013

This e-book edition first published in 2014

© Alexander Prinz and Vincent Molenaar 2005 and 2013

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 545 4

Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of all material, the authors, and publisher cannot accept liability for loss resulting from error, misstatement, inaccuracy or omission contained herein. The authors welcome any correction or additional information.

Contents

preface

As a child I felt a great affinity with vehicles of all types, especially older ones. Finally, in 1999, I decided it was time to buy one for myself. I knew very little about them, but when I saw an old VW Bus for sale in a small town in Süd-Westfalen in Germany, I fell for its colour and its unique shape. I looked at the cutaway illustration of the T2a from the operating manual, which was displayed on the windscreen, and decided to take a test drive. It was very rusty, but the engine still ran well. It was a ’69 T2a Microbus with double sliding doors painted in Savanna Beige, and on a whim I decided to buy it. With this, the flames of my passion were inflamed.

I spent many hours restoring the Microbus, before moving on to my next project, in 2001 – a ’70 T2a Panelvan in relatively good condition, to which I returned the look of the first owner, ‘Klaus Esser KG’. The vehicle identification certificate of this Bus, which I got from the Volkswagen AutoMuseum, had some M- and Group- codes on it that even the specialists could not crack. There was no information available on the internet or in the VW Bus literature about the codes, except some basic information on the web page of the Dutch T2 enthusiast Vincent Molenaar. After doing some research on those mysterious codes in the VW archives and compiling some fascinating information about the Bay Window Bus, I felt that I had to put it all together in a comprehensive guide.

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Lothar Brune (thanks for your support), Rainer Esser, Hansjörg Fricke (HF), Alexander Gromow (AG) (thanks for your efforts), Harald Hohnholz (HH), Uwe Mergelsberg (UM), Kees Mieremet (KM), Karl Nachbar (KN), Christine Neefe, Aribert Kolms, Andreas Plogmaker (APS) (thanks for the great ‘last-minute’ pictures), Roland Röttges (RR), Volker Seitz, Axel Steiner, Michael Steinke (MS) (special thanks for proofreading the text), Wilhelm Thiele (WT), Eric Trinczek (ET), Olaf Weddern, Susanne Wiersch, Eckbert von Witzleben and Joachim Wölfer (JW). A number of companies/relief organizations provided amazing pictures: Arbeiter Samariter Bund (ASB), Avacon GmbH (A), Bahlsen GmbH & Co. KG (B), Bischoff & Hamel Zweigniederlassung der Automobil Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH (BH), Edeka Verlag GmbH (E), ExxonMobil Central Europe Holding GmbH (EM), Alfred Kärcher GmbH & Co. KG (AK), Kraft Foods Deutschland GmbH (K), Landespolizeidirektion Schleswig-Holstein (PSH), Malteser Hilfsdienst e.V. (MHD), Miele & Cie. GmbH & Co. (M), Niedersächsische Wach- und Schließgesellschaft Eggeling & Schorling KG (NW), Otto Versand GmbH & Co. KG, Polizei Braunschweig (PB), Polizeipräsidium München (PM), Pon’s Automobielhandel B.V. (P), Seba Dynatronic (SD), Archiv Björn Steiger Stiftung (BS), Stiftung AutoMuseum Volkswagen (SAV), Stiftung Rheinisch-Westfälisches Archiv zu Köln (R) and Vaillant GmbH (V). Volkswagen Nutzfahrzeuge helped in locating specific photographs and information about the T2. Pictures without proof of origin are from the author’s personal archive or were issued by the press department of Volkswagen Light Commercial Vehicles.

Special thanks go to my wife Simone.

Alexander Prinz, Hannover (Germany)

In the early 1990s I was an avid collector of Coca-Cola cans and I soon found that I needed a big car in order to visit swap meets around the country – empty cans take a lot of space. At about the same time, I was studying with Volkswagen-freak Jens Zeemans, who talked me out of buying a Trabant Stationwagen and into the purchase of a 1978 VW Kombi. Soon the Kombi replaced the hobby for which it had been bought in the first place. In October 1996 I bought a 1976 Bay Window Crew cab as a donor for the Kombi. While parting the car out, I stumbled across a small metal tag. Jens Zeemans told me it probably had something to do with optional extras, or ‘M-codes’. I could find little information about it on the internet, just a small list on the M-plate in the Split Window Bus. I joined the Type2.com mailing list and asked if anyone could help. Ron van Ness (USA) replied to my request and sent a list of M-codes he found on a microfiche – he even typed it all into the computer from the fiche reader screen!

Ron van Ness’s list was the beginning of my investigation. In 1997 I started an internet page about the Bay Window M-plate and its codes, which was soon moved to the server of Type2.com. It was at about this time that I got in touch with Erik Meltzer and Andreas Plogmaker (both from Germany). Erik supplied me with more M-codes and with Andreas I exchanged M-plate codes. Around the year 2000 Alexander Prinz contacted me in relation to my M-code site. He was able to gain even more M-code info via his job at Volkswagen.

Since I started the M-code web page in 1997, I have received lots of feedback and questions from Bay Window owners who want to know more about their Bus. Many people supplied me with additional info on their Bus, which gave me a good basis for research. It has given the data written in this book an extra dimension of reliability; not only did we look at what the original VW documentation told us, but we also related it to the Buses that are out there. As a result, detailed info could be added on model years, export markets and so on. After a few years of email-correspondence, Alexander came up with the idea of writing a book together. At almost the same time David Eccles contacted me to ask if I was interested in doing the sequel of his VW Transporter and Microbus: Specification Guide 1950–1967.

Many thanks go to: the people of Type2.com for kindly hosting my M-plate pages; all the Bay Window owners who sent me the M-plates of their Buses and those whom I bothered at meetings with my M-plate questions; and the members of the Type2.com mailing list for answering many of my questions during the years.

Also many thanks go to the three major M-plate providers over the years: Willy Seegers, Sjef van Ginneken and Peter Witkamp. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jens Zeemans, David Eccles, Robert Markus of the Politiemuseum Apeldoorn, Klaas Niemeijer (KLN), Tom van Wissen (TvW), Gjalt Erkelens (GE), Peter and Mary Royall, and Pon’s Automobielhandel B.V.

Should you have any remarks about this book, or questions relating to it, please feel free to contact us via e-mail at: [email protected].

Vincent Molenaar, Groningen (The Netherlands)

1962: One millionth VW Transporter leaving the factory.

1

worldwide success

A NEW IDEA AND A NEW FACTORY

Pon’s Inspiration

It was the Dutch Volkswagen importer Ben Pon who laid the foundation for the success story of the VW Transporter. In 1947, two years after the end of the Second World War, Pon tried to get a licence from the British military authority to export cars from the British-occupied zone of Germany to the Netherlands. The head of this authority happened to be Major Hirst, then manager of the Volkswagenwerk. The only model produced by the company in Wolfsburg at this time was the VW Beetle. After meeting Major Hirst at his residence at the British military authority in Minden (Westfalen), Pon went to visit the Volkswagenwerk in Wolfsburg. He made an important discovery there: the so-called ‘Plattenwagen’, developed in 1946 for transportation purposes on the company’s premises. These motorized trolleys were based on a Beetle chassis, with an extended loading area and a simple open cabin for the driver in the back, positioned over its engine.

VW Plattenwagen.

Ben Pon was intrigued by the simple concept, and immediately saw that there might be a need for such a transportation vehicle in the Netherlands. However, the Dutch Road Authorities would not allow him to import it as it was; an open, unprotected cabin cab at the back of the vehicle seemed to be rather dangerous in a vehicle destined for regular traffic conditions.

However, Pon was not prepared to give up easily on his idea. On 23 April 1947, he sketched in his notebook a simple outline for a commercial transport vehicle with a van body. It had a driver’s seat positioned in the front, the engine over the rear axle and an approximate distance between front and rear tyres of 2m. The gross weight was, assuming a similar weight distribution, 750kg per axle.

In January 1948 the Volkswagenwerk was handed over to the newly founded Federal Republic of Germany, under new general director Heinz Heinrich Nordhoff, a former engineer of Opel (General Motors). Ben Pon arranged a meeting with Nordhoff and showed him his ideas for the construction of a VW Transporter, which would be the second variant on the Beetle. Intrigued by the idea, Nordhoff instructed his head designer, engineer Dr Alfred Haesner, to start immediately on the new project. The project was given the number EA 7 (‘EA’ representing Entwicklungsauftrag, the German for ‘development instruction’).

1947: sketch by Ben Pon.

The so-called ‘Type 29’ (the internal Volkswagenwerk name for the new VW Transporter) took shape during 1949, with the first prototypes being built on the Beetle chassis. Unfortunately, though, early tests showed that a commercially used van, built up on a separate chassis, did not work. All prototypes had to be changed into a self-supporting body shell, supported by two frame side rails. The initial engine and axles of the Beetle were used. The engine had a displacement of 1131cc and a power of 23bhp (3,300rpm). The payload of the Type 29 was about 750kg.

In November 1949, Nordhoff was able to make a very successful presentation of four VW Transporters to the press. As a result of their favourable reception, more Type 29 Transporters were released in February 1950. Mass production started on 8 March 1950 with ten vehicles per day. The only thing missing was a real name for the new Volkswagen Transporter, all suggestions having been rejected by the patent office. Even without a ‘real’ name, however, the vehicle turned out to be the forerunner of all modern cargo or passenger vans.

Eventually, the works names ‘Type 29’ and, later, ‘Type 2’ or ‘VW Transporter’, all stayed in use. The Buses of the second generation were also called ‘Bay Window Buses’, but right up until today the Bus is more commonly referred to as the ‘VW Bus’, or, more affectionately, ‘Bulli’.

A Move to Hannover

The maximum capacity of the production in Wolfsburg was eighty VW Transporters per day. This was not enough to satisfy the enormous demand that resulted from the economic boom following the Second World War in Germany and other European countries.

1949: the first VW Transporter

Nordhoff decided to build a factory solely for commercial vehicles and began to look around for the ideal location. The new factory would need good motorway connections, and to be close to a port and to the existing factory in Wolfsburg, and the Volkswagenwerk management quickly settled on Hannover. On 1 March 1955, Heinrich Nordhoff laid the first foundation stone and the first VW Transporter left the new factory just over a year later, on 8 March 1956. Mass production began on 20 April of the same year.

1956: The new Hannover factory.

There was also a significant demand for engines within Volkswagenwerk, so Nordhoff decided to produce them in Hannover too. Engine production began on 11 November 1958, alongside the Transporter’s continuing boom all over the world. In 1962, just twelve years after its introduction, the millionth T1 left the Hannover factory.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE T2

As the VW Transporter of the first generation began to look a little dated, Volkswagenwerk thought about a successor to the T1. The first prototype to follow, in 1960, was called ‘EA 141’. For various reasons, Heinrich Nordhoff decided to discontinue any further development at the time, but three years later the project had a new beginning. The board of VW charged Gustav Mayer, head of the development department for light commercial vehicles at the time, to lead a thorough reworking of the T1.

The development of the second-generation Transporter took barely three years, with the green light being given around the end of 1964/beginning of 1965. With the help of testing engineers from former German car manufacturer Borgward (Bremen), and design engineers borrowed from Porsche, Mayer set about the difficult task of designing and developing a new generation of the Bus within a relatively short time frame. As time pressed on, the tests were made on an intensified testing ground by the time-lapse method; in this kind of testing, each driven kilometre represents 5km under ‘normal’ conditions.

During the development of the vehicle, the VW designers had to solve many problems, both small and significant. The body of the new-generation Transporter failed to last through the test cycle and had to be entirely reworked. The solution was a self-supporting body, consisting of an extra inner skin of metal sheet. This double-walled construction solved the strength problems, and allowedeven the braces between every window at both sides of the Bus, taken from the T1, to be removed. This resulted in larger side windows. Test drives with the optimized prototypes were continued and the team come closer to the completion of the new T2.

In order to test the durability of the vehicle under extreme climatic conditions, the Transporter was transferred to the north of Sweden for the so-called ‘winter try out’. The tests for heat resistance were done in South Africa. Both took place in 1966.

The new VW T2.

Even after volume production began, in the summer of 1967, the team continued to develop and improve the T2. In 1969, five Bay Window Buses with a fully galvanized body shell were completed for testing purposes. However, the costs for serial production of these Buses was too high, and mass production was not carried out.

A YEAR OF CHANGES

On 12 April 1968, the general director of Volkswagenwerk Heinz Heinrich Nordhoff died after a long illness. Largely due to his efforts, Volkswagenwerk AG had become a car manufacturer with an international reputation. He was succeeded as general director by Kurt Lotz.

Funeral march through the VW factory.

There was much sadness among the Volkswagenwerk employees at the loss of Nordhoff. His funeral took place on 15 May 1968 in the ‘Volkswagen-Town’ Wolfsburg. So that an enormous crowd of people could pay their respects, the coffin was carried through the streets of Wolfsburg and to the factory on the back of a black T2a Pick-Up without a cabin roof.

T2 Pick-Up carrying Nordhoff’s coffin.

First Model Change

Volkswagenwerk AG was still young, but it was about to initiate its first model change. Looking towards the beginning of the model year 1968, production of the second-generation VW Transporter began (in the summer of 1967) in the Hannover factory.

The Kombi, Microbus, Microbus L, Panelvan, and single- and double-cab Pick-Up were available right from the beginning of production. In the August 1967 brochure, which first introduced the Bay Window to the public, the Microbus was referred to as the ‘Clipper’ and the Deluxe version ‘Clipper L’. In the end, Volkswagen was not allowed to use the name since it was registered for a type of aircraft by Pan Am airline. Instead, Volkswagen had to use less inspirational names such as VW-Kleinbus or VW-Personen-transporter. However, the name ‘Clipper’ is still used by many Bus enthusiasts for the T2a Microbus.

T2: first Transporters leaving the factory.

Many innovations and improvements were made to the new Volkswagen Transporter compared with the Split Window Bus. For a start, it grew in length by 160mm to 4,420mm, with the result that the volume of the load compartment increased from 4.8 cubic metres to 5 cubic metres. The construction of the body was also changed. The evolution from the T1 into the new generation involved, among other developments, the introduction of a double-jointed rear axle, replacing the swing axle of the T1. Another innovation was the use of double-walled metal sheets on the car body to improve the body’s stiffness.

All Buses of the second generation received a large one-piece wrap-around windscreen, replacing the twin windscreens of the T1 and inspiring the nickname ‘Bay Window’. In addition, optional winding windows in the cabin doors and larger side windows were available.

A more powerful engine, with 47bhp at 4,000rpm, was introduced. The displacement performance was enlarged, from 1493 to 1570cc. The cooling of the engine was guaranteed by air-intake louvres on each side in the back of the Bus, behind the rear side windows.

The load compartment and the cabin were also rearranged. The T2 was equipped with a completely redesigned dashboard with padded edges and three separate instruments: fuel tank capacity display, speedometer and clock (optional extra). Furthermore, there were plastic control knobs marked with symbols, two external mirrors, a new ventilation system with ventilation grilles under the windscreen and adjustable fresh air vents inside, a safety-type ashtray, a grab handle for passengers, an adjustable front seat and a new handbrake lever under the dashboard.

The sliding door, an optional extra on the T1, was now fitted as standard. Also standard, from April 1968 for the special ‘Clipper’ model, was the metal sun-roof, which now made a decent modern successor of the well-known folding sun-roof of the Split Window Deluxe ‘Samba’ model.

Already familiar in the shipbuilding industry, fibreglass was introduced at Volkswagen for the roof of the T2 high-roof Panelvan. Compared to the preceding model, a huge reduction of weight could be realized by introducing this new and non-rusting material. The high-roof tops were manufactured exclusively by a French manufacturer for Volkswagen.

During this time, Volkswagen was also pursuing the idea of using similar parts; for example, the ashtray of the Bay Window Bus belonged to the Type 3 and the headlamps to the Beetle.

Expanding Capacity

The success of the second-generation Bus was overwhelming and in 1968 the two-millionth VW Transporter left the Hannover factory. It was a Titian Red-coloured T2a Clipper with a Cloud White roof, donated to the German charity project ‘Aktion Sorgenkind’.

The Hannover factory was unable to satisfy the enormous demand from the US market on its own, so Volkswagen decided to give some of the assembly work to the factory in Emden, a harbour city located in the very north-west of Germany. Production began in December 1967. Models for the US market that involved a high expenditure of work, such as Kombis, Microbuses and Microbuses L, were assembled there. The advantages were obvious: the US market could be served very quickly by the nearby seaport and the final assembly line in Hannover – formerly a bottleneck – was unburdened. The standard models, such as the Panelvan, Pick-Up and double-cab Pick-Up, continued to be produced in Hannover.

T2: the new driver’s place.

The success of the second generation lead to the highest-ever export rate of Transporters, even compared with today. In 1970, 72,515 Bay Window Buses were exported to the US market alone and the three-millionth VW Transporter left the production line on 3 September 1971. In the year 1972, a record 294,932 Bay Windows were produced worldwide including CKD.

1968: 2 million VW Transporters.

In April 1973 VW stopped production at Emden. One of the reasons for this move was the first oil crisis in the same year and the subsequent economic recession in Germany. All capacities were removed to Hannover, where, in 1973, 234,788 VW Transporters were built.

‘Basic-Transporter’ for developing countries.

In 1973 VW introduced the ‘Basic Transporter’, a very simple and cheap commercially used vehicle specifically designed for developing countries. This odd-looking vehicle, constructed from different parts and the 1600cc engine from the Volkswagen programme, disposed of a front drive element. Low demand and a relatively high price meant that this project was a failure for Volkswagen.

VEHICLE SAFETY

The first-generation Volkswagen Transporter was supposed to fulfil the simple tasks of a basic utility vehicle, providing enough space to move people and products around, while remaining affordable. The demands on the second generation were more than this. As the amount of traffic increased on the roads, safety features became more and more important.

T2a: Crash test.

Volkswagen quality is well known: all new safety features were substantially tested in simulations or crash tests before they became part of the volume production. From August 1969, in the event of a head-on accident, the new safety steering column would snap at its rated break point, to reduce the risk of the driver getting injured.

The T2 also got a double-jointed rear axle as standard equipment, providing the Bus with the comfort of a passenger car. In 1971, the T2 was fitted with larger rear lights replacing the small ones and, after the factory holidays in 1972, all Buses got new bumpers with a deformable area at the front.

T2b Panelvan prototype for the USA.

2

prototypesandunique models

In the automobile industry prototypes are the very first models of a vehicle, the master for series production. Very often the decision-makers have a prototype redeveloped over and over again, before they finally accept the result. Some of the prototype Buses were really bizarre specimens, but unfortunately only a small number have survived. This chapter covers some of the known and unknown prototypes of the T2.

T2 WITH FOUR-WHEEL DRIVE

Without the approval or knowledge of the former board members of Volkswagen, two passionate VW engineers, Gustav Mayer (known as ‘Transporter Mayer’) and Henning Duckstein, secretly developed an allroad vehicle based on the VW T2. This unofficial project was referred to internally as EA 456/01. First tests were made in the Sahara desert in 1975/76 with a red and white T2b Kombi. The test drives began on 25 December 1975. Starting the trip in Tunis, via El-Oued in Algeria, the route lead to the Grand Erg, a type of desert with impressively high dunes (over 400m high), ending in Hassi Messaoud. From there they came back to Tunis, and then shipped the Bus to Genoa in Italy. The extended try-out, over 800km, and difficult circumstances were mastered by the T2 without any problem.

T2b four-wheel drive.

Unfortunately, the development of the T2-Allroad was unofficial and occurred at the end of the T2’s production span. The resultant Bus tested in the Sahara desert remained one of five prototype allroad vehicles that never went into series production. How ever, VW would go on to use the knowledge they had gained from this inventive project, building an allroad vehicle in the third Transporter generation.

Four-wheel drive, exhaust pipe in bumper.

After some extensive research, two four-wheel-drive Buses based on the T2 have been discovered. One is exhibited in the VW AutoMuseum in Wolfsburg, while the other is owned by a German private collector.

The T2-Allroad had a standard 50hp engine, and a number of distinguishing features, as follows:

sheet metal tub and protecting runner under the front power train;

four-gear transmission (the gearshift pattern corresponding with the standard fittings);

torque converter;

the cardan shaft to the modified rear axle transmission was placed in the front;

the front wheels had a lockable drive element;

16in wheels;

the exhaust pipe was integrated in the bumper;

power lock differential;

the standard front axle suspension was modified;

wade depth of about 500mm;

three extra instruments in the dashboard: oil pressure switch, tachometer, differential oil pressure switch.

Fuel consumption (measured on the later prototype with 2000cc-carburettor engine) was 13–16l/100km and maximum speed was 115–120km/h. Its climbing ability (max.) was 77–94 per cent at 1,900kg gross weight, and 63–78 per cent at 2,300kg gross weight.

Over the years, five prototypes – three Kombis and two Westfalia Campers with a pop-up roof – were built. They had the following German licence plates:

T2b Kombi (Type 22): WOB-VK 25 (red/white); WOB-VM2 (olive green); BS-JT 941 (red/white) T2b Camper (Type 239): WOB-VM89 (ivory); WOB-VA 73 (ivory)

In the years that followed, the T2-Allroad was gradually improved step by step, gaining a 2000cc-carburettor engine.

T2 KOMBI ‘SAFARI’

Following the four-wheel-drive prototypes, the sales department ordered a new study of a T2 ‘Safari’ from the development department. A prototype based on a T2b Kombi was assembled, featuring many details that were not available for the standard models. In the front, this prototype was fitted out with black lamp rings, bared head and fog lights. An electric cable winch was attached over the front bumper, and the searchlight that was familiar on the Ambulance was also included. Lateral guide rails and plastic casing on the wheel housing completed the look.

Front view

back view of the T2b ‘Safari’.

Like a ‘standard’, this prototype had a black roof-rack, lamella windows in the sliding door and on the opposing side. (These were initially used only on Camper Buses.) The windows in the back were made of clear plastic. On the back of the Bus the name ‘Safari’ was written.

The interior arrangement was very practical. Beside the sleeping bench, a foldable table was fixed on the inner body side. There were curtains at the windows. Some of these details were well known from the T2 Westfalia Campmobiles.

Interior: perforated sheet metal.

Interior: Safari model with spade.

The Safari was equipped with two pieces of perforated sheet metal, which made it possible for the Bus to drive on sandy subsoil, or even through the desert. A spade was also part of the Safari’s equipment.

C-rails on the inner body side and the partitioning wall behind the driver’s seat made it possible to fix heavy loads.

T2B PANELVAN USA

The T2 shown on page 5 is a curious-looking Bay Window Bus based on a US version of the Panelvan. Completely coated in a gold metallic paint, this Bay Window has a round window on each rear outer body side, borrowed from the shipbuilding industry. The interior of the cargo compartment, including the floor, the inner body sides, the inner roof and sliding door, were covered with brown carpet.

T2b Panelvan cargo compartment laid out with carpet.

KOMBI VW DO BRASIL

This Brazilian Kombi de luxe (see right) belongs to the Wolfsburg Stiftung Auto-Museum Volkswagen collection. It is a 1998 T2 7-Seater ‘Kombi-Lotação’ with a significant amount of non-serial equipment, and the following features:

bi-colour lacquering, with the main body in light green metallic, and roof in white;

steering wheel with the new VW logo;

interior trim, dashboard and seats in light beige;

leather upholstery;

chrome T2a hubcaps;

chrome bumpers;

whitewall tyres.

T2c Kombi VW do Brazil. Front view.

Interior layout.

Back view.

Cabin layout.

T2 KOMBI ‘VW DE MEXICO’

This prototype of a Bay Window Bus (see page 12) was a design model for a facelift of the Mexican T2 model. Note the front-turn signals right below the headlights – reminiscent of the T2a – as well as the large rear-view mirrors and rectangular headlamps.

Mexican T2 prototype ‘facelift’.

T2B OPEN-AIR BUS

For a very popular German television show called Der Große Preis Volkswagen produced a convertible-like Open-Air Bus, based on the T2b Kombi. Unusual were the small air-intake louvres in the back and the chequered seats. This Bus is now part of the collection of the Stiftung AutoMuseum Volkswagen, located in the VW factory in Kassel.

1973: T2b open air.

T2b Pick-Up: manual battery change.

T2b Panelvan ‘Elektro-Transporter’.

ALTERNATIVE DRIVE ELEMENTS

The oil crisis at the beginning of the 1970s, and the pressing shortage of non-renewable energy sources, forced VW to undertake research into alternative drive elements. Two sources of energy that were tested, among others, were gas and electricity. The Bus was used as a testing vehicle for such alternatives for one very simple reason: no other vehicle in the VW product range was spacious enough to accommodate the testing drive elements.

The electric-powered Bus was the only model to be built in a small-volume production. All other tested drive elements remained at testing level.

Electric Engine

The VW Transporter with an electric drive assembly was available as a Kombi (Type 23), Panelvan (Type 21) and Pick-Up (Type 26), and could be ordered at German Volkswagen dealers.

Electric engine.

Technical drawing of the electro Pick-Up.