Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Eye Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Charlotte Metcalf has made documentary films all over Africa, and her director's eye for unforgettable people, location and attention to detail now transfers vividly to the printed page. We feel the heat, smell the smells, and sweat with Charlotte as she battles against bureaucratic inertia and incompetence, hostility and political pressure to record the often unwelcome truth. Charlotte's journal, like her award-winning films, is a close-up of Africa's deep-rooted problems from survival issues like AIDS, famine and cholera, to the unspeakable and ritual maltreatment of women. She presents a moving picture of African heroism in the face of the kind of suffering we would all prefer to walk away from but know we no longer can. This is a book for anyone who cares about the human condition.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 571

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2003

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Copyright © Charlotte Metcalf 2003

All rights reserved. Apart from brief extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher.

Charlotte Metcalf has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Walking Away 1st Edition October 2003

Published by Eye Books Ltd 29 Barrow Street Much Wenlock Shropshire TF13 6EN website: www.eye-books.com

Set in Frutiger and Garamond ISBN: 1903070201

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

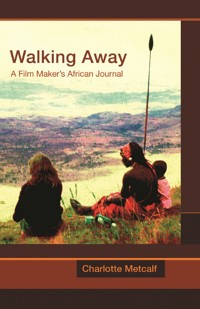

Cover photograph with kind permission of Michael Keating Author photograph by Matt Holyoak

In loving memory of Peter Parker who was the first to encourage me to write this book

Acknowledgements

Thanks to:

Michael Keating for showing me Africa in the first place; Robert Lamb and Jenny Richards for sending me on all those African assignments that make up much of this book; Hugh Phillimore for his patience, support and faith in the book; Roly Williams for introducing me to Eye Books; Gordon Medcalf, my saintly and inspired editor; Dan Hiscocks, my publisher whose enthusiasm and patience are limitless; finally to all the Africans who so generously allowed me into their lives and whose stories form the heart of this book.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Lenny Henry

PRELUDE TO ADVENTURE

1 DOGSBODY BEWITCHED, Kenya

2 THE TRANSPORT OFFICERS, Zambia

3 CONSENTING ADULTS, Zambia

4 BLIND LOVER, Zambia

5 THE RED TERROR, Ethiopia

6 THE TORTURED, Eritrea

7 A THANKLESS TASK, Uganda

8 THE UNKINDEST CUT, Uganda

9 WELCOME TO WOMANHOOD, Uganda

10 WHITER THAN WHITE, Zimbabwe

11 EDUCATING LUCIA OR ‘A’ IS FOR AFRICA

12 FOUR WEDDINGS AND A SHEIKH, Nigeria

13 AMINA, Ethiopian Somaliland

14 SIX AFRICAN DREAMS, Ghana

15 YOUNG WIVES’ TALES, Ethiopia

16 SCHOOLGIRL KILLER, Ethiopia

17 SCHOOLGIRL IN THE DOCK, Ethiopia

18 GREEN FAMINE

19 LIVING WITH HUNGER

EPILOGUE

ABOUT EYE BOOKS

Foreword by Lenny Henry

One of the downsides of being an ‘International Megastar’ is the constant begging and demands on my time. I thought once I had started doing Comic Relief people would leave me alone thinking … “That Lenny - he’s a good chap doing his bit.”

Eye Books chased me hard in order to get me to write this foreword. They kept on saying how the book gets away from clichés and gets under the skin of Africa’s real problems, away from the perceived ones. How it highlights the seriousness of the problems whilst being an antidote to cynicism because it shows how the people are clearly so capable if given the chance.

They also banged on about how in the same way that I appeal to many millions to do something, however small, that will make a massive difference to the receiver, I should take some of my own medicine and realise that me supporting this book was doing what I asked of others on Red Nose Day. A small something that could make a BIG difference.

Having now read Charlotte’s book I realise they were right and offer my wholehearted support. Walking Away vividly brings to life some of the real issues facing Africa. It also celebrates the amazing spirit of the African people.

This is an important book. Hopefully it will show people why we do what we do and inspire some who read it to go out and make a difference, to do something positive to help this beautiful continent. Too many just walk away.

“The best part of the job is when you feel you may have made a difference. The hardest part is when you have to walk away”.

Charlotte MetcalfLondon, 2002

RELEVANT COUNTRIES WITHIN THE AFRICAN CONTINENT

PRELUDE TO ADVENTURE

Drums throb and the crowd coils round a group of dancing women, shaking their shoulders and hips in a sensuous frenzy. Those closest to the dancers clap with rhythmic intensity, echoing the insistent beat of the drums. The women pant and sweat, though it is cool and a grey sky hangs low over the plain like a damp dishcloth.

Bill, the cameraman, and I work our way through the throng, pushing into a breathing, pulsating wall of flesh. We reach the dancers in the centre. Someone has gone to fetch the bride. The drumming and the dancing become more frantic.

The father of the bride is a tall, skeletal man in a ragged jacket. He grins proudly, showing a mouthful of rotten teeth glinting with metal. He stands with his daughter in front of him, his hands protectively on her shoulders. The bride wears an exquisitely embroidered white, woven dress and heavy silver jewellery with custard-coloured amber beads. Black kohl is smudged round her eyes.

She looks at the dancers, then at us and spots the camera. Her father pushes her towards us. Her mouth quivers and she begins to cry. She opens her mouth and bawls. Tears pour down her face in inky streams. The weeping bride is just four years old.

I am appalled. What are we doing here, with our intrusive camera, prying into another alien culture we barely understand and adding to the misery of this frightened child? How has my erratic path led me inexorably to this throbbing clearing in the Ethiopian uplands?

The trail begins twelve years before, the day I first arrive in Kenya…

The plane doors open, and in surges the fire-hot smell of Africa - woodsmoke, charred meat, rancid butter, leather, sweat and dung. I breathe it in and step out into the glare, the heat and a chapter of my life that is to change me in more ways than I can imagine.

It begins inauspiciously. I eat Brown Windsor soup, boiled fish with overcooked vegetables and tapioca pudding in the panelled dining car of the night train to Mombasa. At Watamu Beach on the Indian Ocean I slather myself in locally produced suntan oil and spend three days in bed with acute sunburn. Thus I learn the first important lesson about Africa, that the sun is vicious and malignantly potent.

Things improve rapidly. I fly in a tiny plane to Lamu, a somnolent, golden island off the north Swahili coast, fragrant with spice, jasmine and charcoal. There I lie in a hammock and watch wooden sailing dhows glide past on a lacquer-smooth sea luminous as mother-of-pearl in the setting sun, while the cry of the muezzin mingles with the early evening woodsmoke as it drifts up to my rooftop from the mosque below.

I plunge deep into the bush to stay at George Adamson’s camp, where each night lions gather to be fed. George looks like a Biblical prophet. Long white hair and beard frame a narrow El Greco face from which blazes a pair of shrewd blue eyes. He wears nothing but a loin cloth on a sagging, leathery torso, and his toenails are mustard-coloured talons, strong as horn, so long that they curl over each other.

Every dusk George goes to the perimeter fence with a bucket of meat. It seems wholly implausible that this boney, withered Elijah can summon the Lords of the Bush with a simple bucket, but some nights we end up with nine or ten lions just a few feet away, purring and frolicking about like kittens.

From there I drive a Landrover through the bush to the camp of ‘the leopard man’, Tony Fitzjohn, who is dedicated to saving the elusive Kenyan leopard. With his mane of bleached hair and muscular torso, Fitzjohn so resembles Tarzan that he once played the role in a locally produced B movie.

One morning he suddenly yells to me to run for cover. A female leopard, jealous of Fitzjohn’s Australian air hostess girlfriend, has leapt the high wire fence and now crouches in the compound, flicking her tail in readiness for confrontation. Cowering behind a door, I hear snarls, grunts and growls - from both Fitzjohn and the leopard - thumps, more grunts and breaking glass.

When it grows quieter I peek out. They are rolling around on the ground, entwined. One of Fitzjohn’s arms is bleeding, but the leopard is now purring throatily, eyes narrow with pleasure. Wooed and placated, the leopard goes. The air-hostess stays.

Back in Nairobi I swig beer with white cowboys on the terrace of the Norfolk Hotel, and sip gin and tonic amidst the floral chintz and cut glass accents of the Muthaiga Club’s drawing room. Here I encounter Surrey golf club etiquette in the wilds of sub-Saharan Africa. I lounge on elegant verandahs surrounding heavily guarded colonial mansions in the lush white suburbs of Karen and Langata. I listen to Karen Blixen’s Kikuyu manservant, Kamante - immortalised in Out of Africa and now old and grizzled - sing at a party.

Italian photographer Mirella Ricciardi takes me under her wing and together we visit the artist Peter Beard in his sumptuous, cedar-scented tent. Lounging against cushions on his teak deck, I think this is about as glamorous as life gets.

I travel north to Isiolo to help out with famine relief. It is my initiation - compared with what I will meet later almost a gentle one - into the massive range and extent of Africa’s problems. I am deeply perturbed by the Giacometti silhouettes of the Masai mothers and the stick limbs of their babies, and also hideously conscious of my meaty white thighs in shorts and my juicy bare arms.

After a while the brisk British matrons stop weighing babies and distributing sacks of grain. I am shocked when they open tupperware boxes and picnic on hefty sandwiches in front of the starving Masai. When I feel unable to join in I am quickly reprimanded:

‘If you don’t keep your strength up how on earth will you do your job properly?’ tuts a stern woman with an iron grey perm. Meekly I eat a ham bap.

In Maralel I meet Wilfred Thesiger, who lives in a compound surrounded by his African ‘family’. In the thudding heat he emerges from his thatched earth hut wearing a three-piece tweed suit and polished, lace-up brogues. Manipulatively, but gratefully, he purloins all my paperbacks.

I sit in companionable silence with an ochre-painted, beaded Samburu warrior on an escarpment overlooking the vast Rift Valley. I drink milk and blood in a Masai boma. I chew the mild narcotic mirar on an all-night bus. I water-ski amongst crocodiles on Lake Baringo.

By the time I arrive back in London I am hopelessly, and as it turns out permanently, under Africa’s spell. Later, when I am offered a job in Nairobi working as production assistant on a documentary film, I do not hesitate.

1 DOGSBODY BEWITCHED

Kenya

‘No-one else wants to do it,’ says my agent. ‘It sounds a bit dodgy.’

I don’t care. I can’t wait to get back to Africa. I set out to meet Uru, the son of my prospective employer, Sharad Patel.

Uru is just over five feet tall. His face is child-like and almost beautiful, but spoilt by a sullen, exhausted expression and the marks of a dissolute lifestyle - puffy eyes and a wan complexion. I brace myself to be grilled. Instead he looks me up and down appraisingly and asks if I’ve ever been to Kenya before.

‘Yes,’ I say, ‘I loved it.’

This seems to have the desired effect. He stands up and grabs a very big bunch of keys.

‘Let’s go,’ he barks.

He drives me to buy my air ticket in a white Mercedes that dwarfs him. It is hard to believe this pint-sized playboy is really in a position to hire me, but fifteen minutes later I am outside the British Airways office in Regent Street, a ticket to Nairobi in one hand and a wedge of cash in the other.

‘Ciao,’ says Uru, ‘Have a good time!’

His Rolex glints as he waves goodbye. I still have no idea what the job entails.

Three days later I am at the New Stanley Hotel in Nairobi where Graham, my director, is waiting for me. We sit in the Thorn Tree café, in the shade of the famous tree which has messages for travellers pinned optimistically to its trunk. Waiters in green uniforms, trays held high, weave around groups of khaki-clad Americans studying their guide books between safaris. I need a cup of coffee, but Graham looks as if he needs something stronger. His eyes are red and his hand trembles as it strokes his straggly grey beard.

Graham is a cameraman who has not directed before, nor has he been to Africa. He landed the job because he has made in-house corporate films for an airline. He asked the Patels for a British production assistant and here I am.

‘Am I glad to see you!’ he says. He smiles ingratiatingly, showing stained teeth.

‘It’s been chaos here,’ he goes on, ‘Working with these blacks is like trying to deal with a bag of monkeys.’ My heart sinks.

Later that day we are sitting in front of Sharad Patel’s substantial desk. Though small, Sharad is stocky and upright with a head of thick grey hair. A pair of spectacles lends his round face an owlish air. He treats Graham with deference. Towards me he is polite but dismissive.

Along with all the other Asians, Sharad and his family were thrown out of Uganda by Idi Amin. They fled to Kenya. Sharad is a formidable wheeler-dealer and networker who thrives on social contacts and government connections. Within just a few years his company, the Film Corporation of Kenya, has made two feature films and a horde of commercials, documentaries and educational films.

The offices are in Mama Ngina Street above the Red Bull, a rather dreary Spanish restaurant which - despite excellent tortilla and Rioja - is often forlornly empty. Sharad is inordinately proud of the movie he made about Idi Amin and the promotional posters for it are framed and displayed on the office walls. They show a crude, coloured drawing of Amin, eyes bulging and mouth foaming, with an Indian wriggling on the end of a bloody bayonet.

There is also a poster for Bachelor Party starring Tom Hanks, with which Sharad’s eldest son Raju had something to do. He is apparently big in Hollywood. Raju is expected in Nairobi any day, and meanwhile the middle son Viju is to look after Graham and me.

While Uru is living it up in London’s casinos and the Patel mansion on the North Circular, and Raju is mixing with the stars in Los Angeles, Viju is stuck at home working for Daddy. Sharad also has a daughter, aptly named Pretty, who is somewhat over-protected, and kept at home with her mother while Sharad seeks a husband for her.

Meanwhile it is rumoured that Sharad gallivants with Iba, the office accountant, a cheery, roly poly woman with a squeaky voice. She has a London flat in Oxford Street of which she frequently boasts. She sits in a pokey back room from which she dispenses petty cash from metal boxes which she unlocks with a substantial bunch of keys she keeps on a chain under her sari.

The Film Corporation owns several mobile cinemas. They travel all over Kenya, setting up screens in remote villages and attracting huge rural audiences. This ability to ‘spread the message’ gives Sharad leverage when money raising. Now the Kenyan post office has stumped up a large budget to make a series of films - some television commercials and a long documentary to explain how the post office works. One of the most common problems is that people send letters addressed, for example, to ‘Mr. Mkwori, Nairobi’ and expect them to arrive. The Lost Letter Room is overwhelmed.

The films are also to encourage and teach people how to use pay phones and faxes. Graham is to shoot the films, with Viju overseeing him. When available, Sharad or Raju will direct. The rest of the crew is Kenyan, apart from James, a nineteen-year-old British public schoolboy on his gap year who acts as a technical assistant.

Despite my title of production assistant I resign myself to being a decorative dogsbody. I am so happy to be back in Africa that I don’t really care. I tolerate Viju shouting at me when I spell Technicolor with a ‘u’, English style, on the camera report sheets. Later I don’t even protest when I get the lowest and humblest credit they can give me: ‘Runner’.

Two days after my arrival I turn twenty-nine. Graham invites me to dinner. I need to be on good terms with him if we are to work together successfully, so I accept. Graham arrives for our date wearing a white three-piece suit with a kipper tie. He has combed his long grey hair, but he still looks like a rumpled Bee Gee.

The Film Corporation only pays our per diems if we eat in the hotel so rather than spend his own money on a restaurant, Graham opts for the New Stanley Dining Room. It is gloomy and oppressive. The carpet is dark brown, the floor-length curtains orange and violently patterned. The waiter scurries forward and ushers us to a corner table amongst dusty pot plants. He lights candles with a flourish and smiling wishes us a pleasant evening. Graham asks for the wine list.

‘I’m not paying that for a bottle of French plonk,’ he says, ‘It’s extortionate!’

He orders palm wine instead. It is filthy.

We attempt conversation. He tells me about his wife and children and runs me through his CV. There’s more moaning about blacks being incompetent. The dingy lighting is giving me a headache. The over-decorated cod is tasteless and soggy. I am depressed. I drink the palm wine.

Next day work begins in earnest. The team gathers at Mama Ngina Street. George Githu, the production manager, wears a tartan tam o’shanter with a red pom pom. On top of a very thin, six foot four Kikuyu it looks hilarious. I like him immediately. I also meet Mohammed, the handsome focus puller, Gibril, the grip, and various other electricians and camera assistants. It is immediately obvious that the Africans are on very low wages and that they are to be treated very differently from us whites.

‘It’s always the way,’ says George cackling, ‘Old man Patel is notorious.’

The Patels are very hospitable to Graham, James and me, and we frequently lunch at their mansion. It is a glitzy affair, full of shiny gilt, gold-plated taps, cut crystal and marble. While the Kenyan crew eat basic African food on the stoep outside, we are treated to fragrant, delicately spiced curries in the airy, marbled dining room. Sharad’s wife and the exquisite Pretty wait on us. I learn to eat Indian-style, scooping up the curry and rice with a deft twist of fingers and thumb. It seems to taste better that way. Graham persists in asking for a fork.

Towards the end of the first week, the long-awaited Raju arrives from Los Angeles. He is sleek behind designer sunglasses, sweating slightly into an olive green silk shirt. His teeth gleam when he smiles. His accent is American. When he directs, he likes us all to behave as if we are on a big movie set.

Raju directs a scene in a metal foundry. The African workers look bemused to be treated like Hollywood extras, but take it in good spirits. It isn’t every day that an Indian man in gold jewellery turns up with lights, cameras and a crew including three whites, just for a couple of shots of them smelting whatever they are smelting in their furnace. As Raju repeatedly shouts ‘Action!’ they become more amused and are soon acting their socks off, hurling irons into the fire with exaggerated vigour. Raju is thrilled with the results and takes us all for a drink afterwards to celebrate.

I am becoming friendly with our technical assistant James. To begin with I am wary of his public schoolboy swagger. He tends to show off his Swahili or his superior knowledge of Kenya. I am infuriated by the way he comments daily on what I am wearing. He takes a particular fancy to my denim jacket. However, I do not have a car, and I’m stuck in the hotel every night because of the per diems arrangement. When James suggests taking Graham and me out for the day one weekend, I accept gratefully.

We go to the Nairobi Game Park and then to a country club for lunch and a swim. After the dusty bustle of Nairobi I am glad to be lounging in the dappled shade of a jacaranda tree. I can hear James splashing around in the pool and I can smell jasmine, and also the barbecued meat we will eat for lunch. I am surprised that Graham allows James to pay. His frugality is starting to irritate me. I am frosty with Graham but he seems not to notice, and back at the hotel that night he invites me to his room.

‘How about a perfect ending to a perfect day?’ he suggests as we stand together in the lift. I flee.

Next day I go to Iba and beg to be allowed a car. I also ask to have my per diems paid in cash so I can eat out. Iba is a tough negotiator and dislikes parting with money but I persist. By mid-morning she is reluctantly counting out a wad of Kenyan shillings and by lunchtime she is telling Viju to give me a set of car keys. I am free at last.

My own battle over per diems alerts me further to how little the African crew are being paid compared with us expats. Rashly and naively I decide to talk to Sharad. He is livid. His success is based on shrewd, frugal management and he doesn’t need the dogsbody telling him he is not paying people enough.

The upside of the very public dressing down which follows is that it endears me to the crew. Shortly after this, Jibril, the grip, asks to borrow $100 because his wife is in hospital. I am reluctant to dip into my funds - by British standards I am being paid very little - yet I have no concept of how to refuse him. On the one hand it is racist not to trust him to repay me. Equally, it is racist to feel obliged to lend him the money for fear of being politically incorrect. In the end, I lend him the $100. Viju finds out and shouts at me. He tells me I am stupid and deserve never to see the money again.

Two nights later Jibril comes to the New Stanley, pays me back and invites me home so his wife can thank me. In a shanty town on the outskirts of the city he leads me through a warren of narrow streets. Ragged little boys kick footballs around in the dirt, their bare feet grey with dust. Women lope home chattering with each other, carrying plastic jerrycans of water on their heads. Skeletal cats crouch over mounds of evil-smelling garbage, and a dog with a broken leg and sores round its eyes barks at us as we pass.

Jibril lives with his entire family in one small room that smells of sour milk and urine. Dressed in a pristine white blouse Jibril’s wife makes tea on the communal stove outside and then perches on an upturned crate to watch me drink it. I sit on the bed amongst the children, who gaze at me solemnly as we chat. It is all rather formal. Then one of the little boys gives my hair a curious, experimental tug. It breaks the ice and we all laugh. I am glad I lent Jibril the money.

Encouraged by the friendly atmosphere on the set, Mohammed the focus puller declares he is in love with me. Every day he stands with his head bowed, his posture forlorn, begging me to pity him. Whenever I am within earshot he pleads with me.

‘Just one date. Please Charlotte, I am hurting inside, please help me,’ he whispers. Eventually I capitulate, partly because he wears me down, partly because I am keen to spend more time with Africans away from work. Besides, Mohammed is undeniably handsome.

He takes me to a darts match in one of Nairobi’s cheaper hotels. I am the only white person there. He spends almost his entire week’s salary on beer and lines up the brown bottles on the table in front of us. Though I do not like beer very much, it’s a lot better than Graham’s palm wine, and I drink as much as I have to to be polite. Mohammed says very little but sits proudly with his arm round me and surveys the room. I feign an interest in darts.

The evening ends fairly disastrously. I have tried chatting to Mohammed about everything from darts to his ambition to be a cameraman. He interprets this as a come-on and when I resist his unexpectedly forceful advances, he attributes my rejection to the fact that he is black. I am furious.

The next day he is sullen and angry and my attempts to mollify him fail. Later, avoiding my eye, he asks to borrow money. I lend it to him without question and tell no-one. He never pays me back. The incident dents my confidence. I feel a fool, tricked and belittled by cultural codes I am unable to decipher.

Nine months later Mohammed will die of AIDS. Three months after him four others on the crew will also be dead - the great epidemic has started and none of us realise how closely it will touch our lives.

James has followed Mohammed’s interest in me with amusement, and teases me about it. I find his light-hearted attitude a relief after the intensity of Mohammed’s attentions. One night we go to the cinema together, and afterwards James asks if he can crash out in my room because he has no transport to go back out to Langata. I do wonder how he normally returns home, but think it would be prissy to refuse him.

We talk all night, and two days later he moves into my hotel room. No-one is as surprised as I am by this turn of events. The last thing I expected was to fall for a boy just out of school, but there is something delightful about abandoning the responsibilities of being a woman nearing thirty and becoming a lovestruck teenager again. And I am in Africa - miles away from the cares of my real life in London. I have the rest of my life to be sensible.

We try to keep our relationship secret, but it is difficult with Graham in the same hotel. He is angry when he finds out. He resorts to drink and the moral high ground in swift rotation. His temper becomes worse, as does the reek of alcohol that hangs around him like an oily veil.

A week later we are filming in a big open-air market which specialises in cheap metalware. As far as the eye can see there are piles of metal pots, pans and braziers for burning charcoal. The constant din of beating and clashing metal jars my nerves. Viju stands on the roof rack of our truck, bellowing at the crowd through a megaphone. I am standing clutching my clipboard when a huge man looms up and jabs me in the chest with his forefinger:

‘You! You muzungu! Even me, I do not like your face!’

People snigger and the crowd starts to swell around us. Faces turn hostile. Viju jumps down from the truck and begins to shout and push people away. Someone throws a stone. I am hemmed in against the truck. People are so close that I can smell the scraps of meat between their teeth.

Without warning Graham turns and runs. He looks old, tired and frightened as he clumsily hurries away. This simple unheroic act breaks the tension. The children start to laugh, and soon everyone is jeering at Graham and hooting with mirth. For Graham this is the last straw. He announces he has had enough and it is time for him to go home.

The night before he leaves Graham takes James and me out to a Chinese restaurant and presents me with a silver elephant hair bracelet and ring in a green silk pouch. I am overwhelmed, mainly with feelings of guilt. I have recoiled from his racism and have been neither supportive nor sympathetic. Now he is being gracious and generous in defeat, and I feel truly sorry.

Any thoughts I had of returning home have evaporated. I have earned just enough money from the shoot to survive a couple of months, and as soon as filming ends James and I take a plane to the coast. As we land in Mombasa, I have no idea where we are going or for how long.

We rent a motorbike and take a hut on Diani beach close to some of James’s teenage friends. The days pass in a sun-drenched blur. At night we burn money at elegant beach bars, go to parties or dance with prostitutes and Masai tribesmen in a sleazy nightclub called Bush Babies. It’s like a golden dream, but occasionally I find myself yearning for the greyer reality of adulthood.

I am relieved when we go back to Nairobi. I should call it a day and go back to London but I am still paralysed by Kenya’s potent spell. We move in with Joss Kent. Heir to the Abercrombie and Kent fortune, Joss is also blessed with charm and looks. In the lush suburb of Karen his father has a house called Bahati, nestling amongst avocado trees behind high, white walls swathed in bougainvillea. In his father’s absence Bahati is Joss’s palace.

We spend our days by the pool at the Muthaiga Club, picnicking in the Ngong Hills or lounging in the Bahati sauna, which we enliven by pouring vodka onto the hot coals. Nightly, regular as clockwork, the golden girls and boys of Nairobi arrive to party. We usually drift on to dance at Bubbles nightclub or play blackjack at the Casino. It is a decadent lifestyle based on money and idleness. I don’t care. It is a delicious novelty and I am making up for my own lost teenage summers, spent in dreary typing jobs to pay my way through university.

Eventually I am seriously broke, but before facing London again I badly want to go on safari, so James and I set off for the Masai Mara with his friend Paddy. At this time the game reserves are full of well-heeled American tourists and going on safari is prohibitively expensive.

We plan on camping, but arrive after dark when it is forbidden to drive around the reserve. We have no choice but to head for one of the lodges. We cannot afford the luxury tents or cabins at $70 or $80 a head, but having driven so far we are determined not to turn back. We decide we will split the cost of a single cabin. I will pose as a lone woman and James and Paddy will sneak in later.

The first part of the plan works, and I move into the hut alone. Alone that is unless you count the tarantula with whom I share the tiny lavatory for an hour or so, me sitting on the loo and the tarantula’s hairy legs curled round the inside doorhandle. Eventually I manage to scramble carefully over the partition, but it takes me a long time to recover.

Finally the boys find their way to my hut and we settle down, three to the bed, for an uncomfortable night. At dawn we are woken by a screeching, tearing noise followed by thumps and hysterical shouting. A bull elephant has blundered into the camp and is crashing around, knocking down flimsy walls and causing havoc. The management evacuates us all, so we are discovered, given a dressing down by the hotel manager and told to leave.

We set off into the bush and look for somewhere to camp. We meet some rangers who, for a small bribe, show us a place by the river where we can pitch our tent. I haven’t camped since I was at school and have forgotten how much I used to enjoy it. We sit round a fire under the stars, sipping icy cold beer from the coolbox as sausages split and sizzle on the griddle. A family of hippopotamus snorts comfortingly in the river and watches us, eyes red as embers in the dark. I fall even more hopelessly in love with Africa.

Two nights later James and I have a fight. Later I will not even remember what it is about, but he slams his hand down so hard on the car bonnet that he dents the metal. I run tearfully into the bush. It isn’t till I stop that I realise I have no way of finding my way out again. I listen for the sound of voices. Nothing. I daren’t sit down, for fear of snakes and insects. I was born without a sense of direction so I do not even consider retracing my steps. I stand there for what must be about an hour, acutely conscious of every rustle. I imagine a lion behind every bush, a leopard in every tree. It isn’t until nearly dawn that they finally find me.

When I climb into the car, it is all over between James and me. A few days later I am on the plane home to my parents, who are very worried as I am long overdue. I feel irresponsible, selfish and contrite. Not before time. As for James, I am sure I will never see him again. I am wrong - but that’s another story.

Back in London I felt dislocated and depressed. I was not ready to settle back into the comfortable but muffling security of my home city. I went back to work as a freelance pop promo producer, but day-dreamed about Africa. I became a Kenyan Ancient Mariner. I had what the French in Nairobi refer to as ‘le virus’. I was still bewitched and nothing but another dose of Africa would make me feel better again.

Just a year later I am back in Nairobi, having persuaded the managing director of Island Records that the British reggae band, Aswad, will benefit enormously from a video shot in Kenya. So here I am, a producer no less, at the airport to meet the three main members of the band - Brinsley, Tony and Drummie. I can see their tall hats stuffed with dreadlocks bobbing above the crowd. Children cluster around, mouths slack with curiosity - Rastafarians are an unusual sight, especially ones like these in flamboyant boots and expensive leather coats.

We film first at the Carnivore, an enormous Brazilian-style restaurant and nightclub, just off the main highway out of Nairobi. It is strikingly laid out in a series of open-sided thatched huts, where every conceivable animal is grilled over open fires and served at the table from swords. You can refuse what you like but the waiters keep coming, brandishing blades heavy with chunks of cow, giraffe, zebra, impala, wildebeest, crocodile tail, buffalo, ostrich, kudu and many more.

American and British voices drift through the charcoal smoke, ‘Giraffe - how gross!’ or ‘Crocodile? You’ve got to be kidding!’ but there are always chicken wings or fish and a stab at salad for the squeamish. True vegetarians are best advised to stay at home.

Aswad play a set and go down a storm. The crowd swells round the stage, singing along and waving their arms. Afterwards Aswad disappear into a sea of surging, gorgeous girls.

After our initial success at the Carnivore we leave Nairobi to film at Lake Magadi. As we drive out of the city the great red mountains rise ahead of us, shimmering in their glistening coat of heat and dust. Kenya reclaims me as I feel the landscape pulse with an insinuating, hypnotic, primeval beat.

Lake Magadi is like a furnace. The salt flats reflect bright white light. Within minutes pale faces are red, noses already blistering. Aswad sweat into their heavy locks. The British crew tie kikois round their heads like handkerchiefs which make them look like exotic versions of Blighty Boys at the Seaside on an Edwardian postcard.

We film Aswad performing with a troupe of local dancers wearing leopard skins and head-dresses, under acacia trees that throw their bony arms towards the sun in graceful silhouette. Long, white clouds scud across the sky and the lake shimmers pink in the ferocious heat. I am truly, madly, deeply in love with Africa again.

Back in Nairobi the band wants a night out so I take them to the Casino. A mountainous bouncer blocks our entry.

‘No hats,’ he says, folding his arms across his body. He has no neck above his bow tie, and his dinner jacket strains at the seams.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ say I, trying to sound like a woman in charge.

‘Why not?’

‘Regulations’.

The bouncer stares over my head impassively. Admittedly, the Aswad headwear is particularly lavish. Tony’s hat is in crocheted wool, the colours of the Ethiopian flag. Drummie wears a patchwork suede peaked cap in purple and navy with blanket stitching, and Brinsley a two tone leather affair.

‘But they’re Rastafarians, their hats are part of their religion. You wouldn’t throw a Sikh out for wearing a turban would you?’

No reaction.

A small crowd has gathered on the stairs up to the Casino Entrance. People are asking for autographs, or staring and making comments to each other about Aswad’s hats.

‘We’ll take our hats off then,’ says Tony.

The bouncer’s eyes bulge as he braces up for a fight.

‘You cannot come in.’

We try invoking Princess Diana and Aswad’s Buckingham Palace gig, to no avail.

‘What’s the problem, brother?’ Brinsley persists, stepping forward. The bouncer makes a sudden movement and we back off fast. The bouncer has the last word.

‘If you’re my brother,’ he shouts, then points at me: ‘What you doing hanging out with that white trash?’

Next morning we are up early to go to Amboseli Game Park to film another scene. After the night before we aren’t too sorry to be leaving Nairobi, but it is raining and no-one is in a good mood. We drive along in grumpy silence under sagging black clouds.

We plan to do some filming and return to Nairobi, but our journey takes us far longer than we anticipated because the rain has made the roads muddy and treacherous. By the time we realise we are lost, it is dark.

We drive on. The road crosses a seemingly endless plain of waist-high grass, till a small Masai boy with a herd of goats materialises in the headlights. He raises his spear and shows us a big, toothy smile. We stop to ask him the way - anywhere. He jumps happily into the back of the minivan and directs us through the bush for about five miles till we reach a small lodge. Then he scampers off into the dark again to find his goats.

In the lodge a sullen young man behind a makeshift reception counter tells us there are only three rooms available. We will all have to share. Aswad start grumbling again. They lay the blame squarely on me - this is a hopeless production, they want to go back to Nairobi immediately, they are fed up with this. I stand my ground, albeit shakily, and say that I will happily share with the camera crew and director, four or five to a hut. Surely they can at least share one, or even two, huts between the three of them?

As we argue, a woman slinks from the shadows behind us. She wears a stretch satin, flowered dress that clings to her sumptuous curves. She reeks of hair oil and gardenias. She smiles and leans languidly against the door frame.

‘Hello boys,’ she drawls, ‘ My name is Lydia. Do you want to play with me?’

She holds up a dart and thrusts it at them suggestively. Then she laughs mischievously, showing gold teeth. It is a throaty laugh, thick with sexuality. Brinsley, Drummie and Tony look like rabbits caught in headlights.

Tony clears his throat:

‘I don’t mind sharing a room,’ he says. Then they all start talking at once. Thanks to one small prostitute they agree to move into a hut together.

We regroup in the shabby little bar where Lydia is playing darts. The wooden tables are rickety, sticky and stained. A few other men are sitting around but they soon leave. At nine o’clock the power fails. Lydia chuckles and comes to sit with us. We wait in the dark till a boy brings oil lamps and candles. When they are lit the bar looks less seedy and rather cosy. Steaming bowls of goat stew arrive. We realise how hungry we are. There is nothing to drink but a dusty bottle of Grand Marnier, but its syrupy golden liquid tastes like nectar.

Just after Tony and Drummie have gone to bed a very old Masai man hobbles in, leaning on his spear. He stops and stares at Brinsley. He has seen plenty of white people before but never a black man with dreadlocks and leather trousers. He shuffles across the room and sits huddled in his red check blanket, looking at us with such earnest curiosity that it is impossible to be offended.

Brinsley is in an expansive mood after his fourth Grand Marnier. He greets the old man and in return receives a wonderful, ear-splitting, virtually toothless smile. Brinsley has a CD walkman with him. The old man points, indicating he wants to look at it.

‘Wait!’ says Brinsley, jumping up, ‘I’ve got an idea!’

He rushes out to the minivan and comes back with a Bob Marley CD. Like a scientist setting up an experiment he carefully puts the cushioned headphones over the old man’s head then adjusts the volume. When Brinsley is sure the old man is ready he presses the play button and Bob Marley’s Jammin thunders into the old man’s ears.

He freezes, eyes wide with shock. After about a minute, he raises a gnarled hand to the headphones and touches them gingerly, as if to check that he is not imagining them. He closes his eyes. He starts to sway. The swaying becomes more rhythmic as a smile spreads across his face. Strange noises emerge from his throat. Soon, his whole body is moving in time to Marley’s beat and the old man is singing along. I am moved by the extent of his delight. Momentarily, the greasy little bar becomes magical.

Meanwhile, Lydia has decided that John, the director, is the man for her. John is a strong, silent type from Birmingham with a down-to-earth approach to life but, like all of us, he has drunk too much Grand Marnier. He soon has his arm round her and is offering her a cigarette.

‘John, oh John!’ pants Lydia, as she snuggles into his armpit, ‘You know how it is when you split a chicken?’ She makes an alarming snapping movement with her hands.

‘This is how I am wanting to do with you tonight.’

She licks her lips and her eyes gleam in the lamplight.

She nearly has her way. She hunts John down to the pit latrines. He manages to eschew her embraces there, but about four in the morning I hear squeaks outside the hut I’m sharing with the crew. At first I think it’s an animal but it is Lydia.

‘John, John!’ she is whispering, ‘Wataka wewe - I want you!’

I go to the door and open it. Lydia’s smile disappears. She spits, says something obscene, then turns and stumbles off into the bush.

Next morning Brinsley, Tony and Drummie are all big eyes and drama.

‘Did you hear that big animal?’

‘Yeah, definitely some kind of wild beast.’

‘I couldn’t sleep at all,’

‘Must have been a lion,’

They are shivering with lack of sleep. The men we hired to help carry the equipment are very amused.

‘Simba?’ they snort, Majingo kweli kweli! A lion? The bloody fool!’

They fall about chortling.

‘They think there was a lion.’

‘Maybe it was a rat!’ More laughter.

‘What are they saying?’ asks Tony. I never tell him.

Back in London Aswad’s song was not a great hit, though the video was much admired. The world of pop videos was unlikely to take me back to Africa. Little did I know it would take me six years, and a career change via Pakistan and Afghanistan, to find my way back there again.

2 THE TRANSPORT OFFICERS

Zambia

I went to Zambia to direct a film about cholera for the World Health Organisation. The object was to draw attention to the escalating crisis and teach people how to defeat cholera. Since it is one of the simplest illnesses to cure, thousands of people were dying quite unnecessarily. I was excited about the project, believing it could educate people and put pressure on the government to act. Back then I still had a passionate belief in the efficacy of both film and the United Nations.

I arrive in Zambia with big ideas and a small budget. I expect it to look like Kenya, and I am disappointed. As my taxi drives into Lusaka there are no mountains, no monumental sculptural clouds hanging in an eternal sky, no giraffe lumbering across the road, no veil of rust-coloured dust blurring the horizons, not even a whiff of woodsmoke. We drive past shabby concrete housing and huge billboards saying ‘AIDS is everywhere,’ or ‘Stay alive - stay faithful’. People pick their way listlessly home along the railways lines. Goats root around in the sewage along the side of the road.

I book into the Pamodzi, an ugly, multi-storey hotel set in a walled garden. Thanks to my UN status I get ‘diplomatic’ rates, but it is a difficult place in which to be a lone woman. By the pool waiters hover insistently. There is a plague of mangy cats, some blind, others with limps, one with a bleeding mutilated ear. They whine pitifully and rub against me whenever I so much as contemplate a sandwich.

In the bar men wait for women tensely in the shadows, while couples canoodle in dark corners. The music is tinned and smoochy, the cocktails syrupy, expensive and served with little parasols and pineapple garnish. In the Jacaranda coffee shop trelliswork and dusty plastic ivy struggle to create a ‘patio’ atmosphere.

Despite the efforts of the smiling chef who presides over the hot plates, the food is uninspiring and over-priced - the ubiquitous Nile perch, soggy potatoes, limp salads, okra mush, stale bread rolls. The other white people, mainly aid workers or businessmen, eat hurriedly with bowed heads. They study reports or read books and then scuttle off with their briefcases. Zambians arrive in groups and stick together. I want to explore but feel marooned, not knowing how to negotiate my way downtown alone.

Unlike the empty evenings my days are frantic, organising locations and permissions, tracking down the right people to interview and trying to ascertain the full extent of the cholera crisis. Hiring a driver is beyond my budget and self-drive is not available, so I rely on taxis and choose a grizzled old man to drive me around. His taxi boasts a fringed, brown carpeted dashboard, fairy lights and a selection of beads, feathers and carved amulets dangling from his rearview mirror.

Every day I battle with bureacracy. I have to account for myself to endless hospital committees or representatives from the Ministry of Health. Daily I slog up the six flights of concrete, urine-spattered stairs in the United Nations building to obtain further written permissions or to justify myself yet again to another committee. One Zambian doctor, whose role I never quite ascertain, presents me with an enormous budget for his services, including a hefty per diem allowance. I despair of ever delivering the film on budget.

I am relieved when the crew arrives from Zimbabwe. I have to hire from Zimbabwe because there are neither equipment nor crews available in Zambia. The cameraman, Tzvika Rozen, is Israeli but has lived in Harare for over a decade. He has spiked hair and a pony tail and wears pink shorts. The sound recordist, Peter Maringisanwa, wears pristine, ironed Wranglers and a complicated camera assistant’s waistcoat full of pockets and flaps like an angler’s.

We start filming in George Compound, one of Lusaka’s overcrowded shanty towns with limited water and virtually no sanitation. A primary school has been turned into a makeshift cholera centre. It is a long, low building set in a parched garden. A guard in a white coat and wellingtons and wielding a gun stops us at the gate. When we say we want to go inside he laughs.

‘Aren’t you afraid? Don’t you know how infectious cholera is?’ he asks. As I wipe my feet on the disinfected rags at the entrance to the wards he looks at me with amused contempt, as if I were very, very stupid.

Inside the scene is grim. In the first ward men are lying on blankets on every available inch of floor, many attached to drips. Most are too exhausted to object to the camera. They gaze into the lens with eerie intensity. I can see Tzvika and Peter are shaken, but they do their job doggedly.

The women’s ward is worse. One woman is having violent diarrhoea into a red plastic bucket. Mothers lie weary and weak, cradling their stinking, dehydrated children. To identify them nurses have stuck plasters on the children’s heads with their names on them. The stench of disinfectant and excrement is sickening. Nurses in wellingtons lumber amongst the drips that festoon the room. In a corner, someone pulls a grey blanket up over the head of a woman who hasn’t made it. Once this was a classroom.

Because cholera is so dehydrating, people’s skins wither, particularly round the eyes and mouth and on the backs of the hands. Young women look seventy, their eyes sunk into pouches of puckered skin. The children are unusually quiet, lending the rooms a ghostly atmosphere.

Half way through the morning a delegation of South African businessmen from a pharmaceutical company arrives. They wear aviator sunglasses, crisp, short-sleeved shirts and pressed flannel trousers with shiny shoes. They insist on being sprayed with disinfectant. They even hold up their briefcases to be protected from contamination. Once in the wards they stand round the edges and will not go within six feet of any patient. Their caution is totally unnecessary. Well fed, well watered, healthy men like these will not catch cholera. Cholera goes for the malnourished, with weak immune systems. It preys on the poor.

When the South Africans have gone Hope, the chief nurse, offers us refreshment. She has been twinkling at Peter since we arrived. She regards him slyly out of the corner of her eye as she pours tea on the little stone terrace which surrounds the building. Tzvika grins conspiratorially at me. Peter never seems to grasp the effect he has on women.

Peter is chatting to Hope about her home village when a new patient arrives. Hope puts down her cup reluctantly and goes back to work. Just inside the gate a group of boys surrounds a wheelbarrow containing a heap of filthy rags. They have wheeled it ten miles. The rags materialise into a woman. Her name is Catherine. Critically ill and too weak to walk, she is carried into the ward by four nurses.

I want to follow a cholera patient’s story from arrival at the ward, and Catherine would be the perfect focus for our story but there now arises a familiar tension. For the good of the film I need to shove our camera in Catherine’s face, but my instincts tell me to leave her to suffer privately. The film-maker wins and Tzvika moves in. Happily, after a few days of treatment with oral rehydration salts, Catherine has recovered. We find her sitting up in bed, smiling, ready to go home.

As we drive back to the hotel we see a dilapidated car driving slowly towards us, a megaphone thrust out of the window. Children run alongside it shrieking with delight. Our driver translates the message blaring from the loud-hailer:

‘Beware of the faeces! The secret of cholera lies in the faeces - oh, yes my friends. I am telling you, never defecate under the mango tree and then eat the mangoes - this way you will contract the cholera.’

‘Overtake that car,’ I say at once. When you are filming a depressing topic, lively characters who can reinforce the message with a light touch are like gold dust. The man behind the megaphone is Kennedy Mbau, who has been a bodybuilder and once held the title of Zambia’s Mr. Universe.

‘I was unspeakably strong, oh yes,’ he says. Today he is a stooped middle-aged man with a ragged scar down one side of his face. After a member of his family died of cholera, he decided to dedicate his services to combating the disease. He speaks in stilted but passionate English:

‘My message to the people is as follows: I tell them to guard against any habit that can make them drink or eat faeces. Above all, they must retreat from those flies. Those flies are very bad. Flies are the transport officers of cholera. Oh yes, my friends!’

Flies are indeed transport officers and cholera spreads quickly in unhygienic conditions. The toilets at George Compound are disgusting and they serve hundreds of people. I want Peter and Tzvika to film them.

‘You’re joking,’ says Tzvika.

‘I don’t think so,’ laughs Peter.

Tvzika asks:

‘But how will people watching ever begin to imagine the stench?’

We cover our noses and brave the toilets. The concrete floor is slimed with urine. Cockroaches feast on coils of excrement and rustle amongst discarded twists of shit-smeared paper.

The meat market is another gruesome sight. Sheep’s stomachs fester in the sun. Cows’ feet, complete with hooves and fur, lie jumbled up in crates. Flies swarm round the oozing eye sockets of goats’ heads. Yards of slimy, yellow tripe, dripping scraps of gut lining and bladder hang from hooks. Stallholders wave pieces of cardboard lethargically above the stinking offal but the battle is lost and the victors are the flies, shiny, plump, hyper-active and buzzing about spreading cholera like wildfire.

The local bar, or ‘bottle store’, is equally hazardous. Outside a squat concrete shack an old woman in a woolly hat is stirring cassava beer in a rusty tin drum with a wooden pole. She laughs like a witch, which I assume is a sign of intoxication. Over her eyes is a milky film. Inside men are drinking vomit-coloured beer out of filthy plastic containers. A whoop of excitement goes up as I walk in. One man tries to stand and falls over. Others stand, staring and swaying. I doubt if they have seen a white woman in their bottle store before. One man, sweating profusely, the flies of his stained shorts undone, staggers up to me.

‘Madam,’ he shouts. ‘Give me one kwacha for beer!’

A roar of approval goes up from the crowd and then a woman in the corner starts screaming something incomprehensible. The crowd laughs obscenely as the man comes closer. I can smell the sour beer on his breath.

‘Madam,’ he insists, ‘Even I am thirsty. Give me beer.’

I am eager to escape, but out of the corner of my eye I see that Tzvika and Peter are filming away. I am creating a handy diversion.

‘Madam,’ says the man, angry and desperate now, ‘I am telling you!’ He grabs my arm.

‘Let’s go,’ says Peter, taking hold of my other arm.

There is a brief tussle and then we are outside again, surrounded by children excited by the commotion and noise.

The markets are full of traditional healers or witch doctors, taking advantage of the crisis to tout their wares. I had imagined chanting, sweating, feathered voodoo-men with rolling eyes. Instead they tend to be canny merchants in suits, with alluring smiles and reassuring blurb about their products.

At one stall a cardboard sign reads: ‘Get your cholera cure here’ in English. There are bowls full of feathers and little pieces of unidentifiable bone, chicken’s feet, powders, dried plants, leaves and roots neatly laid out on a blanket. On a stool in front of it sits a man in a brown suit. Our translator poses as a cholera patient.

‘I can assist you’ says the witch doctor in excellent English. He holds up a gnarled root that looks like a cross between a piece of ginger and a finger.

‘This is very good medicine for the cholera if you are purging and vomiting.’

‘How much are you charging?’ asks our translator. The witch doctor eyes our expensive camera equipment shrewdly. ‘Just 500 kwacha for one root,’ he says.

The vastly inflated price genuinely takes our translator by surprise. He tips back on his little stool.

‘500 kwacha? For only that one root?’

The witchdoctor shrugs.

‘Perhaps you prefer to die than spend the money.’

While traditional medicine can be beneficial, in the treatment of cholera it is of course an expensive waste of time. Immediate rehydration is the only cure. A mixture of water, salt and sugar is usually sufficient. We are still to discover why this simple message is failing to circulate round Zambia.

We fly up to the Copper Belt where Kitwe, the capital of the North, has been the worst hit area in the country. During the rains of November 1992 over five hundred people died. A driver meets us at Ndola airport and takes us straight to the Ministry of Health’s local representative, Patrick Mubiana. Mubi, as we nickname him, apologises for not coming to the airport himself. He is also a pastor and has been preaching his Sunday sermon. He is a plump little man with a high-pitched giggle that makes his body wobble like a jelly. He is passionate about ‘this terrible cholera business’ and is prepared to do all he can to help us film.

The road to Kitwe is straight, the landscape flat and dull. We see no animals except a couple of vultures picking at the entrails of a dog’s corpse on the road. Tribal dress has been abandoned in favour of Western clothes - brown slacks and anoraks for the men, skirts and nylon patterned sweaters for the women. Kitwe is a dismal frontier town. There are half-finished concrete buildings everywhere and it rains relentlessly, churning the roads and pavements to mud.

Mubi has booked us into the Edinburgh Hotel. The decor is a monument to the worst of the sixties. Tube lights are suspended from the ceiling. A swirling staircase leads up to the dining room. It has once been a ballroom and we eat lunch under an elderly glitter ball, next to a round stage framed by blue velvet curtains, now rotten.

My bedroom has a hole in the ceiling, a dripping pipe, broken air conditioning and a view of Kitwe’s sad main street. In the bathroom the ancient blue linoleum is peeling. My bed is soft and soggy. This is the best hotel in town.

Next morning we order fried eggs for breakfast. Half an hour later nothing has happened. Peter and Tzvika shout at the waiters and there is much scurrying but no eggs. Finally, an old man hurries out of the kitchen, bearing three plates proudly. He is sweating and apologetic. The plates are piled with bacon, sausages, tomatoes and beans.

‘There are no eggs,’ says Tzvika. The old man looks bewildered.

‘Where are the eggs?’ asks Peter.