Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

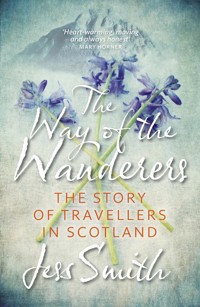

'Jess reveals a way of life that leaves the reader full of admiration' - Mary Horner Scottish Gypsies, known as Travellers or Tinkers, have wandered Scotland's roads and byways for centuries. Their turbulent history is captured in this passionate new book by Jess Smith, the bestselling author of Jessie's Journey and a Traveller herself. Her quest for the truth takes her on a personal journey of discovery through the tales, songs and culture of the 'pilgrims of the mist', who preferred freedom to security, and a campfire under the stars to a hearth within stone walls. The history Jess has uncovered reveals centuries of prejudice and shocking violence by settled society against Travellers, including the enforced break-up of families and separate schooling. But drawing on her own and her family's experiences as they wandered the glens and braes of Scotland, she also captures the magic and rich traditions of a life lived outside conventional boundaries.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 498

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WAY OF THE WANDERERS

JESS SMITH

was raised in a large family of Scottish Travellers. She left her old ways behind when she married her husband Dave, a non-Traveller. Her writing career did not begin until her three children left home to build their own nests. It was then she took the decision to write about her culture. Jessie’s Journey was the first book in her autobiographical trilogy, which continued with Tales from the Tent and concluded with Tears for a Tinker. She has also written a novel, Bruar’s Rest, and a collection of stories for young readers, Sookin’ Berries. Jess is a gifted storyteller and has shared her tales in live performances throughout Britain, Ireland and Australia.

First published in 2012 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Jess Smith 2012

The author gratefully acknowledges the Estate of Athole Cameron for The Gaun-Aboot Bairn; Mamie Carson for Keith McPherson’s The Muckle Stane; Robert Dawson for quotations from Empty Lands and unpublished documents; Mary McKay for A Life Long Gone; Andrew Sinclair for the quotations from Rosslyn: The Story of Rosslyn Chapel and the True Story Behind the Da Vinci Code; and Sheila Stewart for Belle Stewart’s The Berryfields o’ Blair and Glen Isla.

The moral right of Jess Smith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 078 4

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 565 9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Set in Bembo and Adobe Jenson at Birlinn

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

I dedicate this book to the ancestors of the Travelling People

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

The Inspiration

1 The Lochgilphead Tinker

2 The Beginning of the Journey

3 The Greens

4 Mansion on Wheels

5 Perth and the Romans

6 The Wandering Trail

7 Closing-Down Sale

8 The Broxden Curse

9 And On We Go

10 The Crieff Connection

11 Comrie and Beyond

12 The Dreaded Humpies

13 Clooty and the Ghost of Ardvorlich

14 East of Lochearnhead

15 Stories from Killin

16 Finn and St Fillan

17 Dermot O’Riley

18 From Kenmore to the Appalachians

19 The Picts of Kenmore

20 Weem Tales

21 The Urisks and the Brownie

22 Weem, Home of the Black Watch

23 Tales of the Tinker Soldiers

24 The Battle of Killiecrankie

25 War Memories

26 Balnaguard

27 The Caird

28 Cairds, Tinkers and Sinclairs

29 Gypsies

30 Gypsy Slavery

31 Next Stop on the Road

32 Descriptions of Gypsies from the Past

33 More Stories from Chambers

34 Simson’s History

35 The Cottar Folk

36 The Report That Condemned the Tinkers

37 Eradicating the Culture

38 Berry Fields o’ Blair

39 The Undesirables

40 The Next Attacks on Tinkers

41 Apartheid Education

42 No Life for Riley

43 No Room Here, Thank You

44 The End of the Road

Books Consulted

ILLUSTRATIONS

A Tinker mother and child

Gravestone of Gypsy chief Billy Marshall

‘The Tinker Widow’

The coronation of the Gypsy King, Charles Faa Blythe

Coronation of the Queen of the Gypsies

Tinkers at Pitlochry in 1899

A vardo, or horsedrawn caravan, is hauled through snow

The Good Samaritan

Tinkers camped in a cave in Elgin

Building a Tinker camp

My father’s Aunt Jenny, a hard-working Gypsy mother

A minister baptising a Tinker baby

Travellers moving camp

A camp of Highland Travellers at Pitlochry

A Mars Training Ship by the Tay Bridge

Balnaguard on the banks of the Tay

Berrypickers at Blairgowrie

Travelling show people

Granny and Hughie at the roadside

A travelling knife-grinder

A Gypsy multiplication table

My great-grandparents in the 1881 census

The Tinkers’ Heart in Argyllshire

The school for Tinker children at Aldour

Newspaper piece about the ‘Tinker School’

Letter from the head of Pitlochry High School about my mother

My father, Charles Riley

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To my dear friend Anne for all her work and friendship.

To Robert Dawson, for uncovering the plight of the Scottish Travellers in the nineteenth century through the 1895 report for the then Secretary of State for Scotland on ‘the Vagrants, Itinerants, Beggars and Inebriates of Scotland’.

To Jim Caird for providing A History, or Notes upon the Family of Caird, plus the Clan from Very Early Times by Rennie Alexander Caird (1915).

To The National Archives of Scotland for Educating of Scottish Tinkers and Vagrants.

To the A.K.Bell library for copies of the Aldour Tinker School log book and letters.

To Seamus Macphee for allowing me to ransack his collected papers on the Perth and Kinross housing experiment for Tinkers.

To the Orkney archives.

To Sheila Stewart MBE and to Donald, John, George and Alistair for their sharing of family stories and filling blanks in the narrative.

To Belle Stewart BEM.

To Mary Mackay for her information on Irish Pavee (Irish Travellers).

To Mary Hendry for allowing me access to her prized collection of Andrew McCormack’s Gypsy and Tinkler books.

To David Cowan for his expert advice on standing stones and to Colin Mayall who helped me understand a little of the Pictish and Roman history.

To Macainsh Brown for transporting me back in time to the day of a powerful battle over illicit stills.

When I was researching and compiling this book a ‘sea of souls’ closed ranks to help me make sense of a huge quantity of material. I want to shout out their names from a high point, but they wish for no recognition. You know who you are, so from my heart – a million thanks.

THE INSPIRATION

‘There can be no greater enjoyment to the inquisitive mind than to find light where there was till then darkness.’

From William Forbes Skene, The Highlanders of Scotland

It was early 1982 and there we were: him at death’s door and me crying my eyes out over the linen-sheeted bed, watching his life ebbing away. Gripped by the sheer helplessness of knowing that at any moment his sun would dip for the final time, I made him a silent promise: to discover as much information about the Scottish Travellers as it was possible to find, and to write a book, a simple, easy-to-read book.

Yet, walking away from the hospital as the linen sheet was being pulled across his face I knew there was no way I could write as much as a goodbye note, let alone a book, in memory of that good man, my father, Charles Riley. I had no proper education apart from the usual basics. Our family were travellers of the road, and we would leave school in April, re-entering the classroom in October. Our ways were travelling and had always been so.

Twenty years went by and my own family had flown their nests. Totally convinced that writing a book was far beyond my abilities, I’d decided instead to go where I could feel the breath of my ancestors and walk in their hardy footsteps, traversing Scotland’s remote paths and climbing her formidable mountains. I found peace and happiness in the sky above and the rock beneath, and I wished nothing better for the future.

But life is an unpredictable mistress, guided by blind circumstance. My father had a favourite saying: ‘What’s before you will not go by you’. He wasn’t a religious man, and he allowed fate to guide him. I believe that is exactly how this book has come about, because in the summer of 2000 fate began to map out a new path for me.

I had just traversed across Buachaille Etive Mor and the neighbouring peaks of Glen Coe, the mountains glowing red and brown with autumn hues. It had been one of those days that all hill-walkers and mountaineers experience at some time: next to perfect, just enough warmth of sunshine on the climb and the bluest clarity all round on the summit where the eye can see for miles.

As I trudged back to the car park I was suddenly aware of something missing; there was a haunting silence. Why was there no busking piper? Standing on a narrow strip of tarmac in Macdonald’s glen I strained my ears for that familiar sound, a sound that had always been part of me and my past. Where was the piper resplendent in full Highland regalia – the towering giant, Wullie MacPhee, or John Macdonald, the auld weaver, or those stirring masters of the bagpipe, the Stewart boys?

The tourists who flocked to the Pass of Glencoe would eagerly take photographs of the Scottish piper, surrounded by the glens and mountains of their forebears, the heartland of the Diaspora, to display proudly back home. To many this moment was the highlight of their Scottish tour. At Edinburgh Castle pipers resplendent in their tartan kilts made excellent subjects for a camera lens, but they were nothing in comparison to a lone piper, his face brooding on the past, with the haunting shape of the Aonach Eagath ridge on his right and the Lost Valley on his left, the deep notes stirring the ghosts of Macdonalds’ children massacred centuries ago by those who ruled Scotland.

Standing in the vacant circle of silence, legs weary with the day’s climbing, my heart ached. I was mourning the loss of those giants of Traveller culture who piped through thunderstorms and fierce gales. They did it because they needed their summer busking money; without it they’d see a lean winter, but it was more than that, much more. Piping at the Pass was a way of honouring those Macdonald clansmen.

My career as a writer was seeded that day. Somewhere deep inside a quiet voice was urging me to write about our kind, those who were the pipers of the pass, to write about our lives, our paths and campsites.

I have told the story of my first steps in writing in my earlier books, the Jessie’s Journey trilogy. I decided my lack of English grammar would not stop me, and with that in mind, when I began to write, I didn’t write to be read, I wrote to be heard! This approach proved highly successful, and I now have five published books to my credit. My journey as a writer began ten years ago. Since then I’ve met many people and have never stopped sharing my own story and the tales of my culture with an eager readership.

I’d carved my niche and was ready to carry on writing my books about life on the road. Then a totally unexpected thing happened. I was signing my books at a book festival in the north of Scotland. An elderly lady approached, grabbed my arm and spoke to me seriously. ‘I’m a keen fan of your books and those by other wandering folk who’ve penned their personal stories. I like nothing better than to sit and read them with a cup of tea. I’m an old woman now, but I was raised on tales about all you wanderers of the road. My granny and her granny before her swore by the skills of the tinsmiths who went from place to place. But as a matter of fact we didn’t know them as “travellers”, they were our Tinker folk who mended pots and pans. There’s an untold history about all these people, your people. Why don’t you find it and write it down? Now that you’re a popular writer, why don’t you tell Scotland what the schools ignore, the complete history of the Tinker folk? Forget kings and queens, concentrate on that!’

I was totally dumbstruck. Was this my wake-up call, fate guiding my pen? Perhaps this elderly lady had the uncanny power to see into my mind, or was my father using her as a gentle reminder that I’d made a deathbed promise?

I was worried. Insurmountable obstacles troubled me. How was it possible to write a book about a culture that was always on the move? About a people steeped in secrecy? Just because someone wants to capture it in book form, how can a hidden history suddenly be uncovered? Previously written material about my culture was preserved in the realms of academia, and dealt over and over again with a small number of characters who didn’t even seem real to me. Where could I find a thread to guide me, to help me start my journey? Where would I find my sources?

There’s an old saying, ‘If you look hard enough and search long enough you’ll find what you’ve lost.’ I began an in-depth reading of Scottish clan history. Throughout my life I’d been told tales, some of them dating back to biblical times, and all supposedly fictitious, about lost tribes of Israel. There were later stories about Irish kings with tinsmiths in the midst of their courts, of the break-up of the Jacobite clans and much more. I linked these to myths and legends about ancient smiths and the Roman occupation of Britain. In national and local archives I searched out government documents dealing with tinkers, vagrants and itinerants. Other clues were to be found in stories of tribal peoples found in the Bible, and finally, and most importantly, in the tales of the Travellers themselves, keepers and carriers of my culture. I’d found my sources.

Yet even before I began, another problem presented itself. What should I call my Travellers? In the past they were identified in many forms: as the olive-skinned gypsy with an eye for romance; the tinker/tynker/tinkler with his hammer and nail; the chapmen who not only sold their wares from village to village but brought story and song along with them; the vagabond tramp with nowhere but heather and glen to lay his head; the strolling minstrel and guising actor; bargee sailors of canal and river; the circus clown with painted tears; Romany folki; didiki; barrow boys, whispering horsemen and the gift-of-the-gab hawker. There are countless more names and identities. Even in histories and academic literature authors go from using the words Gypsy to Tinker while describing the same groups. Yet though the variations are innumerable we are really all people from the same seed. From this point on, when referring to historical accounts of my wandering people, I will revert from the name Traveller to that of Tinker, since this is the name that is used in most early books and documents.

This book is by no means an exact account of what really happened in history, but for those still travelling and those long settled it may help to point them in the right direction for a deeper search. I lighten the historical facts with stories of life on the road. As with my previous books, part of this history unfolds as we journey across the countryside, sharing myths, legends and customs as we travel on.

1

THE LOCHGILPHEAD TINKER

My maiden name was Jessie Riley. I was born in 1948, fifth daughter to Charlie Riley and Jeannie Power. Although described on census records as Tinkers, my parents and relations would be referred to as Gypsies in modern academic studies. Our mobile home was a neatly converted Bedford bus. I shared my travelling days with a sharp-witted father, petite fortune-telling mother and seven sisters; our lives were not blessed with brothers. Our only other companion was a stubby-legged fox terrier affectionately referred to as Tiny, the stud!

Apart from putting food in our bellies it was my father’s job to drive us wherever he felt the urge to go. He guided us through childhood and in my case made me conscious of our great culture and heritage. We shared our wanderings with wily foxes, rutting stags and snared rabbits, lived on mashed tatties, Scotch broth, soda scones and game. In winter, for a hundred days, our education was in the hands of the State. To me this was a prison, but we were taught to read, write and count. In summer our education came from my father. His motto was ‘respect the earth and commonsense’, and it has moulded me into the writer I am today. He enrolled me into his ‘organic university’, without a lectern or a single red brick.

I was the proverbial question-everything child. I also had my ears open for every scrap of old knowledge or tale of the past. Once a wise old Tinsmith made my head reel with a historical account so vivid and yet so fantastic I hardly dared share it with anyone else until this day. I didn’t believe his story at the time and for most of my life gave little thought to it. It’s true he was a fantastic storyteller; but what I heard that day, I decided, could be nothing more than a Tinker’s tale. Let me share it with you . . .

It was a balmy summer’s afternoon in the late fifties. I was skipping about amongst shale on a calm beach near Lochgilphead in finger-shored Argyllshire, Scotland’s most spectacular county. The Tinker man was working at his craft and making a colander for a minister’s wife. She, like the man of metal, was of the old ways. Throughout her lifetime she had ordered baskets, heather pot-scourers, besom brooms and washing pegs from the passing tinker folk.

He sat at the open tent door of his tiny one-man abode, a lean figure dressed in a baggy jacket with leather-patched elbows and trousers frayed at the bottom. He wore a grey waistcoat with slit pockets buttoned over a collarless shirt. From one pocket hung a chunky gate chain, attached to a silver watch. Apart from his tools, these were all his worldly goods of any value. At an angle on an almost hairless scalp he wore an old army cap sporting an array of fishing hooks round the crown. Intermittent puffs of greyish smoke came from a clay pipe with a yellowed stem; only ever leaving his lips to allow him to spit on the ground. With a short-handled hammer in his blackened hand, he clinked gently on a masterpiece of shiny tin.

He seemed ancient, steeped in wisdom. I can’t remember why, but I had a question burning within me that needed answering, and who better to ask.

‘Tinker man, will you stop hammering for a minute and tell me something?’

I stared into his crinkled eyes as I quizzed him further: ‘Where do we come from? And why is there always a fat boy who picks on me at school? And why are there people who stare at me with devil eyes? Why?’

‘Folk don’t like us, lassie, for this reason. Long, long ago, Romies brought us away from our tents in the desert. They stuck rings in our ears, chained us up, and made slaves o’ us; turned us into human tools. Some of us ended up in Scotland. But don’t call me a Tinker – I’m a Caird.’

‘What are Romies and Cairds?’

He didn’t answer, just pushed me to one side and chucked a log onto the embers of his near-dead fire. Then he continued. ‘It’s ingrained in folk to hate us, and they don’t even know why. But I do. My father, his father and all their fathers before them knew.’

A spiral of blue smoke curled around my shoulders and with the help of a brisk wind blew into my eyes and up my nose. I twisted my head to one side and then the other in a fit of coughing.

He pulled on my sleeve and pointed at a log seat beside him. I sat at his command and got ready to listen to the wisdom of an elder of the Tinsmith trade. He spoke again.

‘Greedy conquerors, with a hunger to control the entire known world, that’s who the Romies were. The true folk o’ this land of Scotland were called Picts, and they tried hard to keep the Romies away from their forts and weem tunnels, but were beaten in battle by the very swords our people had forged. Aye, nobody made the double-edgers like the Caird blacksmiths. Somewhere in that struggle of olden times you’ll find the reasons why we’ll never be accepted.’

He rubbed his large nose with the back of a hand and said, ‘Get away with you now and leave me in peace.’

My mind was racing with a million questions, but as I turned on my heel to run off he tugged my sleeve again and said, ‘Wait a minute lassie before you slope off.’ I sat down once more on my seat. He laid his hammer and the piece of tin down on the ring of burnt grass at the fire’s edge, and showed me his brown hands. ‘See the colour o’ this skin? These hands are not from this land. African deserts is where you’ll see the likes of these. There are other tribes of our kind came out of India over fifteen hundred years ago. They even come here to this country but their tongue is different from ours.’ He picked up his hammer again and added, ‘Keep all this quiet, my girl. No one likes a brainy Tinker.’

He muttered something in our cant language about the ‘manging tongue’ of the Gaul, and added, ‘There never was such a tongue among us folks, our language was Hebrew! Where do you think the name Hebridean Isles comes from?’ I shrugged my shoulders; I was trapped in a maze with no way out. ‘It comes from our people. We hear the call of the desert and are off to the wild places with our tents.’

My head was spinning, but it seemed to me this old man was one of the best storytellers who ever lived. He could take a tree’s shadow and convince his listeners that there was a giant hiding behind the trunk. And at that moment I thought he was spinning me the tallest tale imaginable.

At the risk of trying his patience too far, I asked him why I should stay silent on the matter we were talking about. ‘You’re kidding me and making it all up. Anyway if it’s true what you said, then why should I not shout it from the rooftops?’

‘Because, lassie, folk only believe what they read in books. We keep everything in our heads, and always have. But because there’s no books written about our olden days, when people hear our stories they call us liars and fools.’

My history master lowered his eyes and stared into the depths of the fire. I’ll never forget the look on his deeply lined face as he touched my hand and slowly nodded his head. Yes, what he was saying was the truth – perhaps not my truth that day when I heard it, but certainly he really believed it. It would be another forty years before I discovered for myself that this history had been recorded, and read the name of the Caird in a printed book.

I stood up and stamped my foot on the ground. A million particles of ash rose into the air and eddied back down to earth. Waving my arms I cried out, ‘A Traveller should find the truth about this and write a book about it. They’ll believe it then!’

Fixing me with his eye, he hissed, ‘The worst thing that ever happened to our kinchin was putting them to schools!’ He laid down his hammer again. An incoming tide was creeping nearer to our fire. His bones cracked as he rose to his feet and recited a poem, which I later learned was written by the Scottish poet Andrew Lang.

‘Ye wanderers that were my sires,

Who read men’s fortunes in their hand,

Who voyaged with your smithy fires,

From waste to waste across the land,

Why did you leave for garth and town,

Your life by heath and river’s brink,

Why lay your Gypsy freedom down,

And doom your child to pen and ink?’

With this our conversation stopped dead. The old man closed his teeth around the pipe and said no more. It was as if he’d swallowed hot coals and and was robbed of the power of speech. Perhaps he thought he had already stepped over the line, sharing secrets long held, never uttered, especially to a blabbermouthed teenager. He waved a half-burnt stick at me, as if he was shooing a pup away.

A few minutes later I was breathlessly relating what I’d just heard to my father. Like me, he had a passion for the history of our people. He knew of the slave and Roman connection, but shook his head at the void of time that separated us from those days. He reminded me that King Edward Longshanks burnt every Scottish library he could lay his torch to after his fight with Wallace in the wars between England and Scotland. Cromwell the witch-hunter finished the job when he torched Catholic abbeys and their collections of books and manuscripts. If there were books mentioning Rome and its Scottish slaves then they would have been lost. Academics wouldn’t allow this version of history to be taught in schools. He also reminded me that many Travellers had long since given up their old ways and would take no pleasure hearing of an historical account making out that they were different from normal people.

‘There’s a fear among some of their own Traveller identity. It is woven into the tapestry of history, but the scattered threads of our story have been unpicked by years of persecution. Maybe one day when I am an old man and you have grown into a woman, changes will come.’

Because we shared a passion for history and respect for our Traveller identity, our father and daughter relationship was tested many times after this. We had serious arguments about whether he should write about his experiences. He had lived through hard times in his early years and I wanted him to tell the world about it, but he didn’t seem willing to do that.

Many years later when his travelling days were behind him, and old age had brought ill health and the usual wear and tear, he sprang a surprise on me. He opened a drawer in the small bureau by his fireside chair and took out a large notebook. Smiling from ear to ear, he said, ‘Well, Jess, I’ve started that book!’

I was at his side in an instant, but he slammed the drawer shut. ‘When it’s finished I’ll surprise you, Jess.’

Two years later he’d still not shared the writings in his notebook, and to be honest I didn’t think there was much of them to share. My mother said she thought he’d given up the idea. The opposite was the case. He’d scrapped his volumes of handwritten material and hired a typist to work on an autobiography with no holds barred.

He called the book The White Nigger, a shocking title, but one that described how he felt he had been treated all his life. Although my enthusiasm to read what he’d written was overwhelming I stayed out of his space and waited until he’d finished.

But there was an enemy creeping into his body; emphysema, like a nagging wife, dominated his every waking minute. To try to get relief he woke early, went over his handwritten notes, and then slept most of the rest of the day, getting up for a few hours to dictate the text of his book to the lady who typed for him.

Two different coloured inhalers which never left his side kept his airways clear, and without them he would have suffered a fatal seizure. To be honest it was touch and go whether he would finish his masterpiece, but he was no quitter. He remained adamant however that I shouldn’t read it until the time came when he thought it was ready for my eyes. I was sorely disappointed not to be able to read it, but he said it would look much better as a proper book with a nice cover, a personal signed copy from father to daughter.

One day he completed his task and sent the finished typescript to a renowned folklorist. An answer came by return: ‘I shall be happy to read The White Nigger over the festive period.’

I remember holding his feeble body and feeling the emotion and sense of achievement running through his weakened frame – at long last he’d written that book! He had climbed an unconquered mountain, touched a star – his life would now be worth something.

With the greatest sadness I have to write that, for reasons that remain unknown to me, the book was not referred to again by the renowned folklorist and was destined not to be published.

2

THE BEGINNING OF THE JOURNEY

Although I never forgot the revelations of the Lochgilphead Tinsmith, I found that searching for the origins of Travellers was an almost impossible task. It was like asking a palaeontologist to recreate the body of an ancient dinosaur of the largest size from a few bones, in minute detail!

I did come across a tale told by Spanish Gypsies about the beginnings of our kind.

Once upon a time when the first man and woman were moulded, the god of the earth breathed his perfection onto a handful of seeds. He planted the seeds in a small bag beneath the tree of knowledge. When the original couple, Adam and Eve, had disobeyed his command and eaten of the forbidden fruit, he turned them out of the Garden of Eden, blaming himself for allowing them the gift of free will.

The many gods scattered throughout the heavens laughed at the god of the earth and said, ‘It was a mistake to sprinkle the seeds with perfection when there is no such a thing.’

The serpent of the underworld, which existed to tempt all living creatures, thought differently. She knew of the bag of seeds, and thinking the earth god would try to populate his world once more, but on his second attempt remove free will from men and women, she stole the seeds and scattered them from a mountain top. From there the wind blew each seed to every corner of the world.

When the earth god discovered her cunning plan, he sent an angel to whisper to his seeds that they must never settle anywhere or else the serpent would find them. He further instructed the angel to tell them that they must set off on a journey, and when the time was right he would guide them home to the Garden of Eden. He blew breath through the angel into each seed, so that they would resemble his first children, Adam and Eve. He gave them many skills so that through the power of their hands they would survive. They were told they must not follow any king, accept any false book of instructions and that they should live by two laws: ‘Nothing in excess’ and ‘Know yourself’.

As we are on the subject of the mythical origins of Travellers, let me share another tale from ancient times. There are several versions of this story which mainly come from Eastern Europe.

The Fourth Nail and Ruth’s Seed

Jerusalem was in a terrible state! The Messiah was to be crucified, had been judged and sentenced. Pontius Pilate, the governor of the city, had delivered him to a prison cell to await his death the following day upon the rugged cross.

It was midday, and two of Pilate’s young soldiers were given a large sum of money to pay for four nails. They were to be forged by the hand of a Jew. Those were the orders, and the young recruits were to be back with the nails by curfew. The city was at boiling point, and after dark a roman soldier outside the security of his garrison walls would not have stood a chance.

Beneath their uniforms of thick leather and metal armour the sweating flesh of the two men overheated. With the additional burden of swords, shields and spears, they were fit to melt. As they stepped out into the streets of Jerusalem, a delicious aroma of rich wine wafted from one of the many inns along the way. They looked at each other, both thinking the same thing. We had better replenish our flagging energies before crossing town to the quarter where blacksmiths worked their forges. It was an easy decision to take: they would slink in and take a few pennies’ worth of wine.

Once they were inside and their weighty helmets and weaponry laid aside, one drink soon led to another, and then another. Lowly foot soldiers seldom had so much freedom, or so much money in their hands. In no time the amount of money they had been given was halved.

Only when they saw how little was left of the money did they come to their senses. Aware that their decision to waste on drink the money given for a specific purpose would lead to a nasty end on the cedarwood cross like other thieves and murderers, they rushed outside into the dusty streets. Where had the time gone? It was almost five, and the curfew bells rang at six!

It was not two disciplined soldiers of the mighty imperial army, but a couple of drink-sodden, dishevelled, angry individuals who stood in front of the big Jewish blacksmith with the hammer in his hand. When they ordered him to forge the nails and be quick about it, he asked for payment. When they offered only half the regular amount, he refused. They were in no mood to tolerate disobedience to the might of Rome from a subject Jew. After demands came threats. When, however, the frightened blacksmith asked why they wanted four large nails, the soldiers angrily retorted that they were to be used to crucify the prophet.

The smith laid down his hammer and refused to do the job. Defying furious soldiers with so much alcohol in them could only have one result. In a matter of moments the poor smith lay in a pool of blood and the soldiers pushed on. Three more times they were refused, first by a Samarian, then by a Carpathian, and then by another Jew. However often they asked, no hand would forge those nails. Soon each of the obstinate blacksmiths lay dead.

As the soldiers, now beginning to sober up, reached the city wall and found no more blacksmiths they began to panic. There was only one more chance. The Egyptians who lived outside the walls of Jerusalem had blacksmiths. As the curfew was fast approaching they broke with the usual protocol and went outside to find a blacksmith. The soldiers found a man called Cyrus working at his forge. He was a poor man with a pregnant wife to support and had never heard of the son of Joseph Bin Miriam. However there was a problem – Cyrus had no iron with which to cast the nails.

None, that is, apart from a precious gift he had received two nights ago from Seth, the Egyptian God of storms. In countless prayers he had asked for a blessed piece of heaven-rock, as the Egyptians called meteorites, from which to forge the fingers of Seth. Also known as the ‘Bia’, the fingers of Seth were a delicate set of tongs and were considered the greatest gift an Egyptian father of the blacksmith craft could give his first-born. The High Priest of the Egyptian religion would use the tongs to open the mouth of the dead person in a ceremony performed on the ‘mummy’ at a funeral. The ‘opening of the mouth’ enabled the soul to give the correct answers to the doorkeepers of the underworld and to gain admittance to the underworld. The blacksmith who was the keeper of such an instrument was held in great honour by the High Priest. Just two nights previously Cyrus’s prayers had been answered: a meteorite fell from the sky. Believing that the God of storm had indeed blessed his new-born child, he kept this heaven-rock made of precious metal out of sight, keeping it in a small casket beneath his forge.

As the soldiers grew angrier he lowered his head and apologised to them for having no iron or any other metal with which to make the nails. In blind panic they began to trash the man’s small workshop and soon found the casket with the blackish lump of metal inside. ‘Here,’ one said, thrusting it at the blacksmith, ‘use this.’

Cyrus had no choice: the soldiers had their swords in their hands. So taking the mysterious lump of planetary metal, he piled more charcoal into his brazier, use the bellows to create a fierce heat and forged three stout nails. Before he could finish the fourth, the first chime of the curfew bell rang within the city. Grabbing the three nails that were ready the men rushed off. What lies they were going to tell as an excuse for their lateness, was their business.

Cyrus’s heart was heavy. The heavenly metal Seth had sent him was now in the hands of the Romans, and was to be used to crucify a strange Jew! That night, as a full moon rose over Jerusalem, the worried blacksmith, tired and hungry, went home to the arms of Ruth, his lovely wife, a daughter of the ancient Hebrew tribe of Dan. Against her tribe’s laws and customs Ruth had married an Egyptian; just another curse to add to those already weighing on the shoulders of her tribespeople, who were now scattered far and wide through the world.

Many centuries ago the tribe of Dan was among the multitudes of other Hebrew slaves who left Egypt and followed Moses to the Promised Land. Half-way there, however, as their holy leader was on Mount Sinai receiving the Ten Commandments from God, the tribe of Dan melted down all their gold and formed a statue to the God Baal. He, the god of all earthly pleasures, offered them a way out of their miserable wanderings in the desert: a new world. When Moses discovered their blasphemous idolatry he sent them out of the Hebrew encampment. He said he was separating goats from the sheep. He kept the sheep who followed the true God and laid a curse on the goats to wander the world forever.

So, unaware of the cataclysmic event that was to take place at dawn the coming day, Ruth and her husband slept peacefully in each other’s arms. When they awoke the next morning there was a strange darkness, and it rained all day.

On the following day, before breakfast, the sound of an angry mob was to be heard outside the house of Cyrus and Ruth. The two soldiers who had broken the curfew and returned with only three nails, when they had been sent for four, were awaiting deportation to the island of barbarians, Britannia, as a punishment. Word had got out that they were helped by an Egyptian, who had forged the nails that crucified Christ.

Within minutes Ruth stood, tears streaming down her cheeks, as they dragged off her beloved husband, who she knew to be an innocent man, to be interviewed by the authorities. Next day she visited the governor. He’d let her husband go free if she would pay for their passage aboard a slave galley, along with those accursed soldiers, heading to Britannia. This she did willingly. Not long after, they set sail for a new life in a faraway land where their fate awaited them.

They disembarked at last on the shores of the north of Britannia, the land which in ages to come was to become Scotland. Although they were free people, because of Cyrus’s skills they were both put into chains on arrival. They worked as slaves in the fortified home of a Roman general: he as a forger of weapons, and she, after the birth of her baby son which took place soon after they landed, was employed as a hairdresser and hairbraider of Roman ladies.

Their son grew strong, into a handsome and pleasant-natured youth. His master became so fond of him he gave him his freedom. And there the story peters out, but it has a mysterious sequel.

The fourth nail, according to a tradition among European Romanies, was given into the care of Ruth by her husband Cyrus. When he died she asked the authorities for permission to allow her and her son to bury her husband in a special sacred place. Permission was granted. They lowered him into the ground along with a small, narrow box. His grave was ten feet deep and filled in with stone rather than earth. I was informed by those who told me the story that the place where he was buried remains a sacred site, and there is a chapel there. Nowhere else in Scotland, they say, stands its like. I tried to find out from my informants the exact location, but they refused to say, apart from indicating that it was somewhere near Edinburgh. They visited the place annually.

I found a very interesting story which might shed light on this mystery while scanning through Robert Chambers’ Domestic Annals of Scotland from the Reformation to the Rebellion. He writes: ‘While Egyptians [i.e. Gypsies] were looked upon as a proscribed race, and often the victims of indiscriminate severity, there was a man who believed that every one deserved mercy. This was Sir William Sinclair of Roslin Castle, Lord Justice-General under Queen Mary, and while riding home one day from Edinburgh, found a poor Egyptian about to be hanged on the gibbet at the Burgh-moor.

“Why are you hanging this fellow?” he asked the Sheriff.

“Sire, this is a Gypsy and as you know his very existence is an abomination against God.”’

Sinclair lied and said that the man was one of his stable hands and had nothing to do with Egyptians. Instantly the rope was removed from his neck and he was set free.

He wasted no time in warning the young Gypsy that he and his people were in danger, and to avoid capture they should come and winter around the stanks [marshes] of the castle were he would give them sanctuary. That winter was the severest it had been for many a year, the poor Gypsies were freezing to death in their thin canvas tents, and if Sir William hadn’t offered them shelter in two towers of his castle they surely would have perished. From that kind act they named the towers ‘Robin Hood and Little John’, and every year, to honour their kindly saviour, they acted a play of the same name.

It may be more than a coincidence that close by Roslin Castle is the famous Rosslyn Chapel, where reputedly the Holy Grail is concealed.

At Roslin there’s another Roman connection. I’m told that to be found there is the grave of a great outlaw called Salamantes, who at every opportunity fought and harassed the occupying Romans. It’s believed that he hid slaves who were considered too old to work, or ones who became ill or injured, before their masters ended their lives. Had Salamantes himself been a slave from Egypt, perhaps going on to be one of the forefathers of a strong Highland clan?

3

THE GREENS

None of us knew why generations of Travellers chose the same camping grounds, but year after year familiar faces and stories followed one another, like dog nose on cat tail, to the same spots. Those were our private holiday places, and every year my people returned to relive the joyful traditions within our own society; to speak our language, share stories and sing songs. There were many places – coastal inlets with caverns, tussocky moorlands, ancient areas with standing stones and burial mounds that belonged to the once mighty ancestors of Scottish people called the Picts. I can only guess that these were places that no man of authority could put his stamp on. But perhaps there were deeper reasons behind the choice of such peaceful campsites.

These common camping places, along with many others, were known simply as ‘the greens’. When it was time to uproot and take to the road after a long cold winter, my father could be heard repeating his itinerary of ‘greens’, our safe havens where law could not touch us and no one would trouble our peaceful existence.

For this part of the journey to enlightenment I shall concentrate on the campsites of Perthshire, especially the ones that no longer exist. Some of them now lie under widened roads, housing schemes and supermarkets.

Beginning around the 1930s, Perthshire was flourishing as an agricultural area. Farmers and Travellers needed each other. Our favourite summer greens were ones prepared for us by eager Perthshire fruit growers seeking a hardy workforce to gather berries, strawberries and peas. For the travellers to make a decent enough income to see them through the coming winter, this was an important part of their year. Hard-earned harvest money helped pay the winter rent, bought the ‘tug’ for hawking and, for the children, paid for our school uniforms.

It was also the final chance to live as a complete society again. As we gathered at the days end around a welcome camp-fire, we sang ballads and shared our tales. For a few weeks of the year the old tribes of Scotland lived again! Later in the year we converged on the fields to gather up the nation’s potatoes. Sadly, all these jobs are no longer viable for Travellers and Scotland’s agricultural work is now mainly undertaken by Eastern Europeans.

Life came and went on the greens: in one tent an old person lay flat out on a straw mattress, taking his final breath; in another, a new life began, a baby punching the air for the first time. Elsewhere on the green, deals were made. Hands slapped to seal the deal for a new lorry, a good hound and, on the rare occasion, a good woman!

On the greens of Blairgowrie at berry-picking time, folklore revivalists in the mid-fifties discovered the wealth of our songs and ballads, the music of the pipes and stories that seemed to flow from the Travelling folk like streams of gold. They came from all over the world to record our music, riddles and songs, which they then introduced to a waiting world. The famous travelling family, the Stewarts of Blair – mother Belle and husband Alex with his bagpipes, daughters Sheila and Cathy along with songbirds Jeannie Robertson and Lizzie Higgins – had no idea what heights of fame the folklorists would elevate them to. Matriarch Belle, for her contribution to the world of traditional music, was awarded the BEM; her daughter Sheila, the sole survivor of the Stewarts of Blair, who now carries the wealth of traditions on her own, was given an MBE.

Jeannie Robertson’s famous nephew, the late Stanley Robertson, was an expert on the Tinker folk of the north east, a brilliant balladeer, storyteller and acclaimed author. Before his death in 2008 he was made a Fellow of Aberdeen University.

All the folklorists were held in high regard by the travelling folk, especially Hamish Henderson, affectionately referred to as ‘Him wi’ the box’, the box being his recording equipment (battery-powered, of course). I remember late one evening, when he arrived at our campsite to set up his ‘box’, he asked if anyone had a stool to sit it on. My father dutifully pointed at my own three-legged contraption, which he had made for me to sit on after I had broken my leg, but I point-blank refused to give it to Hamish because I thought he would sit on it. If he had done, with the size of his behind, the stool would have ended in bits on the fire. Everybody burst out laughing when Hamish said he only wanted it to put his box on.

Other familiar faces at our campsites were the collectors of folksong and folklore, Ewan McColl and American Peggy Seeger who, like Hamish, sat around the campfire at night, recording the musicians and songsters. Daddy was impressed by the visiting collectors, and remembered one or two of them in later years, but thought most were on the make. He thought they were stealing the old songs, and for this reason refused at the time to approach them and let them record his traditional knowledge. In this he wasn’t alone among Travellers. It was considered taboo to let outsiders in. No one should know our words, songs or riddles apart from our own kind.

Personally, I am glad this work of collection continued over the years. Who would know about us in the future, if the recordings hadn’t been made and kept safe in Edinburgh University’s School of Scottish studies? But in hindsight I feel the collectors only got the tip of the iceberg. Waiting in the wings were many more talented Travellers who would have liked to be heard, but when the folklorists ended their studies, they stepped back into the shadows and gave up on the dream of showing off their abilities.

During tattie-picking time, other greens near Crieff in Perthshire saw the gathering of many travelling folk. Crieff is set in a great stretch of fertile land which, through the famous Perthshire tattie, brought wealth aplenty to scores of farmers, who all provided greens during the season for large numbers of ‘tattie howkers’. Duncan Williamson, who once told me he thought his people were descended all the way from the Picts, met his pretty young wife-to-be, Linda, at one of these. She was there in her capacity as a field-worker in the area of folklore, and she went on to introduce Duncan as Scotland’s master storyteller to the world.

Another Traveller writer, the late Betsy White, who gave the world those wonderful classic books Yellow on the Broom and Red Rowans and Wild Honey, spent many summers on her favourite greens and later shared her experience with a world of eager readers. During berry-picking time our family and hers camped side by side on a green called Marshall’s Field, a mile from a quaint little town called Alyth. In those early years neither of us had the slightest notion that one day we would both write extensively about our cultural journeys on the roads.

4

MANSION ON WHEELS

We travelled the length and breadth of Britain in our bus-home, and I gathered every memory like a magpie collecting coloured baubles. In our mobile dwelling a twelve-inch wide woollen carpet, stretching from underneath the driver’s seat to our parents’ boudoir at the rear kept our feet warm. A cupboard for pots, pans and dishes was bolted to the floor, the luggage racks above our heads accommodated our undies, there was a table where we shared our family meals and a wee Queenie stove for heating and for cooking during the winter. In summer a campfire did the same job.

When springtime approached, my excitement knew no bounds. The road called and there was nothing to hold us back. I think there could be no creature in the entire world more ecstatic than me at leaving our winter campsite behind. I was acutely aware that all across the land other Travellers were stirring from their hibernation, eager to smell the reek from the camp fire and to taste fresh air once more. The winter of hard frost and snow with its burden of flu and coughs was gone. Vivid memories of the big bully boy of the classroom would drift away like the smoke of town chimneys as we headed for the countryside.

The schools officially closed in July, but Travellers were able to leave in April before the settled kids. To do this we needed a certificate authorising our release, and once we had got this there was no holding us back. Honestly, it was like getting out of prison. Until that vital certificate allowing me and my siblings to leave in springtime was secured in our mother’s brown leather handbag, I didn’t sleep soundly. If she had lost or misplaced it she’d have incurred the wrath of us all. The laws relating to Travellers’ education were tight, and later in this book we shall discover why.

Before we could set off, however, that old blue Bedford bus had to be given a service. Sometimes a coating of rust had curled around every nut and bolt, but this didn’t matter because my father could fix anything. During the war he had been trained as a mechanical engineer, and now he cared affectionately and skilfully for his mobile home. The bus had to be completely mechanically sound – Scotland’s country roads could throw unforeseen potholes in our way, or the police in certain areas who had an intolerant attitude to Travellers would keep us on the move. So he’d don a baggy pair of oily overalls and live in them until the repairs were complete and the engine whipped into prime condition.

We were known among the Travelling community as Charlie and Jeannie’s family of frocks. Our paternal Granny had another name for us – sardines on wheels. An old auntie called us premenstrual succubuses! My father was quite vocal about how Mother Nature had cheated him by never producing a male child for the family, but when we were left to our own devices we females could stack tons of corn, plant fields of potatoes, gather mountains of red fruit, clear acres of brock wool, dig deep ditches and work alongside the strongest men, equalling their strength. And we had brains too!

Our winter green for most of my teenage years was Lennie’s Yard, a redundant pottery built in red brick in the Gallatown, a district in Kirkcaldy famous for coal mines. Mr Andrews, who lived next to the yard, was a coal merchant who lived in a spacious Edwardian house next door. Many a day, over his old green gate, we shared a crack.

When everything was ready and my father revved up the engine I would stand by his shoulder behind the driver’s seat like Queen Boadicea, eyes scanning the horizon. Mr Andrew always positioned himself by the green gate and called out to me, ‘Mind, now, come home with plenty stories for me!’

Through the open window of the door I’d answer, ‘Do you want fairy or kelpy ones?’

‘Just keep all your adventures stored up in your head and we’ll share them when you come back.’

In my eagerness to see the back of our settled existence I would lean out the door with the wind in my hair. My mother would forcibly drag me back inside and shut the window tight, saying, ‘I’m in two minds about renaming you Mindy’s Monkey!’

Mindy was a Traveller from Aberdeen way. She used to stand up on her cart when her horse tackled a bend and shout out, ‘Gaun tae yer richt-haun side, cuddy, an mind an no wallop yon tree tae yer left!’ She was famous among Travellers for her companion of over thirty years – a wide-eyed monkey who, it was believed, knew every word of the Doric cant language. One day the horse got spooked by a noise from the undergrowth at the side of the road and began to gallop blindly out of control. Trying to stop the animal, Mindy grabbed the first thing to hand, which was her beloved pet monkey, and threw it at the horse. It fell into the road and hurt its leg. She swore blind that after that it refused to sit near her or eat from her hand. She said it was in the huff, and after its limp disappeared it ran away and she never saw it again. Within six months she died of a broken heart. Sadly, as a monkey is believed by Travellers to be a bad omen, not many other Travellers would have anything to do with her.

When we drove out of Fife with an east wind to our back, our usual route was to Perth, via Thornton, Glenrothes and on through ancient Falkland with its fairytale castle. Many kings and queens stayed in this ancient palace, but I want to mention King James V in particular, because of an incident that involved him and one of the first mentions in historical sources of the elusive Scottish Tinker.

King James was basically a decent kind of man and often wondered about his peasants and what their lives were really like. To find out he would sometimes disguise himself as a poor man, putting on the blue cloak worn by a beggar-man, or Gaberlunzie, as they were called. According to this story, which as far as I know is true, one day when he was in disguise he met a band of Tinkers. Unaware that he was of royal blood, they invited him back to their home, which was a cave near Wemyss in Fife. They had a party with singing, dancing and drinking. Being a jolly lad, His Majesty decided to join in, and soon became intoxicated with the drink. Inevitably a fight broke out. Jimmy found himself in the midst of the Tinkers’ brawl. Though born with a silver spoon in his mouth, he was outclassed in the art of bone-rattling, and thought he was going to be severely injured. His shouts and screams in his normal accent made it immediately apparent to the Tinkers that he wasn’t one of them. If this stranger wasn’t a true blue Tinker then he must surely be a spy.

Unsure whether they should kill him for his treachery or not, they decided to dump all their bundles on his back and use him like a donkey to carry them along the road. After several miles his legs buckled, so they left him lying exhausted by the roadside.

Back home in Falkland Castle, relieved to have escaped with his life, the king put his blue Gaberlunzie cloak away in a cupboard and never ventured out in disguise again. Despite, or perhaps because of, his experience, James V was generally well-disposed to Tinkers and Gypsies and they were not persecuted during his reign. However if the Wemyss tinkers had realised how his grandson, James VI, would treat them, they should have tried him for spying and stretched his bonny white neck when they had the opportunity.

James VI, who also had a boiling hatred against witches and caused many harmless wise women to be burned at the stake, loathed Gypsies and set out to exterminate them. Even before he came to the throne the authorities had issued a proclamation that Gypsies had to be treated like thieves and driven out of the country. This proclamation of 1573 stated that all Gypsies were ‘to be scurgit throughout the toun or parrochyn; and swa to be impresonit and scurgit fra parrochyn to parrochyn quhill thay be utterlie removit furth of this realme.’

When James came to the throne of England he wasted no time in passing further acts against Gypsies, or Egiptians as he called them, until just being a Gypsy or Tinker became a crime to be punished by death. His act of 1609 was passed: