Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

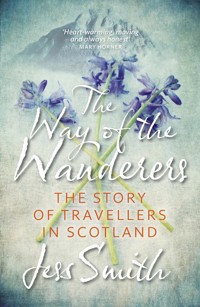

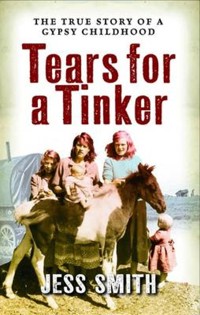

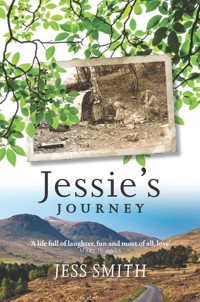

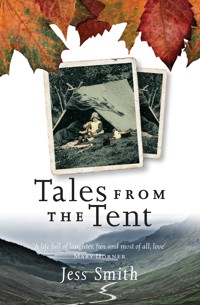

Tales from the Tent continues Jess Smith's story from the first book in the series, Jessie's Journey. Jess has left school, and after a miserable spell working in a paper-mill, she abandons the settled life and takes to the roads once more. The old bus has gone, to be replaced by a caravan and campsites. Times are changing, and it is becoming harder and harder for travellers to make a living by doing the rounds of seasonal jobs like the berry-picking. Conscious that the old way of life was disappearing before her eyes, Jess stored up as much as she could gather from the rich folklore of the travellers' world. Now she retells some of the many stories and songs she heard by the campfire or at the tent's mouth. Interwoven with these tales is the story of Jess and her life on the road - her first loves, her friendships, her days at the hawking and berry-picking, the exploits of her lovable but infuriating family, the unforgettable characters she meets.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 412

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TALES FROM THE TENT

JESS SMITH

was raised in a large family of Scottish travellers. This is the second book in her bestselling autobiographical trilogy. Her story begins with Jessie’s Journey: Autobiography of a Traveller Girl and concludes with Tears for a Tinker: Jessie’s Journey Concludes. She has also written a novel, Bruar’s Rest. As a traditional storyteller, she is in great demand for live performances throughout Scotland.

This eBook edition first published in 2012 First published in 2003 by Mercat Press Ltd Reprinted in 2003 and 2005 New edition published 2008 and reprinted 2012 by

Birlinn Limited West Newington House 10 Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Jess Smith 2003, 2008

The moral right of Jess Smith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-179-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

1 BACK ON THE GREEN

2 A CONVERSATION WITH WULLIE

3 A KINDRED SPIRIT

4 THE SEVERED LINE

5 THE TOMMY STEALERS

6 SANDY’S KILT

7 HARRY’S DOGS

8 THE GHOSTS OF KIRRIEMUIR

9 THE BANASHEN

10 PORTSOY PETER

11 FAIR EXCHANGE

12 THE BLACK PEARL

13 JEANNIE GORDON

14 THE BORDER GYPSIES

15 THE LAST WOLF

16 DAVIE BOY AND THE DEVIL

17 WINTER IN MANCHESTER

18 KING RUAN AND THE WITCH

19 HELENA’S STORY

20 MANCHESTER HOGMANAY

21 THE LETTER

22 BACK ON THE ROAD

23 THE KELPIE

24 HEADING NORTH

25 WULL’S LAST DIG

26 TRUE ROMANCE

27 ROSY’S BABY

28 A WARM NIGHT

29 SUPERNATURAL APPARITIONS

30 RINGLE EE

31 BLAIRGOWRIE

32 DEAD MAN’S FINGERS

33 FORGET US NOT

34 CRIEFF, THE FINAL FRONTIER

35 FOR THE LOVE OF RACHEL

36 THE OLD TREE BY THE BURN

37 THE END OF TRAVELLING DAYS

38 BRIDGET AND THE SEVEN FAIRIES

39 THE PROMISE KEPT

GLOSSARY OF UNFAMILIAR WORDS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Jessie’s father aged 15 with his boyhood friend, Wullie Donaldson

Jessie’s mother and father in 1942 (Pitlochry)

Jessie’s mother holding Babsy (Aberfeldy)

Jessie and her sister Renie

Jessie aged 14 with her mother, Jeannie, in Kirkcaldy

Jessie aged 14 with her father, Charlie, in Kirkcaldy

Jessie’s mother fooling around in Lennie’s Yard, Kirkcaldy

Jessie’s sister, Janey, in front of the bus

Sandy Stewart, the ‘Cock o’ the North’

Tiny the dog

Jessie and Davey on their wedding day in Perth, Hogmanay 1966

Jessie with her daughter, Barbara

Jessie’s children—Barbara, Stephen and Johnnie

Jessie with Johnnie and Stephen in 1983

Jessie with two of her sisters, Charlotte and Janey, and her mother

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There is a countless army who inspired, prodded, encouraged, laughed and cried with me whilst I was writing this book—many thanks for staying the course.

Dave the rock; Daddy and Mammy—never far away; Bonnie, Rosie, Rebecca, Meghan, Nicole, Jason; The Golden Girls; wee pal—cousin Anna; Janet Keet Black; Mamie for Keith’s poem; David Cowan; Glen neighbours; David Campbell the book man; Portsoy Peter (deceased).

A special thanks to Robert Dawson (my radgy gadgie); John Beaton; Catherine; Tom and Seán.

And a great big thanks to Michael G Kidd who wrote Where do I Belong? especially for me.

I am eternally grateful to the Scottish Arts Council, who through a fine grant allowed me the freedom to research further than I could otherwise have done.

I dedicate this book to Mac, of the old tattered journal

INTRODUCTION

Those of you who came with me on ‘Jessie’s Journey,’ when I told you about my life in our blue Bedford bus with Mammy, Daddy, seven sisters and Tiny, the wee fox terrier that could run rings round rats, will have an idea where we are going. To those who did not, then let me take you through the Scottish travellers’ life, a life of folklore, murder and mystery. Humour jumps on board too, folks!

Will you believe my tales? Perhaps aye, or maybe not. For what is fact and fiction in life when a falling snowflake can lead a young mother to trek upon a treacherous mountain in a blizzard perilously putting her two little boys in danger?

Would you like to hear of the threesome who dared to bury a Royal Duke in the wee coastal graveyard filled to capacity with tramps, vagabonds and tinkers? More to the point—was there room for him?

Those hounds of Harry’s, were they really dead? Did he survive because it wasn’t his time?

Deep beneath gorse bush and thistle, were those the fingers of a dead man? Or something even more sinister?

She killed her daughter! Didn’t she?

Well now, are you with me? Are you coming, reader, into my world, the travellers’ world, where children learn about Bonnie Princess Charlotte, and her evil quest to unite the clans? Think you can handle that? More to the point, will historians of Jacobitism accept it?

What a strange night old lovelorn Peter had when the mistletoe seller came a-calling...

Do you know there are creatures of the night that come within a moor wind? I hope you never have the misfortune to meet one! Perhaps a wee early warning never to unlawfully enter a place of the dead might help.

In Jessie’s Journey I told you of life in the bus. What I failed to divulge was, as death claimed night, that there sometimes came the ‘Tall Man’. Why?

I bet you’d love to hear Mac’s story. I can say with hand on heart you’ll never hear of another such start to a new life.

Why was Wullie Two so called? Laugh with me on this one, folks.

I have many, many tales and stories to share with you. Get the cup, boil a kettle, comfort the bones—oh, and don’t forget to lock the doors, because you never know, now, do you?

So, reader, are you coming with me on the road?

You are!

Great!

Who needs sanity anyway?

1

BACK ON THE GREEN

My bus home of ten previous summers was gone and everyone told me to stop greeting about its demise and get on with life. Sister Shirley reminded me daily that I was fifteen years old, with a whole life spread out before me. A world of wonder waiting to be explored, so get on with it.

But how could I? The neat bedroom she prepared for me with girlie curtains and bedspread to match stank of scaldy (settled) life and made me puke. I wished I was a road tramp with skin as brown as toads, eating out of deerskin lunzies and laying my filthy body down to sleep behind bumpy-stoned dykes, with a star-encrusted heaven as my roof. But a fifteen-year-old female wouldn’t last long. On the other hand I knew survival wasn’t impossible, not with the knowledge I’d accumulated on the road. We travellers are born survivors.

Shirley was kindness itself and tried her best to make me feel at home. So I bit my lip and said nothing about my true feelings.

The women at Fettykil Paper Mill in neighbouring Leslie, where Carl—Shirley’s then husband—found me a job, mothered the life from me. They recognised how unhappy I was. One of them called Stella was from travelling stock and she said she knew how I felt. At break there would be a fairy cake or half a Mars Bar and sometimes a wee drink of ginger (lemonade) propped against the paper-bag-holer machine I used. I knew it was Stella who left those treats because once I had told her how my Mammy did things like that in the bus. Whenever the old tonsillitis left me with a vile taste in my mouth she’d put sweets and tit-bits under my pillow or in my sock, anywhere I’d perk up on finding them.

Still, all the kindness in the wide world failed to remove my misery, and one day round about three on a Friday afternoon I collapsed at the paper-bag-holer machine. Not before plunging its giant needle straight through the index finger of my right hand, may I add. The factory doctor asked me if a period was the reason. Embarrassment turned me pure red in the face and silent. So he diagnosed period pains, even though it wasn’t anything to do with that. The nurse was a wee bit more concerned and asked if there was a problem. I don’t know if it was her gentle voice or the way she tilted her head as she bandaged that throbbing bleeding finger, but it opened the flood gates and I told her of my yearning to be home on the road with my own folks. ‘Lassie,’ she whispered, ‘away you go, pack your bits and pieces, and whatever you do don’t come back here on Monday.’ If I’d been offered a free dip at the contents of Fort Knox I’d not have been happier than when I left the high-walled paper mill as soon as I did.

I hugged Stella with tears of unbridled joy. She laughed and said, ‘My God, girl, you’d think ye were gittin oot o’ the stardy.’

‘I feel like I’ve been in one,’ I told her.

Shirley wasn’t too pleased when she heard I’d had it with the scaldy life. In fact she was mortified, but what else could I do? What choice did I have? None.

Within three days Daddy and Mammy came over to Glenrothes and removed me, wee brown leather suitcase and all. I can’t say I wasn’t sorry to leave Shirley, because all through my young life she was the heart of the bus, she was a fire when there was no coal in Wee Reekie, and I knew we’d miss each other. She was now a scaldy; her days of travelling had ended, Scotland’s roads were a wee bit quieter from then on.

Shirley may have left the road but the road never left her, and for starters here is a wee poem by her to give the coming chapters a bitty atmosphere.

The Berries

We a’ went tae the berry picking,

Aye, when we were young,

Wi’ oor luggies, hooks, strings and pails,

Boy, did we have fun.

We went in the summer, when the berries were ripe

And the sun was high in the sky,

Wi’ oor sloppy joes, jeans and boppers sae white,

A bottle o’ juice an a pie.

We met lots o’ new friends and shook lots o’ hands

And greeted the auld weel kent set.

Sticky juice o’ the berries wis stuck roond oor mooths,

It’s a sight I’ll never forget.

We sookit the big yins, then made oorselves sick,

And mother wis fair black-affronted.

We turned a shade green, were in bed for a week,

A doctor wis a’ that we wanted.

We grafted an blethered, rested and sang:

While filling oor pails it wis fun.

We a’ went tae the berry picking,

Aye, when we were young.

Charlotte Munro

Oh my, what a delight for the eyes of a traveller lassie who’d been locked off the road for a full two months! The berry campsite was brimming with trailers, hawker’s lorries, vans and lurcher dogs. The women, with heads of thick hair wrapped in multi-coloured head squares, were all cracking and gossiping. Younger lassies showed off slender figures, flashing smiles and gold-ringed ears. Men were spitting on their hands and doing deals over horses or motors or whatever they fancied. I felt the giant butterflies bursting into life inside my young breast—I was home, back on the green. If you’re not a traveller then you’ll be thinking I went mad. If you are, well, need I say more?

Mary, Renie and Babsy circled round and hugged me until I worried if I’d have a chest to breathe again. That was a grand welcome, but nothing like the one wee Tiny gave me. I swear if yon dog could talk he’d have poured the love of every day he’d missed me through a tottie wet tongue right into my ear.

Without the bus, things would never be the same again, I knew that much, but I’d settle for the Eccles caravan and large Ford van Daddy had replaced it with. I named that motor Big Fordy. (Remember Wee Fordy? Makes sense, doesn’t it?)

My parents realised they’d made a mistake by taking me off the road. I later heard Daddy tell Mammy that ‘Yon lassie o’ oors is like me when I was a youngster, Jeannie—a thoroughbred gan-aboot.’

Mammy nodded and said, ‘Aye, Charlie, I’m thinking she’s a throwback from the old yins.’

Something completely different had become a fixture in our circle—a male! Mammy’s sister Annie’s boy Nicky had joined us, and was to prove invaluable as Daddy’s right-hand man with the spray-painting. He had his own caravan, and was the reason frying steak was on our menu from then on.

Someone else had joined our crew whilst I was trying out the scaldy life—Portsoy Peter. He was a pal of Daddy’s, who went back as many years as my parents did. He hailed from Morayshire. I can say this, with hand on heart, that more folks than I care to remember came through our lives, but no one sticks so vividly in my mind as this expert of the gab art, Portsoy, King of the Con! He was a con-artist second to none. Soon I’ll share some of his expertise with you, but first I’d like to tell you about ‘Wullie Two’.

2

A CONVERSATION WITH WULLIE

For as long as I could go back in my mind, Wullie Two was part of the ‘berries’. Nobody knew much about him but the minute a fire was lit, there was Wullie. ‘A wee bit simple,’ some would say. Others would just say he never grew up. He wasn’t violent or anything like that, in fact the opposite was the case. He would go to the pictures with us young ones, sit on the back of the seats and shout out at John Wayne, ‘Git yer heed doon, man, the Indians are coming!’ He believed that the film being projected in front of his eyes was really taking place. Then we would all shout at him, ‘Git yer heed doon, Wullie, the picture-house man wi the torch is comin.’ This of course was double the entertainment for us, laughing ourselves silly at the antics of Wullie as he dived below our feet, thinking he’d be turfed out before the film had ended.

This is a conversation I had on a quiet Sunday with the guid lad.

‘Why are you called “Wullie Two”, Wullie?’

‘Weel, ma Mammy had four laddies, an as she wisnae very good wi names she cried us all the same. Wullie One, Wullie Two and so on.’

‘But how come she called you all Wullie?’

‘The scaldy hantel call a man’s private johnny, a wullie, and as ma faither used his tae give us a “jump start”, then that’s why we’re all cried that.’

‘Have you any sisters?’

‘Aye.’

‘How many?’

‘Only the one.’

‘What’s her name?’

‘I dinna ken, but she wis a beautiful lassie.’

‘Have you forgotten her name?’

A silent pause made me wonder if I’d upset him somewhat, so I asked if he didn’t wish to answer. His response turned me silent.

‘Ma sister nivver had a name, neither had she a man tae herself.’

‘Was she fussy with lads?’

‘No, she fell in love with a greyhound, and when she had a litter o’ pups ma Dad sent her packing.’

I tried to stifle the surge of laughter welling in my throat, but I don’t believe anyone could hold back after such a comment, so I let rip. When I’d composed myself Wullie’s next words sent me back into overdrive.

‘Ye may well laugh, but she’s rich noo, yon sister o’ mine, because ivery yin o’ yon dugs went on tae tak first place on Scotland’s racetracks, ivery yin!’

‘Oh, Wullie, what a man you are. Where were you born, anyroad?’

‘Ma Mither found me sleeping in a pot o’ pea an ham soup, huddlin’ in ahent a puckle boilt bones.’

Just when I thought my sides would split his finishing comment left me in stitches.

‘It was rare an’ warm in yon pot!’

So there you have it, folks, my memory of a born comic. No script, no rehearsal, just a pure untapped rarity of golden delight. However, the more I think about Wullie, the more a certain Rattray man’s words keep turning over in my head. His nickname was Shakims, and as he said, ‘Who’s the more foolish—him who tells the tale or him who believes it?’

3

A KINDRED SPIRIT

Here is the story of Mac.

The July sun was never as hot as it was that day, so once I’d reached the grand sum of one pound and ten shillings worth of berries picked, I dropped the wee metal luggie tied round my waist and headed home. The berry farmer wasn’t too pleased with my early withdrawal from his heavily-laden fruit field and called after me, ‘Where are you going, young un?’

I had hoped he wouldn’t miss me, but as the rain had poured solid the two previous weeks, this cratur was desperate to see all hands on deck to transfer his yield of fruit, which was hanging heavy, from bush to baskets. I had no wish to lie, so as the pinky of my right hand had earlier suffered the fierce sting of a big orange and yellow bumblebee, I used this as my excuse. He tutted and warned me to ‘mind and make sure you work double hard the morra.’ Poor man, little did he know cousin Nicky had removed the bee’s painful spike over two hours earlier, and although the pain was still there it certainly didn’t warrant a ‘sicky’. But after I’d soaked my head under the waterspout behind the farmhouse I was more than glad that the day’s berry picking had come to a close. Betsy Whyte was outside her trailer boiling a kettle of tea water on an iron chittie and waved over to me. ‘Aye, Jess, it’ll be a sunbathe you’ll be up tae, lassie.’

I laughed and asked her not to tell Mammy. Betsy was one of the nicest travelling women I’d ever met. Little did I know that some day in the near future she would be the greatest traveller writer of her time. (Both her books—Yellow on the Broom and Red Rowans and Wild Honey—would be renowned as classics.)

But you know something, if I hadn’t left the drills that day then my meeting with Mac might not have taken place and a great deal of tales would have passed me by.

I went into the trailer where Mammy had, before going to join her brood on the field, a massive pile of drop scones cooling under a flannel dishtowel. Putting one in my mouth and another in my pocket for later I lay down to sunbathe under the hotter-than-ever sky. Just as my eyes felt heavy and Father Nod crept serenely over my body I was brought to life by a large being shading out the sun.

‘Hello, lassie, I’m looking for my mate, Portsoy Peter. I was told he was hitching his yoke with Charlie Riley.’

I sat up to say he’d found the right place, but Portsoy wasn’t in. ‘I think he’s at Perth and will be back about tea-time,’ I told the stranger, then continued: ‘I know that because he asked Mammy what was for tea, and when she telt him tattie soup and stovies he said there was no way he’d miss out on such a cracking meal.’

The big man asked politely if he could wait at our fire. ‘I’ve come a fair distance tae see my old mate, it would be daft tae go away without a blether.’

It was nearing three in the afternoon so I enquired if this visitor fancied a cuppy?

‘Only if I can have a share o’ yer scone,’ he mused.

‘I’ll get you another one, Mammy’s made a wayn o’ them. What’s yer name by the way?’

‘Mac, I’m simply called Mac.’

‘What else, surely there’s more to your self than three letters?’

‘Well, you can put a lot into those three wee letters, lassie.’ He smiled as he settled himself down onto the warm grass and lay beside me. Shielding his eyes from the sun’s glare with his bunnet, then inserting a blade of grass between a fine mouth of shiny white teeth he told me how he came to be.

It was 1918 and old Widow Macgregor had just made safe her tent fire for the night. All of a sudden the flap door was wrenched back and a young lassie, still with the freckles on her face and the red on her cheeks, thrust a new born baby boy into the hands of the startled elderly woman. ‘I canna keep it,’ she cried, ‘I dinna ken how tae.’ Those words were the youngster’s parting call before she planted a soft kiss on the infant’s brow and was gone into the dark night. The old woman had seen many bairns into the world, so she knew how to twine-tie the cord and wash its tiny frame. What worried her more was her awareness that it had not long left the womb, because it takes no longer for a new human to die than it does for a featherless chick deserted in the nest. Without a minute wasted, she wrapped the bairn in a shawl and huddled off into the night toward the tent of Marion Macdonald. She had a few wee ones. The widow had heard them playing in the birch woods and knew they lived less than a mile away up toward Tulimet. The tents were in darkness as she arrived by the moonlight’s guidance.

Without waiting for permission, she forced her old frame in through the door of the Macdonalds’ tent. ‘A stupid wee lassie has had herself a baby, Mrs Macdonald—have ye the breast milk for it? Look, the poor wee thing hasn’t even tasted a drop yet, I fear death is in the waiting for it if it doesn’t see any sustenance.’

‘Oh dear, I’m fair sorry for the mite, but my youngest is over the year and doesn’t need milk. Mine dried up last month. But the lassie Macpherson might be able to help, did she not bury a stiff-born infant just the other day?’

The old woman, saddled with her precious burden, said she’d heard of the sad case, but were the Macphersons not over seven miles away? ‘The baby would never survive that distance,’ she said, biting into her knuckles in desperation.

‘Not if my Jamie runs with him’, answered Marion. Her Jamie was thirteen and ‘could run with the Monarch’, she proudly told the old woman. Marion speedily ripped out sheep’s wool she’d sown into her children’s mattress and began covering the wee boy’s head and vulnerable back. Then she tied pieces of muslin all round his tiny frame, leaving a small hole for air at his mouth. As if packing a very valuable piece of china she placed the baby into a hessian sack and tied it to Jamie’s back. To emphasise the importance of his task she placed two strong hands onto his young shoulders and said, ‘for God’s sake, laddie, go like the wind, for this wee bundle hasn’t an hour of life left in him.’

Jamie took off into the night as sure-footed as the deer, and in no time was holding out the tiny parcel to the young mother in the throes of bereavement.

Soon the wee baby boy was suckling like mad, a life saved by the expertise of the travelling people. Sad to say, though, his adopted mother fell ill with fever, and in his eleventh month her life was cut short. Her sad husband, unable to cope, begged a farmer and his wife to take the bonny healthy boy. Which they did and brought him up as their own.

‘And here I am, lassie, lying here on the grass beside you this very afternoon.’ Mac finished his tale, turned onto his stomach and went to sleep.

I was intrigued, what a marvellous story. I had to hear more about my new friend.

‘You still haven’t told me why you’re called Mac.’ I awakened him with a prod into his ribs.

‘Then you haven’t been listening, lassie,’ he said, rolling onto his side.

‘I heard every word you said, it was fascinating.’

He then reminded me: the first old woman’s name was Macgregor, the second was Macdonald, the third... Macpherson.

‘Oh, I can see it now, their names all began with “Mac”.’

‘You’ve got it!’

‘But why didn’t you take the farm-folks’ name—surely they gave you theirs?’

‘I did! They were called—Macmillan!’

I laughed, so did he, then we shared another cup of tea and scone.

I liked this man, I felt a kindred spirit, and wanted to know more about his fascinating life. But soon the family would be home from the berries. I had a fire to kindle, tatties to peel and a kettle to boil.

The night settled itself around the campfire, which began to be crowded with lads and lassies whirling up a ceilidh. Some sang the old ballads, while others played an instrument. We were graced with a blaw from Mammy on her mouthie before she gave everyone a toe-tapper on her Jew’s harp. She could fair make that wee piece of metal curl and twang between her lips, could my Mam! I told a ghost story or two, which saw old biddies pull collars tighter round their necks. Such were the horrors that fell wordily from my mouth, even I found it hard to believe they were ‘made up tales’ out of my head of many characters. At last Mammy scolded me for frightening the bairns, who’d scurried away to their beds. A tall lad from up north sang several Jacobite songs, which went down very well with his captive audience. But, strange to say, this particular choice of song didn’t stir a single clap from my pal Mac. Later, when everyone had bedded down for the night, I asked him if he had had a ‘whine’ with the singer.

‘Not at all, lass, it was those Bonnie Prince Charlie stories that I canna feel much for,’ he answered.

‘I love to hear them’, I told him. ‘It makes me feel all fuzzy inside to think he might have been our last king.’ I then proudly added, ‘what about our ancestors who gave their lives and their lands for freedom’s sword?’

‘Huh, what rubbish, that word freedom is as Scottish as haggis!’

I looked on in bewilderment while he ranted on about how, after Culloden, all our hardy beef was scoured out of the land and we were forced to live off mutton because that was all there was. If our English neighbours hadn’t felt pity on our starving bairns and showed us how to survive the winters by eating sheep offal in its stomach, then a hell of a lot of us would have perished. ‘Why do you think Robert Burns wrote a poem to the haggis? Because it fed the poor, that’s why!’

Those words left my imagination in overdrive, but I hadn’t enough insight to understand what they meant, so I prodded Mac to say some more. But he would go no further and told me to find out for myself.

He fell silent for a while before going into Portsoy’s caravan (who, by the way, hadn’t arrived back from Perth). When inside he called to me through the open door, ‘Jessie, do you want to hear another side to that historical episode of yon Stuart?’

Now, anyone who knows me would swear to walk forever backwards if I didn’t want to hear stories about my Scotland, fictitious or otherwise. So in no time I was sitting with knees under my chin, watching and waiting as Mac opened an old tattered suitcase he’d earlier slipped under Portsoy’s bed, and carefully removed a single jacket, a pair of trousers and three or four odd socks, and put them on the caravan floor. Concealed at the bottom of the case he lifted out an old bulky journal that had seen better days, and laid it gently down. ‘This, lassie, is tales told to me over the years by many, many traveller folks. You see, because of my beginnings I always felt drawn to the tent folks. You could say I was magnetically pulled into their midst by an invisible force outwith my control. The ancient stories fascinated me, and thanks to my adopted parents I was schooled in reading and writing. Now, I dare say many of the tellers were reluctant to see the spoken word go on paper, but it’s amazing what a wee dram and a few fags could do. However there were a damn sight more that would not be bought for love nor money. I had a fierce arm chuck me into a grimy puddle many a time by those who believed in staying loyal and forbidding the writing down of the sacred tales. So a lot of the time I had to rely on memory. This story, though, I did have the blessing of the teller to put through the pen. Do you want to hear it?’

‘Without a doubt.’

‘Then, Jess, listen and do it well, for there’s many who would spit in your eye for its hearing. I do hope you don’t suffer the same fate as those first poor souls who dared tell the story of—

4

THE SEVERED LINE

Who among us in Scotland has not heard of ‘The Young Pretender’, son of James Edward the ‘Old Pretender’, the rightful Stuart King of Scotland? No doubt very few. It brings the musician out in all of us, doesn’t it, to hear the stirring battle call of ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ himself, and the Jacobite rising of the ’45. How bold and daring were the exploits of his followers; lengthy novels depict his brave attempt to bring the Stuarts back their kingdom of Scotland, their birthright throne.

But! What if I told you a different tale, with twists and turns, and evil lies, hmm?

Come with me now to Rome where a lady lies, writhing and screaming in the last throes of her pain-wracked labour. Nursemaids, sweating and scurrying to and fro with hot water and swathings of cooled cloths, await the arrival of the King’s new heir.

Outside, a fierce thunderstorm adds its tension to a nerve-stretched night. It is four a.m., the darkest hour; the lady pushes for the last time and a new-born scream cuts through the waiting ears of a small army of servants and doctors. The heir apparent has arrived. The clan chiefs, far off in tiny Scotland, will breathe hope again.

The new mother opens her exhausted eyes, and for a moment she sees on the face of her doctor a frightened look. He hands the baby over to a trembling nurse, who swiftly wipes its tiny frame before laying it down beside its mother, who pretends to be asleep. While her nurses make the place ready for his Majesty’s arrival the lady pulls back the shawl to see she has... a beautiful daughter! The last thing she remembers before exhaustion sweeps over her is an enormous crack of lighting that lights up the entire room, but strangely leaves her infant clouded by a dark shadow.

When at last her eyes opened again it was her dear husband holding both her hand and the tiny fingers of their new–SON. The lady said nothing because she knew the chiefs would not accept a female child. She kept silent and went along with the lie that she had given birth to a healthy son, but she had to know if her natural child was alive or not. When her health returned she forced her handmaiden to tell the truth.

‘It was not to be disclosed to another living soul, Ma’am, but in the same hour your child was born a scullery maid brought forth an illegitimate son. It was his Majesty’s orders that the babies be switched.’

‘Where is the kitchen lass, and does she still have my daughter?’ asked the lady, shaking with emotion.

‘Ma’am, she has been given a small dowry and, oh, please Ma’am, forgive me for telling you this, but she’s been sent to Scotland!’ The maid fell at the knees of her mistress and sobbed.

The Lady gently lifted her servant’s head and said, ‘Please tell me she has the child.’

‘Yes, Ma’am, the baby is with her.’

Those were blessed words to her ears. She knew that her baby was lost to her forever, but at least a royal Stuart would grow, and, pray God, survive, within her rightful home on Scottish soil.

The scullery maid called her forced child Charlotte, and swore with every God-given breath to disclose to the lass, when the time was right, who she really was.

Within no time of their arrival in Scotland, in a part of Edinburgh, the scullery maid found a house of employment. Strangely, the wealthy family with whom she had settled took her child as well. Perhaps it was the distinctive blue of her eyes or maybe it was the bright red hair, one cannot say, but before long she was accepted as one of the family.

Within this family were three children who were privately tutored in the highest of education, music and the arts. When old enough, Charlotte joined them in their classroom and soon stood out as a bright and highly intelligent student.

Soon it was time! One night the woman whom she thought of as Mother sat young Charlotte, now eighteen, down and revealed the awful truth.

It was hard for her to understand the revelations pouring forth, and she at first refused to believe such apparent untruths.

‘It is the God’s truth, my lady. You are Scotland’s rightful heir.’

‘Then why do I not sit on the throne?’

‘Because the chiefs would have you silenced. They have word from the Vatican that a young prince, my rightful son, is as we speak being groomed to bring Scotland freedom.’

‘Then, mother, for that is who you will always be to me, time for planning.’

From that night onwards Charlotte lived only to be Queen!

Three more years passed, and having reached a certain status under the roof of her mother’s employers she spread, not the wings of a fair dove, but the sharpened claws of a fierce bird of prey. Soon she found a position nursing in a home for recovering soldiers. In no time she caught the tired eye of a captain home from fighting in some far-off land. He was of blue-blooded stock with property, just what she was looking for. Her claws gently dug in to the heart of this man twenty years her senior. Before fewer than ten months had passed she was the honourable Lady Lister, seated in her new home three miles north of Inverness, with her so-called mother installed as housekeeper, and keeper of the secret. More important than anything else she was pregnant. ‘If the clans do not accept my blood, then they will accept my son.’ She swore her womb carried a male child. If it did not, then she would continue producing children until it did! For this was Charlotte’s plan.

But oh, how the best-laid plans fall prey to fate.

Much to her horror her husband fell, fatally wounded, during a skirmish in France, and never lived to see his twin sons being born. More’s the blessing on him, because the babies were so badly deformed that Charlotte dared not let any eye fall on them. How could she now approach the chiefs? This was not foreseen. But so deep had her intent become that she refused to be daunted. She would find a way, right or wrong.

There had still been no sign of the ‘impostor’. Perhaps he would refuse an invitation from the now restless clans. After all, having lived a charmed existence under the cloak of rich indulgence in the fine palaces of Rome and France, he was hardly likely to put his life in danger for such a futile cause.

Seventeen years passed, her sons never having set an eye upon an open door or window. She herself found it difficult to spend any more time than necessary in that stinking room in the attic of Lister House, set in the thickest of Caledonian forests. Only her once mother, the now old and bent housekeeper, fed and cared for those sad cripples who had once held all her hopes of bringing the crown home from those greedy southern jailers.

Charlotte’s plan to put Scotland into the Royal Stuarts’ hands was indeed honourable, but she was becoming desperate, and desperate people do dishonourable things. In the days ahead, not only did she stoop to unmentionable depths, but the Devil himself would have been proud of her, to say the least.

I now take a moment, reader, to tell you that my host, narrator of this historic tale, closed his journal and reminded me of the time, which was entering a summer midnight hour. ‘I think our friend Portsoy is for staying the night in Perth, lassie. Do you think he’ll mind me kipping down on his bed?’

Mac certainly looked the worst for whatever journey he’d taken that day, and after all the poor soul was over sixty. I, however, was only fifteen, and this story would not keep in my head. I needed desperately to know its end.

Just then, before either of us could say a thing, the door opened and there was my Daddy with the man himself, old Portsoy Peter.

‘This daft Morayshire man broke doon upon the Perth road,’ laughed Daddy, ‘I found him hitching a mile north o’ Scone.’

I found it hard not to laugh at the poor soul’s predicament, because he had been blowing a hardy trumpet that very morning about how his new-bought Bentley ‘was the maist reliant motor vehicle in all the countryside.’

But when he saw his dear friend Mac lying sprawled upon his bed, storybook opened, he put the car aside for another day’s conversation. Daddy asked me to fetch a pot of tea while the threesome had a wee crack. He’d been away himself most of the day at Stirling selling a vanload of brock wool.

Although pleased, as I always was, to see my father safely home, I was also annoyed that the pair had interrupted Charlotte’s tale. ‘Are we going to find the end of our story?’ I prodded Mac on the arm.

Now, I know this seems a bit uncommon to say the least, given the ungodly hour, but Daddy said he’d haggled all day with the rag merchant and would take a tale before bedding himself. Portsoy, who’d heard Mac’s tales before, was also in the mood for hearing it again. So, after going hurriedly back to the beginning of the story for our added listeners, Mac continued with ‘The Severed Line.’

One day, while out walking in the thick forest with her old housekeeper, Charlotte was stunned to silence by the appearance of a small band of passing tinkers. It was not their lowly existence nor tiny abodes secured to bent backs that took her eye, but the fine fiery red hair cascading down a slender spine. The girl, Iona by name, was a mere fifteen, if that, with flashing green eyes and oh! that so thick red hair—the hair of the Royal Stuarts.

Charlotte was already sealing the fate of this impoverished band, and before that fateful day slowed to its end she had paid two henchmen to slit all their throats. All but the wench. She was gagged, bound hand and foot, and brought into the stately home. There she was forced up the winding metal stairway and thrown into the den of Charlotte’s twin sons. ‘I shall surely have my heir to this country now,’ she cried, as she shook her fist at the heavens above and swore that this was a God-given day.

The two sons had grown up as twisted in mind as they were in their maimed bodies. The innocent tinker girl was subjected that night to the most horrific attack upon her small frame. Had the housekeeper not entered later to remove her shattered and torn body, no one knows what they would have ended up doing to Iona that night. Next day Charlotte insisted her sons taste more, and in she threw an exhausted and half-dead girl. This she did daily for a week, allowing both her sons to abuse her at will.

After that she imprisoned Iona in a tiny basement and waited. Within two months her housekeeper brought the news—Iona was pregnant. On the old housekeeper’s advice a warmer, more comfortable apartment was prepared to imprison the mother-to-be. After all, it would be a royal Stuart who was coming once again to the Scottish nation, one whom the clans had been awaiting for a long time. They would listen and believe Charlotte when the truth was shown to them. She would be the Queen Mother and instruct the new heir. Oh, how she schemed and plotted!

Now, while all was being prepared, the old housekeeper began to think remorsefully on the road her life had taken. She could feel that her life was slowly dwindling and felt it wasn’t Charlotte’s fault but hers for disclosing the truth in the first place. She thought on the husband who had died far from his estate. She thought about the sadly malformed twins who had never been kissed or cuddled by a loving mother, and now poor Iona, whose family had been murdered for sake of this woman whom she had nurtured.

Any day now Iona would give birth and then what? What if it was a girl? Would she be thrown into the den of the twins once again? What if it was indeed a son? Of course, with her task complete, the young mother would never see another day. When would all this evil end? The old woman was the only one who could change things. Next day she set out to do just that.

While Charlotte slept, she went into the girl’s room, and just as expected the baby was moving into position for birth. Dressing Iona, the old housekeeper silently led her out of the large house of Lister. On the way she told the lassie what Charlotte was planning to do. The pair walked on until, exhausted, they came to the shore. Iona was led into a small cave to hide and have her child without help. You see, the old housekeeper had her own safety to consider.

Charlotte was seething with the red anger when she found that Iona and the housekeeper had gone, and she rode out to procure once again the assistance of her two henchmen who were living in a dark hovel nearby. Riding madly through the thick forest the three came upon the old woman, who lied and said that when she rose that morning she too had found Iona’s bed empty and set out to find her ‘before you, my mistress, awakened.’ Before walking off she called back to the death-minded threesome that she would take care of the boys, then she was gone into the forest.

As the day’s sun was settling into the night sky, they were searching every inch of shoreline until a child’s cry brought Charlotte and her hired killers to the cave. As they dismounted they saw a small figure silhouetted against the horizon; it was Iona standing above them on a ledge.

‘Have you a son for the throne of Scotland, lassie?’ Charlotte cried up to the visibly shaken girl.

‘Aye, mistress, see for yourself. I’ve done ye doubly proud.’

Charlotte could hardly believe her eyes, for there, lying wrapped in a torn shawl, were not one but two sons, each already showing a fine red hairline.

‘When I have my babies you know what to do with the tinker,’ she whispered.

The henchmen nodded in unison.

Iona was more than aware of her impending doom, but she was not going to go without seeing Charlotte’s face when the truth was revealed.

For as the lady of evil stooped to bundle up her heirs, two tiny heads rolled from their bodies at her feet!

‘See, wicked Charlotte, see your severed line!’ Those were Iona’s last earthly words as she leapt to a watery grave.

Charlotte screamed towards the heavens, blaming everybody but herself.

‘I will repeat this, others will be found,’ she screamed over and over again.

Those men of depravity had come even to their limit when witnessing this dreadful scene, and without payment they rode off into the dark forest, hoping never to set eyes upon Lady Charlotte again.

However, when she at last arrived home yet another horror was to meet her eyes that day, because the old housekeeper had torched Lister House with Charlotte’s twin sons locked within its walls. Charlotte and Lister House were never heard of or seen again. There are those who said she cursed Scotland from that day, and swore that the impostor would fail in any attempt he made to unite the clans. And that he did. Strange!

‘Great story,’ whispered Daddy, not wishing to wake Portsoy who had fallen asleep earlier. He turned and whispered to me, ‘Mammy will want to know why you and me hadn’t bedded until the second hour of the night, better no tell her we were tale telling.’ I smiled and promised, but hey, who could fool Mammy?

He then went off to his bed. But not I, no, I was still standing on that ledge with Iona watching the babies’ wee heads rolling at Charlotte’s feet. How could I sleep? I just had to ask Mac if there was any truth at all in this tale. He never answered. I couldn’t help but smile to myself, though, as I watched him take those flashing white teeth of his that I’d admired all day, and pop them into a glass half-filled with water.

Next day the berries saw us swelling the purse. Mammy was rare pleased and thanked God for filling the drills with juicy fruit and the heavens with the sun. I wanted to hear more of Mac’s tales, but he had lots of cracking to do with old Portsoy. I stood upon a wee stool and peeped through the window, to see the same glass Mac’s teeth had snuggled into the night before filled to the brim with ‘the cratur’. ‘Oh well,’ I thought, ‘thon’s a wild bit o’ cracking taking place in that wee trailer this night, best I forget the tales for now.’

I wandered off and soon found a dozen or so girls of my age hanging about the farmer’s giant hay barn. ‘Let’s monkey swing,’ said one of the lassies. This game was to swing from the rafters and then drop down onto the hay, great fun it was too. The usual practice was to aim to go from one end of the barn to the other without falling. Whoever slipped first stood out, and so on until only one was left. Well, I can’t say exactly how or why, but you-know-who fell and landed, not on the soft spongy hay, but on a great rusty pitchfork concealing itself under a layer of straw. Up it went into an inch of my foot. Two strong lassies dragged me squealing like a porkie all the way from the barn to our spot at the far end of the campsite. Every traveller in the place was up and over to see why my foot was dragging a pitchfork behind it. ‘Take that lassie tae the doctor,’ was one concerned voice. ‘God, wid ye look at thon fit, it’ll need tae be cut aff!’ was another. My mammy knew exactly what to do, and soon my foot with the hole was steeped in an almost boiling basinful of water and Dettol. Half an hour later I was sat, my foot washed and swathed in miles of torn cotton sheet strips, with a cup of tea and a scone. All well wishers and nosy parkers gone, I hopped to bed with a foot as sore as the wildest toothache, and Mr Nod definitely did not come within a mile of me that night.