Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

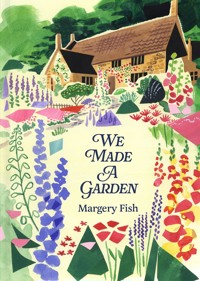

First published in 1956, We Made a Garden is the story of how Margery Fish, the leading gardener of the 1960s, and her husband Walter transformed an acre of wilderness into a stunning cottage garden, still open to the public at East Lambrook Manor, Somerset, England. This is now one of the most important books on gardening ever written. A beautiful and timeless book on creating a garden. Margery Fish turned to gardening when she was in her mid-forties and went on to develop the whole concept of a cottage garden. She had a love of flowers coupled with a passion for nature and made an intensive research into the traditionally grown plants with which cottage gardens in Britain were once so densely planted. In this classic owrk, she recounts the trails and tribulations, successes and failures, of her venture with ease and humour. Topics covered are colourful and diverse, ranging from the most suitable hyssop for the terraced garden through composting, hedges, making paths to the best time to lift and replant tulip bulbs. Her good sense, practical knowledge and imaginative ideas will encourage and inspire gardeners everywhere.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 215

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

We Made a Garden

Margery Fish

Contents

Foreword by Graham Rice

Introduction

The House

The Garden

The Lawn

Making Paths

Clothing the Walls

Hedges

The Terraced Garden

Planting

Staking

Gardening with a Knife

Watering

Dahlias

Some Failures

Composting

The Value of Evergreens

We Made Mistakes

The Water Garden

Rock Gardening

The Paved Garden

The Herb Garden

Early and Late

Mixed Borders

What Shall I Plant?

Living and Learning

Plant-name Changes

Index

Foreword

This is the book which started it all for Margery Fish and for gardeners around the world for whom she and her garden have been such an inspiration. As war approached in the late 1930s Margery and her husband Walter bought a house out of London, East Lambrook Manor in Somerset, and set about restoring the house and making a garden. This book is an account of their adventure.

For the first few years that they lived at East Lambrook, they divided their time between Somerset and London – Walter was editor of the Daily Mail and Margery had been assistant to Lord Northcliffe, its proprietor. Clearly, the garden had to be easy to look after; they both also believed that it should be in harmony with the stone house, and they wanted it to be presentable all the year round. These ideas inspired both her gardening style and her writing; and through this book, the seven others and her many magazine articles she brought her influential ideas to a wide audience.

Margery and Walter were very different characters. One of the recurrent themes of We Made a Garden (originally proposed under the not very catchy title of Gardening with Walter) is the uneasy horticultural relationship between the two – Walter preferred bold and colourful plants and fought a not always good-humoured battle with his wife to ensure prominence for his dahlias. Margery, who hated dahlias, was more interested in primroses, double daisies, hellebores and other less brash varieties. But their devotion to each other transcended such differences of taste in spite of Walter’s sometimes thoughtless disregard for her favourites – which she herself lovingly recounts here.

At first she tells Walter his beloved dahlias are ‘only fit for a circus’; later, as his strength deserted him, she planted his dahlias for him even though she was also secretly relieved when they failed to survive their winter in storage; then, after he died, she took pleasure in seeing the few remaining varieties coming up year after year. The book is an account of their relationship, as the original title indicated, as well as the garden.

Since Margery Fish died in 1969 her garden has enjoyed mixed fortunes but in recent years has been restored, looked after carefully and is open to visitors daily for much of the year. Margery’s nursery, through which she disseminated such a variety of choice plants, is again flourishing, and varieties which she herself discovered and introduced to gardeners are again being made more widely available. Her evocative and infectious writing style, coupled with her astute observation of the plants themselves, has long inspired gardeners and continues to do so. She helped make our gardens the way they are.

Graham Rice, 2002

Introduction

When, in 1937, my husband decided there was a likelihood of war, and we made up our minds to buy a house in the country, all our friends thought we’d choose a respectable house in good repair complete with garden, all nicely laid out and ready to walk into.

And when, instead, we chose a poor battered old house that had to be gutted to be livable, and a wilderness instead of a garden, they were really sorry for us. They were particularly sympathetic about the garden. Redoing a house could be fun, but how would two Londoners go about the job of creating a garden from a farmyard and a rubbish heap?

I have never regretted our foolhardiness. Of course, we made mistakes, endless mistakes, but at least they were our own, just as the garden was our own. However imperfect the result there is a certain satisfaction in making a garden that is like no one else’s, and in knowing that you yourself are responsible for every stone and every flower in the place. It is pleasant to know each one of your plants intimately because you have chosen and planted every one of them. In course of time they become real friends, conjuring up pleasant associations of the people who gave them and the gardens they came from.

Walter and I had several things particularly in mind when we made the garden.

The first was that it must be as modest and unpretentious as the house, a cottage garden in fact, with crooked paths and unexpected corners.

Next it must be easy to run. When we bought the house we were living in London, and for the first two years we divided our time between London and Somerset, so our garden had to take care of itself for much of the time. We designed it with the idea that we’d have to look after it ourselves, and though there have been times when we had regular help they were brief and uncertain, and we knew we’d soon be back where so many people are today, depending on a little casual labour when we can get it.

Since Walter died I have had to simplify it even more, as the garden can only have the odd hours that are left over in a busy life. He made me realize that the aim of all gardeners should be a garden that is always presentable – not a Ruth Draperish garden that has been, or will be, but never is at its best. We don’t apologize for our homes because we keep them garnished regularly as a matter of course, and I have never understood why we don’t feel exactly the same about a garden.

Another thing he taught me was that you mustn’t rely on your flowers to make your garden attractive. A good bone structure must come first, with an intelligent use of evergreen plants so that the garden is always clothed, no matter what time of year. Flowers are an added delight, but a good garden is the garden you enjoy looking at even in the depths of winter. There ought never to be a moment when it is not pleasant and interesting. To achieve this means a lot of thought and a lot of work, but it can be done.

The House

The house was long and low, in the shape of an L, built of honey-coloured Somerset stone. At one time it must have been thatched but, unfortunately, that had been discarded long ago and old red tiles used instead. It stood right in the middle of a little Somerset village, and made the corner where a very minor road turned off from the main street. There was only a narrow strip of garden in front, and not very much behind, but we bought an orchard and outbuildings beyond so that we had about two acres in all. A high stone wall screened us from the village street, and there was a cottage and another orchard on the other side.

You can’t make a garden in a hurry, particularly one belonging to an old house. House and garden must look as if they had grown up together and the only way to do this is to live in the house, get the feel of it, and then by degrees the idea of a garden will grow.

We didn’t start work outside for nearly a year, and by that time we felt we belonged to the place and it belonged to us and we had some ideas of what we wanted to do with it.

It was on a warm September day when we first saw the house but it was such a wreck that Walter refused to go further than the hall, in spite of the great jutting chimney that buttressed the front. Then the long roof was patched with corrugated iron, the little front garden was a jungle of rusty old laurels and inside an overpowering smell of creosote, newly applied, fought with the dank, grave-like smell of an unlived in house. ‘Full of dry rot,’ said Walter, ‘not at any price,’ and turned on his heel.

For three months we tried to find what we wanted. We looked at cottages and villas, gaunt Victorian houses perched uneasily on hilltops, and snug little homes wedged in forgotten valleys. Some were too big and most too small, some hadn’t enough garden and others too much. Some were too isolated, others so mixed up with other houses that privacy would have been impossible. We lost our way and had bitter arguments, but we did discover what we didn’t want. I couldn’t see Walter in a four-roomed cottage with a kitchen tacked on to one end and a bathroom at the other, and I had no intention of landing myself with a barn of a place that would require several servants to keep it clean.

We were still hunting in November when our way took us very near the old house so summarily dismissed in September, so we turned down the lane which said ‘East Lambrook one mile’, just to see what had happened during those three months.

Quite a lot had happened. The front garden had been cleared of its laurels and the house looked much better. Old tiles had replaced the corrugated iron on the roof, and inside the walls had been washed with cream and the woodwork with glossy paint.

It is one of those typical Somerset houses with a central passage and a door at each end, so very attractive to look at and so very draughty for living. That day we thought only of the artistic angle. It was late afternoon and the sun was nearly setting. Both doors were open and through them we caught a glimpse of a tree and a green background against the sunlight.

That day I got Walter further than the flagged passage, and we explored the old bakehouse, with its enormous inglenook and open fireplace, low beamed ceiling and stone floor, and a gay little parlour beyond. On the other side was another large room with stone floor and an even bigger fireplace, and at the far end a lovely room with wonderful panelling. We both knew that our search had ended, we had come home.

I cannot remember just what happened after that but I shall never forget the day when the surveyor came to make his report. It was one of those awful days in early winter of cold, penetrating rain. The house was dark and very cold, and the grave-like dankness was back, in spite of all the new paint and distemper. The surveyor, poor man, had just lost his wife, and was as depressed – naturally – as the weather. Nor shall I ever forget Walter’s indignation with the report when it did come in. The house, while sound in wind and limb, was described as being of ‘no character’. We didn’t think then that it had anything but character, rather sinister perhaps, but definitely character. Since then I have discovered that the house has a kindly disposition; I never come home without feeling I am welcome.

Having got our house we then had to give it up again so that it could be made habitable. For many months it was in the hands of the builders and all we could do was to pay hurried visits to see how things were going, and turn our eyes from the derelict waste that was to be the garden. Sometimes I escaped from the consultations for brief moments and frenziedly pulled up groundsel for as long as I was allowed. Walter never wanted to stay a moment longer than business required and it worried me to go off and leave tracts of outsize groundsel going to seed with prodigal abandon. My few snatched efforts made very little impression on the wilderness, but they made me feel better.

It was late in the summer before we could get into the house, and some time after that before we were able to get down to the garden in earnest. All the time we were clearing and cleaning in odd moments, working our way through the tangle of brambles and laurels and elders, and thinking all the time what we would do with our little plot. We both knew that it had to be tackled as a whole with a definite design for the complete garden, and we were lucky in having plenty to do while our ideas smouldered and simmered.

The Garden

The garden that went with the house was divided at the back into two tiny gardens, with walls and small plots of grass. We supposed that these went back to the time when the house had been two cottages.

In addition to the walls dividing the two little gardens at the back another wall divided us from the barton, and beneath all these walls someone had amused himself by making banks and sticking in stones vertically, like almonds on a trifle. We imagined the idea was a nice ready-made rock garden for us to play with. The first thing we did, when we really set out minds to the garden, was to remove all the walls and stones and pile them up for future use. They were quite a problem, those piles of stones, as they were moved from place to place as we dealt with the ground where they were piled. I could not see how we should ever use them all.

The high wall that screened us from the road was finished in typical Somerset style with stones set upright, one tall and then one short. I have never discovered the reason for these jagged walls and I don’t think they are at all attractive. I asked my local builder and all he could suggest was that it made a nice finish. I can think of more attractive ways of solving the problem without such a lavish use of big stones.

There was great scope for planting between the stones and Walter suggested I could get busy on the top of the wall while we decided what to do with the rest of the garden. So I bought a few easy rock plants and sowed seed of valerian and alyssum, aubrietia and arabis to clothe those jagged rocks. The great heaps of stones were at that time right up against the wall and I had to clamber up them each time I planted anything, and later when I wanted to water my little family. The watering was usually done after dinner, and those were the days when one donned a long dress and satin slippers for this social occasion – which one didn’t have to cook. I can’t think how I avoided turning an ankle as I had to clutch my skirt with one hand and use the other for the watering can while the stones rocked and tipped under my weight.

By degrees, of course, we got rid of all the stones. We gave away cartloads to anyone who would fetch them, mostly farmers who tipped them near farm gates to defeat the Somersetshire mud. We used up the best of them ourselves in time. We little realized in those days that as our schemes progressed we should buy far more than we ever had in the beginning.

Since those days I have had all the upright stones removed from the tops of our walls, and flat stones laid horizontally instead. I always thought the uneven finish very ugly and in times of stress when I have been casting round for more stones to finish some enterprise I have grudged so many large and even stones doing no good at all. Gone are all the little treasures from the top of the wall; instead clematises clamber about and climbing roses are trained over the top of the wall so that the world outside can enjoy the blooms as well. The rock plants, or descendants of them, are now growing in the wall itself. By tucking them into every available crack and crevice I can bring the wall to life long before the plants get going in the border below. Great cascades of white and lavender, yellow and pink prevent the wall from looking cold and bare in the early spring.

Having torn down all our little walls and obstructions so that we could visualize what the place looked like without them, our next job was to clear the barton – the yard in front of the outbuildings and between us and the orchard.

That job would have frightened most people, but not Walter. Anyone who knows anything about farming can imagine the piles of iron and rubbish that had accumulated during the years. We had bought the outbuildings, barton and orchard from a chicken farmer, so in addition to the farming legacies we had all the relics of the chicken era as well. And to add interest there were old beds, rusty oil stoves, ancient corsets, pots, pans, tins and china, bottles and glass jars, and some big lumps of stone which may at one time have been used for crushing grain.

A bonfire burned in the middle of that desolation for many weeks, until one day Walter announced that the time had come to level the ground for a proper drive into the malthouse, which we used as a garage. I was told I must find another place to burn the barrowloads of weeds and muck I collected every day. I can remember arguing, without result, that the place where the bonfire burned could be left while the rest of the barton was tackled. I think Walter was very wise in being so firm with me. The only way to get jobs done is to be ruthless and definite.

There was no rubbish collection in those days, which was undoubtedly the reason for the horrible collection of stuff we found. Small things, such as china, glass and tins, were collected by us in barrowloads and as a short cut Walter had holes dug in odd places and the stuff tipped into them. In the course of time, as I have put more land into cultivation I have run into quite a number of these caches, and have decided that it really does not pay to take short cuts. Luckily we now have a regular salvage collection and having retrieved the grisly mementoes they are banished for good and all.

Between the barton and orchard were two walls, and Walter suggested we could make quite attractive rock gardens against them and thus add colour and interest to the barton. It was only after I had given my enthusiastic agreement that I discovered he wanted some way of disposing of the bigger rubbish that couldn’t be buried. So all the old oil stoves, bits of bedsteads, lumps of iron and rolls of wire netting were distributed against the walls, and the rest of the job was handed over to me.

Luckily we had a garden boy working for us then and he was allowed to help me cover the hardware with earth, and between us we ransacked the heaps of stones for the nicest looking specimens. Neither of us had ever done anything of the sort before but we constructed what we thought were two very fine gardens.

Soon after this visitors appeared one day. One of them was an expert gardener and she didn’t get further than the first rock garden. I thought she was filled with admiration for our handiwork and was waiting for the applause. But I discovered she was trying to get up her courage to tell me that all the stones were put in at the wrong angle. Instead of tipping slightly inwards to make a good pocket of soil which would hold the rain, mine had an outward tilt so that the first really heavy shower would see a lot of the soil washed away and the water would run off what was left.

The stones had to remain as they were for several months, a monument to my ignorance, but one happy day a cousin with a genius for gardening visited us and remade the gardens for me. Although there is a distinct downward slope towards the gate he placed the stones to give the effect of level strata of outcrop, something I could never have dreamed of and have never ceased to admire. From the house the effect is a luxurious display of rock plants growing out of the wall.

I had very few real rock plants to begin with, and those that I had were very small, so the first season I kept up a succession of colourful effects with annuals. I do not know whether the soil was particularly good or as a beginner I took more trouble and followed instructions implicitly, or perhaps I was just lucky. Certainly I have never again grown such superlative Phlox Drummondii, dwarf antirrhinums, mignonette, zinnias, clarkia, godetia and candytuft, to mention only a few. For once, and once only, I achieved displays that really looked like the pictures on the packet, and I thought that it was all just too easy.

Not being an orthodox gardener I do not even now restrict myself to rock plants on these gardens, although I have quite a lot of them there. I like something a little more generous, so there are hyssops and ceratostigma, trailing potentillas and penstemon and, to give body a few dwarf shrubs, and against the wall such things as Veronica Haageana, coronilla, Salvia Grahamii* and S. Greggii*, and fabiana.

It was Walter’s idea to lay some flat stones in front of each of the rock gardens. He thought it would look more generous than having the gravel right up to the stones. To begin with they were only flat stones, but very soon I started planting between them and tried a few Dresden China daisies that had been given to me. The little daisies were an immediate success, because they enjoyed the cool root run between the stones, and I think found the ground that had been used for chickens produced a very rich diet. They increased so rapidly that it wasn’t long before I had every crevice filled with them, and in the spring when they were in full bloom the effect was very good.

Walter never showed much enthusiasm for the smaller plants I cherished so lovingly but the daisies were an exception. He wanted them everywhere, bands on either side of the path, and later when we planted flowering trees I was asked to encircle them with daisies.

I am afraid the manurial legacy from the chickens must have disappeared long ago but the daisies continue to thrive, and I think it is because I divide them so frequently. I give away hundreds every year and I meet them in the gardens of all my friends. There is only one thing to remember when dealing with these little daisies and that is to make sure the birds don’t uproot all the newly planted divisions. Nothing excites their curiosity or cupidity more, unless it is shallots. If I am doing a large area I find it saves a lot of time and casualties if I cotton them until they are firmly settled.

Having disposed of the rubbish we were at last able to consider the lay-out of the garden at the back of the house. We wanted it to be as simple as possible, as much grass as we could get and a generous drive to the old malthouse, which we were using as a garage. We had to leave enough room for a paved path from the house to the barton, and the rest of the level ground was to be taken up with a lawn that would stretch to the gate leading into the barton. We knew that the bigger the lawn the more spacious would be our garden. Just as a plain carpet pushes out the walls and makes a room bigger, so a wide stretch of uninterrupted grass gives a feeling of space and restfulness. Why, oh! why, will people cut up their lawns and fill them with horrid little beds? Usually the smaller the garden the more little beds are cut in the lawn making it smaller still. I can sympathize with the desire to grow more flowers, but one long bed grows just as many plants as a series of tiny ones, and avoids the restlessness and spottiness of small beds dotted about the lawn.

Walter was rabid on this subject and never ceased to exclaim at the foolishness of some of the people we knew. There was one garden in particular which we both liked when we first knew it. Then it was the rectory, and was just what a rectory garden should be. A wide flagged path led up to the house, turning at right angles to the gate. The rest of the garden was grassed, with fairly wide borders all round, under the high walls. The garden was not particularly well kept, nor were there very interesting plants growing in the borders, a good rector hasn’t time for that, but it was adequate and pleasant and just the setting for village fêtes and summer meetings of the Mothers’ Union.