Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

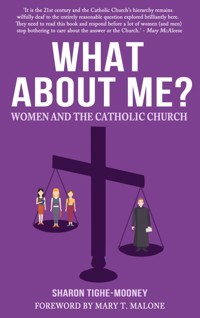

- One woman's investigation of the role of women in the Christian Church since its inception, as she counters the Roman Catholic church's argument for excluding them from the priesthood - Details the gradual exclusion of women from positions of power as the Roman Catholic Church evolved. - Accessible account from the viewpoint of an ordinary woman in the Church. - Cover quotes from Mary McAleese, Fr. Tony Flannery and Mary T. Malone. What About Me? Women and the Catholic Church is an exploration by an ordinary woman, born into the Catholic faith of the arguments given to exclude her from ministry. Using her research skills, Sharon examines the New Testament, Christian writings and Papal documents. It is a personal quest to shed light on the story of women in the Christian movement from its earliest days to the present. The objective of the book is to explore, inform, speculate and question and it should appeal to a general audience. The context of the book is the 2010 move by Pope Benedict XVI to elevate the 'crime' of ordaining women to Catholic ministry and the subsequent censoring of religious personnel who questioned this edict. This book details a quest to find out where the strong antipathy towards women in the Roman Catholic Church's institutional mindset comes from.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 296

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Text: Sharon Tighe-Mooney, 2018

© Foreword: Mary T. Malone, 2018

ISBN: 978 1 78117 540 8

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 541 5

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 542 2

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

For Liam and Luke,

with love and gratitude.

I’d rather live my life as if there is a God

and die to find out there isn’t,

than live my life as if there isn’t

and die to find out there is.

Contents

The Major Eras of Christianity

Foreword

Introduction

The Early Christian Movement

How the Gospels Came About

‘The Jesus Movement’

The Early Church

No Women Allowed

The Chosen Ones: Twelve Male Apostles

After Jesus: Apostolic Succession

Simon Peter, First Witness and Bishop of Rome

All About the Man

We Cannot Ordain Women: An Overview of the Topic

Representation and Nuptial Imagery

Ordination Then and Now

What About the Women?

‘In the Image of God He Created Them’

Women in the Gospels

Women in the Letters of St Paul

The Fall of Women in the Catholic Church

The Church Fathers

Mary and Mary Magdalene

St Paul and Women’s Silence

The Celibate Man versus the Carnal Woman

Jesus and St Paul on Celibacy, Sexuality and Marriage

The Drive for Celibacy

The Final Elimination

Dilemmas and Contradictions

The Might of Tradition

‘All of You Are One’

Conflict, Censure and Pope Francis

Conclusion

Endnotes

Bibliography

About the Author

About the Publisher

The Major Eras of Christianity

1st–2nd century – New Testament times

2nd–6th century – Hellenistic, Patristic model

3rd–4th century – Medieval Latin Catholic model (finalised 11th–15th century)

16th century – Protestant Reformation model

17th–19th century – Enlightenment model

20th–21st century – Postmodern, Ecumenical model1

Foreword

What I liked immediately about this book was its straightforward, clear and explicit title: What About Me?Women and the Catholic Church. The question of women haunts the Catholic Church and has done so for centuries, but, despite mountains of papal encyclicals, the Church is no closer to peaceful co-existence with women.

It was Bernard Lonergan, the great Canadian Jesuit theologian, who suggested that the most radical thing a person could do was to name the obvious. This is what this book sets out to do without excuse or prevarication, and the author, Sharon Tighe-Mooney, delivers to a superlative degree what she promises. The Catholic Church is entirely male dominant in its leaders, its teachers, its hierarchical clergy structure, its liturgy, its language and its exclusively male-metaphored God. We women are so accustomed to it that we barely notice it and we continue the daily task of claiming our personhood and naming our God in the most toxic of circumstances.

It is noticeable that in the past few years the Catholic Church itself has officially ceased to attempt an explanation of this situation and has retreated to the least convincing position, that of proclaiming its authority to decide such issues. The most recent such proclamation came from Pope Francis, who, when queried about the priestly ordination of women, replied, ‘that door is closed’.

Attempts at a theological explanation of the status of women as nonentities in the Catholic Church go back centuries, but a series of recent statements continues to attempt such an explanation. In 1943 Pope Pius XII suggested that women and men were ‘absolutely equal’ coram deo, in the sight of God, but in the sight of men, however, this was not the case as women and men had been assigned specific roles in the ‘order of creation’ and women would always be in a position of subordination to men. In the 1970s Paul VI brought further confusion to the issue. On the one hand he made Teresa of Ávila and Catherine of Siena Doctors of the Church, thus contradicting the apostle Paul’s dictum that women could not teach in the Church. On the other hand, he issued what became the definitive statement against the ordination of women, Inter Insigniores. This document was greeted so negatively by theologians worldwide that it struck a blow at further attempts at theological explanations about why women had to occupy an inferior status in the Church.

Pope John Paul II contributed two more definitive statements to the subject. They were ‘ontological complementarity’ and the ‘genius of femininity’. Each of these deals with the fundamentally auxiliary position of women in the Catholic Church, and bring us to the nub of the issue. In one sense, the question of ordination has been a good distraction for the Catholic Church. It has drawn attention away from the essence of the issue about women, and that is femaleness, the full female humanity and personhood of women.

For the Catholic Church femaleness is at the opposite pole to divinity. The Church is happy to talk about femininity, the ‘nice’ cultural attributes of women. It can even speak of femininity in God who is kind and merciful and displays other womanly secondary attributes. But femaleness is another matter.

What a relief then to turn to the writings of Christian women, specifically the medieval women mystics, who proclaimed with absolute confidence, ‘My real me is God’ and who celebrated their relationship of intimacy and even identity with God. At one of the most misogynistic periods in the history of Christianity, these women found their own appropriate way of speaking to and of God. And this fundamentally is the meaning of mysticism, which has been the woman’s way of bypassing male mediation and naming and claiming their own God.

There are two kinds of Christians, two kinds of Catholics, women Catholics and men Catholics. The story of male Christianity has been the absolutely predominant version of Christianity and Catholicism available to us. Now, thanks to women such as Sharon Tighe-Mooney, we are beginning to hear the women’s story of Christianity, of Catholicism and, even more importantly, of God.

Mary T. Malone

Wexford, 2018

Introduction

I was rather taken aback by the Vatican’s 2010 decision, under the papacy of Benedict XVI (2005–13), to upgrade the ‘sin’ of ordaining a woman. Considering the context at the time – with worldwide revelations about the child abuse scandal, the vast scale of cover-up and secrecy, and the hostile stance taken towards victims – this was, to my mind, a rather strange move. In addition, given that women are forbidden from ministry in the Catholic Church, as well as being personally unaware of any specific public call for the ordination of women, I was puzzled by the timing and curious about what the move actually meant for women. First and foremost, it suggested that the Church meant business on this issue. There was to be no more discussion, and all pertinent people, such as seminarians, ordinands, clergy and theologians in Catholic institutions, are now obliged to take an oath affirming this position, among others, on Church teachings.

To close down all avenues of discussion, as John Paul II (1978–2005) had similarly done, seemed a defensive action. For me, it prompted the question of what it was that the men of the Church feared. Why make something that was already sinful and forbidden a more serious ‘sin’? I was also curious to see what it said about the Church’s attitude to women. Why at that time? What was the motivation, and more important, what were the implications?

I should point out that I felt seriously offended by this action. I have never understood why, as the Church teaches, the Holy Spirit would not call women to serve as ordained ministers when clearly women are and always have been called to serve God: within the restrictions placed upon them by the men of the Church, that is. I should also point out that while many women feel the same as I do about this, many other women do not. In other words, just as is the case for men, all women do not think and feel the same way about everything. Just as with men, they have different opinions, experiences and motivations. This is something I think needs to be said because, when reading material issued by the institutional Church, I have been struck by the recurring perspective on women, which is, first, that the value of women is completely bound up with their role as mothers; and second, the assumption that all women are the same.

I realised that I wanted to explore the story of women in the Christian movement and find the origin of such strongly held negative views about women. The Catholic Church is influential in many parts of the world. Many women live their lives according to its edicts while being denied access to its organisational ranks. In my view, while gender inequality continues to exist in organised religions, the barrier to full participation for women in all aspects of society will continue. This might seem like a weighty claim, but if we look at the aspirational aspects of many religions, which encourage people to respect and value one another, the secondary position of women in these religious structures undermines that message. Moreover, the scriptures have been used again and again to position women as inferior beings. In other words, we are supposed not only to believe, but also to accept, that while humans are equal in the eyes of God, this does not mean that women have equal access to priestly ministry. So the teaching that we are all one in Christ Jesus has restrictions. In my view, while this dichotomous worldview persists, violence against or abuse of anyone perceived as ‘other’, in this case, women, is implicitly condoned.

My own background is Catholic and I am a long-time member of a church choir. I believe in God and in the survival of the soul or spirit after death. I do not believe that God is sexist, racist or homophobic. Nor do I believe that one faith system is necessarily ‘better’ than another. I have at times found church rituals to be somewhat comforting or soothing. I have heard wonderfully affirming words and ideas expressed from the altar to help people cope with life, its trials and its tribulations. At the same time, I have also been seriously irritated and offended at the views delivered from the pulpit. In my case, the idea of a group of mostly elderly white men imposing their views and their will on women’s lives and decisions, without any consultation or even regard for women, gradually began to rankle. How had it come to pass that our lives could be shaped and formulated by celibate men living in an autonomous enclave in Rome? Furthermore, what kind of God would divinely ordain the superiority and authority of one Christian over another?

My journey towards questioning the tenets of Catholicism began as a series of unrelated events. Many will recall collections for ‘black babies’ from their schooldays. We were told that these babies were doomed to spend eternity in Limbo unless saved by missionaries. I was stunned by this revelation. How could innocent babies, because of where they happened to be born, be subject to such a fate? I simply could not accept this as being true. Questioning such edicts, however, was simply not done at the time, as my experience of Church teaching in convent school and in the Church itself was one based on the notion of sin and guilt, on the imposition of rules and with the expectation of unquestioning obedience. As a result, I felt as an adult that I knew very little about Catholicism and its history. Sharing a house with Protestant and Presbyterian friends many years later made it clear to me how little I knew about my faith in contrast to my housemates’ impressive knowledge of theirs.

As the years went by, I found myself continuously irritated at having to deal with everything from a male point of view. I also had difficulty with the diametrically opposed edict of, on the one hand, placing responsibility for the perpetuation of the faith on Catholic women, and, on the other, the complete exclusion of women’s voices in decision-making in the Church. Where, as a woman, was I supposed to fit in? How, as a woman, was I supposed to identify with such a male-centred Church? Moreover, how can a Church that is identified as a loving Church be so disdainful about half its membership because of their gender?

Some years later I happened to be studying the fiction of the Irish writer Kate O’Brien (1897–1974) for my doctorate, and what really interested me was her exploration of the impact that Catholic Church edicts had on the way her female characters thought, behaved and conducted their lives. During my research, I came across a copy of Mary McAleese’s Reconciled Being: Love in Chaos. In her book, McAleese mentions that while she was writing a speech to be delivered in a church the following day, it occurred to her that she was probably the first woman to stand in the pulpit without a tin of polish and a duster in her hand! The image stuck in my mind and I began to question the extent of the role that the Catholic Church had played in the experiences and lives of women. This, in turn, led me into an exploration of the representation of women in the Bible and in Christian writings. To a large extent, the motive for writing this book was to find out what I wanted to know myself.

The many questions I had about women’s lack of place in the Roman Catholic Church ultimately boiled down to two: first, why do Catholic women not have a role in the organisational model of their own Church? And second, why is the institutional Church so opposed to the idea of female ministry that the Vatican is prepared to dismiss, excommunicate and censure their own personnel for attempting to discuss the topic? In the quest for knowledge and enlightenment, I have been helped greatly by the many excellent books published on the subject by historians and theologians, whose work has contributed to and assisted this personal exploration immensely. The research I have drawn from most especially includes Women and Christianity, in three volumes, by Mary T. Malone; The Gospel According to Woman by Karen Armstrong; Eunuchs for Heaven by Uta Ranke-Heinemann; and The Ordination of Women in the Catholic Church by John Wijngaards. Mary T. Malone is a former Professor of Theology at the Toronto School of Theology, now living in Ireland. Karen Armstrong is a former religious sister and has written many books on faith and the major religions. Uta Ranke-Heinemann is a convert to Catholicism and the daughter of the former President of West Germany, Gustav Heinemann (1969–74). She was a classmate of Pope Benedict XVI’s at the University of Munich in the early 1950s. In 1970 she became the first woman in the world to hold a chair of Catholic theology at the University of Essen, which she lost in 1987, however, after denying the Virgin Birth. She has been one of the most outspoken critics of Pope John Paul II. John Wijngaards is a former Vicar General of the Mill Hill Missionaries and founder of the Wijngaards Institute for Catholic Research, based in England. In 1998 he resigned from his priestly ministry in protest against Pope John Paul II’s decrees Ordinatio Sacerdotalis and Ad Tuendam Fidem, which forbade further discussion about the topic of women priests in the Catholic Church.

A word about how sources have been noted might be useful. A frequently used source is the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The Catechism was commissioned by the Council of Trent (1545–63) and published in 1566 for use by priests. It was reissued by Pope John Paul II in 1994, and this is the edition used throughout. In the introductory letter of the Catechism, Pope John Paul II described the work as ‘a statement of the Church’s faith and of catholic doctrine, attested to or illumined by Sacred Scripture, the Apostolic Tradition and the Church’s Magisterium’.1 In other words, the statements or teachings are, he said, supported by the Bible, the apostles, their successors and the Magisterium or teaching authority of the Church. All paragraphs in the Catechism are numbered, and so the usual manner of referencing is used, which is to cite the particular paragraph referred to rather than the page number. All Bible references are taken from The HarperCollins Study Bible, unless otherwise stated. Quotations are referenced in endnotes and all sources are listed in the bibliography by author surname in alphabetical order.

Ancient sources are a little different. The individual gospels are first divided into chapters and then into sections or verses. A quotation from the Gospel of Mark in the Bible will therefore look like this: (Mark 2.14), that is, the Gospel of Mark, chapter two, verse fourteen; and Mark 2.14–16 is the Gospel of Mark, chapter two, verses fourteen to sixteen. In addition, for reasons of brevity, the various gospels, such as the Gospel of Mark, for example, are on occasion referred to as ‘Mark’ or ‘Mark’s gospel’. Similarly, the term, ‘Church’, will be used hereafter to refer to the Roman Catholic Institutional Church Organisation. Dates following the names of popes and archbishops relate to their years in office; other dates following individuals’ names relate to birth and death years.

I am conscious that the subject matter is an area of deep personal significance to many people. Moreover, there is little doubt about the importance of faith in the lives of millions of people around the world. While many may not agree with what I have to say, the aim of this book is not to convince, but rather to discuss. Like most things in life, there are no simple, clear-cut answers. Rather, what I offer here is one perspective, based on the research undertaken to find some answers to my questions; questions that many historians and theologians have also posed and investigated. What interests me is how those questions have been answered by the Vatican, and how such answers resonate with an ordinary lay person, such as myself, reading the material for themselves. My hope is that readers will find my discoveries interesting and thought-provoking.

1

The Early Christian Movement

How the Gospels Came About

Whether we are aware of it or not, the way we think and behave in the West has been framed by a Christian heritage. That heritage includes a specific worldview of women’s ‘nature’ and role in society. While there have been important cultural advances for women in this regard, the one institution that has not altered its perception of women to any great degree is the Roman Catholic Church. The Bible, as well as Christian texts and history, were written by men, about men and for a male audience. Moreover, these works have been interpreted and taught by men. Thus women are presented from a male perspective. Of course, women are and always have been present in all aspects of societal, cultural and religious development, but their thoughts, opinions and actions are not recorded in the same way as those of men. As a result, it can be difficult to ‘read’ their story, a position of which the teaching authority of the Church has taken advantage, despite the proliferation of scholarly work since the 1960s addressing this discrepancy.

The Church argues that they follow the example of Jesus, who chose men for his apostolic team, to maintain a male-only ministry. Evidence to support this teaching is gleaned from the scriptures, particularly the New Testament, wherein the life, teachings, death and resurrection of Jesus are recorded. Thus, because the scriptures are used by the teaching authority of the Catholic Church to position women as secondary and to exclude them from ministry in the Catholic Church, we need to know something about the origins of the Gospels and the other books in the New Testament to understand the position it takes.1 The difficulty with what is recorded in the New Testament is that Jesus himself did not write anything down, and neither did his immediate group of followers. His words were passed on by word of mouth. While oral traditions preserve key features, they are liable to suffer amendments, additions, omissions and rewordings, and as a result, are essentially fluid.

It was at least twenty years after Jesus’ death before any written evidence about him was composed. When accounts of him were eventually written, they were aimed at a range of audiences, written to address contemporary issues and consequently moulded to fit particular circumstances.

The earliest written accounts we have are the letters of St Paul (c. ad 10–62), the most prominent missionary of the early Church and a convert to the Christian movement following his vision on the road to Damascus. These letters are, to a large extent, answers to questions posed by the communities Paul had established, about the young, burgeoning faith and how to practise it. It is important to bear in mind that the early movement, which could be described as a splinter group from Judaism, meant that the boundary between Christian and Jew remained indistinct for quite some time.

The long period of time, perhaps as much as a hundred years, over which the accounts of Jesus were written down, explains the various anomalies we shall see between accounts of events in the four gospels and Acts of the Apostles. Moreover, written material discovered in two caches in the twentieth century suggest that diversity of religious belief and practice was a feature of the early Christian movement as it sought to establish itself.

In 1945 a large hoard of written material from the early centuries of the Christian movement was discovered in a jar in Egypt. Some fifty-two texts survive, including gospels, prayers and secret books of wisdom. They have been dated to around ad 350–400 and drew on material from, it is argued, the first to third centuries. These are known as the Gnostic Gospels or the Nag Hammadi Codices, the latter name relating to where they were discovered. These texts, on the one hand, emphasised salvation through secret knowledge, and on the other, contained similar as well as contrasting ideas and debates about Jesus, scripture and salvation to that found in the Gospels. For example, one sect, the Gnostics, argued that it was the knowledge (gnosis) of Jesus’ message, rather than his death and crucifixion, that saved humanity. However, they believed that this secret knowledge was revealed to only a few.

The second discovery was the Dead Sea Scrolls, found in a number of caves along the west bank of the Dead Sea and the River Jordan, between 1946/7 and 1956. These have a much earlier provenance – c. 250 bc to ad 100 – and contain elements of the Hebrew Scriptures, commentary on the Old Testament and accounts of daily life in a Jewish community. According to Mark Humphries in Early Christianity this material also includes stories about a number of people claiming messianic status.2

These two discoveries indicate that a myriad of sources about Jesus and other religious-type figures, such as prophets and teachers, were in circulation up to at least the fourth century. These sources, coupled with the concern for ‘false teachers’ that St Paul writes about in his letters, suggest that Jesus’ status as Messiah had to be fought for. As a result, the question of deciding which written records were ‘authentic’ accounts of Jesus’ life and teachings was an inevitable step in the attempt to establish some form of unity in the burgeoning Christian movement. In The Gnostic Gospels, Elaine Pagels relates that Bishop Irenaeus of Lyons (178–200) ‘insisted that all churches throughout the world must agree on all vital points of doctrine’.3 Thus, Pagels explains, texts that did not share the same point of view as that decided upon by the Church were to be excluded; in other words, deemed heretical. The chosen works, it was decided, should represent certain truths that were thought to be inspired by God through the Holy Spirit.

The gradual compilation of the definitive list of books to be accepted by all Christians took over 300 years of protracted discussion. Eventually, uniformity of doctrine, ritual, canon (from the ancient Greek word for a rule or measure) and structure was established. In this way, scattered Christian groups gradually became more unified or catholic (which means universal) as accepted interpretations, doctrines and rituals were implemented.

As a result of this process, many written accounts of Jesus’ life, work and death, and accounts attributed to some apostles and disciples, were excluded from the canon. The omitted material includes gospels attributed to Mary Magdalene, Thomas, Philip and James, though some of these were included in the New Testament in some churches for a time. Additionally, there were texts, Pagels writes, that questioned whether all suffering, labour and death derive from human sin, or whether Christ’s resurrection should be taken as symbolic rather than literal. Others celebrated the divine feminine as well as masculine. Some had Jesus speak of illusion and enlightenment rather than of sin and repentance, while others depicted him as not being distinct from humanity, but with the self and the divine as being identical. The implication was that to know God is to be, or to share in, the divine. In addition, some intimated that Jesus had come as a guide and facilitator for spiritual understanding, and not to save us from sin.

In any case, by the end of the fourth century ad twenty-seven texts from the myriad of written material available had been collated as the official New Testament canon. These are: the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John (the word gospel comes from the Greek word for good news or message); twenty-one letters; the Revelation of John, which is a catastrophic vision of the future; and Acts of the Apostles, an account of the deeds of Jesus’ immediate successors. Thus the written Christian tradition is a selection of texts chosen from a range of material that presented various accounts, as well as interpretations, of the life, death and teachings of Jesus.

As a result of the range of available sources, there are anomalies in the four gospel accounts. For example, the descriptions of Jesus’ origins vary from account to account. We know that he was born during the reign of King Herod, who died in 4 bc, and that he was crucified at some time between ad 26 and 29. Nothing is known about his childhood and early manhood, and the story of the census obliging the family to travel to Bethlehem at the time of his birth is recounted only in the Gospel of Luke. Mark describes Jesus as a carpenter: ‘Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon, and are not his sisters here with us?’ (Mark 6.1–4). However, Matthew describes him as the son of a carpenter: ‘Is not this the carpenter’s son? Is not his mother called Mary? And are not his brothers James and Joseph and Simon and Judas? And are not all his sisters with us?’ (Matthew 13.55–56). Whatever his occupation, it seems clear that Jesus was part of a large family, a fact to bear in mind later when discussing Our Lady.

The notion of Jesus’ three-year ministry is based on the Gospel of John, as his account mentions three Passovers (John 2.13; 6.3; 19.31). According to the other gospels, however, his ministry could have been as short as one year. The reasons for his arrest also vary among the accounts, although all agree that the resurrection happened on the third day. In addition, the sequence of events is different from one gospel to the next.

The reasons for such variations arise from the circumstances in which the four gospels were written: from the sources the authors used and the cultural context of the times. Matthew’s and Luke’s accounts are based on Mark’s gospel, with all three appearing to share similar sources. As a result, they are called the synoptic gospels, from the Greek word, synoptikos, which means ‘from the same point of view’. John’s gospel is a later work that scholars argue could have been composed as much as fifty years after Mark’s account. Most scholars agree that the Gospel of Mark was written first, though this is still debated. While the gospel is attributed to ‘Mark’, the author is unknown and it is thought to have been written between ad 69 and ad 75, some forty years after the death of Jesus, and long after the time of the apostles.

In From Jesus to Christianity, L. Michael White describes the background to the four accounts. Mark’s gospel suggests an audience with a strong Jewish identity and the context of the gospel was the wiping out of the Jewish revolt against Roman rule and the destruction of their Temple. The Jews believed that after this suffering, and according to prophecies in Jewish scriptures, Christ would return to deliver them from their enemies. Their disappointment at this proving not to be the case, coupled with the successful suppression of the revolt by the Romans, seriously eroded their faith. They began to question whether Jesus really was the Messiah. The Gospel of Mark is a response to that uncertainty, as the author seeks to reassure his audience. To do so, he has to reappraise the belief in Christ’s return in the light of what has occurred. As a result, the focus in this account is on the portrayal of a human, suffering Jesus, rather than a being of power, so as to align the story with the contemporary situation of his followers.

The next gospel, the Gospel of Matthew, written in Greek, is attributed to Matthew (or Levi), a tax collector and disciple of Jesus, but again, the actual author is unknown. It was not unusual at the time to attribute a work to an authoritative or well-known figure, to lend the work authenticity and gravitas. Matthew’s gospel is thought to have been written around ad 80–90 and is also concerned with the role of the Jews in the new Christian movement, though Christian elements are more apparent here than in Mark’s account. The focus in this text is on Jesus as a compassionate, healing Messiah. Also included are a number of instructions for living a good life and many warnings about the consequences of not doing so.

The Gospel of Luke and Acts of the Apostles are now thought to have been originally a single text. While they are attributed to Luke, the physician and travelling companion of St Paul, the author is unknown. The date of composition is debated, with a range from ad 90–100/110 likely, and the accounts appear to have been written for a Gentile rather than a Jewish audience, in contrast to the earlier gospels. Both works are dedicated to Theophilus, a name in Greek that is a combination of two words, meaning ‘God’ and ‘love’, and so this can be interpreted as being a dedication to those who love God. At the time dedicating a work was a common practice when writing the biography of an important person. There are new episodes introduced in Luke’s gospel, such as the angel visiting Mary and the parables of the Prodigal Son and the Good Samaritan. Also evident is an emerging sense of self-definition as Christians, a term that was just beginning to be coined by Gentile followers of the Jesus movement. Luke’s account, therefore, appears to be an attempt to flesh out the story of Jesus, while Acts describes the early days of establishing Christian communities, in particular Paul’s role in that story.

In the final, or latest, account of Jesus, in the Gospel of John, the Jewish worldview is absent. In fact, there is a strong anti-Jewish rhetoric present, from where, it can be surmised, the anti-Jewish stance taken by the Church up to recent times emerged as being divinely sanctioned. In this account, the otherworldly or heavenly aspect of Jesus is premised, and he speaks in long monologues rather than parables. In addition, Jesus’ humanity is downplayed, and there is much less of a focus on him as a suffering, crucified Messiah, or indeed on his life and work. Rather, his divinity is emphasised. Scholars believe that this gospel was composed during different periods and by different authors, with the last piece being written at any time between ad 95 and ad 120. The account appears to reflect the situation of an early Christian group attempting to break away from its Jewish origins and justifying that parting. Thus the intention of this account appears to be the encouragement of Christians in their growing sense of self-definition.

The gospels are, therefore, attempts to tell the story of Jesus for a particular audience in a particular context. We need to bear in mind that each writer had a particular purpose when writing their account of the life of Jesus. Additionally, there was a wide range of stories and materials to choose from when compiling these accounts. So, as the gospels were written anywhere between forty and ninety years after the death of Jesus, they are written reflections on his life, as well as expressions of faith, rather than accurate historical accounts.

‘The Jesus Movement’

The brief overview of the various gospels reflects what L. Michael White describes as ‘the changing social location of the Jesus movement’.4 In other words, there is initially a strong Jewish identity within the movement that grew up around Jesus and for quite some time after his death, that eventually moves away from that heritage towards a new self-defining one, that of Christian. Although, the ‘Jesus movement’ can be described as a sect originating within Judaism, Mark Humphries argues that the situation is more complex and ‘that there is a problem with seeing Judaism as some sort of fixed religious system from which Christianity departed’.5 Rather, the boundaries between Judaism and Christianity were indistinct as both were evolving belief systems; Christianity as a new religion and Judaism in the wake of the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem. Moreover, as White writes: ‘Jesus did not come as the founder of a new religion, and yet a new religion, Christianity, was founded in his name or, more precisely, in his memory.’6 This new religion, however, took many centuries to evolve.

While the idea of a straightforward, unbroken, unified system of belief from the time of Jesus was my experience of taught religion, the evolving development of the religious movement offers quite a different picture. As the gospels and St Paul’s letters suggest, the early movement consisted of widely scattered groups with diverse cultural heritages, practising varying interpretations of Jesus’ teachings and often situated in a hostile world. It is clear too from historical sources that the ‘Jesus movement’ was radical for its time, although any group that posed a threat to the occupying Roman army was at risk from prosecution. This is borne out by the sentence of crucifixion passed on its leader and the persecution of Jesus’ followers, as well as accounts of the sporadic but persistent persecution of Christians in the early centuries of the movement. It was, therefore, a courageous act to become a follower of this new religion.