Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

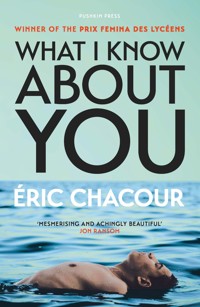

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'A mesmerizing and achingly beautiful novel that will linger in your memory indefinitely' Jan Ransom, author of The Whale Tatto 'Impressive... It is rare to read such a masterful, thrilling debut' L'Express 'A debut that reads like a classic' Le Figaro ______A heartbreaking tale of impossible love in late-twentieth century Egypt. Cairo, 1980s. Tarek's whole life is laid out for him. A doctor like his father, he has taken over the family medical practice, married his childhood sweetheart and is well respected in society. When he opens a clinic in a disadvantaged area of the city, he meets Ali, a young man who is free from the societal pressures that govern Tarek's life. This chance encounter will change everything, throwing Tarek's marriage, career and his entire existence into question. From bustling Cairo to the harsh winters of Montréeacute;al, from the reign of Nasser to the dawn of a new century, Tarek wanders and reminisces. Meanwhile, thousands of miles away, someone is compiling the chapters of his story . . .

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 294

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Éric Chacour was born in Montreal to Egyptian parents, and has shared his life between France and Quebec. A graduate in applied economics and international relations, he now works in the financial sector. What I Know About You is his first novel.

Pablo Strauss’s recent translations of fiction from Quebec include The Second Substance, Aquariums, Fauna and The Dishwasher. He is a three-time finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award for translation. Pablo grew up in Victoria, BC, and has lived in Quebec City for two decades.

PRAISE FOR WHAT I KNOW ABOUT YOU

Winner of the French Booksellers’ Prize 2024

Winner of the Prix Femina des Lycéens 2023

Winner of the Prix des 5 Continents de la Francophonie 2024

Winner of the Bourse de la Découverte Fondation Pierre de Monaco 2023

Winner of the Prix Première Plume 2023

Winner of the Prix des Libraires en Seine 2024

Winner of the Prix du Club des irrésistibles 2024

Winner of the Prix Talents/Cultura 2023

Winner of the Prix du CALQ 2024

Winner of the Prix littéraire Evok 2024

Shortlisted for the Prix Femina 2023

Shortlisted for the Prix Renaudot 2023

Shortlisted for the Prix du Roman Fnac 2023

Shortlisted for the Quebec Booksellers’ Prize 2024

‘Magic … intimate and majestic’ Jean-Baptiste Andrea, winner of the Prix Goncourt 2023

‘A debut that reads like a classic’ Le Figaro

‘Impressive … A masterful, thrilling debut’ L’Express

‘A delicate, sensual, political debut’ Libération

‘Magnificent’ Le Parisien

‘One of the best novels of recent years’ Fugues

ÉRIC CHACOUR

TRANSLATED BY PABLO STRAUSS

Pushkin Press

A Gallic Book

This book is supported by the Institut français (Royaume-Uni) as part of the Burgess programme.

First published in Canada as Ce que je sais de toi by Éditions Alto

Copyright © Éric Chacour and Éditions Alto, 2023

This edition is published by arrangement with Éditions Alto in conjunction with its duly appointed agents Books And More Agency #BAM, Paris, France. All rights reserved.

English translation copyright © Pablo Strauss, 2024

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Gallic Books, Hamilton House, Mabledon Place, London WC1H 9BD

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781805333951

Typeset in Minion by Andy Barr

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI, Croydon (CR0 4YY)

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

For the ones who taught me to love Egypt.

For the women.

YOU

1

Cairo, 1961

‘What kind of car do you want when you grow up?’

He’d simply asked a question, but you hadn’t yet learned to be wary of simple questions. You were twelve, your sister ten, walking with your father along the bank of the Nile through Zamalek’s residential section. Swept along by the boisterous procession of traffic, your gaze wandered to the lotus-shaped spire of the Cairo Tower that had recently sprung up. The tallest in all of Africa, people said with pride. And built by a Melkite, too!

Your sister, Nesrine, hadn’t waited for your answer.

‘That one, Baba. The big red one over there.’

‘What about you, Tarek?’

It wasn’t something you had ever thought about.

‘How about … a donkey?’ You felt a need to justify yourself. ‘Not so loud.’

Your father’s forced laugh made it clear that your answer was beneath consideration. Or was he trying to convince himself that you were only kidding? Nesrine teased loose a lock of her dark hair and curled it around her index finger, a habit of hers when at a loss for words. Clearly convinced that if she pestered him enough she would find herself behind the wheel of a convertible that very afternoon, she said it again, ratcheting up the enthusiasm.

‘The red one, Baba! With the roof that opens!’

Your father looked at you, still waiting for your answer. Just to make him happy, you chose one at random.

‘I’d take that black one, over there. The one stopped at the corner.’

First your father cleared his throat, then he proceeded to explain.

‘Good choice. A fine American car: a Cadillac. You know they’re expensive, right? You’ll need a good job. Engineer or doctor?’

He was talking to you without looking at you, focused on the pipe he had just placed between his lips. He began by sucking in air through the empty pipe, a routine at once mysterious and habitual. Satisfied with the airflow, he pulled out the pouch of tobacco whose smell was so familiar you couldn’t say whether you liked it or not. He filled the bowl, easing his index finger in to arrange the dried leaves, and then painstakingly tamped it down. Each step of this exacting operation was calibrated to yield the right amount of time to think. When he put his pipe back in his mouth to make sure it drew correctly, you knew your time to answer was running out. His clicking lighter rang out like a warning bell. In the smoke of his first puffs, you delivered a half-hearted answer.

‘Doctor, I guess … ’

He remained still a moment, as if considering a newly tabled offer, then answered gravely.

‘Good choice, son. Good choice.’

It was your default choice. You had no idea what engineers did. But that didn’t matter. Your father’s son would be a doctor, just like him. There was no room for argument. Held between the fingers that would one day teach you your profession, the pipe tamper smothered the embers of your conversation. While your father relit his pipe, you imagined putting on his white lab coat, the one he wore on the ground floor of your villa in Dokki where he saw his patients. You were of an age to have no life plans beyond what others devised for you. Was it really just a matter of age, though?

Your walk proceeded in silence. Each of you seemed absorbed in your thoughts. Once all the tobacco was gone, your father checked his pocket watch. It was inscribed with his initials. Yours, too, as it happened. It was time to go home. The watch always read time to go home once all the tobacco had been smoked. Your father’s pocket watch and pipe were impeccably synchronised.

That evening you announced it to your mother. You would be a doctor when you grew up, you told her flatly, as you might share some innocuous piece of news. She was as thrilled as if you’d presented her a completed medical degree, first-class honours. Nasser was remaking Egypt into the greatest country in the world, and your mother had decided you would be its leading physician. A little earlier, Nesrine had made you promise you’d buy her a red convertible.

You were twelve. From that day on you would be wary of simple questions.

2

You had no sense when life would begin in earnest. As a child you were a brilliant student. Everyone said your good grades would serve you well later in life. So life would start later, it seemed. Of the succession of moments that made up your life to that point, few traces remain. Lost are the names of those who wore out their backs carrying you around on their shoulders, unnoticed the hours that went into cooking your favourite dish. What you remember are the minor details: how you laughed at Nesrine because she couldn’t pronounce the Arabic word for pyramid; how you ate frescas on the beach, molasses from the round wafers staining your bathing suits; how you drew pictures with your fingers on the windows that fogged up when Fatheya, your family servant, cooked.

You would stare at the adults, study their body language, inflection and appearance. From time to time, as if called on to speak by some natural authority, one of them would tell the latest funny story they had heard. Then the listeners’ eyes were riveted on the speaker; transformed by this attention, his voice changed, he moved in time with the story and a palpable tension filled the room. You were enthralled by the effect on the audience, a crowd suddenly breathing as one to the rhythm of the storyteller, who only then began to speak more quickly, gathering momentum in his lead-up to the punchline that all had been waiting for. And as one they would respond with a deep, loud burst of laughter that poured forth spontaneously yet in perfect unison.

The men laughed. But what made them laugh? You had no idea. Indecipherable innuendos, impossible exaggerations, unknown words, conspiratorial winks. The mothers’ scowls reminding them that there were children present were met with the blithe confidence that they were too young to understand. You, for one, were too young to understand. This language seemed to belong to the adult world, an undiscovered country. Did one simply wash up on those faraway shores one day, scarcely aware of what was happening – all because you had let yourself drift too far from childhood? Or were these foreign lands, colonised through suffering? Could adulthood remain forever terra incognita? Would the day come when you laughed like them?

The men’s presence electrified Nesrine. She would interrupt their discussions to ask the meaning of a word or answer the most rhetorical of questions. She didn’t get their jokes any more than you did, but she still added her childish laughter to the general chorus. The mere idea of laughing with the others was all it took to get her going. Wasn’t she adorable?

So life would start later. The here and now was not life but something else: a waiting, a respite, perhaps a drawn-out preparation, but for what? More precisely, what were you being prepared for? You had always preferred the company of adults to children your own age. You were in awe of people who never hesitated. The ones whose every action seemed to confirm their grasp on the whole and entire truth. The ones who could with equal aplomb criticise a president, a law or a soccer team.

*

The ones who could, with a snap of their fingers, answer the thorniest of questions: Palestine, the Muslim Brotherhood, the Aswan Dam, the nationalisations. So that was adulthood, stamping out doubt in every shape and form.

One day it would dawn on you that there were few real adults in the world. That no one ever truly gets over their original fears, adolescent complexes, unfulfilled need to take revenge for their first humiliations. If we still find ourselves surprised when someone we know reacts immaturely, it is naive. There are no childish adults, just children who have reached an age where doubt becomes a source of shame. Children who begin to conform to expectations, stop questioning authority, make confident statements without a quiver of doubt, grow intolerant of difference. Children with raspy voices, white hair, a weakness for alcohol. Years later you would learn to flee such people, at any cost. But back then they fascinated you.

3

Cairo, 1974

Fathers are born to disappear; your own died in his sleep one night. In his bed, like Nasser, just when everyone was beginning to think he was immortal. Your mother didn’t realise until the next morning. She rarely woke up before him. Believing he must still be sleeping next to her, she hadn’t dared rouse him. His face in death was as rigidly impassive as the one he’d worn in life. There was no reason to suspect he had crossed the threshold. She glanced at her watch. It was after 6 a.m. How strange that he had not woken up at 5:20, per his custom. At first, she’d worried he would blame her for waking him. Maybe he just needed a little more sleep than usual? Who was she to know what was best for her husband, who was a doctor after all? She waited a while longer. When still he made no sign of getting up, she worried instead that she’d be blamed for letting him sleep. She made some gentle sounds, to no avail. Now sure that she’d be found at fault no matter what she did, she decided to give him a shake. Against all odds, this time he did not blame her for anything at all.

The news didn’t reach you right away. You had just driven off towards Mokattam, the plateau in Cairo’s far eastern reaches where you were having a clinic built. You’d taken a day off to oversee the work. Scarcely had you got out of your car when a young boy ran over to you.

‘Dr Tarek! Dr Tarek! Your father, Dr Thomas, is dead! You have to go home right away!’

You would have suspected a bad joke had he not said your name and your father’s. You tried asking questions, but his shrugs made it clear that he knew nothing beyond the message he had been sent to deliver. You pulled a few coins from your pocket to thank him before sending him on his way. At the sight of the money, a grin replaced the solemn countenance he had put on for the occasion. You got back on the road, more in shock than grief at the news that had yet to sink in. You rushed to get back to your family.

You came in through the clinic where your father would never again practise, not yet trying to understand the implications of this seismic shift, and took the stairs four at a time to reach your mother’s side. You found her sitting in the living room with your aunt Lola. The scene resembled a rehearsal for her new role as widow, held before an audience of one. Visibly thrilled to have front-row seats for your mother’s investiture, your aunt showed her appreciation with effusive sobs. You felt almost like you were interrupting.

Sensing your confused presence in the doorway, your mother beckoned you in. Her bracelets jingled with impatience. When you reached her, she stood up, took you in her arms and offered a commonplace – ‘He didn’t suffer’ – in answer to a question that you hadn’t asked. Her face was suitably drawn, her hair tied neatly in place. Since she was a good head shorter than you, you had to hunch your back awkwardly to hold her. For a few seconds you remained still, not entirely sure who was consoling whom. Then she freed herself from your grip and instructed you to go find your sister.

When she saw you walk into the kitchen, Nesrine began sobbing uncontrollably, to the servant’s chagrin. For hours now, Fatheya had been conjuring remedies to keep Nesrine from breaking down, from hot drinks to firm embraces and divine beseeching; your arrival was a gust of wind assailing this carefully constructed house of cards. Fatheya gave you an angry look that softened when it struck her that your sister’s grief was yours as well. She walked over and looked at you, whispering, ‘My dear.’ She had a thousand and one ways of saying my dear. This one meant stay strong. She then nodded her head, to show you that she had a lot to do, and left the two of you alone.

Nesrine’s distraught face made her look younger than her twenty-three years. She reminded you of the adolescent girl you used to take for feteer in Zamalek, back when she’d tell you all her problems. You never found one that couldn’t be dissolved in the honey of those sweets. Perhaps they were the very thing to bring her comfort at that moment. You wouldn’t tell Nesrine where you were taking her, nor would she try to guess; you just had to get both of you away from this house in mourning. She’d crack a smile when she recognised the café storefront. The two of you would think as one, without speaking a single word. She could watch the baker work the dough, sending it spinning through the air above the marble countertop, his expert hand movements multiplied in the mirrors behind him. It would be no more than a misdemeanour against the regime of your shared grief.

You soon chased that thought from your mind. It was hard, under the circumstances, to imagine telling your mother you were heading out for a stroll. None of us is ever wholly what society expects us to be. At that moment, you two were meant to put on dignified faces to evoke respect and compassion. Certainly the picture did not include pastry crumbs in the corners of your mouths, to be wiped off with the haste of greedy children.

Feeling the full weight of your twenty-five years, you sat next to your sister. The chair was still warm from Fatheya’s presence.

‘You okay?’

In answer she showed you her kohl-streaked cheeks. How could she be okay? She smiled. That was enough.

You had been graced with a moment of calm before the coming storm. News of your father’s death would quickly raise a crowd, like sand swept up into the air by the khamaseen of spring. You were too young to have seen Cairo’s Levantine community in its heyday, but it was still very much a city within a city. And such a community, close-knit in times of joy and grief, would keenly feel the death of one of its eminent physicians. Your people, known as Shawam in Arabic, were Christians of various eastern confessions come to Egypt by way of Syria, Jordan or Palestine. They formed the core of your father’s practice and your family’s social life. Even after generations on the banks of the Nile, many were more fluent in French than in the Arabic they used only when necessary. They were seen as foreigners at worst, ‘Egyptianised’ at best, a view they did little to dispel.

You were raised in a self-contained and increasingly anachronistic bubble. Your bourgeois world recalled a progressive, cosmopolitan Egypt where diverse communities lived side by side. The Levantines saw themselves in the European education of the Greeks, Italians and French. Like the Armenians, they had known the ferrous tang of blood preceding exile. This common ground made for strong ties. Your father’s family was among those who had fled Damascus during the massacres of 1860. All that remained of that homeland was his first name, a tribute to St Thomas Gate, where his ancestors had lived, a few pieces of heirloom jewellery and the pocket watch that never left his side. In the hope that you would one day pass on this heritage to your children, he told you and your sister stories of past times: how successive waves of newcomers spurred the intellectual rebirth of the land that welcomed them, and how during the British ‘veiled protectorate’ your people rose to eminence in culture, industry and trade.

While your father’s words proclaimed his pride in his origins and gratitude towards his family’s adopted nation, notes of melancholy seeped through in his inflection. He knew how much water had passed under the Qasr al-Nil Bridge since those days. Another Egypt had come into being. Galvanised by Nasserian patriotism and dreams of grandeur, it was intent on reclaiming its Arab and Muslim identity. This new Egypt was determined not to lose its elite. Then came the Suez Crisis, the nationalisations, confiscations, emigrations – so many rude awakenings for the Shawam who saw themselves as a bridge spanning East and West.

You remembered a time when not one day went by without some friend announcing their departure for France or Lebanon, Australia or Canada. With no violence but that of inner turmoil, those who left resigned themselves to leaving behind the land they had so dearly loved, where they had expected to be buried one day. You were among the few thousand who stayed. The ones who refused to abandon a country that had turned its back on you, intent on maintaining the illusion of the good life, in their homes and their churches, in the French-language schools they sent their children to and the Greek Catholic cemetery in Old Cairo, where your father would soon be laid to rest.

The next day a crowd gathered at your home in Dokki. One of Fatheya’s cousins had come to help manage the procession of mourners your mother greeted with a dignity befitting the solemn occasion. She received the timed visits of those brought to your front door by a mix of propriety and voyeurism. They came with shop-worn phrases of condolence and memories of your father dusted off for the occasion. But all the while they were silently sounding the depths of your despondency. They scrutinised the lines fatigue had traced under your eyes, how your voices quivered when someone spoke the name of the deceased. Then they went off on their way, with a lingering taste of pistachio sweets and duty fulfilled. For some, it seemed, death was life’s greatest entertainment.

This was your first intimate acquaintance with bereavement. You came to know the diffuse feeling of being outside yourself, almost dissociated from your own body, as if the mind refused to inflict on the body a pain it could never withstand. You were watching yourself from a distance, replaying each moment: learning of your father’s death, welcoming guests, trying to soothe your mother. You could hear each word you said ring out as if spoken by someone else. And you could see yourself alongside Nesrine, whose tears flowed freely while your eyes stayed dry.

It took almost a full week, but then, one night in the solitude of your room, you felt your first tears welling up. From that point on, all you would ever know about your father would reside in memory. But that wasn’t the source of the waves of vertigo coursing through you. You were seized by a new distress, the sensation of a responsibility akin to being gripped in a vice. You felt it pressing on your chest. The social obligations that filled the days following your father’s death had given you a clear sense of the position he held in the community, the one that would by extension and inheritance now fall to you. In fact, the tears you were crying at that moment were mainly for your own fate. You were an impostor waiting in the wings to dispossess your father of everything, down to the very tears you owed him.

Fuelled by superstition and exhaustion, you imagined your father in the room with you: an invisible, omniscient presence watching your movements and deciphering your thoughts. The moment you felt him nearby, every detail came flooding back: the tone of his parsimonious speech, the expressiveness of his brow, the smell of his tobacco burning in his pipe, the outbursts and cheers that could erupt only during his bridge game, and his ability to count every card played in the round. There was the sure hand with which he had taught you to palpate patients’ bodies, track the signs of incipient illness, anticipate the clinical questions that often did little more than confirm the intuition formed at the first auscultation. There was the firm look that had the authority to contain your mother’s anger. You briefly wondered whether it was this last element that you would miss the most.

These visions of your father in tableaux of everyday life had a calming effect. His return to his rightful place at the centre of your grief had smothered the flames of guilt that threatened to consume you. Your body settled back into its habitual rhythms. You had thought of him; you had cried. No matter the order in which these two acts had occurred, you had done what a grieving son must. You were physically exhausted but would have been hard-pressed to say why. You wondered how long it would take your mind to extract each of these memories. Before an answer came, you fell asleep.

The following weeks engulfed you in duties and decisions. Your mother threw herself into her new life with painstaking devotion. She accepted the signs of fatigue – what could be more appropriate under the circumstances? – but made sure they could not be construed as giving up. A certain tearfulness was tolerable, despondency under no circumstances pardonable. She traced a fine line between these states and always managed to be on the right side of it. And while everyone praised your mother’s strength of character, few noticed Fatheya, who went about selflessly and discreetly fulfilling her employer’s many orders.

It must be said that Fatheya was not, strictly speaking, her given name. At birth, her parents had named her Nesrine. Your mother soon saw that two Nesrines in the house would sow confusion. And of course it would never do for her progeny to share even a first name with her maid. But when Fatheya turned out to be a hard worker and a quick learner, and was found by careful counting after each service not to covet the family silver, your mother decided not to hold Nesrine/Fatheya’s prospective usurpation of her daughter’s name against her. She simply, by fiat, gave her maid a new name. Since Fatheya had not been consulted on her original given name, what right had she to protest the arbitrary imposition of this new one? This onomastic redemption only encouraged Fatheya to work harder to satisfy her employer. And at that moment in time, her job was to turn her transition to widowhood into a series of sparkling social occasions.

And how could you blame your mother? You knew full well that her new position was far from enviable. Even a half-century after Huda Sha’arawi cast her veil and mantle into the sea off Alexandria, the right of unmarried women to manage their own lives and administrative existence was a faraway dream. In cases like your mother’s, a son was a precious asset. It fell to you to handle the red tape around your father’s death, on top of your work taking over his practice. Almost all his patients stayed on with you, despite the great difference in age and reputation.

You continued performing the procedures taught at the prestigious Qasr al-Ayni medical school, which your father had imbued with meaning and substance. Along with technique, he had taught you intuition, to the extent that such things can be taught. How to consider not just a disease but also the person suffering from it. How to listen for not just a heartbeat but also its reason for beating. He was sparing with praise, but you learned to decipher the signs of approval and sometimes even pride that slipped through. After you started off as his assistant, he let you take the lead on more and more patient visits. Sometimes, in front of others, he would even ask your opinion on specific cases or stress the value of your input in his diagnosis. This made you self-conscious until you realised it was his way of positioning you as heir to his knowledge. Now that he was gone, you would have to build your own reputation on the foundation he had laid.

The clinic closed for only two days. It was important to get the practice running again as soon as possible. You had to honour the appointments made prior to his death, and you worked meticulously to decipher your father’s handwritten notes in each patient file before they came to you for treatment.

Nesrine got into the habit of coming to see you in your ground-floor office. She knew you’d be working late. You liked when she came to find you there; it made for a pleasant break in the final hours of your busy days. Though she claimed to be there to help, her good intentions never extended beyond the jobs you found for her. After a time, she would get up and make you a ‘white coffee’ – hot water with a few drops of orange blossom extract and just the right amount of sugar. Night would settle in. The two of you would discuss your childhood memories, or your parents. Sometimes the future, often the past. Nesrine claimed that orange blossom was good for the memory. You never pointed out that she hadn’t done any of the jobs she’d ostensibly come to help with. It didn’t matter in the end. Her presence sweetened your evenings.

One day you had the bright idea of giving her a cat. She named it Tarboosh. There was no shortage of stray cats on the streets of Cairo, but this one wasn’t yet weaned, and looked abandoned. Knowing that your mother would look askance on this new family member’s humble roots, you and your sister made up a nobler origin story. Officially, Tarboosh was part of a litter put up for adoption by a friend of yours. Nesrine made a wonderful surrogate mother. She fed Tarboosh with pipettes from your supply closet and petted him more than any cat in Cairo. As time passed, Nesrine kept up her habit of visiting your office, though more and more of her attention was directed towards her beloved cat. This left you free to work on your medical records, while still enjoying her company and of course her white coffees.

4

Cairo, 1981

A Coptic patriarch in the time of the Fatimid Caliphate: you could almost picture him with a fulsome beard, dark vestment, cope and amice. You could go back one thousand years, you recalled, and still find the Coptic patriarchs wearing the same long beards. The story went on. The Caliph challenged the patriarch to prove that his religion was true. ‘Was it not written, truly I tell you, if you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can say to this mountain, “Move from here to there,” and it will move?’ ‘Well,’ said the Caliph, ‘let’s see if it works on Mokattam Mountain!’ If it failed, the Coptic people would be annihilated.

The story may have taken place ten centuries earlier, but the tension in the speaker’s voice that day was tangible. You loved listening to the people of Mokattam recounting the legends in which they took such pride. Though their settings were now familiar, you had never before heard these stories.

The old cleric was crestfallen. After three days of fasting and prayer, he had a vision of the Virgin Mary. She urged him to go to the marketplace, where a tanner named Simon, who had only one good eye, his left, would come to his aid.

Just one eye? Ever the good doctor, you wondered what had caused this loss of vision. As it transpired, an impure thought had afflicted the shoemaker at the sight of a customer’s foot; in an act of penitence, he gouged out his own eye. Even before this compelling evidence of his piety, you couldn’t help imagining the scene, and the woman whose sandals would go unrepaired due to this act of self-mutilation. But none of that was the point of the story. For this prudish craftsman was also a miracle worker, a skill that would soon be put to good use. With a few incantations, Mokattam Mountain rose up under the incredulous eyes of the Caliph, who was forced to recognise the truth of Christian scripture.

A silence fell; they were awaiting your reaction. You contrived to look impressed by the ending. You understood how the Copts of Egypt cherished this miracle. In the belief that they owed their very survival to it, they were still here a thousand years later, clinging to the land that today resembled an open-air dump. Everything had changed a few years earlier, when Cairo’s governor ordered that the entire city’s trash be dumped there. Trucks laden with refuse to thrice their normal height now came to dump their loads. An entire economy arose around the dumps, communities of pickers called zabbaleen, who lived off sorting, reselling and recycling. They created all manner of things out of nothing, ingeniously transforming soda cans into handbags and even the inhospitable walls of their mountain into a place of worship: for years now they’d been carving the Church of Saint Simon the Tanner right out of the mountainside.

Those who cannot move mountains can at least build a clinic, you told yourself. You kept to yourself the belief that it would do more than a church to help the needy people of Mokattam. In the seven years since your clinic had opened, much had changed. First, a roof had to be built over the original building’s four bare walls. What began as a makeshift infirmary now had mostly potable running water and electricity. For years, your weakest patients sat waiting on the folding chairs you carried out at the start of each shift and lined up along the outside wall. Then, you had a waiting room built next to your consulting room. The work had begun last month, and you were thrilled with each visible advance. You even sometimes lent a hand, under the amused stares of the locals, who had never seen a doctor carry bricks. Was that any job for a man of your profession? What physician worth their salt would have time for such lowly tasks? Luckily, these naysayers were no hindrance to your reputation, which had now crossed over from the west bank of the Nile.

You had your reputation and knew just how much of it you owed to your father before you. But the idea of caring for patients in Mokattam had been your own. Fearing how your father might react, you had waited months to tell him. Against all odds, he was positive: pleased to see that medicine was occupying you in your spare time as well, he had simply made sure your new activity wouldn’t interfere with your work in the Dokki clinic. After an initial aversion to what she perceived as a waste of time, your mother had fallen into line. There was no shame in learning your craft working with patients of humble station. In case of medical error, the stakes would be much lower.

A noisy, haphazard queue formed each time you opened your clinic, a gathering of the infirm and ailing, toothless seniors, sickly children, and a handful of women who came back, week