18,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In the late twentieth century, disasters seemed like distant happenings in countries far away from the prosperous West. But today they are 'coming home' with a vengeance. From global warming to migration crises, from assaults on democracy to Covid-19 and the fall-out of war in Ukraine - the West is in the grip of multiple, overlapping crises that keep its populations in a state of perpetual fear and distraction. Disasters should be awakening us to the need to reform our disaster-producing system. Yet instead, as David Keen shows in this disturbing and original book, they are routinely being exploited for political as well as economic gain. A number of crises, whether slow-burning or sudden, are not only reinforcing each other but also bolstering the toxic politics that helped to generate them. One key problem here is the use of emergencies to vilify those who are trying to relieve them or to highlight their root causes. Unless these voices and alternative perspectives find a way to break through, we risk being locked into a system of emergency politics that is self-reinforcing rather than self-correcting - and that routinely manufactures its own legitimacy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 568

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Acknowledgements

1 Disasters Coming Home

Longer-Term Disasters

A System of Disasters

Bread and Circuses

Magical Thinking and Self-Reinforcing Systems

North, South, East, West

Notes

2 Lessons from ‘Far Away’

Beneficiaries

Democracy’s Fragile Protection

Legitimizing Disaster

Dangerous Explanations

Uneven Costs

Conclusion

Notes

3 A Self-Reinforcing System?

A Focus on Consequences

Debt and De-Democratization

Three Dreams

Conclusion

Notes

4 Emergency Politics

Identifying Enemies

Charisma and Self-Reinforcing Cruelty

The Politics of Distraction

Breaking Bad

Conclusion

Notes

5 Hostile Environments

The Functions of Disaster

Deterrence

Putting on a show

Deterrence and Theatre at the Mexican Border

Promoting Suffering

When Helping People is Wrong

The Expanding Enemy

Conclusion

Notes

6 Welcoming Infection

Embracing Disaster

Public Health and the Economy

Conclusion

Notes

7 Magical Thinking

Trump

Popular Affinity for Fictional Realities

Elite Magical Thinking

Violence Coming Home

In Search of a ‘Golden Age’

The Magical and the Mundane

Blue Magic?

Whose

Magical Thinking?

Conclusion

Notes

8 Policing Delusions

Defending the Big Lie

Magic and Intimidation in the ‘War on Terror’

Conclusion

Notes

9 Action as Propaganda

Five Types

Reproducing the enemy

Creating inhuman conditions

Blaming the victim

Undermining the idea of human rights

Making predictions come true

Conclusion

Notes

10 Choosing Disaster

The Politics of the ‘Lesser Evil’

Problems with the ‘lesser evil’ argument

The Road to Hell

Conclusion

Notes

11 Home to Roost

Notes

References

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Tables

Chapter 5

Table 1. Recipient countries’ incentives in relation to human rights situation in ...

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

vi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

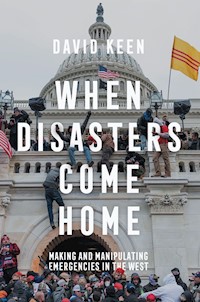

When Disasters Come Home

Making and Manipulating Emergencies in the West

David Keen

polity

Copyright Page

Copyright © David Keen 2023

The right of David Keen to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Permission was granted by Disasters (Wiley) to re-use material previously published as David Keen, ‘Does democracy protect? The United Kingdom, the United States, and Covid-19’ (volume 45, issue S1, December 2021). This material appears in Chapter 6.

First published in 2023 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5062-3 (hardback)

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5063-0 (paperback)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022945381

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Acknowledgements

Space is tight and I’ll keep this short. But I am hugely grateful to friends, colleagues and family for innumerable suggestions and enormous patience. Special mention for my sister Helen for her kindness and encouragement. Aunty Ann has also been a great support – not least in chivvying me gently so that I (almost) met my deadlines. I’d also like to say a huge thank you to Louise Knight and Inès Boxman for their faith in this project and for their great patience and support through the writing process. Thanks to Steve Leard for a great cover design and to all at Polity for their editing and proofreading. Ruben Andersson has been a hugely important source of support, encouragement and intellectual input. Mark Duffield has been an inspiration here and at various points in my life. My students and colleagues at LSE have also engaged very interestingly with this topic. I’d also like to thank Maya, as well as Emma, Pascale and Heather in my writers’ group. Among those who have been especially helpful with their feedback are Mats Berdal, Ali Ali, Thomas Brodie, David Dwan, Gopal Sreenivasan, Clare Fox-Ruhs and Martin Ruhs. Other supportive friends have been too numerous to mention individually but special thanks to Harti, Ade, Cindy, Cristina, Sam, Gunwoo, Chandima, Georgia, Nira, Thomas B., Jenny, Huw, David, Gordon, Jennifer, James, Angela, Freda, Haro, Eric, Rob, Patricia, Klaus, Martin C, Paul, Andreas and the St Antony’s football community. A special thank you, too, to my daughter for her charm, humour and forbearance, making the writing process much happier. And most of all, I am hugely grateful to Vivian for her help with the manuscript, for putting up with all papers and the hours, and above all for keeping such a resolute faith in me. I dedicate this book to her: hers is the kind of kindness and sweetness of soul that might yet rescue us from all of this!

1Disasters Coming Home

Just down the muddy road from a famine ‘relief’ centre with one of the highest death rates ever recorded anywhere in the world,1 a northern Sudanese trader was hosting an elaborate feast. ‘God sent me the famine’, he told me before noting the large profits he’d made from transporting high-priced commercial grain to the Dinka people of southern Sudan, who were visibly emaciated, mostly unable to afford whatever grain had arrived in their vicinity, and subject to enslavement, hyper-exploitation and robbery on their northward journey. This was 1988 and northern Sudanese merchants were also involved in funding militias who were creating famine through mass theft of the Dinka’s cattle.

Behind the scenes, the Sudanese government was desperate to access oil in the south by forcibly ejecting the Dinka from areas where rebels were opposing the extraction of oil. While encouraging the militia raiding through arms and impunity, the Khartoum government was also preventing the delivery of famine relief to the areas where it was most needed, instead forcing aid agencies to collude in forcible depopulation by focusing their aid only on the edge of the oil-zone. To be in an environment where famine was being actively created was deeply shocking.

It became increasingly clear that a range of important benefits were being anticipated and often actually extracted from disaster – and Sudan was hardly an isolated example of this. In the 1990s and 2000s, a growing body of research suggested that disasters in a great many poorer countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America were not simply a source of great suffering but also an opportunity. A dangerous and shifting mix of warlords, militias, traders, governments and rebels were routinely instrumental in creating disasters from which many key players were benefiting. That finding emerged strongly from my own investigations – in Sudan and also in Sierra Leone, Guatemala, former Yugoslavia, Sri Lanka, Iraq and on the Turkey–Syria border – as well as from a wide range of research by others.2 Alongside the lesson that disasters have beneficiaries and functions, a related lesson was also becoming increasingly clear: that attempts to relieve these disasters were themselves being routinely undermined precisely by those who were benefiting or seeking to benefit.3

Of course, the 1980s was also the era of Bob Geldof and Live Aid, and this is what got me interested in famine in the first place. Critics of humanitarianism later came to speak of a ‘white saviour complex’, and there was a slightly unfortunate turn of phrase in the Live Aid anthem, ‘Do they know it’s Christmas?’, which advised its listeners ‘Tonight thank God it’s them instead of you.’ In the UK, the suffering certainly felt a long way away. Today, the world seems radically transformed in many respects, so that thanking God for this exemption seems increasingly ill-advised.

While Sudan and the breakaway state of South Sudan are still suffering from wars and famines, there has been substantial growth in many parts of Africa as well as some patchy progress towards democracy. Ethiopia made substantial progress in tackling famine (though the current war/famine in Tigray is a huge step backwards). In Asia, nations that were previously labelled as ‘underdeveloped’, most obviously India and China, have come surging through (despite major political and economic problems) to the status of major powers in the world economy.

Among Bob Geldof’s ‘saviours’, meanwhile, the situation has deteriorated in significant respects. A wide range of situations suggest that disasters, and indeed the active manipulation of disasters, are actually ‘coming home’ to Western democracies. Before considering how and why this is playing out, I should clarify what I mean by ‘disaster’.

The Oxford Dictionary of English defines a disaster as ‘a sudden accident or natural catastrophe that causes great damage or loss of life’.4 But while this may sound reasonable, it misses the possibility that a disaster may be very extended and it also tends to locate disasters within a framework of ‘nature’ that risks playing down human responsibility. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines a disaster as ‘a sudden calamitous event bringing great damage, loss, or destruction’, but again we should note that not all disasters are ‘sudden’. In the context of conflict-related disasters in particular, Mark Duffield has written insightfully about ‘permanent emergencies’ – a concept, as we shall see, that applies disturbingly well to the current situation in Western democracies as well as much of the rest of the world. Partly to avoid assuming that disasters are ‘sudden’ or ‘natural’, I use disaster in this book to mean ‘a serious problem occurring over a short or long period of time that causes widespread human, material, economic or environmental loss’.5

Over the last two decades or so, nine high-profile disasters threatening Western democracies stand out (though there are certainly others). Six are relatively specific, involving high-profile events (many quite ‘sudden’), and the other three are slow-burning disasters – the unfolding of deeper underlying processes.

First, then, there has been a significant problem of terrorism along with a complicated political backlash. The devastating attacks of 9/11 severely dented a sense of immunity to disaster that many people in America had previously enjoyed, with fear also reverberating in Europe and elsewhere. After this, there were other major terror attacks, including in Madrid in 2004, London in 2007 and Paris in 2015.6 The threat of terrorism spurred and legitimized a resort to various kinds of emergency powers and increased domestic surveillance, both of which have now become relatively normal in Western democracies.

At the same time, there is convincing evidence that foreign policy in the Middle East, particularly the ‘war on terror’ from 2001, played a significant role in generating many of these terror attacks, so that violence backed by Western governments (and the US in particular) may in this sense be said to have ‘come home’ or even to have ‘come home to roost’. Terrorism has been ‘coming home’ in at least two other senses. First, many jihadist attacks within Western democracies have had a significant home-grown element, with the perpetrators having lived in the West for a long time or even having grown up there (see e.g. Keen, 2006). Second, there has been a generally under-recognized but growing problem of right-wing terrorism perpetrated by white people. Between 2008 and 2017 far-right and white-supremacist movements were responsible for 71 per cent of extremist-related killings in the US (compared to 26 per cent for jihadist extremists).7 The phenomenon need not have come as a revelation: after all, the second worst terror attack on American soil was carried out in Oklahoma City in 1995 by a white American Gulf War veteran, Timothy McVeigh and his associate Terry Nichols. One careful analysis noted that the 9/11 attacks were ‘a gift’ to peddlers of xenophobia and white supremacism, and that the ‘war on terror’ and increased domestic surveillance of Muslims also energized the far right.8 Yet, in 2005 the US Department for Homeland Security had only one analyst working on non-Islamist terrorist threats.9

A second set of disasters increasingly affecting Western democracies has been weather-related. While such disasters have often been assumed to be a phenomenon primarily impacting Asia, Africa and Latin America, any ‘immunity’ among Western democracies is increasingly difficult to discern. We have seen hurricanes and floods wreaking destruction on New Orleans, New York and Puerto Rico, bushfires ripping through California, Australia, Turkey and Greece, and so on. In 2021, floods in Germany, Belgium and several other European countries shocked climate scientists when precipitation records were broken.10 Meanwhile, extreme heatwaves were smashing records across the western United States and Canada. In Colorado in 2021 wildfires were raging in December. Matthew Jones at the University of East Anglia has reported an eightfold increase in forest wildfires in California over the past twenty years, with water scarcer and forests drying out.11 In this rash of extreme weather events, climate change has been an important factor. We also need to look at policies that have helped to produce underlying vulnerabilities to existing weather events. A great deal of literature on disasters makes clear that hazards like extreme weather events or earthquakes translate into disasters via underlying vulnerabilities, so that a smaller earthquake in Haiti for example can cause more damage and more suffering than a bigger earthquake in Chile.12

A third disaster has been financial crisis, notably in 2007–8. The lasting impact of the 2007–8 crisis was exacerbated by policies of austerity. Programmes of ‘structural adjustment’ that had been associated with Africa and Asia and Latin America since the mid-1970s were now penetrating right into the heart of Europe, with Greece the worst affected and Italy, Spain, Portugal and Ireland and many others also suffering significantly. The erosion of sovereignty that many had bemoaned in the context of the Global South became rather clearly a feature of European politics,13 playing a part in the rise of far-right parties like Golden Dawn in Greece.14 The erosion of sovereignty also inserted itself into major American cities, as we shall see. It turned out that capitalism and its debt-collectors did not particularly discriminate between the Global North and the Global South, while debt, de-democratization and disaster proved to be close cousins within Europe and North America just as they had long been within other continents. Financial crisis recurred in the UK in 2022, to give one example, when the Truss government’s planned tax cuts alongside heavy spending on energy subsidies sent financial markets into a tailspin.

A fourth set of disasters impacting Western democracies has been a complex array of humanitarian disasters around migration. These have included mass drowning in the Mediterranean, significant mortality in American deserts adjoining the border with Mexico, and inhuman conditions in camps for migrants in Europe as well as on the US–Mexico border and offshore from the Australian mainland. Then there has been the damage to political culture – hard to quantify but very significant nonetheless – that comes when fundamental human rights such as the right to asylum are not respected, when the ability of aid organizations to offer assistance or to speak about suffering is severely curtailed, and when ‘hostile environments’ are actively created both within Western democracies and on their geographical fringes.

A fifth disaster has been Covid-19. First detected in Wuhan, China, the coronavirus has been wreaking havoc in a number Western democracies as well as many other countries around the world. With Covid, we have seen the extra danger that arises precisely from the assumption that disasters are somebody else’s problem.

A sixth disaster has been the war in Ukraine. (We might consider Ukraine a Western democracy since its government is elected and Ukraine is part of Europe.) The war in Ukraine, which has severely impacted on food supplies to many countries in Africa and the Middle East, is also impacting on democracies further west – for example through the movement of refugees, through rising energy prices, and even through the huge expenditure that some Western democracies (most of all the US) are making on weapons for Ukraine as well as on humanitarian assistance. Then there is the small matter of a possible nuclear war triggered by the tense confrontation between Russia and the NATO allies, at which point disaster would be seen, albeit briefly, to have come home with a vengeance.

Longer-Term Disasters

In addition to the six relatively ‘sudden’ and ‘dramatic’ disasters set out above, we need to consider three underlying disasters impacting strongly on Western democracies. As the book progresses, we will explore some of the ways in which longer-term underlying disasters are feeding shorter-term disasters, and vice versa. Disasters that appear to be sudden have often been the product of longer-term processes.

The first of the underlying disasters impacting on Western democracies (as well as the rest of the world) is an ongoing economic crisis linked to globalization, oligopolization, and automation. Particularly from the 1990s, capital became increasingly unregulated, hyper-mobile and able to search out relatively low-wage and low-regulation environments around the world, as well as boom-environments where pushing out large amounts of capital became (for a while) a kind of self-fulfilling prophesy of quick profits.15 Robert Wade, Professor of Political Economy and Development at the London School of Economics, has noted ‘After the collapse of the Soviet Union around 1990 and the opening to trade of China, India and other large developing countries at around the same time, the global labour force roughly doubled’, thereby greatly weakening the bargaining power of labour and raising the share of profits in world gross domestic product (GDP).16 A set of complex processes, acting together, have tended to marginalize or simply render redundant the labour of millions of workers within Western democracies, though manufacturing output itself has held up much better than most of the traditional industries.17 As some countries have rapidly industrialized, others have suffered partial de-industrialization.18 In the industrial Midwest of the US, scrap metal from devastated industries was literally shipped to China, thanks largely to the migration of jobs (and, incidentally, the cheap rates for ships that were emptied of Chinese products when they arrived in the US).19 Globalization, often envisaged as a kind of ‘export’ of democracy and free markets to the entire world, has had the effect of ‘importing’ into the West some of the chronic precarity and superfluity that has long been fostered in the Global South.

Linked to globalization, and fuelled also by a range of government policies, has been an escalation of inequality (for example in the UK and the US). Between 1978 and 2012, the share of wealth enjoyed by the richest 0.1 per cent of the population in the United States rose from seven per cent to fully 22 per cent, a reversion to the level of inequality that had prevailed before Roosevelt’s New Deal politics emerged in the wake of the 1929 financial crash. The share of wealth enjoyed by the top one per cent of the US population had reached 42% by 2012.20 That inequality has contributed to a vulnerability to disasters – both personal disaster and wider societal disasters – among a vast swathe of the population. Financial crisis in turn fed into underlying structural problems (including through a boost to automation that was reflected, for example, in production recovering more quickly than employment after the 2007–8 crash).

A second underlying crisis is climatological. So called ‘natural disasters’ have never been less natural, and no part of the world is exempt from this existential problem. The number, severity and impact of our current weather-related disasters is increasing significantly in comparison to even the late twentieth century.21 Severe weather-related disasters have increasingly been occurring within temperate as well as tropical zones.22 And future escalations seem certain in the context of global warming and a widely predicted rise in conflict and migration (or at least attempts to migrate). Of course, weather-related disasters are hardly novel and the saying goes that there is nothing new under the sun. But even this phrase takes on new meaning when a drastically thinning ozone layer escalates the impact of the sun itself. At the same time, protection policies make a difference, and the voluntary or enforced neglect of domestic infrastructure has increased vulnerabilities to weather-related (and indeed geological) disasters. We will see this vulnerability in the case of New Orleans. The terrible Greek wildfires of 2021 were made worse by cuts in the firefighters’ budget that had been forced through by EU, European Central Bank and IMF officials in the context of the country’s debt crisis.23

A third underlying disaster has been a political crisis. The precise nature of this crisis depends on who you ask: in fact, one person’s ‘disaster’ is likely to be another person’s ‘solution’. This disparity itself betrays a wider political problem, which is arguably itself a disaster: there has been a shrinking of shared truths and shared political spaces. In this connection, Pankaj Mishra has pointed to ‘a severely diminished respect for the political process itself’.24 Retreating into ‘alternative realities’ has become commonplace, with right-wing populists often leading the way. As this book develops, we will get a better idea of some of the problems growing up around the ‘alternative realities’ that our current political moment has thrown into prominence. In particular, we will see that once a proper analysis of causes and effects has been set aside, relevant belief systems have often been defended through intimidation and even violence.

The rise of right-wing populism has seen a growing intolerance, an increasing resort to emergency powers, and a significant erosion of democratic norms. Major crises in Western democracies have included not only Brexit in the UK and Trump in the US but also the ascendance of openly racist and homophobic political parties in many countries. Again, many of the things that Western publics have tended to associate with ‘faraway’ conflict-affected countries are today increasingly evident within Western democracies that had seemed, at least in the late twentieth century, largely immune. These include the progressive surrender of authority to the executive, assaults on press freedom, denunciations of minorities, constitutional ‘coups’, threats against parliamentarians and judges, the politics of the ‘strongman’, and even the possibility of secession and all the conflict that this tends to bring with it.25 In the US, a country where political crisis has been especially intense, 2020 saw escalating protests against police violence, with the President actively inflaming the underlying rage and racial tensions before going on to incite an attempt to overturn the November presidential elections – an extraordinary blow to democratic norms.

A System of Disasters

A kind of ‘emergency politics’ is significantly shaping many political systems across the world, and Western democracies are far from immune. It may be that globalization is now helping to ‘import’ into Western democracies not only the large-scale superfluousness and precarity afflicting the rest of the world but also some of the emergency politics that many influential actors in the Global South have for some time been fostering and using to distract, absorb and suppress the energies of discontented populations.26

In several countries where I have myself investigated disasters (including Sudan, Sierra Leone and Sri Lanka), a key part of politics has come to be the instrumentalization of disaster and emergency, while a second important part has been the attempt to limit the political fall-out from disaster. This second aim points towards an agenda of legitimizing disaster. This project seems to be becoming more central in many Western democracies, too. Indeed, making, manipulating and legitimizing disasters and ‘emergency’ are habits that appear to be embedding themselves within Western politics.

It would of course be incorrect to suggest that disasters impacting Western democracies are something new. Such a view would require a remarkably short-term memory that took no account of two world wars, of all manner of weather-related disasters and economic catastrophes in the twentieth century and earlier and, indeed, of the way democracy in Germany’s Weimar Republic succumbed to the rise of Nazism and its accompanying horrors. Even in the last decades of the twentieth century, we should not forget the devastation wrought by AIDS, the destruction effected by wars in the former Yugoslavia, the terrorism in Oklahoma, Ireland, Britain and Spain, and so on. I personally remember the feeling in the 1980s that nuclear war was possible and even imminent, so current anxieties on that score are also hardly new.

As a further proviso, we should note that what felt like safety for many people in Western democracies in the later decades of the twentieth century clearly did not feel like safety for many others. Much of the difference depended on race or ethnic identity. In the US from the 1970s millions of people suffered the evolving disaster of mass incarceration, with Black and Hispanic populations disproportionately affected.27

What would perhaps be fair to say, though, is that a period of relative calm and safety for most people in Western democracies since the end of the Second World War has been giving way, in the twenty-first century, to a politics in which making and manipulating disasters has become increasingly common. A proliferating array of disasters are today feeding into each other in ways that are profoundly disturbing and ways that we need to understand much better.

Terrorism, weather-related disasters, financial crisis, humanitarian crises among migrants, Covid, Ukraine, structural economic crisis, climate crisis and political crisis: while the list of crises or disasters now impacting on Western democracies is certainly a long one, we should also notice that these various disasters tend to be treated separately. Quite rightly, there are specialists in each of these topics, specialist journals and specialists specializing in special aspects of each specialism. There are, of course, significant advantages in taking complex problems one at a time. But again, we also need a much better awareness of the ways in which these crises relate to one another. We need to acknowledge the diversity of disasters that are impacting Western democracies as well as the rest of the world. We need to be clear-sighted on which are being hyped and which are being underplayed. And we need to recognize that these crises are strongly feeding into each other in what amounts to a mutually reinforcing system of emergency-and-response, a politics of emergency that tends to feed voraciously off itself.

Bread and Circuses

In this book, I emphasize the salience of a ‘politics of distraction’. Our three underlying disasters are major drivers of many more immediate and apparently sudden disasters but are typically not addressed effectively amid a succession of high-profile responses to the more visible and sudden disasters. Worse, when Western governments respond with a drive for increased ‘security’ – allocating additional resources for the military, building walls, and bolstering abusive governments that offer to cooperate in a ‘war on terror’ or in ‘migration control’ – these responses tend not only to bypass the underlying problems but to exacerbate them.28

One key mechanism here is this shoring up of repressive governments that say they are going to tackle terrorism or migration. A second mechanism is that underlying problems fester and proliferate when high-profile security measures absorb huge amounts of tax revenue. The cost of these various ‘security systems’ is sucking the lifeblood from systems of public health and social security, which in turn feeds back into vulnerability to disaster.

Today’s overlapping disasters offer important opportunities for political manipulation as well as important economic opportunities for the expensive apparatus of deterrence that has been constructed around a variety of much-trumpeted ‘threats’, whether ‘terror’, ‘drugs’ or ‘mass migration’. In effect, a sense of threat is being hitched to policies that generate more suffering – and more ‘threats’. Meanwhile, an emphasis on ‘building walls’ tends dangerously to reinforce a pre-existing sense of ‘immunity’ to collective problems.

Today, we may say that a range of relatively spectacular emergencies like migration crises and terrorism have acquired an important ‘function’ in distracting Western populations from deeper-lying crises that major vested interests would prefer to leave unaddressed or even actively to worsen. As part of this, Western electorates have been invited to ‘buy into’ magical solutions for a range of high-profile crises.

Even the peculiar ‘political emergency’ that was Trump-as-President seems to have served as something of a distraction from the economic and political processes that put him in power in the first place. Today’s proliferating disasters suggest a disturbing relevance for the old saying that grievances can be contained within a policy of ‘bread and circuses’. For disasters themselves – and the trumpeted responses to proclaimed disasters – have become a kind of continuous political ‘theatre’. Like plays, disasters hold the potential to awaken us to important underlying problems but all too often serve to keep us in a state of distraction and morbid entertainment.29

Magical Thinking and Self-Reinforcing Systems

Influenced by colonialism (and in turn helping to shape it), a common way of thinking and writing has been to construct societies outside Europe, Australasia and North America as driven by emotions, passions, irrationality and magical thinking, while Western societies are seen to have embraced science and efficient bureaucratic modes of governance.30 In my own work on disasters in the Global South, I have tried to bring out the very considerable extent to which these ‘far away’ disasters were all too rational, with a range of vested interests helping to drive destructive processes (both from within and outside the disaster-affected countries). Of course, such interests interacted with emotions in complex ways, and I also became interested in, for example, the complex interaction of economic accumulation and shame (or more broadly the interaction of greed and grievance) during the civil war in Sierra Leone.31

A related project, and part of the intention in this book, is to highlight the complex interactions of interests and emotions in relation to disasters unfolding in the Global North. This project invites not only an exploration of the various mundane functions that these disasters may be serving, but also of the extent to which they are being driven by magical thinking, a phenomenon that seems increasingly to be embedding itself in the politics of Western democracies as an integral part of our disaster-producing system. Understanding this is all the more urgent since the fragile protection afforded by democracy would seem to be significantly eroded when popular sentiment is stirred up in ways that promote or even welcome disaster – often through the promotion of beliefs that lack scientific backing.

By ‘magical thinking’, incidentally, I mean the belief that particular events are causally connected, despite the absence of any plausible link between them. The term has been used in different ways by various thinkers, and has been commonly invoked in anthropology.32 Psychoanalytic thinking also rests heavily on a variety of conceptions of the magical, and Freud showed that in mental illness the magical side of human thinking often takes precedence. In The Unconscious, Freud observed that ‘The neurotic turns away from reality because he finds either the whole or parts of it unbearable.’33 In Totem and Taboo, Freud suggested that people with neurosis ‘are only affected by what is thought with intensity and pictured with emotion whereas agreement with external reality is of no importance’.34 The obsessions of neurotics ‘are of an entirely magical character. If they are not charms, they are at all events counter-charms, designed to ward off the expectations of disaster with which the neurosis usually starts.’35 Freud saw a connection between the belief systems of neurotics and those he called ‘primitive’ people ‘who believe they can alter the external world by mere thinking’.36 Yet he also wanted to stress that such a flight from reality among those with neurosis comes at a huge cost in terms of both human suffering and the difficulty of recovering. As psychoanalyst Thomas Ogden explained, ‘magical thinking subverts the opportunity to learn from one’s lived experience with real external objects’.37

In Totem and Taboo, Freud linked ‘magical thought’ with the ‘omnipotence of thought’.38 He saw ‘primitive’ magical belief systems as mirroring the baby’s reaction to its earliest experiences. He noted that a baby may wish for the breast and, if the breast appears, the baby may attribute this to the power of its own thoughts (hence the ‘omnipotence of thought’). But a baby who remains purely in the realm of thought (and forgets, for example, to kick and scream when hungry) might not even survive.39 Freud argued that the temptation to wish away an unpleasant reality and even to construct a new one with our own thoughts is not left behind at this moment when the baby ‘gets real’, but rather is put into a place where a lifelong competition with reality-based thinking can begin.

While we often think of the process of development and modernization as bringing progress and empowerment, Freud portrays this modernization as a kind of disempowerment, at least in terms of how humans experience their own power. Thus, he notes in Totem and Taboo, ‘At the animistic stage men ascribe omnipotence to themselves.’40 This is because, while spirits proliferate, humans think they can influence them. Somewhat similarly, in ‘the religious stage’ humans transfer the sense of omnipotence to the gods ‘but do not seriously abandon it themselves, for they reserve the power of influencing the gods in a variety of ways according to their wishes’.41 In the scientific stage, Freud wrote, omnipotence has been abandoned, and ‘men have acknowledged their smallness and submitted resignedly to death and to the other necessities of nature’.42 Yet that degree of humility and powerlessness is a tough thing to embrace, as Freud well understood. While Freud often tended to push the concept of magical thinking onto others (‘neurotics’, ‘primitives’), it would be more realistic to suggest, particularly in light of Freud’s own account of an increasing sense of impotence as human history unfolded, that magical thinking retains very considerable appeal around the world.

It will be important to keep in mind both the appeal and the drawbacks of magical thinking when we come to consider the role of political delusions in relation to today’s overlapping disasters. At the same time, we should also keep in mind the dangers inherent in pointing the finger at particular beliefs and labelling them as magical thinking or as irrational. How can we know what is delusional and what isn’t? And in pointing the finger at the delusions of others, are we drawing a veil over our own?

As the discussion in the book unfolds, I also draw significantly on the fascinating insights of Hannah Arendt, who serves as an important guide throughout. Indeed, the book is intended – in part – as an exploration of the continuing relevance of Arendt’s work. A German-born Jewish political philosopher who fled from Nazi-occupied France to the United States, Arendt contributed hugely to our understanding of violent propaganda and totalitarian reflexes. She showed how and why a fictional and highly destructive view of the world could become plausible. In so doing, she illuminated the magical thinking that lay close to the malignant heart of fascism.

Of course, there are dangers in importing insights on totalitarianism into non-totalitarian contexts, and nothing in this book is intended in any way to minimize the horrors of the either the Holocaust or the Soviet totalitarianism that Arendt also analysed. But we should remember that Arendt herself was profoundly concerned to understand how a democracy (like the Weimar Republic) could transition to something far more authoritarian and abusive, and some of her later work (for example on the Vietnam War) attempted to understand how democratic governments could embrace mass killing abroad, with damaging consequences also for domestic politics. In a contemporary context where threats to democracy have become significantly more prominent, it is surely no accident that there has been a surge of interest in Arendt’s work. To the extent that contemporary Western democracies are today exhibiting elements of the dangerous, deluded and anti-democratic tendencies that Arendt analysed in The Origins of Totalitarianism, we should not conclude either that a move further in this direction is inevitable or that there is some kind of ‘equivalence’ or even near-equivalence between twentieth-century totalitarianism and what is happening now. But the current moment does feels like a very dangerous one, and one in which we are actually obligated to look at history (including some of its most horrific episodes) in search of lessons and pointers. It also feels like a propitious moment to tap into Arendt’s remarkable wisdom.

We should note, incidentally, that in The Origins of Totalitarianism Arendt did not actually employ the term ‘magical thinking’. Nevertheless, her entire book was a notable exploration of the collective capacity to travel into a world of dangerous delusions. At times, Arendt did use the term ‘wishful thinking’. She noted for example that the ‘non-totalitarian world’ indulges in ‘wishful thinking’ and ‘shirks reality in the face of real insanity’,43 adding that there is a ‘common-sense disinclination to believe the monstrous’.44

As the current book proceeds, we will begin to see how magical (or wishful) thinking and self-interest have proven to be ‘blood brothers’ in fuelling a range of disasters, whether in democratic or undemocratic contexts. Very frequently, politicians have seen some kind of domestic political advantages in stirring up a sense of crisis (a financial crisis, a migration crisis, a political crisis etc.). Some of these crises have been real, some have been underplayed (like climate change), and some have been greatly exaggerated (like the ‘migration crisis’).

Part of magical thinking may be the belief that the preferred way of handling these various emergencies is the only way they can reasonably be handled. This closes down debate and protects unrealistic solutions. Today in Western democracies – as has so often been the case around the world – critics of how these crises are currently being defined and manipulated risk being incorporated into a conveniently expandable category of ‘the enemy’. This process tends to feed the underlying political emergency, which centres to a significant extent on the delegitimizing of dissent and the inability to learn.

As part of our investigation of today’s overlapping disasters, we urgently need to look at the degree to which they – like so many that have unfolded further afield – are being actively manipulated and even, in some cases, manufactured. We need to understand the various political, economic and psychological functions that are being served by this dysfunctional system of emergency-and-response. No doubt the functionality of contemporary disasters in Western democracies is rarely as obvious as it was in the Sudanese famine with which we began our discussion. But the emerging functions of today’s overlapping disasters do need to be examined if we are to provide a proper explanation of why these disasters have taken the form they have, why they have been so severe, and why they have proliferated and persisted. A key part of the problem in Western democracies today, as so often in Sudan and many parts of the Global South, has been that the underlying functions of overlapping disasters have helped to undermine attempts to relieve them, contributing greatly to the ineffective or actively counterproductive nature of responses.

Much of classical thinking about politics and economics suggests self-correcting systems that benefit from in-built ‘checks and balances’: thus a price rise will lead to increased production and hence a fall in prices; a rise in executive power will be reined in by the legislature and the judiciary; an incompetent government will be voted out of power. Of course, such checks and balances have by no means disappeared, and we might take the election of Joe Biden following Trump’s failures with the coronavirus as a reminder that democracy remains a vital defence against disaster. But many of our present-day political dysfunctions do nevertheless have the quality of being self-reinforcing. Indeed, we are confronted with a politics that in many ways is thriving on the very crises it is helping to produce. It’s quite common to hear talk of the ‘slippery slope’ towards totalitarianism, and this expression should itself remind us that some routes to catastrophe have a kind of self-reinforcing quality. Certainly, this ‘slippery’ quality is something that Arendt can help us to understand.

We need to look more closely at blowback, which the Oxford Dictionary of English defines as the ‘unintended and adverse effects of a political action or situation’.45 Unfortunately, rather than changing fundamental policies in response to manifestations of blowback, many politicians in contemporary Western democracies are busy taking advantage of crisis and incorporating blowback into their political strategies. Yet this process – in many ways familiar from the Global South, as we shall see in Chapter 2 – tends only to deepen the underlying political crisis, a vicious circle that we need to find a way to fix.

North, South, East, West

From a Western or Northern perspective, disasters have been rather conveniently and complacently assumed to be far away from Western democracies, and this tendency seems to have been encouraged by assumptions around the otherness of ‘the South’ and ‘the East’. Very often, the prevailing assumption has been that bad things happen only to ‘them’, while Western democracies are involved only in the sense of being potential saviours.

Yet disasters are today ‘coming home’ in at least three senses. First, having for a long time been seen as confined to the Global South (and to some extent the East), disasters, including political disasters, have become an increasingly obvious feature of Western democracies. Second, the nature of Western politics is shifting so that the manipulation of disasters, whether domestic, global or some combination of the two, is becoming (or we might say becoming once again) a key feature. Third, violence perpetrated in ‘far away’ countries (whether in the contemporary era or as part of historical colonialism) is now coming home, or ‘coming home to roost’, as various kinds of blowback or ‘boomerang effects’ take a heavy toll on Western politics and society. Today’s overlapping disasters, not least those impacting the West itself, should be opening our eyes to the major role that Western democracies are playing (and have played in the past) in generating them. The export of disasters in the form of colonialism and modern-day imperialism has found a potent counterpoint not only in blowback but in the instrumentalization of blowback.

In the past, others have remarked on such ‘boomerang’ effects, and it will be helpful to keep their views in mind. The Martinican author and politician Aimé Césaire argued that colonization decivilized and brutalized the colonizer, stirring race hatred at home and propelling the continent of Europe towards ‘savagery’ before eventually, in the ultimate ‘boomerang effect’, finding expression in the racialized violence of Nazism.46 The French philosopher Michel Foucault also referred to colonial models being brought home in a ‘boomerang effect’ or ‘internal colonialism’.47

Arendt also noted ‘the boomerang effect of imperialism upon the homeland’. In the wake of the First World War and a Versailles Treaty that took away Germany’s colonies, Arendt noted, ‘The Central and Eastern European nations, which had no colonial possessions and little hope for overseas expansion, now decided that they “had the same right to expand as other great peoples and that if they were not granted this possibility overseas, [they would] be forced to do it in Europe”’.48 In other words, the persistent allure of empire and expansion found an outlet in the pursuit of Lebensraum in the east. Of course, the primary actor here was Germany.

Today, we must try to understand the contemporary manifestations of such rebound effects, not least when it comes to the lasting effects of colonialism and the more immediate effects of the ‘war on terror’. Both sets of effects have been incorporated into a renewed politics of intolerance within the West.

While it has been common to use European history to interpret and chastise, say, Africa (with its ‘lack of a Weberian state’, its ‘painfully slow progress towards modernization’, and so on), the possibility of learning lessons ‘the other way around’ has been relatively little explored. But this represents a major missed opportunity. ‘What if we posit’, as anthropologists Jean and John Comaroff suggest, ‘that, in the present moment, it is the so-called “Global South” that affords privileged insight into the workings of the world at large?’49 And what if political trends in the old Cold War ‘East’, for example in Poland and Hungary, are also harbingers of a political world to come?

We should note here that terms like ‘North’, ‘South’, ‘East’ and ‘West’ are extremely problematic. There’s a danger that the North/South and East/West binaries will reify and solidify the relevant distinctions, making the categories seem somehow permanently different and irreconcilable as well as homogenous.50 The Comaroffs themselves suggested that there were enclaves of ‘the South’ in ‘the North’ and vice versa,51 and we know that countries like China, Paraguay and Botswana have broken through to a ‘middle-income’ category, sometimes with spectacular success,52 while southern capital now props up or owns signature businesses in Europe and North America.53 Michelle Lazar notes that it’s ‘important to see the “North” and “South” as relational categories, mutually constitutive, and entangled’54 and, of course, a key part of this relationship has been colonialism. Rather than being hamstrung by the limitations of the North/South distinction, a key aim in this book is to move beyond this distinction and to explore some dynamics and dangers that are operating globally.

When it comes to the distinction between ‘East’ and ‘West’, this is hardly definitive either. For one thing, we may observe that countries can move between these categories: it seems to ‘help’ if they embrace the right blend of markets, democracy and pro-US allegiance (as we have seen with Japan and South Korea). In its violent transition from Communism, Yugoslavia’s ambiguous status also blurred the lines. When it collapsed into war in the 1990s, some politicians and commentators concluded that nothing could be done about these ‘ancient ethnic hatreds’, while Balkans expert Susan Woodward suggested that the region was effectively being redefined (with the help of such language) as ‘not Europe’.55 This ‘othering’ manoeuvre may have helped to preserve a sense of immunity in Europe further west, while also discouraging intervention. More generally, Maria Todorova argues that the Balkans has an uneasy status as semi-oriental, a region that is always trying to shed ‘the last residue of an imperial [i.e. Ottoman] legacy’.56 It would seem, too, that old stereotypes about the inherent ‘brutality’ or ‘otherness’ of ‘the East’ are easily revived – and Russia’s vicious war in the Ukraine has given ample encouragement to this reflex.

As the Cold War wound down, references to ‘the East’ became less common. The term was an uncomfortable one in any case, not least in the light of Edward Said’s influential 1978 book Orientalism.57 Yet it is notable that references to ‘the West’ have continued to be absolutely normal58 (and of course ‘the West’ is in the subtitle of the current book).

Again, my intention is not to reify a binary distinction but rather to consider important things that many countries may have in common, across whichever binary divide. One danger in drawing any sharp line between ‘East’ and ‘West’ is that disturbing developments in countries of the old ‘eastern bloc’ (such as Hungary and Poland) will be taken as somehow separate from – and irrelevant to – political trends in democracies in Western Europe and North America.59 Yet, as Anne Applebaum reminds us in her perceptive book Twilight of Democracy, there is nothing particularly ‘Eastern’ or ‘Western’ about the process by which economic crisis, resentment and frustrated ambition has fuelled the rise of right-wing populism.60

More hopefully, a growing number of people are resisting our disaster-producing politics in diverse and creative ways, and again this process has important precedents and parallels in the Global South. As Western populations’ sense of ‘immunity’ diminishes in the context of global heating and Covid-19 in particular, a sense of vulnerability is making many people more open to radical solutions that challenge our disaster-producing politics. But there is also a political backlash against the protesters, a process of delegitimizing protest and painting dissent as extremism. A key risk is that this backlash serves to consolidate our current disaster-producing system.

In Chapter 2 (Lessons from ‘Far Away’), I set out a number of conclusions arising principally from my investigations of disasters around the word, emphasizing the functions of these disasters as well as the degree to which politics has turned on limiting political fall-out from these disasters. The chapter looks at disasters in the Global South as a threat to government legitimacy and it examines the way poor responses to these disasters have been legitimized. It also looks at how disasters have been explained and who bears the costs – and how these considerations shape the future trajectory of disasters.

Chapter 3 (A Self-Reinforcing System?) explores the extent to which emergencies have become a staple of Western politics, justifying a growing resort to various kinds of emergency measures. I argue that today various disasters are tending to reinforce the policies that generated them, so that we risk being caught in a self-reinforcing system rather than a self-correcting one. A key pitfall has been a collective focus on consequences rather than causes.

Chapter 4 (Emergency Politics) looks at how Trump instrumentalized a sense of insecurity and existential threat, and it positions Trump’s politics within Arendt’s wider analysis of the allure of norm-breaking and even cruelty. The chapter goes on to consider the ‘politics of distraction’ within both the US (where Democrats have played their part as well as Republicans) and the UK. It also examines the contribution to emergency politics that has been made by escalating debt, including in municipal governance within the US.

Chapter 5 (Hostile Environments) looks at some of the functions of the human suffering that has accompanied the tightening of migration controls. The chapter shows how European and US ‘outsourcing’ of migration-control has yielded a number of political as well as economic payoffs, even as it has fed into humanitarian disasters and undermined the right to asylum. Meanwhile, the causes of outmigration have been powerfully stoked, not least when deals have been struck with authoritarian regimes and abusive militias from Turkey to Libya and Sudan. Deterring migration – when taken to its logical conclusion – has involved fostering human rights violations both in ‘transit’ countries and in ‘recipient’ countries (as with the so-called ‘hostile environment’ in the UK). The chapter draws on fieldwork in the migrants’ camp in Calais, France, as well as research by many others, to show how suffering among migrants has been artificially created and has served identifiable functions. The chapter also looks at how hostility to migrants/refugees has been extended to those who are trying to help them as well as to others who may be associated with the migrants/refugees in some way; this is another sense in which disaster may plausibly be said to be ‘coming home’.

Chapter 6 (Welcoming Infection) looks at responses to Covid, another disaster ‘coming home’. Focusing particularly on the US and the UK, the chapter asks what has made these countries so vulnerable and why democracy has not offered greater protection. It also asks about the impact of Covid-19 on democracy itself. One major source of vulnerability, it is suggested, is that at key points in the crisis infection itself was reconceptualized as a good thing.

Chapter 7 (Magical Thinking) looks at how our disaster-producing system is being legitimized through the resort to various kinds of magical thinking. The magical thinking that infuses, shapes and legitimizes the current disaster-producing system has important psychological functions even as it also helps to solidify the more prosaic political and economic interests that are bolstering this disaster system. In this chapter, I draw again on Arendt’s work, not least in analysing how patently ludicrous and destructive ideas can acquire considerable appeal and plausibility under particular conditions.

Chapter 8 (Policing Delusions) looks at the defence of magical thinking – often a violent defence – and at how this is feeding our overlapping disasters. The chapter examines this process particularly in relation to the ‘war on terror’.

In Chapter 9 (Action as Propaganda), I argue that what Arendt calls ‘action as propaganda’ – broadly, the use of violent action to make false claims appear more and more true as time goes by – has been an important technique through which our disaster-producing politics has been sustained and legitimized. While not all the elements of ‘action as propaganda’ have been intended or planned from the outset, there are many kinds of violence that have conveniently created legitimacy for themselves, giving little reason to change course.

Chapter 10 (Choosing Disaster) looks at the way disaster-producing policies have been encouraged by particular framings and especially by framing politics as a choice between a ‘lesser evil’ and some allegedly more disastrous alternative. This manoeuvre rests on a number of dubious assumptions. It depends on successfully evoking a sense of (impending) disaster while playing down the abuse of human rights that is involved in ‘averting’ it. It also depends on an underlying ‘science’ or theory that is rarely spelled out with sufficient clarity or scepticism. This takes us back to some of the key points in Chapter 7 as we explore the strange ‘alliance’ that has today been formed by ‘science’, magical thinking and self-interest.

Chapter 11 (Home to Roost) returns to the idea that disasters are ‘coming home’. Within an emerging system of suffering, we may say that disasters are not just coming home but also coming home to roost. ‘Home to Roost’ was the title of an article by Arendt that discussed the domestic impact within the US of the Vietnam War, and some of the dynamics she highlighted remain extremely relevant today. In the context of various kinds of ‘blowback’ from policies that have long contributed to ‘far away’ disasters, a number of democratic leaders, mostly but not exclusively right-wing populists of one kind or another, have been peddling what we might call the wrong solution for the wrong emergency. This reflex has unfolded in the context of underlying economic disasters (and a broader political crisis) that preceded the most prominent right-wing populists and made them possible. To ignore these conditions is again to focus on symptoms rather than underlying problems.

Notes

1

Keen, 1994.

2

See e.g. Africa Watch, 1991; Duffield, 1994a; de Waal, 1997; Kaldor, 1998.

3

E.g. Keen, 1994; Keen, 2008.

4

Oxford Dictionary of English

, 2010, 498.

5

Wikipedia (drawing on aid agency sources). The definition goes on to refer to a situation that exceeds a community’s ability to cope.

6

Other sites of significant terrorist attacks included Germany, Belgium, Norway, Sweden and Canada.

7

Stevenson, 2019.

8

Miller-Idriss, 2021, 56.

9

Stevenson, 2019.

10

E.g. Watts, 2021.

11

Gutiérrez et al., 2021.

12

E.g. Blaikie et al., 2003.

13

E.g. White, 2015a.

14

E.g. Loewenstein, 2017.

15

E.g. McQuarrie, 2017 on the effects on labour; Wade, 2009 on largely unregulated capital movements.

16

Wade, 2009, 1169.

17

On manufacturing output, see for example Lincicome, 2021.

18

Duffield, 2019.

19

McQuarrie, 2017, S135.

20

Saez and Zucman, 2016.

21

E.g. Coronese et al., 2019.

22

Ibid.

23

Varoufakis, 2021.

24

Mishra, 2017, 341.

25

For example, in Spain and the UK.

26

Cf. Duffield, 2019.

27

Alexander, 2019.

28

E.g. Keen and Andersson, 2018.

29

See, notably, Andersson, 2014 and Andersson, 2019.

30

E.g. Said, 1991.

31

Keen, 2005; Keen, 2012.

32

E.g. Evans-Pritchard, 2002.

33

Freud, 1960, 3.

34

Ibid., 86.

35

Ibid., 87.

36

Ibid., 87.

37

Ogden, 2010, 319.

38

Freud, 1960, especially ch. 3 ‘Animism, magic and the omnipotence of thoughts’.

39

See discussion in Favila, 2001.

40

Freud, 1960, 88.

41

Ibid., 88.

42

Ibid.

43

Arendt, 1968, 437.

44

Ibid., 437.

45

Oxford Dictionary of English

, 184.

46

Césaire, 2000, 36.

47

E.g. Graham, 2013.

48

Arendt, 1986, 222–3 (Arendt is quoting from Ernst Hasse’s

Deutsche Politik

); see also Gerwarth and Malinowski, 2009.

49

Comaroff and Comaroff, 2013, 114.

50

E.g. Lazar, 2020.

51

Comaroff and Comaroff, 2013, 12.

52

Haug, 2021.

53

Comaroff and Comaroff, 2013.

54

Lazar, 2020, 6.

55

Woodward, 1995.

56

Todorova, 2009, 13.

57

Said, 1991.

58

Todorova, 2009.

59

Applebaum, 2020, argues convincingly against such a separation.

60

Ibid., 2020.