7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

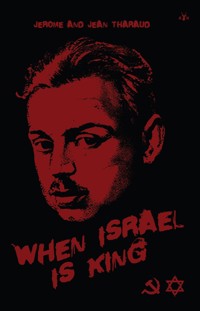

- Herausgeber: Antelope Hill Publishing LLC

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Europe in the twentieth century was a continent of tumult, revolutions, and war.

When Israel Is King focuses in on the events that took place in Hungary in the early part of the century, recounting a swirl of underhanded dealings and political murders as the fortunes of different actors and interests rose and fell, and draws particular attention to one pernicious influence and its role in the chaos.

The factions of Count Tisza, the Kaiser, and even the Soviet Union all made Hungary their contesting ground, a convenient proxy for larger struggles. Above all, however, this narrative brings out the pivotal role played by Israel-that is, the Jewish people and their collective interests. These interests are clearly identified in the Hungarian context, and demonstrated in their desire to bring revolutionary change to the country and create a new Jerusalem. The influence of Israel reaches its zenith with the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic led by Bela Kun, whose demise would bring an end to Israel's designs, at least for the time being.

Written by French brothers and prolific authors Jerome and Jean Tharaud, this updated 1921 English translation of

When Israel Is King is now being made widely available. Antelope Hill Publishing is proud to bring back this foundational work which tells the story of a small but brave land and its struggles, many of which echo ours today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

When Israel Is King

WHEN ISRAEL

IS KING

JEROME AND JEAN THARAUD

A N T E L O P E H I L L P U B L I S H I N G

The content of this work is in the public domain.

First Antelope Hill edition, first printing 2024.

This edition is an edited and reformatted republication of theEnglish edition translated by Lady Whitehead from the Frenchpublished by Robert M. McBride & Company, New York, 1924.

Covert art by Swifty.

Edited by T. Brock.

Layout by Sebastian Durant.

Antelope Hill Publishing | antelopehillpublishing.com

Paperback ISBBN-13: 979-8-89252-007-2

EPUB ISBN-13:979-8-89252-008-9

▬Contents ▬

Introduction

I. The Portrait of Bismarck

II. A Bulwark of the West

III. The House of Orczi

IV. The Murder of Count Tisza

V. An Ambitious Magnate

VI. The End of the Hapsburgs

VII. Karolyi’s Triumph

VIII. Bela Kun

IX. The New Jerusalem

X. In Rural Hungary

XI. The Downfall of the Soviets

XII. A Dialogue Without End

XIII. The Staff of Ahasuerus

▬ Introduction ▬

The present collection is due to the action of certain public-spirited Frenchmen desirous of making better known in English-speaking countries some of their foremost writers of today. They are also anxious to rehabilitate in the minds of those who are not intimately acquainted with the extraordinary richness and variety of modern French literature the foreign reputation of their country which has often suffered in the past from the translations of certain books that have attained a bubble reputation in France and abroad, by reason of the notorious nature of their contents.

All who wish to learn about the real France will find in the present series abundant examples of that sense of life and beauty that distinguishes the French genius, with its unwearying quest of lucidity and proportion (and its balanced belief in the reality of the external and internal world), and above all of that serene seriousness that made possible the miracle of the Marne and the immortal defense of Verdun.

I▬ The Portrait of Bismarck ▬

One day in the autumn of 1899, a young Frenchman arrived at Budapest. No one was waiting for him at the station and he had great difficulty in extricating his luggage and in finding someone to conduct him to the house where he was expected, for, of course, he did not know a single word of Hungarian.

It is always a trying moment when one first arrives in an unknown country to which one has been led by force of circumstances, not by the mere pleasure of traveling, and when a vista of long months to be passed among people and things which chance has chosen for one stretches out ahead. My arrival in Hungary on that autumn afternoon was the crowning point of a long series of years at college, of days without light or liberty or nature, of tedious study, and of examinations without end; and the result of all this had been that one fine day the minister of public instruction sent me as a lecturer on the French language to the Budapest University. The irony of life came home to me in full when, burdened by the weight of my two portmanteaux and laboriously searching for a cab, something within me wondered whether so many hours spent in the Lycée, the Sorbonne, and in boredom, so many regulated efforts directed towards one end spread over so many years, were to culminate in landing me just here and nowhere else, at this railway station, in the center of this town, where I should one day exhibit before a small audience of a few young people the meager stock of knowledge which I had been accumulating for twenty years and which represented approximately my whole capital in life. Standing a little later in the furnished apartment which I at length reached, my luggage at my feet, I considered with comic bitterness those few square yards towards which, ever since I left Paris, and indeed long before that, ever since my childhood, destiny seemed to have impelled me. A bed, a table, two chairs, a sofa covered with American cloth, cracked in many places, a gas pipe hanging from the ceiling, ill lit (for the window looked out upon a court)—that was the sight which met my eyes. Over the bed, hung on the wall, there was a portrait of Bismarck, one of those photogravures after one of Lenbach’s pictures, which at that time an enterprising publisher was spreading broadcast throughout Germany and in all the countries subject to German influence.

It was not the well-known portrait in uniform, with the iron cross and the pointed helmet; neither was it the one in which the artist has concentrated (as in Rembrandt’s fashion) all the light of his canvas on the vast rock-like skull. It was not the Iron Chancellor, nor the soldier, nor the official who was portrayed in this picture, but an old man, clad like one of the middle class, his head surmounted by a broadbrimmed black hat—anEast Prussian country squire, a Bismarck who might always have lived on his own land and passed his days in superintending his domains and collecting his rents. But whether or not anything wonderful had happened in the life of this personage, one felt oneself in the presence of an animal of superb race, with a powerful will firmly established in simple and ancestral ideas.

Should I keep the head of that old country gentleman, with the firm jaw, whose gaze looked out from the deep arch of his bushy eyebrows, looking down upon me from the wall of my room? Should I remain in a perpetual tête-à-tête with that enemy countenance, and have it there morning, noon, and night before my eyes, for all my life? Slowly the light waned around me and the dusk of evening enveloped the room. As darkness fell, the man with the big hat faded away on the wall.

I myself, worn out with the fatigue of unnumbered hours of journeying in a third-class carriage over half of Europe, and washed up at last, like flotsam, at the foot of that portrait, seemed to dissolve in the same darkness. Strange experience! When, a moment later, I had set alight to the gas jet hanging from the ceiling, and the man with the hat reappeared on the wall, I saw him again with pleasure. I was no longer alone in my room. That hostile, hard countenance abruptly recalled to me certain familiar thoughts. Already between him and me a colloquy had been established; his unexpected presence gave a tone and, as it were, a romantic character to my squalid arrival. Certainly Ihad never expected to find a host of such importance in a chance room! Thanks to him I had already experienced an emotion in this strange and mean chamber, which is to say I had begun to live. If I were to remove the picture from its place, I should not only add to the blankness of the wall, but I should rarefy the atmosphere and enlarge the desert around me. Let it be, I thought, we will live together; one never wastes one’s time while in company with such a personality.

So the picture remained, and I must confess that during the four years which I passed in that room we lived very happily together. That portrait became for me a silent and eloquent companion, with whom from time to time, it was good to exchange ideas. I received many a piece of good advice from every line graven on that churlish face, which, at certain hours and under certain plays of light, took on a wonderfully shrewd look and sometimes even an air of melancholy. As a young Frenchman, trained in the ideas which were current with us at the end of the last century, I had arrived there full of the most immature political and social views; but under that stern look, certain naivetes were no longer permitted! I found myself there under the eyes of a judge and of a severe counsellor. When my thoughts floated idly on nothing in particular, I would suddenly become conscious of the clear eyes gazing at me from under the black hat. Then my vagabond spirit, which was always pursuing some romantic chimera, would return to the straight path of reality. And even without my realizing it, during the long, silent, and melancholy hours of exile, that glance reacted upon me, penetrated my inward consciousness, and helped me to see the vanity of the ideas which, in a student’s lodging between the Seine and the Luxembourg, might well exercise an irresistible attraction, but which were out of place here, in the presence of that redoubtable stranger. My severe companion rescued me from the tyranny which books always exercise over the brain of a youth of twenty years (especially when, as in my case, he lived in great solitude), and taught me, without any words, the supreme power of experience and fact. For four years, I was conscious of that face, now grave, now ironic, considering the young Frenchman lost in Central Europe, reading or writing at his plain deal table. For four years that impassive face played the part of a sheepdog about my thoughts, keeping them well grouped together and preventing them from straying hither and thither. And when, after so many days passed in his company, I left Budapest and that room, where nothing had been changed since my arrival, my last look was on Bismarck’s portrait which had received me there, certainly not a friendly glance, but assuredly one full of gratitude.

When I look back on the long stay I made at that time in Budapest, I say to myself, not without a trace of melancholy, that for a young man of a lively disposition there are more romantic adventures than to explain as a pedagogue one of La Fontaine’s fables, a tragedy of Racine’s, or “Le Neveu de Rameau.” Yet, if one considers, there is a certain touch of the comic novel in the idea of earning one’s livelihood by trying to persuade others that the things one loves oneself are lovable. When Don Quixote celebrated the merits of his Dulcinea, he could hardly have seemed, I imagine, more extravagant to Sancho than I must have appeared to my Hungarian students, when I unrolled before them my intellectual pack, and I have often told myself that they must secretly have thought that only my vanity as a Frenchman could have enabled me to discover in those admirable books the things which I pretended to find there. How often, while I talked to them, I thought, with a feeling of homesickness, of that cultivated Europe of the eighteenth century which had made French its natural language, and of those aristocrats who, in their lonely castles, took the same pleasure in reading our Encyclopedists, or our splendid classics, as we do ourselves! But then they had not waited till they had almost arrived at man’s estate to learn our language. From their childhood upward they had heard it round them, and no learned doctor from the Sorbonne could replace some old soldier, the flotsam of the Seven Years War, who after a thousand vicissitudes had said goodbye to his Burgundy or his Normandy and had one fine day come to rest in the capacity of tutor in some noble house of the Carpathians or the Puszta. But above all, in those blessed days, the sinister German culture had not yet arisen, to throw its false weights into the light scales of the spirit.

I was conscious that some of my young Hungarians were tempted to escape to Paris and initiate themselves into a life which they instinctively guessed was more free, more joyous, and more human than the German one. Only they were poor, and the scholarships which were granted to them for the completion of their studies stipulated invariably that they should go to Leipzig, Munich, or Berlin. The funds for these scholarships were furnished by Germany, which applied to the intellectual domain the same methods from which she drew such great advantages in her worldwide commerce. Thus she opened for the benefit of Hungarian intelligence a sort of account current, with the certainty of recovering, someday, a hundred percent interest on her money.

I should indeed have been fairly uncomfortable in that university, which was more than three quarters Germanized, if I had not found among those young Magyars a spontaneity and a youthful charm which caused them to evade with a smile or by sheer idleness the gloomy German discipline. Teutonic pedantry, which has today stultified all Central Europe, did not succeed in stifling the impulsive and idyllic character of the Hungarian spirit—all that rural poetry which finds its best expression in the poems of Petöfi, and especially in the work of John Arány, the disciple of Virgil and near relation of Mistral. The thing they love and understand with all their power and ingenuity is life on the great plains, where corn and vines and maize ripen and where immense herds of cattle, horses, and sheep are pastured. On this subject they possess a charmingly fantastic literature, at the same time realistic and spiritual, in which one sees the shepherd sharing fraternal sentiments with his beasts. It never rises above the modest limits of a tale, but within those bounds it is perfect. Ah! why do these Hungarians want to think in German fashion, when they would be so charming if they remained quite simply as nature has made them! How many of them, by doing so, have lost the qualities of a race which remained close to the soil, without acquiring in exchange the painstaking virtues of the Germans—if one can describe as virtues an infinity of faults and a sad deformation of human mentality!

Today, after nearly twenty years have elapsed, I return to Budapest. On the boat which carries me down the swift current of the broad Danube, with its banks fringed with willows, those distant impressions are mingled with another recollection which dates but from yesterday: the signature at Versailles of the treaty with Hungary.

It was in the Palace of Versailles, in a long and magnificent gallery decorated with mirrors and with panels representing the fountains, the grottoes and basins of Versailles. Through the open windows one saw, beneath a rather cloudy sky, the trees and lawns of the garden, while within a fairly numerous party of men and women were moving and chattering as if they were assembled for an elegant tea party. All of a sudden, an usher announced, in resounding tones, “The Hungarian Plenipotentiaries.” Then, in a silence charged with emotion, there advanced towards the horseshoe table, round which were seated about fifty diplomatists, a small group of men, their eyes fixed, their faces pale, and their carriage rather stiff. These were the men delegated by Hungary to sign, here in this hall scintillating with sunshine and full of the grace of summer, the act which took from their country two-thirds of the territory which had been hers for more than a thousand years. One stroke of the pen was about to detach from the Crown of Saint Stephen the vast range of mountains which encircles the great Hungarian plain, and the millions of inhabitants of diverse races, Slovaks, Ruthenians, Romanians, Serbs, Saxons, Tziganes, Jews, and pure Magyars—all that population which lives inextricably mixed in the Marches of Hungary. Under their faultless frock coats those plenipotentiaries seemed to me, at that moment, to resemble the burghers of Calais in their long, floating shirts, and I felt how heavily the keys which they carried must weigh in their hands. I knew the extent of their loss, and how strong was the sentiment which attached their Hungarian hearts to that millenarian domain. Charmingly romantic pictures rose in my memory: of high, silent valleys, the stampede of chamois through the snow; pine trees uprooted on the banks of torrents; ancient half-ruined castles crowning the summit of rock or forest, where heroes, whose legends were told to me, had lived; villages where poets, whose verses were recited to me, had been born; ancient patriarchal domains in which I had received hospitality. In spirit I heard something which resembled that farewell, so homely and tender, which the province of Szepes, detached from Hungarian territory by this Trianon Treaty, addressed to its old country, and of which, while writing these lines, I have the text before my eyes. “We have no intention,” say these people of Szepes, “to present an account, or to strike a balance. We only take our leave. We thank you quite simply for that good white flour with which we have been nourished for a thousand years, and which has made such delicious cakes for our children. We thank you for the wine of Tokai which has flowed nowhere so abundantly as with us. We thank you for the black cherries, the juicy apricots, the luscious grapes and the good red watermelons that the women of Eger sold in the markets of our towns. We thank you for the excellent Erdötélek tobacco, which you brought us at the same time as the lilies of the valley. And you, O ancient mountains, O shining peaks above the clouds, O lovely Alpine lakes with your emerald splendors, and thou too, O powerful Magura, that holdest the tomb of Arpad, the conquering prince of our fatherland, all of you, O distant blue mountains of Szepes, stand back! Let the song of the thrush be still! Let the murmur of the forest rustle alone, let it rustle through the mountainsand the valleys, let it carry our sighs to those to whom now we bid farewell!”

Meanwhile, one after another, the Plenipotentiaries had affixed their signatures at the foot of the sheet of paper. The Magyar delegates retired through the throng of spectators, who this time rose from their seats to make way for them. Outside a curt word of command was heard, followed at once by the rattle of arms: it was the guard saluting. Around us the hum of conversation had begun again. We crowded towards the buffet, and amid the sound of voices and of chairs being pushed back, I saw once more in spirit that whitewashed wall on which hung the portrait of that faraway author of this immense calamity: the man with broad-brimmed hat who had received me over there on that sad autumn evening, and whose eyes had watched over me day and night for four long years.

II▬ A Bulwark of the West ▬

This morning I climbed the hill of Buda, from which, in old days, I had so often contemplated the beautiful landscape that unfolds itself there: a vast semicircle of wooded hills, then the bare, muddy expanse of the Danube which flows at the foot of the rock, on the further side of the river, on its flat bank, the great new town of Pest, and beyond it the never-ending plain.

When I arrived there twenty years ago, the city of Buda, seated on its narrow plateau, was a small, ancient town, entirely provincial in character, consisting of low houses, at most one story high, and nearly all plastered over with a strange yellow limewash. One looked in vain for any of those palaces which the eighteenth century had so lavishly bestowed on Prague or Vienna, with their giant caryatides, their cornices decorated with a whole population of tormented statues, and their admirable balconies—all carried out in a fine Italian style of architecture, but in a somewhat more massive manner suitably adapted to a northern climate. At Buda, the palace of a magnate was a very simple dwelling, bourgeois in style and reminding one of the country. The only touch of art was given by the porch and the armorial bearings. The Hapsburgs never did anything to make the old hill splendid. Maria Theresa, who built so much in other places, erected nothing there but a long, monotonous building, which, moreover, has been pulled down in order that the new royal castle, pretentious and heavy like a modern palace hotel, should take its place. As for the Magyar nobles whom the court attracted to Vienna, they built themselves sumptuous residences there in the neighborhood of the Hofburg and contented themselves with a modest pied-à-terre at Buda, which they inhabited on the rare occasions when the king and queen came to Hungary.

Sometimes one sees, embedded in the yellow limewash which covers these low-built houses, a relief portraying the head of a decapitated Turk, or more often one reads an inscription: “Here in 1450 lived the Despot of Bosnia,” or “Here in 1388 stood the Palace of the Viceroy of the Banat,” or of such and such a Balkan prince. You enter under the archway, which is large enough to allow of the passage of a carriage and pair and you find yourself in a roughly paved yard, where grass is growing; there is a well in one corner and all round it are buildings, whose old roofs, with flat tiles, incline steeply towards the ground. All that remains of the Despot of the Banat, or the Hospodar of Walachia in that enclosure, is a fragment of a Romanesque arch, a cellar, a pillar round which a vine is trained and on which a canary’s cage is hung. Near these vestiges of a former age live small householders, retired public functionaries, or small artisans, leading their peaceful lives. But that Turk’s head, that pillar, or that arch are sufficient to awaken the imagination of the passerby and to remind him that on this hill, which today has become so squalid, great events took place in the past. That old rock of Buda, like Marathon, Salamis, or the Catalaunian Plains, is one of the historic places where the fate of our civilization hung in the balance in its struggle with the East. During many centuries, the vast plain, which ends at the foot of this high hill, exercised an irresistible attraction over the peoples of Asia. Along the road which they followed from the frontiers of China, it formed an admirable halting place where they could erect their tents for a while, let their horses breathe for a short space and, after watering them at the great river, once more resume their march towards the conquest and booty of the West. At the very foot of the hill of Buda, Attila established his camp, that celebrated Etzelburg, which, in the imagination of the poet of the Nibelungen, seemed to be the center of the world. After him many more hordes of Tartars or Mongolians disported themselves in that plain, appearing and disappearing like columns of dust, or like the mirages which the fairy Delibab delights to make appear on the horizon of those flat countries. Only the Hungarians, who came, it is said, from the region of the Pamirs, installed themselves firmly in the country. For a long time they were the terror of western Europe, until the day when, renouncing the worship of the White Stallion, they embraced the Roman religion and became the champions of Christianity against their brothers in Asia.

That happened a thousand years ago, in the reign of Saint Stephen the King. The hill of Buda was then still untenanted, for those war-like herdsmen cared only for vast pastures, where horses and sheep might graze peacefully, and which reminded them of the steppes from whence they came. But having been initiated by their new religion into the idea of life in cities, they climbed the hill and constructed on its summit, for the first time, churches, houses, and ramparts.

For centuries that fortified rock became the stake for which the East and West fought. From the far distant steppes, men with narrow eyes and yellow complexions came to attack it, and all feudal Europe rushed to its defense. Princes of the House of Anjou, grandnephews of Saint Louis, conducted a crusade here, at the same time bringing to Hungary the brilliant French civilization of the fourteenth century. From the Danube to the Adriatic, the country became covered with towns, castles, and monasteries. Here, on this very plateau, masons from Bray-sur-Somme erected a royal castle which was exactly like the admirable mansions of the Ile de France. Every day the sacred kingdom of St. Stephen became more and more like a Western country; when suddenly a new horde appeared, even more formidable than the Huns of Attila or the Tartars of Batu-Khan. During more than half a century, two Transylvanian heroes, John Hunyadi and Mathias Corvin, resisted the attacks of the Turks. The Angelus which is rung at midday still commemorates the service which they rendered to Christianity four hundred years ago. Never did the hill of Buda appear more brilliant than in those days, when its very existence was in peril every moment. Latin civilization, which had originally conquered the hill by bringing to it first Christianity and then the spirit of the Anjous, blossomed anew, but this time under the semi-pagan form of the Renaissance. King Mathias summoned Italian artists around him, built palaces and churches, and filled them with precious objects and unique manuscripts, so that his rude fortress became a town after the fashion of the cities of Tuscany and Umbria. Great wagons, accompanied by armed escorts, brought to Buda cloth from Flanders, wines from the Rhine, and all the other products of Europe. Then, continuing on their way through the Saxon villages of Transylvania, towards Adrianople and the East, they returned from thence laden with spices, perfumes, carpets, and damascened arms. The merchants also made use of the Danube route; innumerable galleys, navigated by Turkish slaves, ascended and descended the river in order to exchange their merchandise with Venetian vessels laden with the riches to be found in Italy and in the ports of the Levant.

Then suddenly the catastrophe came. The Hungarian Army was annihilated by the Janissaries at Mohacs, and the citizens of Buda carried the keys of their city to the conquerors at the ancient Alba Royal, the tomb of the earliest kings of Hungary. Asia installed itself on the hill. Everything that recalled France or Italy was destroyed or taken away. King Mathias’ cathedral became a mosque; Soliman’s galleys carried off, in twelve hundred buffalo hide cases, all the treasures of the town; and for a long time afterwards one could see the statues of Hunyadi, of Mathias Corvin and his wife, and the great bronze sconces which ornamented the palace, exposed as trophies on the Hippodrome at Byzantium. Towns, castles, monasteries were destroyed, and the whole country was ravaged. Hungary became once more what she had been at the time of the first invasions: an immense expanse of pasturage and swamps. Two and a half centuries later, when Charles of Lorraine, at the head of an army to which all the nations of Europe had contributed soldiers, once more attacked the fortress, nothing remained of the monuments and treasures which the Anjous and Hunyadis had gathered together there.