Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

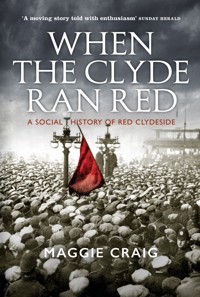

When the Clyde Ran Red paints a vivid picture of the heady days when revolution was in the air on Clydeside. Through the bitter strike at the huge Singer Sewing machine plant in Clydebank in 1911, Bloody Friday in Glasgow's George Square in 1919, the General Strike of 1926 and on through the Spanish Civil War to the Clydebank Blitz of 1941, the people fought for the right to work, the dignity of labour and a fairer society for everyone. They did so in a Glasgow where overcrowded tenements stood no distance from elegant tea rooms, art galleries, glittering picture palaces and dance halls. Red Clydeside was also home to Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the Glasgow Style and magnificent exhibitions showcasing the wonders of the age. Political idealism and artistic creativity were matched by industrial endeavor: the Clyde built many of the greatest ships that ever sailed, and Glasgow locomotives pulled trains on every continent on earth. In this book Maggie Craig puts the politics into the social context of the times and tells the story with verve, warmth and humour.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 473

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Maggie Craig is the acclaimed writer of the ground-breaking Damn’ Rebel Bitches: The Women of the ’45 and its companion volume Bare-Arsed Banditti: The Men of the ’45. She is also the author of six family saga novels set in her native Glasgow and Clydebank. She is a popular speaker in libraries and book festivals and has served two terms as a committee member of the Society of Authors in Scotland.

Also by Maggie Craig

Non-fiction

Damn’ Rebel Bitches: The Women of the ’45

Bare-Arsed Banditti: The Men of the ’45

Footsteps on the Stairs: Tales from Duff House

Henrietta Tayler: Scottish Jacobite Historian

and First World War Nurse

Historical novels

One Sweet Moment

Gathering Storm

Dance to the Storm

Glasgow and Clydebank novels

The River Flows On

When the Lights Come on Again

The Stationmaster’s Daughter

The Bird Flies High

A Star to Steer By

The Dancing Days

www.maggiecraig.co.uk

This edition first published in 2018 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

Copyright © Maggie Craig 2011, 2018

First published in 2011 by Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh

ISBN: 978 085790 996 1

The right of Maggie Craig to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh Printed and bound by MBM Print SCS Ltd, Glasgow

For my father,

Alexander Dewar Craig,

who first sang me the songs,

and first told me the tales of Red Clydeside;

and for the other exceptional human being who is his beautiful grandchild and our brilliant younger child.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Preface

1 Rebels, Reformers & Revolutionaries

2 The Tokio of Tea Rooms

3 Earth’s Nearest Suburb to Hell

4 Sewing Machines & Scientific Management

5 An Injury to One Is an Injury to All: The Singer Strike of 1911

6 No Vote, No Census

7 The Picturesque & Historic Past: The Scottish Exhibition of 1911

8 Radicals, Reformers & Martyrs: The Roots of Red Clydeside

9 Halloween at the High Court

10 Not in My Name

11 A Woman’s Place

12 Death of a Hero: The Funeral of Keir Hardie

13 Mrs Barbour’s Army: The Rent Strike of 1915

14 Christmas Day Uproar: Red Clydeside Takes on the Government

15 Dawn Raids, Midnight Arrests & a Zeppelin over Edinburgh: The Deportation of the Clyde Shop Stewards

16 Prison Cells & Luxury Hotels

17 John Maclean

18 Bloody Friday, 1919: The Battle of George Square

19 The Red Clydesiders Sweep into Westminster

20 The Zinoviev Letter

21 Nine Days’ Wonder: The General Strike of 1926

22 Ten Cents a Dance

23 Sex, Socialism & Glasgow’s First Birth Control Clinic

24 The Flag in the Wind

25 Socialism, Self-Improvement & Fun

26 The Hungry ’30s

27 Pride of the Clyde: The Launch of the Queen Mary

28 The Spanish Civil War

29 On the Eve of War: The Empire Exhibition of 1938

30 The Clydebank Blitz

Legacy

Select Bibliography

Index

List of Illustrations

Room de Luxe, the Willow Tea Rooms, Glasgow

Mother and child in Glasgow, 1912

‘A Cottage for £8 a Year’ (J. Robins Millar)

‘Left out!’ The Tragedy of the Worker’s Child’(J. Robins Millar)

Singer Sewing Machine factory, Clydebank, c.1908

Tom Johnston

Thomas Muir of Huntershill

Auld Scotch Street, Scottish Exhibition, 1911

Glasgow First World War female munitions worker

‘Hallowe’en at the High Court’ (Glasgow News, 1913)

Glasgow Rent Strike, 1915

Rent Strike poster

Willie Gallacher

John and Agnes Maclean and one of their daughters

Helen Crawfurd with children in Berlin, 1922

Mary Barbour in her bailie’s robes

Davie Kirkwood

The Queen Mary leaving the Clyde, 1936

James Maxton election postcard

Leaving Radnor Street, March 1941

Bloody Friday in George Square, 1919

Acknowledgements

I should like to express my sincere thanks to the following people and institutions for the help they gave me with my research and in supplying illustrations for this book: Audrey Canning, librarian, Gallacher Memorial Library, with special thanks for pointing me in the direction of Helen Crawfurd and Margaret Irwin; Carole McCallum, archivist, Glasgow Caledonian University; all those who contributed to Glasgow Caledonian University’s Red Clydeside website; the late Mr James Wotherspoon of Clydebank, still sharp as a tack at the age of 105; Pat Malcolm and her colleagues at Local Studies, Clydebank Library; Jo Sherington of West Dunbartonshire Libraries and Cultural Services; the librarians and all other staff at the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, with particular thanks to Nerys Tunnicliffe, Patricia Grant, and Martin O’Neill; Claire McKendrick, Special Collections, University of Glasgow Library; The Willow Tea Rooms, Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow; James Higgins and Christine Miller of Bishopbriggs Library; David Smith of East Dunbartonshire Leisure and Culture Trust; Marie Henderson of Glasgow Digital Library at the University of Strathclyde; Shona Gonnella and Anne Wade at the Scottish Screen Archive, National Library of Scotland; Kevin Turner of the Herald and Evening Times photo library; Neil Fraser of SCRAN; the Marx Memorial Library for permission to quote from Helen Crawfurd’s unpublished memoirs; and, for permission to quote from his poem on the launch of the Queen Mary, The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of John Masefield.

I should also like to express my appreciation of all the Bankies over the years who have shared with me their memories of the Clydebank Blitz, some of whom have now passed on. They have included Margaret Hamilton, Grace Peace, Grace Howie, Joen McFarlane, Jean Morrison, Andrew Hamilton and the late Maisie Nicoll, née Swan, with special thanks to Maisie for the pianos. My late parents, Alexander Dewar Craig and Molly Craig (née Walker), also told me of their experiences in Clydebank and Glasgow on those two terrifying nights in March 1941. For the first, hardback, edition of this book, thanks are due also to Kate McLelland for another great cover, and to everyone at Mainstream, most particularly Ailsa Bathgate and Eliza Wright.

For this new paperback edition, I’d like to thank Helen Bleck for her meticulous and sensitive copyediting. My thanks also go to Andrew Simmons, Tom Johnstone and all at Birlinn, and to James Hutcheson for the cover design.

I’d also like to thank the wonderful Will, Pim, Alexander and Ria for all their love and support, with special thanks to Ria for coming up with le mot juste in the nick of time.

Preface

This book is about Red Clydeside, those heady decades at the beginning of the twentieth century when passionate people and passionate politics swept like a whirlwind through Glasgow, Clydebank and the west of Scotland. It’s also about the world in which those people lived. My aim has been to paint a vivid picture, telling the story by placing the people and their politics within the wider context of the place and the times.

These were years of great wealth and appalling poverty, when Glasgow was home to some of the most magnificent public buildings in Europe and some of its worst slums. This Glasgow welcomed the world to spectacular open-air exhibitions, chatted with its friends in elegant art nouveau tea rooms, fell in love with the movies in glittering art deco picture palaces and tangoed and foxtrotted the night away in the palais-de-danse which dotted the city.

This Glasgow also lost a thousand young adults each year to tuberculosis (TB). Overcrowded and insanitary tenements where a bed to yourself was an unheard-of luxury provided the perfect breeding ground for this terrible illness. Other spectres stalked the poor. Thousands of Glasgow’s children were born to die. Thousands of women had a child every year until it killed them, dying worn-out before they were even 40 years old.

Outside the home, men and women worked exhaustingly long hours for low pay in filthy conditions where health and safety had never even been thought of. Horrific workplace accidents were commonplace. Find yourself incapacitated by such an injury and the most you could hope for to help pay the rent and feed your family was a whip-round organised by your workmates.

National insurance was introduced only in 1911 and did not extend to workers’ families or the unemployed. There was no social security or National Health Service. Other than the absolute last resort and shame of going on the parish, only the kindness of others caught you when you fell. Small wonder that one Red Clydesider described this Glasgow as ‘Earth’s nearest suburb to hell’.

Yet poverty, an unequal struggle and lack of opportunity do not always breed despair. Sometimes they breed a special kind of man or woman, one who uses their anger and apparent powerlessness to fuel a fight for justice and fair treatment for everyone. The Red Clydesiders belonged to this special breed. So did my father.

Growing up in Old Monkland in Coatbridge during the Depression of the 1930s, he and his family knew real hardship. Yet they knew how to laugh too, as they knew how to tell stories. A railwayman who worked his way up from shunter to stationmaster, my father travelled all over Scotland in his work and he knew the story behind every stone. A Buchan quine who loved her adopted Glasgow, my mother too had her stories to tell, as did our battalion of aunts and uncles. Two in particular whose experiences are included in this book are Alex McCulloch and his wife Elizabeth (née Craig), our family’s beloved Aunt Elizabeth and Uncle Alex.

Growing up where I did, my earliest memories are of Clydebank and the Clyde and all the stories that went with them. Active in Labour politics and a life-long member of the National Union of Railwaymen, many of my father’s stories were about the Red Clydesiders.

Rebels, reformers and revolutionaries, these radicals, socialists and communists were larger-than-life characters, yet approachable to all. Far beyond their own family and social circles they were known by the affectionate diminutives of their first names. It was always Jimmy Maxton, Davie Kirkwood, Wee Willie Gallacher, Tom Johnston, Manny Shinwell.

It was during the turbulent years before, during and after the First World War that the Clyde earned the sobriquet of Red Clydeside. I’ve extended that period to include the General Strike of 1926, the Hungry Thirties, the Spanish Civil War of the late 1930s and the Clydebank Blitz of 1941. The great Clydebuilt ships belong in there too.

Meeting a debt of honour to my family and forbears, I wrote six novels set in Glasgow and Clydebank during the years when the Clyde ran red. This is the history that goes with them.

Enter, stage left, the Red Clydesiders.

1

Rebels, Reformers & Revolutionaries

‘Distorted and destroyed by poverty.’

James Maxton was one of the great personalities of Red Clydeside. Known as Jimmy (or Jim) by friends and family, he was a man of great warmth, compassion and charisma. An inspiring public speaker, he could hold huge audiences in the palm of his hand, moving them to tears one moment and making them laugh out loud the next. His sense of humour was legendary, sometimes sardonic and cynical, but never cruel. Born in 1885, Maxton served for more than 20 years as a Labour MP at Westminster, where he also shone as an orator. Loved by his friends and respected by his political foes, he was described by Sir Winston Churchill as the greatest gentleman in the House of Commons. Former UK prime minister Gordon Brown wrote an engaging biography of him, entitled simply Maxton.

Maxton was born into a family which, while not wealthy, was quite comfortably off. Both his parents were teachers. His mother had to give up her career when she married, as female teachers of that time were obliged to do. Young Jimmy grew up as one of five children in a pleasant villa on a sunny ridge overlooking Barrhead near Paisley at the back of the Gleniffer Braes. He is remembered there today in the names of surrounding streets and the Maxton Memorial Garden.

Tragedy struck the Maxtons when Jimmy was 17 years old. After a swim during a family holiday at Millport on the Isle of Cumbrae in the Firth of Clyde, his father had a heart attack and died. Left in strained circumstances though she was, Melvina Maxton was determined her two sons and three daughters were going to be educated as far as their brains would take them. Her determination paid off. All five became teachers.

His tongue firmly in his cheek, James Maxton was later to observe that his mother should really have sent him and his older siblings out to work. With typically cheerful sarcasm, he recalled that the family lived during those years after his father’s death in ‘the poverty that is sometimes called genteel’. It was a real struggle, although it helped that Maxton had won a scholarship at the age of 12 to the highly regarded Hutchesons’ Grammar School, known more informally as ‘Hutchie’. He did well, though he wore his learning and intelligence lightly, awarding himself some tongue-in-cheek distinctions. Honours in tomfoolery, first class honours for cheek, failure in intellectuality and honours advanced in winching. Unlike wench, this word could apply to both sexes, allowing grinning west of Scotland uncles to thoroughly embarrass both teenage nieces and nephews by asking, ‘Are ye winchin’ yet?’

Although nobody would have called James Maxton handsome, his dark and saturnine looks were undeniably striking. His tall frame and long, lantern-jawed face were framed by straight black hair which he wore much longer than was then fashionable or even acceptable. Curling onto his collar, it gave him a rather theatrical air. You could easily have taken him for an actor.

When he first went to Glasgow University his long hair was as far as any youthful rebellion went. He met Tom Johnston there. Later a highly respected Secretary of State for Scotland and prime mover behind the creation of the hydro-electric dams and power stations of the Highlands, Johnston was a young political firebrand from Kirkintilloch who took great delight in scaring the lieges through the pages of the Forward, the weekly socialist newspaper he founded in 1906. When he first got to know James Maxton, Tom Johnston described him as a ‘harum scarum’ who just wanted to get his MA so he could make his living as a teacher. Maxton himself said the only activities in which he excelled at university were swimming, fencing and PE. He was a good runner too.

As his contemporary at Glasgow University, Johnston’s first memory of him was indeed a theatrical one. A group of students had gone together to the Pavilion Theatre, where the evening grew lively with ‘the throwing of light missiles to and fro among the unruly audience’. Young gentlemen and scholars indulging in some youthful high jinks. Throwing the well-educated hooligans out failed to dampen their enthusiasm. Maxton and his co-conspirators managed to get back in through the stage door and onto the stage, where they ‘appeared from one of the wings, dancing with arms akimbo to the footlights’.

It wasn’t long before the light-hearted young Mr Maxton began to think seriously about politics. Tom Johnston was an influence. So was John Maclean, the tragic icon of Scottish socialism. When Maxton was at Glasgow University in the early 1900s Maclean was four years older than him and had already got his MA degree. They often met by chance on the train, travelling into Glasgow from Pollokshaws, where they both then lived. A teacher by vocation as well as training, Maclean used these railway journeys to tell Maxton about Karl Marx.

Glasgow taught Maxton about life, especially when he began working as a teacher and saw the effects of poverty on his young pupils and their families. Later in life, in a 1935 BBC radio broadcast called Our Children’s Scotland, he spoke about how his experiences had influenced his thinking: ‘As a very young teacher, I discovered how individualism and their individualities were cramped, distorted and destroyed by poverty conditions before the child was able to react to its environment. That was the deciding factor in bringing me into the socialist and Labour movement.’

Maxton was 19 when he made the decision in 1904 to join the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Founded by Keir Hardie, Robert Cunninghame Graham and others who saw that the Liberal Party was not going to solve the problems of the poor, the ILP was particularly strong in Glasgow and the west of Scotland, one of the engines which powered Red Clydeside. Although later a component part of what is now the modern Labour Party, it was always a more radical group. As one of the ILP’s most influential members, James Maxton devoted the rest of his life to politics, one of the band of Labour MPs which swept to power in the pivotal general election of 1922. Tom Johnston was also in that group.

Only once did a heckler get the better of James Maxton, as Tom Johnston recalled. Not long after he graduated from Glasgow University, Maxton returned to address a meeting at the Students’ Union.

That meeting remains in my memory for an interruption which, for once, left Maxton speechless and retortless. Maxton by that time had grown his long tradition-like actors’ hair, and during his speeches he would continually and with dramatic effect weave a lock away from his brow. At this Students’ Union gathering he was set agoing at his most impressive oratory … ‘Three millions unemployed (pause). Three millions unemployed (pause). Three millions unemployed (pause).’ Amid the tense silence came a voice from the back: ‘Aye, Jimmy, and every second yin a barber!’

James Maxton’s friend John Maclean comes across as a more sombre character. He was only eight when his father died, the catastrophe plunging his mother and her four surviving children into a poverty which was not at all genteel. Like Melvina Maxton, however, Anne Maclean was a woman determined that her children should be educated.

Both John Maclean and James Maxton lost their jobs as schoolteachers because of their political activities, which particularly aggravated their employers when they spoke out against the First World War and conscription. Maclean remained a teacher but outside the system, devoting himself to public speaking, writing articles, running the Scottish Labour College which he founded, and imparting the theory of Marxist economics in night and weekend classes. He advocated revolution rather than reform, his self-appointed mission being to convince the working classes the only solution to their ills was socialism, and that the only way to get that would be by seizing power. The ruling classes were never going to give it away.

Tom Johnston was a rebel rather than a revolutionary. Passionate, romantic and idealistic, he too could be cheerfully sarcastic, as when he described the decisions taken at the start-up of the Forward. ‘We would have no alcoholic advertisements: no gambling news, and my own stipulation after a month’s experience, no amateur poetry; every second reader at that time appearing to be bursting into vers libre.’

Johnston’s sarcasm grew savage when he researched and wrote The History of the Working Classes of Scotland and Our Scots Noble Families. Often more simply referred to as Our Noble Families, this was published in 1909, when Johnston was 28 years old. One of his targets was the Sutherland family, notorious for the role they played in the Highland Clearances. He fired his first shot at one of their forebears.

I began to be interested in this Hugo. He floats about in the dawn of the land history of Scotland, murdering, massacring, laying waste and settling the conquered lands on his offspring.

Rooted in theft (for as every legal authority admits, the clan, or children of the soil, were the only proprietors), casting every canon of morality to the winds, this family has waxed fat on misery, and, finally, less than 100 years ago, perpetrated such abominable cruelties on the tenantry as aroused the disgust and anger of the whole civilised world.

The Forward soon attracted an impressive array of writers. H.G. Wells allowed the paper to carry one of his novels as a serial. Ramsay MacDonald wrote for it, as did suffragette leader Mrs Pankhurst. James Connolly was also a contributor. Born in Edinburgh of Irish parents, Connolly was a revolutionary socialist and Irish nationalist, shot by firing squad after the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin. The socialist newspaper also benefited from the skill of artist J. Robins Millar, who drew many cartoons for it. A man of many talents, Millar went on to become a playwright and the doyen of Glasgow’s theatre critics.

Trying to cover all bases, the young editor was sincere in his views but very astute. Committed socialist and devout Catholic John Wheatley attracted readers with the same deep religious faith as himself, helping many of them realise it was possible to be both a Catholic and a socialist. That had taken some doing. When Wheatley first declared himself to be a socialist his local priest and some members of the congregation were so horrified they made an effigy of him and burned it at his front gate. Wheatley opened the door of his house, stood there with his wife and smiled at them. The next Sunday morning he went to mass as he usually did and the fuss soon died down.

The eldest of ten children, John Wheatley was born in County Waterford in Ireland in 1869. Taking the path of many with Irish roots who feature in the story of Red Clydeside, his family came to Scotland when John was eight or nine years old. The Wheatleys settled in Bargeddie, then known as Braehead, at Coatbridge. At 14 John followed in his father’s footsteps and started working as a coal miner in a pit in Baillieston.

Wheatley was a miner for well over 20 years, during which time he educated himself and became involved in politics, another path many Red Clydesiders followed. In his late 30s Wheatley set up a printing firm and joined the ILP. Two years later he was elected a county councillor. He was in his early 50s when he too became one of the 1922 intake of Labour MPs, sitting for Shettleston.

Wheatley was much respected by his younger colleagues, especially James Maxton, who admired his intellect and organising ability. Ramsay MacDonald, Britain’s first Labour prime minister, saw Wheatley’s abilities too, appointing him Minister for Health in the first Labour government of 1924.

Another writer in the Forward stable was a coal miner from Baillieston who, under a pseudonym, specialised in laying into the coal owners and the vast profits they made at the expense of the miners who worked for them. Patrick Joseph Dollan later became Lord Provost of Glasgow.

The Red Clydesiders were always passionate about children, education, health and housing. Look at the Glasgow of the early 1900s and it is not hard to see why.

Yet this was a city which presented many different faces to the world.

2

The Tokio of Tea Rooms

‘Very Kate Cranstonish.’

In the early years of the twentieth century Glasgow was the Second City of the Empire and the Workshop of the World. Scotland’s largest city and its surrounding towns of Clydebank, Motherwell, Paisley and Greenock blazed with foundries and factories, locomotive works, shipyards, steel mills, textile mills, rope works and sugar refineries. This was the time when the North British Locomotive Works at Springburn produced railway engines which were exported to every continent on earth and shipbuilding on the Clyde was at its peak. The proud boast was that over half the world’s merchant fleet was Clydebuilt.

In 1907 John Brown’s at Clydebank launched the Lusitania, a Cunard liner destined for the North Atlantic run. The Aquitania was to follow in 1914. Before the Second World War came two of the most famous ocean liners of all, the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth. The names of these Cunarders are redolent with the elegance of a bygone age.

Glasgow was elegant too. Talented architects such as Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson and John Thomas Rochead, who also designed the Wallace Monument at Stirling, had fashioned a cityscape of infinite variety. The Mossmans, a family of sculptors, had adorned a huge number of Glasgow’s buildings with beautiful life-size stone figures often inspired by the mythology of Ancient Greece and Rome. These included the caryatids which decorate what is now the entrance to the Mitchell Theatre and Library in Granville Street, formerly the entrance to St Andrew’s Halls. When they burned down in 1962, only the façade was saved. So many of the dramas of Red Clydeside were played out here, in what is now the Mitchell Library’s café and computer hall.

In 1909 Charles Rennie Mackintosh finished the second phase of the project which gave the city and the world the Glasgow School of Art in Renfrew Street. Five years before that, he and his wife and artistic partner Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh created the Willow Tea Rooms in Sauchiehall Street for Mackintosh’s patron, highly successful Glasgow businesswoman Miss Kate Cranston.

Along in the West End stood the extravagant red sandstone of the new Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery. Completed in 1901, it has been known and loved by generations of Glaswegians ever since simply as the Art Galleries, even if the young man about town who wrote it up in a guidebook called Glasgow in 1901 had fun describing it as ‘architecture looking worried in a hundred different ways’. In 1911 the builders were once again busy at Kelvingrove. Glasgow was looking forward to the third great exhibition to be held there. The Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry was scheduled to open at the beginning of May.

The gorgeously Italianate City Chambers dominated George Square, a physical manifestation of Glasgow’s good conceit of itself. John Mossman created some of the figures which decorate it in his studio on the corner of North Frederick Street and Cathedral Street. On the other side of the square rose the dignified and rather more subtly ornamented Merchants’ House. Designed by John Burnet senior, it had additions by his son and namesake. John Burnet junior crowned the highest point of the building with a model of the globe on top of which a sailing ship still rides the waves.

The Bonny Nancy belonged to Mr Glassford, one of Glasgow’s powerful eighteenth-century Tobacco Lords. She’s a reminder that the city’s fortunes were founded on trade and the enterprise of her traders. Those convivial gentlemen used to raise their glasses of Glasgow Punch – take about a dozen lemons, add sugar, Jamaica rum, ice-cold spring water and the juice of a few cut limes – in a confident and cheerful toast: ‘The trade of Glasgow and the outward bound!’

Work had to be done on Glasgow’s route to the sea before that trade could develop. People had first settled by the Clyde because the shallow river gave them fresh water and abundant fish, and was easy to ford. As ships grew larger the lack of depth became a problem. Goods had to be brought overland from Port Glasgow, causing delays and extra expense. Early civil engineering works such as the Lang Dyke off Langbank forced the Clyde into a narrower channel. Routine dredging also began, rendering the river navigable all the way up from Port Glasgow and the Tail of the Bank to the heart of Glasgow.

The ‘cleanest and beautifullest and best built city in Britain, London excepted’, which Daniel Defoe had so admired in the eighteenth century, could now grow into one of the world’s busiest ports. The deepened river also made shipbuilding possible. The Clyde made Glasgow, and Glasgow made the Clyde.

The Anchor Line was one of many shipping companies operating out of Glasgow in the early 1900s. Its impressive headquarters in St Vincent Place, just west of George Square, was faced with white tiles from which the grime of an industrial city could more easily be cleaned off. And Glasgow was dirty. Soot-blackened. Buildings of honey-coloured sandstone took only a few years to become as black as the Earl of Hell’s waistcoat. Anyone who lived in Glasgow or Clydebank before the Clean Air Act of the early 1960s will remember the choking yellow fogs of winter. They owed as much to what was streaming out of factory chimneys as they did to the damp climate of the west of Scotland.

There were few controls on pollution in the early 1900s. Factories, foundries and shipyards were risky places. The people who worked in them took their chances, no other choice being available to them. In this city of nearly a million and a half souls, life for the majority was about economic survival. Over the course of the nineteenth century, people in search of work, and – just maybe, if the fates allowed – a better life for themselves and their families, flooded into Glasgow. Most came from the Highlands and from Ireland, some from farther afield. Traditionally a first settling point for new immigrants, the Gorbals became a predominantly Jewish area, many of those Jews fleeing persecution in Poland and Russia.

Meanwhile, as electric trams took over from horse-drawn ones and local rail links improved, comfortably off Glaswegians decamped to developing suburbs like Bearsden and Pollokshields. What they sought and found there were lawned gardens, woods, open spaces and plenty of fresh air. In suburbs north and south of the Clyde laid out with wide avenues and parks filled with trees, boating ponds, tennis courts and putting greens, families enjoyed life. The lucky few lived in spacious, high-ceilinged villas designed by some of those great Glasgow architects, others in solid tenement flats of warm red and honey sandstone. Out in the suburbs the stone had more chance of retaining its light colour.

Tradesmen who had worked their way up also moved out, taking their families to new houses built on old farmland which aimed to achieve a village-by-the-city feel. The dream of living in a country cottage where your children could play in a flower-filled garden with vegetables growing outside the kitchen door is an old and powerful one. It was shared by the socialists of Red Clydeside.

John Wheatley came up with the idea of the £8 cottage, so-called because that was what the yearly rent would be. A cartoon by J. Robins Millar in the Forward in 1911 shows a father coming home from his work to be greeted by his young son and daughter running eagerly towards him. His wife stands behind the low fence which surrounds the neat, well-tended garden behind them, the baby in her arms. The first development in this style in Scotland was started before the First World War and finished after it by a housing co-operative of working-class families chaired by Sir John Stirling-Maxwell of Pollok. Lying between the modern-day Switchback and the Forth and Clyde Canal, the original name makes the aspiration clear: Westerton Garden Suburb. It’s now simply Westerton but its residents continue to refer to it as ‘the Village’.

Westerton had a railway station, a school, a village hall, a post office and shops. With its grocery and drapery, Westerton Garden Suburb Co-operative Society was an offshoot of the larger Clydebank Co-op. If you wanted the bright lights of the city, they were on your doorstep, a short journey away by train, tram or bus. Step off onto Sauchiehall Street or Buchanan Street and you would find wonderfully opulent shops like Treron’s, Daly’s, Copland & Lye’s, Wylie & Lochhead’s, Pettigrew & Stephen’s, the jewellers of the Argyll Arcade, each offering all manner of delights: glittering gems, bracelets and necklaces, perfume, lace wraps and handkerchiefs, kid gloves, fox furs and the latest fashions from Paris.

The wives and daughters of Glasgow’s industrialists, shipowners and businessmen could wander freely through this enchanted forest of gleaming wood and shining glass counters. Department stores were a transatlantic import which proved wildly popular in Glasgow. After the shopping was done it would be up in the ornate brass lift to the restaurant to sip coffee while a pianist played discreetly in the background. Or you could go to one of the city’s fashionable tea rooms. Glasgow made two indispensable contributions to the popularity of the cup that cheers. Sir Thomas Lipton, the man whose name is still synonymous with tea around the world, was born in the Gorbals; and it invented the tea room.

It was not the famous Miss Cranston who originally came up with the idea but her brother, Stuart. A tea merchant who was an evangelist for the quality of what he sold, he offered his customers a tasting before they made a purchase. In 1875 he moved to new premises on the corner of Argyle Street and Queen Street, put out a few tables and chairs, offered some fancy baking to go with the tea, and started a trend.

Tea rooms were tailor-made for Glasgow’s ladies of leisure. Their husbands and sons could go into pubs and chop-houses. In 1875 the department store hadn’t quite arrived and there were few places where respectable women could go alone and unchaperoned. Tea rooms allowed them to meet up with their friends for a chat in safe and pleasant surroundings.

Kate Cranston raised the tea room to an art form. She owned and managed four in Glasgow, in Ingram Street, Argyle Street, Buchanan Street and, most famous of all, the Willow Tea Rooms in Sauchiehall Street. In her patronage of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, his artist wife Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh and their equally talented friends, Miss Cranston gave what became known as the Glasgow Style a stage on which it could flourish and grow. She was very much identified with this achingly fashionable and very modern look. Soon everything influenced by it, be that furniture, home décor or the crockery with which you set your table, was described not only as ‘artistic’ but also as ‘very Kate Cranstonish’.

Oddly enough, although she was happy to give young designers such as Mackintosh and George Walton carte blanche to be as modern as they liked, she never updated her own personal style. Born in 1849, until she died in 1933 she always wore the long, full skirts and extravagant flounces of the Victorian era. Her only bizarre variation was to sport a cloak and sombrero.

Once the Cranstons had thought up the idea, tea rooms sprouted all over Glasgow and beyond. By 1921 the well-known City Bakeries had dozens of branches and ran a profit-sharing scheme with its bakers and waitresses. The 1930s saw the establishment of Wendy’s tea rooms. They offered the homely atmosphere of the country in the bustle and smoke of the big city: back to the rural idyll.

Reid’s in Gordon Street gave men the chance to meet their friends over coffee and a smoke, in separate smoking rooms, of course. Miss Cranston provided those to her gentlemen customers at the Willow Tea Rooms in Sauchiehall Street, along with billiard rooms. Those were on the second floor, the Room de Luxe with the high-backed silver-painted chairs designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh on the first.

In 1915 John Anderson’s Royal Polytechnic in Argyle Street, advertising itself as it was always known to Glaswegians as the ‘Poly’, offered ‘A Restful Den for Business Men’ in its Byzantine Hall. The delights of ‘Glasgow’s Grandest Smoke Room’ encompassed ‘fragrant coffees, delicious teas, telephones, magazines and all the leading newspapers’.

In 1916 Stuart Cranston opened a new tea room in Renfield Street which included a cinema. This tea room became a popular gathering place for members of the ILP. During the First World War, Renfield Street itself became a focus for regular Sunday afternoon open-air meetings opposing the war.

Tea rooms appealed to men as well as women, particularly those who supported the temperance movement. The majority of the socialists of Red Clydeside did, having too often seen the damage alcohol could do. Willie Gallacher, a key figure in the story of Red Clydeside, grew up in poverty in Paisley in the 1880s and ’90s, the son of an Irish father and a Highland mother. He was only 14 when he joined the temperance movement, having very personal reasons to hate alcohol. Gallacher’s father was a good husband and an affectionate parent but his dependence on drink blighted family life. As Gallacher later wrote: ‘I was still very young when my father died, but my eldest brother was already a young man. He was my mother’s favourite child. She was fond of all of us, but how she adored the oldest boy! When he developed a weakness for alcohol it almost drove her crazy. Her suffering was so acute that I used to clench my boyish fists in rage every time I passed by a pub.’

Many men, particularly young ones living what could be a lonely life between work in a Glasgow office and lodgings, went to tea rooms to enjoy the company of the waitresses. The book which poked fun at the architecture of the Art Galleries waxed lyrical on the subject. Glasgow in 1901 was written by three young men as a kind of guidebook, advising visitors who would be in the city for the exhibition of that year on local ways of going about things.

Describing Glasgow as ‘a very Tokio for tea rooms’, Archibald Charteris found it a great delight that tea-room waitresses were Glasgow girls who spoke with a warm Glasgow accent, ‘the most accessible well of local English’. Describing what could happen after a young woman started working at a particular tea room, he was at pains to point out that she and her colleagues were highly respectable young ladies.

Once installed, she may discover that a covey of young gentlemen wait daily for her ministrations, and will even have the loyalty to follow her should she change her employer. This is the only point in which she resembles a barmaid, from whom in all others she must be carefully distinguished.

To other people she has a more human interest, and to a young man coming without friends and introductions from the country, she may be a little tender. For it is not impossible that, his landlady apart, she is the only petticoated being with whom he can converse without shame. So the smile which greets him (even if it is readily given to any other) is sweet to the lonely soul, and a friendly word from her seems a message from the blessed damosel.

Kate Cranston did not escape the censure of the Red Clydesiders. An article published in the Forward on Saturday, 15 July 1911, was headed ‘How Miss Cranston Treats Her Workers’, with a subtitle of ‘The Limit of Tea Room Generosity’. The piece was based on a set of typewritten ‘Rules for Girls’, so presumably one of those girls had made a copy of those rules and smuggled it out. Did Miss Cranston investigate afterwards to try to establish who the culprit was?

Hours were long. Six days a week, Miss Cranston’s waitresses worked from seven in the morning till eight at night, five o’clock on Saturdays, except at the Willow Tea Room in Sauchiehall Street, which stayed open until eight o’clock on Saturdays too. Hours for girls under 18 were ‘not to exceed 74 per week’. Unless you worked at the Willow, you were working 74 hours a week anyway. Maybe the breaks weren’t counted, although these were not very generous. The Forward drew particular attention to the lunch break of only ten minutes, where each girl was provided with a cup of cocoa or a glass of hot milk and a biscuit.

In 1920 discontent among the waitresses who worked in Kerr’s Cafés boiled over into a strike. Their boss was William Kerr, who advertised himself as ‘the military caterer’. If his management style followed military lines, that may well have been part of the problem. A leaflet was printed to alert the people of Glasgow to the conditions under which the waitresses in Kerr’s Cafés worked:

Sweated Workers in Glasgow

STRIKE OF WAITRESSES AT KERR’S CAFES

Citizens of Glasgow, your attention

is drawn to the conditions which prevail

at above establishments:

12/– per week for 12 hours per day

1/– deducted if girl breaks a plate

9d deducted if girl breaks a cup

6d deducted if girl breaks a saucer

2/– deducted if girl breaks a wineglass

3d deducted for being late in morning

The Girls decided to join the Union, with the result that the Shop Steward was dismissed, which is quite evidently an attempt to undermine the Girls’ Union.

Previous to joining the Union, the minimum wage of restaurant workers was 10/– per week, and they had to purchase uniform from the firm.

We are asking the public to

SUPPORT THE GIRLS

Some of Kerr’s Cafés stayed open for late suppers till quarter to eleven at night, so presumably being late for work the following morning was a not uncommon occurrence. The strike lasted less than a month and during it most of the waitresses at Kerr’s voted with their feet and went looking for work elsewhere.

Harry McShane, Red Clydesider and Marxist, described the wages earned by the waitresses at Kerr’s as pitiful. Yet away from the clinking of china cups, cake stands piled high with scones, shortbread and chocolate eclairs and the stylish décor of Miss Cranston’s artistic tea rooms, there were plenty of Glaswegians who would have leapt at the chance to earn even those pitiful few shillings.

3

Earth’s Nearest Suburb to Hell

‘A whole world of sacrifice and effort.’

Helen Jack, who became better known under her married name of Helen Crawfurd, was born in 1877 in Glasgow’s Gorbals, where her father was a master baker. In her unpublished memoirs of her life and times she neatly summed up the character of her birthplace as a Jewish working-class district.

Her father William had an open-minded attitude towards his many Jewish neighbours not always usual among Gentiles at this time, now and again attending services at his local synagogue. He also had a highly developed social conscience in respect of the poorer families among whom he and his more well-off family lived. He and his wife brought their children up to have a strong religious faith and this Christian family practised what it preached.

When times were especially hard in the Gorbals during a strike, William Jack set up a soup kitchen in his bakery for those struggling to feed themselves and their families. As Helen later remembered, even as a master and a man who voted Conservative his sympathies were always with the workers. As committed as he was to helping their fellow men and women, Helen’s mother and grandmother ran the soup kitchen. See the problem, work out what you can do about it and then do it. The example set was to form the pattern for Helen Crawfurd’s life.

Mrs Jack, also Helen, helped foster that social conscience in her children by what she read to them. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a favourite. Her daughter remembered that she and her brothers and sisters would call to their mother not to start reading until they had fetched their hankies, because they knew they would not be able to hold back the tears when they heard ‘this tragic story of negro suffering’.

Helen junior saw suffering in Glasgow too, and with fresh eyes when the Jack family returned to the city after some years living in gentler surroundings near Ipswich in England. By now 16 years old, the maturing young woman was horrified by the Glasgow of the 1890s.

I was appalled by the dirt, poverty and ugliness I saw all around in Glasgow. I felt that other women along with myself must feel the same resentment and indignation. I watched the faces of the workers in tramcars and buses. They were worn with worry. I do not think any city had more people with bad teeth. In my young days orthopaedic surgery was in its infancy, and a great many people in Glasgow had bandy or bow legs and were undersized. The women carried their children in shawls, and the soft bones became bent. It has been stated that Glasgow’s water supply then lacked certain lime essential for bone building. To-day it is unusual to see these deformed people, but in my youth they were very common. The housing conditions and the death rate of infants were appalling.

One statistic in particular struck her. Occupied by large families though they were, 40,000 of Glasgow’s tenement flats consisted of only one room and a kitchen. She wrote with feeling of how, when a member of the family died, the living had to share that one room with the body of their loved one till the day of the funeral. That loved one would too often have been a baby. Infant mortality in late nineteenth-century Glasgow was indeed appalling and this grim statistic was to grow even worse. In the years immediately following the First World War, 40 per cent more babies died in infancy in Glasgow than in the rest of Britain as a whole. One in every seven children in the city did not reach their first birthdays.

The differences within Glasgow were also appalling, as statistics from 1911 show. That 29 babies in every 1,000 in middle-class Kelvinside died in infancy might shock and sadden us but down in the working-class Broomielaw the figure was even worse, standing at a horrific 234. In the Gorbals there were 145 infant deaths per 1,000 births, in Springburn 117. The most recent figures, for the whole of Glasgow in 2015, are of four infant deaths per 1,000 births.

The Red Clydesider who described Glasgow as ‘Earth’s nearest suburb to hell’ was James Stewart, better known as Jimmy. Another of those Labour MPs who was to triumphantly enter Parliament in 1922, he knew what he was talking about. A hairdresser to trade, he kept the patients at Glasgow Royal Infirmary neat and tidy. Diphtheria, scarlet fever, pneumonia, all these diseases were rife. The great scourge, the captain of all the men of death, was tuberculosis, also known as consumption or phthisis. TB claimed 1,000 lives in Glasgow each year and its favoured victims were young adults. Spreading as it did where people lived on top of one another in overcrowded and unhygienic tenements, it was considered a disease of the poor and the feckless. There was shame attached to contracting TB.

The tenement is a distinctive form of architecture. It provided many Glaswegians with elegant, spacious and comfortable homes, others with less grand but no less substantial and respectable ones: and then there were the slums. As bare of comfort inside as they were rundown outside, many of these grimy grey tenements pressed hard against the city centre, well within walking distance of Glasgow’s great public buildings and elegant shopping streets.

That so many well-off Glaswegians made their homes to the west of the city was no accident. That move had begun in Victorian times when the university, always known as the Old College, left its medieval home in the High Street in 1870. This was taking the students away from the beating heart of the old city but also from dingy closes packed tightly with slums which were breeding grounds for crime, violence and disease.

The Victorian city fathers commissioned photographer Thomas Annan to record the slums of Old Glasgow for posterity, the wynds and vennels crammed in behind the High Street and around the Briggait, south of Glasgow Cross. Staring back at the photographer, barefoot children and women in shawls stand under washing dangling from high poles sticking out across the narrow closes and alleyways of these shadowy spaces.

Up on Gilmorehill in the West End the students were able to breathe clean air. Like the well-off Glaswegians who were lucky enough to live in the gracious Edwardian townhouses of Park Circus, they could trust the prevailing westerly winds of the British Isles to blow any pollution or nasty smells back across to the East End. Over there the cholera and typhus which attacked Glaswegians in their thousands during the epidemics of the nineteenth century might have been swept away with the old slums. Plenty of diseases were left to incubate in the new slums which rose to take their place. Those who did not have to endure such awful living conditions could still manage to turn a blind eye to them.

There were others who found them impossible to ignore, people like James Maxton and Helen Crawfurd. Driven by the same passionate social conscience, another was Margaret Irwin. Among the many achievements of her long life, she was the driving force behind the establishment of the Scottish Trades Union Congress in 1897, a body which has always been completely independent of its English counterpart. Never a member of a trade union herself, Margaret Irwin was the STUC’s secretary for the first three years of its existence. Women might not yet have had the vote, but that didn’t mean they couldn’t play an active role in public life.

The daughter of a ship’s captain, Margaret Hardinge Irwin was born in 1858 ‘somewhere in the China Seas’ on board a ship called the Lord Hardinge. After this romantic start to her life, she grew up in Broughty Ferry near Dundee. Her father valued education and encouraged and supported his only child while she attended Dundee University College, part of St Andrew’s University. In 1880 the university awarded her the Lady Literate in Arts (LLA) in German, French and English Literature. Run by St Andrew’s, the LLA scheme operated for 50 years and allowed women and girls around the world the chance to study at university level in the days before female undergraduates were allowed to matriculate and study for the same degrees as men. Students could follow courses at home or take them at their own local colleges before sitting exams set by St Andrew’s in places as far afield as Aberdeen, Brisbane, Cairo, London, Nairobi and New Zealand.

In her early 30s Margaret Irwin moved to Glasgow, where she took classes at Glasgow School of Art and in political economy at Queen Margaret College, newly established for female students within Glasgow University. From then on she dedicated her life to investigating and improving living and working conditions for poor women and their families. She became a recognised and respected authority on the subject. Coming as she did from Broughty Ferry, next door to Dundee and its jute mills, where an army of women toiled to ‘keep the bairns o’ Dundee fed’, she already knew a lot about the living and working conditions of the poor. This may be where her interest in the difficulties facing the working classes started.

For 44 years she was secretary of the Scottish Council for Women’s Trades. As an assistant commissioner to the Royal Commission on Labour, she compiled many reports on working conditions in laundries, shops, sweatshops and among homeworkers. These housewives struggling to make ends meet had even less protection from unscrupulous employers than women in factories and earned ludicrously low wages.

Audrey Canning, librarian and custodian of the William Gallacher Memorial Library, describes Margaret Irwin as being like a modern-day investigative journalist, ‘toiling alone up dilapidated tenement stairs to discover the slum housing conditions of women working for a pittance’. Her investigations and reports paint a vivid picture of just how bad those conditions could be.

Shortly before Christmas 1901 she gave a paper on ‘The Problem of Home Work’ at a Saturday conference in Paisley organised by the Renfrewshire Co-operative Association.

Frequently one finds the home worker occupying an attic room at the top of a five-storeyed building, the ascent to which is by a dismal and dilapidated staircase, infested by rats or haunted by that most pitiable of four-footed creatures, the slum cat. The landings are foul with all manner of stale débris; and the atmosphere is merely a congestion of evil odours. At every storey narrow, grimy passages stretch to right and left, on either side, close packed, is a row of ‘ticketed houses’ …

On every landing there is a water tap and sink, both the common property of the tenants, and the latter usually emitting frightful effluvia. Probably the sink represents the entire sanitary system of the landing.

Armed with a box of matches and a taper and battling with the almost solid smells of the place, one finally reaches the top, and on being admitted, finds, perhaps, a room almost destitute of furniture, the work lying in piles on the dirty floor or doing duty as bed clothes for a bed-ridden invalid and the members of the family generally.

Glasgow started ticketing houses in the 1860s in the hope of reducing overcrowding in the city’s slums. Every house with fewer than three rooms was measured, and it was calculated that each occupant required 300 cubic feet of living and sleeping space. A metal ticket was then fixed to the front door, stating how many people could legally occupy the house. This was enforced by midnight visits from the sanitary inspectors.

By the 1880s, the city had over 23,000 ticketed homes. These housed three-quarters of Glasgow’s population, probably rather more than that once the sanitary inspectors had done their rounds for the night. People were so desperate for a place to lay their heads that the ticketing rules were often flouted. Their unlikely landlords and landladies were in their turn so desperate to make a few extra pence or shillings they were prepared to squeeze in what Margaret Irwin called ‘that unknown and highly elastic quantity, the lodger’. The number of ticketed houses in Glasgow just before the First World War was not much lower than in the 1880s, around 22,000.

While many Glaswegians have fond memories of the camaraderie and warmth of life in the old tenements and of mothers who kept their homes as neat and clean as a new pin and their children well-scrubbed and well-turned-out, there is no doubt that thousands who lived in the Second City of the Empire did so in poverty and squalor. The record is there, in photographs and written accounts.

There were always those who managed to rise above their circumstances. After describing the flat ‘almost destitute of furniture’, Margaret Irwin wrote, ‘However, side by side with the worst of these one finds a little room exquisitely neat and clean and representing a whole world of sacrifice and effort.’ It must have been heart-breaking, hard to witness, but this woman who could have enjoyed a comfortable middle-class life had set herself a task and she would not flinch from it. She was well aware that many of the haves saw no reason why they should worry about the have-nots. ‘It is often said that one half of the world does not know how the other half lives. It might be said, perhaps with equal truth, that one half does not care to know.’

As Audrey Canning emphasises, Margaret Irwin did care to know. Determined that everyone else should too, she was prepared to shout her findings from the rooftops. Her voice reached the legislators at Westminster, helping bring about reforms which made a difference to the lives of thousands. Speaking to the second reading of the Seats for Shop Assistants Bill in 1899 the Duke of Westminster quoted from a report Margaret Irwin had made on shop assistants in Glasgow. ‘My attention has been directed by several medical men of standing and experience, and also by numerous grave complaints from the women assistants themselves, to two causes which, in addition to long hours and close confinement, operate against the health and comfort of women employed in shops. These are – want of seats, and the absence of, or defective, sanitary provisions.’

In other words, they wanted a few seats where they could sit down for a rest now and again, plus a proper toilet. Margaret Irwin recorded a pathetic plea. ‘As has been more than once said to me, “If they would only allow us a ledge to rest upon for a minute or two we would be thankful even for that.”’