11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: mPowr Publishing

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

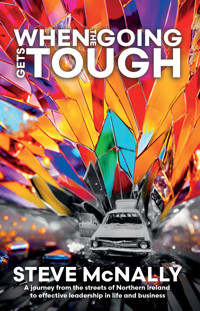

TWISTED STEEL SHATTERED GLASS A FRACTURED FAMILY These are the explosive opening scenes of a journey from passive victim to powerful leadership. From Portadown, Northern Ireland, to the Royal Opera House and the Welsh mountains. From the war-ravaged landscape of Sierra Leone to corporate boardrooms and black-tie awards ceremonies. Your life's journey has different locations, dramatic events and challenges along the way. Steve McNally retells his powerful story with honesty and vulnerability so you can see your own inner journey clearly. His early years navigating The Troubles, then the trials and triumphs of military life, and latterly the challenges of corporate leadership and delights of fatherhood, create a rich window into personal leadership, resilience and strategies for coping with the complexities of both the modern world and your own inner world. Rich with insight and practical tools designed to help you claim and develop your personal leadership and resilience, When the Going Gets Tough, is a true-to-life tale that empowers you to... GET GOING!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 346

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Steve McNally

Steve McNally ©2023

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

First Published in Great Britain 2023 by mPowr (Publishing) Limited

www.mpowrpublishing.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN – 978-1-907282-16-4

Design: Alex Casey–mPowr Limited

mPowr Publishing ‘Clumpy ™’ Logo by e-nimation.com

Clumpy ™ and the Clumpy ™ Logo are trademarks of mPowr Limited

Steve McNally

When the Going Gets Tough

A journey from the streets of Northern Ireland to effective leadership in life and business

Contents

Introduction

One Bomb, Two Murders

Searching for Dad

Burying Dad

Natural Selection

Avoiding Unintended Consequences

Going for Gold

Rubbish In, Rubbish Out

Building Blockbuster Teams

Moments That Matter

Leaving Leaders Behind

Eight Rules for Success

Storytelling—Painting Pictures That Change Mindsets

All Roads Lead to Sierra Leone

Being Dad—Leadership in the Home

Reflections

A Line in the Sand

Introduction

I have been very fortunate to have found a path in life that has brought me so many wonderful experiences, people, and opportunities. There have been challenges, of course, and that is to be expected, but nothing that I have not been able to deal with, and with each one, I have learnt lessons that I could apply when faced with later obstacles.

Not everyone has the benefit of experience for lots of reasons, but we all can benefit from the stories of the experiences lived by those others who are prepared to share them with generosity and love. Although my starting point in life felt at times like rock bottom, I wasn’t stuck there. I want to share my story with you so that you can benefit from my experience. It is imperfectly expressed with generosity and love, and I hope that you find something, however small, that helps you be a better version of yourself, and maybe you can then help someone else do the same.

Ordinarily, six-year-old boys would not be expected to re-member much about other people’s birthdays, but my sister’s fourth birthday will stick with me for the rest of my life. Why? It was 1979, and four days earlier, on 6 March, our father had been blown up by an under-vehicle improvised explosive device (UVIED).

It turns out that Dad’s murder was a test run of a type of device, a mercury-switch bomb, which was later used to kill Airey Neave, the then-Conservative Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary. He was assassinated as he was leaving the House of Commons on 30 March, by the same Irish Nationalist Liberation Army (INLA) cell that killed my father. A successful experiment indeed, but it left a little boy in turmoil.

Maybe that incident, happening when I was at such a young age, significantly altered the course of my life. Who would I have been if my father hadn’t been murdered and was still around as I was growing up?

Where we start does not need to be where we finish. In the following pages, I am going to share my journey openly and honestly, and as you walk with me, I invite you to reflect on your life and consider the challenges and opportunities that it presents to you. What did life look like for me, and how might you take that and use it—for building a better team, developing a leadership offering, being aware of your environment and mindset, or, at the most fundamental level, considering what it takes to be a modern parent or guardian?

For as long as I can remember, I have sought betterment, challenge, change, and even danger, in buckets. Somehow, I have always come through. Was it because of luck, military training, a deep desire to be the person I needed when I was six years old or a combination of all these factors? Join me as I share my story, and you can decide the answer to those questions. What counts more than anything is how you choose to live your life and what factors you allow to determine your outcomes and the people you enlist to help you.

Although there are references to many people and situations in this book, one must not be forgotten. For nearly thirty years of my life’s journey I have had the most important woman next to me. Gillian, my wife, is without doubt my biggest support and supporter. She is an amazing woman, wife, professional teacher, friend, and mother to my two boys as well as being a sister and daughter. I couldn’t ask for more.

Before we dive into my story, let me finish this introduction by saying that some of the people who were with me along the way are no longer here, and there’s not a day that goes by when I don’t think of them. Many of them helped me more than they probably realised, and in doing that—helping this one human being whose words you are reading—they left the world in a better place. I hope that my words and actions help to ensure that I leave the world in a better place as well.

One Bomb, Two Murders

No Ordinary Tuesday

Although 6 March 1979 started as an ordinary day, the events that took place on that Tuesday morning were set to change my life unimaginably and forever. As I sat innocently in a quiet primary school classroom, learning the basics of reading and writing, a loud explosion rocked a neighbourhood in another part of Portadown, the small town where we lived, in County Armagh, Northern Ireland.

Around 1000 hours—that’s ten in the morning to civvies and those not as accustomed to the twenty-four-hour clock as people like me who have served in the armed forces—a 26-year-old member of Northern Ireland’s Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) was driving slowly in the car park of the Magowan Buildings.

As the vehicle began to climb a very slight gradient, it tilted just enough for a tiny amount of mercury, housed in a small glass vessel, to roll onto a pair of contacts, closing a circuit and detonating the UVIED that was strapped to the underside of the car near the driving seat.

The force of the explosion ripped through the car, distorting the metal frame, blowing out the glass and doing its very best to separate the flesh from the bones of the driver.

An Early Start to Adulthood

The man behind the wheel had no chance, and the blast took one of his legs, rendering him unconscious. Sadly, he never regained consciousness and on Monday, 13 March, married father of two, Robert McNally, succumbed to his injuries. That man was my father.

Seven days earlier, when the bomb was detonated, I was just an ordinary six-year-old boy in a classroom, oblivious to the fallout that was coming my way. When the shockwave hit, it turned my life upside down. The explosion that killed Dad, just three days after my sister’s fourth birthday, was responsible for two murders—my father and the wee boy inside me. From that moment, my childhood was over.

An Indiscriminate Killer

Explosive devices don’t discriminate. Unlike a gun, which must be aimed purposefully at a specific target before the trigger is squeezed, a bomb will cause devastation to anyone and anything in the vicinity. To think that my sister and I had been sat in that car only a few hours earlier sends shivers down my spine even today, over 40 years later. Had the killers who planted the device watched to make sure we’d already been taken to school, or was it sheer luck that the bomb was planted later in the morning? What if we had not gone to school for whatever reason? I often wonder how humanity could stoop so low, what kind of people could carry out such attacks, and what makes this sort of thing legitimate in their eyes.

A Bit of Context—The Troubles

For clarity, I will assume that you don’t know about the nature and history of the conflict between Britain and Ireland, and I am going to focus on the most recent period of unrest to give some context to the situation I grew up with in the seventies and eighties.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, most people in Ireland wanted to break free of the country’s ties with Britain; however, a large chunk of those living in the north of Ireland wanted to remain British, and they launched a campaign to maintain Ireland’s union with Great Britain. This led to friction, which is still not resolved even though the region is largely free from terrorist violence, and the community remains divided.

Significant numbers of people on both sides of the argument were prepared to use violence in support of their cause, violence which led to the loss of many lives without ever delivering the solutions the perpetrators had promised the communities who often helped cover their tracks.

Operation Banner

By the 1960s, understandably, frustrations within the Catholic, nationalist community found expression in a campaign for civil rights that drew much of its inspiration from the civil rights marches in the USA. This coincided with the launch of the longest-running operational deployment in British military history. Operation Banner lasted thirty years and marked the start of what has become known as The Troubles, a period that is synonymous with brutality, murder, and hatred and yet also features stories of how the desire for unity overcame the divisions of nationalism and loyalism, exemplifying humanity at its best.

The Troubles caused the death of 3,500 people, including my father. Thousands more were injured, and thousands more were traumatised by violence; however, by the 1990s, there was recognition that violence would not deliver a solution to the conflict and that any effort to find a political answer would only succeed if republican and loyalist paramilitaries were given a voice at the negotiating table.

A divided community

That table, led by our politicians today, remains divided and unable to govern free from the shackles of our history, which means that although free from the levels of violence once seen, we are not moving forward as one community.

Around the time when my father was murdered, we were living in an area of Portadown that was on the front line of the conflict, and I believe that bomb was the final straw of a bit of a haystack. One of my earliest memories is of being banned from playing with my friend Shaun.

Shaun was Catholic, I was Protestant, and our innocence was irrelevant. When I was told that I wasn’t allowed to play with him anymore, I couldn’t understand, and it hurt me deeply. Sadly, it didn’t take long for me to realise that the end of our friendship was only the beginning, and many other restrictions would follow that had nothing to do with me or my beliefs and values—symptoms of the times we were living in.

A Downward Spiral

Very shortly after being banned from spending time with Shaun, our dog was taken and killed. It was becoming increasingly clear that we were no longer wanted in the area as the demographic continued to change at a raging pace. The situation continued to escalate, taking a more sinister and targeted turn when a hoax bomb was placed at the front door of our house. I vividly remember being taken out of the house in a blanket by my uncle and moved to a safe location while the Army dealt with the incident. Little did I or anyone else apart from the perpetrators know that this was part of a wider plan to monitor the Army’s bomb alert response times and procedures.

Although it was very difficult for a six-year-old to understand what was happening around us, I was well aware that we were not safe anymore; but what could I do about it—I was just a wee boy. My mum understood what was happening and moved us out of the family home when she could see the direction things were going. From antisocial behaviour to killing the family pet to bringing the bomb squad to our home—what next?

Wrong Place, Wrong Time

My father was defiant, but he was a soldier after all, and he may have unwittingly caused some of the attention we were getting by being less than discreet when coming to and from our home. I later discovered that not only was Dad indiscreet, but he actively antagonised the local members of the paramilitary group, the INLA—the same people who went on to plant the car bomb that killed him.

That bomb, a switch UVIED, used what has become known as a mercury-tilt switch as a fuse. All it takes is the slightest vibration, and a small amount of mercury will connect the two contacts in a circuit, and the UVIED will detonate. The INLA was carrying out a test run of the device when they killed Dad, who happened to be a convenient target right on the organisation’s doorstep. The person they were most interested in assassinating was Airey Neave, the then-British Shadow Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

On 30 March 1979, a cell of INLA members used the same kind of mercury-tilt switch UVIED to murder Neave, by fixing the device in the exact position on his car as they had done to my father’s vehicle—on the underside of the car, near to the driver’s seat. He died shortly after being admitted to hospital.

Flashpoint Memories

The day I found out that my father was dead, I was sitting in the chair at the window in the corner of the living room of our new home, a flat in another part of Portadown. I liked sitting there because it gave me a cracking view of the park and the trees that I would come to love climbing in and, bizarrely, collecting snails from. We were still settling in, so I didn’t know anyone and wasn’t sure why we were there or why we had not seen Dad for eight days. Those questions were about to be answered!

Mum came into the room, and my sister joined me in the corner seat, and that’s when she explained what had been going on and why we hadn’t seen Dad for so long. Then she shared the horrible news that our father was dead, and we would never be able to see him again. I don’t recall her exact words. Maybe I blocked them out. What I do remember, which may seem hard to believe or strange to others, is the overwhelming feeling of unfairness that this had happened to me, my family, and my father.

When we experience intensely traumatic or shocking moments, sometimes we block out the most painful bits to protect ourselves, but what’s left remains etched in our minds forever as flashbulb memories. The flashbulb memory created by the news of Dad’s murder was powerful and big enough to envelop mundane events from the week before and after, including my sister’s fourth birthday.

Everything about that day is as raw now as it was then, but you may be shocked to learn that the trauma for me was not so much about finding out my father was dead; that didn’t come as a surprise, and I even half-knew that was going to happen.

Over the years, perhaps since that moment, I have honed an instinct for situational awareness, often visualising what is coming next just before it does. Perhaps, subconsciously, I had already developed some skill in that area and was absorbing the atmosphere of Portadown without consciously understanding what the fuss was about. Intuitively, I could sense meaning from the world around me.

Man of the House

The news that Mum imparted to me that day was absorbed and processed, at least superficially, and I moved on emotionally very quickly. Losing a parent at such a young age leaves a massive hole that the person who is left behind may not be aware of until adulthood, if ever—the sense of abandonment and the loss of the person they looked up to for guidance, to name a couple of big issues; however, there were more practical consequences that I knew I would have to adapt to.

Dad’s death marked the abrupt end of my childhood and the death of the wee boy inside me. I vowed to be the man of our house and to protect my sister, something which I failed to achieve on several occasions and struggled to forgive myself for in the decades that followed. I’m going to revisit forgiveness later.

There are two school years between me and my sister, and this meant that I was always close to keep an eye on her when she needed me or even when she didn’t know she needed me. This dynamic continued and went on to form the spine of our relationship for years to come.

Mum appeared to move on from the murder of her husband as quickly as I moved on from the death of my father, but I cannot know for sure. It’s the conclusion I came to, based on the fact that, once we had been told about his murder, the topic was never discussed again. So what? Not talking about stuff is something that has developed into a recurring theme in our family, and that has left many unsaid words and allowed gaps to grow in the grieving process, especially for my sister, Cheryl. Only the other day, when I was talking to her about this part of the book, she said, ‘I wonder what he would think of me now,’ with a tear welling up in her eye—over 40 years since he passed away.

Cheryl has her own business and three lovely children but has, at times, been unhappy with how her life has turned out. I can’t help but think that if we had spoken more about our father, and if my mum had stepped up and been emotionally courageous enough to talk about him in a child-appropriate manner and lay on me and Cheryl with the kind of affirmations that a father might lay on his children, we would know what he would have thought of us; not for sure objectively, of course, but we would have felt certain because the programming would have convinced us of it. In the grand scheme of things, feelings are sometimes more valuable than facts, especially for young minds when they are developing.

Peeling the Onion

Much remains unsaid in our immediate family but not for long; peeling this onion is at the top of my hit list. I am fortunate that my sister and I have a close relationship and can talk about the challenges we shared as children. I continue to be her big brother which, second only to being a loving husband and father, is my most treasured role. For many others in my family, there is a wall of silence.

We moved home again shortly after the news of Dad’s murder, to a house that was in very poor condition and felt grubby and dirty. I could not understand why we had moved so soon and, of course, did not get a reason; however, the place was soon looking spic and span and, actually, the cul-de-sac we moved to was great, full of kids of our age, and we quickly settled into what felt like a very safe place to be. We were not alone for long, though.

A New Man of the House

A new man arrived in the house, and he was there to stay. This didn’t sit well with me as I was the self-declared man of the house, and I immediately threw myself into a battle for power. I was eight. Who did I think I was? I knew who I was, and I was determined to play my role, which often meant being a bit disruptive as this new man, who shall remain nameless as there was an incident that makes naming him difficult, issued instructions in the house.

Mostly, it was his presence that annoyed me, so he didn’t have to do anything to earn my wrath, and he didn’t appear to be a bad person. Sometimes, I allowed myself, the little tyrant, to enjoy his company. After all, he had become almost as much a part of our life as Dad.

Time is a funny thing, and how we experience it is entirely subjective. It bends and distorts. We didn’t have long with our father, six good years, but because we were so young, it felt like a fleeting moment and very few memories exist. Meanwhile, time was passing slowly with our new lodger, and he’d soon been with us for as long as my sister had been alive when our father was murdered. Time with Dad was shrinking all the time as a memory, while time with the house guest was steadily lengthening. We were used to him.

Almost as violently as our father’s death, the new man was gone! What had happened? Given the lack of talking that I’ve already spelt out, we got a very paltry, ‘He’s gone.’ Even though it turns out there was a long list of reasons for him to be gone, we did not get to hear any of them at the time. Of course, I thought I had got rid of him, that my mission to oust him was accomplished, so I was clear to reclaim my man-of-the-house role again—and legitimately, as I was always there when the other men who showed up were not.

Our childhood was full of fun and laughter despite what was happening around us in our house. We had lots of friends, I had discovered the joy of BMX riding, and I was not far from my grandmother’s house. I was very close to Gran and used to enjoy hanging around with her in the garden, which was full, from hedge to hedge, with the vegetables and soft fruits that she grew every season, even in not-so-sunny Northern Ireland.

All was well for a while until my man-of-the-house role looked likely to become threatened again, or so I thought. New man, same offer—nothing. I was eleven by this stage and a pretty forceful young kid, and I made him know how I felt and never let up. To his credit, he stayed and married my mum, so I had, in title only, a stepdad—but not in spirit, and I never once acknowledged his place in my life. This was partly due to his weakness as a man, based on my perception of what I thought it would take to be a good dad. Of course, this was based on my imagination, images of heroes that I was watching on TV, the likes of Steve Austin in The Six Million Dollar Man and Colt Seavers in The Fall Guy, both played by Lee Majors. Funny, now that I think about it, but I have continued to model my behaviours as a dad on those early perceptions that I conjured up—I do not run in slow motion like Steve or jump from a tall building like Colt, but I set high standards for myself as a dad.

The new imposter failed to impress me in any way, and the situation was made even worse when we moved again to where he was from. Another grubby house and miles from my school and friends; I was pretty pissed off it was fair to say. I didn’t move school and stubbornly went about building my own life as the one that was being built for me did not appeal. By then, I was thirteen, and I was moving on and paving my own way.

Looking For an Exit

Northern Ireland was still very divided and I, like that little boy who did not understand why he could not play with Shaun, was not happy with being labelled as one or the other in the religious mayhem that still defined the streets where we lived and played. At fourteen, I decided that I was not going to live my life with this choice and made a commitment to leave Northern Ireland at the earliest opportunity.

There was not a lot of prosperity in Northern Ireland at the time and coming from my extremely working-class, sometimes not even working background, the escape route did not look too easy. One newspaper article jumped out at me—Army Careers. That was it, my mind was made up, and everything I did from that moment was gearing me towards joining the Army at eighteen years old.

I would not be confined or defined by the situation in Northern Ireland. I would set my own path.

In one moment, because of one advertisement, a fuse within my heart detonated, an explosion followed, and I was set free. The goal was set. All that remained was the execution. I got a part-time job, did what I needed to at school (just about), and prepared for life in the British Army.

As I write, it is 27 October 2022 and, quite fortuitously, today marks the launch of the Royal British Legion Poppy Appeal and the start of my journey to commit my thoughts to words on a page. My whole life has been influenced by the military, legitimately as a serving officer, and illegitimately as a victim of The Troubles in Northern Ireland, like so many others. My father was a soldier, my grandfather was a veteran of World War Two, and growing up in Northern Ireland in the 1970s meant violence and conflict were never too far away. Perhaps, I was destined to become a soldier.

In this chapter, I have given you some glimpses of my childhood and the world I grew up in. Over the course of this book, I am going to show you how those experiences have helped me adapt and grow in later life, but the timeline will not be linear.

I will try to balance academic insight with my experience to help articulate the message so that it is not all hot air and history, and I hope you find what I share useful personally, for a friend or family member, or even for someone in your work or business life.

Some of my experiences have been challenging, some plastered with extreme violence, some funny, some very special, and some deeply sad. All of them have helped build a better version of me, a version that I could never have hoped for, given the start I had and nearly didn’t have considering the circumstances on that fateful morning of 6 March 1979 when I could have been in that car when the bomb exploded.

We have all been programmed by our upbringing to some degree. Like other biases such as racism, we are not born with these shackles, and we can, with acknowledgement and work, shake them off.

When the going gets tough, what do the tough do?

Strap yourself in, and I will help you find the answer or at least give you some tools to kick the journey off. Remember that a march of a thousand miles starts with the first step. This chapter was your first step. Now, it’s time for the next

.

Searching for Dad

Losing my father so violently, both in how he was killed and its suddenness, left me with a huge hole to fill. Fathers are to young boys as satnavs are to those navigating a route to somewhere they’ve never been. Children can feel lost without their parents and boys look to their fathers for guidance. I’ve had a lifetime to consider how the death of my father impacted me and, in this chapter, I am going to introduce, explore, and share some of the main themes relating to fathers, sons, and father-son relationships.

It’s funny how often we do things without knowing we are doing them. When I lost my father, I immediately felt that I had a responsibility to fill his shoes. What a load of bollocks! I was barely out of short trousers, so who did I think I was? And that’s the point: At that age, I didn’t know who I was. I didn’t have enough time under my belt to have a meaningful sense of who I was and as a young boy, I wanted—no, needed—a father to show me. Given my determination to be the man of the house, the sooner I could get that guidance the better. I needed it desperately.

A deep emotional connection to experiences and stories is our best learning medium. Who would be there to let me make the mistakes that would enrich me as I matured? Who would curate the stories that would shape me? Under whose watchful eye was my journey to unfold?

Psychological Literacy

Of course, I am no longer so naive as to think that is the way all father-son relationships turn out. It is, however, not too unrealistic to want a role model, someone who loves us unconditionally but will guide us even when it means chastising and correcting poor behaviour. This is as relevant now as it has ever been. Today, we understand the needs more than ever with the abundance of information available to us; indeed, you could argue that we all should be able to achieve psychological literacy on a personal level on our own.

Psychological literacy is, in its most basic form, an understanding of how to be insightful and reflective about not only one’s own behaviours and mental processes but that of others. It’s easy to see how this is relevant to the context of a boy learning how to be a man through the guidance of their father and in many ways, this is a tried and tested formula. We need only to look to the animal kingdom, be it the art of the hunt or even survival from predators or just in good old figuring out how to be.

While I knew that I yearned for a father figure, I was very much getting on with being me. On reflection, I did not legitimise instruction from the adults around me at home, including my mother or any of the men who became part of our family unit, not because I was not able or willing to but simply because they did not make the quality line that I had set. Outrageous when you think of my age and position in the family unit at that stage in my life, but apart from my sports coaches or the teachers who I believed set good examples of what it was to be a strong male, I pretty much ignored every other adult.

Now I understand that I empowered myself unless I empowered others by deeming them worthy enough to be considered as any kind of mentor, guide, or role model. This was a risky strategy as the checks and balances had constraints. Those whom I empowered had little time to create and deepen influence, and they did not know I had charged them with this responsibility, so any failings on their part would be spotted and magnified by me without them knowing how important their behaviour was. Even if they had been aware, the only opportunity they had to lead was while I was with them in the classroom or on the rugby pitch. The rest of the time, I was a law unto myself, ‘leading the self’.

Men in the Home

The men/potential fathers who came in and out of my and my mother’s family life, even the one who hung around the longest but (to be fair) added the least value considering the timescale, were, unbeknownst to me, building my subliminal understanding of psychological literacy.

Some theories say that to be truly psychologically literate, there are nine attributes we need to have and display. As well as being insightful and reflective, being psychologically literate includes:

Psychological knowledge—the state of being familiar with something or aware of its existence, usually resulting from experience or academic study. My understanding, certainly the knowledge I am sharing within this book, is from experience.Scientific thinking—a type of knowledge seeking that involves intentional information gathering, including asking questions, testing hypotheses, making observations and collaborating with evidence. In today’s world, data is key, and you will often hear the call for data-based decision-making.Critical thinking—the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skilfully conceptualising, applying, analysing and evaluating information gathered pre decision-making or planning.Application of psychological principles—applied psychology is the application of psychological principles to solve problems of the human experience and can be applied anywhere from the workplace to the battlefield.Ethical behaviour—ethical behaviour is what guides us to do the right thing, tell the truth or simply do no harm and help when we can. This has scope to be manipulated depending on our beliefs; my measure is about how my ethics help me make decisions that create positive impacts and importantly avoid unjust or negative impacts. This is the tricky one on the list for sure.Information literacy—This is particularly important for those who have the power to make decisions, especially if they are on behalf of others. It is the ability to find, evaluate, organise and use information in all its formats to make good, informed decisions. In my military career, this was very important as the result of a bad decision could mean the loss of life. Information is king!Effective communication skills—This is the simplest aspect of psychological literacy to understand but can be the most difficult to achieve, especially if, like me, you have had to socially mobilise yourself, had an education that is less than perfect or culturally you are not confident in expressing yourself; all of that is before we add in the additional challenges of introversion or neurodiversity.Respect for diversity, equality, and inclusion—This is not just having respect and acceptance but actively seeking out diversity across its many considerations, not just the obvious gender or race, offering equity, not just equality, and being inclusive in a manner that gives everyone a voice.We are all aware of these principles to some degree, and I am sure we can all recognise some of these in ourselves and indeed could admit to needing to work on some or all of them on some level. Not so for a wee boy, however, who was lost in who to be and how to be it. Although I was values-driven from an early age, I wasn’t self-aware enough to know it.

At a time when I was trying to learn how to be and who I wanted to be, from the age of seven to fourteen, the only models of masculinity I had in the home were poor. What other competencies would I need to acquire to break clear of their terrible examples of behaviours, lack of courage, poverty syndrome and downright laziness? When I say laziness, I don’t just mean that in its simplest form. I am talking about not taking steps to be better by refusing to accept where we are and striving to reach where we could be—the cycle of attracting the minimum and blaming the environment for it.

Learning to be is one of four pillars of a structure first outlined in a report called The Treasure Within, which was submitted to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) by the then-chairman of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-first Century, Jacques Delors. It is a system I have used over the last few years to promote a change in approach to how we train young people coming into the world of work, specifically within the field of professional services, which is where I find myself now. This is work that I have been fortunate to have won recognition and awards for, but, boy, do I wish I knew then what I know now, back when that wee boy needed to know how to make sense of what was happening to him. Well, it’s never too late!

The other three pillars are learning to be together, learning to know, and learning to do. For now, I’d like to focus on learning to be, and the part that played in helping to shape me into the person I am today.

Learning to Be

While I searched for a father in my early years, I didn’t realise that what I was actually searching for was psychological literacy. I didn’t need a person, but if I were going to benefit from having someone to guide me, their persona would have to reflect mine. What I needed was simple—an example of my values and an opportunity to be guided on my path to learning to be.

Faith, while not a theme of this book, is something that we all can benefit from, regardless of what each of us uniquely believes. I became aware of something greater than myself at the age of around ten and took myself off to a place of worship for me to explore. My relationship with a higher power is something I have never quite mastered even as I try a new place of worship today, but what I do believe is that the connection I feel is real and the values are close to my heart. Perhaps, this is where my father has always been—there, right in front of me—but like many a child, I have denied its presence and therefore missed out on the benefit of its stewardship and love.

Although I missed many opportunities, either because I didn’t recognise them or indeed because I ignored them, thinking I knew better, I am truly grateful for one that didn’t escape me when I was a teenager. It was a chance that arose spontaneously and not by design, at least not by my design, when, at the age of around fourteen, I got a part-time job in a fish-and-chip shop. It was not a glamorous opportunity by a long shot but one that I grabbed with the enthusiasm of an Olympic athlete accepting a gold medal.

What unfolded over the next four years that I worked there is the story of how I truly learnt to be. Like any learning journey, the enabling conditions are critical to success, and if we are ever to achieve transformational learning or change in a cultural growth or transformational programme, the conditions must first be right, not perfect. The world is and always has been complex, and technology seems to be moving at its fastest pace every new day. There have been many technological revolutions, but the digital transformation that the world is experiencing today is perhaps one of the most fast-moving and omnipresent ever.

Learning to be is not just a personal journey, but it is also about acquiring the competencies needed to succeed. For the benefit of this book, I am defining competence as the ability to meet challenges in any environment in a complex landscape. For any individual to achieve that means learning through the experiences of engaging with complex challenges that not only motivate them but also benefit the wider stakeholder community. Working in the chip shop was about to become my most enriched learning environment to date on many levels.

A Version of Dad—Keith

If I thought my search was about finding a father, I had achieved the mission, at least as far as finding a male mentor who I looked up to and who reflected my values in everything that he did was concerned.

I was instantly drawn to Keith, the owner of the fish shop, but he was not so drawn to me at the beginning! He did not want teenagers on his staff and although he agreed to give me a chance, this was with the expectation that I would probably fail to impress. Little did he know that once given the chance to do something that I wanted, I would be like the dog that refuses to let go of the bone, and he had no idea what I was capable of.

Keith was an exceptionally hard-working man and although it was only a small, local fish-and-chip shop, he had introduced lots of innovation that I don’t think he fully appreciated but I did. I delivered on every level and sought to exceed expectations. When he asked me to do one thing, I did two; when he set a standard, I went a step further; when there was space in the rhythm of the customer flow, I looked for an opportunity to improve things, doing small tasks such as cleaning machines that were already clean by most people’s standards but not mine. I set high standards, and he kept giving me the space to grow. Keith trusted me with something dear—his business and customers.

I shadowed him, but he didn’t know I was doing it or at least he didn’t show it, and I observed everything he did, keen to demonstrate continuous growth in my competency and to show that I should be trusted to take on other responsibilities.

In a very short time, I was working 32 hours a week in the shop, which was unusual for a fourteen-year-old, but I can now see that it was as destructive as it was productive. Why? My time should have been more evenly balanced between friends, socialising, and simply being a child. Although I was highly capable, I wasn’t spending enough time in school because I was poorly motivated by its academic offering, and being with the family unit was the last place I wanted to be.

Leaving Home

Home is the place where I should have been guided, and I think Mum could have and should have intervened to help me gain more balance. It was not to be, and I would have been difficult to persuade anyway. Keith could have done it, but why would he when he had an increasingly competent right-hand person to help him run his business? That is where Mum could have applied pressure without me even knowing, but, alas, she offered no guidance, no advice, no interest or even recognition of the need of a fourteen-year-old to be guided and nurtured through the difficult teenage years.

If I am going to be brutally honest about it, I may as well have left home at fourteen because mentally, I had entered the world of adulthood and independence under the stewardship of my boss, even though I was still sleeping at the family home. Keith provided me with an example of what the rewards of hard work can bring, he gave me the opportunity and trust to push myself, and he gave me rewards for succeeding in the form of affirmation and financial bonuses.

In later years, Keith told me that he never had an employee that matched what I brought and that I had helped him be a better version of himself when he was working with me. That is the most powerful piece of professional feedback I have ever had, and it came in response to the efforts of a wee boy between the age of fourteen to eighteen. Words endure history, so be careful with yours!