Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Here, in a new edition of her first book, the late Joyce Latham looks back on her childhood days - the 1930s and the wartime years - in a way that will bring memories flooding back for readers of her generation. I many ways hers was a typical Forest upbringing - one in which poverty was softened by the warm and close-knit support of friends and relatives, but in other ways her life was anything but ordinary, and some remarkable reminiscences are woven in among her accounts of everyday events. Joyce was born in Westbury workhouse, the lovechild of a servant girl - and if she had not been rescued by her grandmother, the beloved Mam who dominates these pages, her life story would have been very different. Here, too, are tales of crossing the frozen Wye on foot at Symonds Yat, of an outstanding bid by her schoolteachers to adopt Joyce, her first hurtful taste of prejudice against people of her background, and an old uncle's first-hand tale of the Union Pit disaster of 1902, a tragedy that left its mark on the Forest for decades. You will find many of Joyce Latham's verses in this book too, but most of all you will gain new insights into her perspective way of looking at the world, and find your own love for the Forest of Dean enriched and stimulated by hers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 197

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Where I Belong

A FOREST OF DEAN

CHILDHOOD IN THE 1930s

JOYCE LATHAM

THE HISTORY PRESS

For my dear husband, Bob, our children, Michael, Sally and Martin, our grandsons, John and Paul, and in affectionate remembrance of my beloved Mam without whom this book would never have been written.

First published in 1993

This edition first published in 2007

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

Copyright © Joyce Latham, 1993, 2007, 2012

Edited by John Hudson

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8026 8

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8025 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

1 Born in the Workhouse

2 Mam and Dad

3 Barn House and Edge End

4 On the Move Again

5 Washday Blues

6 The Spring Well

7 Seasons of Magic

8 Dares and Dangers

9 Uncle Jim’s Tale

10 Blushing Bridesmaid

11 Meet the Folks

12 And So to School

13 The Two Joyces

14 2½ Brothers and Sisters

15 Into the Big School

16 Song and Dance

17 Old Olive’s Bombshell

18 Love’s Young Dream

19 Going Out in Style

20 A Forest at War

21 Christmas Star

22 Bell’s Belles

Acknowledgements

My heartfelt thanks to family and friends for their help and encouragement in my first attempt to write a ‘proper’ book; the many Foresters and ‘Vurriners’ who have been kind enough to wish me well; John Hudson for his sympathetic editing; Alan Sutton and staff for their skill and hard work in making this book my very special dream come true; and my son, Martin, for being so supportive and for producing the lovely book jacket which projects exactly the image I had hoped for. Thank you all.

I would also like to thank the following for their kind help in providing the illustrations: John Saunders for the pictures on pp. 20, 27, 52, 64, 80, 113, 118; Bill (Buller) Gwilliam, p. 22; Bob Latham, p. 79; Alec and Molly Baldwin, pp. 58, 59, 63, 69, 71. All other photographs are reproduced by courtesy of the Dean Heritage Museum.

NOTE FROM THE FAMILY

Sadly our mum, Joyce Latham, died on 27th February 2007. Her three children, Mike, Sally and Martin, would like to thank everyone who made her books a great success the first time around. We hope she will be remembered with great fondness for her lovely prose and poetry and hope those who read her books will find them inspirational. She loved life and the beautiful Forest of Dean where she lived. She never had a bad word for anyone and was great fun to be around, always making people smile and touching the lives of so many. She was a wonderful mum and friend to Mike, Sally and Martin, a precious nan to John and Paul, much loved by Lucy, Cilla and Liana, and was nanny Joyce to Jeremy and Zoe. She was very proud of her great-granddaughters Tasha, Lily, Scarlett and Ione. We all miss you so much and you will always be in our hearts. Rest in peace, the best mum anyone could ever have.

CHAPTER ONE

Born in the Workhouse

The Forest of Dean, locked between the rivers Severn and Wye, is known as a close-knit world of its own, and one that keeps its secrets. When I was born in the early 1930s almost every family in the little working towns that were scattered through the woodland clearings had one or more menfolk down the coal pits, and stone quarrying, farm labouring and forestry accounted for most of the other jobs available to men. For girls leaving school the choice was even more limited, with many being packed off at the age of 14 to go into service in Bristol, Gloucester, Cheltenham and even as far afield as London. My mother Elsie’s destination was Bristol, where she found a job as a scullery maid, the lowest of the low. All the dirtiest work of the household was heaped on her, cleaning the ashes from the fireplaces, black-leading the kitchen range, scrubbing the floors. After a couple of years there, she returned to the Forest and her parents with a secret of her own; she was pregnant with me.

My grandparents were very poor, and they must have been in quite a state when confronted by her. Needless to say, Elsie’s boyfriend had long since made himself scarce. Luckily for her, her parents did not turn their backs on her, but my gran made it quite clear that the baby would have to be adopted.

In those days there was only one place of confinement for girls caught in my mother’s position, and that was the nearest county workhouse. Ours was at Westbury-on-Severn and it was there, on 16 March 1932, that I arrived into a cold and uncaring world. My mother had a bad time of it, suffering a haemorrhage that nearly cost her her life. I was three weeks old before she was strong enough to go home, and by then she had consented to my being adopted as soon as suitable parents could be found. My gran managed to find the fare to come and fetch her, and many years later she told me of all that happened on that fateful day.

‘I remember it were bitter cold,’ she said. ‘I give one o’ the nurses a vew clothes for our Elsie to change into an’ ’er told me ta take a seat in the waitin’ room. It were a grim sorta place, thic workhouse, all gloomy an’ bare walls, no pictures or flowers about ta cheer anybody up. I ’adn’t bin sat there long afore a Sister popped ’er yud round the door. “You must be Elsie Farr’s mother,” ’er said, comin’ over ta me, an’ I replied: “That’s right, I be waitin’ ta take ’er wum.” “Well, now, Mrs Farr, I’m sure you’ll be wanting to see your little grand-daughter before you go, won’t you?” said the nurse. “It’ll be the only chance you have.”’

At this, my gran apparently tried to wriggle out of it: ‘I’d rather leave things as they be, Sister. Better all round, I reckon.’ But the nurse, well versed in the ways of human nature, would not be put off quite so easily, and soon had my gran trailing behind her into a ward full of little cots. She walked purposefully towards one at the far end of the room, and before my gran knew much about it she had thrust me into her arms saying: ‘Here you are, then. I’ll leave you to get acquainted.’ ‘No harm havin’ a quick peep, I s’pose,’ thought my gran. ‘Won’t make no difference now, any road.’

The rest, perhaps, was inevitable: ‘Well, o’ butty, I pulled back the blanket an’ there was thee big brown eyes starin’ up at me, just like saucers in thee little white face. I noticed a vew wisps o’ ginger hair cocked round thee ears, an’ what wi’ no tith, bald yud, an’ arms an’ legs as skinny as bean sticks thou’s reminded me o’ thic there Gandhi bloke after one o’ ’is fasts. Poor little dab, I thought. It don’t seem like nobody do want tha; chunt thy fault, didn’t ex ta be barn, after all, did tha, o’ butt?’

My gran’s warm, generous heart overflowed with love and pity. By the time Sister returned I was wrapped up snugly in one of the cot blankets and cuddled down in her plump, motherly arms. ‘’er’s comin’ wum wi’ me,’ she declared, defying the nurse to argue the point. Not that that was really necessary. ‘I had a feeling you might change your mind when you saw her,’ said Sister. ‘She’ll be much happier brought up with her own flesh and blood.’ From that moment on my gran became my own dear Mam, the best in the whole world, and that is the way I shall refer to her through the rest of this book. I certainly have a lot to thank that nurse for; she must have been my Fairy Godmother in disguise, for she ensured that when I was found in that Forest workhouse, it was by someone who would give me a loving and caring family. This poem, written a few years ago, can only begin to reflect my feelings of gratitude to my Mam.

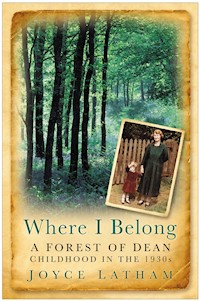

Joyce with her gran – the Mam of this book – at Barn House,Hillersland.

The Lovechild

I started off life in the workhouse,

A lovechild of shame, all forlorn.

Me mam said she’d have me adopted,

She wished I had never been born.

Then gran came along on a visit,

Just one little peep was her aim,

I’m told that a glance was sufficient,

And then she was heard to exclaim:

‘Oh, look at the poor little creature,

All eyes an’ so skinny an’ white,

A vew wisps o’ hair, almost bald, I declare

– I’ll keep her, the dear little mite.’

So that’s how my fate was decided,

Perhaps there is someone above,

No longer an unwanted lovechild,

This child was surrounded by love.

CHAPTER TWO

Mam and Dad

It must have been quite a shock for my grand-dad, who of course from that day on was simply our Dad, when three of us arrived back home instead of two. Mam told me years later that he was surprisingly good about it, in spite of the fact that he was over sixty at the time and had doubtless been looking forward to a bit of peace and quiet in his later years. My grandparents, after all, had already brought up four children of their own: Doris, the first born, crippled in one leg, but hard-working and always cheerful; my mother, Elsie, attractive with beautiful deep auburn hair; Violet or Vi, pretty, full of life, and always surrounded by admirers; and Bill, the last, tall and well built, with a mop of curly hair, and inevitably the apple of Mam’s eye.

By the time I arrived on the scene all but my mother had left home, so poor old Mam simply had to start all over again. Elsie doubtless helped her for the first year, but after that she married a neighbour, Bill Sollars, and went to live with his family just a few yards up the road. Bill and his folks were always good to me – but of course, I did not see them as my immediate family, so by the time I was old enough to take notice, it was just Mam, Dad and me. I had been christened Agnes Joyce Farr, the first in honour of a nurse at the workhouse who had been kind to my mother. Luckily, Vi persuaded Elsie to give me Joyce as a second name, and that’s what I’ve been known as ever since.

From my earliest days my mother was Mammy Elsie, later simply our Elsie, since she was always more like a sister to me than anything else. So were the other two girls, and their brother was our Bill. It made me feel I belonged more, somehow, but Mam made sure I was not kept in the dark about my real relationship with anyone. Since I had grown up with the truth I was not suddenly confronted by it, and that surely is right. I think it is a great mistake when an adopted child has to find out about it the hard way in later years.

Mam and Dad with their natural family – Bill, Doris, Elsie and Vi.

Our Mam was one of a large family – the youngest, and tragically so, for her mother died when she was born. She was brought up by an aunt, a widow with no children of her own, and who knows what part that fact played in her taking me to her heart that day in the workhouse at Westbury? Not that she had a cosseted childhood. Her aunt was very poor, and had to toil hard for a living. Mam could remember being taken into the fields when the frost was still on the ground to pull turnips, parsnips, swedes and potatoes in season. Every year she and her aunt went off to Herefordshire for the hop picking – but she reckoned that was almost like a holiday, with everyone gathering round camp fires at night to cook their meagre meals. There were lots of gypsies among the casual workers, and she soon made friends with their children, and came to admire and respect them. She learned that far from being dirty, real Romanies were spotless in their personal habits and the way in which they kept their caravans. They’d put most of our lot to shame any day, she would say.

Another regular journey in season was the long trek to Trelleck, on the far side of Monmouth, where they would pick whinberries all day. Then they would struggle back home in the late evening carrying the baskets of fruit, only to be up early the following morning to sell them at the open market at Speech House, deep in the Forest. There was never much time left over for Mam to play with other children, and there was certainly no money for toys.

Two well-off spinsters ran a small private school for the poor of the parish at the Scowles, a hamlet not far out of Coleford and about a mile from where Mam lived, and when her hard-pressed father could afford it, he would give her a penny a week for a little education. It was not an ideal arrangement, but she somehow learned to read and write ‘enough for the likes of her’, as one of her teachers was once heard to sneer. After that, it need hardly be said that as soon as she was 14 she was off into service; her first ‘place’ was Sunny Bank House at Sparrow Hill, near Coleford, which is still there today. She often told me how badly the house maids were treated there, especially by the cook; she reckoned that while the girls went hungry, living almost entirely off left-overs, the cook’s fat old bulldog would dine off great slices of freshly-cut ham. Such tales were common, of course, around the turn of the century, with so many servants treated as less than human. The mistress would often hide coins around the house, under mats or behind furniture. If they were found and handed back, well and good – but if any maid gave in to temptation, she would be sacked on the spot. This meant the poor girl would have no reference, and would have great difficulty in finding another post. The only real escape was through marriage, but many young girls who rushed into this option found themselves slaving away as hard as ever, with the added burden of a drunken, violent husband, babies arriving in quick succession and poverty far more pressing than in their single days.

Mam in her younger years, aged sixteen.

More than likely our Mam thought of marriage as an escape route from both service and her aunt, but the man I grew up to know as Dad was not the most brilliant choice of husband. He was all right when he was sober, but everyone dreaded the sound of his footsteps as he returned from the pub. He often gave the children a beating for some excuse or other, but he never laid a hand on Mam; all bullies are cowards at heart, and he probably realised she would give as good as she took. Nearly every pay day she would have to go out late at night looking for him, and would find him lying somewhere drunk, all the money gone. That is why she took in washing to see us through the week – and why, like so many women in the same boat, she hated drink with a passion it is hard to understand today.

She was very house-proud, and the little bits of furniture she had were always gleaming from Mansion Polish and elbow grease, a magic ingredient which always intrigued me; did it come in jars or tins? When she was elbow-deep in soap suds or ploughing through a great pile of ironing, she would often burst into song with a strong, quite pleasant voice; goodness knows, she had little enough to sing about. Every springtime would find our home upside-down and Mam busy colour-washing the cracked and bumpy old walls with yellow ochre, and whiting the ceilings and pantry with lime. This gave the house a faintly antiseptic smell, which I didn’t dislike. She could never afford new curtains, so the old ones were often given a fresh lease of life with Drummer Dye. The trouble was, once she got started she never knew when to stop; cushion covers, bedspreads, table cloths and much else besides all went into the old bathful of dye, and it’s a miracle the cats and dogs didn’t take a dip, too, in Mam’s sudden urge to have everything to match. ‘Eh, our Joyce, I be feelin’ real poorly,’ she would say, every year, with a twinkle in her eye; and every year I’d fall for it.

‘Oh, Mam, what’s the matter?’

‘Well, o’ butt, I’ve bin a-dyein’ all day.’

She had always been well-built, but by the time I arrived she was going on for sixteen stone, which made it a tight squeeze in our tiny kitchen. Her hair had gone grey many years before, and she always wore it in two plaits around her head unless there was a special event coming up, perhaps a trip to the seaside or a Mothers’ Union tea. This called for a bit more of an effort; her long grey locks would be let out of their restraining braids, brushed and combed for ages and then rolled up in dinky curlers. Her only setting lotion was a few drops of vinegar in water in a small jam jar, in which she dipped her comb. The curlers were left in place for a few hours and then taken out with great care, to leave fat little grey sausages. These were covered in a fine hairnet, and the lot was secured with hairpins. Our Mam would then peer into our little swing mirror and push and prod her hair around until it was arranged to her satisfaction. Arrayed in her one good frock and coat, she would then take minutes to place her freshly decorated hat to best advantage, secure it with her black-tipped hatpin and be off. You could see she really thought she was the cat’s whiskers. These outings happened only once in a blue moon, so Mam, bless her, squeezed every ounce of enjoyment out of them.

Mam in her twenties.

On Saturday afternoons, if she could afford it, we sometimes visited Coleford Cinema, heading for the cheap seats, known to one and all as the Chicken Run. In fact they were not particularly cheap, a shilling for adults and sixpence for children, but for a couple of hours Mam was able to escape to worlds far-removed from her poverty-stricken life. Her particular favourites were two stars from the other side of the ocean, Spencer Tracy and Gene Autrey – plus George Formby, the Lancashire lad whose films always proved that whatever the odds, the little people of the world could always come up smiling. We were also suckers for anything a bit sad, and would cry our eyes out over the faithful exploits of Lassie and My Friend Flicka.

One of her prize possessions was an old gramophone complete with a large horn, which she had bought at a jumble sale with a weird and wonderful selection of 78rpm records – everything from Strauss waltzes to Sandy Powell, the radio comic famous for his catchphrase: ‘Can you ’ear me, mother?’ Many a dark winter’s evening was enlivened by those records, and I got to know every one of them by heart. Sometimes Mam would let me take the gramophone into my little bedroom, where I would stick a long white lace curtain over my head and another round my waist and whirl round and round to the strains of The Blue Danube or The Skaters’ Waltz. I was not alone in being an ardent fan of Shirley Temple, but I felt alone in imagining that I could be a famous star like her, if only some Hollywood mogul would come along to the Forest of Dean and discover me.

Mam’s Sunday dinners were scrumptious; I looked forward to them all week, and was never disappointed. It was a pity that her talents were not quite so obvious when it came to slightly more elaborate cooking. I shall never forget her rice puddings, the sort you ate in slices when cold, and her rhubarb pies tended towards the stodgy. Welsh cakes were a bit more successful – but whatever the dish, Dad and I never complained. She tried so hard, and what her cooking lacked in quality she made up for in quantity. There was certainly never a lot left over for the cats and dogs, and as Mam said: ‘What don’t vatten ’ull vill up.’

In his later years, at least, Dad was as interested in what was in his baccy pipe as what was on his plate – not the most healthy state of affairs for a man racked by silicosis after almost a lifetime in the deep mines. It was heart-breaking having to watch him struggle for breath and listen to that terrible cough that plagued him night and day, but when he asked for an ounce of twist, his only real pleasure in his old age, how could Mam refuse? A boiling of Spanish liquorice and linseed, taken hot or cold, would ease his chest awhile. His thick vest would always be oozing goose grease, and I lost count of the bottles of patent medicines he tried and found wanting.

A Mothers’ Union outing from Christchurch, with Mam and Aunts Roseand Lucy in the group.

In early summer I often went with him to gather coltsfoot off the old clay pit mounds around Berry Hill. He would hang them in bunches around our back kitchen until they had dried enough to rub into a rough kind of smoking mixture. This gave off a pungent smell which pervaded every room, and I was always secretly thankful when his stock ran out and it was back to the proper baccy.