Where in the World is the Berlin Wall? E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Berlin Story Verlag GmbH

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A symbol of freedom, of the human strength of will and a relic of the Cold War. Countless pieces of the Berlin Wall were scattered around the globe after the Wall fell in 1989. These pieces of Wall embody the Berliners fight for freedom. More than 240 of these sections - each weighing tonnes - can be found in over 140 countries and on every continent. They have been located for this book. Amongst those who now own sections of the Wall are Japanese businessmen, famous art collectors and all US Presidents from the last century. There are some exciting and strange, but also tragic stories behind the pieces of the Wall. The stories in this book highlight the many ways in which the Wall has been used to commemorate the Berlin Wall and the Cold War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 454

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WHERE IN THE WORLD IS THE BERLIN WALL?

Edited by Anna Kaminskyon behalf ofThe Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship

Project management: Ruth Gleinig

Compiled by Ronny Heidenreich and Tina Schaller

IN MEMORY OF

Dr. Ulrike Guckes

née Gleinig

1978 – 2013

Where in the World is the Berlin Wall?

Published on behalf of

The Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship

Kronenstraße 5

10117 Berlin

www.bundesstiftung-aufarbeitung.de

1st edition – Berlin: Berlin Story Verlag 2014

ISBN 978-3-95723-704-0

All rights reserved.

Editorial deadline: 30th March 2014

© Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, 2014

Berlin Story Verlag GmbH

Unter den Linden 40, 10117 Berlin

Tel.: (030) 20 91 17 80

Fax: (030) 69 20 40 059

E-Mail: [email protected]

Translation: Simon Hodgson

Cover: Norman Bösch

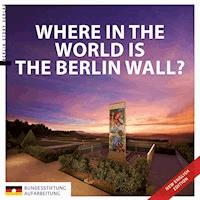

Cover picture:

Simi Valley, California, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum

WWW.BERLINSTORY-VERLAG.DE

TABLE OF CONTENT

PREFACE

Anna Kaminsky

FROM THE BUILDING OF THE BERLIN WALL TO THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE DIVISION

Maria Nooke

“THERE ARE PLENTY OF GOOD REASONS TO ALSO NOT LOSE SIGHT OF THE 13TH AUGUST.”

REMEMBERING THE WALL SINCE 1990

Anna Kaminsky

WHERE IN THE WORLD IS THE BERLIN WALL

Europe

North America

Central America

South America

Africa

Asia

Australia and Oceania

Mars

BETWEEN DISAPPEARANCE AND REMEMBRANCE

REMEMBERING THE BERLIN WALL TODAY

Rainer E. Klemke

THE MESSAGES OF THE WALL SEGMENTS

Leo Schmidt

FROM CONCRETE TO CASH

TURNING THE BERLIN WALL INTO A BUSINESS

Ronny Heidenreich

LIST OF AUTHORS

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Geographic Index

PREFACE

From the 13th August 1961, the Wall – built by the communist rulers in East Berlin – not only divided the German capital into East and West. The Wall was also a symbol of the inhuman regime behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ and of the divided world – the Soviet ruled communist dictatorship in the East block and the democratic states in the western hemisphere.

In the summer of 1989, the communist states were already in a state of ferment and their people had already begun to voice their protests with ever growing courage. Neither those in the East, nor those in the West could have imagined that the Wall would fall anytime soon, nor could they have imagined that the communist dictatorship would be vanquished and the Cold War would come to an end.

Whilst the GDR government continued to talk at great length about the permanency of the Berlin Wall, trade union federation ‘Solidarity’ was celebrating the first legislative elections in Poland. The GDR government continued to open fire on citizens who wanted to choose their own path in life and fled to the West. At the same time, Hungary began to open the ‘Iron Curtain’.

As late as 5th February 1989, East German border troops shot 20 year old Chris Gueffroy as he attempted to get over the Wall and into the West. Hundreds of people were shot at the Berlin Wall and inner-German border as they tried to flee East Germany. The inhuman border regime and the Wall ruined the lives of countless people who lost their friends, family or homes.

The Peaceful Revolutions in almost all countries in the former East Block and the Fall of the Berlin Wall make up some of the most significant events in history. With these revolutions, the people of the GDR and Central and Eastern Europe vanquished the communist dictatorships and brought about the beginning of the end of German and European division.

As a result of the revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Empire collapsed within a few months. As hundreds of thousands of people danced and celebrated on top of the Berlin Wall, the Wall also became a symbol for free will and the triumphant struggle against oppression and dictatorship.

Almost all traces the Wall left on the cityscape had disappeared within a few years. After experiencing freedom, democracy and unity, it seemed there was a strong desire to remove any traces left by this awful past. It was not until 15 years after the Fall of the Wall, when there was almost nothing left to see of the monument that once divided the city, that the Berlin Senate began to work on a memorial concept to remember the Berlin Wall and the division of the city. What was left of the Wall should be preserved and the relationship between the remains told as part of the memorial concept.

Whilst people in Berlin began to dispose of the Wall as quickly as possible, interest in the Wall from around the world was massive. Countless sections of the Wall, which had once surrounded and walled in West Berlin (each weighing tonnes), found new homes all around the world. Today, they can be found on every continent, where they stand as historical memorials, victory trophies, as symbols of freedom or as works of art and commemorate overcoming German division and the struggle for freedom and democracy. 146 sites all over the world, each home to a piece of the Berlin Wall, have been chosen for this book. 241 complete segments of the Berlin Wall and a further 45 smaller pieces, from both the exterior Wall and the so called ‘hinterlandmauer’ – which marked the border in West or East Berlin – are presented in this book. The owners of the pieces of Wall have been asked to tell the story behind ‘their’ pieces of Wall. Some of the stories that have been uncovered are exciting and peculiar, some are tragic. They reflect the multifaceted and complex ways in which the Berlin Wall is remembered. The stories are by artists who wanted to create memorials to freedom, by politicians whose political careers were influenced and shaped by the Berlin Wall. The stories are also by private individuals whose fates were in some way linked with divided Germany. Art museums and collectors display the sections of Wall at their exhibitions due to their bright graffiti. They are often put on display in historical museums and stand as representatives of the confrontation between East and West and the victory for freedom and democracy against oppression and dictatorship. One section of the Wall was blessed by the Pope in the Portuguese city of Fátima and today, pilgrims from all over the world flock to it. There is also a section of the Wall in the gardens in Vatican City and thanks to NASA, the Wall has even left its mark on Mars. The Wall has been the starting point for many moving, artistic and sometimes funny and peculiar stories and works of art.

The remains of the Berlin Wall have been scattered across the globe and serve as witnesses to the Cold War and the confrontation between democratic states and dictatorships. Unattached from the concrete interpretations from where the segments of Wall once stood, they make one thing very clear: people allover the world remember the division of Germany and the joy felt when the Wall fell. The Wall is still seen today as a symbol of the collapse of the totalitarian communist systems.

We would like to sincerely thank all those who have shown support or contributed to this book, be it by supplying photos, researching or anything else. Without your willingness to share your stories and experiences, photos and memories as well as going to the most remote places in search of traces, we would not have been able to show and tell many of the stories included in this book. Many thanks!

Berlin, March 2014

Anna Kaminsky

FROM THE BUILDING OF THE BERLIN WALL TO THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE DIVISION

Maria Nooke

On 13th August 1961 at 1:00am, the lights went out at the Brandenburg Gate and police and members of the East German army moved towards the sector border. Ten minutes later, the GDR announced that measures were being taken which would help to “guard and control”.1

Within a few hours, the GDR government had closed the border to West Berlin with barbed wire. An impermeable border fortification was built over the next days and weeks – the Berlin Wall. Pictures of this formidable border installation were sent around the world. Confused faces and a wall of armed soldiers at the Brandenburg Gate have become engraved on collective memory.

28 years later, on 9th November 1989, the Brandenburg Gate was again the focus of worldwide attention. The Wall had fallen. There were images of people dancing with joy on the concrete Wall in front of the Brandenburg Gate.

The euphoria felt when the division came to an end was not only felt by Berliners, not only by Germans in the East and the West, but by people all over the world.

The Wall had divided Berlin for over 28 years. The beginning and end of the Berlin Wall marked significant landmarks in world history, which history books would later refer to as the ‘Cold War’. The Berlin Wall was a physical construction which showed the inhumanity of the GDR government. A government that became known for shooting its own citizens if they tried to escape. When the Wall fell on 9th November 1989, it became a symbol for the peaceful victory over German division. The fate of the GDR had been sealed with the Fall of the Wall and German reunification was made possible.

The Brandenburg Gate after the Fall of the Wall

© Archiv Bundesstiftung Aufarbeitung / Coll. Uwe Gerig No. 4563

GERMANY UNDER OCCUPATION AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR

The reasons leading to the building of the Berlin Wall go back to the Second World War, which had been instigated and lost by Germany. When it became clear that Hitler was going to lose the War, the Allies began to negotiate plans to split Germany into new territories once Hitler had been defeated. Germany was to be divided into three, later four, zones of occupation and a special status was arranged for Berlin, the capital city. The city was also to be divided into four sectors with an Allied Kommandatura. Former county borders were used to help decide where the sector borders should lie. Hitler’s system of power was to be destroyed once and for all by dividing the country. At the Yalta conference in February 1945, it was decided that an Allied Control Council would be established and should govern Germany. The Allies assumed that there would be no division of power amongst the individual zones, but that they would be governed together.

On 2nd August 1945, the Potsdam Agreement by the Allies aimed to reconstruct Germany, both socially and politically. This meant democratisation of the political system, demilitarisation and denazification, radical changes to the economy and decentralisation in politics, administration and the economy. However, it became clear during the talks at the Potsdam Conference that the powers, once united, would find it difficult to agree how to govern Germany and that such an agreement was no longer possible.

The effects of conflicting interests became clear in the subsequent period, especially when looking at the varying political and economical systems put in place.

In the Soviet occupation zone (SBZ), social economical conditions changed and became the basis for a people’s democracy according to the Soviet model.

A communist one-party dictatorship was quickly put in place and the economy became a planned economy through communisation of property.

In the western occupation zones, in contrast, economical and political structures were put in place which reflected traditional western democracy and a private system of ownership took shape. The relationship between the Allies deteriorated due to these conflicting positions. In March 1948 the Soviets left the Allied Control Council and plans for the Four Powers to govern Germany together failed. The two sides of Germany developed into increasingly independent states.

After the War, the German people reacted to the situation in occupied Germany in their own way, and millions of people flocked over the demarcation line. They were in search of home, family members or simply looking for ways and means to survive. Migration from the Soviet occupied zone to the western zones was, from the beginning, greater than that from the western zones to the East. The majority of the refugees were displaced people from the former eastern territories of Germany which once belonged to Poland. The continued economical and political sovietisation in the East was also a reason for the increasing numbers of people fleeing west. The final break between the Allies was caused by introducing a new currency in the western zones. Aimed at putting a stop to the flourishing black market and to create a stable economy – thereby strengthening economical development in the West – the West Mark was officially introduced on 20th June 1948 in the western zones. A reaction from the Soviet zone was inevitable – otherwise the SBZ economy would have crashed – the old currency flowed where it was still worth something, in particular to East Berlin.

The Soviet military administration in Germany (SMAD) retaliated by introducing the East Mark within its zone on 24th June. The SMAD requested the Mayor of Berlin to make this currency compulsory for the western sectors in Berlin – this was deemed to be inoperative and the D-Mark became the official currency for West Berlin. In Berlin, there were now two currencies in circulation.

At the same time the monetary reform was introduced, the Soviets began the Berlin Blockade. All access points to West Berlin were blocked. The existence of the western side of the city was under threat. Essential supply channels were cut off from one day to the next. There were no means of delivering coal, electricity or food. By depriving West Berlin of such essentials, the Soviets hoped to put the people under pressure and remove Berlin from the power of the western Allies. However, the western Allies did not give up and instead they organised an airlift to provide West Berlin with essential supplies. Planes from the American and English airforces took off and landed every minute, loaded with goods to prevent West Berlin from starvation. This resulted in a change in the relationship between the citizens of West Berlin and the western Allies: they could trust the Allies and the occupiers became friends. The airlift had a lasting effect which was seen again immediately after the Fall of the Wall when the city was once again found itself in an extreme situation.

RESTRICTIONS BETWEEN ZONES AND SECURING DEMOCRACY

The foundation of the two German states in 1949 and the escalation of the Cold War had a grave influence on the safeguarding of a demarcation line between the occupation zones in Berlin.2

At first, the borders between the occupation zones and the sectors within Berlin only served as governing borders. However, in the course of the political developments, they became much more influential and eventually real customs and economical borders.

Crossing the inner-German border was initially possible without significant problems – but officially illegal. By 1946, the Soviets had founded the border police. At the same time, the border between the Soviet and western Zones was closed for three months to curb the huge numbers of people and goods leaving the East. From 1948, so called border violators were increasingly searched for by the Soviet side. They were trying to curb smuggling and the black market, but also to chase down saboteurs and spies.

From 1950, the border police were given the task of surveying the crossing points. In order to better govern the flow of people moving between the borders, the Soviets introduced border passes in 1946. They were valid for 30 days and were issued for urgent family or business trips. During the Berlin Blockade, the Soviets made it compulsory to be issued also with a temporary residence permit alongside the border pass. By doing this, the aim was to reduce the flow of people travelling between the Zones. Crossing the borders illegally was, however, still possible. Many still chose the less dangerous route through Berlin as Berlin was still quite accessible due to its special status.

On 1st April 1948, on orders from the Soviet zone, a police reform was put in place: a ‘ring around Berlin’ was created along a path of 300 km surrounding the entire city (including West Berlin) and controls were carried out. This made it possible to survey the open border as well as was possible at a time when the migration of people from the Soviet zone of occupation was becoming an ever increasing problem.

When the GDR was formed in October 1949, 1.9 million people had already left for the West.

Conflicting interests from the Soviets on one side, and those from the USA, Great Britain and France on the other prevented a peace treaty from being signed. In 1952, the Soviet Union made a step towards solving the problems caused by conflicting political interests and agendas, and the first Stalin Note was sent. Stalin offered the reunification in a neutral unified Germany – free elections should take place under Allied control. By doing this he, wanted to prevent Germany from becoming part of the Western Defence Alliance. The western Allies rejected his offer as they feared it to be a bluff and saw it instead as an attempt to spread the Soviet influence over Germany.

This rejection of terms, alleged activities of sabotage and the constant migration of people prompted the GDR officials, under Soviet influence, to close the border between the GDR and West Germany in May 1952 and gain control of movement between borders.

The border was now a real inner-German border. A five kilometre exclusion zone was set up on the GDR side of the border to secure the 1,378 km long border – an order from the Soviet occupiers. This area could only be entered or traversed with permission. Meetings and events were prohibited from 10:00pm.

A ten-metre-wide control strip was dug up along the border. Deforestation was carried out in green areas along the border. Ramparts, ditches and alarmed trip wires were installed behind the border. Crossing the ten metre long control strip was an arrestable offence. Border police were ordered to shoot those who did not follow their orders. A 500 metre-wide protection strip was closed around the ten-metre stripe in which approximately 110 villages lay. Inhabitants of these villages were subjected to particularly harsh regulations: being outdoors in the 500m area was only permitted during the hours of sunlight and all traffic was forbidden after dark and alterations to land was forbidden without permission. Numerous restaurants and hotels were forced to close down after the protection strip had been constructed. Routes along the Brocken Railway, which linked the Harz mountain range in North Germany, had to be closed as the trains were no longer allowed to travel through western territory.

People living in the restricted area were no longer issued with passes to travel between zones, and people from West Germany were also no longer allowed to travel over the 5km long strip. To put an end to the cries of outrage from the people, a special scheme was put into place which saw the forced resettlement of so called enemies, criminals and ‘suspicious’ people from the protection strip.

‘Operation Vermin’ was the name given to the actions that saw 11,000 residents forcibly moved out of the border area in a matter of days. Violence was used in part to move these people from their homes.3

Not only did these people lose their communities, but also a great deal of their personal possessions. Around 3,000 people avoided forced resettlement by fleeing to the West.

Closing the border also meant closing many transport links. 32 railway lines, three motorways, 31 A-roads, 140 country roads and thousands of other roads were blocked.4

A consequence of this was a zone surrounding the West which had negative implications on the economical situation in areas close to the border and on the quality of life for the people living nearby.

The West German government created incentive programmes which aimed to help minimise the effect the precarious situation having on the people. People on the GDR side of the border were kept quiet with special discounts and benefits. They were treated to pay rises, tax deductions and improved pensions. They were also supplied with better consumer goods.

In Berlin, too, there were similar incisions when the border was closed in 1952: 200 streets were closed. Almost 75% of transport links between West Berlin and the surrounding areas were no longer in use. Control strips were dug up on numerous sites around Potsdam and West Berlin. Vast areas of private land (often belonging to the West) fell victim to securing the border.

Compensatory damages to land owners were few and far between and many land owners received absolutely nothing. As well as the measures being taken along the border, telephone lines and electricity supplies between East and West Berlin were cut off. The GDR wanted an independent infrastructure for East Berlin.

However, the number of people leaving East Berlin did not decrease. Most of the escapees continued to try their luck over the border in Berlin, which remained open. Controversial domestic political situations, like those during collective farming and the forced development of Socialism ahead of the people’s uprising on 17th June 1953, were reasons for many GDR citizens to leave East Germany.

In 1953, the West German government set up a refugee centre in Marienfelde in West Berlin to help manage the number of people entering. At this refugee centre and other similar centres, refugees had to go through an official procedure. Successful refugees could obtain residency permits and be integrated into West German society.5

The western powers chose to suspend compulsory inter-zone passes in November 1953 and stopped issuing temporary permits of residence. Therefore, there were no longer restrictions on travel in the West. In contrast, a law passed by the GDR in 1954 which made fleeing the GDR illegal.6

Fleeing the GDR was now punishable with up to three years imprisonment. The laws were tightened further in 1957 when preparations to flee and attempted escapes were also made punishable.7 Restrictions by the GDR officials on approved travel to the West also followed. Permission to travel to the West depended on one’s age and job. Students, for example, were not permitted to travel to West Germany or any western countries.

THE BERLIN ULTIMATUM AND CRISIS

In autumn 1958, Soviet party leader, Nikita Khrushchev, gave the western Allies an ultimatum and caused the second crisis for Berlin. He ordered the “transformation of Berlin into an autonomous political entity – a free city”, that should be demilitarised and “free from interference from any state including the two German states”.8

If the Allies did not comply with these orders within six months, he would carry out his planned measures within the GDR and grant it its own statehood. Khrushchev wanted to use Berlin’s weak position as a lever for his political aims and cement the recognition of Europe’s situation, achieved during the Second World War. Furthermore, he wanted to prevent nuclear disarmament and reduce the West German military.

His suggestion to make Berlin a “free city”, aimed to get rid of the four-power-status and left the West fearing that the Soviets did actually intend to integrate West Berlin into their zone.

With this solution intending to weaken the West9, Khrushchev also wanted to close the loophole around Berlin and gain control of the refugee problem. The Soviets were no longer striving for reunification. However, the western Allies were not prepared to give up their rights and rejected his suggestions. This advance from the Soviets caused more unrest amongst the people and, in turn, led to a renewed wave of refugees. Many GDR citizens feared that the escape route over Berlin would be lost forever.

On 3rd-4th June 1961, a meeting was held in Wien between the newly elected US President, John F. Kennedy and Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, against this tense backdrop.

Khrushchev pushed for the signing of a peace treaty and threatened once again to enforce this on the GDR if America was not prepared to agree to his suggestions. A separate peace treaty would also be offered to West Germany. Such a treaty would mean the end of the war and nobody would be forced to surrender. This would concern the entire law of occupation as well as access to Berlin including the airlift. Khrushchev threatened that any violation of GDR ruling would be classified as a declaration of war.

On the other hand, Kennedy emphasised that part of the responsibilities resulting from the war would mean that by leaving Berlin, the US would lose credibility in the eyes of the Allies. Therefore, due to his political responsibility, he could not approve this. It was not about Berlin, it was about the whole of western Europe as well as US state security, to which Berlin was of crucial strategical importance. Kennedy wanted to maintain the balance of power in the post-war order as he thought any shift would be detrimental. Both representatives of the major powers left Vienna without reaching agreement. At a speech on 25th June 1961, Kennedy once again named the ‘Three Essentials’ directing the US course of action in West Berlin: 1) the right of western Allies to be present in Berlin, 2) the right to free access to the city, 3) securing the livelihood of West Berlin and its citizens. The ‘Three Essentials’ were proclaimed worldwide in a large-scale campaign. Kennedy formulated them specifically for West Berlin and not the whole of the city, as the special status would have implied. This position signalled to the Soviet Union the need to accept the originally reserved rights for their sector and to agree to the closure of the border in the interest of avoiding military confrontation.10

THE GDR BEFORE THE BUILDING OF THE WALL

At the start of the summer holidays in 1961, the amount of people fleeing the GDR soared. Many people disguised their escape as a holiday. This was a reaction to the foreign policy as well as the dramatic economic climate and the drastic supply problems that continually escalated.11

As part of a propaganda offensive, the GDR government depicted the refugee movement as a specific method of alienation from the West. In order to prevent further escapes, the GDR set up ‘human trafficking committees’. Alleged ‘human traffickers’ were sentenced to harsh sentences in staged trials. By doing this, the government wanted to distract attention from the truth that people were leaving the GDR of their own free will. So called border workers were also targeted. These were people who lived in East Berlin but travelled to work in West Berlin. They were inspected more frequently at the border and some had their passports and ID taken from them so that they were no longer able to go to work in the West. Due to the economic divide between West and East Berlin, the number of border workers rose to 56,000 before the Wall was built.12

Border workers were paid partly in West German currency and the GDR government used this as propaganda to cause jealousy and resentment amongst the people towards the border workers and also as a means to justify the harsh state treatment towards them. Any wages paid in West German currency were subject to a compulsory exchange. Many services could be exchanged in the GDR for West German cash. In early August, the border workers were forced to give up their jobs in the West and register as job-seekers in the GDR.

GDR propaganda aimed to denounce West Berlin as a dangerous trouble spot in the East-West conflict. The GDR’s campaign accused the FRG government of intensive war preparations, aiming to conquer the GDR and parts of Poland.

The increasing measures taken against refugees and border workers, as well as the fierce propaganda campaigns in the GDR, made suspicions in the West all the more great that it would not just be individuals who were victimised by the GDR government. A televised speech by Khrushchev on 7th August 1961 caused many of those watching to fear that a Wall may be built along the Berlin border. People assumed, however, that the measures would be enforced along the ‘ring around Berlin’. Nobody thought that the city would be cordoned off. That was a massive error of judgement, as would soon be proved.

DECISION TO BUILD THE WALL AND PREPARATIONS TO CLOSE THE BORDER

According to claims by the Czech Minister of Defence, which were televised in the West in 1968, Ulbricht had already put forward a suggestion to lay a barbed wire fence through Berlin during a Warsaw Pact meeting in March 1961.13 In light of this, Ulbricht’s words at a press conference in June 1961 make more sense, “nobody has the intention to build a wall” – words which would later be revealed to be lies. The fact that large amounts of building materials including fence posts and barbed wire were being stored in Berlin, further suggested that plans had long been underway to build a wall. However, the decision to build a wall was first finalised in July and the start of August 1961.14

After the Vienna summit and the dramatic supply crisis in the GDR, which in turn lead to increasing levels of people fleeing the GDR, Ulbricht decided upon a propaganda offensive. He made propaganda relating to the Berlin question and the peace treaty. At the same time, Ulbricht urged the Soviets to close the borders immediately. Khrushchev called for his decision (which should be made by 20th July), and insights into the intelligence agencies regarding the military strength of the western powers, American politics and planned defensive measures.15 The Warsaw Pact states would also be involved in the decision. From 3rd-5th August 1961, a conference for party leaders was held in Moscow. The problems surrounding a peace treaty and West Berlin were discussed. Walter Ulbricht was criticised by his counterparts for slow economic growth and high consumer spending in the GDR. Ulbricht underlined his own position that the border to West Berlin was to be held responsible and demanded it to be closed with immediate effect. However, the states of the Warsaw Pact feared economic sanctions of unpredictable proportions in the event of closing the border. Sanctions which would not only have an impact on the GDR.

There were only two possible solutions to the problem: complete control over all access points to the West, including air corridors, or to build a wall. Since complete control of the air corridors was impossible to implement, Ulbricht’s calls for the border to be closed – meanwhile supported by Khrushchev – led to the planned measures being supported.16

A central argument for the decision was the volatile economical situation in the GDR and the increasing numbers of people leaving for the West. When Ulbricht returned from Moscow, the SED politburo began putting the plans, which had been discussed in Moscow, into action. (Which, in agreement with the Soviet side, were technically already being prepared.)

On 10th and 11th of August, the People’s Parliament, the cabinet and the East Berlin Magistrate passed a decree in typical SED wording explicating the closure of the border. Only comrades in the highest political ranks were let in on the plans in order to keep them secret for as long as possible. At the same time logistical preparations were being made and all the stops were pulled out on the propaganda front to prepare citizens for the radical measures.

It was via this propaganda offensive that Ulbricht invoked fears of military action from the West from which the GDR needed to protect itself. But for the GDR government, this was not actually about protecting GDR citizens, it was about preventing them to free access West Berlin. The aim was to stabilise the GDR.

The action was led by Secretary of the SED, Erich Honecker. He coordinated the complex task of closing the border. An operational group was formed at the Department for National Security to carry out the planned action. Whilst Soviet troops in the GDR and adjacent Eastern Bloc countries had only been reinforced between May and July 1961 with several hundred thousands17, cordoning off the border was to be conducted by the GDR border police, riot police and the company brigades. Entities of the National People’s Army had to be on emergency standby to stop potential attacks from the West. A third squadron was formed by Soviet troops at the Ring of Berlin.

The GDR Ministry of State Security was in charge of securing the building of the Wall domestically. The mission operated under the names “Mission Rose” and “Mission Ring” and took place right across GDR territory. The records of intensive supervision of the people of the GDR were to be passed on to the Ministry hourly for the first two days. All mail in corss-border traffic was subjected to controls and telephone lines to western Germany were cut off completely. A state of all-encompassing supervision was to be established.

CLOSING THE BORDER AND THE CONSEQUENCES OF BUILDING THE WALL18

The systematic closing of the 160 km border around West Berlin began on Sunday 13th August at 1:00am. Members of the People’s and Border Police, as well as members of the Combat Groups of the Working Class were deployed along the border. They had 30 minutes to seal off 81 streets. At 1:30am, the forces also entered numerous train stations and rail traffic between the two halves of the city was permanently blocked. The station at Friedrichstraße was the only exception and remained in service as an interchange station for inter-sector traffic. Passenger trains from the West also stopped at this station.

The streets were sealed off in the following three hours. Pavements were pulled up, railway connections split, barriers erected and barbed wire laid. When the city began to wake up at 6:00am, everything had been closed off. Only 12 road links remained open where people could pass between East and West and they were strictly regulated. The Brandenburg Gate was cordoned off in the following days as well as further streets. Only eight crossings remained and strict controls were carried out at such crossings.

Special edition of ‘BZ’ about the construction of the Wall

© Archiv Bundesstiftung Aufarbeitung

On 15th August, two days since the border had been closed, East Germany’s National Defence Special edition of ‘BZ’ about Council decided that the border should continue to be fortified by the military. In the hours of darkness between 17th and 18th August, work began to replace the barbed wire with concrete blocks. The people of Berlin were deployed to seal up their own border – despite Ulbricht’s claim just two months earlier that “No one has any intention of building a wall”. The Wall became more and more insurmountable with each day that passed.

Citizens in both the East and the West looked on, bewildered. They faced the Wall, furious and powerless.

Members of the People’s Police kept citizens at bay with machine guns under their arms. Those who protested were arrested. People had also begun to gather on the west side of the border. West Berlin police had also been deployed along the border to push people away from the Wall and help prevent the situation from escalating. Everyday life in the city had been turned on its head from one day to the next. Tens of thousands of families were torn apart by the Wall, couples split in two, parents kept from their children, friendships destroyed and neighbourhoods ruined. Countless people lost their jobs, their way of life and their prospects. Indescribable human tragedy went on as the world watched. Some people still managed to escape the East where it was possible. Many broke through the barbed wire or jumped from windows onto safety nets held out by the West Berlin fire brigade. In September and October, more then 2000 people were evicted from their homes along or near the border. People at the inner-German border were also forced to resettle as a result of “Operation Consolidation”.

POLITICAL REACTION

The world held its breath. Was the West going to let this happen on the most tense section of the Iron Curtain? Indeed, Willy Brandt was publicly criticising the closing of the border and referred to it on 13th August as “outrageous injustice”, but could do little more than to call the protecting powers.19

The break with the Four-Power-Agreement by the Soviet Union was also a blow to Konrad Adenauer, Chancellor of the FRG and he made sure not lose sight of the goal for reunification.20

However, Adenauer came under fire due to his reservations, especially assuring the Soviet Union that he would take no actions that would harm the relationship between the Federal Republic of Germany and the USSR and which could harm international relations even further. The situation was tense and fears grew that the outbreak of war was imminent. 300,000 citizens of Berlin gathered in front of Rathaus Schöneberg (in the West) on 16th August 1961. They called for serious action to be taken by the western powers and safe guards for West Berlin. The allies had hardly reacted and anything they had done in reaction was only by means of verbal protest. The discontent felt by the people is clear to see in their banners: “70 hours and no action – doesn’t the West know what to do?” or “Paper protests do not stop tanks”.21 These banners illustrated the fear that the West had given up on Berlin.Willy Brandt wrote a letter to the American President in which he wrote “Berlin expects more than words, Berlin expects political action”. He made a speech directed at those in the East, “to all functionaries of the zone regime, all officers and units”, he appealed to them and told them, “don’t be made fools of! Display human behaviour wherever possible and above all do not shoot at your own people!”

On 19th August 1961, in an attempt to try and calm the people of West Berlin and in order to demonstrate that the island city could rely on him, John F. Kennedy sent Vice President, Lyndon B. Johnson, to Berlin. Accompanying him was General Lucius D. Clay, who had masterminded the Berlin Air Lift. One day later, US troops arrive in Berlin to strengthen the troops already stationed there. 1,500 men arrived.

In his letter of reply, Kennedy wrote to Willy Brandt: “As this brutal closure of the border is a clear admission of failure and political weakness, it obviously means a fundamental Soviet decision that could only be undone by war.”22

The western powers did not wish to risk a war and were forced to respect the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence. Germany appeared to be forever divided. The crisis in Berlin, however, was not ended with the building of the Berlin Wall.

When American officials were prevented from crossing the border at Checkpoint Charlie, tanks were put in place at the border crossing. It was not long before Soviet tanks were brought in and the two sides found themselves in a face-off.

The stand-off lasted 16 hours, finally – as agreed upon in secret negotiations – the Russian tanks moved back first, followed by the American tanks.

It became clear to the world that America had a right to be in Berlin, but could not do anything about the division of the city. America’s promise for a safe and free Berlin was strengthened on 26th June 1963 when President Kennedy visited West Berlin. Berliners cheered as he made his famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech.23

ESCAPCE AND ESCAPE AID AFTER THE BUILDING OF THE WALL

On 15th August 1961, 19 year old East German soldier, Conrad Schumann, jumped over the barbed wire into the West. Schumann, from Zschochau, Saxony, had been sent with his police unit to Berlin and was supposed to guard the border. Doubts about the sense of what he was doing at the border made him leap into freedom. Schumann was the first of over 2,500 border soldiers who evaded service on the border and having to shoot their own compatriots by fleeing to the West.24

The first deadly shots to be fired at the border fell 10 days after the Wall was built. On 24th August 1961, Günter Litfin attempted to escape via a small canal.25 Litfin lived and worked in West Berlin and had been visiting his family in the East. He was shocked to find his way back to the West suddenly blocked. He began to look for a way to get back to his home and job. When he was spotted by border troops, he jumped into the water at Humbolthafen, a small harbour in the River Spree, and began swimming towards the West Berlin banks. The border troops tried to prevent his escape attempt with curtain fire and then aimed for his head. He was hit and disappeared under the water. A little while later, he was pulled from the water – dead. Günter Litfin was the first victim to be shot at the border. He was, however, not the last. Despite the deadly threat, many continued with escape attempts until the Wall fell.26

Citizens from West Berlin were still permitted to enter East Berlin in the days immediately after the Wall was built. Many took this opportunity to smuggle friends and relatives back over the border using West Berlin papers and passports. Passes for West Berliners visiting the East were made obligatory on 23rd August.

This rule was made obsolete on 25th August after the Allies and West Berlin Senate refused to set up GDR permit offices. There was no further direct contact between citizens in the East and the West until the first border-pass agreement was made in December 1963. Only those in possession of a West German passport and foreigners could cross the border – or refugees who used forged papers to get over the border. Others escaped to West Berlin via sewage systems – until the sewers were also blocked up with metal bars. Coming up with new and innovative means to escape knew no boundaries.27

Memorial stone for Günter Litfin in Berlin Mitte

© Archiv Bundesstiftung Aufarbeitung

Holes and weak points were constantly searched for. Many disguised themselves as foreigners and escaped to Scandinavia on the interzonal train. Cars were converted, people concealed in cases, diplomats won over to help with escape attempts, paths made over East Europe and hot air balloons built.

The digging of escape tunnels under the border installations was particularly spectacular.28 Underground burrowing led to 70 tunnels being dug out, however, only a quarter of these were used in successful escape attempts. Many of those trying to escape were arrested or shot. For each escape route discovered, measures were taken to increase security and perfect the border installations.

UPGRADING AND PERFECTING THE BORDER INSTALLATIONS29

Until the mid-nineteen sixties, the inner-city Wall was built using concrete blocks and barbed wire. In the areas between West Berlin and the surrounding land, metal fencing was put up in place of the Wall.

As time went on, a border strip was gradually introduced – it was introduced according to locality and the extent to which the GDR could monitor the area. The border strip was complemented by two, sometimes three, rows of barbed wire fencing, antitank barriers, trip wires, dogs on cable-runs and watch towers. In June 1963, a border area (at some points stretching over hundreds of metres) was set up. Residents and visitors to this area were only allowed to pass with special permits.

Work began on the so called “hnterlandmauer” (hinterland wall), which bordered the death strip on the East and made up the actual border line for citizens of the GDR.

Upgrading the Wall followed in the mid-nineteen sixties and was carried out according to detailed plans by the military. After the first and second generations of Wall, followed the third generation. The third generation Wall was made up of slabs of concrete and was 3,4 metres high. “Grenzmauer 75” (border wall 75) followed in the mid-nineteen seventies. It was an L-shaped wall made from steel reinforced concrete and was 3,6 metres high. This type of wall had been tested for its stability and insurmountability and served as the primary border installation facing the West.

The death strip was 15-150 metres wide and was made up of varying security systems to prevent escape. It was built up from East to West until the end of the 80s as follows: not far from the East facing hinterland wall was a signal fence made up of many electrical wires. If it was touched, an alarm went off. At some points, the fence went half a metre into the ground to prevent people from crawling underneath it. After the fence came watch border troop watch posts and towers – they were built within visibility range to each other and were occupied by two soldiers. A so called “Kolonnenweg” then followed, this was a path along which border troop’s vehicles constantly patrolled. It was lined with floodlights which lit up the death strip and a sand path that went right to the Wall itself. This way, visibility was always good and the field of fire always visible. Right in front of the Wall was a ditch, it was slanted and strengthened with concrete making it almost impossible to overcome in a vehicle. Along the top of the Wall itself was a round pipe which prevented people getting any kind of grip with their hands if they attempted to climb over. At certain weaker points along the border, guard dogs were also put on patrol. The dogs were tied to a wire which ran parallel to the signal fence and could move up and down the length of the wire. In 1989, the border around West Berlin was a total of 156,4 km long, 43,7 km of which ran between the two halves of the city and 112 km between West Berlin and Potsdam.

According to a lineup of the border troops, the strip consisted of 63km of developed land, 32km of wood land and 22,65km of open terrain as well as 37km of “water border”. Along the border there were 41,91km of Grenzmauer 75 (Border Wall 75), another 58,95km consisted of the 3rd generation Wall made up of concrete slabs and 68,42km were cordoned off by an expanded metal fence. The light strip was 161km in length and the signal fence comprised of 113,85km. On the death strip, there were 186 watch towers and 31 leading posts for the border troops. Access to West Berlin was possible via 13 street border crossings, 4 rail way crossings and 8 waterway crossings, which were all safeguarded.30

Diagram showing the border fortifications

© Bundesarchiv-Militärachiv, GTÜ AZN 17130 Bl. 205

SHOOT-TO-KILL ORDER AND FATALITIES

The real danger was not the almost insurmountable barrier, nor was it the People’s Police who worked alongside and supported the border troops. It was not the unofficial staff or volunteers who helped the border police. The deadly threat to those trying to flee the GDR was the fact that they were shot. Even if leaders of the GDR government and military continued to deny that there was an official order to kill (even during court proceedings in the 1990s), killing people at the Wall was common practice.31

From a legalistic point of view, the laws, service regulations and the use of fire arms only implied that it was “allowed legally” to kill, but there was no compulsory order to shoot-to-kill. However, the explicit order for border troops to prevent any escape attempts and destroy anyone violating the border led to 136 deaths at the Berlin Wall alone – most of them killed by gunfire. Amongst the victims were 98 would-be escapees, 30 people from the East and the West who had no intention to flee but were nevertheless wounded or killed after being shot and 8 soldiers serving at the border. The majority of the victims were young men aged between 17 and 29. Furthermore, more than 250, mostly elderly people, died whilst crossing official border control points between East and West Berlin.32

View of the death strip between East and West Berlin 1981

© Archiv Bundesstiftung Aufarbeitung / Coll. Michael von Aichberger No. 698

The last person shot trying to escape over the Wall was 21 year old Chris Gueffroy who was shot on 5th February 1989 whilst trying to escape along the Britz district canal.33 He had heard from a friend that the order to shoot had been lifted and by escaping to the West, he hoped to avoid his compulsory service in the National People’s Army. Whilst the four soldiers who broke off the escape attempt were given a cash reward of 150 Marks and military awards for their actions by the border police, Gueffroy’s friend, who also tried to escape and suffered substantial injuries, was sentenced to three years imprisonment. Significant international pressure led Honecker to lift the order to kill on 3rd April 1989. For Chris Gueffroy this order came too late.

HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTIONS AS A SIGN OF THE DÉTENTE POLICY

Despite the deadly threat and many failed escape attempts, 40,101 people managed to flee from the GDR to the West in the 28 years that Germany was divided. 5,075 escaped over the border fortifications in Berlin.34 In order to alleviate the inhumane situation that had come about as result of German division, the government began looking for humanitarian solutions for those who had been affected. The West Berlin Senate negotiated with GDR officials to introduce a travel permit scheme (Passierscheinabkommen) that made it possible for West Germans to visit relatives in the East for the first time since the Wall had been built. 730,000 citizens made use of this between 19th December and 5th January. In total, 1,2 million visits were registered.

In the same year, after holding dificult negotiation talks, the Federal Republic managed to buy the first political prisoners in the GDR out of prison. This is how 33,755 political prisoners were bought out of prison and resettled in the West by the time the GDR had collapsed. The price to buy such a prisoner out of prison was, however, very high.35

New rules to allow pensioners to travel were also agreed upon in 1963. The real breakthrough followed as a result of the new ‘Ostpolitik’ (eastern policy). The GDR wanted to be accepted as an equal partner under international law on the international stage. In order for this to happen, the GDR had to adhere to humanitarian and political norms. In 1972, as a result of the social, political and economical agreements made between West Germany and some of the Eastern Block, new rules were put in place in relation to travel and visits (these were referred to as the Ostverträge in German). It was also agreed at the same time that East Germans would be allowed to visit relatives in the West in exceptional circumstances.

Following the Helsinki Declaration in 1975, scores of GDR citizens called upon the last act of the Helsinki Declaration and demanded the right to choose their place of residence and made applications to emigrate. The wave of people escaping East Germany had been dramatically reduced due to the laying of mines and automatic firing devices along the inner-German border. However, in 1975, there was a wave of people applying to emigrate.36

In 1975 alone, there were over 20,000 applications made by people wishing to leave the GDR and the numbers were increasing. The state security apparatus was purposefully expanded in order to reduce the number of people wishing to leave.

Under domestic pressure in 1984, the GDR government let 21,000 applicants leave the country and started a surge of arrests as a deterrent. But the hope to have solved the problem this way did not turn out to be the case. The number of applications to emigrate soared in light of the successful applicants. Also in 1986 when travelling regulations for GDR citizens were further loosened and visiting relatives was possible to a greater extent, the numbers of applicants rose again. The discontent amongst the population of the GDR had rapidly increased as a result of the tapering economic situation and daily indoctrination.

PEACEFUL REVOLUTION AND THE FALL OF THE WALL37

The domestic political crisis in the GDR had reached its peak in 1989. The economy was in a disastrous state and the people were growing increasingly discontent. The GDR was facing bankruptcy. Opposition groups had been forming since the mid-80s and had formed a network. The opposition tried to create a counter-public against a government that dominated public opinion and thought. They wanted a democratic society. GDR citizens watched the Soviet Union with great interest as Mikhail Gorbachev began a process of reform. His ‘Glasnost’ and ‘Perestroika’ reforms led the way to previously inconceivable discussions about the problems in the Soviet Union and strived to reinforce autonomy in order to solve the serious problems facing the economy.

Although Gorbachev had opened up the basis of his planned economy, his real intention was to improve communism. As far as foreign policy was concerned, he abandoned the Brezhnev Doctrine which had only allowed limited independence of states in the Warsaw Treaty and gave the Soviet Union the right to military intervention if the Socialist system was deemed to be endangered. From now on. Gorbachev seemed to understand that the states in the Eastern Block had the right to independently govern their own affairs.

As a result, round table talks were held in Poland in February 1989 which led to the Socialist state holding its first free and democratic elections in the following April. The Hungarian rapprochement to the West led to the start of the breaking down of the border zone and the first hole in the ‘Iron Curtain’. In summer 1989, thousands of GDR citizens gathered, who wanted to flee to the West over the Hungarian border. The Hungarian government announced the opening of the border on 10th September 1989 and the floods of people began to cross the border.38

Since the GDR had restricted travel to Hungary, the embassies in Prague and Warsaw were occupied. As the situation in the embassies escalated dramatically, citizen’s movements and new parties began to form in the GDR. They came up with their own phrase “We’re staying here” as opposed to “We want to get out of here” – they wanted to reform the country instead of leaving.

Due to the increasing pressure caused by those wishing to flee, the GDR was forced to grant a right of exit to those holding out in the embassies. On 30th